Abstract

The acquisition of self-perpetuating, immunological tolerance specific for graft alloantigens has long been described as the “holy grail” of clinical transplantation. By removing the need for life-long immunosuppression following engraftment, the adverse consequences of immunosuppressive regimens, including chronic infections and malignancy, may be avoided. Furthermore, autoimmune diseases and allergy are, by definition, driven by aberrant immunological responses to ordinarily innocuous antigens. The re-establishment of permanent tolerance towards instigating antigens may, therefore, provide a cure to these common diseases. Whilst various cell types exhibiting a tolerogenic phenotype have been proposed for such a task, tolerogenic dendritic cells (tol-DCs) are exquisitely adapted for antigen presentation and interact with many facets of the immune system: as such, they are attractive candidates for use in strategies for immune intervention. We review here our current understanding of tol-DC mediated induction and maintenance of immunological tolerance. Additionally, we discuss recent in vitro findings from animal models and clinical trials of tol-DC immunotherapy in the setting of transplantation, autoimmunity and allergy which highlight their promising therapeutic potential, and speculate how tol-DC therapy may be developed in the future.

Keywords: Dendritic cell, Tolerance, Allograft rejection, Autoimmunity, Regulatory T cell, Immunotherapy

Immunologic tolerance is the specific absence of a destructive immune response to a specific antigen. Due to the inherently random nature of somatic recombination of T cell receptor (TCR) genes within developing thymocytes, a small population of mature thymocytes with self-reactive specificities persists following negative selection within the thymus. Mechanisms of self-tolerance, therefore, allow control of these hazardous autoreactive lymphocytes. The deliberate induction of tolerance to specific antigens may have important implications across a number of fields. Recently, exciting progress has been made in the use of tol-DCs in transplantation, autoimmunity and allergy. This review will describe the mechanisms of action of these tol-DCs and outline their use in the pre-clinical and clinical setting.

Mechanisms of DC-mediated tolerance

Since their discovery by Steinman and Cohn over 40 years ago, DCs have been predominantly viewed as immunogenic leukocytes, responsible for the coordination of powerful, antigen-specific immune responses distant from the site of antigen acquisition. In more recent history, these professional antigen presenting cells (APCs) have been shown to play a critical role in both the induction and maintenance of immunological tolerance. The extraordinary plasticity of phenotypes DCs can display, in addition to numerous DC subsets that have been described, are the predominant factors underlying their ability to produce apparently diametrically-opposed effects on the immune system.

The detection of pathogen- or damage-associated signatures by DCs during classical immune responses triggers substantial upregulation of gene products required for effective antigen presentation and effector T cell (Teff) activation, including MHC Class II, CD80/86 and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Such changes are required to fulfil the three-stage activation of naïve Teffs: TCR engagement of cognate peptide-MHC (signal 1), ligation of costimulatory receptors (CD28) by costimulatory molecules (CD80 and CD86) (signal 2) and ligation of receptors with T cell stimulating cytokines (signal 3).

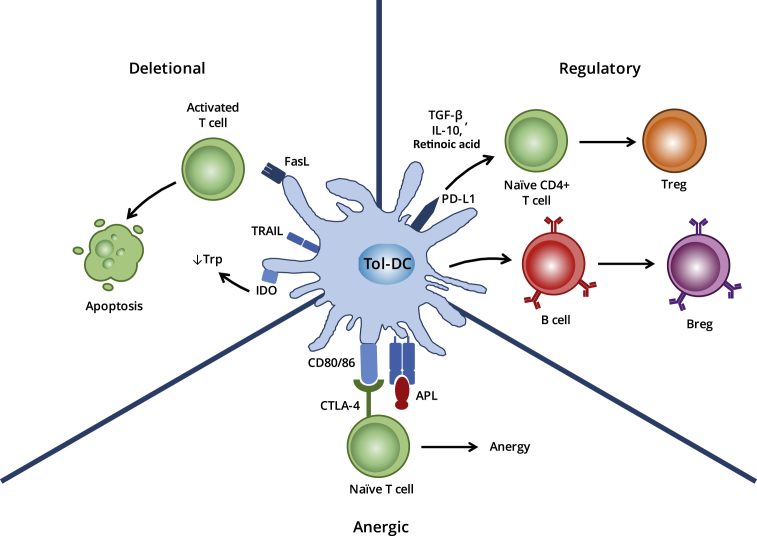

By contrast, tol-DCs are highly effective in antigen uptake, processing and presentation, but do not provide naïve T cells with the necessary costimulatory signals (signal 2) required for Teff activation and clonal proliferation on engagement [Fig. 1]. In addition, whilst tol-DCs secrete only minimal amounts of interleukin (IL)-12, a critical component of signal 3, they produce large amounts of anti-inflammatory IL-10 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β. Tol-DCs may actively induce and maintain tolerance through regulatory or deletional mechanisms. The discovery of autoimmune regulator (AIRE)-dependent autoreactive T cell deletion within secondary lymphoid tissues, in addition to the generation of natural T regulatory (Treg) cells within the thymus has demonstrated a clear overlap between central and peripheral tolerance mechanisms [1]. A number of additional factors may contribute to or augment the ability of tol-DCs to establish tolerance.

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of action of tol-DCs. The inhibition of T cell activation by tol-DCs has been attributed to various mechanisms that need not be mutually exclusive. These include Fas-FasL-mediated cell death of responding T cells, their functional paralysis through the induction of anergy or the polarisation of naïve T cells towards a regulatory phenotype through the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β.

Maturation status

Tol-DCs display an immature phenotype under steady state conditions and constitutively migrate throughout the periphery and lymphatic system, presenting self-antigen in the absence of costimulatory molecules. Immature, migratory DCs loaded with tissue antigens, such as those found in skin, are more effective at inducing antigen-specific FoxP3+ Treg cell populations than lymphoid resident DCs in vivo. This strongly suggests a role for migratory, immature DCs in promoting peripheral tolerance in the steady state [2].

Previous experiments have demonstrated that the maintenance of cells in an immature state, due to absence of maturation stimuli is associated with tolerance via induction of T cell deletion, anergy and polarisation towards a regulatory phenotype. The decision to polarize towards an immunogenic, or conversely, a tolerogenic phenotype may also be driven by whether DCs engulf necrotic or apoptotic cells. Upon engulfment of necrotic, stressed or virally infected cells, DCs become activated to stimulate both CD4+ and CD8+ Teff responses [3]. In contrast, engulfment of healthy or apoptotic cells polarizes DCs to a tolerogenic state, resulting in the promotion of T cell anergy and death. Apoptotic cells, therefore, appear to be an insufficient stimulus for full DC maturation. Interestingly, immature DCs appear specialised for the uptake of apoptotic cells, and in doing so, acquire a tolerogenic phenotype that is resistant to maturation. Uptake of apoptotic DCs by immature DCs results in the generation of tol-DCs that have the potential to induce FoxP3+ Treg cells via TGF-β1 secretion [4].

Interestingly, recent studies have demonstrated that traditionally-matured DCs are capable of inducing and expanding Treg cells [5]. It is possible, therefore, that the maturation status of DCs is not an absolute determinant of immunogenic/regulatory phenotypes.

Anergic tolerance

Whilst true T cell anergy can be achieved in vitro simply in the absence of co-stimulation, more active suppressing mechanisms are required for T cell anergy in vivo. Tol-DCs actively induce anergy among T cells via binding of CTLA-4 on activated T cells [Fig. 1], which functions as a potent inhibitor of T cell activation, via a suppressive effect on IL-2 production, IL-2R upregulation and cell cycle progression [6]. DC-induced anergic T cells perpetuate ongoing tolerance through the acquisition of suppressor activity, largely due to CTLA-4 upregulation [7]. In this way, a single tolerogenic DC may trigger a cascade of events, culminating in a significantly amplified pro-tolerogenic signal, with potential implications in the future development of therapeutic strategies.

Deletional tolerance

In order to maintain immunological homoeostasis and prevent deleterious autoreactive responses, tol-DCs assist with the active removal of potentially autoreactive, naïve T cells from the body, both within the thymus and in the peripheral tissues. Certain subclasses of splenic DC induce extensive T cell apoptosis in a manner dependent on an interaction between DC Fas ligand (FasL) and Fas expressed by the target lymphocyte [Fig. 1] [8]. Ex vivo generated 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VitD3)-cultured tol-DCs also demonstrate the ability to induce autoreactive T cell apoptosis in culture [9]. A number of mechanisms may underlie tol-DC induced apoptosis, including interactions between FasL and Fas [8], [10], [11], tryptophan catabolism through indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) expression [12], [13], [14] and TRAIL interactions with TRAIL receptors [15].

More recently, ligation of Fas on tol-DCs themselves has been shown to significantly improve their ability to inhibit CD4+ T cell proliferation and enhance IL-10 secretion [16]. Whilst this has been demonstrated in co-cultures between FasL+ activated T cells and Fas+ regulatory DCs, it is conceivable that FasL presented by regulatory DCs may also promote enhanced tolerogenic phenotypes in neighbouring DCs, acting via a feed-forward mechanism.

In addition to Teffs, long lived memory T cells represent a further threat to the induction and maintenance of tolerance [17], [18], [19]. However, DCs presenting cognate antigen to such lymphocytes are capable of triggering substantial deletion and inactivation of CD4 and CD8 memory T cells, inhibiting subsequent recall responses [20], [21], [22], [23]. Given that memory lymphocyte responses are frequently resistant to endogenous and pharmacological tolerance-inducing mechanisms to which naïve T cells are susceptible, this may prove to be particularly useful for the treatment of disease states perpetuated by memory T cell activation, such as Type I diabetes or transplantation [24]. Furthermore, memory T cell populations are poorly controlled by immunosuppressant medication [25]. The difficulty of overcoming memory T cell responses is demonstrated in transplantation studies in which Tregs are poorly equipped to suppress memory T cell proliferation and cytokine production [26] and those capable of suppressing naïve T cell mediated grafts fail to suppress memory T cell mediated rejection [27]. The ability for tol-DCs to induce deletional tolerance in naïve and memory lymphocyte populations may, therefore, permit more robust tolerance than alternative methods.

Regulatory tolerance

As the major bridge between the non-specific innate response and highly-targeted adaptive response, the key role of DCs is to prime naïve T cells to generate a range of effector lymphocytes. In the presence of tolerogenic signals, including TGF-β and retinoic acid, and the absence of strong costimulation, presentation of peptide-MHC complexes by DCs to naïve CD4+FoxP3− T cells may result in their differentiation to induced Tregs (iTregs) [Fig. 1]. This subset functions to maintain tolerance to innocuous foreign antigens. It appears that tissue specific subsets of DCs, such as CD8α+ DEC-205+ splenic DCs and CD103+ intestinal DCs in the mouse, are highly specialised for this purpose [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]. Furthermore, mature DCs exhibit the ability to expand ordinarily non-proliferative natural Tregs (nTregs), a key population maintaining tolerance to self-antigens, in a CD80/86 and IL-2 dependent manner [5], [33].

IL-10 plays a significant role in the generation of iTregs through conditioning CD4+ T cells to become unresponsive to antigens and express a suppressive phenotype [34], [35]. DCs differentiated in the presence of IL-10 secrete significant quantities of IL-10 and minimal IL-12 on activation. In both in vitro and in vivo studies, this has been shown to induce the differentiation of naïve T cells to a regulatory phenotype [36], [37].

In addition to IL-10, presentation of antigen by DC in the presence of TGF-β, a regulatory polypeptide cytokine, promotes differentiation of naïve T cells into Tregs. Transgenic murine studies of a DC-selective loss of TGF-β indicate that DCs are an important source of TGF-β in vivo, as transgenic animals suffer severe autoimmunity and colitis, indicative of poor Treg induction [38]. Furthermore, DC-driven differentiation of FoxP3− precursors into FoxP3+ Tregs in vitro is blocked with the addition of neutralizing antibodies to TGF-β [30].

Tol-DCs may also polarize T cells towards a regulatory phenotype through the surface expression of the immunoregulatory molecule PD-L1, which, when blocked, redirects T cells to an immunogenic, interferon (IFN)-γ secreting phenotype [39]. Some evidence suggests that the ligation of surface PD-L1 triggers IL-10 production, which consequently polarizes naïve T cells to Tregs [40].

Although previously viewed as a one-way flow of information (from dendritic cell to naïve T cell), the DC phenotype and function also critically depend on Tregs signals. Indeed, early in vitro studies of CD4+CD25+ Treg demonstrated their ability to downregulate CD80 and CD86 co-stimulatory molecules, via both transcriptional and non-transcriptional mechanisms [41], resulting in poor subsequent T cell proliferative responses [42]. Further, production of IL-10 by Tregs has been shown to induce tol-DCs, which are themselves capable of secreting TGF-β, IL-10 and IL-27 and generating regulatory cells [43].

In addition to Treg induction, in vitro evidence suggests that dexamethasone and vitD3-induced tol-DCs promote the induction of regulatory B cells [Fig. 1] [44], [45] which function to suppress inflammatory lymphocyte differentiation [46], promote the differentiation of FoxP3+ Tregs [47], [48] and attenuate neonatal DC immunogenicity [49].

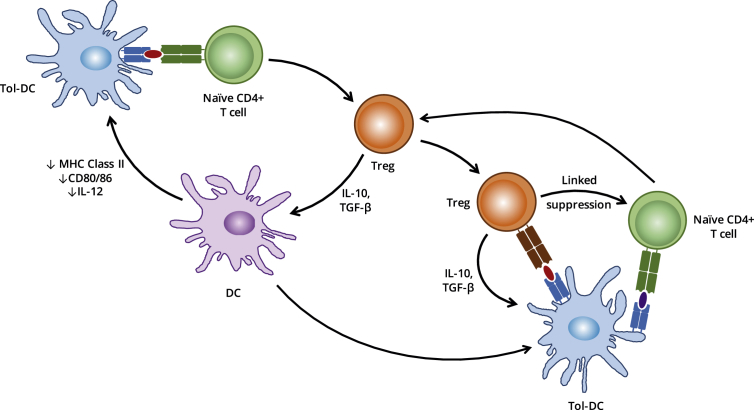

Infectious tolerance

The naturally-occurring phenomenon of infectious tolerance is one of the key, theoretical benefits to the use of cellular therapy in establishing long term tolerance to self- and alloantigens in the clinic. Infectious tolerance may be defined as the transmission of a regulatory phenotype from one lymphocyte population (Tregs) to another, either directly [50], [51], [52] or via an intermediate APC [Fig. 2] [53], [54]. As such, a single tolerising signal, such as an antigen-pulsed tol-DC, may be sufficient to establish self-perpetuating, long-term tolerance towards a specific antigen in vivo, through the induction of Treg populations that may propagate further Tregs in a chain reaction-style process.

Fig. 2.

The cycle of infections tolerance. Infectious tolerance, mediated through the activity of Treg cells, is inherently self-sustaining: presentation of antigen by DCs in a suboptimal manner promotes the polarisation of naïve T cells towards an iTreg phenotype capable of reinforcing the tolerogenicity of the DCs through secretion of TGF-β and IL-10. These cytokines may also act directly on naïve T cells recognising antigen de novo, thereby recruiting them to the pool of iTreg cells.

Tolerogenic dendritic cells in clinical transplantation

Following transplantation of allogeneic tissue, it is currently necessary for recipients to receive long term immunosuppression in order to prevent or limit powerful anti-donor immune responses and subsequent organ rejection. A range of immunosuppressive agents, with varying modes of action, have been utilised in preventing graft rejection. A significant consequence of the use of such drugs is increased tumour incidence and predisposition to a variety of opportunistic infections. Maintenance immunosuppression is ineffective at preventing chronic rejection, occurring months or years after tissue engraftment. These drawbacks, in combination with the high costs associated with prolonged maintenance immunosuppression, mean that the discovery of entirely efficacious and single dose treatments to induce lifelong allograft tolerance is the primary objective in transplant research. The use of tol-DCs for induction of transplantation tolerance is an attractive strategy, as it permits presentation of a few allogeneic antigens which can facilitate tolerance to the entire graft via infectious tolerance.

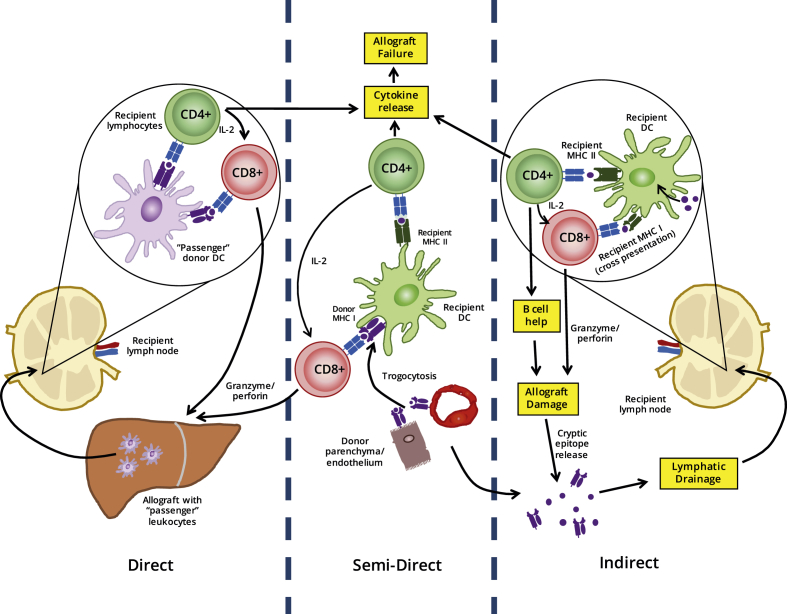

The role of DCs in transplant rejection

DCs act as the primary initiator of rejection responses in transplantation. Allogeneic DCs present allo-peptide-MHC molecules, accompanied by costimulation and appropriate cytokines, to recipient T cells, resulting in T cell clonal expansion and effector function. As developing recipient thymocytes are not exposed to such peptide-MHC complexes during early repertoire selection, the T cell pool has never been rendered tolerant to such antigens, meaning approximately 10% of the total repertoire [55] may be activated on encountering donor APCs. DCs transferred within allografts, so called “passenger leukocytes”, are therefore considered to be a major cause of acute graft rejection across MHC discordant barriers. This series of events is termed the direct pathway of alloantigen recognition [Fig. 3]. The observation of continued rejection even following donor DC ablation suggests that other processes also contribute to graft failure. Glimcher et al. demonstrated that MHC Class II-deficient skin grafts from knock out mice are rejected rapidly in normal recipients depleted of CD8+ T cells. Depletion of the remaining CD4+ T cells in recipients revealed these cells to be involved or necessary for this rejection. Since the only mechanism by which CD4+ T cells could react to the graft is via presentation of donor antigens by MHC Class II expressed by recipient APCs, another route of alloantigen recognition must occur alongside the direct pathway [56]. Termed indirect alloantigen recognition, recipient DCs acquire alloantigen from engrafted allogeneic tissues, processing and presenting peptides derived from such antigens in the context of self-MHC molecules [Fig. 3]. Whilst the T cell repertoire reactive to allopeptide-self-MHC molecules will be substantially lower than in the direct pathway, the self-MHC restricted clonal T cell response is still sufficient to trigger graft tissue destruction. Due to the time required for recipient DC migration, antigen acquisition, processing and presentation, the indirect pathway of alloantigen recognition is considered a significant cause of chronic allograft vasculopathy. Importantly, unlike passenger leukocytes, recipient DC populations are constantly replenished, preventing indirect pathway alloresponses declining over time. More recently, it has become apparent that a third pathway of allorecognition exists: intact donor MHC molecules may be transferred onto the surface of recipient APCs, in a process known as ‘cross-dressing’, and subsequently be presented to naïve recipient lymphocytes. In this way, a donor MHC Class I molecule presented by a single APC may activate CD8+ T cells via this so called “semi-direct” pathway, as well as activate CD4+ T cells via antigen processing and presentation by recipient MHC Class II molecules [Fig. 3] [55], [57].

Fig. 3.

The role of DCs in the initiation of allograft rejection. Alloantigens expressed by the graft may be presented whole to the recipient T cell repertoire by DCs carried over in the graft as ‘passenger leukocytes’, a process known as the direct pathway. The recipient's own DCs may passively acquire foreign MHC molecules on their surface while patrolling the graft through the process of trogocytosis and induce allo-responses via the semi-direct pathway. In the indirect pathway, these same recipient DCs take up alloantigens shed by the graft and dying cells of donor origin and present them as processed peptides in a classical MHC-restricted manner.

Whilst DCs clearly pose a significant threat to the survival of allografts, they may also hold the key to overcoming immunological rejection altogether. The very attributes that make DCs potent stimulators of transplant rejection may ultimately be harnessed to establish and maintain graft tolerance in transplant recipients. For many years, it has been hypothesised that due to their inherent mechanisms of antigen presentation and capacity for migration systemically, DCs represent an appealing cell type to manipulate ex vivo and re-administer to recipients. Pulsing such cells with donor antigen in an environment that polarizes them to a tolerogenic phenotype could, therefore, generate a negative cellular vaccine that can induce antigen specific tolerance in both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, by virtue of the semi-direct pathway.

Tol-DCs and transplant immunotherapy

The apparent pro-tolerogenic properties of immature DCs makes them excellent candidates for use in establishing transplant tolerance. Indeed, their minimal surface expression of costimulatory molecules and MHC Class IIlo phenotype reduces immunogenicity, whilst continued antigen presentation, albeit at low levels, promotes the induction of Tregs [58]. Stimulation of alloreactive naïve CD4+ T cells with iDCs, in comparison to matured DCs, has been shown to induce significantly weaker proliferation in culture, which declines further with repeated stimulations, ultimately resulting in the generation of non-proliferative, anergic CD4+ T cells. In addition, these T cells inhibit antigen-stimulated Th1 cell proliferation in coculture, suggesting a regulatory phenotype has been acquired [59]. However, a significant problem with the use of immature DCs is their unstable phenotype. The natural maturation process of DCs following administration into an in vivo system, particularly into an inflammatory environment such as that occurring following allograft transfer, would be deleterious and unpredictable. A population of tol-DCs that retain their phenotype under both steady state and inflammatory conditions is, therefore, required for safe attempts to induce transplant tolerance.

The use of both recipient (autologous) and donor tol-DCs has been evaluated in small animal models of transplantation tolerance. In these studies, both sources have been efficacious in promoting graft tolerance. However, donor and recipient tol-DCs operate via different mechanisms. Morelli et al. have indicated that intravenously-administered, maturation-resistant allogeneic DCs as a source of donor antigen can prolong cardiac allograft survival without direct interaction with recipient T cells. These allogeneic cells were short lived, and functioned as stores of donor antigen which were subsequently reprocessed by recipient DCs, presented via the indirect pathway and utilised to upregulate FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. A similar outcome can also be achieved by administering apoptotic donor DCs [60]. In contrast, administration of recipient DCs, which might be expected to survive for longer periods of time (up to two weeks), are able to acquire, process and present donor antigen to endogenous T cells and promote antigen specific tolerance. When compared side-by-side, it appears that syngeneic DCs have a greater effect in lengthening cardiac allograft survival than allogeneic DCs (median 22.5 days vs. median 16.5 days) [61].

In mouse models, tol-DCs generated from gene modification, pharmacological modification and cytokine induction have all improved graft survival. Pharmacological modifications to enhance DC tolerogenicity, including rapamycin, mitomycin-C and dexamethasone, have been the most consistent and effective method to extend graft survival [62]. For example, a single infusion of rapamycin-treated allo-Ag pulsed DCs prior to transplantation significantly prolonged cardiac allograft survival, whilst multiple infusions led to graft survival of longer than 100 days in 40% of recipients [63]. Cuturi's group has previously shown a combination treatment of recipient immature bone marrow DCs (bmDCs) with suboptimal LF 15-0195 immunosuppression induces definitive cardiac allograft acceptance in 92% of recipients [64]. Other strategies to induce tol-DCs have included use of viral transfection. DCs transfected with IDO administered to mice prior to cardiac allografting resulted in prolonged graft survival [65], whilst adenoviral vector delivery of CTLA4-Ig to DCs, in combination with NF-κB blockade results in promotion of T cell apoptosis and prolongation of heart allograft survival in MHC-mismatched rodents [66]. Administration of tolerogenic IDO+ DCs generated by α1-antitrypsin priming, a potent immunoregulatory serpin, also significantly lengthened kidney allograft survival in rats, and is associated with an expansion of Tregs in vivo [67]. Concomitant treatment with 1-methyltryptophan (1-MT), an IDO inhibitor, abolishes this graft-specific tolerance.

In small animal models, tol-DCs have been used to induce donor-specific non-responsiveness in various tissue allografts, including intestinal [68], [69], liver [70], [71], [72], islet [73] and skin transplants [74], [75] and kidney allografts in rhesus macaques [76]. Tol-DCs may have particular advantages in induction of transplant tolerance towards pancreatic islets. A key obstacle in achieving pancreatic islet graft tolerance is the reservoir of islet-specific CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells that is established at the onset of Type 1 diabetes and may be reactivated to become a significant source of graft rejection following islet transplantation. However, DCs may be uniquely equipped to inactivate these deleterious populations and have terminated anti-islet CD8+ T cell responses in murine studies [77]. Therefore, in the context of graft rejection driven by memory T cells, tol-DC immunotherapy may be more efficacious in attenuating rejection than other regulatory immunotherapies, such as Tregs.

Despite success in small animal models, few clinical studies have investigated the use of autologous or allogeneic tol-DCs in establishing tolerance following transplantation. The One Study, an ongoing multicenter trial evaluating a range of immunoregulatory cell therapies in solid organ transplantation, is a trial investigating the efficacy of autologous tol-DCs in establishing and maintaining renal transplant tolerance. In this study, tol-DCs are derived from CD14+ monocytes isolated from peripheral blood by leukapheresis and elutriation, which are subsequently cultured with low concentrations of GM-CSF in the absence of other cytokines or immunosuppressive drugs. This previously verified protocol, in both rodent and human, generates maturation-resistant, phenotypically-immature DCs. The study will determine the incidence of biopsy-confirmed acute graft rejection over the course of sixty weeks post-surgery, following intravenous injection of tol-DCs and concomitant tapering of immunosuppression medication in sixteen patients. As secondary outcome measures, the study is also measuring the total immunosuppressive burden exerted on the patient, incidence of post-transplant dialysis and graft loss and incidence of neoplasia. In addition to tol-DC efficacy, the study is also examining the efficacy of Treg and macrophage subpopulations at other centres. Results from the trial are expected during the autumn of 2018. Whilst high DC numbers are being injected into patients (1 × 106 cells/kg), the systemic nature of administration (via slow peripheral venous access) may perhaps restrict the number of tol-DCs that extravasate into the engrafted organ and ultimately process and present donor antigen via the semi-direct pathway. Methods by which administered DCs could be targeted to and retained within the transplanted organ, associated lymphatics and spleen could, therefore, offer enhanced efficacy over standard intravenous injection.

Autoimmunity

The exact aetiology of autoimmune diseases, which are thought to affect more than 5% of the global population, remains unclear, but is thought to result from failure of initial tolerance induction (central tolerance) or a breakdown in maintenance of established peripheral tolerance. This may be due to pathogenic insults, such as microbial infection, chronic inflammation or neoantigen generation through mutation. Whilst many autoimmune diseases can be effectively managed with the use of immunosuppressive therapies, there are significant deleterious consequences associated with the use of immunotherapy. For example, due to the critical involvement of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α in co-ordinating effective host immune responses against microbial infection, anti-TNF therapy, utilised for rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease and psoriasis, predisposes patients to severe bacterial infections [78] and promotes reactivation of latent tuberculosis [79], [80]. Generalised immunosuppression achieved by such treatments also increases the incidence of solid organ and haematological neoplasms [81]. Since these immunomodulatory therapies do not eliminate the cause of autoimmunity, treatment must be sustained indefinitely. As such, it is of significant interest to develop a therapy that can re-establish tolerance to the offending antigen with minimal treatments and maintain this tolerance indefinitely.

Tol-DCs and autoimmunity immunotherapy

Mouse studies have identified that tol-DCs have potential for clinical application for the treatment of inflammatory arthritis. Using immature DCs transfected with IL-4, murine collagen induced arthritis was effectively treated in vivo. Intravenous injection of the modified cells resulted in rapid migration to the liver and lymphatics and ultimately near complete suppression of the disease for four weeks post-treatment [82]. In vitro data suggest these effects to be as a result of IFN-γ suppression from splenocytes following collagen challenge and a reduction in IgG2 isotype antibodies produced against type II collagen. DCs genetically modified to express FasL are similarly effective in suppressing disease establishment and promoting disease amelioration [83], [84]. This amelioration coincides with the upregulation of CD4+CD25+ FoxP3+ iTreg cells [85]. Rosiglitazone, a PPAR-γ selective agonist, has recently been utilised to generate tol-DCs that demonstrate therapeutic effects in the treatment of murine collagen induced arthritis. Subcutaneous injections of antigen loaded, rosiglitazone cultured immature DCs reduced the clinical scoring and histological severity of arthritis in mice, and was associated with a highly significant reduction in ex vivo IFN-γ production by isolated splenocytes [86]. These studies have identified that tol-DCs can treat inflammatory arthritis by suppressing humoral and cell-mediated arms of the immune response.

Antigen-pulsed tol-DCs may also be a useful cell based therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which is mediated predominantly by antinuclear antibodies. Recent in vitro data have shown that knockdown of RelB, a key member of the NF-κB family involved in DC maturation, results in the generation of DCs with a semi-mature phenotype and reduced costimulatory molecule expression. RelB-modified DCs derived from lupus prone mice produce minimal IL-12p70 and induce a hyporesponsive state in autoreactive splenic T cells [87]. In human studies, VitD3 and dexamethasone conditioned tol-DCs derived from SLE patients have been shown to attenuate T cell activation and proliferation in mixed leukocyte reactions, and are capable of inducing Tregs from naïve T cells [88]. Future clinical studies are required to determine whether tol-DCs can effectively treat SLE.

Tol-DCs have also displayed promising results in models of multiple sclerosis (MS). Using VitD3 cultured tol-DCs pulsed with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), a critical autoantigen, Mansilla et al. have demonstrated reduced disease incidence, induction of Tregs and IL-10, and consequently reduction in the severity of signs of disease [89]. These results have since been repeated with the use of cryopreserved VitD3-treated tol-DCs pulsed with MOG peptide [90]. The maintenance of the tolerogenic phenotype following thawing is a significant finding for clinical application, as the ability to freeze–thaw cell stocks would remove the need for patients to undergo repeated leukapheresis procedures for freshly-isolated DCs and allow treatments to be immediately available, avoiding prolonged in vitro monocyte-to-DC differentiation cultures. The therapeutic effects of endogenous tol-DC in models of MS have also been demonstrated in depletion experiments. Selective depletion of CD11c+CD11b+ DCs and immature DCs with the use of clodronate-loaded liposomes significantly blocks the disease suppressing effects of intravenous soluble MOG administration, as measured by clinical scoring. Depletion of these tol-DCs was associated with a loss of MOG-induced T cell tolerance, normally characterised by an increase in prevalence of FoxP3+ cells and decreased production of the inflammatory cytokines IL-2, IFN-γ and IL-17 [91].

In vitro studies of human cells derived from multiple sclerosis patients suggest that tol-DC therapy may hold promise for inducing antigen specific tolerance in the clinical setting. Tol-DCs have been successfully generated from monocytes of relapsing-remitting MS (RR-MS) patients, using VitD3 enhanced cultures, and have displayed the desired stable semi-mature phenotype and anti-inflammatory properties in vitro. Furthermore, tol-DCs loaded with myelin peptide were shown to efficiently inhibit antigen-specific responses among autoreactive T cells derived from RR-MS patients [92]. The first-in-man clinical trials of myelin-derived peptide pulsed tol-DCs in MS patients, to determine safety and tolerability, are due to begin this year [93], [94].

Lymphocytic infiltration of the pancreas and subsequent autoimmune attack of beta islet cells is considered the major pathological process driving Type I diabetes (T1D) mellitus. As such, therapies promoting pancreas-specific antigen tolerance, particularly when provided in early childhood, may be sufficient to impede further islet cell loss and the development of diabetes. In support of these findings, in vitro studies of T1D patient-derived lymphocytes and DCs have shown that insulin and GAD65 loaded monocyte-derived tol-DCs induced T cell hyporesponsiveness in mixed leukocyte reactions and reduced IFN-γ and IL-2 secretion in comparison to control, conventional DCs (cDCs). In addition, lymphocytes previously stimulated with tol-DCs and subsequently rechallenged with antigen loaded cDCs exhibited stable hyporesponsiveness in a subset of patients, indicative of T cell tolerisation [95].

Tol-DCs have also shown promise in models of inflammatory bowel disease. Severe combined immune deficient (SCID) mice adoptively transferred with CD4+CD25− T cells, leading to the development of wasting disease and colitis, exhibit attenuated weight loss and gut pathology following administration of dexamethasone/VitD3-conditioned tol-DCs [96]. IL-10-treated tol-DCs have demonstrated a similar therapeutic effect in the SCID model [97]. Tol-DCs pulsed with carbonic anhydrase I, a caecal bacterial antigen implicated to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) pathogenesis, ameliorated macroscopic and histological signs of experimental colitis in mice and was associated with raised FoxP3+ Treg numbers in mesenteric lymph nodes [98]. These data support the suggestion that tol-DCs may provide therapeutic benefit in inflammatory bowel disease patients.

Clinical trials of tol-DCs for treatment of autoimmunity

In contrast to transplantation, a number of Phase I clinical trials have been completed, investigating the use of tol-DCs for immune intervention in autoimmunity.

The identification of highly disease specific, circulating autoreactive T cells and autoantibodies against citrullinated peptide antigens in the serum of around 76% of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients [99], [100], [101] indicates such individuals may be receptive to tolerising immunotherapy, such as tol-DC administration. The recently developed “Rheumavax” therapy consists of autologous DCs rendered tolerogenic through NF-κB inhibitor exposure and subsequently pulsed with four citrullinated peptide antigens [102]. In an open-label, prospective Phase I clinical trial, a single intradermal injection of up to 4.5 × 106 DCs was shown to be well tolerated in citrullinated peptide-specific RA patients, and was associated with an increase in the Treg/Teff cell ratio by 25% or more in 11 of the 15 treated patients [103]. A similar autologous, antigen-pulsed DC therapy, designated CreaVax-RA, was well-tolerated in RA patients and demonstrated preliminary signs of efficacy by significantly reducing antigen-specific autoantibody levels in 55.6% of autoantibody positive patients [104].

A Phase I, dose escalation clinical trial of autologous tol-DC therapy for inflammatory arthritis involved injection of tol-DCs, differentiated in vitro from CD14+ monocytes, isolated via leukapheresis, and loaded with autologous synovial fluid antigens. No worsening of symptoms was recorded in the target joints during days 1–5 following administration, confirming short-term therapeutic safety. Synovitis improved in one out of three participants in both the 1 × 106 and 3 × 106 cells dosage cohorts, and in both patients receiving 10 × 106 cells. No improvement was observed in the three control participants [105]. These safety and early efficacy data indicate that tol-DC therapy may be a promising treatment strategy for inflammatory arthritis patients, warranting further studies involving a greater number of participants.

Phase I clinical trials for tol-DC therapy in Type I diabetes has also been investigated. Intradermal administration of 10 × 106 DCs, either unmanipulated or engineered towards a tolerogenic phenotype ex vivo, was safely tolerated by all T1D patients, with no adverse events recorded over the course of 2 months. Administration of engineered DCs was associated with a statistically significant increase in suppressive B220+CD11c− B cells [106] during the administration period [107]. A multicentre Phase II RCT evaluating the efficacy of autologous tol-DCs in recent onset T1D has been planned [108].

A Phase I trial of monocyte-derived autologous tol-DC therapy has recently been completed in patients with refractory Crohn's disease. Therapeutic safety was confirmed for both single and three biweekly intraperitoneal injections of tol-DCs [109]. A clinical response, defined as a decrease in the Clinical Activity Score CDAI of ≥100, was observed in two patients (22%) and clinical remission (CDAI below 150 points) was observed in another, yet the mean decrease in CDAI was nonsignificant (274–222, p = 0.3). Currently ongoing trials include a Phase I evaluation of highly localised, intralesional administration of tol-DCs in patients with refractory Crohn's disease [110]. Future trials should investigate the therapeutic benefit of tol-DCs in a larger cohort of Crohn's patients, as well as in patients with related pathologies, including ulcerative colitis.

Allergy

In addition to autoimmunity, excessive immune responses specific for otherwise innocuous antigens may result in allergic reactions. Such immune responses can lead to the development of a number of commonly occurring diseases, including asthma, urticaria and dermatitis. The key involvement of Th2 cells and IgE secreting B cells in the allergic reactions mean that therapies that can establish tolerance to the offending allergen can potentially provide curative treatment. At present, the only such approved therapy is allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT), involving exposure to escalating concentrations of allergen. This “low zone tolerance”, describing the repetitive exposure of individuals to low doses of allergen, has been shown to critically depend on interactions between FoxP3+ Treg cells and tol-DCs in mouse experiments [111], [112]. By extension, it is thought that the administration of allergen-pulsed tol-DCs could provide a stimulus for allergen-specific tolerance induction. The switch from a Th2 to a Treg-based allergen specific response, driven by tol-DC administration, may result in the suppression of other immune cells involved in the allergic pathology, including eosinophils and IgE-secreting B cells.

Tol-DCs and allergy immunotherapy

Immunomodulation of allergic asthma is a particularly active area of current tol-DC therapy research. Whilst immunogenic DCs play a key role in the priming of allergen-specific Teffs and induction of airway hyperresponsiveness in allergic asthma [113], tol-DCs have been demonstrated to suppress clinical features of asthma [114]. In vitro studies confirm the ability of tol-DCs to downregulate proallergic Th2 proliferative and cytokine responses [115], whilst IL-10 treated tol-DCs have demonstrated potent suppression of airway hyperresponsiveness in mouse models of asthma [116], [117], [118]. Single tol-DC treatments were sufficient for long-lived suppression of Th2 responses [119]. Recent studies using human tol-DCs to induce antigen specific Treg cells and suppress patient-derived, allergen-specific Teff responses in vitro have provided the basis for future clinical trials. Other forms of allergy, such as contact dermatitis, may also be amenable to tol-DC therapy. Dexamethasone-treated tol-DCs derived from peripheral blood samples of individuals with IgE-mediated latex allergy inhibit allergen-specific T cell proliferation and IgE production in vitro and induce IL-10 competent Tregs [120]. Tol-DCs, therefore, demonstrate potential therapeutic effects in models of allergic disease and further investigation and future clinical trials will determine whether these findings can be translated to a clinical setting.

Future challenges

Whilst the pre-clinical and early clinical trial data for tol-DC therapy is encouraging, there are some significant questions that must be addressed to ensure the development of consistent, safe and efficacious treatments. One of the major concerns surrounding tol-DC therapy is the potential for generating cells with an unstable tolerogenic phenotype. The potentially unstable phenotype of tol-DCs has been demonstrated in experimental models. For example, TNF-induced semi-mature DCs that lack the capacity to secrete inflammatory cytokines have been found to be capable of differentiating further, under the influence of lipopolysaccharide, into immunogenic DCs capable of stimulating Th1 and Th2 mediated immune responses [121]. Furthermore, semi-mature DCs which are ordinarily tolerogenic at low doses, and therapeutic in collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) mouse models, exhibit immunogenic properties when inoculated at higher doses with reduced capacity for FoxP3+ Treg cell induction [122]. A valid concern is, therefore, the risk of inducing an immune response to the target antigen, rather than inducing tolerance.

This concern is particularly acute in the setting of transplantation. Here, the presence of a pro-inflammatory environment mediated by the surgery, ischaemia-reperfusion injury and the high burden of necrotic tissue may result in APC upregulation of costimulatory molecules and secretion of inflammatory cytokines [3]. Strategies to maintain the stability of tol-DCs or limit the pro-inflammatory environment that accompanies transplantation may, thus, facilitate induction of tolerance using tol-DCs in the transplantation setting.

Another key question relates to the strategy utilised to generate DCs with a truly tolerogenic phenotype. Whilst DCs may be isolated from a number of anatomical sites, including bone marrow and the blood via leukapheresis, it is likely that the most suitable source of DCs for therapeutic use is from peripheral blood derived monocytes, isolated from a single blood draw, and subsequently differentiated ex vivo under specific culture conditions. A variety of strategies could be employed during this differentiation process to polarize these DCs towards a tolerogenic phenotype, including addition of VitD3 or the recombinant cytokines IL-10, TGF-β1 and VEGF, withdrawal of GM-CSF, co-culture with apoptotic cells or immunosuppressive agents such as mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), tacrolimus, rapamycin and dexamethasone, or the use of costimulatory blockade, such as CTLA-4-Ig or monoclonal antibodies specific for CD40L or OX40L. Whilst a range of methods have been described in the literature, few studies have directly compared the stability and overall efficacy of tol-DCs generated by different means. Further work is therefore warranted to establish which method, or perhaps combination of methods, is most suitable to generate tol-DCs in the clinical setting.

Quality control of immunotherapies is also of critical importance. A recent study has indicated that certain surface phenotypes of tol-DCs may, in fact, promote autoimmune disease [123]. Interestingly, purified CD11c+ VitD3-treated DCs, which, in in vitro tests, showed reduced capacity to prime T cells, were equally capable of stimulating murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) as fully immunogenic, antigen-pulsed CD11c+ DCs. In vitro analysis of DC functionality alone is therefore likely to be insufficient to predict in vivo behaviour, and robust assays should be performed prior to therapeutic use.

In the transplantation setting, it is currently unclear whether the most effective method of achieving tolerance would be to administer antigen-pulsed tol-DCs or administer antigen-naïve tol-DCs that subsequently take up alloantigens following donor engraftment. The former, involving ex vivo pulsing of cultured tol-DCs with selected donor antigens, would maximize the chance of administered DCs processing and presenting appropriate antigen to the recipient's lymphocyte repertoire. However, this method does not mimic normal physiological conditions of antigen acquisition and limits the range of donor antigens that can be presented. In addition, this strategy bypasses the semi-direct pathway of antigen presentation. In contrast, administration of antigen-naïve tol-DCs is likely to be a far less efficient method of generating donor antigen-presenting tol-DCs, due to the inevitable systemic dispersion of cells following inoculation. However, more natural conditions of antigen acquisition and presentation in vivo will permit antigen presentation through the semi-direct pathway, influencing both CD4 and CD8 lineages from a single DC.

Establishing safe and ethically tolerable protocols for clinical trials of tol-DC immunotherapy, particularly in the transplant setting, is also challenging. In order to demonstrate efficacy of tol-DC therapy in isolation, patients in intervention groups must relinquish standard-of-care therapies. Patients weaned off treatments must be carefully monitored on a regular basis to identify early signs of disease recurrence and graft failure. Due to the efficacy of current medications used for autoimmune disease and transplantation, it may be challenging to satisfy ethical standards and implement tol-DC strategies.

Future opportunities

Genetic modification of tol-DCs to over-express molecules associated with a tolerogenic phenotype and/or to silence immunostimulatory molecules represents a promising approach to maximize potency and ensure consistency among DC immunotherapies. Classically, DCs are seen to be relatively resistant to genetic modification, often losing viability following manipulation due to their sustained maturation. As such, modification of the genome must usually occur at an earlier stage of the differentiation pathway, typically at the level of the monocyte. The arrival of novel, highly targeted genome editing tools such as CRISPR-Cas9 promises to alleviate many of the issues associated with genetic modification. Suggested targets for knock-out include costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80 and CD86, ensuring DCs can never provide a “signal 2” required for T cell activation, but instead be inclined to promote tolerance. In addition, over-expression of apoptosis inducing molecules, such as FasL, has been shown to generate so called “killer” DCs with a tolerance-inducing phenotype [124], [125]. At present, minimal literature exists on the generation and functionality of CRISPR-Cas9 modified DCs, but this will likely change in the coming years due to rapid improvements and uptake of such techniques.

The short in vitro and in vivo lifespan of terminally differentiated DCs, combined with their inherent resistance to genetic modification and the transient effects of RNA modification mean that less differentiated “source cells” are likely needed for culturing and cryopreservation. Such “source cells” could then be differentiated to tol-DCs when required for treatment, to maximize cell viability and cell functionality. Although monocytes could perform this function of “source cell”, they too have a limited lifespan in culture and patients would require repeated blood draws to maintain monocyte cell cultures for long periods. A superior “source cell” might, therefore, be pluripotent stem cells, either embryonic stem cells [126] or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) [127], typically derived from reprogrammed patient dermal fibroblasts. There are a number of advantages to using iPSC for the generation of tol-DCs [128]. Firstly, DCs differentiated from iPSC display an unusual, naturally tolerogenic phenotype, reminiscent of the phenotype expressed by DCs isolated from foetal tissue. This would be clearly advantageous for the clinical applications described here and may mean minimal pharmacological or genetic modifications would be required to achieve true tol-DCs. Due to the indefinite replicative potential of iPSC, a single biopsy is all that would be required to establish a cell line capable of significant expansion, to a level required for immunotherapy. iPSC, unlike DCs, are also amenable to genetic modification, allowing investigators to derive clonal populations of genetically-modified cells that would retain these changes throughout the differentiation process to DCs. Finally, cell viability of iPSC following cryopreservation is far higher than that of terminally differentiated DCs, which would permit patient's cell lines to be cryogenically stored for extended periods, until required [128].

Conclusions

As the major professional APC of the immune system, DCs are uniquely placed at the heart of the immune response, functioning to link the innate and adaptive systems. As a consequence, DCs are highly specialised to interact with and control a vast range of immune cells. Such characteristics make DCs a target for modification, to permit the induction and maintenance of antigen-specific tolerance. This would permit the development of “negative cellular vaccines” for transplantation, autoimmune disease and allergy. Both in vitro and in vivo studies of rodent and human cells, in addition to early data from clinical trials indicate significant promise for clinical tol-DC therapy. New technologies, including the development of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing and iPSC, may prove fruitful future avenues for overcoming the current obstacles and advancing pre-clinical work from the bench to the bedside.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Tim Davies, Herman Waldmann and Stephen Cobbold for helpful discussions. Research into dendritic cells in the authors' laboratory is funded by the Rosetrees Trust (Grant A1372), the Medical Research Council Confidence in Concept Fund (Grant MC-PC-15029), the CRUK Oxford Centre Development Fund (Grant CRUKDF-0716-PF) and the Guy Newton Translational Research Fund (Grant GN-05).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Gardner J.M., Devoss J.J., Friedman R.S., Wong D.J., Tan Y.X., Zhou X. Deletional tolerance mediated by extrathymic Aire-expressing cells. Science. 2008;321:843–847. doi: 10.1126/science.1159407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Idoyaga J., Fiorese C., Zbytnuik L., Lubkin A., Miller J., Malissen B. Specialized role of migratory dendritic cells in peripheral tolerance induction. J Clin Invest. 2014;4:1–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI65260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sauter B., Albert M.L., Francisco L., Larsson M., Somersan S., Bhardwaj N. Consequences of cell death: exposure to necrotic tumor cells, but not primary tissue cells or apoptotic cells, induces the maturation of immunostimulatory dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:423–434. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kushwah R., Wu J., Oliver J.R., Jiang G., Zhang J., Siminovitch K.A. Uptake of apoptotic DC converts immature DC into tolerogenic DC that induce differentiation of Foxp3+ Treg. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1022–1035. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamazaki S., Iyoda T., Tarbell K., Olson K., Velinzon K., Inaba K. Direct expansion of functional CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells by antigen-processing dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:235–247. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walunas T.L., Bakker C.Y., Bluestone J.A. CTLA-4 ligation blocks CD28-dependent T cell activation. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2541–2550. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinbrink K., Graulich E., Kubsch S., Knop J., Enk A.H. CD4+ and CD8+ anergic T cells induced by interleukin-10-treated human dendritic cells display antigen-specific suppressor activity. Blood. 2002;99:2468–2476. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Süss G., Shortman K. A subclass of dendritic cells kills CD4 T cells via Fas/Fas-ligand-induced apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1789–1796. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Halteren A.G.S., Tysma O.M., Van Etten E., Mathieu C., Roep B.O. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 or analogue treated dendritic cells modulate human autoreactive T cells via the selective induction of apoptosis. J Autoimmun. 2004;23:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurts C., Heath W.R., Kosaka H., Miller J.F., Carbone F.R. The peripheral deletion of autoreactive CD8+ T cells induced by cross-presentation of self-antigens involves signaling through CD95 (Fas, Apo-1) J Exp Med. 1998;188:415–420. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu L., Qian S., Hershberger P.A., Rudert W.A., Lynch D.H., Thomson A.W. Fas ligand (CD95L) and B7 expression on dendritic cells provide counter- regulatory signals for T cell survival and proliferation. J Immunol. 1997;158:5676–5684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fallarino F., Vacca C., Orabona C., Belladonna M.L., Bianchi R., Marshall B. Functional expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by murine CD8 alpha(+) dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2002;14:65–68. doi: 10.1093/intimm/14.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grohmann U., Fallarino F., Silla S., Bianchi R., Belladonna M.L., Vacca C. CD40 ligation ablates the tolerogenic potential of lymphoid dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:277–283. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grohmann U., Fallarino F., Bianchi R., Belladonna M.L., Vacca C., Orabona C. IL-6 inhibits the tolerogenic function of CD8 alpha+ dendritic cells expressing indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J Immunol. 2001;167:708–714. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izawa T., Kondo T., Kurosawa M., Oura R., Matsumoto K., Tanaka E. Fas-independent T-cell apoptosis by dendritic cells controls autoimmune arthritis in MRL/lpr mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qian C., Qian L., Yu Y., An H., Guo Z., Han Y. Fas signal promotes the immunosuppressive function of regulatory dendritic cells via the ERK/??-catenin pathway. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:27825–27835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.425751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schenk A.D., Nozaki T., Rabant M., Valujskikh A., Fairchild R.L. Donor-reactive CD8 memory T cells infiltrate cardiac allografts within 24-h posttransplant in naive recipients. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:1652–1661. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donckier V., Craciun L., Miqueu P., Troisi R.I., Lucidi V., Rogiers X. Expansion of memory-type CD8+ T cells correlates with the failure of early immunosuppression withdrawal after cadaver liver transplantation using high-dose ATG induction and rapamycin. Transplantation. 2013;96:306–315. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182985414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koyama I., Nadazdin O., Boskovic S., Ochiai T., Smith R.N., Sykes M. Depletion of CD8 memory t cells for induction of tolerance of a previously transplanted kidney allograft. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1055–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nasreen M., Waldie T.M., Dixon C.M., Steptoe R.J. Steady-state antigen-expressing dendritic cells terminate CD4+ memory T-cell responses. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2016–2025. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenna T.J., Thomas R., Steptoe R.J. Steady-state dendritic cells expressing cognate antigen terminate memory CD8+ T-cell responses. Blood. 2008;111:2091–2100. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kenna T.J., Waldie T., McNally A., Thomson M., Yagita H., Thomas R. Targeting antigen to diverse APCs inactivates memory CD8+ T cells without eliciting tissue-destructive effector function. J Immunol. 2010;184:598–606. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torres-Aguilar H., Aguilar-Ruiz S.R., González-Pérez G., Munguía R., Bajaña S., Meraz-Ríos M.a. Tolerogenic dendritic cells generated with different immunosuppressive cytokines induce antigen-specific anergy and regulatory properties in memory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:1765–1775. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehlers M.R., Rigby M.R. Targeting memory T cells in Type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:84. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0659-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Page A.J., Ford M.L., Kirk A.D. Memory T-cell-specific therapeutics in organ transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14:643–649. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328332bd4a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afzali B., Mitchell P.J., Scottà C., Canavan J., Edozie F.C., Fazekasova H. Relative resistance of human CD4 + memory T cells to suppression by CD4 +CD25 + regulatory T cells. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1734–1742. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J., Brook M.O., Carvalho-Gaspar M., Zhang J., Ramon H.E., Sayegh M.H. Allograft rejection mediated by memory T cells is resistant to regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19954–19959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704397104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo X., Tarbell K.V., Yang H., Pothoven K., Bailey S.L., Ding R. Dendritic cells with TGF-beta1 differentiate naive CD4+CD25- T cells into islet-protective Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2821–2826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611646104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamazaki S., Bonito A.J., Spisek R., Dhodapkar M., Inaba K., Steinman R.M. Dendritic cells are specialized accessory cells along with TGF-β for the differentiation of Foxp3+ CD4+ regulatory T cells from peripheral Foxp3- precursors. Blood. 2007;110:4293–4302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-088831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamazaki S., Dudziak D., Heidkamp G.F., Fiorese C., Bonito A.J., Inaba K. CD8+ CD205+ splenic dendritic cells are specialized to induce Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:6923–6933. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coombes J.L., Siddiqui K.R.R., Arancibia-Cárcamo C.V., Hall J., Sun C.-M., Belkaid Y. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun C.-M., Hall J.A., Blank R.B., Bouladoux N., Oukka M., Mora J.R. Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1775–1785. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fehérvári Z., Sakaguchi S. Control of Foxp3+ CD25+CD4+ regulatory cell activation and function by dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1769–1780. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gru G. New insights into the molecular mechanism of interleukin-10- mediated immunosuppression. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:3–15. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0904484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsu P., Santner-Nanan B., Hu M., Skarratt K., Lee C.H., Stormon M. IL-10 potentiates differentiation of human induced regulatory T cells via STAT3 and Foxo1. J Immunol. 2015;195:3665–3674. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wakkach A., Fournier N., Brun V., Breittmayer J.P., Cottrez F., Groux H. Characterization of dendritic cells that induce tolerance and T regulatory 1 cell differentiation in vivo. Immunity. 2003;18:605–617. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gregori S., Tomasoni D., Pacciani V., Scirpoli M., Battaglia M., Magnani C.F. Differentiation of type 1 T regulatory cells (Tr1) by tolerogenic DC-10 requires the IL-10-dependent ILT4/HLA-G pathway. Blood. 2010;116:935–944. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Travis M.A., Reizis B., Melton A.C., Masteller E., Tang Q., Proctor J.M. Loss of integrin alpha(v)beta8 on dendritic cells causes autoimmunity and colitis in mice. Nature. 2007;449:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nature06110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unger W.W.J., Laban S., Kleijwegt F.S., Van Der Slik A.R., Roep B.O. Induction of Treg by monocyte-derived DC modulated by vitamin D3 or dexamethasone: differential role for PD-L1. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:3147–3159. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuipers H., Muskens F., Willart M., Hijdra D., van Assema F.B.J., Coyle A.J. Contribution of the PD-1 ligands/PD-1 signaling pathway to dendritic cell-mediated CD4+ cell activation. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2472–2482. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cederbom L., Hall H., Ivars F. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells down-regulate co-stimulatory molecules on antigen-presenting cells. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1538–1543. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200006)30:6<1538::AID-IMMU1538>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oderup C., Cederbom L., Makowska A., Cilio C.M., Ivars F. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4-dependent down-modulation of costimulatory molecules on dendritic cells in CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T-cell-mediated suppression. Immunology. 2006;118:240–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Awasthi A., Carrier Y., Peron J.P., Bettelli E., Kamanaka M., Flavell R.A. A dominant function for interleukin 27 in generating interleukin 10-producing anti-inflammatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1380–1389. doi: 10.1038/ni1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosser E.C., Mauri C. Regulatory B cells: origin, phenotype, and function. Immunity. 2015;42:607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volchenkov R., Karlsen M., Jonsson R., Appel S. Type 1 regulatory T cells and regulatory B cells induced by tolerogenic dendritic cells. Scand J Immunol. 2013;77:246–254. doi: 10.1111/sji.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parekh V.V., Prasad D.V.R., Banerjee P.P., Joshi B.N., Kumar A., Mishra G.C. B cells activated by lipopolysaccharide, but not by anti-Ig and anti-CD40 antibody, induce anergy in CD8+ T cells: role of TGF-beta 1. J Immunol. 2003;170:5897–5911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.5897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carter N.A., Vasconcellos R., Rosser E.C., Tulone C., Munoz-Suano A., Kamanaka M. Mice lacking endogenous IL-10-producing regulatory B cells develop exacerbated disease and present with an increased frequency of Th1/Th17 but a decrease in regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:5569–5579. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flores-Borja F., Bosma A., Ng D., Reddy V., Ehrenstein M.R., Isenberg D.A. CD19+CD24hiCD38hi B cells maintain regulatory T cells while limiting TH1 and TH17 differentiation. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:173ra23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun C.M., Deriaud E., Leclerc C., Lo-Man R. Upon TLR9 signaling, CD5+ B cells control the IL-12-dependent Th1-priming capacity of neonatal DCs. Immunity. 2005;22:467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walker M.R., Kasprowicz D.J., Gersuk V.H., Bènard A., Van Landeghen M., Buckner J.H. Induction of FoxP3 and acquisition of T regulatory activity by stimulated human CD4 + CD25 – T cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1437–1443. doi: 10.1172/JCI19441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dieckmann D., Bruett C.H., Ploettner H., Lutz M.B., Schuler G. Human CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory, contact-dependent T cells induce interleukin 10-producing, contact-independent type 1-like regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;196:247–253. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andersson J., Tran D.Q., Pesu M., Davidson T.S., Ramsey H., O'Shea J.J. CD4+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells confer infectious tolerance in a TGF-beta-dependent manner. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1975–1981. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DiPaolo R.J., Brinster C., Davidson T.S., Andersson J., Glass D., Shevach E.M. Autoantigen-specific TGFbeta-induced Foxp3+ regulatory T cells prevent autoimmunity by inhibiting dendritic cells from activating autoreactive T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:4685–4693. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lan Q., Zhou X., Fan H., Chen M., Wang J., Ryffel B. Polyclonal CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells induce TGFbeta-dependent tolerogenic dendritic cells that suppress the murine lupus-like syndrome. J Mol Cell Biol. 2012;4:409–419. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjs040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benichou G., Yamada Y., Yun S.H., Lin C., Fray M., Tocco G. Immune recognition and rejection of allogeneic skin grafts. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:757–770. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Auchincloss H., Lee R., Shea S., Markowitz J.S., Grusby M.J., Glimcher L.H. The role of “indirect” recognition in initiating rejection of skin grafts from major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:3373–3377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herrera O.B., Golshayan D., Tibbott R., Ochoa F.S., James M.J., Marelli-Berg F.M. A novel pathway of alloantigen presentation by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:4828–4837. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.4828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yates S.F., Paterson A.M., Nolan K.F., Cobbold S.P., Saunders N.J., Waldmann H. Induction of regulatory T cells and dominant tolerance by dendritic cells incapable of full activation. J Immunol. 2007;179:967–976. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jonuleit H., Schmitt E., Schuler G., Knop J., Enk A.H. Induction of interleukin 10-producing, nonproliferating CD4(+) T cells with regulatory properties by repetitive stimulation with allogeneic immature human dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1213–1222. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Divito S.J., Wang Z., Shufesky W.J., Liu Q., Tkacheva O.A., Montecalvo A. Endogenous dendritic cells mediate the effects of intravenously injected therapeutic immunosuppressive dendritic cells in transplantation. Blood. 2010;116:2694–2705. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-251058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pêche H., Trinité B., Martinet B., Cuturi M.C. Prolongation of heart allograft survival by immature dendritic cells generated from recipient type bone marrow progenitors. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:255–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu W., Shan J., Li Y., Luo L., Sun G., Zhou Y. Adoptive transfusion of tolerance dendritic cells prolongs the survival of cardiac allograft: a systematic review of 44 basic studies in mice. J Evid Based Med. 2012;5:139–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-5391.2012.01191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taner T., Hackstein H., Wang Z., Morelli A.E., Thomson A.W. Rapamycin-treated, alloantigen-pulsed host dendritic cells induce Ag-specific T cell regulation and prolong graft survival. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:228–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2004.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bériou G., Pêche H., Guillonneau C., Merieau E., Cuturi M.C. Donor-specific allograft tolerance by administration of recipient-derived immature dendritic cells and suboptimal immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2005;79:969–972. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000158277.50073.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li C., Liu T., Zhao N., Zhu L., Wang P., Dai X. Dendritic cells transfected with indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase gene suppressed acute rejection of cardiac allograft. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;36:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bonham C.A., Peng L., Liang X., Chen Z., Wang L., Ma L. Marked prolongation of cardiac allograft survival by dendritic cells genetically engineered with NF-kappa B oligodeoxyribonucleotide decoys and adenoviral vectors encoding CTLA4-Ig. J Immunol. 2002;169:3382–3391. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen G., Li J., Chen L., Lai X., Qiu J. α1-Antitrypsin-primed tolerogenic dendritic cells prolong allograft kidney transplants survival in rats. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;31:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu X., Gao X., Zhao X., Liao Y., Ji W., Li Q. PU.1-Silenced dendritic cells induce mixed chimerism and alleviate intestinal transplant rejection in rats via a Th1 to Th2 shift. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;38:220–228. doi: 10.1159/000438623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen T., Xu H., Wang H.Q., Zhao Y., Zhu C.F., Zhang Y.H. Prolongation of rat intestinal allograft survival by administration of triptolide-modified donor bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Transpl Proc. 2008;40:3711–3713. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xie J., Wang Y., Bao J., Ma Y., Zou Z., Tang Z. Immune tolerance induced by RelB short-hairpin RNA interference dendritic cells in liver transplantation. J Surg Res. 2013;180:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang G.-Y., Yang Y., Li H., Zhang J., Li M.-R., Zhang Q. Rapamycin combined with donor immature dendritic cells promotes liver allograft survival in association with CD4(+) CD25(+) Foxp3(+) regulatory T cell expansion. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:192–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li L., Zhang S., Ran J., Liu J., Li Z., Li L. Mechanism of immune hyporesponsiveness induced by recipient- derived immature dendritic cells in liver transplantation rat. Chin Med Sci J. 2011;26:28–35. doi: 10.1016/s1001-9294(11)60016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ali A., Garrovillo M., Jin M.-X., Hardy M.A., Oluwole S.F. Major histocompatibility complex class I peptide-pulsed host dendritic cells induce antigen-specific acquired thymic tolerance to islet cells 1,2. Transplantation. 2000;69:221–226. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200001270-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Segovia M., Louvet C., Charnet P., Savina A., Tilly G., Gautreau L. Autologous dendritic cells prolong allograft survival through Tmem176b-dependent antigen cross-presentation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:1021–1031. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen Y., Lai H.S., Chiang B.L., Tseng S.H., Chen W.J. Tetrandrine attenuates dendritic cell-mediated alloimmune responses and prolongs graft survival in mice. Planta Med. 2010;76:1424–1430. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1240909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ezzelarab M.B., Zahorchak A.F., Lu L., Morelli A.E., Chalasani G., Demetris A.J. Regulatory dendritic cell infusion prolongs kidney allograft survival in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1989–2005. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coleman M.A., Jessup C.F., Bridge J.A., Overgaard N.H., Penko D., Walters S. Antigen-encoding bone marrow terminates islet-directed memory CD8+ T-cell responses to alleviate islet transplant rejection. Diabetes. 2016;65:1328–1340. doi: 10.2337/db15-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Galloway J., Hyrich K., Mercer L., Dixon W., Fu B., Ustianowski A. Anti-TNF therapy is associated with an increased risk of serious infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis especially in the first 6 months of treatment: updated results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register with special emph. Rheumatology. 2011;50:124–131. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Keane J., Gershon S., Wise R.P., Mirabile-Levens E., Kasznica J., Schwieterman W.D. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1098–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Martinez O.N., Noiseux C.R., Martin J.A.C., Lara V.G., Gregorio Marañón H.G. Reactivation tuberculosis in a patient with anti-TNF-alpha treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1665–1666. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bongartz T., Sutton A.J., Sweeting M.J., Buchan I., Matteson E.L., Montori V. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295:2275–2285. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.19.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kim S.H., Kim S., Evans C.H., Ghivizzani S.C., Oligino T., Robbins P.D. Effective treatment of established murine collagen-induced arthritis by systemic administration of dendritic cells genetically modified to express IL-4. J Immunol. 2001;166:3499–3505. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu Z., Xu X., Hsu H.C., Tousson A., Yang P.A., Wu Q. CII-DC-AdTRAIL cell gene therapy inhibits infiltration of CII-reactive T cells and CII-induced arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1332–1341. doi: 10.1172/JCI19209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim S.H., Kim S., Oligino T.J., Robbins P.D. Effective treatment of established mouse collagen-induced arthritis by systemic administration of dendritic cells genetically modified to express fasL. Mol Ther. 2002;6:584–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ning B., Wei J., Zhang A., Gong W., Fu J., Jia T. Antigen-specific tolerogenic dendritic cells ameliorate the severity of murine collagen-induced arthritis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Byun S.H., Lee J.H., Jung N.C., Choi H.J., Song J.Y., Seo H.G. Rosiglitazone-mediated dendritic cells ameliorate collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;115:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu H., Lo Y., Chan A., Law K.S., Mok M.Y. Rel B-modified dendritic cells possess tolerogenic phenotype and functions on lupus splenic lymphocytes in vitro. Immunology. 2016;149:48–61. doi: 10.1111/imm.12628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wu H.J., Lo Y., Luk D., Lau C.S., Lu L., Mok M.Y. Alternatively activated dendritic cells derived from systemic lupus erythematosus patients have tolerogenic phenotype and function. Clin Immunol. 2015;156:43–57. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mansilla M.J., Sellès-Moreno C., Fàbregas-Puig S., Amoedo J., Navarro-Barriuso J., Teniente-Serra A. Beneficial effect of tolerogenic dendritic cells pulsed with MOG autoantigen in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2015;21:222–230. doi: 10.1111/cns.12342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mansilla M.J., Contreras-Cardone R., Navarro-Barriuso J., Cools N., Berneman Z., Ramo-Tello C. Cryopreserved vitamin D3-tolerogenic dendritic cells pulsed with autoantigens as a potential therapy for multiple sclerosis patients. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:113. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0584-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang L., Li Z., Ciric B., Safavi F., Zhang G.-X., Rostami A. Selective depletion of CD11c+ CD11b+ dendritic cells partially abrogates tolerogenic effects of intravenous MOG in murine EAE. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46:2454–2466. doi: 10.1002/eji.201546274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Raïch-Regué D., Grau-López L., Naranjo-Gómez M., Ramo-Tello C., Pujol-Borrell R., Martínez-Cáceres E. Stable antigen-specific T-cell hyporesponsiveness induced by tolerogenic dendritic cells from multiple sclerosis patients. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:771–782. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cools N, Berneman Zwi. A “Negative” dendritic cell-based vaccine for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a first-in-human clinical trial. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02618902 [accessed 16.12.06].

- 94.Ramo C, Martinez-Caceres E. Tolerogenic dendritic cells as a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of multiple sclerosis patients (TOLERVIT-MS) (TOLERVIT-MS) 2016. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02903537 [accessed 16.12.06].

- 95.Segovia-Gamboa N., Rodriguez-Arellano M.E., Rangel-Cruz R., Sanchez-Diaz M., Ramirez-Reyes J.C., Faradji R. Tolerogenic dendritic cells induce antigen-specific hyporesponsiveness in insulin- and glutamic acid decarboxylase 65-autoreactive T lymphocytes from type 1 diabetic patients. Clin Immunol. 2014;154:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]