Abstract

BACKGROUND:

A gynecologic cancer diagnosis and subsequent treatment may cause significant morbidity, leading to increased distress levels and poorer quality of life (QOL) for survivors. Clinicians have explored opportunities to integrate comprehensive distress management protocols into clinical settings using existing supportive care resources.

OBJECTIVES:

The aims were to improve multidisciplinary management of distress using a clinical pathway for gynecologic cancer survivors and to improve patient satisfaction with distress management

METHODS:

This study is phase II of a quality improvement initiative to assess distress using the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer and Patient Related Outcome Measures Information Systems QOL tool and to evaluate the use of a clinical pathway to identify and link gynecologic cancer survivors to multidisciplinary supportive care resources. The data were compared to results from phase I of this study with data triangulation that included medical record audits.

FINDINGS:

Thirty-five percent of survivors reported distress scores of 5 or greater. The use of a clinical pathway model for universal distress screening increased referrals to multidisciplinary service teams from 19 to 34, with a 32% increase in social work referrals. Patients appreciated the comprehensive approach the healthcare team used to treat cancer and help improve QOL.

Keywords: distress screening, gynecologic cancer survivors, supportive care services

AGGRESSIVE MULTIMODALITY TREATMENTS FOR GYNECOLOGIC CANCER may lead to costly, long-lasting side effects that negatively affect quality of life (QOL), cause distress, and affect the psychosocial well-being of gynecologic cancer survivors (Rowlands et al., 2013). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network ([NCCN], 2016) defines distress as an unpleasant experience that can affect patients’ cognition, behavior, emotion, social well-being, and spirit, interfering with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its treatment, and associated physical and psychosocial symptoms.

Background

The drive to address the psychosocial issues of cancer survivors initially stemmed from Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs, which emphasized the importance of screening patients for distress as a critical first step to providing high-quality cancer care (Institute of Medicine, 2007). The American College of Surgeons (2015) Commission on Cancer and NCCN (2016) concur that comprehensive cancer centers should develop referral programs to screen and manage distress at pivotal visits.

Distress has overwhelming consequences for cancer survivors. The true incidence of distress in gynecologic cancer survivors is difficult to know because of lack of provider inquiry, perceived negative stigma of distress, shorter clinic visits with providers, and patients’ reluctance to initiate conversations because of cultural or perceived barriers (Vitek, Rosenzweig, & Stollings, 2007). Cancer survivors face challenges with obtaining timely follow-up appointments, managing treatment side effects that limit the ability to work and perform daily activities, gaining access to care, and incurring increased medical care costs that persist throughout the survivorship period (Ekwueme et al., 2014; Urbaneic, Collins, Denson, & Whitford, 2014). About 40%–50% of survivors experience psychosocial distress at some point during their cancer treatment and surveillance (Mitchell, Lord, Slattery, Grainger, & Symonds, 2012). Understanding distress and providing supportive care early in the treatment trajectory will help to improve gynecologic cancer survivors’ psychosocial well-being.

Distress screening instruments should be reliable and patient-friendly and should focus on QOL. The NCCN Distress Thermometer (DT) has been praised for its ease of integration into clinical practice (Juarez, Hurria, Uman, & Ferrell, 2013; Ploos van Amstel et al., 2013). Use of a generic QOL tool with consideration of disease- and/or treatment-related side effects is most valuable. A multidisciplinary management approach is essential for the psychosocial assessment of cancer survivors (Hanssens et al., 2011). Involving all members of the healthcare team, including oncologists, nurses, social workers, nutritionists, mental health providers, physical therapists, and chaplains, will aid in a program’s success.

This project followed the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) theoretical framework (Glasgow, Vogt, & Boles, 1999). Each component of the framework allows for thorough evaluation of the target population(s) and seeks to find which evidence-based interventions have been proven effective and how the program will be implemented in the practice setting. Although the RE-AIM framework is used mostly within the public health and community sectors, its various areas of application makes it easily adaptive to almost any environment and has been effectively used with patients with cancer for disease promotion. This framework uses an integrative and collaborative approach to project planning, a central construct identified in the literature review of distress screening practices.

Adjusting to the new normal following cancer treatment is challenging. The innovation presented in this article is phase II of a quality improvement initiative to pilot a universal distress screening protocol. Prior to pilot implementation, distress screening did not take place within the ambulatory care center. Phase I used focus groups to identify unmet needs and patient satisfaction with distress assessment and management practices. Information learned from that phase helped to inform the intervention tested in phase II. The aims were to improve multidisciplinary management of distress for gynecologic cancer survivors and to improve patient satisfaction with distress management. Provider satisfaction and protocol feasibility were secondary outcomes. Healthcare providers are pressed to provide continued survivorship services with limited resources. Prior to project implementation, social worker support was not available to gynecologic cancer survivors in the ambulatory care setting at the cancer facility. Ensuring that survivors’ physical and psychosocial needs would be met using existing institutional care services was considered.

Methods

The authors conducted a prospective cohort feasibility pilot to evaluate the use of a clinical pathway to assess distress and triage the multidisciplinary care referral process for gynecologic cancer survivors. This study was accorded exemption status by the Johns Hopkins Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB00066327).

Setting and Participants

This innovation pilot was conducted from January to February 2016 at Kelly Gynecologic Oncology Center at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. The clinic providers oversee about 4,500 patient visits each year. Inclusion criteria were gynecologic cancer survivors aged 18 years or older presenting for routine surveillance beginning three months following primary cancer treatment. Exclusion criteria included patients with active disease or receiving concurrent adjuvant treatment. A cancer survivor was defined as a person who has completed primary treatment for a gynecologic malignancy. The staff included 17 multidisciplinary care providers: physicians, nurse practitioners, clinical residents and fellows, social workers, medical assistants, and supportive care staff.

Procedures

Baseline data were obtained from electronic health records (EHRs) using a convenience sample of patients who presented for surveillance clinic visits from October to November 2015. Documentation of distress and the frequency and type of multidisciplinary referrals were noted. The patient satisfaction survey results from phase I were also included in the data analysis for comparison.

One week prior to implementation, the project team leader conducted three 15-minute educational briefing sessions during routine work hours. The purposes of the pilot intervention were to increase awareness of distress, initiate clinical pathway management, institute application of distress screening tools, and create role-specific duties. Same-day educational briefing sessions were provided to rotating residents and fellows during the pilot. The distress screening tools included the NCCN DT and Problem List, which can be found online at http://bit.ly/1SMfIew, and a quality-of-life survey (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

QUALITY-OF-LIFE SURVEY

Gynecologic cancer survivors were prescreened by the research team following review of the clinic schedule. At the beginning of the clinic visit, a list was provided to support staff. Patients in the waiting room were asked to complete the distress screening tools at check-in. Screening results were reviewed by the medical provider and triaged per the clinical pathway. Social workers were notified of patients with distress scores of 8 or greater for same-day contact via telephone or face-to-face meeting based on patient preference. The distress scores and management plan were documented, and distress screening tools were scanned into the EHR.

Instruments

The NCCN DT and National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) tools were used for evaluating distress screening in the innovation group. The NCCN DT is an 11-point scale ranging from 0–10, with 0 indicating no distress and 10 indicating extreme distress. A score of 4 or higher suggests clinically significant distress (NCCN, 2016). Sensitivity and specificity analysis for NCCN DT cutoff of 4 or greater (0.79) and 5 or greater (0.7) when compared to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and Brief Symptom Index for general caseness (the degree to which the accepted diagnostic criteria for a condition are applicable to a patient) and severe psychological distress, respectively (Grassi et al., 2013). In another study, a cutoff of 5 or greater proved 0.85 sensitivity when compared with the HADS (Tuinman, Gazendam-Donofrio, & Hoekstra-Weebers, 2008).

Further review of the literature revealed the following correlated scores for distress: mild (4–5), moderate (6–7), and severe (8 or higher) (Mitchell, Hussain, Grainger, & Symonds, 2011). Given the limited institutional social worker resources and the information from the literature, a clinical pathway was developed for a distress screening management process. If a patient had mild distress (less than 5), the clinician would review sources of distress, provide patients with a list of hospital and community resources, and offer referrals as needed. If the patient had moderate distress, the clinician would perform the duties listed in the mild distress category and order referrals based on problem need. If the patient had severe distress, the clinician would perform actions under mild and moderate categories, as well as offer a same-day consultation with a social worker. Distress scores, associated problems, and plans of care were documented in the EHR for each patient

The PROMIS–General Health (PROMIS-G) is a 10-item instrument with a maximum score of 50 points, which can be scored into separate Global Physical Health (PROMIS-GPH) and Global Mental Health (PROMIS-GMH) components. A raw score in each physical and mental category (maximum of 20 for each component) was converted to a t score for analysis. Higher scores represented healthier populations and improved QOL (PROMIS, 2016).

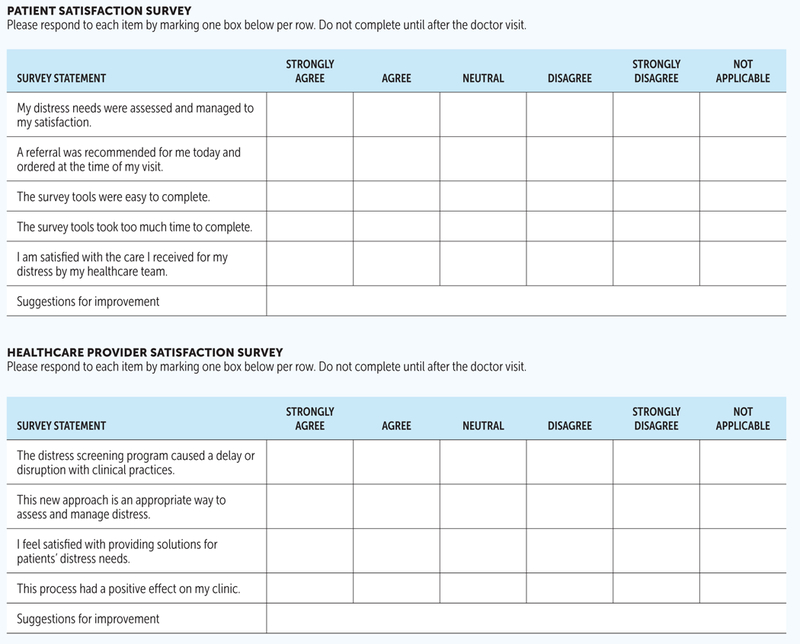

To evaluate satisfaction with distress assessment and management during their visit, patients were asked to complete a five-point Likert-type survey developed by the study team at the end of the visit (see Figure 2). Medical providers completed satisfaction surveys at the conclusion of the pilot program to assess pilot feasibility.

FIGURE 2.

PATIENT AND HEALTHCARE PROVIDER SATISFACTION SURVEYS

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis, frequency, independent t tests, chi-square tests, and multiple logistic regression statistics were used to analyze data obtained from the chart review, pilot participants, and provider satisfaction survey results. Clinical pathway process flow was analyzed by post-clinic chart reviews to determine if the documented distress score correlated with the suggested clinical pathway management plan. Some participants appeared in both retrospective chart audits and in the prospective innovation study. In efforts to preserve an independent sample, those patients were excluded from the prospective data. SPSS®, version 23.0, was used for data analysis.

Findings

Patient Characteristics

The innovation cohort included 65 gynecologic cancer survivors. The historic chart analysis included 73 survivors; 18 patients were removed from the prospective data (see Table 1). The mean age of participants in the chart audit cohort was 55.6 years (SD = 14.4, range = 18–81). The mean age of participants in the pilot phase cohort was 55.9 years (SD = 15.8, range = 20–89). Sixty-five percent of the women were Caucasian, married, and employed with private insurance. The types of cancer diagnoses were similar between groups, with ovarian and endometrial being the most prevalent.

TABLE 1.

DEMOGRAPHIC DATA FROM CHART AUDIT AND PILOT STUDY PARTICIPANTS

| CHART (N = 73) |

PILOT (N = 65) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARACTERISTIC | n | n | p |

| Time since treatment ended (years) | |||

| 1 or less | 26 | 34 | 0.048 |

| 2–5 | 32 | 23 | 0.312 |

| Greater than 5 | 15 | 8 | 0.196 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| African American | 15 | 15 | 0.718 |

| Asian | 2 | 3 | 0.555 |

| Caucasian | 50 | 44 | 0.92 |

| Hispanic | 3 | 2 | 0.748 |

| Indian | 2 | 1 | 0.631 |

| Other | 1 | - | 0.342 |

| Marital status | |||

| Divorced | 5 | 4 | 0.865 |

| Married | 45 | 43 | 0.582 |

| Single | 20 | 16 | 0.711 |

| Widowed | 3 | 2 | 0.748 |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 39 | 34 | 0.896 |

| Not employed | 21 | 12 | 0.155 |

| Retired | 13 | 16 | 0.327 |

| Other | - | 3 | 0.062 |

| Type of insurance | |||

| Medicaid | 4 | 4 | 0.865 |

| Medicare | 19 | 15 | 0.689 |

| Private | 47 | 46 | 0.423 |

| Self-pay | 3 | - | 0.098 |

| Cancer diagnosis | |||

| Cervical | 7 | 9 | 0.435 |

| Choriocarcinoma | 2 | - | 0.18 |

| Endometrial | 33 | 22 | 0.173 |

| Ovarian | 23 | 28 | 0.158 |

| Ovarian and endometrial | 1 | - | 0.342 |

| Vaginal | - | 1 | 0.289 |

| Vulvar | 7 | 5 | 0.696 |

| Treatment receiveda | |||

| Chemotherapy | 1 | - | 0.342 |

| Chemotherapy and radiation therapy |

10 | 6 | 0.412 |

| Surgery | 26 | 30 | 0.207 |

| Surgery and chemotherapy | 23 | 18 | 0.624 |

| Surgery and hormonal therapy | 5 | 2 | 0.312 |

| Surgery and radiation therapy | 5 | 4 | 0.865 |

| Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy |

10 | 6 | 0.412 |

| Surgery, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy |

1 | 4 | 0.133 |

Patients could choose more than one response.

Comparison Between Instruments

The mean distress score was 3.19 (SD = 3.05), with 24 survivors reporting distress scores of 5 or greater. The number of participants with contributing problems were as follows: practical (n = 22), family (n = 10), emotional (n = 36), and physical (n = 50). No participants reported spiritual problems.

The mean PROMIS-GMH raw score was 14.3 (t score = 48.3), and the mean PROMIS-GPH raw score was 14.91 (t score = 47.7). The mean overall PROMIS-G score was 36.05 (SD = 7.72). The relationship between NCCN DT and overall PROMIS-G scores was investigated using Spearman’s product-moment correlation coefficient. There was a strong, negative correlation between the two variables (p < 0.001), with high levels of distress associated with lower levels of overall QOL.

Evaluation of Distress and Referrals

The total number of referrals from the chart audit versus the innovation group was 19 and 34, respectively. Types of referrals included social workers, palliative care, physical therapy, the Kelly Gynecologic Oncology Survivorship Center, and a weight management center. Pearson’s chi-square tests were conducted for each referral type; no social worker referrals were observed in the chart audit group, compared to 21 referrals in the innovation group (p < 0.001). Of the remaining referral types, no significant differences were noted for the remaining referral types (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

FREQUENCY OF MDS REFERRALS FROM CHART AUDIT AND PILOT STUDY

| CHART (N = 73) |

PILOT (N = 65) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| TYPE OF MDS REFERRAL | n | n | p |

| Palliative care | 2 | 1 | 0.629 |

| Physical therapy | 1 | 2 | 0.492 |

| Radiation oncology | 1 | - | 0.344 |

| Social worker | - | 21 | 0.000 |

| Survivorship center | 3 | 4 | 0.585 |

| Other | 12 | 6 | 0.365 |

| Total | 19 | 34 | - |

MDS —multidisciplinary service

Multiple logistic regression analysis (see Table 3) was used to determine if age, marital status, employment status, multiple adjuvant therapies (2 or more), or total number of referrals were associated with distress scores of 5 or greater. Two variables were associated with distress: multiple adjuvant therapies (odds ratio [OR] = 0.312, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.1, 0.979]) and multiple referrals (OR = 0.083, 95% CI [0.008, 0.834]).

TABLE 3.

RESULTS FROM MULTIPLE LOGISTIC REGRESSION ANALYSIS

| CHARACTERISTIC | B | STANDARD ERROR | p | ODDS RATIO | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at encounter | –0.005 | 0.02 | 0.825 | 0.995 | [0.965, 1.036] |

| Employment status | –0.115 | 0.379 | 0.76 | 0.891 | [0.424, 1.871] |

| Marital status | –0.335 | 0.62 | 0.589 | 0.715 | [0.212, 2.412] |

| Multiple adjuvant therapies | –1.164 | 0.583 | 0.046 | 0.312 | [0.1, 0.979] |

| Multiple referrals | –2.492 | 1.179 | 0.035 | 0.083 | [0.008, 0.834] |

CI—confidence interval

Fifty survivors reported mild distress, five reported moderate distress, and nine reported severe distress. Twenty-two referrals were recommended for survivors with mild and moderate distress; five patients declined. Of the 12 referrals recommended for survivors with severe distress, three patients received same-day referrals with social workers. The remaining patients declined same-day consultations because two were already undergoing psychosocial care, two reported that they improved to “mild” distress after reviewing test results with the healthcare provider, and two declined without reason. One patient was not presented the opportunity for a same-day consultation; however, a social worker made contact with that patient within 48 hours. Sixty-seven percent of patients who were recommended a referral at the time of their appointment accepted the services. Overall, the pathway was followed correctly 98% of the time. The NCCN DT score was documented in the EHR 92% of the time.

“Many patients with cancer have multiple comorbidities and side effects from these conditions that contribute to distress.”

Patient and Provider Satisfaction

The pilot satisfaction survey was completed by 38 of 65 survivors, yielding a 58% response rate. Thirty survivors stated that their distress needs were assessed and managed to their satisfaction, with 14 receiving a referral at the time of their visit. The NCCN DT demonstrated ease of use among 34 respondents, with 5 stating that the survey was time-consuming. Twenty-eight respondents noted overall satisfaction with distress management from the healthcare team. A response of strongly agree or agree was deemed satisfactory.

Phase II patient satisfaction survey results were compared with phase I results using independent samples t test. Question items of “my distress needs were assessed and managed to my satisfaction” and “overall satisfaction with the healthcare team” achieved significant results (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.008, respectively). No additional significant differences were noted among the question items. Results are displayed in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

PATIENT SATISFACTION SURVEY RESULTS

Nine of 12 staff members who participated in the innovation pilot completed the provider satisfaction surveys, yielding a 75% response rate. One respondent stated that the screening program caused a delay or disruption with clinic practices. All of the respondents agreed that the new approach was an appropriate way to assess and manage distress. Seven participants felt satisfied with managing patient distress needs, and eight stated the screening program had a positive effect in the clinic. Determining the best timing for screening (e.g., at the beginning versus end of a visit) and how to support patients with high distress unassociated with cancer (e.g., other comorbidities) were listed as suggestions for improvement.

Feasibility of Protocol Implementation

The clinical pathway was specifically developed to assist survivors with same-day referrals for severe distress. Three hours of dedicated social worker time were provided during the pilot period for same-day contact via face-to-face or telephone consultation. Challenges to the availability of social workers during the pilot phase were related to part-time employment status, unanticipated vacation or staff illness, or co-managing other departmental responsibilities. Securing clinical work space for patient interviews and assessments also posed a challenge initially.

Discussion

This study adds to the limited body of literature on distress management and its impact on QOL for gynecologic cancer survivors. The incidence of distress scores of 5 or greater (35%) in this cohort was slightly below the national average of 40%–50% reported in the literature for all cancer types (Mitchell et al., 2012; Vitek et al., 2007); however, it is comparable to that of breast cancer survivors (33%) (Hegel et al., 2008). An inverse relationship was found between distress and QOL, with increased levels of distress resulting in poorer QOL scores, which also correlates with findings from the literature (Chachaj et al., 2010; Foster, Wright, Hill, Hopkinson, & Roffe, 2009; Frumovitz et al., 2005; Hodgkinson, Butow, Fuchs, et al., 2007; Hodgkinson, Butow, Hunt, et al., 2007; Leak, Hu, & King, 2008; Menhert & Koch, 2008; Morrow et al., 2014; Ploos van Amstel et al., 2013; Roland, Rodriguez, Patterson, Trivers, 2013; Taylor et al., 2012). Distress scores of 5 or greater were less likely to be associated with increased referrals and multiple adjuvant treatments. Ellis et al. (2009) found that increased referrals to supportive services were associated with younger age, single marital status, and low socioeconomic standing. The demographic makeup of the innovation cohort in this study likely contributed to the outcome.

Determining the best way to integrate comprehensive psychosocial assessments within cancer care is imperative, particularly when using existing supportive resources. Similar quality improvement studies in the literature showcased success with protocol and practice guideline development (Hammelef et al., 2014; Hammonds, 2012). The study team incorporated multiple management techniques for psychosocial support in the innovation cohort to meet the cultural needs of the institution. The interventions included face-to-face or telephone interviews, a tactic supported by the literature (Matulonis et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2012; Wenzel et al., 2005). This allowed patients to choose consultation preference and increased flexibility for the social workers to optimize their schedules.

The authors noted several clinical findings regarding program implementation that warrant discussion. First, compared to the chart audit group, the innovation cohort had a 32% increase of social worker referrals. This could be, in part, because of the screening pilot itself or because of the collaboration and availability of the social workers to be available for same-day consultations. Second, although gynecologic cancer survivors were overall satisfied with the screening process, the providers reported a few concerns. Two patients were noted to have severe levels of distress at the beginning of the visit. However, after discussing surveillance imaging and laboratory results, their distress levels were reportedly mild. This raised questions regarding the timing of screening (i.e., whether it should be performed at the beginning, middle, or end of the visit). Consideration of repeating screening following a consultation with the physician or having patients complete a referral form, in addition to the screening tool, may help to address this issue. Providers also voiced concerns with how best to support patients with high distress levels unassociated with cancer. Many patients with cancer have multiple comorbidities and side effects from these conditions that contribute to distress. The NCCN DT instructions are generic and do not specifically state to indicate distress level based on cancer and treatment-related side effects, but perhaps this should be included to tailor the consultation and management process.

Limitations

This feasibility pilot was performed at a single cancer center with a small sample size and during a short period of time; therefore, results may not be generalizable to other cancer settings or groups. The authors did not specify the number of months to years from end of treatment for patients, which could affect the outcome and generalizability of results because survivors may have various levels of distress depending on how far out from treatment they are. Third, limited facility space in the ambulatory care setting for social workers to conduct assessments and dedicated clinic time for social worker support may become an issue for continued distress screening. Finally, this study only surveyed patients who completed primary treatment for cancer; multidisciplinary service needs may be higher for newly diagnosed patients with cancer or those on active treatment.

Implications for Nursing

Distress management and psychosocial care are key components to providing quality oncology nursing care. The NCCN (2016), American College of Surgeons (2015) Commission on Cancer, Institute of Medicine (2007), and Oncology Nursing Society (Eaton & Tipton, 2009) have recommendations for including distress management in clinical practice. This pilot was a nurse-developed initiative that can be translated into clinical settings to improve supportive services for cancer survivors, even in limited-resource settings. Feasibility pilots can be helpful in assessing program development. Additional work is required before complete sustainable implementation can occur across all clinics and pivotal medical visits. Incorporating screening tools into the EHR, linking the patients’ office visit, and multidisciplinary service referral recommendations should be considered best practice. In addition, long-term process and formal evaluation of protocol implementation should be ongoing to determine whether distress levels are decreasing over time for gynecologic cancer survivors.

Conclusion

The clinical pathway developed successfully triaged distress needs for gynecologic cancer survivors. Patients and providers praised the screening program and valued its importance in providing comprehensive cancer care. Having access to multidisciplinary services for supportive care, particularly social workers, can be challenging. Further research is needed to determine the most appropriate time to implement distress screening and the repeat distress screening intervals along the gynecologic cancer trajectory. Focusing on cancer-related distress can help improve patient and program outcomes.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE.

-

▪

Translate this nurse-developed initiative into clinical settings to improve supportive services for cancer survivors.

-

▪

Incorporate screening tools into the electronic health record to link patients’ office visits and multidisciplinary service referral recommendations.

-

▪

Implement the protocol continuously to determine whether distress levels are decreasing over time for gynecologic cancer survivors.

Footnotes

The authors take full responsibility for this content and did not receive honoraria or disclose any relevant financial relationships. The article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is objective and free from bias.

REFERENCES

- American College of Surgeons. (2016). Cancer program standards: Ensuring patient-centered care Retrieved from https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/2016%20coc%20standards%20manual_interactive%20pdf.ashx

- Chachaj A, Malyszczak K, Pyszel K, Lukas J, Tarkowski R, Pudelko M, . . . & Szuba A (2010). Physical and psychological impairments of women with upper limb lymphedema following breast cancer treatment. Psycho-Oncology, 19, 299–305. 10.1002/pon.1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LH, & Tipton JM (2009). Putting Evidence Into Practice: Improving oncology patient outcomes Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Society. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J, Lin J, Walsh A, Lo C, Shepherd FA, Moore M, . . . Rodin G (2009). Predictors of referral for specialized psychosocial oncology care in patients with metastatic cancer: The contributions of age, distress, and marital status. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27, 699–705. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR, Guy GP Jr. Banegas MP, de Moor JS, Li C, . . . Virgo KS (2014). Medical costs and productivity losses of cancer survivors—United States, 2008–2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63, 505–510. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster C, Wright D, Hill H, Hopkinson J, & Roffe L (2009). Psychosocial implications of living five years or more following a cancer diagnosis: A systematic review of the research evidence. European Journal of Cancer Care, 18, 223–247. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.01001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frumovitz M, Sun C, Schover L, Munsell M, Jhingran A, Wharton J, . . . Bodurka D (2005). Quality of life and sexual functioning in cervical cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23, 7428–7436. 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, & Boles SM (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi L, Johansen C, Annunziata MA, Capovilla E, Costantini A, Gritti P, . . . Bellani M (2013). Screening for distress in cancer patients: A multicenter, nationwide study in Italy. Cancer, 119, 1714–1721. 10.1002/cncr.27902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammelef KJ, Friese CR, Breslin TM, Riba M, & Schneider SM (2014). Implementing distress management guidelines in ambulatory oncology: A quality improvement project. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18(Suppl. 3), 31–16. 10.1188/14.CJON.S1.31-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammonds LS (2012). Implementing a distress screening instrument in a university breast cancer clinic: A quality improvement project. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, 491–494. 10.1188/12.CJON.491-494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssens S, Luyten R, Watthy C, Fontaine C, Decoster L, Baillon C, . . . De Grève J (2011). Evaluation of a comprehensive rehabilitation program for post-treatment patients with cancer [Online exclusive]. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38, E418–E424. 10.1188/11.ONF.E418-E424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegel MT, Collins ED, Kearing S, Gillock KL Moore CP, & Ahles TA (2008). Sensitivity and specificity of the Distress Thermometer for depression in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 17, 556–560. 10.1002/pon.1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Fuchs A, Hunt GE, Stenlake A, Hobbs KM, . . . Wain G (2007). Long-term survival from gynecologic cancer: psychosocial outcomes, supportive care needs and positive outcomes. Gynecologic Oncology, 104, 381–389. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, Pendlebury S, Hobbs KM, & Wain G (2007). Breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 2–10 years after diagnosis. Supportive Care in Cancer, 5, 515–523. 10.1007/s00520-006-0170-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2007). Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juarez G, Hurria A, Uman G, & Ferrell B (2013). Impact of a bilingual education intervention on the quality of life of Latina breast cancer survivors [Online exclusive]. Oncology Nursing Forum, 40, E50–E60. 10.1188/13.ONF.E50-E60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leak A, Hu J, & King C (2008). Symptom distress, spirituality, and quality of life in African American breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nursing, 31, E15–E21. 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305681.06143.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matulonis UA, Kornblith HL, Bryan J, Gibson C, Wells C, Lee J, . . . Penson R (2008). Long-term adjustment of early-stage ovarian cancer survivors. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, 18, 1183–1193. 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01167.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehnert A, & Koch U (2008). Psychological comorbidity and health-related quality of life and its association with awareness, utilization, and need for psychosocial support in a cancer register-based sample of long-term breast cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 64, 383–391. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Hussain N, Grainger L, & Symonds P (2011). Identification of patient-reported distress by clinical nurse specialists in routine oncology practice: A multicentre UK study. Psycho-Oncology, 20, 1076–1083. 10.1002/pon.1815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Lord K, Slattery J, Grainger L, & Symonds P (2012). How feasible is implementation of distress screening by cancer clinicians in routine clinical care? Cancer, 118, 6260–6269. 10.1002/cncr.27648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow PK, Broxson AC, Munsell MF, Basen-Enquist K, Rosenblum CK, Schover LR,. . . Hortobagyi GN (2014). Effect of age and race on quality of life in young breast cancer survivors. Clinical Breast Cancer, 14, E21–E31. 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2016). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Distress management [v.2.2016]. Retrieved from https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/distress.pdf

- Patient-Reported Outcomes Measures Information System. (2016). PROMIS®. Retrieved from http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis#5

- Ploos van Amstel FK, van den Berg SW, van Laarhoven HW, Gielissen MF, Prins JB,Ottevanger PB (2013). Distress screening remains important during follow-up after primary breast cancer treatment. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21, 2107–2115. 10.1007/s00520-013-1764-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland KB, Rodriguez JL, Patterson JR, & Trivers KF (2013). A literature review of the social and psychological needs of ovarian cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 2408–2418. 10.1002/pon.3322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands IJ, Lee C, Janda M, Nagle CM, Obermair A, & Webb PM (2013). Predicting positive and negative impacts of cancer among long-term endometrial cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 1963–1971. 10.1002/pon.3236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor T, Huntley E, Sween J, Makambi K, Mellman T, Williams C, . . . Frederick W (2012). An exploratory analysis of fear of recurrence among African-American breast cancer survivors. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 19, 280–287. 10.1007/s12529-011-9183-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuinman MA, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, & Hoeskstra-Weebers JE (2008). Screening and referral for psychosocial distress in oncologic practice. Cancer, 113, 870–878. 10.1002/cncr.23622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbaniec OA, Collins K, Denson LA, & Whitford HS (2014). Gynecologic cancer survivors: Assessment of psychosocial distress and unmet supportive care needs. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 29, 534–551. 10.1080/07347332.2011.599829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitek L, Rosenzweig MQ, & Stollings S (2007). Distress in patients with cancer: Definition, assessment, and suggested interventions. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 11, 413–418. 10.1188/07.CJON.413-418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel L, DeAlba I, Habbal R, Klushman BC, Fairclough D, Krebs LU, . . . Aziz N (2005). Quality of life in long-term cervical cancer survivors. Gynecologic Oncology, 97, 310–317. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]