Abstract

Introduction/Purpose

Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) is used as surrogate for arterial blood oxygen saturation. We studied the degree of discrepancy between SpO2 and arterial oxygen (SaO2) and identified parameters that may explain this difference.

Methods

We included patients who underwent cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) at Cleveland Clinic. Pulse oximeters with forehead probes measured SpO2 and arterial blood gas (ABG) samples provided the SaO2 both at rest and peak exercise.

Results

We included 751 patients, 54 ± 16 years old with 53 % of female gender. Bland-Altman analysis revealed a bias of 3.8% with limits of agreement of 0.3 to 7.9% between SpO2 and SaO2 at rest. A total of 174 (23%) patients had SpO2 >= 5% of SaO2, and these individuals were older, current smokers with lower FEV1 and higher PaCO2 and carboxyhemoglobin. At peak exercise (n=631), 75 (12%) SpO2 values were lower than the SaO2 determinations reflecting difficulties in the SpO2 measurement in some patients. The bias between SpO2 and SaO2 was 2.6% with limits of agreement between −2.9 to 8.1%. Values of SpO2 >= 5% of SaO2 (n=78, 12%) were associated with the significant resting variables plus lower heart rate, oxygen consumption and oxygen pulse. In multivariate analyses, carboxyhemoglobin remained significantly associated with the difference between SpO2 and SaO2 both at rest and peak exercise.

Conclusion

In the present study, pulse oximetry commonly underestimated the SaO2. Increased carboxyhemoglobin levels are independently associated with the difference between SpO2 and SaO2, a finding particularly relevant in smokers.

Keywords: pulse oximetry, arterial blood gas, cardiopulmonary exercise test, forehead probe, arterial oxygenation

Introduction

Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) is commonly measured by pulse oximetry, which provides an indirect measurement of arterial oxygenation (SaO2) based on the differential absorption of light by oxygenated and deoxygenated blood during pulsatile blood flow (1). Pulse oximetry offers a non-invasive and rapid determination of SaO2, particularly when the SaO2 is above 75% (2). Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis provides a direct measurement of the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) and SaO2 among other important parameters that are used to assess ventilation and acid base status. However, ABG analysis requires more time and expense as well as an arterial puncture (3). Thus, SpO2 is routinely used as surrogate for SaO2.

Precision and accuracy of SpO2 readings can be affected by technical problems inherent to the measuring device or inadequate interpretation of the data (4). Some sources of error can be modified (i.e. improper probe placement, motion artifact, nail polish, and stray light) while others cannot (i.e., presence of carboxyhemoglobin, methemoglobin, and skin pigmentation). In cases of poor perfusion, the accuracy of the reading can be optimized by changing the probe to a different location (e.g. finger, ear lobe or forehead), applying heat or a vasodilator cream, placing the hand below the level of the heart or trying a different sensor or pulse oximeter (5,6).

A good agreement between SpO2 and the reference method of ABG analysis has been reported by some authors (7), while others reported an over- or underestimation of the SaO2 (8,9,10). Some studies have pointed out that SpO2 may not always be a reliable method to predict SaO2 (11, 12). High venous pressure states can falsely lower SpO2 values (3,13). Furthermore, decreased accuracy of SpO2 has been described in hypoxemic (8), hemodynamically compromised (9,10), and critically ill (14) patients, in whom an accurate and reliable monitoring is of major importance. Increases in carboxyhemoglobin and on certain occasions methemoglobin can lead to falsely normal or high SpO2 readings, despite a low SaO2 (13). The source of error caused by these two dyshemoglobins can be mitigated by using co-oximetry, which requires an ABG.

Most studies investigating agreement between SpO2 and SaO2 have concentrated on critically ill inpatient populations (3,14), and studies in healthier, outpatient cohorts both at rest and during exercise are lacking. The purpose of our study is to examine the degree of discrepancy between SpO2 and SaO2 both at rest and at maximum exercise and identify parameters that may explain this difference. We hypothesize that the discrepancy between SpO2 and SaO2 increases at maximal exercise and that several factors (particularly carboxyhemoglobin) can explain this difference. To test our hypothesis we retrospectively examined a cohort of patients undergoing cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) at our institution, compared SpO2 with SaO2 both at baseline and at peak exercise during CPET, and tested whether variables collected during CPET can explain the differences between SpO2 and SaO2.

Methods

Study Population

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Cleveland Clinic (IRB # 15-1288). Data from 751 patients referred for CPET at the Respiratory Institute of the Cleveland Clinic, from January 2010 to January 2015, were retrospectively analyzed. Informed consent was waived.

Pulse Oximetry and Arterial Oxygenation Determinations

Our CPET protocol included the use of pulse oximeters (Nonin Avant 4000 system, Nonin, Plymouth, MI, USA) with forehead probes to measure SpO2 both at baseline and during exercise. We routinely placed two pulse oximetry probes on the forehead to test accuracy and only recorded the most reliable determination based on the quality of the SpO2 waveform. Forehead oximetry probes were held in place by an elastic band. Respiratory therapists recorded the SpO2 measurement only when the waveform had a dicrotic notch and was synchronized with the heart rate observed in the electrocardiographic monitoring (15). SpO2 at the time of ABG acquisition was recorded both at rest and peak exercise to avoid temporal variations. Measurements at rest were done in the sitting position after the patient relaxed for at least 10 minutes.

As part of our CPET protocol, SaO2 levels were obtained from ABG samples taken from individual punctures of the radial artery (usually the left one) while patients sat on the bicycle. We did not place an arterial catheter. ABG determinations were performed with co-oximetry using the ABL800 FLEX Blood Gas Analyzer (Radiometer, Brønshøj, Denmark). ABG determinations were reported at 37 degree Celsius without correction by the core body temperature. Both SpO2 and SaO2 determinations were taken at rest (before exercise) and at maximum exercise (during the last 1-2 minute, just before stopping). Reasons for not been able to obtain an ABG at maximum exercise include: more than two unsuccessful attempts, transition into the recovery phase, and gasometric findings indicative of venous blood. In every patient, we recorded the amount of oxygen supplementation administered at the time of the measurements. If the patient required any degree of oxygen supplementation, either at rest or during activities, the CPET (including baseline and exercise determinations) was done with a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 30% using a bag reservoir.

Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing (CPET) Protocol

CPET was ordered by pulmonary physicians based on established indications and done on an electrically braked cycle ergometer following recommendations by the American Thoracic Society and American College of Chest Physicians (16). Electrodes were placed on the skin to be able to obtain a 12-lead electrocardiogram. Blood pressure (BP) was recorded using a cuff placed on the arm opposite to the ABG site. An appropriate face mask (7450 SeriesV2 Mask, Hans Rudolph, Shawnee, KS, USA) size was selected and a good seal was verified. Measurements were obtained with the MedGraphics Ultima system (MGC Diagnostics, Saint Paul, MN, USA) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. We used different maximal incremental exercise testing protocols based on the evaluation of each patient and with the intention of adjusting the exercise duration to approximately 8-12 minutes. Tests were terminated when the patient reached exhaustion (defined as 10/10 on the Borg scale or the inability to maintain pedal speed) or developed pronounced dizziness, leg, knee, chest or back pain (16).

For our study we recorded the following CPET variables: work rate, oxygen uptake (VO2), carbon dioxide output (VCO2), respiratory exchange ratio, anaerobic threshold, tidal volume, respiratory rate, minute ventilation (VE), VE/VCO2, VE/VO2, breathing reserve, end-tidal PCO2, heart rate, heart rate reserve, blood pressure, oxygen pulse, exercise duration and reasons for stopping the test. We also recorded SpO2 and SaO2 as well as other ABG results (partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2), alveolar–arterial difference for oxygen pressure, PaCO2, pH, bicarbonate, lactate, hemoglobin and carboxyhemoglobin), maximum voluntary ventilation measured at baseline, and forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and FEV1/FVC (17) both at baseline and immediately after exercise.

Other variables

We collected data on age, gender, height, weight, smoking status, type of CPET protocol (5 to 30 Watts per minute), and reasons for the test. Reasons for ordering CPET were clustered in four groups including a) unexplained dyspnea, b) pre-operative work-up for cardiovascular or lung surgeries, c) diagnose or evaluate treatment response in exercise induced asthma, and d) others. In addition, we reviewed the patient’s medications, time and contents of the last meal.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean ± SD, median (interquartile range (IQR) or n (%)) were used to summarize demographic and clinically relevant variables. Continuous variables were compared with t-test. Categorical variables were tested using chi-square or Fisher exact test, when appropriate. Univariate linear regression was used to examine whether certain variables of interest eloquent were associated with the difference between SpO2 and SaO2 both at rest and peak exertion. Multivariate analysis was subsequently performed to examine the association between variables that achieved a p value < 0.10 in the univariate analysis. Variables in the models were tested for multicollinearity using variance inflation factors (VIF) and removing variables with a value larger than 4. Bland-Altman analysis was used to display the degree of bias and limits of agreement between SpO2 and SaO2 both at rest and peak exertion, using SaO2 as the gold standard in the x axis. We compared the patient characteristics at rest and during exercise between subjects that showed a difference between SpO2 and SaO2 < 5% or >= 5%. This prespecified but arbitrary cut-off was chosen to reflect an eloquent difference between measurements. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value less than 0.05. All analyses were performed using R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (version 3.3.0).

Results

Patient Demographics

The mean age of the cohort (n=751) was 54.1 ± 16.1 years. A total of 355 (47%) patients were male. The majority of the tests were ordered for unexplained dyspnea (n=558 [74.3%]). Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the patients.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Variable | Baseline determinations mean ± SD, n (%) |

|---|---|

| n | 751 |

| Age (years) | 54 ± 16 |

| Male gender | 355 (47.3) |

| Height (cm) | 172.0 ± 6.2 |

| Weight (kg) | 84.2 ± 21.6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.0 ± 7.0 |

| Smoking Status* | |

| Current Smoker | 68 (9.1%) |

| Ex-Smoker | 307 (41.0) |

| Never Smoker | 374 (49.9) |

| Reason for CPET Testingˆ | |

| Unexplained Dyspnea | 558 (74.3) |

| Pre-Operative Workup | 180 (24.0) |

| Exercise-Induced Asthma | 3 (0.4) |

| Other | 9 (1.2) |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CPET = cardiopulmonary exercise testing; SD = standard deviation.

Smoking status is missing in 2 patients,

reason for CPET testing is missing in 1 patient.

Oximetry at baseline

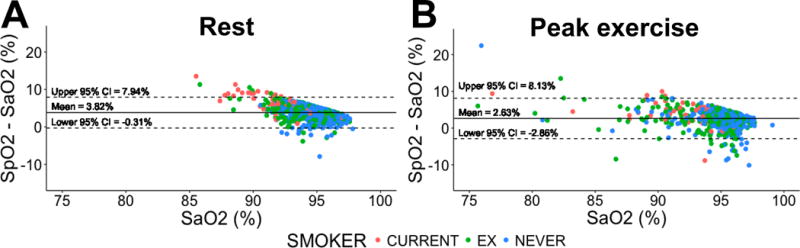

Results of the ABG analysis, spirometry and CPET at baseline are shown in Table 2. The baseline SpO2 was 98.2 ± 1.8 %. The test was done on room air in 735 (97.9%) patients and on gas with 30% FiO2 in the rest (n=16, 2.1%). The SpO2 in individuals on room air and FiO2 30% was 98.2 ± 1.8 and 98.3 ± 1.3%, respectively. Meanwhile, the SaO2 was 94.4 ± 1.7 and 95.2± 1.3% for those breathing room air and FiO2 of 30%, respectively. At rest, Bland-Altman analysis comparing SpO2 with SaO2 (gold standard) demonstrated a bias of 3.8% with limits of agreement of −0.3% to 7.9% (Figure 1, panel A). The vast majority (96.8%) of SpO2 values were higher than the SaO2 determinations and it appears that the lower the SaO2 the more pronounced the gap with SpO2 (Figure 1, panel A).

Table 2.

CPET determinations at rest and peak exercise

| Variable | Resting determinations mean ± SD, n (%) |

Peak exercise determinations mean ± SD, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| n | 751 | 631 |

| ABG Parameters | ||

| pH | 7.42 ± 0.03 | 7.35 ± 0.05 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 87.8 ± 11.4 | 97.9 ± 16.9 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 37.7 ± 4.2 | 34.4 ± 5.9 |

| HCO3 (meq/L) | 24.2 ± 2.2 | 18.7 ± 4.9 |

| SaO2 (%) | 94.4 ± 1.7 | 94.5 ± 2.8 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.9 ± 2.0 | 15.0 ± 4.0 |

| Carboxyhemoglobin (%) | 1.49 ± 0.87 | 1.23 ± 0.77 |

| A-a gradient (mmHg) | 12.8 ± 11.4 | 19.5 ± 4.0 |

| SpO2 − SaO2 (%) | 3.82 ± 2.06 | 2.63 ± 2.75 |

| Spirometry Parameters | ||

| FEV1 (L) | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 2.71 ± 1.05 |

| FEV1 (% of predicted) | 83.8 ± 20.2 | |

| FEV1 % change | −1.9 ± 21.7 | |

| FVC (L) | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 3.40 ± 1.31 |

| FVC (% of predicted) | 86.0 ± 17.9 | |

| FVC % change | −2.2 ± 21.6 | |

| Minute ventilation (L/min) | 11.8 ± 4.1 | 70.0 ± 25.0 |

| CPET Parameters | ||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 82 ± 16 | 141 ± 26 |

| Respiratory rate (rpm) | 17 ± 5 | 42 ± 10 |

| SpO2 (%) | 98.2 ± 1.8 | 97.1 ± 3.2 |

| Oxygen consumption (ml/min) | 319 ± 89 | 1760 ± 632 |

| Oxygen consumption/kg (ml/min/kg) | 3.9 ± 0.9 | 21.6 ± 8.8 |

| Oxygen pulse (ml/min/bpm) | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 12.5 ± 4.0 |

| End tidal CO2 (mmHg) | 33.2 ± 5.0 | 34.3 ± 6.6 |

Abbreviations: ABG = arterial blood gas; BMI = body mass index; CO2 = carbon dioxide; CPET = cardiopulmonary exercise testing; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC = forced vital capacity; HCO3 = bicarbonate; O2 = oxygen; PaO2 = partial pressure of oxygen; PaCO2 = partial pressure of carbon dioxide; SaO2 = arterial hemoglobin oxygen saturation; SpO2 = pulse oximetry; SD = standard deviation. FEV1 and FVC % change refer to the percent variation post-exercise spirometry when compared to the resting determination.

Figure 1. Bland-Altman plots testing the differences between SpO2 and SaO2 at rest and peak exercise.

Plots show the mean difference and 95% confidence interval between SpO2 and SaO2, labeled by smoking status (current smoker, ex-smoker and never smokers). Panel A: determinations at rest. Panel B: determinations at peak exercise.

To better identify the characteristics associated with a larger difference between SpO2 and SaO2 at rest, we compared patients in whom the SpO2 was >= 5% points higher than the SaO2 (n=174, 23%) vs those with <5% points difference (n=577, 77%) (Table 3). We noted that when the difference between SpO2 and SaO2 was >= 5%, patients were older, with a higher proportion of current smokers, higher carboxyhemoglobin and PaCO2 and lower FEV1, end-tidal CO2 and hemoglobin (table 3).

Table 3.

Patient characteristics based on a difference between SpO2 and SaO2 < 5% or >= 5% at rest.

| Variables | SpO2 − SaO2 <5% mean ± SD, n (%) |

SpO2 − SaO2>=5% mean ± SD, n (%) |

P-value (t-test, chi-square) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 577 (76.8) | 174 (23.2) | |

| Age (years) | 53 ±17 | 59 ±13 | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 271 (47.0) | 84 (48.3) | 0.84 |

| Height (cm) | 170.3 ±10.0 | 168.2 ±10.5 | 0.01 |

| Weight (kg) | 84.6 ±21.4 | 82.7 ±22.3 | 0.30 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 ±7.0 | 29 ±6.8 | 0.88 |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | ||

| Current smoker | 20 (3.5) | 48 (27.6) | |

| Ex-smoker | 236 (41.0) | 71 (40.8) | |

| Never smoker | 319 (55) | 55 (31.6) | |

| Reason for CPET testing | <0.001 | ||

| Unexplained dyspnea | 447 (77.6) | 111(63.4) | |

| Pre-operative workup | 118 (20.5) | 62 (35.4) | |

| Exercise induced asthma | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 7 (1.2) | 2 (1.1) | |

| FiO2 (%) | 0.48 | ||

| 21% | 563 (97.6) | 172 (98.8) | |

| 30 % | 14 (2.4) | 2 (1.2) | |

| ABG Parameters | |||

| pH | 7.43 ±0.03 | 7.42 ±0.03 | 0.018 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 90.0 ±10.9 | 80.6 ±10.1 | <0.001 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 37.5 ±4.3 | 38.4 ±3.8 | 0.011 |

| HCO3 (mEq/L) | 24.1 ±2.2 | 24.3 ±1.9 | 0.29 |

| SaO2 (%) | 94.9 ±1.3 | 92.7 ±1.8 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.0 ±2.0 | 13.5 ±2.0 | 0.014 |

| Carboxyhemoglobin (%) | 1.31 ±0.46 | 2.07 ±1.50 | <0.001 |

| A-a gradient (mmHg) | 11.2 ±10.6 | 18.0 ±12.4 | <0.001 |

| Spirometry Parameters | |||

| FEV1 (L) | 2.7 ±0.9 | 2.3 ±0.9 | <0.001 |

| FEV1 (% of predicted) | 85.4 ±19.5 | 78.7 ±21.6 | <0.001 |

| FVC (L) | 3.5 ±1.1 | 3.26 ±1.1 | 0.01 |

| FVC (% of predicted) | 86.3 ±17.8 | 84.7 ±18.5 | 0.27 |

| Minute Ventilation (l/min) | 12.0 ±4.4 | 12.0 ±3.2 | 0.7 |

| CPET Parameters | |||

| Heart Rate (bpm) | 82 ±16 | 83 ±15 | 0.57 |

| Respiratory rate (rpm) | 17 ±5.2 | 18 ±4.5 | 0.11 |

| SpO2 (%) | 97.9 ±1.9 | 99.1 ±1.1 | <0.001 |

| Oxygen consumption (ml/min) | 321 ±91 | 312 ±84 | 0.24 |

| Oxygen consumption/Kg (ml/min/kg) | 3.9 ±0.9 | 3.9 ±0.9 | 0.91 |

| Oxygen pulse (ml/min/bpm) | 4.0 ±1.3 | 3.9 ±1.1 | 0.11 |

| End-tidal CO2 (mmHg) | 33.4 ±4.9 | 32.4 ±5.3 | 0.018 |

Abbreviations: Δ = Difference between, ABG = arterial blood gas; BMI = body mass index; CO2 = carbon dioxide; CPET = cardiopulmonary exercise testing; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second; FiO2= inspired fraction of oxygen; FVC = forced vital capacity; HCO3 = bicarbonate; O2 = oxygen; PaO2 = partial pressure of oxygen; PaCO2 = partial pressure of carbon dioxide; SaO2 = arterial hemoglobin oxygen saturation; SpO2 = pulse oximetry; SD = standard deviation

In a multivariate analysis, we noted that the variables that were independently associated with the difference between SpO2 and SaO2 were current smoker status (β=1.92 for current vs never smokers and β=1.47 for current vs ex-smokers, p<0.001 for both), higher carboxyhemoglobin (per 1 % change, β=0.49, p<0.001), and lower PaO2 (per 1 mmHg change, β=−0.125, p=0.02), FEV1 (per 1 L change, β=−1.15, p=0.01), maximal voluntary ventilation (per 1 L/min change, β=−0.009, p=0.02), and hemoglobin (per 1 g/dL change, β=−0.125, p=0.02). Similar results were noted when we excluded maximal voluntary ventilation (a variable with a VIF close to 4) from the model.

Oximetry at peak exercise

In 120 patients (16%) ABG was obtained at baseline but could not be obtained at peak exercise, therefore, at total 631 (84%) patients had both ABG and SpO2 at peak exercise. Seventy-eight (12.4%) patients had a SpO2 >= 5% points than the SaO2. Bland-Altman analysis showed a bias of 2.6% with limits of agreement of −2.9% and 8.1% (Figure 1 panel B). Interestingly, at peak exercise, several SpO2 values (n= 75, 11.9%) were lower than the SaO2 determinations. At peak exercise, a SpO2 >= 5% point higher than the SaO2 was associated with older age, lower height and weight, current smoker status, higher PaCO2, bicarbonate, and carboxyhemoglobin, lower hemoglobin, FVC, FEV1, maximum heart rate, oxygen consumption, and O2 pulse (Table 4). In multivariate analysis, the variables independently associated with the difference between SpO2 and SaO2 at peak exercise were lower FVC (per 1 L change, β=−0.27, p=0.001) and carboxyhemoglobin (per 1 % change, β=0.78, p<0.001).

Table 4.

Patient characteristics based on a difference between SpO2 and SaO2 < 5% or >= 5% at peak exercise.

| Variables | SpO2 − SaO2 <5% mean ± SD, n (%) |

SpO2 − SaO2 >=5% mean ± SD, n (%) |

P-value (t-test, chi-square) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 553 (87.6) | 78 (12.4) | |

| Age (years) | 54 ±16 | 61 ±14 | 0.001 |

| Male gender | 276 (49.9) | 32 (41.0) | 0.178 |

| Height (cm) | 170.7 ±10.0 | 166.1 ±9.3 | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 85.9 ±21.4 | 79.0 ±21.3 | 0.007 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.4 ±6.8 | 28.5 ±7.0 | 0.12 |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | ||

| Current smoker (%) | 29 (5.3) | 21 (26.9) | |

| Ex-smoker (%) | 235 (42.6) | 39 (50.0) | |

| Never smoker (%) | 299 (52.2) | 18 (23.1) | |

| Reason for CPET testing | |||

| Unexplained dyspnea | 424 (78.2) | 49 (55.1) | |

| Pre-operative workup | 110 (20.3) | 38 (42.7) | |

| Exercise induced asthma | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 5 (0.9) | 2 (2.2) | |

| FiO2 (%) | 1.00 | ||

| 21% | 542 (98.0) | 76 (97.4) | |

| 30% | 11 (2.0) | 2 (2.6) | |

| ABG Parameters | |||

| pH | 7.35 ±0.05 | 7.35 ±0.05 | 0.494 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 100.2 ±15.9 | 81.8 ±15.0 | <0.001 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 34.0 ±5.8 | 36.8 ±5.7 | <0.001 |

| HCO3 (mEq/L) | 18.5 (5.0 | 20.0 ±3.3 | 0.011 |

| SaO2 (%) | 94.9 (2.2 | 91.4 ±4.0 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 15.0 (4.3 | 14.0 ±2.0 | 0.026 |

| Carboxyhemoglobin (%) | 1.14 ±0.59 | 1.85 ±1.37 | <0.001 |

| A-a gradient (mmHg) | 17.8 ±13.2 | 32.0 ±13.7 | <0.001 |

| Spirometry Parameters | |||

| FEV1 (L) | 2.7 ±1.0 | 2.1 ±1.1 | <0.001 |

| FEV1(% change) | -1.1 ±19.8 | -8.0 ±31.8 | 0.009 |

| FVC (L) | 3.5 ±1.3 | 2.8 ±1.4 | 0.002 |

| FVC (% change) | -1.3 ±19.6 | -8.6 ±31.7 | 0.005 |

| Minute ventilation (l/min) | 71.0 ±25.0 | 62.0 ±22.4 | <0.001 |

| CPET Parameters | |||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 142 ±26 | 132 ±24 | <0.001 |

| Respiratory rate (rpm) | 42 ±10 | 42 ±10 | 0.98 |

| SpO2 (%) | 97.0 ±3.2 | 97.8 ±3.0 | 0.041 |

| Oxygen consumption (ml/min) | 1813 ±629 | 1387 ±519 | <0.001 |

| Oxygen consumption/kg (ml/min/kg) | 22.0 ±9.0 | 18.2 ±7.0 | <0.001 |

| Oxygen pulse (ml/min/bpm) | 12.8 ±4.0 | 10.6 ±3.4 | <0.001 |

| End-tidal CO2 (mmHg) | 32.5 ±5.3 | 32.0 ±4.7 | 0.639 |

Abbreviations: ABG = arterial blood gas; BMI = body mass index; CO2 = carbon dioxide; CPET = cardiopulmonary exercise testing; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second; FiO2= inspired fraction of oxygen; FVC = forced vital capacity; HCO3 = bicarbonate; O2 = oxygen; PaO2 = partial pressure of oxygen; PaCO2 = partial pressure of carbon dioxide; SaO2 = arterial hemoglobin oxygen saturation; SpO2 = pulse oximetry; SD = standard deviation

A decrease in SaO2 >= 4% during exercise is commonly considered clinically significant (16). At total of 26 (4%) patients had a decrease in SaO2 >= 4% at maximum exercise and of them 20 (77%) had a drop in SpO2 >= 4%. A drop in SpO2 >= 4% had false positive and negative rates of 10% and 1%, respectively, for detecting a decrease in SaO2 of >= 4%.

Discussion

The present study improves the understanding of the magnitude, direction and potential sources of error of pulse oximetry during exercise. It validates that carboxyhemoglobin is an important factor in explaining the difference between SpO2 and SaO2, and supports obtaining ABG determinations in certain patients, particularly current smokers. In addition we noted that a small proportion of patients had a falsely low SpO2 reading during exercise that if not confirmed by ABG may lead to unnecessary testing.

The importance of pulse oximetry as a rapid, non-invasive tool to assess oxygenation cannot be understated. However, this methodology is susceptible to measuring error due to a variety of conditions. In general, the margin of error of SpO2 is within 2% to 3% of the SaO2 (14, 18, 19). Taking advantage of the large number of data collected and investigations performed at the time of CPET in our institution, we sought to test the accuracy of SpO2 to estimate SaO2 both at rest and at peak exercise with a particular focus in identifying factors accounting for the discrepancy between measurements.

In our laboratory and using the equipment described, we found that the bias between SpO2 and SaO2 did not increase during exercise (3.8% at baseline and 2.6% during the exercise), with the majority of the SpO2 determinations overestimating SaO2, particularly when the SaO2 was below 90% or patients were current smokers. At peak exercise, the limit of agreement between SpO2 and SaO2 widened by one third from a gap of 8.25 to 10.99%, with more determinations in which SpO2 was lower than SaO2, reflecting limitations in the accurate determination of SpO2, particularly during exercise. We identified several patient’s characteristics associated with >= 5% points higher SpO2 compared to SaO2, such as older age, current smoker status, lower FEV1, and higher PaCO2 and carboxyhemoglobin. In addition, during peak exercise, patients with a larger gap between SpO2 and SaO2 had lower heart rate, lower oxygen consumption and oxygen, pulse.

A few studies that included a small number of healthy patients tested the validity of pulse oximetry during maximal exercise and noted an under- (26,27) or overestimation (28,29) of the SaO2, with some suggesting a better precision when using a forehead sensor (26). To our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate the inconsistencies between SpO2 measured with a forehead probe and SaO2 in an outpatient cohort both at rest and peak exercise. The majority of our patients underwent CPET for unexplained dyspnea or as part of pre-operative work-up. Other studies have examined the discordance between SpO2 and SaO2; however, these cohorts consisted of critically ill inpatients or patients who recently underwent surgery (3, 8, 14, 20, 21, 22). Similar to these other investigations we noted that the bias between SpO2 and SaO2 at rest was 3.8%.

Motion artifact is one of the major causes of inaccurate pulse oximetry readings. We used a forehead probe to reduce the possibility of motion artifact and errors caused as a result of gripping the bicycle handlebars (15). We paid particular attention to the quality of SpO2 waveform and test its accuracy against a second forehead probe. An accurate determination of SpO2 is critical, since desaturations during CPET can lead to further invasive testing and expense. Although at rest we noted that SpO2 systematically overestimates SaO2, at peak exercise we observed that 10 (1.6%) patients had an SpO2 below the SaO2, in a range that could be considered hypoxemia (SpO2 < 90%). In addition, in 10% of the patients we noted a drop in SaO2 >= 4% during maximal exercise, at odds with the corresponding changes in SaO2. These discrepancies could be related to forehead hypoperfusion, venous congestion with venous pulsations (30) or inaccuracies in the SpO2 determination due to head motion during the activity. Given these findings and the additional information provided by the test, we recommend obtaining an ABG both at baseline and particularly at peak exercise during CPET (unless contraindicated) either using repeated punctures or an arterial line. ABG collection adds discomfort and an extra expense to patients. In addition, the ABG needs to be obtained at maximum exercise, since values can rapidly change in the recovery phase. Taking this caveats into consideration, we believe in confirming unexpected SpO2 values with ABG analysis, particularly during exercise.

One of the main factors involved in the falsely high SpO2 readings is carboxyhemoglobin (13), which absorbs light at approximately the same spectrum as oxyhemoglobin. Therefore, the determination presented by the pulse oximeter is a summation of oxyhemoglobin plus carboxyhemoglobin. This is particularly relevant in smokers, as noted in our analyses, and may explain the association with lower FEV1 and higher PaCO2. In our cohort, carboxyhemoglobin was an important factor, however, it explained less than half of the difference between SpO2 and SaO2. Co-oximetry, which measures light absorbance at multiple wave lengths, is certainly needed if this source of error is suspected. In addition, data obtained at rest showed that PaO2 and hemoglobin were inversely associated with the difference between SpO2 and SaO2; variables that may impact the accuracy of the pulse oximetry.

Our study is not without limitations: a) in 120 (16%) patients we could not obtain peak exercise ABG, b) pulse oximetry results were obtained with a forehead probe to minimize motion artifact (23), it is unclear if our findings can be extrapolated to finger probes, c) SpO2 readings may vary according to the model of pulse oximeter used (13, 15, 25), and d) race was not recorded.

Conclusion

In the present study, pulse oximetry commonly underestimated the arterial oxygen saturation. Increased carboxyhemoglobin levels are major contributors to the difference between arterial and pulse oxygen saturation both at rest and peak exercise; a finding particularly relevant in smokers.

Acknowledgments

The results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation, and statement that results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

Funding Sources: A.R.T. is supported by NIH grant # R01HL130307.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statements:

Mona Ascha BS: The author has no significant conflicts of interest with any companies or organization whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Anirban Bhattacharyya MD: The author has no significant conflicts of interest with any companies or organization whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Jose A Ramos RT: The author has no significant conflicts of interest with any companies or organization whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Adriano R Tonelli MD, MSc: The author has no significant conflicts of interest with any companies or organization whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Contributions of authors:

Mona Ascha BS: Participated in writing and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and final approval of the manuscript submitted.

Anirban Bhattacharyya MD: Participated in writing, collection of data, statistical analysis, writing and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and final approval of the manuscript submitted.

Jose A Ramos RT: Participated in collection of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and final approval of the manuscript submitted.

Adriano R. Tonelli MD, MSc: Participated in the conception of the manuscript, collection of data, writing and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and final approval of the manuscript submitted. Dr Tonelli is the guarantor of the paper, taking responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article.

References

- 1.Kacmarek RK, Stoller JK, Heuer AJ. Egan’s Fundamentals of Respiratory Care. 10th. Mosby; 2012. Analysis and Monitoring of Gas Exchange; p. 398. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman KR, Liu FLW, Watson RM, Rebuck AS. Range of accuracy of two wavelength oximetry. Chest. 1986;89:540–542. doi: 10.1378/chest.89.4.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeserson E, Goodgame B, Hess JD, et al. Correlation of Venous Blood Gas and Pulse Oximetry With Arterial Blood Gas in the Undifferentiated Critically Ill Patient. J Intensive Care Med. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0885066616652597. E-publication ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kacmarek RK, Stoller JK, Heuer AJ. Egan’s Fundamentals of Respiratory Care. 10th. Mosby; 2012. Analysis and Monitoring of Gas Exchange; p. 408. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kacmarek RK, Stoller JK, Heuer AJ. Egan’s Fundamentals of Respiratory Care. 10th. Mosby; 2012. Analysis and Monitoring of Gas Exchange; pp. 408–409. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moyle JT. Uses and abuses of pulse oximetry. Arch Dis Child. 1996;74(1):77–80. doi: 10.1136/adc.74.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bierman MI, Stein KL, Snyder JV. Pulse oximetry in the postoperative care of cardiac surgical patients. A randomized controlled trail. Chest. 1992;102(5):1367–70. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.5.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson JP, Venkatesh B, Patla V. Misleading information from pulse oximetry and the usefulness of continuous blood gas monitoring in a post cardiac surgery patient. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21(5):437–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01707413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vicenzi MN, Gombotz H, Krenn H, Dorn C, Rehak P. Transesophageal versus surface pulse oximetry in intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(7):2268–70. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibáñez J, Velasco J, Raurich JM. The accuracy of the Biox 3700 pulse oximeter in patients receiving vasoactive therapy. Intensive Care Med. 1991;17(8):484–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01690773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jubran A, Tobin MJ. Reliability of pulse oximetry in titrating supplemental oxygen therapy in ventilator-dependent patients. Chest. 1990;97(6):1420–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.6.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter BG, Carlin JB, Tibballs J, Mead H, Hochmann M, Osborne A. Accuracy of two pulse oximeters at low arterial hemoglobin-oxygen saturation. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(6):1128–33. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199806000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnapp LM, Cohen NH. Pulse oximetry uses and abuses. Chest. 1990;98(5):1244–1250. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.5.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van de louw A, Cracco C, Cerf C, et al. Accuracy of pulse oximetry in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(10):1606–13. doi: 10.1007/s001340101064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamaya Y, Bogaard HJ, Wagner PD, Niizeki K, Hopkins SR. Validity of pulse oximetry during maximal exercise in normoxia, hypoxia, and hyperoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92(2):162–168. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00409.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Thoracic Society.; American College of Chest Physicians. ATS/ACCP Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Jan 15;167(2):211–77. doi: 10.1164/rccm.167.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. ATS/ERS Task Force. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005 Aug;26(2):319–38. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wouters PF, Gehring H, Meyfroidt G, et al. Accuracy of pulse oximeters: the European multi-center trial. Anesth Analg. 2002;94(1 Suppl):S13–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webb RK, Ralston AC, Runciman WB. Potential errors in pulse oximetry. II. Effects of changes in saturation and signal quality. Anaesthesia. 1991;46(3):207–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1991.tb09411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shibata O, Kawata K, Miura K, Shibata S, Terao Y, Sumikawa K. Discrepancy between SpO2 and SaO2 in a patient with severe anemia. J Anesth. 2002;16(3):258–60. doi: 10.1007/s005400200037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed S, Siddiqui AK, Sison CP, Shahid RK, Mattana J. Hemoglobin oxygen saturation discrepancy using various methods in patients with sickle cell vaso-occlusive painful crisis. Eur J Haematol. 2005;74(4):309–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2004.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart KG, Rowbottom SJ. Inaccuracy of pulse oximetry in patients with severe tricuspid regurgitation. Anaesthesia. 1991;46(8):668–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1991.tb09720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomlinson AR, Levine BD, Babb TG. Low Pulse Oximetry Reading: Time for Action or Reflection? Chest. 2017;151(4):735–736. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schnapp LM, Cohen NH. Pulse oximetry. Uses and abuses. Chest. 1990;98(5):1244–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.5.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thilo EH, Andersen D, Wasserstein ML, Schmidt J, Luckey D. Saturation by pulse oximetry: comparison of the results obtained by instruments of different brands. J Pediatr. 1993;122(4):620–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83549-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaya Y, Bogaard HJ, Wagner PD, Niizeki K, Hopkins SR. Validity of pulse oximetry during maximal exercise in normoxia, hypoxia, and hyperoxia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2002;92(1):162–168. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00409.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norton LH, Squires B, Craig NP, McLeay G, McGrath P, Norton KI. Accuracy of pulse oximetry during exercise stress testing. Int J Sports Med. 1992;13(7):523–527. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wood RJ, Gore CJ, Hahn AG, et al. Accuracy of two pulse oximeters during maximal cycling exercise. Aust J Sci Med Sport. 1997;29(2):47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orenstein DM, Curtis SE, Nixon PA, Hartigan ER. Accuracy of three pulse oximeters during exercise and hypoxemia in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 1993;104(4):1187–1190. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.4.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sami HM, Kleinman BS, Lonchyna VA. Central venous pulsations associated with a falsely low oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry. J Clin Monit. 1991;7(4):309–312. doi: 10.1007/BF01619351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]