Abstract

Background

To recognize deaths in the otorhinolaryngology indoor wards, determine the reason behind the mortalities and recommend modifications for betterment of patient care and surgical outcomes.

Method

Data was collected from the mortality register, operation theatre registers, ward registers and case notes of patients declared dead at an urban tertiary health care center in India for a period of 5 years; from January 2012 to December 2016. The data included date of admission, age, sex, educational status, residence, and clinical diagnosis, course of hospital stay and medical cause of death. Data acquired was reviewed and statistically interpreted and presented in graphical and descriptive formats.

Results

6157 admissions were made in otorhinolaryngology (ENT) ward in the 5 year period which included 3969 males and 2188 female patients. 58 deaths were recorded during this period which gives overall death per admission crude mortality rate of 9.42% at an average of about 12 (11.60) deaths per year. The major causes of death were malignancy and septicemia.

Conclusion

The significance of health education, aggressive healthcare campaigns, enhancement of healthcare services and wide accessibility of healthcare services to remote areas has been emphasized. Role of structured study and protocols in the management of serious cases is highlighted along with the need for prompt referral and better interdepartmental cooperation.

Keywords: Mortality, Death, Otorhinolaryngology ward, Review, Audit, Pattern

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

A systemic scrutiny of mortality patterns divulges the quality of surgical care, viability of treatment methods and accessibility to ground healthcare resources in a community. Critical review of mortality pattern through audit or surveillance aids to improve patient care and facilitates implementation of trends that improve the mortality rate.

What this study adds to the field

This study aims to analyze the mortality patterns in otorhinolaryngology wards and implement the findings to lower the mortality rates. Results of the present study will aid in betterment of the quality of healthcare by enlightening the about avertable deaths and to recommend steps to strengthen healthcare infrastructure.

The domain of otorhinolaryngology has widened by leaps and bounds in previous few decades. The introduction of state of the art instrument and equipments has enabled otorhinolaryngologists to venture into untraded waters, fulfilling the idiom of “from dura to pleura” surgeons, and even beyond. This has led to a drastic alteration in standard and techniques of pre- and post-operative care in otorhinolaryngology indoor wards. Surgical care in wards is an integral protocol of patient management protocol with profound significance in altering the prognosis. Mortality is an inevitable complication of surgical care occurring owing to a multitude of factors. A scrupulous and systemic scrutiny of mortality patterns divulges the quality of surgical care, viability of treatment methods and accessibility to ground healthcare resources in a community. Critical review of mortality pattern through audit or surveillance aids to improve patient care and facilitates implementation of trends that improve the mortality rate in future. Audits in surgical wards from varied perspectives have been regularly carried out all over the globe [1], [2], [3]. Hence, in the context of changing scenario of otorhinolaryngology, it becomes imperative to evaluate mortality patterns in our wards. This retrospective study aims to plug this lacuna by analyzing the mortality patterns in otorhinolaryngology wards of a tertiary health care center in urban India and implement the findings to lower the mortality rates by appropriate interventions. Results of the present study will aid in betterment of the quality of healthcare by enlightening the health care professionals about avertable deaths and to recommend the administration for strengthening of healthcare infrastructure.

Materials and methods

This retrospective descriptive observational study was conducted at Patna Medical College and Hospital which is a tertiary care referral hospital cum teaching institute situated in the district of Patna, India. Records were collected from the mortality register of the otorhinolaryngology wards for a period of January 2012 to December 2016. This included the entire group of patient admitted in ENT ward that died in this period irrespective of whether surgery was conducted or not. Data included the demographics, age, gender, residence, date of admission, surgical diagnosis, course of hospital stay, comorbidities and clinical cause of death. The records collected were utilized to retrieve admission records and case notes from medical records department which were reviewed in totality. The admission register was used to pull together details of annual admissions during the study period. The data collected was statistically interpreted and presented in tabular and descriptive formats. Deaths in the ENT emergency which were not admitted in indoor wards were not included in the study. Case definition of in-hospital surgical mortality was taken as deaths occurring within 30 days of admission for surgical care which is the same as traditionally employed in other studies [4].

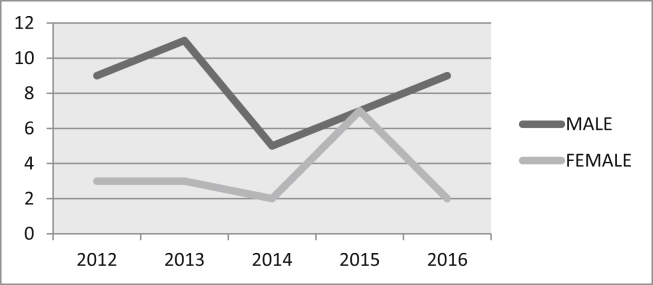

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel for entry of data and Epi Info software for statistical analysis [Fig. 1].

Fig. 1.

Gender and year wise distributions of death.

Results

6157 admissions were made in the otorhinolaryngology wards of Patna Medical College and Hospital, Patna from January 2012 to December 2016. This included 3969 males (64.46%) and 2188 female (35.53%) patients. 58 deaths were recorded among these patients in the same wards for the same duration. Of the 58 deaths, 41 (70.68%) were male and 17 (29.31%) were female patients in a ratio of 2.41:1 [Fig. 1]. Table 1 shows year wise mortality rate and Table 2 and Fig. 2 show gender specific mortality rate per year in the time period specified above.

Table 1.

Distribution of year wise mortality rate.

| Year | Admissions | Deaths | Mortality rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 1270 | 12 | 9.44 |

| 2013 | 1265 | 14 | 11.06 |

| 2014 | 1229 | 7 | 5.69 |

| 2015 | 1211 | 14 | 11.56 |

| 2016 | 1182 | 11 | 9.30 |

| Total | 6157 | 58 | 9.42 |

Table 2.

Gender specific mortality rates.

| Year | Admissions | Male Admissions | Male deaths | Gender Specific death rate (males) | Female admissions | Female deaths | Gender Specific death rate (females) | Deaths | Mortality rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 1270 | 832 | 9 | 10.81 | 438 | 3 | 6.84 | 12 | 9.44 |

| 2013 | 1265 | 839 | 11 | 13.11 | 426 | 3 | 7.04 | 14 | 11.06 |

| 2014 | 1229 | 797 | 5 | 6.27 | 432 | 2 | 4.62 | 7 | 5.69 |

| 2015 | 1211 | 747 | 7 | 9.37 | 464 | 7 | 15.08 | 14 | 11.56 |

| 2016 | 1182 | 754 | 9 | 11.93 | 428 | 2 | 4.67 | 11 | 9.30 |

| Total | 6157 | 3969 | 41 | 10.33 | 2188 | 17 | 7.76 | 58 | 9.42 |

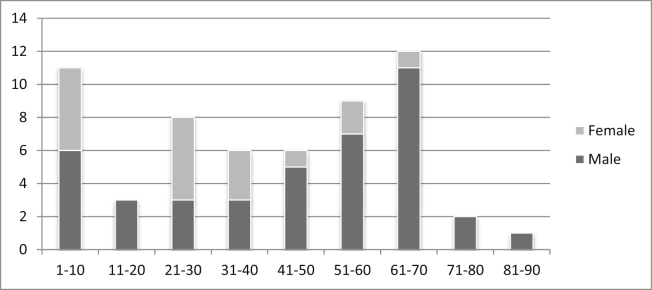

Fig. 2.

Proportional mortality rate by age during the period 2011–2015.

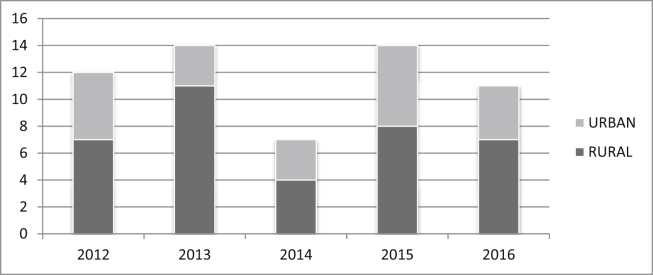

The mortality rate in different age group was also calculated and tabulated for mortalities occurring in ENT wards. The age of the deceased patients ranged from 14 months to 90 years with a median age of 40.60 years. Table 3 and Fig. 2 depict the year wise proportional mortality rate in different age group categorized according to the patient's gender. 37 patients (63.79%) of the patients belonged to the rural areas whereas the remaining 21 patients (36.20%) were urban dwellers. Fig. 3 illustrates the distribution pattern of residential addresses of the mortalities, segregating the addresses as rural and urban dwellings.

Table 3.

Proportional mortality rate by age during the period 2011–2015.

| Distribution of death (according to age in years) | Number of death during the period 2011–2015 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | Percentage | |

| 1–10 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 18.96 |

| 11–20 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 5.17 |

| 21–30 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 13.79 |

| 31–40 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 10.34 |

| 41–50 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 10.34 |

| 51–60 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 15.51 |

| 61–70 | 11 | 1 | 12 | 20.68 |

| 71–80 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3.44 |

| 81–90 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1.72 |

| Total | 41 | 17 | 58 | 100 |

Fig. 3.

Distribution pattern of residential address of mortalities.

The commonest cause of mortality in otorhinolaryngology wards was found out to be malignancy (32.75%), consisting of laryngeal, oropharyngeal, esophageal, sinonasal and temporal bone malignancy. Malignancy was followed by septicemia and cellulitis (20.68%) mainly due to oral and oropharyngeal abscess, Ludwig's angina and neck abscess. Other main causes were intracranial complications of chronic otitis media (12.06%) such as meningitis and intracranial abscess; epistaxis (10.34%) due to juvenile nasal angiofibroma and bleeding disorders; and foreign body aspiration or ingestion in aerodigestive track (10.34%). Relatively infrequent causes of deaths were neck trauma, cervical tuberculosis, road traffic accidents, renal failure, maggots and diabetic complications. Foreign body removal by bronchoscopy, esophagoscopy, tracheostomy, excision or biopsy of malignant tissues and repair of cut throat injury of the neck were of the main surgical interventions carried out in these patients. Table 4 tabulates the clinical conditions associated with mortalities in our study population.

Table 4.

Clinical conditions involved with mortalities in ENT ward.

| Clinical conditions | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Malignancy | 19 | 32.75 |

|

8 | |

|

2 | |

|

1 | |

|

2 | |

|

6 | |

| Septicemia/Cellulitis | 12 | 20.68 |

| Foreign body | 6 | 10.34 |

|

4 | |

|

2 | |

| COM Intracranial | 7 | 12.06 |

| Neck Trauma | 2 | 3.44 |

| Epistaxis(Bleeding disorder/JNA) | 6 | 10.34 |

| TB Cervical | 1 | 1.72 |

| Maggots | 1 | 1.72 |

| RTA | 2 | 3.44 |

| Renal Failure | 1 | 1.72 |

| Diabetic complications | 1 | 1.72 |

| Total | 58 | 100.0 |

Discussion

Death in a hospital is a catastrophic but inevitable part of patient care and management. The mortality rate of a health institution may be an indicator of its performance or a representation of the burden of fatal conditions that the institution is faced with [5]. Hospital mortalities often invite unnecessary public attentions, media scrutiny and administrative interference in healthcare. Also it adds to the occupational stress among surgeons [6]. It is therefore, of paramount significance to regularly review the mortality rate of a healthcare facility with the intention to implement apt modifications in the health delivery system to lower the rate [7].

The mortality rate in the otorhinolaryngology ward in our study is 9.42% of total admissions. While literature regarding studies of emergency admissions, types of cases and attributable deaths in the ENT emergency are available abundantly [7], [8], [9], data regarding mortality in ENT indoor wards is conspicuous by its absence. This makes the present study one of the first of its kind to address the issue of mortality auditing in the ENT wards in a tertiary health care set up. Similar audits in other specialties have taken place all over the globe. Published mortalities in similar retrospective studies by Anelechi et al. [10] and Ihegihu et al. [11] in surgical wards are 9.14% and 8.3% respectively. Comparison of mortality rate, specifically of the otorhinolaryngology ward of different health care setting would be a better index of the standard of the ENT health care provided at an institution.

The number of males in the mortality list far outnumbered the number of females in the same time period (10.33 vs. 7.69). This corroborated with the gender wise distribution of male admissions (3969) as compared with female admissions (2188). Traditionally men make up two thirds of the surgical patients compared to women [6]. Our study also projects comparable findings. Several studies in the surgical wards have revealed preponderance of male deaths to female deaths analogous to our study [10], [12]. The patriarchal social system which is still prevalent in the rural areas of the society in study describes the variation between male and female admission as well as mortality rate. This also underlines the need for more women centric health programs in the developing countries, especially in the rural areas. The age group of patients ranged from 14 months to 90 years of age with an increased cluster shown in the 7th decade of life. The incidence of malignancy and comorbidity related deaths showed a definite peak in older age group, agreeing with the progression pattern of the disease. Trauma related events were more frequent in adults whereas deaths due to foreign body obstructions and spread of infections such as complication of chronic otitis media and deep space infections of neck were characterized by their high prevalence in children. While deaths in young put an immense burden on the family and society, deaths in geriatric population tend to reflect the delay in diagnosis, lack of appropriate care and dearth of medical assistance to this group.

The clinical conditions which led to maximum mortality in our study was malignancy (32.75%), complications arising out of septicemia (20.68%), chronic otitis media (12.06), foreign body obstruction in pediatric population (10.34%) and injuries to the neck (3.44%). Malignancy related cases in old age group are often characterized by presentation in late stages, either owing to neglect by the patient or the family, decreased awareness or lack of proper care. Most of the deaths occurred in cases where progression of the disease has made the case surgically non salvageable in final stages. Post radiotherapy and post chemotherapy cases of malignancy with recurrence of the diseases were also frequently seen to contribute to mortality. The field of head and neck surgical oncology has made rapid strides in past few decades. Hence early detection, presentation and referral would go a long way in reducing mortality and morbidity in malignancy cases. Neglect by the family contributing to the increased mortality in this group has been cited in other studies [13]. Aspirated foreign bodies in the air passage present as a grave challenge to an otolaryngologists, requiring prompt action to prevent mortality [14]. Late presentation to tertiary health centers due to lack of facilities of bronchoscopy in primary level health centers and rural areas abet mortality in these cases. State of the art equipments and trained professional for performing bronchoscopy should be available at all centers exposed to these cases to assure timely interventions. Complications in chronic otitis media and septicemia such as Ludwig's angina, oro- and parapharyngeal abscesses often arise due to delayed treatment from ignorance, lack of health education, malnutrition, overcrowding and poverty. Deep neck space infections and chronic otitis media have been attributed to poor socio-economic conditions in multiple studies [15], [16]. The prevalence of infective etiologies leading to mortality is a grave but prominent indicator of the lack of health care in a developing country. The extensive spread of infection leading to septicemia before presentation to our health care centre was routinely seen. In spite of aggressive management in aseptic conditions with minimal possible hospital acquired infections, a number of these patients succumbed due to wide ranging septicemia. Our centre is a tertiary health care centre situated in the state capital which deals with all ENT emergency cases along with cases of head and neck malignancy cases from a very large catchment area of surrounding districts, some of which present in a very advanced stage.

The role of comorbidities in patients has been highlighted in several studies as it has noteworthy contribution to overall mortality rate, especially in the geriatric population. Semmens et al. found that 91% of patients who died in their study had significant comorbidities that increased the risk of death [2]. A vigilant attitude towards comorbidities not only helps us to gauge the efficacy of surgical approach but also prevent the overall mortality in patients. A proactive attitude to interdepartmental cooperation, with frequent joint assessment of the patient by different faculty members can go a long way in reducing mortalities due to comorbidities.

Regular mortality auditing is a vital step towards educations of health care professionals and strengthening of infrastructural settings. A systemic peer review audit system contributes to changes that decrease adverse effects by changing clinical practices. Multiple approaches to proposed a standardized system of reporting surgical mortality to aid comparison of results from different set ups have been undertaken. Any approach to uniform review must comprise of the following key elements;

-

1.

Whether study is a prospective or a retrospective study: prospective study needs careful mapping of the indices and regular monitoring whereas retrospective study depends on the accuracy and completion of the data.

-

2.

Whether concept of viable and non viable deaths has been applied [17]: failure to identify non viable deaths leads to potentially misleading interpretations.

-

3.

Whether mortality is due to a medical or surgical cause: assumes significance to delineate proper line of treatment for an ailment.

-

4.

Whether effect of operative or non operative has been taken into consideration: to develop appropriate surgical protocols for the patient's condition.

-

5.

Whether mortality index has been viewed in accordance with the total load on the institute and the type of cases the department deals with regularly.

-

6.

Whether the socio-economic aspect of the patient has been taken into consideration.

An audit that satisfactorily accomplishes these objectives can be of significant relevance to a health care provider who seeks to perk up the services provided to a surgical ENT patient.

The value of mortality audits have been recognized universally. Attempts have been made to put in order checklists for reducing mortalities in surgical wards [17]. However, there is an acute paucity of literature regarding mortality data from otorhinolaryngology indoor wards. The state of affairs is even more dismal when data is sought from an Asian perspective. This study has been performed to bridge this gap in flow of knowledge and presented as a template to induce curiosity in the surgical audits in ENT indoor wards. Proper documentation in the mortality register with careful revision of every associated clinical detail must be done. Initiative to build user friendly computer software designed specifically for maintaining mortality records and sensitizing the staff towards the need of regular mortality audit is a stride in the right direction.

Conclusion

Recognition and documentation of the pattern and cause of death in otorhinolaryngology indoor wards is a vital set of health statistic which is mandatory for development of potential interventional health policy. Development of standardized and systemic mortality review protocols for different departments is an essential part of health planning. Evaluations of mortality indices provide information about the quality of health care and the case load at an institution. Health education, health care campaigns, awareness about hygiene, enhancement and accessibility of health care facilities in rural settings, upliftment of socio-economic status and administrative willingness can go a long way in improving the mortality rate in the society.

Limitations

The study, being a retrospective study, depended upon past clinical records. So the possibility of an error in documentation and unavailability of complete case records exists.

Conflicts of interest

We declare that no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Thompson A.M., Ashraf Z., Burton H., Stonebridge P.A. Mapping changes in surgical mortality over 9 years by peer review audit. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1449–1452. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semmens J.B., Aitken J.A., Sanfilippo F.M., Mukhtar S.A., Haynes N.S., Montain J.A. The Western Australian audit of surgical mortality: advancing surgical accountability. Med J Aust. 2005;21:504–508. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb07150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukhalar S.A., Hoffman N.F., MacQuillan G., Semmens J.B. The hospital mortality project: a tool for using administrative data for continuous clinical quality assurance. Health Inf Manag J. 2008;37:9–18. doi: 10.1177/183335830803700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babatunde A., Ayoade L.O., Thanni O.S.O. Mortality pattern in surgical wards of a university teaching hospital in southwest Nigeria: a review. World J Surg. 2013;37:504–509. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1877-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu W.C., Schachat A.P. Transfer from ophthalmology to another service is a marker of high risk medical events. Ophthalmic Surg. 1991;22:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnamurthy V.R., Ishwaraprasad G.D., Rajanna B., Samudyatha U.C., Pruthvik B.G. Mortality pattern and trends in surgery wards: a five year retrospective study at a teaching hospital in Hassan district, Karnataka, India. Int Surg J. 2016;3:1125–1129. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Somnath S., Sudipta C., Prabir K.M., Sudip D., Saibal M., Rashid M.A. Emergency otorhinolaryngological cases in Medical College Kolkata-A statistical analysis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;57:219–225. doi: 10.1007/BF03008018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitcher E.D., Jangu A., Baidoo K. Emergency ear, nose and throat admissions at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital. Ghana Med J. 2007;41:9–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timsit C.A., Bouchene K., Olfatpour B., Herman P., Tran Ba Huy P. Epidemiology and clinical findings in 20,563 patients attending the Lariboisiere Hospital ENT adult Emergency Clinic. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2001;118:215–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chukuezi Anelechi B., Nwosu Jones N. Mortality pattern in the surgical wards: a five year review at Federal Medical Centre, Owerri, Nigeria. Int J Surg. 2010;8:381–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ihegihu C.C., Chianakwana G.U., Ugezu T., Anyanwu S.N.C. A review of in-hospital surgical mortality at the Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi, Nigeria. Trop J Med Res. 2007;11:26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayat Wasim, Fahim Fraz, Arshad Cheema M. Mortality analysis of a surgical unit. Biomed New J. 2004;20:96–98. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Godale L., Mulaje S. Mortality trend and pattern in tertiary care hospital of Solapur in Maharashtra. Indian J Community Med. 2013;38:49–52. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.106628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar V., Ghosh S.K., Sengupta A. Conundrum of sharp metallic foreign body in the airway: case series and review of literature. Bihar Jharkhand J Otolaryngol. 2016;36:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwal A.K., Sethi A., Sethi D., Chopra S. Role of socioeconomic factors in deep neck abscess: a prospective study of 120 patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45:553–555. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acuin J.M. Chronic suppurative otitis media: a disease waiting for solutions. Comm Ear Hear H. 2007;4:17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seymour D.G., Pringe R. A new method of auditing surgical mortality rates: application to a group of elderly general surgical patients. BMJ. 1982;284:1539–1542. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6328.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]