Abstract

Background

Interleukin-10 secreting B-cells are a major subset of B-regulatory cells (B-regs), commonly recognized as CD19+/38hi/24hi/IL10+. They carry out immunomodulation by release of specific cytokines and/or cell-to-cell contact. We have generated B-regs in-vitro from donor adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD-MSC) and renal allograft recipient (RAR) peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) for potential cell therapy.

Material and methods

Mononuclear cells separated by density gradient centrifugation from 50 ml anti-coagulated blood of 15-RAR and respective donors were analysed for baseline B-regs using appropriate antibodies. Equal amount (20 × 106 cells/ml) of stimulator (irradiated at 7.45 Gy/min for 10 min) and responder (non-irradiated) cells were co-cultured with in-vitro generated AD-MSC (1 × 106 cells/ml) in proliferation medium containing lipopolysaccharide from E. coli K12 strain at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cells were harvested on day-7 and analyzed for viability, sterility, quantity, morphology and phenotyping. In-vitro generated B-reg levels were compared with baseline B-regs.

Results

In-vitro generated B-reg count increased to 16.75% from baseline count of 3.35%.

Conclusion

B-regs can be successfully generated in-vitro from donor AD-MSC and RAR PBMC for potential cell therapy.

Keywords: B-regulatory cells, Lipopolysaccharide E. coli, IL-10, Adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells, Peripheral blood mononuclear cells, Immunomodulation

Condensed abstract: Interleukin-10 secreting B-regs, recognized as CD19+/38hi/24hi/IL10+, cause immunomodulation by release of cytokines and/or cell-to-cell contact. We have generated B-regs in-vitro from donor adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD-MSC) and renal allograft recipient (RAR) peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). Mononuclear cells from blood of 15-RAR and respective donors were analyzed using antibodies and remaining cells were co-cultured with in-vitro generated AD-MSC in proliferation medium containing LPS-EK12 for 7 days. Mean B-reg count increased from 3.35% to 16.75%. Thus, B-regs can be successfully generated in-vitro from donor AD-MSC and RAR PBMC for potential cell therapy.

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

Autoimmune disorders require effective cell therapy since conventional chemotherapy is ineffective in ameliorating these diseases. Similarly solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients require life-long immunosuppression to prevent rejection. IL-10 secreting B-regulatory cells are known to have immunomodulatory role. We have generated in vitro, adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells and T-regulatory cells, and used them effectively to minimize immunosuppression in renal transplant patients. However we have not been able to sustain robust tolerance in all patients.

What this study adds to the field

The present study is unique experiment carried out using donor AD-MSC and transplant patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells to generate B-regs which will support the cell therapy armamentarium to induce robust tolerance, a Utopian dream of transplanters!

B-cells can dampen inflammation by interacting with effector T-cells and other cells. This suppressive or regulatory effect of B-cells is mediated by interleukin (IL)-10 production which inhibits T-helper (Th)1 and Th2 polarization, antigen presentation and pro-inflammatory cytokine production by myeloid cells. Absence of B-cells can cause or exacerbate autoimmune/inflammatory diseases like multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis, and introduction of these cells can ameliorate the disease [1], [2], [3], [4]. Thus the concept of ‘regulatory B-cell’ (B-reg) was born.

Although there are different markers for B-regs, they are commonly identified as CD19+/38hi/24hi/IL10+. Regardless of different markers used for their identification, majority of protective effects of B-regs are dependent on IL-10, a potent de-activator, which limits the intensity and duration of inflammatory responses [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. Thus IL-10 secretion is vital for identification of B-regs. B-reg stimulation can be achieved via Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) and TLR9-ligands using lipopolysaccharide (LPS), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, ionomycin and monensin [9], [10].

This was an Institutional Review Board approved prospective study to generate IL-10 secreting B-regs from co-culture of adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD-MSC) from 15 potential kidney donors and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of their potential renal allograft recipients (RAR). HCV, HIV, HBsAg seropositive patients/donors and those with major systemic illness, pregnancy and malignancy were excluded from study. Baseline B-regs were measured in all recipients and donors.

AD-MSC were further co-cultured with recipient peripheral blood mononuclear cells. These were divided into two parts, one as responder-PBMC and second part was irradiated to act as stimulator-PBMC. These were cultured for 7 days for in-vitro generation of B-regs.

Material and methods

Generation of AD-MSC

AD-MSC were generated as per our previous protocol [11]. Ten gram donor anterior abdominal pad of fat was resected under local anesthesia, collected in sterile 75 cm2 polystyrene tissue culture flasks containing 40 ml α-modified minimum essential medium (MEM), minced into tiny pieces and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h on shaker at 35–40 rotations per minute (rpm) in presence of collagenase-1 for digestion. Then they were centrifuged for 8 min at 780–800 rpm. The supernatant was discarded and cell-pellets were cultured in tissue cultur dishes containing α-MEM with growth factors, NaHCO3, glutamine, sodium pyruvate, albumin, antibiotics and antifungal agent, for 9 days at 37 °C in a humidified CO2 incubator. Media were replenished every other day and cells harvested after trypsinization on 9th day followed by re-suspension in Rosewell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) proliferation medium containing HEPES buffer, antibiotics and antifungal agent. Aliquots from this cell suspension were quantified and characterized by microscopy, counts, sterility, viability and flow cytometry.

PBMC isolation

PBMC separation was carried out as per our previous protocol [11]. On 9th day of in-vitro generation of AD-MSC, mononuclear cells were separated from 50 ml RAR Citrate Phosphate Dextrose-Adenine anti-coagulated blood using density gradient centrifugation.

B-reg generation

PBMC were evaluated by automated cell viability analyzer (Vi-Cell XR, Beckman Coulter, USA) and divided into two equal parts after quantifying their baseline B-regs. One part was kept as such to act as responder-PBMC (R-PBMC) and second part was irradiated for 10 min at 7.45 Gray/minute (Gy/min), to act as stimulator-PBMC (S-PBMC). Then AD-MSC, 1 × 106 cells/ml, and R-PBMC and S-PBMC each, 20 × 106 cells/ml were transferred in tissue-culture plate with 25–30 ml of proliferation medium [RPMI-1640 (Gibco Life Technologies, USA) containing HEPES buffer, albumin, antibiotics and antifungal agent. LPS-EK-12 (InvivoGen, USA), 100 ng/μL was added subsequently for activation. Tissue culture plates were then incubated at 37 °C in humidified incubator with 5% CO2 for 7 days. Media were replenished every other day. On 7th day, the cells were harvested using 1 N phosphate buffered saline (Hi Media, India).

An aliquot was tested for sterility (Bactec 6050, USA), quantified by automated cell viability analyzer, immunophenotype surface markers were studied by flow cytometry, trypan blue was also used to check viability, and morphology was examined by Leishman, and Hematoxylin–eosin stains.

Characterization of B-regs

Flow cytometric analysis was performed by Facscalibur (BD Biosciences, USA) as instructed in the user manual. Fluorescent tagged anti-human-CD19 [Peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-conjugated], anti-human-CD38 [Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated] and anti-human-CD24 [Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated] antibodies (BD Biosciences, USA) (10 μl each) were added to in-vitro generated cells, vortexed and incubated in dark for 15 min. The cells were thoroughly resuspended in 250 μl Cytofix/Cytoperm™ solution for 20 min at 4 °C for fixing and permeabilizing and then washed twice in 1 ml of 1X Perm/Wash™ solution following which the supernatant was removed. Subsequently anti-human-IL10 [Allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated] antibody (10 μl) was added for identifying IL-10 secreting cells. For each sample, 20,000 events were captured. CellQuestPro Software was used to analyze the data. An electronic gate was set for CD19+ CD38hi CD24hi IL10+ cells. Results were expressed as gated percentage.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. Data were expressed as mean ± SD for continuous variables. All data followed normal distribution. Paired t test was performed. p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

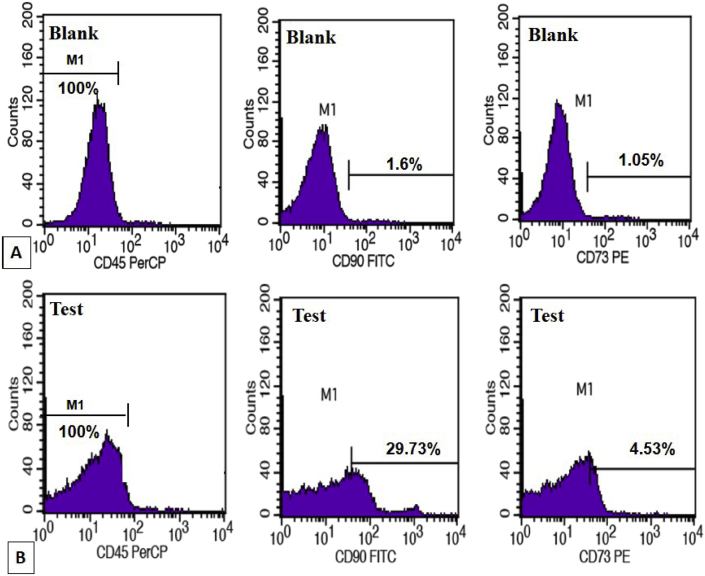

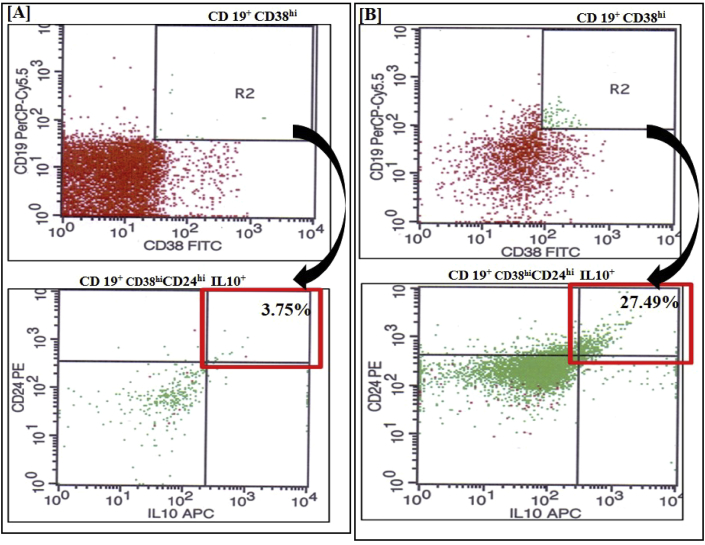

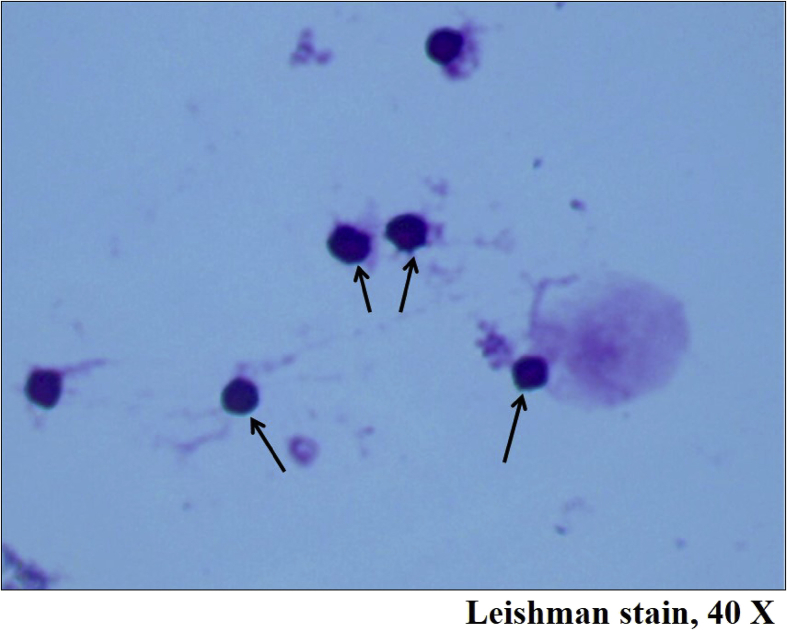

Mean AD-MSC count was 1.37 ± 0.47 × 106/ml with mean viability of 94.2 ± 2.7% and mean CD45−/CD90+ and CD45−/CD73+ constituting 11.02 ± 10.05% and 3.7 ± 7.61% respectively [Fig. 1]. No contamination was noted at any point during in-vitro generation. The results are shown in Table 1. Microscopically, on staining with hematoxylin and eosin, they appeared elongated with centrally placed basophilic nuclei and showed elongated cytoplasmic protrusions [Fig. 2]. Mean B-reg count of donors was 0.77 ± 0.67%. Mean PBMC count in RAR was 42.2 ± 13.43 × 106/ml with mean viability of 99.55 ± 0.29%. Mean baseline B-regs count in peripheral blood of RAR was 3.35 ± 1.32% and after in-vitro generation, it was 16.75 ± 6.25% with mean viability of 96.3 ± 2.8% [Fig. 3] achieved on day-7, with use of RPMI proliferation medium containing HEPES buffer, human albumin 20%, antibiotics and antifungal agent in presence of irradiated PBMC as stimulator cells and adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells. Microscopy revealed these cells to be round with large dark staining basophilic nuclei surrounded by thin rim of cytoplasm [Fig. 4].

Fig. 1.

Flow cytometry depicting immunophenotyping of adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells characterized by CD45− CD90+ CD73+. Representative histograms; (A) are blank readings depicting CD45− (100%), CD90+; (1.6%) and CD73+; (1.05%) and (B) are corresponding test readings showing CD45− (100%), CD90+; (29.73%) and CD73+; (4.53%). These show that there is rise in CD 90+ events in the test result to 29.73% from baseline levels of 1.6%. Similarly there is rise in baseline CD 73+ events in the test result to 4.53% from baseline levels of 1.05%. These results depict effective in vitro generation of mesenchymal stem cells.

Table 1.

Data on cell characterization of 15 donor–recipient pairs.

| Sr. no. | Donor AD-MSC |

RAR PBMC |

In vitro generated B-regs from RAR PBMC |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cells/ml (n × 106) | Viability (%) | CD45−/CD90+ | CD45−/CD73+ | Total cells/ml (n × 106) | Viability (%) | Baseline B-regs % CD19+/CD24+/38hi/IL10+) | Total cells/ml (n × 106) | Viability (%) | In vitro B-regs % (CD19+/CD24+/38hi/IL10+) | |

| 1 | 1.07 | 95.90 | 29.73 | 4.53 | 42.50 | 99.80 | 4.55 | 4.80 | 94.90 | 29.66 |

| 2 | 1.76 | 94.50 | 2.09 | 0.31 | 40.60 | 99.60 | 2.93 | 2.60 | 98.00 | 20.05 |

| 3 | 1.90 | 95.70 | 22.64 | 3.18 | 37.40 | 100.00 | 3.20 | 2.20 | 96.60 | 17.68 |

| 4 | 1.01 | 95.40 | 2.82 | 0.31 | 54.30 | 99.10 | 3.68 | 2.20 | 95.20 | 18.44 |

| 5 | 0.80 | 96.00 | 4.42 | 0.62 | 57.20 | 99.60 | 3.92 | 9.70 | 95.40 | 20.96 |

| 6 | 1.75 | 97.70 | 13.53 | 2.60 | 30.90 | 99.40 | 3.75 | 7.11 | 99.40 | 27.49 |

| 7 | 1.01 | 92.50 | 4.22 | 0.52 | 34.10 | 99.20 | 6.50 | 2.50 | 96.60 | 11.85 |

| 8 | 1.70 | 94.50 | 3.29 | 0.70 | 21.50 | 99.70 | 4.76 | 3.20 | 100.00 | 11.50 |

| 9 | 0.60 | 98.60 | 22.51 | 8.92 | 25.10 | 99.70 | 2.05 | 3.20 | 100.00 | 18.40 |

| 10 | 0.74 | 95.60 | 8.92 | 1.37 | 60.10 | 98.90 | 3.11 | 4.60 | 90.20 | 6.61 |

| 11 | 1.46 | 90.40 | 3.27 | 0.29 | 59.80 | 99.80 | 3.74 | 6.60 | 96.60 | 17.29 |

| 12 | 1.33 | 90.00 | 29.50 | 29.88 | 63.20 | 99.80 | 2.60 | 4.80 | 93.30 | 14.07 |

| 13 | 1.60 | 94.50 | 7.14 | 1.31 | 33.30 | 99.60 | 1.42 | 4.70 | 98.10 | 10.29 |

| 14 | 1.90 | 91.00 | 2.85 | 0.23 | 36.50 | 99.50 | 2.68 | 3.70 | 92.80 | 14.93 |

| 15 | 1.97 | 90.20 | 8.40 | 0.71 | 36.50 | 99.50 | 1.42 | 4.20 | 97.00 | 12.02 |

| 1.37 ± 0.47 | 94.17 ± 2.74 | 11.02 ± 10.05 | 3.70 ± 7.61 | 42.20 ± 13.43 | 99.55 ± 0.29 | 3.35 ± 1.32 | 4.41 ± 2.08 | 96.27 ± 2.76 | 16.75 ± 6.25 | |

Fig. 2.

Photomicrograph depicting in-vitro generated adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells appearing elongated with centrally placed basophilic nuclei and showed elongated cytoplasmic protrusions, Hematoxylin and Eosin stain, ×100.

Fig. 3.

Flow cytometry depicting B-regulatory cells (B-regs) characterized by CD19+ CD38hi CD24hi and IL10+. Representative dot plots of B-regs (A) in peripheral blood, (3.75%) and (B) after in-vitro generation, (27.49%). These plots show that there is rise in CD 19+ CD38hi CD24hi and IL10+ events after generation to 27.49% from baseline levels of 3.75% in peripheral blood depicting effective in vitro generation of B regs.

Fig. 4.

Photomicrograph depicting in-vitro generated B regulatory cells appearing round with large dark staining basophilic nuclei surrounded by thin rim of cytoplasm, adjacent large cells with pinkish cytoplasm are adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells, Leishman stain, 40×.

Statistical evaluation revealed mean difference of a pair 13.40, t value of 8.48 and for that p < 0.01 showed statistically significant difference. In-vitro generated B-regs were significantly more than those present in PBMC (p < 0.01).

Discussion

The present study was evolved with previous experience of in-vitro T-reg generation [11]. LPS-EK, the major structural component of the outer wall of Gram-negative bacteria, is a potent activator of the immune system. Large quantities of LPS induce overproduction of cytokines causing septic shock while sub-optimal doses induce tolerance [12]. We adopted the rationale to use donor derived AD-MSC along with irradiated PBMC instead of PMA, ionomycin or monensin. MSC provide the necessary cell-to-cell contact required for generation of T-regs [13]. Hence we decided to use MSC for B-reg generation also. IL-10 also known as cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor (CSIF), is the charter member of the IL-10 family secreted by activated hematopoietic and many other cells [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. IL-10 promotes phagocytic uptake and Th2 responses but suppresses antigen presentation and Th1 pro-inflammatory responses. It is critical in controlling viral infections as well as allergic and autoimmune inflammation [19], [20], [21].

For flow-cytometric analysis, we selected three other cell surface markers apart from the cytoplasmic IL-10; namely CD19, CD38, and CD24. CD19 is a 95 kD type-I transmembrane glycoprotein expressed on B-cells during all stages of maturation and differentiation, (except plasma cells) and follicular dendritic cells. It binds to CD21, CD81 and/or MHC-II and functions as a signal transduction molecule that regulates B-cell development, activation, proliferation and differentiation. CD38 is a 45 kD type II single-chain transmembrane glycoprotein expressed on surface of thymocytes, activated T-cells and terminally differentiated B-cells (plasma cells), monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells and some epithelial cells. It binds to CD31 and acts as a signal transduction ectoenzyme. CD24 is a 35–45 kD two chain-glycoprotein present on surface of B-cells and granulocytes which binds to CD62P. It regulates B-cell proliferation and maturation.

B-cells were believed predominantly to play an effector role in producing antigen-specific antibodies, inducing optimal T-cell activation and antigen presentation to CD4+ T-cells. B-cells are also central to the pathogenesis of many autoimmune diseases through the secretion of autoantibodies or antigen presentation. In recent years, B-cells have been demonstrated to down-regulate inflammatory reactions and induce tolerance by production of IL-10 and/or TGF-β and interacting with pathogenic T-cells to inhibit harmful immune responses. The term “regulatory B-cells” was introduced by Mizoguchi et al. [2] B-regs had been shown to ameliorate murine allergic and autoimmune diseases like contact hypersensitivity, asthma, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, lupus, and collagen induced arthritis.

The IL-10 producing B-cell subset characterized in humans normally represents 1% to 3% of spleen B-cells and <1% of peripheral blood B-cells [22]. Our study also confirms this observation with approximate count of 0.8%. Our patients with CRF had mean baseline B-regs of 3.35%. This could be due to their compensatory regulatory activity due to immune injury on the body. Human B-regs are enriched in both transitional (CD24hiCD38hi) and memory (CD24hiCD27+) B-cells [22], [23]. Human CD19+CD25hiCD86hiCD1dhi B-regs could suppress the proliferation of CD4+ T-cells and enhance Foxp3 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) expression in T-regs by producing IL-10 and TGF-β. [23]

Due to their ability to interact with a vast array of other immune subsets, and inhibit pro-inflammatory signals, B-regs could be used as a novel therapy in autoimmune diseases.

This study shows that B-regs can be successfully generated in-vitro by co-culture of donor AD-MSC and recipient PBMC for potential cell therapy for autoimmunity and alloimmunity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Wolf S.D., Dittel B.N., Hardardottir F., Janeway C.A., Jr. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis induction in genetically B-cell deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2271–2278. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizoguchi A., Mizoguchi E., Takedatsu H., Blumberg R.S., Bhan A.K. Chronic intestinal inflammatory condition generates IL-10-producing regulatory B-cell subset characterized by CD1d up regulation. Immunity. 2002;16:219–230. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mauri C., Gray D., Mushtaq N., Londei M. Prevention of arthritis by interleukin 10 producing B cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:489–501. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fillatreau S., Sweenie C.H., McGeachy M.J., Gray D., Anderton S.M. B cells regulate autoimmunity by provision of IL-10. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:944–950. doi: 10.1038/ni833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang X., Yang J., Chu Y., Wang J., Guan M., Zhu X. T follicular helper cells mediate expansion of regulatory B cells via IL-21 in Lupus-Prone MRL/lpr mice. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsushita T., Yanaba K., Bouaziz J.D., Fujimoto M., Tedder T.F. Regulatory B-cells inhibit EAE initiation in mice while other B-cells promote disease progression. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3420–3430. doi: 10.1172/JCI36030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blair P.A., Noreña L.Y., Flores-Borja F., Rawlings D.J., Isenberg D.A., Ehrenstein M.R. CD19+CD24hiCD38hi B-cells exhibit regulatory capacity in healthy individuals but are functionally impaired in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Immunity. 2010;32:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrne S.N., Halliday G.M. B-cells activated in lymph nodes in response to ultraviolet irradiation or by interleukin-10 inhibit dendritic cell induction of immunity. J Investig Dermatol F. 2005;124:570–578. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miles K., Heaney J., Sibinska Z., Salter D., Savill J., Gray D. A tolerogenic role for Toll-like receptor 9 is revealed by B-cell interaction with DNA complexes expressed on apoptotic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:887–892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109173109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsushita T., Tedder T.F. Identifying regulatory B cells (B10) that produced IL-10. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;677:99–111. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-869-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trivedi H.L., Vanikar A.V., Thakker U., Firoze A., Dave S.D., Patel C.N. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells combined with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation synthesize insulin. Transplant Proc. 2008;404:1135–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.03.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujihara M., Muroi M., Tanamoto K., Suzuki T., Azuma H., Ikeda H. Molecular mechanisms of macrophage activation and deactivation by lipopolysaccharide: roles of the receptor complex. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;1002:171–194. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanikar A.V., Trivedi H.L., Chooramani S.G., Kumar A., Dave S.D. Pre-transplant co-infusion of donor-adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells may help in achieving tolerance in living donor renal transplantation. Ren Fail. 2014;36:457–460. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2013.868295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Garra A., Vieira P. T(H)1 cells control themselves by producing interleukin-10. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:425–428. doi: 10.1038/nri2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pestka S., Krause C.D., Sarkar D., Walter M.R., Shi Y., Fisher P.B. Interleukin-10 and related cytokines and receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:929–979. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathurin P., Xiong S., Kharbanda K.K., Veal N., Miyahara T., Motomura K. IL-10 receptor and coreceptor expression in quiescent and activated hepatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G981–990. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00293.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grewe M., Gyufko K., Krutmann J. Interleukin-10 production by cultured human keratinocytes: regulation by ultraviolet B and ultraviolet A1 radiation. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:3–6. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12613446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szony B.J., Bata-Csörgo Z., Bártfai G., Kemény L., Dobozy A., Kovács L. Interleukin-10 receptors are expressed by basement membrane anchored, alpha(6) integrin(+) cytotrophoblast cells in early human placenta. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5:1059–1065. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.11.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzgerald D.C., Zhang G.X., El-Behi M., Fonseca-Kelly Z., Li H., Yu S. Suppression of autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system by interleukin 10 secreted by interleukin 27-stimulated T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1372–1379. doi: 10.1038/ni1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu K., Bi Y., Sun K., Wang C. IL-10-producing type 1 regulatory T cells and allergy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2007;4:269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blackburn S.D., Wherry E. IL-10, T cell exhaustion and viral persistence. J Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwata Y., Matsushita T., Horikawa M., Dilillo D.J., Yanaba K., Venturi G.M. Characterization of a rare IL-10-competent B-cell subset in humans that parallels mouse regulatory B10 cells. Blood. 2011;117:530–541. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessel A., Haj T., Peri R., Snir A., Melamed D., Sabo E. Human CD19+CD25high B regulatory cells suppress proliferation of CD4+ T cells and enhance Foxp3 and CTLA-4 expression in T-regulatory cells. Autoimm Re. 2012;11:670–677. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]