Abstract

Background

The outcome of colon cancer patients without lymph node metastasis is heterogeneous. Searching for new prognostic markers is warranted.

Methods

One hundred twenty stage I–II colon cancer patients who received complete surgical excision during 1995–2004 were selected for this biomarker study. Immunohistochemical method was used to assess p53, epidermal growth factor receptor, MLH1, and MSH2 status. KRAS mutation was examined by direct sequencing.

Results

Thirty three patients (27.5%) developed metachronous metastasis during follow up. By multivariate analysis, only female gender (p = 0.03), high serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level (≧5 ng/ml) (p = 0.04), and MLH1 overexpression (p = 0.003) were associated with the metastasis group. The 5-year-survival rate were also significantly lower for female gender (71.7% versus 88.9%, p = 0.025), high CEA level (64.9% versus 92.4%, p < 0.001), and MLH1 overexpression (77.5% versus 94.4%, p = 0.039). In contrast, MSH2 overexpression was associated with better survival, 95.1% versus 75.5% (p = 0.024).

Conclusions

The reversed prognostic implications in the overexpression of MLH1 and MSH2 for stage I–II colon cancer patients is a novel finding and worthy of further confirmation.

Keywords: Colon cancer, MLH1, MSH2, CEA, Mismatch repair

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

The outcome of colon cancer patients without lymph node metastasis is heterogeneous and inconclusive. Searching for new prognostic markers is warranted.

What this study adds to the field

This is a study on 120 surgically treated stage I/II colon cancer patients for various biomarker study, which include: p53, EGFR, MLH1, and MSH2 expression and KRAS mutation. The results demonstrated that high CEA level and overexpression of MLH1 were associated with shorter survival and overexpression of MSH2 were associated with longer survival. The serum CEA level combined with MLH1 and MSH2 expression status could help in selecting stage I/II colon cancer patients with higher risk for tumor recurrence.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains the third place in cancer incidence around the world and affects more than 1 million individuals annually with nearly 33% disease-related mortality rate in developed countries [1], [2]. The therapeutic strategies for patients with CRC are mainly guided by adequate tumor staging. Localized tumor diseases, i.e. tumors of AJCC/UICC (American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control) stage I and II (T1-4N0M0), are considered to be cured by radical tumor resection with a 5-year overall survival more than 70%. Unfortunately, about 10–20% of these patients develops local recurrence or metachronous distant metastasis and follows a dismal outcome [3], [4]. Therefore, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines make recommendations about adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II CRC patents on the basis of the relevant clinical risk factors, including poor differentiation, T4 stage, tumor perforation, and inadequate lymphadenectomy [5], [6].

Aside from the clinical parameters, much effort have been applied in searching for molecular biomarkers of CRC, which could help for selecting the high-risk patients who might be benefit from receiving postoperative chemotherapy [7], [8]. Among the various biomarkers, p53 gene status, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression, V-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) mutation, and microsatellite instability (MSI) genotype have been studied most extensively. However, the significance of these biomarkers is still controversial. A meta-analysis for p53 protein expression and mutation reported that both were only associated with borderline increased risk of death for CRC patients [9]. EGFR expression determined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) also have no correlation with the therapeutic response to EGFR antibody therapy nor prognosis in some reports [10], [11], [12], [13]. As for KRAS mutation, the results from the two clinical trials: Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 89803 (for stage III CRC patients) and Pan European Trial Adjuvant Colon Cancer (PETACC)-3 (for stage II and III CRC patients) all have demonstrated that KRAS mutation itself was not a major prognostic factor for patients treated with adjuvant 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy [14], [15].

In contrast, the association of MSI phenotype and survival in CRC patients has been more consistent. A meta-analysis of 32 studies including 7642 CRC patients demonstrated that patients with MSI-high tumors treated by adjuvant fluorouracil had prognostic advantage (HR = 0.65) [16]. This survival benefit was maintained when restricted to patients with stage II or III disease (HR = 0.75). The subsequent large clinical trial, PETACC-3, also confirmed that MSI phenotype is a strong prognostic factors for relapse-free and overall survival in stage II and III CRC [17].

About 85% of sporadic CRC have chromosomal instability with complex chromosomal alterations and the remaining 15% have MSI with frequent mutations in the short tandemly repeated nucleotide sequences (microsatellites) [2]. CRC with MSI is due to dysfunction of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system, which is caused by mutations or epigenetic methylations of the MMR genes. Lynch syndrome, also named hereditary nonpolyposis CRC, is the inherited prototype for MSI and most were resulted from MLH1 (MutL homolog 1), and MSH2 (MutS protein homolog 2) gene abnormality [18]. The standard method of MSI detection is genetic analysis by a panel of microsatellite markers. The Besthesda consensus defined five microsatellite loci (BAT25, BAT26, D5S346, D2S123, and D17S250), and instability at two or more loci (or >30% of loci) is considered to be MSI-high phenotype [19]. On the other hand, loss of MMR proteins, which include MLH1, PMS1 (Postmeiotic segregation increased 1), PMS2, MSH2, MSH3 and MSH6, determined by IHC stain also can have comparable sensitivity for detection of MSI and can provide additional functional status of individual proteins [20].

For patients with CRC, even in AJCC stage I or II (excluding pT1 tumors), a small fraction of patients remained suffering from local recurrence or distant metastatic disease after radical resection. Various studies have tried to identify the potential risk factors by analyzing important clinical, pathological, and molecular factors, but the results remained inconclusive [3], [4], [21], [22], [23]. In this study, we intend to examine all of the above mentioned biomarkers of colon cancers in a homogeneous cohort of stage I–II colon cancer patients to search for prognostic markers significantly associated with tumor recurrence and survival. These colon cancer patients all received complete radical resection by the same surgeon and none received adjuvant therapy.

Materials and methods

Patients

In this study, we have reviewed the surgical pathology reports of the colon cancer (adenocarcinoma) patients (rectal cancers were not included), who were all operated by one single surgeon (JSC) during 1995–2004 at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan. After patients with pT1 tumors were excluded, there were 549 colon cancer patients who had received a complete tumor resection (resection margins were all free). Among them, there were 296 patients with no lymph node or distant metastasis at the time of resection (stage I or II). During follow up, 38 of the 296 patients developed tumor recurrence or distant metastasis. Among the 296 patients, there were 112 patients with sigmoid colon cancers. Ninety one of these 112 patients had no tumor recurrence or distant metastasis during the follow up period. These 91 patients were belonged to “non-metastasis group”, and the remaining 21 patients were “metastasis group”. To increase the patient number of the metastasis group, all of the 38 colon cancer patients who developed tumor recurrence or distant metastasis were included in the “metastasis group” (21 were sigmoid colon cancer patients, 8 were ascending colon, 3 were transverse colon, and 6 were descending colon). Unstained formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue sections of these 2 groups of patients were prepared for genetic and IHC studies. The clinical and pathologic features, including age, gender, serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level, tumor size, main histological pattern (tubular versus mucinous), tumor grade [24], tumor stage (AJCC, 6th ed.) [25], numbers of dissected regional lymph nodes, and outcome were obtained from the medical records. There was no patient with family history of colon cancers in this study cohort. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Reviewing Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital prior to the study (96-1459B).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) study

Unstained FFEP tumor tissue sections of 3–4 um in thickness were used for IHC study. The source, clone, and dilution of antibodies were shown as below: p53 (DakoCytomation Denmark A/S, Glostrup, Denmark, clone DO-7, 1:50, antigen retrieval by heat denature), EGFR (DakoCytomation Denmark A/S, Glostrup, Denmark, clone H11, 1: 50, antigen retrieval by proteinase K for 8 min), MLH1 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, clone G168-15, 1:1, antigen retrieval by heat denature), and MSH2 (Calbiochem Inc., Darmstadt, Germany, clone FE11, 1: 25, antigen retrieval by heat denature). The detection was processed in the Discovery XT automated IHC/ISH slide staining system (Ventana Medical System, Inc. Tucson), using ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit (Ventana Medical System, Inc. Tucson), according to the manufacturer's instruction.

The IHC stains were read by two experience pathologists (SCH and SFH) independently and blinded to the clinical data. If there was any discordance, the slides would be reviewed again to reach a consensus. The p53 expression was subdivided as: “negative”, if the p53 stain was completely negative; “intermediate” for focal, weak, or with uneven staining pattern; “strong” for positive staining in more than 50% tumor cells in a diffuse and strong pattern. Tumors with “intermediate” expression were considered as having wild-type p53, and tumors with “negative” or “strong” expression were mutated p53, according to the published reports [26]. The EGFR expression was scored by the Hercept scale. Score “0” for negative stain or faint membrane or cytoplasmic staining <10%, “1” for weak staining >10%, “2” for moderate staining >10%, and “3” for strong staining >10%. Scores 2 and 3 were considered as having EGFR over-expression [27]. The intensity and extent of MLH1 and MSH2 expression were semi-quantitatively categorized by the Allred score [28]. The Allred score was a summary by adding proportion score and intensity score. The extent (proportion of tumor cells with positive stain) was scored from 0 (0%), 1 (<1%), 2 (1–10%), 3 (11–30%), 4 (31–60%), to 5 (>60%). The intensity of the stain was scored from 0 (no reactivity), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), to 3 (strong). Since the internal positive control cells (such as lymphocytes) had variable stain intensity for MLH1 and MSH2, we also have normalized the expression of tumor cells to the background cells when evaluating the intensities. The final score was obtained by summation of the scores of the extent and the intensity, and categorized as “negative” for 0, “intermediate” for 1–6, and “strong” for 7–8. Only the “strong” group was regarded as having “overexpression”. Tumors with negative expression were considered to have MSI.

KRAS gene mutation analysis

The tumor portions on FFPE tissue section were dissected for DNA extraction, which was performed with DEXPAT (TaKaRa Biomedical, Shiga, Japan), according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Only coding sequences of exon 2 and 3 of K-ras were amplified and subjected to direct sequencing. The PCR primers used were: E2F: 5′-GGT ACT GGT GGA GTA TTT GAT AG-3’; E2R: 5′-CAA AGA ATG GTC CTG CAC CAG-3’; E3F: 5′-GGA GCA GGA ACA ATG TCT TTT C-3’; E3R: 5′-GCA TGG CAT TAG CAA AGA CTC-3’. The PCR was performed according to the protocol published previously [29]. Forward and reverse sequencing reactions were performed using the same primers for PCR on an ABI3730 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). The sequences were determined by the Seqscape software (Applied Biosystems). The KRAS reference sequence is based on NM_004985 from the NCBI database. All mutations were verified on a second independent PCR product. In order to increase the sensitivity, HybProbe assay for analyzing KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations was also performed. The LightMix® Kit k-ras Mutation Codon 12/13 (TIB MOLBIOL Syntheselabor GmbH, Berlin, Germany) were used and performed according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical and survival analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 20; IBM, New York, NY, United States). The associations between metastasis, clinicopathological features, immunohistochemical reactivity, and KRAS gene mutation were evaluated by Pearson's χ2 test or Fisher exact tests. Variables with p value less than 0.10 in univariate analysis were re-assessed in a multivariate logistic model. Kaplan–Meier estimates and log-rank analyses were done for comparison of overall survival in different subgroups. The Cox proportional hazard regression model was undertaken to determine the consistency of prognostic effect. Two-sided p values were calculated and p < 0.05 was considered to be significant for all statistical analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

Among the 129 colon cancer patients, IHC stains were not successful in 9 patients' tumor tissue due to lack of residual tumor tissue in the sections or staining failure. Thus, only 120 colon cancer patients were included for this study. The follow up period ranged from 1.0 to 135.9 months (mean: 73.3 months). Except some patients who died of other diseases, all of the patients alive in the “non-meta” group were disease free for >5 years, and 16 patients have been disease free for >10 years. There were 33 patients (33/120, 27.5%) developed distant metastasis during the follow up period. The time to metastasis ranged from 4 to 83.9 months (median 15.9 months). Except for the 6 patients with no available data, the most common metastatic site was liver (17/27, 62.9%), followed by peritoneum (6/27, 22.2%), intraabdominal distant lymph nodes (6/27, 22.2%), lung (4/27, 14.8%), and ovary (1/27, 3.7%). Five patients had distant metastases in two or more organs at the same time. This study included 14 (11.7%) pT2 tumors, 50 (41.7%) pT3 tumors, and 56 (46.7%) pT4 tumors. When comparing the clinicopathological features between the two subgroups, only gender and serum CEA level had significant difference by univariate analysis [Table 1]. For the metastasis and non-metastatic groups, the female patients were 55.5% (18/33) versus 31.0% (27/87), respectively (p = 0.02). For patients with high serum CEA level (≧5 ng/ml), it was 51.5% (17/32) versus 32.2% (28/86), respectively (p = 0.04). The age distribution, tumor size, T stage, main histology patterns, tumor grades, and total harvested lymph node numbers all showed no significant differences. By multivariate analyses, the gender (p = 0.03) and high serum CEA level (p = 0.04) remained significant.

Table 1.

The clinicopathological characteristics of the 120 colon cancer patients.

| Variables | Patient no. (%) | Distant metastasis |

Univariate analysis p value | Multivariate analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive no. (%) | Negative no. (%) | p value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Age (yr) | 0.964 | |||||

| >60 | 84 (70.0) | 23 (69.7) | 61 (70.1) | |||

| ≦60 | 36 (30.0) | 10 (30.3) | 26 (29.9) | |||

| Gender | 0.018 | 0.035 | ||||

| Male | 75 (62.5) | 15 (45.5) | 60 (69.0) | 1 | ||

| Female | 45 (37.5) | 18 (54.5) | 27 (31.0) | 2.653 (1.070–6.579) | ||

| CEA (ng/ml)a | 0.041 | 0.041 | ||||

| <5 | 73 (61.9) | 15 (45.5) | 58 (66.7) | 1 | ||

| ≧5 | 45 (38.1) | 17 (51.5) | 28 (32.2) | 2.582 (1.040–6.410) | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.964 | |||||

| ≦5 | 84 (70.0) | 23 (69.7) | 61 (70.1) | |||

| >5 | 36 (30.0) | 10 (30.3) | 26 (29.9) | |||

| Tumor stage | 0.870 | |||||

| pT2-3 | 64 (53.4) | 18 (54.6) | 46 (52.9) | |||

| pT4 | 56 (46.6) | 15 (45.4) | 41 (47.1) | |||

| Main histology pattern | 1.000 | |||||

| Tubular | 113 (94.2) | 31 (93.9) | 82 (94.3) | |||

| Mucinous | 7 (5.8) | 2 (5.7) | 5 (5.7) | |||

| Tumor grade | 0.355 | |||||

| I/II | 110 (91.7) | 29 (87.9) | 81 (93.1) | |||

| III | 10 (8.3) | 4 (12.1) | 6 (6.9) | |||

| No. of dissected LN | 0.420 | |||||

| <12 | 47 (39.2) | 11 (33.3) | 36 (41.4) | |||

| ≧12 | 73 (60.8) | 22 (66.7) | 51 (58.6) | |||

| MLH1 over-expression | 0.002 | 0.003 | ||||

| Negative | 36 (30.0) | 3 (9.1) | 33 (37.9) | 1 | ||

| Positive | 84 (70.0) | 30 (90.9) | 54 (62.1) | 10.459 (2.266–48.264) | ||

| MSH2 overexpression | 0.327 | |||||

| Negative | 79 (65.8) | 24 (72.7) | 55 (63.2) | |||

| Positive | 41 (34.2) | 9 (27.3) | 32 (36.8) | |||

| p53 status | 0.233 | |||||

| Wild type | 28 (23.3) | 5 (15.1) | 23 (26.4) | |||

| Mutated | 92 (76.7) | 28 (84.9) | 64 (73.6) | |||

| EGFR overexpression | 0.766 | |||||

| Negative | 104 (86.7) | 28 (84.9) | 76 (87.4) | |||

| Positive | 16 (13.3) | 5 (15.1) | 11 (12.6) | |||

| KRAS mutation | 0.118 | |||||

| Absent | 104 (86.7) | 26 (78.8) | 78 (89.7) | |||

| Present | 16 (13.3) | 7 (21.2) | 9 (10.3) | |||

Abbreviations: CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; LN: regional lymph node.

Serum CEA data was unavailable in one patient for each subgroup, respectively.

Expression of MLH1, MSH2, p53 and EGFR

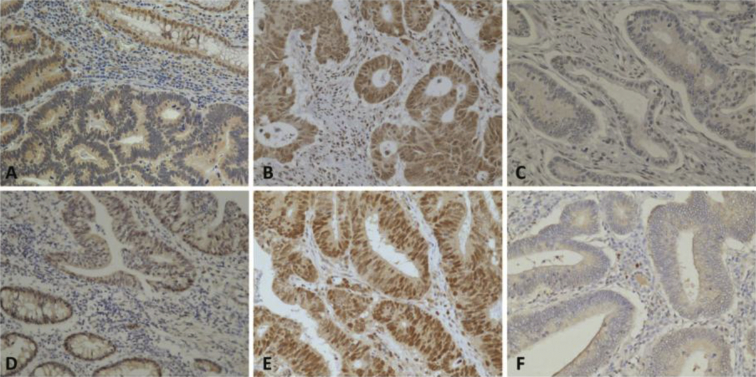

For MLH1 protein, none of the tumor had negative expression in the metastasis group, while 6 patients were negative in the non-metastatic group. In addition, up to 30 patients (30/33, 90.9%) in the metastatic group had overexpression of MLH1, but only 54 patients (54/87, 62.1%) had overexpression in the non-metastatic group. The difference was statistically significant by both univariate and multivariate analyses [Table 1]. For MSH2 protein, the metastasis group also had no tumor with negative expression, while 3 patients were negative in the non-metastatic group. MSH2 overexpression was found in 9 (27.3%) and 32 (36.8%) patients in the metastatic and the non-metastatic group, respectively. The differences were non-significant. The expression patterns of representative cases for MLH1 and MSH2 are shown in Fig. 1 p53 over-expression was found in 19 (57.6%) and 64 (73.5%) patients in the metastatic and the non-metastatic group, respectively. EGFR overexpression was recognized in 5 (15.1%) and 11 (12.6%) patients in the metastatic and the non-metastatic group, respectively. Alteration of the above two proteins all had no significant differences between the two study groups.

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical satin for MLH1 protein expression in the colon adenocarcinoma: (A) Intermediate expression (200×), (B) Overexpression (400×), (C) Negative expression (400×); for MSH2 protein expression: (D) Intermediate expression (200×), (E) Overexpression (400×), (F) Negative expression (400×).

KRAS gene mutation analysis

KRAS mutations of codon 12 and 13 were identified in 16 patients (13.3%), including 13 patients with mutations in codon 12 and 3 patients in codon 13. Seven patients were in the metastasis group and 9 in the non-metastasis group. The difference was non-significant (p = 0.12).

Risk assessment of metachronous distant metastasis

Univariate analysis of the clinicopathological features revealed that only female gender, high serum CEA level (≧5 ng/ml), and MLH1 overexpression were significantly associated with the metastasis group. The above three features remained significant by multivariate analysis. For female patients, the OR (odds ratio) was 2.653 and 95% CI (confidence interval) was 1.070–6.579 (p = 0.03). For high CEA level, the OR was 2.582 and 95% CI was 1.040–6.410 (p = 0.04). For MLH1 overexpression, the OR was 10.459 and 95% CI was 2.266–48.264 (p = 0.003) [Table 1].

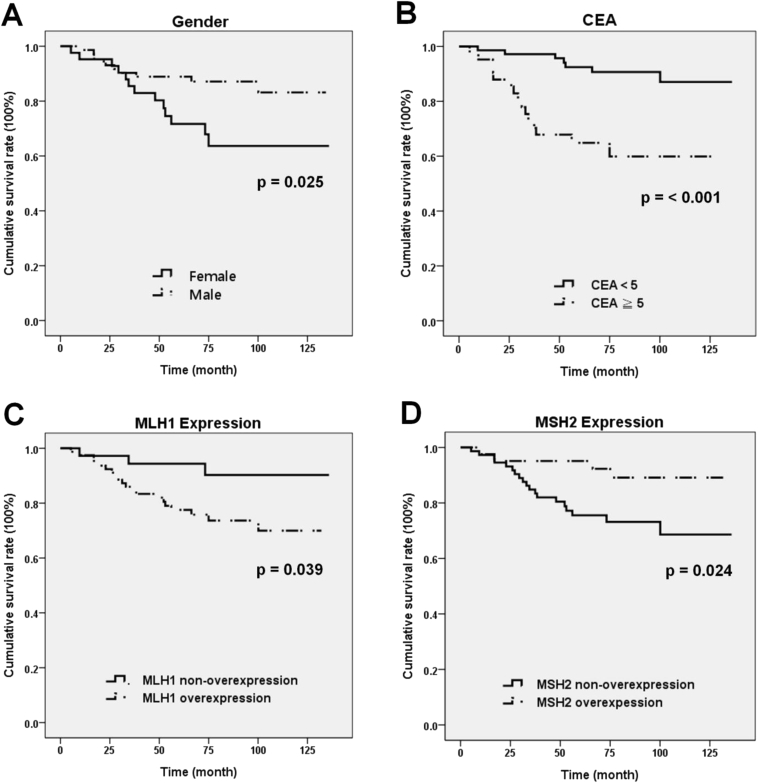

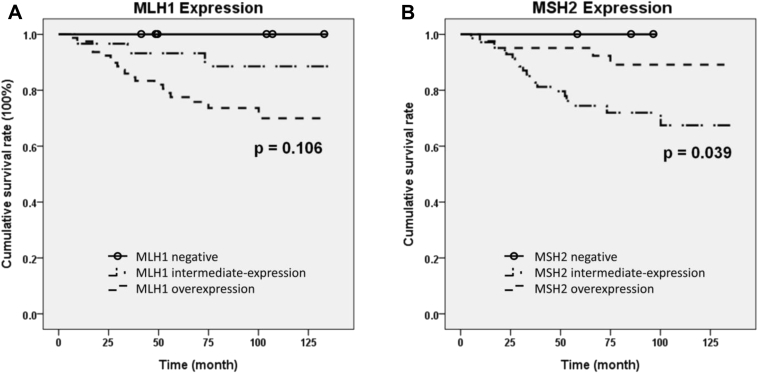

Survival analysis

The overall survival (OS) was analyzed, which was defined as the interval from the operation date till the date of death or last follow up. In the metastasis group, the mean following duration was 45.7 months (5.3–109 months). The median survival was 47.9 months. In the non-metastasis group, the mean follow-up time was 83.8 months (1.0–135.9 months). The median survival was not reached yet. As expected, the OS and 5-year–survival rate were both significantly different between the metastasis and non-metastasis group (p < 0.001). The variables associated with the OS and 5-year–survival rate were analyzed and shown in Table 2. The MLH1 and MSH2 expression were categorized as overexpression and non-overexpression. The latter was for tumors with negative or intermediate expression levels. Only gender, serum CEA level, and MLH1 and MSH2 overexpression were significantly associated with the 5 year survival and OS, respectively. The Cox proportional hazard regression model confirmed that female gender was also a poor prognostic factor for OS. The HR was 2.383 (95% CI 1.009–5.629) with a borderline p value (p = 0.048) [Fig. 2A]. High CEA level [p < 0.001, HR: 4.525, 95% CI 1.923–11.765] was an independent poor prognostic factor for OS [Fig. 2B]. MLH1 and MSH2 overexpression all showed significant association with OS, respectively. MLH1 overexpression was an indicator for shorter survival, when compared with patients with non-overexpression (p = 0.01, HR 6.173, 95% CI 1.425–26.316) [Fig. 2C]. In contrast, MSH2 overexpression was associated with longer survival (p = 0.02, HR 0.253, 95% CI 0.083–0.7) [Fig. 2D]. If the protein expression was divided in 3 levels (negative, intermediate and overexpression), and log-rank test was applied, MSH2 protein retained its statistic significance (p = 0.04) but MLH1 protein became non-significant (p = 0.11) [Fig. 3]. Other clinicopathological factors including p53 status, EGFR overexpression and KRAS mutation all showed no significant influence on survival.

Table 2.

The clinical variables associated with 5-year and overall survivals in the 120 colon cancer patients.

| Variables | Mean survival months (95% CI) | 5-year survival rate (%) | Univariate analysis p value | Multivariate analysis |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||||

| Metastasis | <0.001 | NA | |||

| Negative | NA | 100 | NA | ||

| Positive | 47.90a (28.62–67.18) | 38.2 | NA | ||

| Age (yr) | 0.985 | ||||

| >60 | 114.18 (100.76–127.53) | 82.7 | |||

| ≦60 | 114.01 (104.38–123.64) | 82.8 | |||

| Gender | 0.025 | 0.048 | |||

| Male | 119.36 (110.72–128.01) | 88.9 | 1 | ||

| Female | 102.67 (87.79–117.54) | 71.7 | 2.383 (1.009–5.629) | ||

| CEA (ng/ml) | <0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| <5 | 125.97 (118.94–132.99) | 92.4 | 1 | ||

| ≧5 | 91.50 (106.75–122.67) | 64.9 | 4.525 (1.923–11.765) | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.222 | ||||

| ≦5 | 105.12 (88.75–121.49) | 78.0 | |||

| >5 | 117.66 (108.92–126.39) | 84.6 | |||

| Tumor stage | 0.987 | ||||

| pT2-3 | 113.18 (102.35–124.02) | 84.5 | |||

| pT4 | 113.95 (102.25–125.65) | 81.0 | |||

| Histology | 0.861 | ||||

| Tubular | 114.21 (106.10–122.32) | 82.7 | |||

| Mucinous | 111.37 (77.66–145.12) | 83.3 | |||

| Differentiation | 0.710 | ||||

| I/II | 114.91 (106.87–112.96) | 83.3 | |||

| III | 103.78 (71.39–136.16) | 77.8 | |||

| Lymph node number | 0.379 | ||||

| <12 | 109.20 (95.31–123.08) | 76.5 | |||

| ≧12 | 116.48 (107.07–125.89) | 86.7 | |||

| MLH1 overexpression | 0.039 | 0.015 | |||

| Negative | 126.92 (117.13–136.72) | 94.4 | 1 | ||

| Positive | 105.90 (95.97–115.82) | 77.5 | 6.173 (1.425–26.316) | ||

| MSH2 overexpression | 0.024 | 0.016 | |||

| Negative | 107.51 (96.55–118.46) | 75.5 | 1 | ||

| Positive | 112.61 (113.58–131.65) | 95.1 | 0.253 (0.083–0.772) | ||

| P53 status | 0.210 | ||||

| Wild type | 111.51 (102.10–120.92) | 81.0 | |||

| Mutated | 122.43 (109.69–135.17) | 88.9 | |||

| EGFR overexpression | 0.974 | ||||

| Negative | 114.27 (105.78–122.75) | 83.3 | |||

| Positive | 113.35 (91.96–134.74) | 79.4 | |||

| KRAS mutation | 0.133 | ||||

| Absent | 116.31 (108.08–124.54) | 85.6 | |||

| Present | 92.58 (71.37–113.80) | 61.8 | |||

Abbreviation: NA: not applicable; CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; CI: confidence interval.

Median survival time.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier overall survival curve of the 120 colon adenocarcinoma patients according to different variables: (A) gender, (B) carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level, (C) MLH1 expression, and (D) MSH2 expression.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier overall survival curve of the 120 colon adenocarcinoma patients based on the three different expression levels of A: MLH1 protein, and B: MSH2 protein.

Discussion

In the present study, we have narrowed down the study cohort to only radically resected pN0 colon adenocarcinoma without chemotherapy. Detailed clinical, pathological, and various biomarkers were studied simultaneously. The tumor differentiation, pT4 stage, and inadequate lymph node dissections all showed no predictive or prognostic significance in this cohort, suggesting staging and histopathology are not useful prognostic factors for this group of early stage colon cancers. Only female gender, high CEA level (≧5 ng/ml), and MLH1 overexpression were significantly associated with metachronous distant metastasis. The above three factors were also significantly associated with shorter survival. In contrast, MSH2 overexpression emerged as an indicator of better survival with statistical significance. EGFR overexpression, p53 status, and KRAS mutation all were not significantly associated with outcome, which are similar to previous reports [7], [8].

It is uncertain why female gender had higher metastasis rate and shorter survival in this cohort. We do find some reports which described shorter survival in female patients with metastatic CRC. For example, in a recent trial, panitumumab added to FOLFOX significantly prolonged progression free survival in males but not in females with metastatic CRC [30]. In a meta-analysis, which included 345 females and 497 males CRC patients, they also found gender was a robust determinant of the chemotherapy delivery schedule and resulted in survival differences [31].

For CRC, measurement of serum CEA level is a widely accepted tumor marker for monitoring tumor response and recurrence. Our results is quite consistent with previous reports, which also found CEA to be a significant factor for predicting distant metastasis or survival in pathologically T1 or T2 CRC [21], [32], and stage II or III CRC, respectively [33]. Currently the American Society of Clinical Oncology did not recommend the use of preoperative CEA levels to determine whether patients with CRC were candidates for adjuvant therapy [5]. But the European Society for Medical Oncology has added high CEA level as a risk factor for a subgroup of stage II colorectal cancer [6].

For MSI phenotype, the current study demonstrated MLH1 overexpression was not only a predictor of metachronous distant metastasis, but also a poor prognostic factor. MSH2 overexpression was only significantly associated with better OS, but not predictive for distant metastasis. To our best knowledge, MMR protein overexpressions have never been reported to be significantly associated with the prognosis of CRC patients before. Currently, only deficiency of MMR protein in the colon cancers is considered to be clinically important. The pathologists do not pay attention to high or low expression of MMR protein in the tumors, since any unequivocally positivity is interpreted as positive of the MMR proteins. Actually, the IHC stain for those tumor with no MMR proteins deficiency does not always have (+) stain in near 100% of the tumor cells. So different intensities of the IHC stains for MMR proteins in different colon cancer tumor cells do exist [34].

In this study, either MLH1-negative or MSH2-negative patients all had longest OS [Fig. 3]. Since MLH1-negative or MSH2-negative tumors would result in MSI, our result is consistent with the reports that CRC with MSI-high tumors would have better survival [16], [17].

The overexpression of MMR protein logistically represents enhanced DNA repair capability and, therefore, should also confer a good prognosis, which could be the reason why patients with MSH2 overexpression had longer survival than those with non-overexpression in the current study. On the other hand, previous studies have disclosed that MLH1, PMS1, or PMS2 overexpression could increase spontaneous MLH1 gene mutation rate and inactivation of DNA mismatch repair [35], [36], [37]. This mechanism of inactivation of DNA mismatch repair genes is probably different from MSI caused by MMR protein deficiency, so it cannot confer the same favorable outcome. This could be the reason why MLH1 overexpression was a poor prognostic factor for distant metastasis and overall survival in the current report. Shcherbakova et al. have demonstrated that MLH1 protein overexpression in yeast could lead to formation of nonfunctional MMR complexes containing MLH1 homodimers [36]. Similar phenomenon also have been found in other MMR proteins. For examples, overexpression of MSH3 protein could reduced the MMR efficacy by increased formation of MSH2/MSH3 heterodimer at the expense of MSH2/MSH6 heterodimer [38]. Norris and his coworkers also have discovered prostatic cancer with high PMS2 protein levels had short disease-free period after radical prostatectomy [39], which is similar to our result for MLH1 overexpression.

The limitation of this study is its small patient population. Since this study series only focused on the stage I–II patients and had a very long follow up time, the study result should be still quite valuable. Although patients of the metastasis group were not limited to sigmoid colon cancer as in the non-metastasis group. It should have no significant impact. The AJCC staging for colon cancers does not need to include the location in colon, either.

In summary, we have demonstrated that high CEA level and overexpression of MLH1 were associated with shorter survival and overexpression of MSH2 were associated with longer survival in this study cohort. The reversed prognostic implications in the overexpression of MLH1 and MSH2 for stage I–II colon cancer patients has never been reported, which is worthy of further confirmation with larger patient numbers.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by grants from: National Health Research Institutes (NHRI MG-101-PP-04, NHRI MG-102-PP-04) to Shiu-Feng Huang.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

This study result has been presented as poster in: Gordon Research Conference: Mammalian DNA Repair, Dates: Feb. 8–13, 2015, Ventura, California, USA.

Contributor Information

Shiu-Feng Huang, Email: sfhuang@nhri.org.tw.

Jinn-Shiun Chen, Email: chenjs@adm.cgmh.org.tw.

References

- 1.Parkin D.M., Bray F., Ferlay J., Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham D., Atkin W., Lenz H.J., Lynch H.T., Minsky B., Nordlinger B. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2010;375:1030–1047. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gertler R., Rosenberg R., Schuster T., Friess H. Defining a high-risk subgroup with colon cancer stages I and II for possible adjuvant therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2992–2999. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mroczkowski P., Schmidt U., Sahm M., Gastinger I., Lippert H., Kube R. Prognostic factors assessed for 15,096 patients with colon cancer in stages I and II. World J Surg. 2012;36:1693–1698. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1531-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson A.B., 3rd, Schrag D., Somerfield M.R., Cohen A.M., Figueredo A.T., Flynn P.J. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3408–3419. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Cutsem E., Oliveira J. Primary colon cancer: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, adjuvant treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(Suppl. 4):49–50. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tejpar S., Bertagnolli M., Bosman F., Lenz H.J., Garraway L., Waldman F. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers in resected colon cancer: current status and future perspectives for integrating genomics into biomarker discovery. Oncologist. 2010;15:390–404. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walther A., Johnstone E., Swanton C., Midgley R., Tomlinson I., Kerr D. Genetic prognostic and predictive markers in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:489–499. doi: 10.1038/nrc2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munro A.J., Lain S., Lane D.P. P53 abnormalities and outcomes in colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:434–444. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinemann V., Stintzing S., Kirchner T., Boeck S., Jung A. Clinical relevance of EGFR- and KRAS-status in colorectal cancer patients treated with monoclonal antibodies directed against the EGFR. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicholson R.I., Gee J.M., Harper M.E. EGFR and cancer prognosis. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(Suppl. 4):S9–S15. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang C.W., Tsai H.L., Chen Y.T., Huang C.M., Ma C.J., Lu C.Y. The prognostic values of EGFR expression and KRAS mutation in patients with synchronous or metachronous metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:599. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ljuslinder I., Melin B., Henriksson M.L., Oberg A., Palmqvist R. Increased epidermal growth factor receptor expression at the invasive margin is a negative prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2031–2037. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roth A.D., Tejpar S., Delorenzi M., Yan P., Fiocca R., Klingbiel D. Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60-00 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:466–474. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogino S., Meyerhardt J.A., Irahara N., Niedzwiecki D., Hollis D., Saltz L.B. KRAS mutation in stage III colon cancer and clinical outcome following intergroup trial CALGB 89803. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7322–7329. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popat S., Hubner R., Houlston R.S. Systematic review of microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:609–618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roth A.D., Delorenzi M., Tejpar S., Yan P., Klingbiel D., Fiocca R. Integrated analysis of molecular and clinical prognostic factors in stage II/III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1635–1646. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boland C.R., Goel A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2073–2087. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.064. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boland C.R., Thibodeau S.N., Hamilton S.R., Sidransky D., Eshleman J.R., Burt R.W. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on microsatellite instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248–5257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shia J. Immunohistochemistry versus microsatellite instability testing for screening colorectal cancer patients at risk for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome. Part I. The utility of immunohistochemistry. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:293–300. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.080031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lou Z., Meng R.G., Zhang W., Yu E.D., Fu C.G. Preoperative carcinoembryonic antibody is predictive of distant metastasis in pathologically T1 colorectal cancer after radical surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:389–393. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nitsche U., Rosenberg R., Balmert A., Schuster T., Slotta-Huspenina J., Herrmann P. Integrative marker analysis allows risk assessment for metastasis in stage II colon cancer. Ann Surg. 2012;256:763–771. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318272de87. discussion 71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biffi R., Botteri E., Bertani E., Zampino M.G., Cenciarelli S., Luca F. Factors predicting worse prognosis in patients affected by pT3 N0 colon cancer: long-term results of a monocentric series of 137 radically resected patients in a 5-year period. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:207–215. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1563-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang H.C., Huang S.C., Chen J.S., Tang R., Changchien C.R., Chiang J.M. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in pT1 and pT2 rectal cancer: a single-institute experience in 943 patients and literature review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2477–2484. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene F.L., Page D.L., Fleming I.D., Fritz A.G., Balch C.M., Haller D.G., editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6th ed. Springer; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCluggage W.G., Soslow R.A., Gilks C.B. Patterns of p53 immunoreactivity in endometrial carcinomas: ‘all or nothing’ staining is of importance. Histopathology. 2011;59:786–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abd El All H.S., Mishriky A.M., Mohamed F.A. Epidermal growth factor receptor in colorectal carcinoma: correlation with clinico-pathological prognostic factors. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:170–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allred D.C., Harvey J.M., Berardo M., Clark G.M. Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer by immunohistochemical analysis. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:155–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu C.C., Hsu H.Y., Liu H.P., Chang J.W., Chen Y.T., Hsieh W.Y. Reversed mutation rates of KRAS and EGFR genes in adenocarcinoma of the lung in Taiwan and their implications. Cancer. 2008;113:3199–3208. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douillard J.Y., Siena S., Cassidy J., Tabernero J., Burkes R., Barugel M. Randomized, phase III trial of panitumumab with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) versus FOLFOX4 alone as first-line treatment in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: the PRIME study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4697–4705. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giacchetti S., Dugue P.A., Innominato P.F., Bjarnason G.A., Focan C., Garufi C. Sex moderates circadian chemotherapy effects on survival of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:3110–3116. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogata Y., Murakami H., Sasatomi T., Ishibashi N., Mori S., Ushijima M. Elevated preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen level may be an effective indicator for needing adjuvant chemotherapy after potentially curative resection of stage II colon cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:65–70. doi: 10.1002/jso.21161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim C.H., Huh J.W., Kim H.J., Lim S.W., Song S.Y., Kim H.R. Factors influencing oncological outcomes in patients who develop pulmonary metastases after curative resection of colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:459–464. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318246b08d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shia J., Stadler Z., Weiser M.R., Rentz M., Gonen M., Tang L.H. Immunohistochemical staining for DNA mismatch repair proteins in intestinal tract carcinoma: how reliable are biopsy samples? Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:447–454. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31820a091d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shcherbakova P.V., Kunkel T.A. Mutator phenotypes conferred by MLH1 overexpression and by heterozygosity for MLH1 mutations. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3177–3183. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shcherbakova P.V., Hall M.C., Lewis M.S., Bennett S.E., Martin K.J., Bushel P.R. Inactivation of DNA mismatch repair by increased expression of yeast MLH1. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:940–951. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.940-951.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibson S.L., Narayanan L., Hegan D.C., Buermeyer A.B., Liskay R.M., Glazer P.M. Overexpression of the DNA mismatch repair factor, PMS2, confers hypermutability and DNA damage tolerance. Cancer Lett. 2006;244:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marra G., Iaccarino I., Lettieri T., Roscilli G., Delmastro P., Jiricny J. Mismatch repair deficiency associated with overexpression of the MSH3 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8568–8573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norris A.M., Gentry M., Peehl D.M., D'Agostino R., Jr., Scarpinato K.D. The elevated expression of a mismatch repair protein is a predictor for biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2009;18:57–64. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]