Abstract

Background

To investigate the injury pattern, mechanisms, severity, and mortality of the elderly hospitalized for treatment of trauma following motorcycle accidents.

Methods

Motorcycle-related hospitalization of 994 elderly and 5078 adult patients from the 16,548 hospitalized patients registered in the Trauma Registry System between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2013.

Results

The motorcycle-related elderly trauma patients had higher injury severity, less favorable outcomes, higher proportion of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), prolonged hospital and ICU stays and higher mortality than those adult motorcycle riders. It also revealed that a significant percentage of elderly motorcycle riders do not wear a helmet. Compared to patients who had worn a helmet, patients who had not worn a helmet had a lower first Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, and a greater percentage presented with unconscious status (GCS score ≤8), had sustained subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral contusion, severe injury (injury severity score 16–24 and ≥25), had longer hospital stay and higher mortality, and had required admission to the ICU.

Conclusions

Elderly motorcycle riders tend to present with a higher injury severity, worse outcome, and a bodily injury pattern differing from that of adult motorcycle riders, indicating the need to emphasize use of protective equipment, especially helmets, to reduce their rate and severity of injury.

Keywords: Elderly, Helmet, Injury Severity Score (ISS), Mortality, Motorcycle

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

With a rapid growth in the geriatric population, identification of high-risk distinct injury patterns in the elderly patients from those of adults may lead to improved health care. The purpose of this study is to investigate the injury pattern, severity, and mortality of the elderly patients treated for injuries sustained in motorcycle accidents in a level I trauma center in southern Taiwan using data from a population-based trauma registry.

What this study adds to the field?

This study revealed that elderly motorcycle riders are injured more severely, present with a different bodily injury pattern, and have higher mortality than adult riders. It also found that no helmet-wearing in a significant percentage of elderly motorcycle riders had put them at high risk of injury with worse outcome.

The elderly patients sustain distinct patterns of injuries from causes that differ from those of adults because of their unique anatomical, physiologic, and behavioral characteristics. The rapid growth in the geriatric population has had a considerable impact on healthcare system [1]. Injury in the elderly is increasing at a rate seven times that of adults [2]. In 2010, the elderly accounted for only 17% of the population but 55% of injury-related discharge in the United States [2]. In addition, there is strong evidence that elderly trauma patients are at an increased risk of morbidity and mortality compared with younger patients [3], [4], [5].

Motor vehicle collisions are a major cause of trauma among the elderly [6]. In Taiwan, motorcyclists are a major portion of the trauma population. This is of particular concern as the average age of motorcyclists is increasing [1]. However, motorcyclists are 35 times more likely than passenger-car occupants to die in a motor vehicle traffic crash and 8 times more likely to be injured per vehicle mile [7]. The advanced age had been shown to be an independent predictor of inpatient hospitalization, poor outcome, need for intensive care unit (ICU) care among motorcycle-related trauma patients [1], [8]. The identification of high-risk injury patterns may lead to improved care and ultimately further improvements in outcome in the elderly admitted to the hospital with trauma [9]. The purpose of this epidemiologic study is to investigate the injury pattern, severity, and mortality of the elderly patients treated for injuries sustained in motorcycle accidents in a level I trauma center in southern Taiwan using data from a population-based trauma registry.

Methods

Study design

The study was conducted at Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, a 2400-bed facility and a Level I regional trauma center that provides care to trauma patients primarily from South Taiwan. Approval for this study was obtained by the hospital institutional review board (approval number 103-2571B) before its initiation. This retrospective study was designed to review all the data added to the Trauma Registry System from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2013 for selection of cases that met the inclusion criteria of (1) age ≥ 65 years and (2) hospitalization for treatment of trauma sustained in a motorcycle accident. For comparison, data regarding adults aged 20–64 years old were also collected.

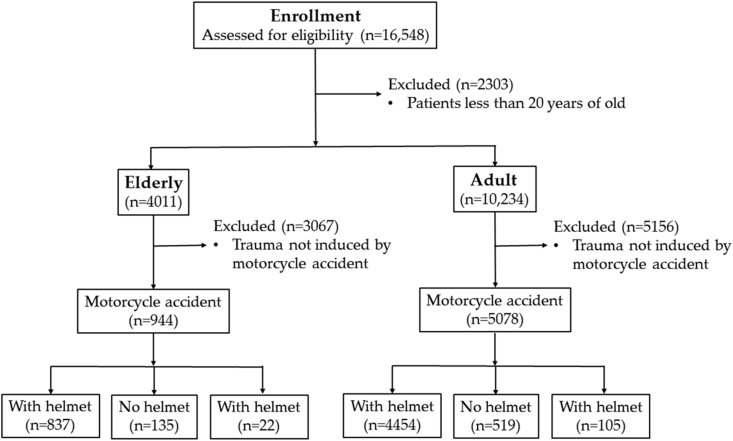

Among the 16,548 hospitalized registered patients entered in the database, 4011 (24.2%) were ≥65 years of age (hereafter referred to as elderly) and 10,234 (61.8%) were 20–64 years of old (hereafter referred to as adults). Among them, 994 (24.8%) elderly and 5078 (49.6%) adults had been admitted due to a motorcycle accident [Fig. 1]. Detailed patient information was retrieved from the Trauma Registry System of our institution and included data regarding age, sex, admission vital signs, injury mechanism, helmet use, the first Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) in the emergency department, Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) of each body region, Injury Severity Score (ISS), New Injury Severity Score (NISS), Trauma-Injury Severity Score (TRISS), length of hospital stay (LOS), length of intensive care unit stay (LICUS), in-hospital mortality, and associated complications. The data collected regarding the combined population of drivers and passengers (hereafter referred to as riders) were compared using SPSS v.20 statistical software (IBM, Armonk, NY) for performance of Pearson's chi-squared test, Fisher's exact test, or the independent student's t test, as applicable. All results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of studied groups of patients.

Results

Patient characteristics

The mean age was 75.9 ± 7.2 and 42.8 ± 13.4 years, respectively, in the elderly and adult patient groups [Table 1]. Statistically significant difference was found between the groups regarding sex. More female were found in the elderly patients. Of the 4011 elderly patients, 1687 (42.1%) were male and 2324 (57.9%), female. Of the 10,234 adult patients, 6487 (63.3%) were male and 3753 (36.7%) were female. In the elderly patients, fall presented the major mechanism for admission (59.9%), followed by motorcycle accident (24.8%) and bicycle accident (6.1%). Only 35 (0.9%) of the elderly patients had been riders in an automobile. In contrast, most of the injured adult patients were motorcycle riders, with 4831 (47.24%) adult drivers and 247 (2.4%) adult passengers.

Table 1.

Demographics of hospitalized trauma patients of the elderly and the adults.

| Variable | Elderly N = 4011 | Adult N = 10,234 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 75.9 ± 7.2 | 42.8 ± 13.4 | <0.001 |

| Gender, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 1687 (42.1) | 6481 (63.3) | |

| Female | 2324 (57.9) | 3753 (36.7) | |

| Mechanism, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Driver of MV | 24 (0.6) | 207 (2.0) | |

| Passenger of MV | 11 (0.3) | 102 (1.0) | |

| Driver of Motorcycle | 937 (23.4) | 4831 (47.2) | |

| Passenger of Motorcycle | 57 (1.4) | 247 (2.4) | |

| Bicycle | 245 (6.1) | 278 (2.7) | |

| Pedestrian | 122 (3.0) | 149 (1.5) | |

| Fall | 2403 (59.9) | 1909 (18.7) | |

| Unspecific | 212 (5.2) | 2511 (24.6) | |

| Time, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 7:00–17:00 | 2421 (60.4) | 5683 (55.5) | |

| 17:00–23:00 | 894 (22.3) | 2900 (28.3) | |

| 23:00–7:00 | 685 (17.1) | 1646 (16.1) | |

| Unspecific | 11 (0.3) | 5 (0.1) | |

| ISS | 9.6 ± 6.1 | 8.1 ± 7.3 | <0.001 |

| ISS | 0.014 | ||

| <16 | 3404 (84.9) | 8832 (86.3) | 0.027 |

| 16–24 | 446 (11.1) | 972 (9.5) | 0.004 |

| ≥25 | 161 (4.0) | 430 (4.2) | 0.613 |

| NISS | 10.8 ± 8.2 | 9.4 ± 8.9 | <0.001 |

| TRISS | 0.98 ± 0.16 | 0.99 ± 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 132 (3.3) | 145 (1.4) | <0.001 |

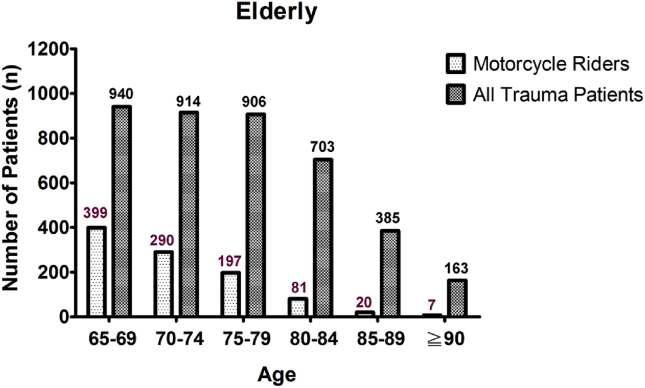

The data regarding the 994 (24.8%) elderly and 5078 (49.6%) adult patients who had been motorcycle riders were further compared for identification of differences regarding motorcycle-related major trauma injury. As shown in Fig. 2, of the 940, 914, 906, 703, 385, and 163 hospitalized patients aged 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85–89, and ≥90 years, respectively, 399, 290, 197, 81, 20, and 7 patients, respectively, had been admitted for treatment subsequent to a motorcycle accident. Among these elderly motorcycle riders, 89.1% (n = 886) were aged less than 80 years. Comparison of trauma injury scores for the elderly and adult groups indicated significant difference regarding ISS (9.6 ± 6.1 vs. 8.1 ± 7.3, respectively, p < 0.001). Significant difference (p = 0.014) was found between the elderly and adult patients regarding distribution of patients at different levels of injury severity (ISS < 16, 16–24, or ≥25). There were significant less elderly patients in the subgroup of ISS <16 (84.9% vs. 86.3%, respectively, p = 0.027) and more elderly patients in the subgroup of ISS between 16 and 24 (11.1% vs. 9.5%, respectively, p = 0.004) in comparison with those of adult patients. In addition, the motorcycle-related elderly trauma patients had higher injury severity regarding NISS (10.8 ± 8.2 vs. 9.4 ± 8.9, respectively, p < 0.001), TRISS (0.98 ± 0.16 vs. 0.99 ± 0.12, respectively, p < 0.001), and in-hospital mortality (3.3% vs. 1.4%, respectively, p < 0.001) than those adult motorcycle riders.

Fig. 2.

Number of elderly patients admitted for treatment of all trauma injury and number admitted for treatment of motorcycle-related trauma injury.

As shown in Table 2, of the 994 elderly and 5078 adult motorcycle riders, the mean age was 72.1 ± 5.5 and 40.9 ± 14.0 years, respectively. No statistically significant difference was found regarding sex was found between the elderly motorcycle riders, of whom 578 (58.1%) were male and 416 (41.9%) female, and the adult motorcycle riders, of whom 2897 (57.1%) were male and 2181 (42.9%) female. Analysis of the data regarding helmet-wearing status, which were recorded for 97.8% of the elderly and 98.0% of the adult patients, revealed that significantly more elderly motorcycle drivers had not been wearing a helmet compared to the adult motorcycle drivers (12.6% vs. 9.6%, respectively, p = 0.003). In contrast, no significant difference regarding helmet-wearing status was found between the elderly and adult motorcycle passengers.

Table 2.

Injury characteristics of the elderly and adult motorcycle riders.

| Motorcycle accident | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Elderly N = 994 | Adult N = 5078 | p |

| Age | 72.1 ± 5.5 | 40.9 ± 14.0 | <0.001 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.522 | ||

| Male | 578 (58.1) | 2897 (57.1) | |

| Female | 416 (41.9) | 2181 (42.9) | |

| Helmet wearing, n (%) | |||

| Drivers | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | 792 (79.7) | 4245 (83.6) | |

| No | 125 (12.6) | 487 (9.6) | |

| Passengers | 0.347 | ||

| Yes | 45 (4.5) | 209 (4.1) | |

| No | 10 (1.0) | 32 (0.6) | |

| Unknown | 22 (2.2) | 105 (2.0) | |

| GCS | 14.2 ± 2.5 | 14.2 ± 2.4 | 0.661 |

| GCS | 0.891 | ||

| ≤8 | 55 (5.5) | 296 (5.8) | |

| 9–12 | 42 (4.2) | 225 (4.4) | |

| ≥13 | 897 (90.3) | 4557 (89.7) | |

| AIS ≥3, n (%) | 0.006 | ||

| Head/Neck | 246 (24.7) | 970 (19.1) | <0.001 |

| Face | 1 (0.1) | 21 (0.4) | 0.159 |

| Thorax | 108 (10.9) | 443 (8.7) | 0.035 |

| Abdomen | 14 (1.4) | 130 (2.6) | 0.030 |

| Extremity | 302 (30.4) | 1109 (21.8) | <0.001 |

| ISS | 10.6 ± 8.2 | 9.3 ± 7.4 | 0.040 |

| ISS | 0.001 | ||

| <16 | 779 (78.4) | 4222 (83.1) | <0.001 |

| 16–24 | 155 (15.6) | 600 (11.8) | 0.001 |

| ≥25 | 60 (6.0) | 256 (5.1) | 0.197 |

| NISS | 12.4 ± 9.9 | 10.9 ± 9.0 | 0.045 |

| TRISS | 0.96 ± 0.20 | 0.99 ± 0.10 | <0.001 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 30 (3.0) | 76 (1.5) | 0.001 |

| LOS (days) | 11.1 ± 11.5 | 9.4 ± 10.1 | <0.001 |

| ICU | |||

| Patients, n (%) | 221 (22.2) | 898 (17.7) | 0.001 |

| <16 | 76 (9.8) | 315 (7.5) | 0.028 |

| 16–24 | 96 (61.9) | 370 (61.7) | 0.951 |

| ≥25 | 49 (81.7) | 213 (83.2) | 0.776 |

| LICUS (days) | 9.5 ± 12.7 | 7.0 ± 8.1 | <0.001 |

| <16 | 6.9 ± 9.0 | 4.9 ± 4.9 | <0.001 |

| 16–24 | 9.0 ± 10.6 | 6.3 ± 5.5 | <0.001 |

| ≥25 | 14.5 ± 18.9 | 11.2 ± 12.8 | 0.001 |

No significant difference was found between the elderly and adult patients regarding GCS score (14.2 ± 2.5 vs. 14.2 ± 2.4, respectively, p = 0.661) or distribution of patients at different levels of consciousness (p = 0.891). Analysis of AIS ≥3 revealed that the elderly patients had sustained significantly higher rates of head/neck (24.7% vs. 19.1%, respectively, p < 0.001), thorax injury (10.9% vs. 8.7%, respectively, p = 0.035), and extremity injury (30.4% vs. 21.8%, respectively, p < 0.001) than adult patients, while the adult patients had sustained higher significantly higher rates of abdomen injury (2.6% vs. 1.4%, respectively, p = 0.030). On the other hand, no significant differences regarding injury to the face region between the elderly and adult patients.

The elderly motorcycle riders have a higher severe injury score than the adult motorcycle riders (10.6 ± 8.2 vs. 9.6 ± 6.1, respectively, p < 0.001). Likewise, comparison of trauma injury scores for the elderly and adult motorcycle riders indicated significant difference regarding ISS (10.6 ± 8.2 vs. 9.3 ± 7.4, respectively, p = 0.040) and distribution of patients at different levels of injury severity (p = 0.001). There were significant less elderly patients in the subgroup of ISS <16 (78.49% vs. 83.1%, respectively, p < 0.001) and more elderly patients in the subgroup of ISS between 16 and 24 (15.6% vs. 11.8%, respectively, p = 0.001) in comparison with those of adult patients. There were also significant difference regarding NISS (12.4 ± 9.9 vs. 10.9 ± 9.0, respectively, p = 0.045), TRISS (0.96 ± 0.20 vs. 0.99 ± 0.10, respectively, p < 0.001), and in-hospital mortality (3.0% vs. 1.5%, respectively, p = 0.001) in these two groups of patients. Significant differences were found between the elderly and adult motorcycle riders regarding hospital LOS (11.1 days vs. 9.4 days, respectively, p < 0.001), proportion of patients admitted to the ICU (22.2% vs. 17.7%, respectively, p = 0.001), or LICUS (9.5 days vs. 7.0 days, respectively, p < 0.001). More elderly patients with ISS <16 (22.2% vs. 17.7%, respectively, p = 0.001) had been admitted into the ICU and the elderly patients had a longer LICUS in either subgroup of injury severity (<16, 16–24, ≥25).

Table 3 shows the findings regarding injury associated with motorcycle accidents. As can be observed, a significantly higher percentage of elderly motorcycle riders had sustained subdural hematoma (14.8% vs. 9.7%, respectively, p < 0.001), rib fracture (17.7% vs. 11.7%, respectively, p < 0.001), urinary bladder injury (0.5% vs. 0.2%, respectively, p = 0.031), femoral fracture (16.0% vs. 9.0%, respectively, p < 0.001), tibia fracture (12.9% vs. 10.7%, respectively, p = 0.041), and fibular fracture (9.6% vs. 5.3%, respectively, p < 0.001) but a significantly a lower percentage sustained neurologic deficit (0.3% vs. 1.0%, respectively, p = 0.028), cranial fracture (3.9% vs. 8.6%, respectively, p < 0.001), epidural hematoma (2.6% vs. 5.4%, respectively, p < 0.001), maxillary fracture (6.4% vs. 10.7%, respectively, p < 0.001), mandibular fracture (0.5% vs. 3.8%, respectively, p < 0.001), orbital fracture (092% vs. 3.0%, respectively, p < 0.001), nasal fracture (0.6% vs. 1.6%, respectively, p = 0.013), hepatic injury (0.3% vs. 2.8%, respectively, p < 0.001), splenic injury (0.3% vs. 1.5%, respectively, p = 0.002), and clavicle fracture (10.1% vs. 15.0%, respectively, p < 0.001) than adult motorcycle riders.

Table 3.

Associated injuries of the hospitalized elderly and adult motorcycle riders.

| Motorcycle accident | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Elderly N = 994 | Adult N = 5078 | p |

| Head trauma, n (%) | |||

| Neurologic deficit+ | 3 (0.3) | 52 (1.0) | 0.028 |

| Cranial fracture+ | 39 (3.9) | 437 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| Epidural hematoma (EDH)+ | 26 (2.6) | 272 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Subdural hematoma (SDH)* | 147 (14.8) | 492 (9.7) | <0.001 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) | 125 (12.6) | 583 (11.5) | 0.325 |

| Intracerebral hematoma (ICH) | 28 (2.8) | 122 (2.4) | 0.441 |

| Cerebral contusion | 66 (6.6) | 305 (6.0) | 0.446 |

| Cervical vertebral fracture | 4 (0.4) | 49 (1.0) | 0.081 |

| Maxillofacial trauma, n (%) | |||

| Maxillary fracture+ | 64 (6.4) | 543 (10.7) | <0.001 |

| Mandibular fracture+ | 5 (0.5) | 192 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Orbital fracture+ | 9 (0.9) | 151 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Nasal fracture+ | 6 (0.6) | 83 (1.6) | 0.013 |

| Thoracic trauma, n (%) | |||

| Rib fracture* | 176 (17.7) | 596 (11.7) | <0.001 |

| Sternal fracture | 2 (0.2) | 6 (0.1) | 0.509 |

| Hemothorax | 24 (2.4) | 104 (2.0) | 0.462 |

| Pneumothorax | 21 (2.1) | 103 (2.0) | 0.864 |

| Lung contusion | 9 (0.9) | 82 (1.6) | 0.092 |

| Hemopneumothorax | 18 (1.8) | 83 (1.6) | 0.691 |

| Thoracic vertebral fracture | 9 (0.9) | 39 (0.8) | 0.655 |

| Abdominal trauma, n (%) | |||

| Intra-abdominal injury | 9 (0.9) | 75 (1.5) | 0.158 |

| Hepatic injury+ | 3 (0.3) | 140 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| Splenic injury+ | 3 (0.3) | 77 (1.5) | 0.002 |

| Retroperitoneal injury | 2 (0.2) | 10 (0.2) | 0.978 |

| Renal injury | 4 (0.4) | 34 (0.7) | 0.329 |

| Urinary bladder injury* | 5 (0.5) | 8 (0.2) | 0.031 |

| Lumbar vertebral fracture | 18 (1.8) | 58 (1.1) | 0.083 |

| Sacral vertebral fracture | 2 (0.2) | 30 (0.6) | 0.121 |

| Extremity trauma, n (%) | |||

| Scapular fracture | 32 (3.2) | 127 (2.5) | 0.195 |

| Clavicle fracture+ | 100 (10.1) | 761 (15.0) | <0.001 |

| Humeral fracture | 59 (5.9) | 282 (5.6) | 0.632 |

| Radial fracture | 89 (9.0) | 559 (11.0) | 0.055 |

| Ulnar fracture | 43 (4.3) | 276 (5.4) | 0.152 |

| Femoral fracture* | 159 (16.0) | 456 (9.0) | <0.001 |

| Patella fracture | 24 (2.4) | 143 (2.8) | 0.479 |

| Tibia fracture* | 128 (12.9) | 241 (10.7) | 0.041 |

| Fibular fracture* | 95 (9.6) | 271 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| Metacarpal fracture | 34 (3.4) | 192 (3.8) | 0.583 |

| Metatarsal fracture | 29 (2.9) | 126 (2.5) | 0.425 |

| Calcaneal fracture | 65 (6.5) | 273 (5.4) | 0.144 |

| Pelvic fracture | 36 (3.6) | 176 (3.5) | 0.807 |

+ and ∗ indicated significant lower and higher incidences of the associated injury, respectively, in elderly motorcycle riders than those adult patients (p < 0.05).

Table 4 shows the results of analysis of helmet-wearing status among elderly riders. As can be observed, elderly riders who had not worn a helmet presented with a significantly lower first GCS score (13.4 ± 3.5 vs. 14.4 ± 2.1, respectively, p < 0.001) and distribution of patients at different levels of consciousness (p < 0.001) compared to those who had worn a helmet. A significantly greater percentage of elderly riders who had not worn a helmet presented with unconscious status as assessed by GCS score ≤8 (11.9% vs. 3.8%, respectively, p < 0.001), more head/neck injury (47.4% vs. 20.2%, respectively, p < 0.001) based on AIS ≥3, while a significantly lower percentage presented with extremity injury (20.7% vs. 32.1%, respectively, p = 0.009). A significantly greater percentage of elderly riders who had not worn a helmet presented with more subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and cerebral contusion. In contrast, no significant differences were found between elderly riders who had and had not worn a helmet regarding incidence of maxillofacial trauma, regardless of the type of trauma (maxillary fracture, mandibular fracture, orbital fracture, or nasal fracture). The elderly patients who had not worn a helmet had sustained more severe injury regarding ISS (13.5 ± 8.7 vs. 9.8 ± 7.2, respectively, p < 0.001) and distribution of patients at different levels of injury severity (p < 0.001) than those who had worn a helmet. While significantly more patients who had not worn a helmet had sustained severe injury (ISS 16–24; 29.6% vs. 13.3%, respectively, p < 0.001, and ISS≥25; 12.6% vs. 4.3%, respectively, p < 0.001), significantly fewer patients who had not worn a helmet had an ISS less than 16 (57.8% vs. 82.4%, respectively, p < 0.001). In those elderly riders who had not worn a helmet, there were significant higher NISS (15.8 ± 11.1 vs. 11.5 ± 8.9, respectively, p < 0.001), lower TRISS (0.88 ± 0.20 vs. 0.94 ± 0.12, respectively, p < 0.001), and higher in-hospital mortality (5.9% vs. 1.9%, respectively, p = 0.005) when compared to those had worn a helmet in the motorcycle accident. Significant differences were also found between the elderly riders with or without helmet-wearing regarding hospital LOS (10.8 days vs. 12.2 days, respectively, p = 0.019) and proportion of patients admitted to the ICU (19.4% vs. 34.1%, respectively, p < 0.001), but not LICUS (9.2 days vs. 10.3 days, respectively, p = 0.188).

Table 4.

Injury characteristics of the elderly motorcycle riders according to helmet-wearing status.

| Motorcycle accident (Elderly) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Helmet+ N = 837 |

Helmet− N = 135 |

p | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.299 | ||

| Male | 481 (57.5) | 84 (62.2) | |

| Female | 356 (42.5) | 51 (37.8) | |

| GCS | 14.4 ± 2.1 | 13.4 ± 3.5 | <0.001 |

| GCS | <0.001 | ||

| ≤8 | 32 (3.8) | 16 (11.9) | <0.001 |

| 9–12 | 30 (3.6) | 8 (5.9) | 0.426 |

| ≥13 | 775 (92.6) | 111 (82.2) | 0.327 |

| AIS ≥3, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Head/Neck | 169 (20.2) | 64 (47.4) | <0.001 |

| Face | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Thorax | 85 (10.2) | 19 (14.1) | 0.177 |

| Abdomen | 11 (1.3) | 3 (2.2) | 0.428 |

| Extremity | 269 (32.1) | 28 (20.7) | 0.009 |

| Head trauma, n (%) | |||

| Neurologic deficit | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.486 |

| Cranial fracture | 30 (3.6) | 7 (5.2) | 0.367 |

| Epidural hematoma (EDH) | 19 (2.3) | 6 (4.4) | 0.139 |

| Subdural hematoma (SDH)* | 93 (11.1) | 43 (31.9) | <0.001 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)* | 82 (9.8) | 30 (22.2) | <0.001 |

| Intracerebral hematoma (ICH) | 20 (2.4) | 7 (5.2) | 0.067 |

| Cerebral contusion* | 40 (4.8) | 21 (15.6) | <0.001 |

| Cervical vertebral fracture | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0.520 |

| Maxillofacial trauma, n (%) | |||

| Maxillary fracture | 53 (6.3) | 10 (7.4) | 0.638 |

| Mandibular fracture* | 3 (0.4) | 2 (1.5) | 0.091 |

| Orbital fracture | 8 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.254 |

| Nasal fracture | 6 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.324 |

| ISS | 9.8 ± 7.2 | 13.5 ± 8.7 | <0.001 |

| ISS | <0.001 | ||

| <16 | 690 (82.4) | 78 (57.8) | <0.001 |

| 16–24 | 111 (13.3) | 40 (29.6) | <0.001 |

| ≥25 | 36 (4.3) | 17 (12.6) | <0.001 |

| NISS | 11.5 ± 8.9 | 15.8 ± 11.1 | <0.001 |

| TRISS | 0.94 ± 0.12 | 0.88 ± 0.20 | <0.001 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 16 (1.9%) | 8 (5.9%) | 0.005 |

| LOS (days) | 10.8 ± 11.0 | 12.2 ± 13.3 | 0.019 |

| ICU | |||

| Patients, n (%) | 162 (19.4) | 46 (34.1) | <0.001 |

| LIS (days) | 9.2 ± 12.3 | 10.3 ± 14.6 | 0.188 |

∗ indicated significant higher incidence of the associated injury in elderly motorcycle riders without helmet-wearing than those patients with helmet-wearing (p < 0.05).

Additionally, Table 5 shows the results of analysis of helmet-wearing status among adult riders. As can be observed, adult riders who had not worn a helmet presented with a significantly lower first GCS score (12.5 ± 3.9 vs. 14.4 ± 2.0, respectively, p < 0.001) and had a significant distribution of patients in different level of consciousness (p < 0.001) compared to those who had worn a helmet. A significantly greater percentage of adult riders who had not worn a helmet presented with unconscious status as assessed by GCS score ≤8 (19.1% vs. 3.7%, respectively, p < 0.001) or between 9 and 12 (11.4% vs. 3.4%, respectively, p < 0.001), more head/neck injury (45.5% vs. 15.3%, respectively, p < 0.001) and face injury (1.2% vs. 0.3%, respectively, p = 0.017) based on AIS ≥3, while a significantly lower percentage presented with extremity injury (13.7% vs. 23.1%, respectively, p < 0.001). A significantly greater percentage of adult riders who had not worn a helmet presented with more cranial fracture, epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral contusion, maxillary fracture, and nasal fracture. In contrast, no significant differences were found between adult riders who had and had not worn a helmet regarding incidence of mandibular fracture and orbital fracture. The adult patients who had not worn a helmet had sustained more severe injury regarding ISS (13.0 ± 9.4 vs. 8.7 ± 6.7, respectively, p < 0.001) and distribution of patients at different levels of injury severity (p < 0.001) than those who had worn a helmet. While significantly more patients who had not worn a helmet had sustained severe injury (ISS 16–24; 25.2% vs. 10.0%, respectively, p < 0.001, and ISS ≥25; 12.5% vs. 3.8%, respectively, p < 0.001), significantly fewer patients who had not worn a helmet had an ISS less than 16 (62.2% vs. 86.2%, respectively, p < 0.001). In those adult riders who had not worn a helmet, there were significant higher NISS (15.9 ± 12.5 vs. 10.1 ± 8.0, respectively, p < 0.001), lower TRISS (0.93 ± 0.17 vs. 0.97 ± 0.08, respectively, p < 0.001), and higher in-hospital mortality (4.0% vs. 0.8%, respectively, p < 0.001) when compared to those had worn a helmet in the motorcycle accident. Significant differences were also found between the adult riders with or without helmet-wearing regarding hospital LOS (9.0 days vs. 12.0 days, respectively, p < 0.001) and proportion of patients admitted to the ICU (14.7% vs. 37.6%, respectively, p < 0.001), but not LICUS (6.6 days vs. 7.5 days, respectively, p = 0.173).

Table 5.

Injury characteristics of the adult motorcycle riders according to helmet-wearing status.

| Motorcycle accident (Adult) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Helmet+ N = 4454 |

Helmet− N = 519 |

p | |

| Gender, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 2461 (55.3) | 365 (70.3) | |

| Female | 1993 (44.7) | 154 (29.7) | |

| GCS | 14.4 ± 2.0 | 12.5 ± 3.9 | <0.001 |

| GCS | <0.001 | ||

| ≤8 | 167 (3.7) | 99 (19.1) | <0.001 |

| 9–12 | 153 (3.4) | 59 (11.4) | <0.001 |

| ≥13 | 4134 (92.8) | 361 (69.6) | <0.001 |

| AIS ≥3, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Head/Neck | 682 (15.3) | 236 (45.5) | <0.001 |

| Face | 15 (0.3) | 6 (1.2) | 0.017 |

| Thorax | 371 (8.3) | 56 (10.8) | 0.068 |

| Abdomen | 114 (2.6) | 13 (2.5) | 1.000 |

| Extremity | 1027 (23.1) | 71 (13.7) | <0.001 |

| Head trauma, n (%) | |||

| Neurologic deficit | 41 (0.9) | 10 (1.9) | 0.039 |

| Cranial fracture* | 281 (6.3) | 131 (25.2) | <0.001 |

| Epidural hematoma (EDH)* | 168 (3.8) | 87 (16.8) | <0.001 |

| Subdural hematoma (SDH)* | 319 (7.2) | 146 (28.1) | <0.001 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)* | 420 (9.4) | 134 (25.8) | <0.001 |

| Intracerebral hematoma (ICH)* | 84 (1.9) | 29 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Cerebral contusion* | 212 (4.8) | 74 (14.3) | <0.001 |

| Cervical vertebral fracture | 39 (0.9) | 9 (1.7) | 0.090 |

| Maxillofacial trauma, n (%) | |||

| Maxillary fracture* | 445 (10.0) | 82 (15.8) | <0.001 |

| Mandibular fracture | 160 (3.6) | 25 (4.8) | 0.176 |

| Orbital fracture | 125 (2.8) | 20 (3.9) | 0.213 |

| Nasal fracture* | 63 (1.4) | 16 (3.1) | 0.007 |

| ISS | 8.7 ± 6.7 | 13.0 ± 9.4 | <0.001 |

| ISS | <0.001 | ||

| <16 | 3841 (86.2) | 323 (62.2) | <0.001 |

| 16–24 | 444 (10.0) | 131 (25.2) | <0.001 |

| ≥25 | 169 (3.8) | 65 (12.5) | <0.001 |

| NISS | 10.1 ± 8.0 | 15.9 ± 12.5 | <0.001 |

| TRISS | 0.973 ± 0.084 | 0.927 ± 0.166 | <0.001 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 37 (0.8) | 21 (4.0) | <0.001 |

| LOS (days) | 9.0 ± 9.2 | 12.0 ± 12.6 | <0.001 |

| ICU | |||

| Patients, n (%) | 656 (14.7) | 195 (37.6) | <0.001 |

| LIS (days) | 6.6 ± 7.7 | 7.5 ± 7.9 | 0.173 |

* indicated significant higher incidence of the associated injury in elderly motorcycle riders without helmet-wearing than those patients with helmet-wearing (p < 0.05).

Discussion

This study analyzed the demographics and characteristics of injuries observed in a geriatric population with motorcycle-related injuries presenting at a level I trauma center. Analysis of the data indicates that elderly motorcycle riders have a higher severe injury score, present with a different bodily injury pattern, and have worse outcome and higher mortality than those adult motorcycle riders. It also revealed that a significant percentage of elderly motorcycle riders do not wear a helmet, which puts them at high risk of injury with worse outcome.

In the current study, compared to adult patients, there were significant less elderly patients in the subgroup of ISS <16 and more elderly patients in the subgroup of ISS between 16 and 24. In these two groups of patients, there were also significant difference regarding NISS, TRISS, in-hospital mortality, hospital LOS, proportion of patients admitted to the ICU, and longer ICU stay. These results of the motorcycle-related trauma in the elderly are generally in agreement with the reports of literature that higher injury severity, less favorable outcomes, prolonged hospital stays, and higher mortality in the elderly trauma patients [6], [10]. Although some reports had indicated that the severe injury rate in the elderly was almost 5 times greater than in adults [2] and there was an overall mortality rate of 14.8% in a meta-analysis of 65,897 pooled geriatric trauma patients [10], we did not found such obvious difference in injury severity and mortality in the motorcycle-related elderly patients in this study. Considering that almost all of motorcycles are forbidden on highways in Asian cities and that most traffic accidents occur in relatively crowded streets in these cities, we hypothesize that the reason for the discrepancy between our findings and those of prior studies is that most motorcycle injuries in the Asian region occur at relatively low velocity. In addition, different trauma mechanism as there are less motorcycles used in the racing, recreation, and off-road use in the Asian cities may also contribute the discrepancy of the reported mortality.

Based on analysis of AIS, the elderly motorcycle riders were found to have presented with a different bodily injury pattern compared to the adult motorcycle riders. Elderly drivers were found to have a higher incidence of potentially fatal injuries such as intracranial hemorrhage and chest injuries when compared with younger individuals [6]. In this study, the elderly motorcycle riders presented with a higher rate of injury to the head/neck, thorax, and extremity region but less to the abdomen area based on AIS ≥3, and a higher rate of subdural hematoma, rib fracture, urinary bladder injury, femoral fracture, tibia fracture, and fibular fracture. In elderly motorcycle riders, a higher rate of injury to the thorax was associated with a higher incidence of rib fracture. Notably, the elderly motorcycle riders sustained a greater incidence of urinary bladder injury than adult motorcycle riders, whereas the latter sustained a significantly higher rate of injuries around the abdomen. Although urinary bladder injury is reported to be associated with a concomitant pelvic fracture, in such condition the blunt force trauma also place the bladder and urethra at risk for injury [11], [12], there was no significant difference regarding pelvic fracture in the elderly and adult motorcycle riders (3.6% vs. 3.5%, respectively, p = 0.807) in this study [Table 3]. The reason that the adult motorcyclists had a significantly higher rate of abdominal injury in this study is unknown, although we had suspected there may exist a higher impact of handle bar collision of these adult motorcyclists who may drive faster and more recklessly than older motorcyclists [13]; however, further analysis is not possible due to insufficient documentation of the circumstances of injury events and a lack of applicable emergency codes specific for handle bar injury [14]. Addition, with a higher rate of injury to extremity, the elderly motorcycle riders also sustained a greater incidence of bone fractures in the lower extremities than adult motorcycle riders.

In Taiwan, motorcyclist fatality accounts for nearly 60% of all driving fatalities in the country [15]. Analysis of the collected data revealed an association between higher fatality rates and the factors of male sex, advanced age, unlicensed status, not wearing a helmet, riding after alcohol consumption, and alcohol consumption of more than 550 cc [15]. In this current study, 30 of 132 (22.7%) fatalities among the elderly and 76 of 145 (52.4%) among adults were found to have involved motorcycle use; however, there was twice in-hospital mortality of the elderly motorcyclists than the adult motorcyclists (3.0% vs. 1.5%, respectively, p = 0.001), which reflect the vulnerability of the elderly motorcyclist and the importance of the protection intervention. Among several preventive measures, helmet wearing in particular has been shown to protect against head and other serious injuries and to be cost effective [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. Recent studies have shown that helmets reduce head injury rates by up to 72 per cent in motorcycle trauma [21], [22], [23]. In the current study, elderly motorcycle drivers, but not passengers, were found less likely to wear a helmet than adult motorcycle drivers. In the elderly motorcyclists, compared to patients who had worn a helmet, patients who had not worn a helmet had a lower first GCS score, and a greater percentage presented with unconscious status (GCS score ≤8); had sustained subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral contusion, and severe injury (ISS 16–24 and ≥25); had longer hospital stay and higher mortality; and had required admission to the ICU. In the adult motorcyclists, the results are similar to those in the elderly motorcyclists. Compared to patients who had worn a helmet, patients who had not worn a helmet had a lower first GCS score, and a greater percentage presented with a GCS score ≤8 or between 9 and 12; had sustained epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hematoma, cerebral contusion, and severe injury (ISS 16–24 and ≥25); had longer hospital stay and higher mortality; and had required admission to the ICU. These findings indicate that wearing a helmet may prevent head injury and reduce injury severity among both elderly and adult motorcycle riders.

The limitations of this study include the use of a retrospective design and the lack of availability of data regarding the circumstances of the mechanism of injury. Lack of data regarding the motorcycle speed during accidents, the type of motorcycle, type of helmet material, and the use of any other protective materials, such as knee braces, prevented analysis of motorcycle-related hospitalization based on exposure-based risk. Furthermore, the use of psychoactive drugs or alcohol was not identified and analyzed and may be a confound factor. In addition, the impact of preexisting comorbidities in the elderly on the hospitalization course and on the mortality remained unclarified.

Conclusion

Elderly motorcycle riders tends to present with a higher injury severity compared to adult patients and a bodily injury pattern differing from that of adult motorcycle riders, indicating the need to emphasize the use of protective equipment, especially helmets, to reduce their rate of trauma to head and maxillary regions and the severity of injury.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant CDRPG8C0033 from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Brown J.B., Bankey P.E., Gorczyca J.T., Cheng J.D., Stassen N.A., Gestring M.L. The aging road warrior: national trend toward older riders impacts outcome after motorcycle injury. Am Surg. 2010;76:279–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciesla D.J., Pracht E.E., Tepas J.J., 3rd, Cha J.Y., Langland-Orban B., Flint L.M. The injured elderly: a rising tide. Surgery. 2013;154:291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandya S.R., Yelon J.A., Sullivan T.S., Risucci D.A. Geriatric motor vehicle collision survival: the role of institutional trauma volume. J Trauma. 2011;70:1326–1330. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820e327c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caterino J.M., Valasek T., Werman H.A. Identification of an age cutoff for increased mortality in patients with elderly trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Min L., Ubhayakar N., Saliba D., Kelley-Quon L., Morley E., Hiatt J. The vulnerable elders survey-13 predicts hospital complications and mortality in older adults with traumatic injury: a pilot study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1471–1476. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cevik Y., Dogan N.O., Das M., Karakayali O., Delice O., Kavalci C. Evaluation of geriatric patients with trauma scores after motor vehicle trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:1453–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss H., Agimi Y., Steiner C. Youth motorcycle-related brain injury by state helmet law type: United States, 2005–2007. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1149–1155. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talving P., Teixeira P.G., Barmparas G., Dubose J., Preston C., Inaba K. Motorcycle-related injuries: effect of age on type and severity of injuries and mortality. J Trauma. 2010;68:441–446. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181cbf303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers S.C., Campbell B.T., Saleheen H., Borrup K., Lapidus G. Using trauma registry data to guide injury prevention program activities. J Trauma. 2010;69:S209–S213. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f1e9fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashmi A., Ibrahim-Zada I., Rhee P., Aziz H., Fain M.J., Friese R.S. Predictors of mortality in geriatric trauma patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:894–901. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182ab0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjurlin M.A., Fantus R.J., Mellett M.M., Goble S.M. Genitourinary injuries in pelvic fracture morbidity and mortality using the National Trauma Data Bank. J Trauma. 2009;67:1033–1039. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181bb8d6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durrant J.J., Ramasamy A., Salmon M.S., Watkin N., Sargeant I. Pelvic fracture-related urethral and bladder injury. J R Army Med Corps. 2013;159:i32–i39. doi: 10.1136/jramc-2013-000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith B.W., Buyea C.M., Anders M.J. Incidence and injury types in motorcycle collisions involving deer in Western New York. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead, NJ) 2015;44:E180–E183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mezhir J.J., Glynn L., Liu D.C., Statter M.B. Handlebar injuries in children: should we raise the bar of suspicion? Am Surg. 2007;73:807–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jou R.C., Yeh T.H., Chen R.S. Risk factors in motorcyclist fatalities in Taiwan. Traffic Inj Prev. 2012;13:155–162. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2011.641166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hundley J.C., Kilgo P.D., Miller P.R., Chang M.C., Hensberry R.A., Meredith J.W. Non-helmeted motorcyclists: a burden to society? A study using the National Trauma Data Bank. J Trauma. 2004;57:944–949. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000149497.20065.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacLeod J.B., Digiacomo J.C., Tinkoff G. An evidence-based review: helmet efficacy to reduce head injury and mortality in motorcycle crashes: EAST practice management guidelines. J Trauma. 2010;69:1101–1111. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f8a9cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider WHt, Savolainen P.T., Van Boxel D., Beverley R. Examination of factors determining fault in two-vehicle motorcycle crashes. Accid Anal Prev. 2012;45:669–676. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2011.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heldt K.A., Renner C.H., Boarini D.J., Swegle J.R. Costs associated with helmet use in motorcycle crashes: the cost of not wearing a helmet. Traffic Inj Prev. 2012;13:144–149. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2011.637252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung S., Xiao Q., Yoon Y. Evaluation of motorcycle safety strategies using the severity of injuries. Accid Anal Prev. 2013;59:357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2013.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ooi S.S., Wong S.V., Yeap J.S., Umar R. Relationship between cervical spine injury and helmet use in motorcycle road crashes. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2011;23:608–619. doi: 10.1177/1010539511413750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dinh M.M., Curtis K., Ivers R. The effectiveness of helmets in reducing head injuries and hospital treatment costs: a multicentre study. Med J Aust. 2013;198:415–417. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Philip A.F., Fangman W., Liao J., Lilienthal M., Choi K. Helmets prevent motorcycle injuries with significant economic benefits. Traffic Inj Prev. 2013;14:496–500. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2012.727109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]