Abstract

Background

To determine a new pralidoxime (PAM) treatment guideline based on the severity of acute organophosphate intoxication patients, APACHE II score, and dynamic changes in serum butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) activity.

Methods

This is a randomization trial. All patients received supportive care measurements and atropinization. Each enrolled patient was treated with 2 gm PAM intravenously as the loading dose. The control group was treated according to the WHO's recommended PAM regimen, and the experimental group was treated according to their APACHE II scores and dynamic changes in BuChE activity. If a patient's APACHE II score was ≧26 or there was no elevation in BuChE activity at the 12th hour when compared to the 6th, doses of 1 g/h PAM (i.e., doubled WHO's recommended PAM regimen) were given. The levels of the serum BuChE and red blood cells acetylcholinesterase and the serum PAM levels were also measured.

Results

Forty-six organophosphate poisoning patients were enrolled in this study. There were 24 patients in the control group and 22 patients in the experimental group. The hazard ratio of death in the control group to that of the experimental group was 111.51 (95% CI: 1.17–1.613.45; p = 0.04). The RBC acetylcholinesterase level was elevated in the experimental group but was not in the control group. The experimental group did not exhibit a higher PAM blood level than did the control group.

Conclusion

The use of PAM can be guided by patient severity. Thus, may help to improve the outcomes of organophosphate poisoning patients.

Keywords: Organophosphate, Poisoning severity, PAM dose

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

The use of pralidoxime in the treatment of organophosphate poisoning is still under investigations. Studies have shown that a higher mortality was observed among severe intoxicated patients with the convention treatments. Therefore, it is required to treat the patients according to their organophosphate intoxicated severity.

What this study adds to the field

This study found that the severity index, such as APACHE score, can be a guide for designing pralidoxime dose. Better patient outcomes were observed when treated according to their organophosphate intoxicated severity. The findings suggest an innovative tailored-made treatment protocol to organophosphate intoxicated patients in the future emergency medicine practice.

Acute pesticide poisoning is a major global health problem across the world [1], [2]. In Taiwan, organophosphate intoxication accounted for 26.97% of all of the pesticide poisonings [3]. Acute respiratory failure and even death are quite common outcomes of acute organophosphate (OP) poisoning [4]. PAM has been used as an antidote for the treatment of acute OP poisoning patients; however, its use remains controversial [5], [6], [7]. The WHO's recommended PAM regimen (in adults, 30 mg/kg bolus, followed by a continuous infusion of 8 mg/kg/h to rapidly achieve and maintain a concentration of PAM above 4 mg/L) is based on animal studies [8]; moreover, the type of OP pesticide and the poisoning dosage influence the effects of treatment with PAM [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Thus, the clinical presentations and severity of OP poisoning may be complicated, and the effectiveness of PAM treatment requires re-examination.

According to the available literature, the acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II (APACHE II) score and serial cholinesterase changes are two OP poisoning severity assessment tools [15], [16], [17]. Higher mortality rates were observed among those with higher APACHE II scores in previous studies [15], [16]. Increasing patient mortality rates was associated with the absence of elevating butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) activity within 48 h of poisoning although they were treated with the similar PAM dosages. [17] Therefore, it seems reasonable that these effects may be linked to PAM dose prescriptions.

Based on the hypothesis that PAM dosages should be determined according to the severity of acute OP poisoning, this study aimed to examine the effectiveness of tailored treatment for acute organophosphate poisoning patients. Therefore, this study assessed a new PAM dosage regimen that is based on the severity of acute OP poising (i.e., APACHE II score) and dynamic changes in serum BuChE activity. Serum PAM concentrations, the changes of serum BuChE and red blood cell AChE (RBC AChE) activities were also measured to investigate how these factors were related to the prognosis and toxicokinetics of acute organophosphate poisoning patients.

Methods

Study design and patient population

This study received the approval of our local ethics committee (97-2306A3), and written informed consent was obtained from each patient or their closest relatives. This study was a randomized open-label controlled study. Randomization was performed by flipping a coin by research nurse at the admission of patients if included in the study. The study period was from August 2010 to July 2013. We stop the trial at the end of the study period. Patients who visited the emergency department of the Linkou Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital or the China Medical University Hospital were enrolled. The Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital is a 3000-bed medical center, and the China Medical University Hospital is a medical center that is located in the central area of Taiwan. Patients aged >16 years presenting with evidence of OP poisoning were included in this study. The identification of OP poisoning was based on exposure history, clinical features, and decreased plasma BuChE activity(less than 3000 U/L). The study excluded patients with any of the following conditions: (1) an uncertain history of exposure or an uncertain time of poisoning, (2) carbamate poisoning, (3) coingestion with other fatal intoxicants or fatal injuries, (4) intoxication time more than 24 h, and (5) pregnancy.

Treatment protocol

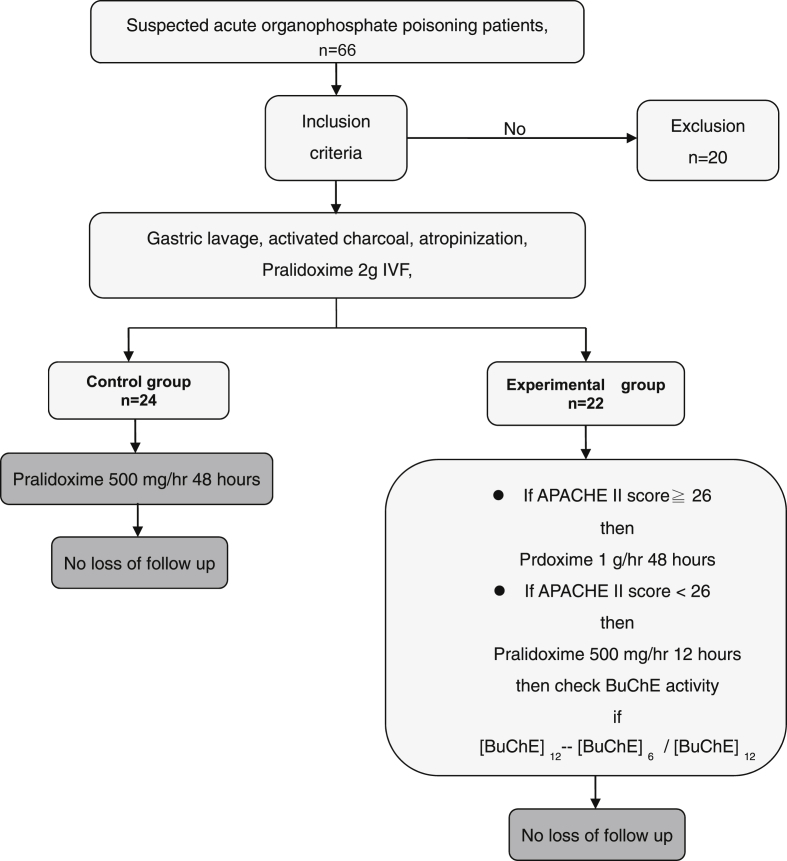

The patients were randomly divided into a control group and an experimental group. Each enrolled patient was treated with gastric lavage, activated charcoal administration when no contraindications were present and airway protection when needed. Other supportive treatments, such as endotracheal intubation for acute respiratory patients, were also performed when needed. Appropriate atropine doses were administered according to patients' clinical presentations, i.e., 1 mg atropine intravenously every 10 min until “dry lung”. Each enrolled patient was treated with 2 gm PAM intravenously as the loading dose. The control group was treated according to the WHO's recommended PAM regimen, i.e., 500 mg/h. The experimental group was treated according to their APACHE II scores (if that score was ≧26) and dynamic changes in BuChE activity [Fig. 1]. If a patient's APACHE II score was ≧26 or there was no elevation in BuChE activity at the 12th hour when compared to the 6th BuChE activity ([BuChE]12 − [BuChE]6/[BuChE]12 <5%), doses of 1 g/h PAM (i.e., doubled WHO's recommended PAM regimen) were given [16], [17]. PAM was discontinued when the patient was free of OP poisoning symptoms and signs or the patient experienced treatment failure.

Fig. 1.

Study synopsis.

Outcome measurement

The pre-defined outcomes were in hospital mortality as the main outcome, intubation rate and intermediate syndrome were the secondary outcomes.

Data acquisition

This study examined the following data: demographic factors (age, sex, and body weight), history of intoxication (specific OP agents, times and routes of exposure, intentional or accidental exposure), clinical manifestations, emergency department (ED) triage vital signs, the total amount of PAM used within 48 h of poisoning, the total amount of atropine used, intermediate syndrome and the hospitalization day. The laboratory data required for APACHE II scores (i.e., white blood cell count, hematocrit, platelet count, serum blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, sodium and potassium concentrations, and arterial blood gas) were used to determine severity of each patient's poisoning. Serum BuChE or RBC AChE activities were measured at arrival and every 6 h until 24 h and at 48 h after poisoning. Intubation and mortality were our measurement end points. BuChE activities were measured with Kodak Ektachem Clinical Chemistry Slides, which are dry, multilayered, analytical elements. The normal range is 3000–9300 U/L. The coefficient of variation for this test was lower than 3.5%, when the measured samples were greater than 1160 U/L. Thus, an increase in BuChE activity was defined as an elevation of the follow-up BuChE activity of 5%. Side effects of PAM, such as arrhythmias, hypertension, and blurred vision, were also recorded [18], [19], [20]. RBC AChE activities were measured according to the method described by Padilla et al. [21].

Statistical methods

Continuous variables are expressed as the median (Q1, Q2), and categorical variables are displayed as frequencies and percentages (%). For univariate analysis between groups, we used Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables, and the χ2 test for categorical variables. Variables found to be statistically significant in the univariate analysis were selected as candidates for the subsequent multivariable Cox regression analysis. Multi-variable adjusted hazard ratios were used to express the strength of the influence of each factor on mortality. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Participant characteristics, poisoning severities, drug doses and outcomes

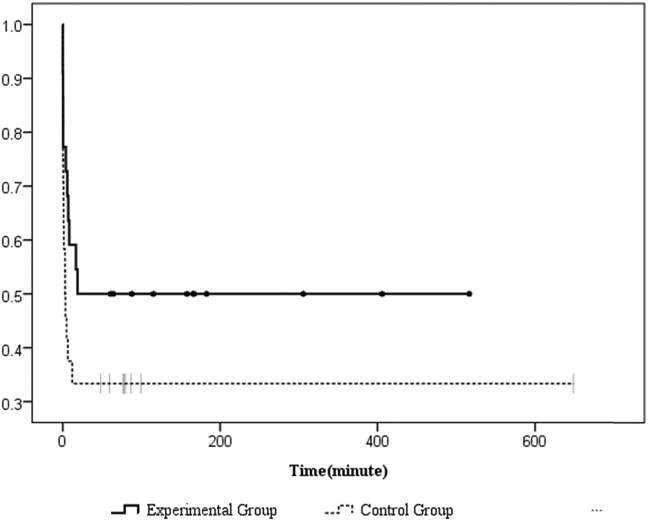

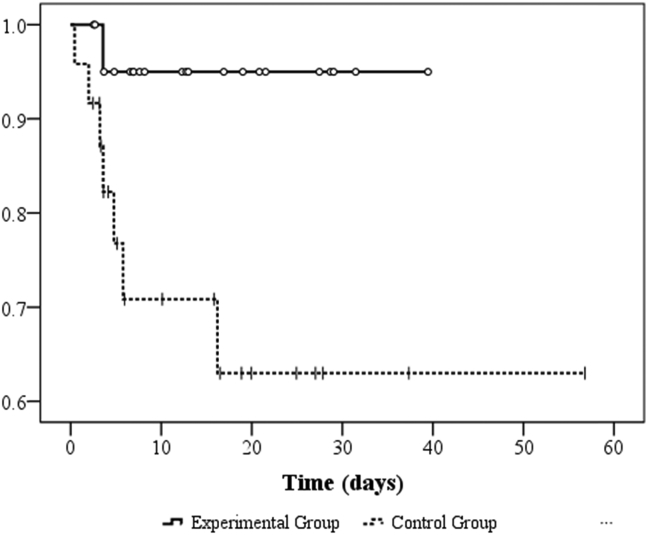

A total of 66 patients were assessed on ED admission, and 46 patients met our criteria for eligibility, provided consent, and were randomized into the trial. Twenty patients were excluded due to the following reasons: carbamate poisoning (n = 6), pregnancy (n = 1), co-ingestion of other intoxicants (n = 5), normal cholinesterase level (n = 2), and no inform consent (n = 6).Twenty-four patients were eligible in the control group, and 22 patients were included in the experimental group [Fig. 1]. The demographic characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. There were no differences in basic characteristics between the two study groups. The median (Q1, Q3) age was 56.0 (46.0, 71.0) and 62.0 (50.0, 75.5) years old (p = 0.34) in the experimental group and control group, respectively. Both groups were male predominantly (n = 32, 71.7%). The types of causative organophosphates were diethyl (n = 28, 60.9%), dimethyl (n = 12, 26.1%) and unknown (n = 6, 13%). Most of the enrolled patients were suicidal (n = 41, 91.1%), and oral ingestion (n = 43, 93.5%) was the major route of poisoning. Table 2 illustrates the comparisons of the initial and serial changes in BuChE, RBC AChE activities, poisoning severities, and outcomes. There was no different poisoning severity existed between these two groups because of there were no differences in the initial and follow up BuChE, RBC AChE activities (differences between the 6th hour BuChE or RBC AChE the 12th hour) and different poisoning severities scores (APACHE II, amylase and QTc interval). Also, there were no difference in atropine doses, total amount of PAM doses and duration of PAM usage between these two groups, however, the experiment group had higher PAM doses before 48 h after treatment (31.55 ± 10.20 gm vs. 22.27 ± 5.87 gm, p = 0.001). In assessment of the outcomes, as shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2, the rate of intubations and intermediate syndrome had no difference between the two study groups. The overall mortality in this trial was 8/46 (17.39%). The mortality was higher among the patients who received the WHO's recommended PAM regimen (control group: 7/24 [29.17%]) than in the experimental group (1/22 [4.55%]; p = 0.048 and Fig. 3). The multivariate-adjusted hazard ratio of death of the control group was 111.15 (95% CI = 1.71–10613.45; p = 0.04) that of the experimental group. Moreover, we found two other indicators, respiratory rate and APACHE II score, that were significantly associated with mortality. The multivariate-adjusted hazard ratios for respiratory rate and APACHE II scores ≧26 were 0.42 (95% CI = 0.23–0.76; p = 0.004) and 7.82 (95% CI = 1.01–60.33; p = 0.05), respectively [Table 3].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the enrolled patients.

| Experiment group (n = 22) |

Control group (n = 24) |

p valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Q1, Q3) or n (%) | Median (Q1, Q3) or n (%) | |||

| Age | 56.0 (46.0, 71.0) | 62.0 (50.0, 75.5) | 0.34 | |

| Gender | Male | 16 (72.72) | 17 (70.83) | 0.89 |

| Female | 6 (27.27) | 7 (29.17) | ||

| Body weight | 66.0 (55.8, 75.0) | 60.0 (54.0, 65.0) | 0.21 | |

| Types of OP | Diethyl | 11 (50.00) | 17 (70.83) | 0.28 |

| Dimethyl | 8 (36.36) | 4 (16.67) | ||

| Unknown | 3 (13.63) | 3 (12.50) | ||

| Manner of poisoning | Intentional | 18 (85.71) | 23 (95.83) | 0.30 |

| Accidental | 1 (4.76) | 1 (4.17) | ||

| Unknown | 2 (9.52) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Route of exposure | Oral | 20 (90.91) | 23 (95.83) | 0.21 |

| Inhalation | 0 (0.00) | 1 (4.17) | ||

| Dermal | 2 (9.09) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| ED vital signs | ||||

| BT (°C) | 36.1 (35.9, 36.5) | 36.0 (35.5, 36.5) | 0.74 | |

| HR (/min) | 95.0 (88.0, 112.0) | 86.5 (74.0, 107.5) | 0.25 | |

| RR (/min) | 20.0 (18.0, 20.0) | 19.0 (17.5, 20.0) | 0.52 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 151.0 (131.0, 164.0) | 138.0 (124.0, 170.0) | 0.55 | |

| DBP (mmHg) | 87.0 (84.0, 94.0) | 86.0 (75.0, 98.0) | 0.76 | |

| Laboratory variables | ||||

| WBC (1000/μl) | 9.6 (7.0, 15.9) | 17.5 (12.1, 19.7) | 0.03 | |

| Hct (%) | 42.0 (36.2, 45.7) | 42.3 (38.8, 45.8) | 0.49 | |

| Plt (1000/μl) | 233.0 (162.0, 277.0) | 228.5 (175.5, 269.5) | 0.74 | |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 16.8 (15.0, 19.0) | 15.7 (12.4, 28.4) | 0.94 | |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.84, 1.21) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.5) | 0.06 | |

| Na (mEq/L) | 139.0 (138.0, 141.0) | 141.0 (136.5, 142.5) | 0.37 | |

| K (mEq/L) | 3.4 (3.1, 3.7) | 3.4 (3.0, 3.8) | 0.81 | |

| PH | 7.4 (7.3, 7.4) | 7.4 (7.3, 7.4) | 0.46 | |

| HCO3 (mm/L) | 21.1 (18.8, 23.6) | 19.7 (16.9, 23.6) | 0.46 | |

| PO2 (mmHg) | 81.1 (65.0, 157.5) | 87.0 (60.5, 153.9) | 0.80 | |

| PCO2 (mmHg) | 38.1 (31.8, 42.0) | 36.2 (27.4, 40.0) | 0.45 | |

Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for continuous variables, and χ2 test was used for categorical variables.

Table 2.

Serum BuChE, RBC AChE activities, poisoning severities, and outcomes.

| Experimental group (n = 22) |

Control group (n = 24) |

p valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Q1, Q3) or n (%) | Median (Q1, Q3) or n (%) | |||

| AChE activity | ||||

| BuChE (0 h) | 2087.5 (1167, 3723) | 1504 (1033, 2253) | 0.15 | |

| RBC AChE (0 h) | 3569 (1576, 6594) | 2611 (1424, 4246.5) | 0.27 | |

| △BuChE12–6b | 148 (−194, 960) | 32.5 (-831, 397) | 0.11 | |

| △BuChE12–6 ≧5% | 9 (47.40) | 10 (52.60) | 0.56 | |

| △RBC AChE12–6b | 144 (−721, 616) | −193.5 (-1069, 332) | 0.32 | |

| Poisoning severity | ||||

| APACHE II | ≧26 | 2 (9.09) | 4 (16.67) | 0.67 |

| <26 | 20 (90.91) | 20 (83.33) | ||

| Amylase (U/L) | 93 (47.5, 162) | 107 (45, 193) | 0.73 | |

| EKG_QTc (ms) | 458 (442, 473) | 473 (435, 516) | 0.34 | |

| Drugs dosage | ||||

| Total amount of Atropine (mg) | 5.5 (0, 33) | 2 (1, 15) | 0.92 | |

| Total amount of PAM before 48 h (gm) | 24 (24, 42) | 24 (24, 24) | <0.001 | |

| Total amount of PAM after 48 h (gm) | 20 (5, 77) | 12 (0, 32) | 0.28 | |

| Total amount of PAM (gm) | 52 (36, 101) | 36 (24, 56) | 0.09 | |

| Duration of PAM (h) | 72 (48, 240) | 55 (48, 120) | 0.45 | |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Intubationc | No | 11 (50.00) | 7 (29.17) | |

| Yes | 11 (50.00) | 17 (70.83) | 0.25 | |

| Mortalityc | Survive | 21 (95.45) | 17 (70.83) | |

| Death | 1 (4.55) | 7 (29.17) | 0.05 | |

| Intermediate syndrome | No | 14 (63.64) | 19 (79.17) | |

| Yes | 8 (36.36) | 5 (20.83) | 0.40 | |

Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for continuous variables, and χ2 test was used for categorical variables.

△BuChE12–6 and △RBC AChE12–6: the difference between the 6th hour BuChE and RBC AChE at the 12th hour.

Hazard ratio (95% CI) of intubation occurrence and mortality was 7.23 (0.89, 58.88) and 1.97 (0.85, 4.59), respectively, performed by Cox regression model.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier overall intubation by minutes of organophosphate poisoning patients, p = 0.0998.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier overall survival by days of organophosphate poisoning patients, p = 0.0271.

Table 3.

Cox regression model for mortality among acute organophosphate poisoning patients.

| Variables | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group (control vs. experiment) | 111.51 | (1.171, 10,613.45) | 0.04 |

| Age (each increment in 1 year) | 1.02 | (0.95, 1.10) | 0.58 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 3.48 | (0.50, 24.24) | 0.21 |

| Body temperature (each increment in 1 °C) | 0.52 | (0.15, 1.84) | 0.31 |

| Respiratory rate (each increment in 1/min) | 0.42 | (0.23, 0.76) | 0.004 |

| APACHE II ≧26 (vs. <26) | 7.82 | (1.01, 60.33) | 0.05 |

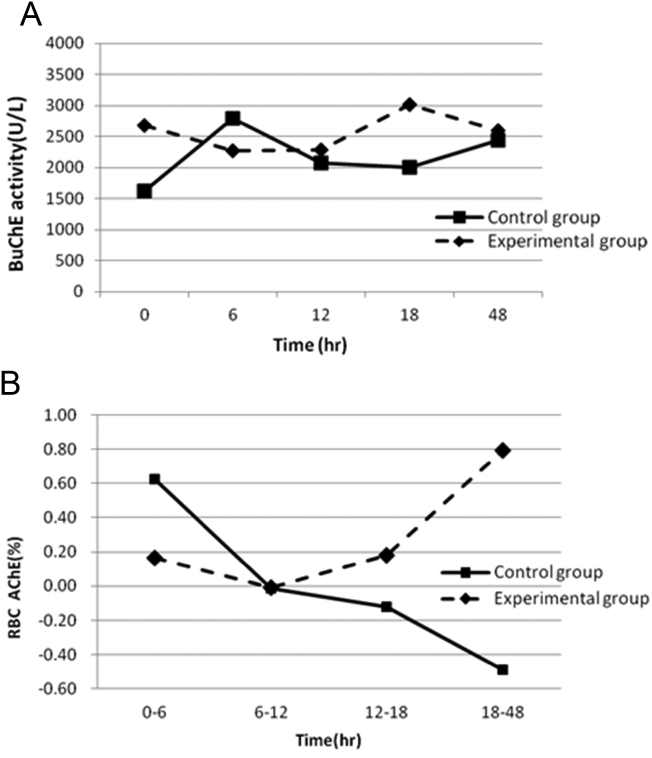

Acetylcholinesterase activity within 48 h

The changes in BuChE were not associated with time and were not significantly different between the two study groups within the first 48 h after PAM treatment [Fig. 4A]. However, the patterns of changes in the RBC AChE activities were significantly different between the two study groups [Fig. 4B]. An increase in RBC AChE was observed in the experimental group (slope = 0.207), and a decrease was observed in the control group (slope = −0.34).

Fig. 4.

A. BuChE activities over 48 h between the two study groups. B. Changes in RBC cholinesterase observed between the two study groups. 0–6 = [AChE]12 − [AChE]6/[AChE]12, etc.

Serum PAM concentration and its adverse effect

All patients had serum PAM concentrations exceeding 4 mg/L. There was no statistically significant difference in serum PAM concentrations between the groups at any time points [Table 4]. There was no liver injury found in both study groups. Patients in the experiment group had higher systolic blood pressure in 24 h (142.77 ± 40.71/82.27 ± 23.10 vs. 148.45 ± 28.83/87.14 ± 17.68, p = 0.59) but return to normal blood pressure within 48 h (128.73 ± 23.82/71.73 ± 15.99 vs. 126.90 ± 23.34/74.70 ± 16.36, p = 0.80).

Table 4.

Serum PAM concentrations at the different time points.

| PAM (mg/L) | Experimental group |

Control group |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Q1, Q3) | Median (Q1, Q3) | ||

| 0 h (loading) | 2.78 (0.28, 17.78) | 0.35 (0.00, 11.91) | 0.49 |

| 6th hour | 17.5 (5.51, 29.93) | 23.59 (11.63, 56.48) | 0.20 |

| 12th hour | 25.58 (15.18, 32.19) | 24.32 (14.59, 39.75) | 0.97 |

| 18th hour | 50.14 (21.43, 72.61) | 26.93 (16.20, 37.66) | 0.49 |

| 48th hour | 22.42 (11.90, 67.15) | 27.68 (20.41, 74.7) | 0.53 |

Discussion

Gunnell and Eddleston estimated that approximately 300,000 deaths/year occur due to intentional pesticide poisoning in developing countries [2]. The mortality of the experimental group of this study was found to be 4.5% that was much lower than that of the control group. Consequently, the results of this study challenge the value of PAM in the treatment of organophosphate intoxication, which remains a matter of controversy. In a meta-analysis conducted by Buckley et al., the authors stated that the current evidence is insufficient to indicate whether oximes are harmful or beneficial. These authors also concluded that their findings did not support the WHO-recommended regimen. Nevertheless, these authors suggested that flexible dosing strategies based on patient subgroup analyses might be required [7]. In this study, we demonstrated that the treatment of organophosphate poisoning should be based on the severity of the each patient poisoning. We also found that the WHO's recommended PAM blood level is not ideal for the management of organophosphate poisoning. As proposed by Eyer and other authors, the guideline for the administration of 4 mg/L PAM should be further revised and discussed [22], [23]. Pawar et al. suggested that a high-dose regimen of PAM that consists of a constant infusion of 1 g/h for 48 h following a 2 g loading dose reduces the morbidity and mortality of moderately severe cases of acute organophosphorus pesticide poisoning [24]. The results of our study corroborate this finding and suggest that higher PAM doses should be used for patients with more severe poisoning. In contrast to Pawar's suggestion, a dynamic treatment protocol based on the severity of the patient's organophosphate intoxication would be more flexible.

One of the main factors limiting the success of PAM therapy is the continuing presence of high concentrations of organophosphates in the plasma [25]. Previous studies have shown that the rapid re-inhibition of reactivated AChE during the first day following organophosphate intoxication is often observed, particularly for those organophosphate with biological half-lives longer than one day [11], [26]. Therefore, we suggest that PAM should be administered by continuous infusion following an initial bolus dose to counteract the effects of the continuing presence of organophosphates. Furthermore, in an in vitro model, Rios et al. demonstrated that the recovery of AChE activity is PAM dose-dependent. These authors therefore suggested that the maintenance of higher plasma concentrations is the primary goal of organophosphate intoxication treatment [26]. In their study, the reactivation capacity of PAM clearly decreased after the administration of PAM. A 23% reduction in efficacy occurred after 6 h, and no protection was observed 24 h after PAM administration. This in vivo observation provides a foundation for our study findings. The increase in BuChE activity between the 6th and 12th hours that was observed in our study revealed the adequate protective effects of PAM treatment. Additionally, BuChE is mainly synthesized in the liver at a rate of approximately 5% per day [27]. Thus; an increase of more than 5% in the early stage of treatment can be regarded as a reasonable treatment target. Although many organophosphates have half-lives that are longer than one day in humans, the dose of PAM that we administered can last for at least 48 h, and the supplementary treatment doses can sufficiently cover the toxicokinetics of the organophosphates. This reasoning may help to explain the observation that, at comparable intubation rates, the experimental group had a much lower mortality rate than did the control group. In the early phase of OP poisoning, the reactivation of AChE is slow; thus, the toxic effects remain strong and cause respiratory failure that results in the requirement of intubation even when PAM is administered. However, this toxic effect may be abolished with adequate and sustainable PAM administration just as our study showed. The challenge for PAM therapy is to maintain AChE levels. Our treatment regimen (which resulted in an increase in BuChE activity between the 6th and 12th hours) can maintain a sufficient level of AChE in the active state and thereby retard the AChE aging rate.

There was no difference in the plasma PAM concentrations between the experimental and control groups. A mechanism that may potentially explain this finding is that the PAM was consumed by the organophosphates and thus reached an equilibrium in the circulation pool. However, small group size in our study may be the other possible explanation.

RBC AChE and serum BuChE are used as biomarkers of organophosphates [28]. Thiermann et al. reported that RBC AChE activity appears to be a suitable surrogate parameter for synaptic AChE during the first few days of intoxication. A strongly correlation exists between decreases in RBC AChE activity and impairment of neuromuscular transmission. However, increasing BuChE activity is observed during the later stages of organophosphate poisoning [29]. We observed in increase in RBC AChE activity in the experimental group during the early phase of the patients’ intoxication, but BuChE activity did not exhibit such a change. Our findings are similar to those of a report by Thiermann et al. The RBC AChE is suitable for therapeutic monitoring of oxime treatment in cases of organophosphate poisoning because this measure is an easily accessible proxy for synaptic AChE. However, the measurement of RBC AChE is not currently a routine practice; rather the determination of BuChE activity is routinely performed. Additionally, organophosphate-inhibited BuChE reactivating potency was found to be remarkably lower than organophosphate-inhibited RBC AChE [30]. Therefore, better outcomes can be anticipated if the PAM treatment regimen can reactivate BuChE in the early phase of treatment. Thus, our treatment guidelines that increase BuChE activity between the 6th and 12th hours after PAM administration seem to be suitable for the treatment of OP poisoning patients.

Limitations

We demonstrated that the RBC AChE activities tended to increase in the experimental group; nevertheless, this result should be applied cautiously in the future due to the small sample size of this study and the fact that observations were made in only two medical centers. However, we have calculated the post hoc power based on ln(111.51), alpha = 0.05, r [2] of group with other covariates = 0.122, and SD of group = 3.388 and found the statistical power of this study was 0.96. The sample size is sufficiently to draw conclusion of this study. In addition, the samples collected from two different medical settings may cause variability derived from different sources but the effect is nondifferential. We have compared the major characteristics of study samples from the two medical settings. Although there were differences in age (median 65 vs. 52, p = 0.01) and gender (male, 21 vs. 12, p = 0.04) between the two hospitals, however, the APACHE II, the major characteristics (severity index), of the study samples (median 9 vs. 11, p = 0.24) and mortality rate (4/21 vs. 4/17, p = 0.54) from the two hospitals were not statistically different [Appendix Table A]. The exposure doses were not accurately measured in the emergency departments. A measurement bias due to the use of recall questionnaires is likely existed in this study. The patients' outcomes may have been affected by pre-existing underlying diseases. In this study, we adjusted for major confounders in the regression model; however, uncontrollable factors may contribute to the wide confidence interval of the outcomes.

Conclusions

The use of PAM could be guided by APACHE II scores and the reactivation rates of BuChE. We suggest a patient-tailored treatment protocol with PAM doses based on the patient's severity instead of WHO recommendation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by research grants from Ministry of Science and Technology (NSC-98-2314-B-182A-062-MY3, NSC-101-2410-H-182-015, and NSC-102-2410-H-182-010-MY2) of Taiwan, BMRPB10, CMRPD (360011-360013, 370031-370033, 390041-390043, 1B0331), and EMRPD1D0911 from Chang Gung Medical Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

Appendix.

Table A.

The comparison of basic characteristics and clinical features of poisoning patients from different hospital sources.

| Linkou Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital (n = 25) |

China Medical University Hospital (n = 21) |

p valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Q1, Q3) or n (%) | Median (Q1, Q3) or n (%) | |||

| Age | 65 (57, 77) | 52 (45, 68) | 0.0115 | |

| Gender | Male | 21 (84) | 12 (57.14) | 0.0426 |

| Female | 4 (16) | 9 (42.86) | ||

| Body weight | 62 (57, 66) | 61 (53, 70) | 0.4187 | |

| APACHE II | 9 (6, 17) | 11 (8, 23) | 0.2415 | |

| APACHE II | ≧26 | 3 (12) | 3 (14.29) | 0.5784 |

| <26 | 22 (88) | 18 (85.71) | ||

| Mortality | Survive | 21 (84) | 17 (80.95) | 0.5438 |

| Death | 4 (16) | 4 (19.05) | ||

Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for continuous variables, and χ2 test/Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables.

References

- 1.Buckley N.A., Karalliedde L., Dawson A., Senanayake N., Eddleston M. Where is the evidence for treatments used in pesticide poisoning? Is clinical toxicology fiddling while the developing world burns? J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2004;42:113–116. doi: 10.1081/clt-120028756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunnell D., Eddleston M. Suicide by intentional ingestion of pesticides: a continuing tragedy in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:902–909. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang C.C., Wu J.F., Ong H.C., Hung S.C., Kuo Y.P., Sa C.H. Taiwan National Poison Center: epidemiologic data 1985–1993. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1996;34:651–663. doi: 10.3109/15563659609013825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin C.L., Yang C.T., Pan K.Y., Huang C.C. Most common intoxication in nephrology ward organophosphate poisoning. Ren Fail. 2004;26:349–354. doi: 10.1081/jdi-120039816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peter J.V., Moran J.L., Graham P. Oxime therapy and outcomes in human organophosphate poisoning: an evaluation using meta-analytic techniques. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:502–510. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000198325.46538.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahimi R., Nikfar S., Abdollahi M. Increased morbidity and mortality in acute human organophosphate-poisoned patients treated by oximes: a meta-analysis of clinical trials. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2006;25:157–162. doi: 10.1191/0960327106ht602oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckley N., Eddleston M., Szinicz L. Oximes for acute organophosphate pesticide poisoning. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sundwall A. Minimum concentrations of N-methylpyridinium-2-aldoxime methane sulphonate (P2S) which reverse neuromuscular block. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;8:413–417. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willems J.L., De Bisschop H.C., Verstraete A.G., Declerck C., Christiaens Y., Vanscheeuwyck P. Cholinesterase reactivation in organophosphorus poisoned patients depends on the plasma concentrations of the oxime pralidoxime methylsulphate and of the organophosphate. Arch Toxicol. 1993;67:79–84. doi: 10.1007/BF01973675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eddleston M., Szinicz L., Eyer P., Buckley N. Oximes in acute organophosphorus pesticide poisoning: a systematic review of clinical trials. QJM. 2002;95:275–283. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/95.5.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Worek F., Bäcker M., Thiermann H., Szinicz L., Mast U., Klimmek R. Reappraisal of indications and limitations of oxime therapy in organophosphate poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1997;16:466–472. doi: 10.1177/096032719701600808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thiermann H., Mast U., Klimmek R., Eyer P., Hibler A., Pfab R. Cholinesterase status, pharmacokinetics and laboratory findings during obidoxime therapy in organophosphate poisoned patients. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1997;16:473–480. doi: 10.1177/096032719701600809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eddleston M., Eyer P., Worek F., Mohamed F., Senarathna L., von Meyer L. Differences between organophosphorus insecticides in human self-poisoning: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005;366:1452–1459. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67598-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson Martin K., Jacobsen Dag, Meredith Tim J., Eyer Peter, Heath Andrew J., Ligtenstein David A. Evaluation of antidotes for poisoning by organophosphorus pesticides. Emerg Med. 2000;12:22–37. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilgin T.E., Camdeviren H., Yapici D., Doruk N., Altunkan A.A., Altunkan Z. The comparison of the efficacy of scoring systems in organophosphate poisoning. Toxicol Ind Health. 2005;21:141–146. doi: 10.1191/0748233705th222oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee P., Tai D.Y. Clinical features of patients with acute organophosphate poisoning requiring intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:694–699. doi: 10.1007/s001340100895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen H.Y., Wang W.W.J., Chaou C.H., Lin C.C. Prognostic value of serial serum cholinesterase activities in organophosphate poisoned patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:1034–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xue S.Z., Ding X.J., Ding Y. Clinical observation and comparison of the effectiveness of several oxime cholinesterase reactivators. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1985;11(Suppl. 4):46–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott R.J. Repeated asystole following in organophosphate self-poisoning. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1986;14:458–460. doi: 10.1177/0310057X8601400424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finkelstein Y., Kushnir A., Raikhlin-Eisenkraft B., Taitelman U. Antidotal therapy of severe acute organophosphate poisoning: a multihospital study. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1989;11:593–596. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(89)90044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padilla S., Lassiter T.L., Hunter D. Biochemical measurement of cholinesterase activity. Methods Mol Med. 1999;22:237–245. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-612-X:237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eyer P. The role of oximes in the management of organophosphorus pesticide poisoning. Toxicol Rev. 2003;22:165–190. doi: 10.2165/00139709-200322030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eddleston M., Eyer P., Worek F., Juszczak E., Alder N., Mohamed F. Pralidoxime in acute organophosphorus insecticide poisoning – a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pawar K.S., Bhoite R.R., Pillay C.P., Chavan S.C., Malshikare D.S., Garad S.G. Continuous pralidoxime infusion versus repeated bolus injection to treat organophosphorus pesticide poisoning: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:2136–2141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69862-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marrs T.C., Vale J.A. Elsevier Academic Press; United States of America: 2006. Toxicology of organophosphate & carbamate compounds. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rios J.C., Repetto G., Galleguillos I., Jos A., Del Peso A., Repetto M. High concentrations of pralidoxime are needed for the adequate reactivation of human erythrocyte acetylcholinesterase inhibited by dimethoate in vitro. Toxicol In Vitro. 2005;19:893–897. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lotti M. Clinical toxicology of anticholinesterase agents in humans. In: Krieger R.I., editor. Handbook of pesticide toxicology. 2nd ed. Academic Press; San Diego, San Francisco, New York, Boston, London, Sydney, Tokyo: 2001. pp. 1043–1085. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thiermann H., Kehe K., Steinritz D., Mikler J., Hill I., Zilker T. Red blood cell acetylcholinesterase and plasma butyrylcholinesterase status: important indicators for the treatment of patients poisoned by organophosphorus compounds. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 2007;58:359–366. doi: 10.2478/v10004-007-0030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thiermann H., Zilker T., Eyer F., Felgenhauer N., Eyer P., Worek F. Monitoring of neuromuscular transmission in organophosphate pesticide-poisoned patients. Toxicol Lett. 2009;191:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aurbek N., Thiermann H., Eyer F., Eyer P., Worek F. Suitability of human butyrylcholinesterase as therapeutic marker and pseudo catalytic scavenger in organophosphate poisoning: a kinetic analysis. Toxicology. 2009;259:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]