Two decades of research on adult attachment and psychopathology, suggest that while various indicators of attachment insecurity increase risk for psychopathology, these findings are generally vulnerable to correlational designs, lack of specificity and relatively small effect sizes1,2. Studies of the effects of early indicators of attachment insecurity on subsequent psychopathology have also yielded small effect sizes and general lack of specificity with regards to diagnostic outcomes3–5. As a result, there is a need for more nuanced models that hold the potential for better understanding how adult attachment is implicated in the development and maintenance of psychopathology. These models will benefit from moving from a view of attachment as an aspect of personality toward a more dynamic model that accounts for how personality continually transacts with dyadic communication in attachment relationships. We propose a model of attachment and psychopathology that is premised on an insecure cycle between Internal Working Models (IWM) and mistuned communication with relationship partners. When dyadic communication confirms or amplifies insecure aspects of personality, the contribution of attachment to the development or maintenance of psychopathology is compounded. Alternatively, secure aspects of IWMs or dyadic communication can moderate the effects of the secure cycle on the management and treatment of psychiatric disorders.

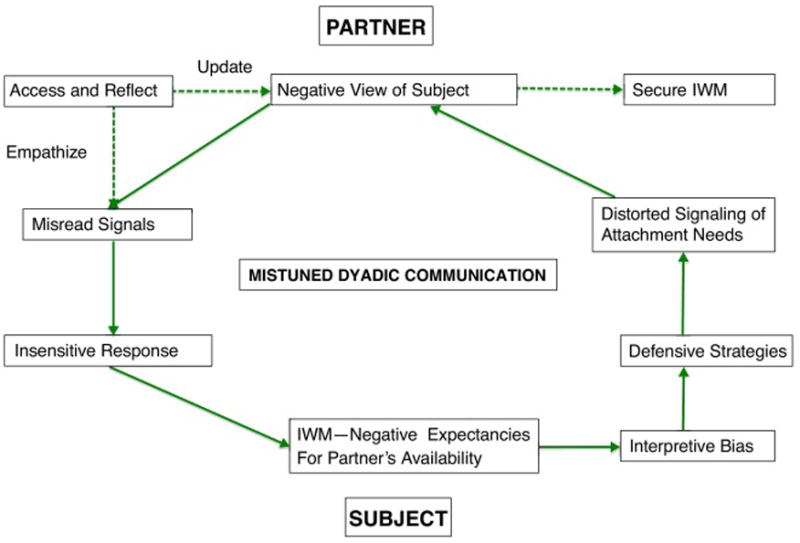

Our model of the insecure cycle begins with identifying three components of insecure IWMs: negative expectancies, interpretative biases, and defensive strategies. We then consider a continuum of insensitive or mistuned patterns of dyadic communication ranging from abandonment to subtle forms of disengagement that serve to perpetuate and confirm insecure IWMs. In this view, insecure expectancies create a series of vulnerabilities that increase the likelihood of exposure to threats to a partner’s availability and responsiveness. Reduced capacity to respond to these threats in turn, creates a recursive cycle in which the individual interprets and responds to communications in ways that maintain or exacerbate the perception of threat, confirm expectancies and activate defensive strategies in an attempt to reduce anxious feelings. Alternatively, when insecure aspects of personality are met with sensitive responses from a relationship partner, negative expectancies may be disconfirmed. Similarly, when IWMs are organized by more confident expectations, communication difficulties are more likely to be repaired, the secure cycle disrupted and the risk for psychopathology reduced6.

Our view of the insecure cycle illustrates a more general shift in attachment research from approaches that focus primarily on insecurity as a relatively stable trait-like aspect of personality, toward a more dynamic transactional model that focuses on within person variability7, relationship specificity8 and malleability to change9. This more dynamic view of attachment processes points to substantial between person variability in beliefs about insensitive or rejecting caregivers and to an approach that views attachment security and insecurity as a continuum of risk for the development and maintenance of psychopathology. This move toward a more dynamic view of attachment processes provides a framework for more individualized assessment of attachment related risk and points to the need to develop and test experimental interventions that are designed to increase security in specific components of the insecure cycle that in ways that may reduce risk for psychopathology.

Conceptualizing Intrapersonal Risk–Attachment Related Diatheses

The components of insecure IWM’s, negative expectancies, interpretative biases, and defensive strategies are depicted in Figure 1. Distinguishing these components may help to identify specific transdiagnostic mechanisms that increase risk for several clinical disorders and that may become targets for therapeutic interventions10. At the heart of insecure internal working models are negative expectancies that attachment figures will not be available or responsive at times of danger or challenge11. These expectancies can be inferred from attachment behavior or from scripts of adult attachment narratives12. Negative expectancies for available and responsive care typically generate anxious or depressed feelings that have been linked to trait-levels of neuroticism and pessimism2. These negative expectancies or forecasts about a relationship partner’s behavior support interpretative biases in which positive signals of a partner’s availability are ignored or minimized and subtle cues of insensitive response are amplified into perceived threats to a partner’s availability10,13–16. As a result, relatively common daily fluctuations in the degree to which a partner is available and responsive will be interpreted as confirming negative generalizations about the partner and corresponding negative feelings about the self.

Figure 1.

Defensive strategies have represented the predominant focus of adult attachment literature with personality conceptualized as either states of mind with respect to attachment17 or attachment styles2. These defensive strategies have been broadly conceived as based upon either deactivating or hyperactivating the attachment system in order to reduce anxious feelings that accompany negative expectancies. Dimensional ratings of these strategies have been used as global indicators of IWMs in the two major streams of the adult attachment assessment, attachment styles and states of mind. In early parent-child relationships, these strategies were thought to serve the interpersonal function of altering the output of the child’s attachment system to reduce potential conflict with an insensitive caregiver or to maintain the child’s access to an inconsistent or inattentive caregiver18. Extension of these strategies to assessments of adult attachment have emphasized the intrapersonal emotion regulation function of reducing the anxiety and fear that accompanies negative expectancies for a caregiver’s lack of availability19.

Deactivating and hyperactivating strategies can be conceptualized as forms of attention deployment that serve both interpersonal and intrapersonal functions. Deactivating strategies divert attention from attachment needs in both self and others20. At the intrapersonal level, diversionary strategies restrict the individual’s access to feelings that would motivate care seeking behavior while at the interpersonal level, this attentional strategy reduces the individual’s capacity to attend to and read attachment signals from others. Hyperactivating strategies also reduce an individual’s ability to flexibly deploy attention. At the intrapersonal level excessive focus on attachment needs and feelings restricts access to exploratory or competency motivations20. At the interpersonal level, these attentional strategies increase vigilance toward caregivers in ways that create potential burden and reduce the caregiver’s capacity to effectively respond to the individual’s needs and signals. Self-perceptions of burdening caregivers have been linked to increased risk of suicidality21. Both types of defensive strategies reduce the individual’s capacity to reappraise interpretations of self and other22 and restrict an individual’s ability to redeploy attentional resources to reflect upon or accurately mentalize their own or their partner’s thoughts and feelings22–24.

Conceptualizing the Interpersonal Context—Stress and Attuned Communication

The degree to which insecure IWM’s confer risk for psychopathology depends on the extent to which emerging patterns of communication in an attachment dyad confirm or disconfirm intrapersonal vulnerabilities. The quality of these emergent patterns of communication depends on partners’ relationship histories as well as evolving perceptions of self and other in the relationship25. For while an insecure individual will bring negative expectancies, interpretative biases and defensive strategies to interactions with a relationship partner, the partner’s interpretations and responses offer multiple opportunities to alter expectancies, disconfirm interpretative biases and reduce anxieties that motivate defensive strategies26. If a relationship partner can accommodate, reappraise and empathize with an insecure individual’s needs, a relatively stable pattern of sensitive and supportive communication can be established27. Although this more secure pattern reduces risk for psychopathology, the insecure individual may remain more vulnerable to major stressful life events that tests the dyad’s capacity to maintain sensitive and supportive communication.

Stressful interpersonal events have been consistently identified as potential precipitants of adult psychopathology28. For instance, the events that are most predictive of major depressive disorder involve rejection, betrayal or break-ups in close adult relationships. In relationships in which a partner finds the relationship unsatisfactory and responds with hostile or rejecting communications, an insecure individual not only confirms negative expectancies about the partner but also amplifies perceptions of the partner as a potential source of threat or abandonment. Increased fear and perception of threat, in turn, make defensive strategies less effective in reducing fear and anxiety and contribute to an escalation in the anxious cycle that increases vulnerability for psychopathology. When insecure IWMs are combined with hostile or rejecting patterns of communication in close relationships, vulnerabilities that predispose an individual toward developing anxious, depressed, or anti-social symptoms are more likely to cross thresholds for psychiatric diagnosis. In these circumstances, the symptoms can be viewed as signals that the insecure cycle is breaking down and no longer adequate for maintaining a stable equilibrium for the individual or the relationship partner29.

Attachment related risk for psychopathology is greatest when chronic hostile communication results in relationship break-up or when an individual experiences chronic difficulty in maintaining an attachment bond. Careful differentiation between chronic and episodic stressful life events has indicated that individuals who are exposed to chronic romantic stress characterized either by persistent lack of support and rejection in a relationship or by consistent difficulty initiating any close relationship are at the greatest risk for developing major affective disorders. Long-term lack of connectedness leaves the individual isolated in ways that increase the risk associated with insecure IWM’s. This social isolation has also been consistently identified as one of the key interpersonal factors for suicidal ideation and behaviors. Additional candidates for more extreme risk for psychopathology include abusive behaviors, abandonment or targeted rejection3,30.

A Dynamic Transactional Model of Attachment and Psychopathology

Attachment research has largely neglected the large proportion of insecure individuals who do not develop clinically significant psychological problems. This neglect raises questions about how aspects of security can be introduced into the insecure cycle in ways that stabilize attachment relationships and moderate risk for psychopathology. Consideration of secure elements in the insecure cycle suggests that there may be considerable heterogeneity in the extent to which an individual’s insecure cycle is capable of accommodating discrepant elements and open to change. At the intrapersonal level, the discrepant secure components can be introduced to IWMs at the levels of expectancies, biases or defensive strategies13. For instance, a study of individual’s trusting or secure interpretations of their partner’s responsiveness, resulted in reductions in deactivating attentional strategies over time31. Similarly, analysis of Main and Goldwyn’s AAI classifications, points to the possibility that non-defensive secure attentional strategies inferred from the coherence of interview discourse can coincide with episodic memories reflecting negative expectancies for caregiver availability. This discrepancy between underlying expectancies and attentional strategies in the interview has been associated with more adaptive outcomes17.

The dynamic nature of the insecure cycle is also evident in research that differentiates between state and trait views of attachment insecurity. Intervention studies suggest that temporary changes in IWM’s can be facilitated by experimental interventions that target defensive strategies32, interpretation biases33 or expectancies for caregiver availability34. Priming studies illustrate the promise of interventions that target automatic expectancies and interpretative biases rather than defensive strategies7,33. The advantage of interventions that target pre-conscious or automatic levels of processing is that these interventions can introduce changes that do not challenge defensive attentional strategies. Reflection and updating of models may follow but is not required for moderating the insecure cycle or increasing the individual’s overall level of security35. The challenge for interventions that target state fluctuations in attachment processes is to demonstrate that movement toward more secure functioning is sustained over time.

Sensitive and responsive communication is a particularly potent moderator of the insecure cycle36. In a study of adult romantic relationships, Overall and colleagues showed that although avoidant partners were more likely to show anger and withdrawal during discussions of partners’ desired changes in each other. However, more dynamic analyses of within person change over the course of the discussion revealed that these same subjects’ anger and withdrawal were attenuated or responsive to their partners’ softening communications. These dyadic regulatory processes point to the degree to which partners’ can accommodate each other’s insecure IWMs in ways that activate reparative processes and result in more cooperative and mutually attuned dyadic communication37. The importance of adapting communications to the vulnerabilities associated with insecure IWM’s has long been a mainstay of Bowlby’s theory of therapeutic change38. In a study of clients in 16 weeks of psychotherapy, clients whom perceived their therapists’ as more empathic over the course of treatment showed reductions in their attachment insecurity over the course of treatment26.

Conclusion

Over the past decade, research on attachment and psychopathology has moved toward a more dynamic understanding of the way in which IWM are in constant interplay with interpersonal communication. For clinicians, this view serves two valuable purposes. First, the insecure cycle points to how risk for psychopathology can be dramatically amplified by vicious self-perpetuating cycles of insecure IWMs that are confirmed and validated by insensitive, stressful or rejecting interpersonal communication. This model provides a guide assessing presenting symptoms and determining the extent to which attachment issues need to be considered in treatment planning. Second, the more dynamic model provides a more nuanced approach to identifying points of entry in the insecure cycle that can be used to moderate risk for psychopathology. For researchers, the more dynamic view of attachment points to the continued need to study intra-individual variability in attachment processes and to investigate the interface between self-regulatory and dyadic regulatory processes in attachment relationships39.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Stovall-McClough, Dozier M. Handbook of Attachment. Third. Guilford Publications; 2016. Attachment States of Mind and Psychopathology in Adulthood. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in Adulthood. Second. Guilford Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin J, Raby KL, Labella MH, Roisman GI. Childhood abuse and neglect, attachment states of mind, and non-suicidal self-injury. Attachment & Human Development. 2017;19(5):425–446. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2017.1330832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fearon RMP, Roisman GI. Attachment theory: progress and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2017;15:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boswell JF, Anderson LM, Barlow DH. An idiographic analysis of change processes in the unified transdiagnostic treatment of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(6):1060–1071. doi: 10.1037/a0037403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraley RC. A connectionist approach to the organization and continuity of working models of attachment. Journal of Personality. 2007;75(6):1157–1180. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosmans G. An Experimental Evaluation of the State Adult Attachment Measure: The Influence of Attachment Primes on the Content of State Attachment Representations. 2014 Jun;:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crowell JA, Fraley RC, Roisman GI. Handbook of Attachment. Third. Guilford Publications; 2016. Measurement of Individual Differences in Adult Attachment. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobak R, Zajac K, Herres J, Krauthamer Ewing ES. Attachment based treatments for adolescents: the secure cycle as a framework for assessment, treatment and evaluation. Attachment & Human Development. 2015;17(2):220–239. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2015.1006388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10**.Ein-Dor T, Viglin D, Doron G. Extending the Transdiagnostic Model of Attachment and Psychopathology. Front Psychol. 2016;7:245–246. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00484. Provides hypotheses about potential mechanisms linking attachment insecurity to psychopathology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowlby J, Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Separation: Anxiety and Anger. 1973;2 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waters TEA, Ruiz SK, Roisman GI. Origins of Secure Base Script Knowledge and the Developmental Construction of Attachment Representations. Child Development. 2016 Jun; doi: 10.1111/cdev.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Overall NC, Fletcher GJO, Simpson JA, Fillo J. Attachment insecurity, biased perceptions of romantic partners’ negative emotions, and hostile relationship behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(5):730–749. doi: 10.1037/a0038987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosmans G. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Children and Adolescents: Can Attachment Theory Contribute to Its Efficacy? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2016;19(4):310–328. doi: 10.1007/s10567-016-0212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosmans G, Koster EHW, Vandevivere E, Braet C, De Raedt R. Young Adolescent’s Confidence in Maternal Support: Attentional Bias Moderates the Link Between Attachment-Related Expectations and Behavioral Problems. Cogn Ther Res. 2013;37(4):829–839. doi: 10.1007/s10608-013-9526-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16**.Dykas MJ, Cassidy J. Attachment and the processing of social information across the life span: Theory and evidence. Psychol Bull. 2011;137(1):19–46. doi: 10.1037/a0021367. An excellent review of the evidence for how IWM’s guide the selective processing of social information. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hesse E. Handbook of Attachment. Third. 1999. Handbook of Attachment; p. 1068. (Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. Theory). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Main M. Cross-Cultural Studies of Attachment Organization: Recent Studies, Changing Methodologies, and the Concept of Conditional Strategies. Human Development. 1990;33(1):48–61. doi: 10.1159/000276502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malik S, Wells A, Wittkowski A. Emotion regulation as a mediator in the relationship between attachment and depressive symptomatology_ A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2015;172(C):428–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobak RR, Cole HE, Ferenz Gillies R, Fleming WS, Gamble W. Attachment and Emotion Regulation during Mother-Teen Problem Solving: A Control Theory Analysis. Child Development. 1993;64(1):231–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katznelson H. Reflective functioning: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34(2):107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esbjørn BH, Pedersen SH, Daniel SIF, Hald HH, Holm JM, Steele H. Anxiety levels in clinically referred children and their parents: Examining the unique influence of self-reported attachment styles and interview-based reflective functioning in mothers and fathers. Br J Clin Psychol. 2013;52(4):394–407. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borelli JL, Compare A, Snavely JE, Decio V. Reflective functioning moderates the association between perceptions of parental neglect and attachment in adolescence. Psychoanalytic Psychology. 2015;32(1):23–35. doi: 10.1037/a0037858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pietromonaco PR, Collins NL. Interpersonal mechanisms linking close relationships to health. Am Psychol. 2017;72(6):531–542. doi: 10.1037/amp0000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson JC, Steckley PL, McMullen EJ. The role of empathy in promoting change. Psychotherapy Res. 2014;24(3):286–298. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.802823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Girme YU, Overall NC, Simpson JA, Fletcher GJO. “All or nothing”: attachment avoidance and the curvilinear effects of partner support. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(3):450–475. doi: 10.1037/a0038866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28*.Vrshek-Schallhorn S, Stroud CB, Mineka S, et al. Chronic and episodic interpersonal stress as statistically unique predictors of depression in two samples of emerging adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2015;124(4):918–932. doi: 10.1037/abn0000088. Summarizes and presents new evidence for how interpersonal stress contributes to depressive disorders. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farmer AS, Kashdan TB. Stress sensitivity and stress generation in social anxiety disorder: a temporal process approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2015;124(1):102–114. doi: 10.1037/abn0000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy MLM, Slavich GM, Chen E, Miller GE. Targeted rejection predicts decreased anti-inflammatory gene expression and increased symptom severity in youth with asthma. Psychological science : a journal of the American Psychological Society/APS. 2015;26(2):111–121. doi: 10.1177/0956797614556320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arriaga XB, Kumashiro M, Finkel EJ, VanderDrift LE, Luchies LB. Filling the Void: Bolstering Attachment Security in Committed Relationships. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2014;5(4):398–406. doi: 10.1177/1948550613509287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alex Brake C, Sauer-Zavala S, Boswell JF, Gallagher MW, Farchione TJ, Barlow DH. Mindfulness-Based Exposure Strategies as a Transdiagnostic Mechanism of Change: An Exploratory Alternating Treatment Design. Behavior Therapy. 2016;47(2):225–238. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carnelley KB, Otway LJ, Rowe AC. The Effects of Attachment Priming on Depressed and Anxious Mood. Clin Psychol Sci. 2016;4(3):433–450. doi: 10.1177/2167702615594998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stanton SCE, Campbell L, Pink JC. Benefits of positive relationship experiences for avoidantly attached individuals. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2017;113(4):568–588. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arriaga XB, Kumashiro M, Simpson JA, Overall NC. Revising Working Models Across Time: Relationship Situations That Enhance Attachment Security. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2018;22(1):71–96. doi: 10.1177/1088868317705257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36**.Simpson JA, Overall NC. Partner Buffering of Attachment Insecurity. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014;23(1):54–59. doi: 10.1177/0963721413510933. Specifies processes through which partners in attachment relationship may buffer the adverse effects of an individual’s insecure IWM’s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37**.Overall NC, Simpson JA, Struthers H. Buffering attachment-related avoidance: Softening emotional and behavioral defenses during conflict discussions. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2013;104(5):854–871. doi: 10.1037/a0031798. A model study demonstrating the dynamic interplay between IWM’S and dyadic communication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowlby J. A Secure Base. Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Overall NC, Simpson JA. Attachment and Dyadic Regulation Processes. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;1:61–666. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]