Abstract

Background

There is an increasing need to find natural bioactive compounds for pharmaceutical applications, because they have less harmful side effects compared to their chemical alternatives. Microalgae (MA) have been identified as a promising source for these bioactive compounds, and this work aimed to evaluate the anti-proliferative effects of semi-purified protein extracted from MA against several tumor cell lines.

Methods

Tested samples comprised MA cell extracts treated with cellulase and lysozyme, prior to extraction. The effect of dialysis, required to remove unnecessary small molecules, was also tested. The anti-cancer efficacies of the dialyzed and undialyzed extracts were determined by measuring cell viability after treating four human cancer cell lines, specifically A549 (human lung carcinoma), MCF-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma), MDA MB-435 (human melanoma), and LNCap (human prostate cancer cells derived from a metastatic site in the lymph node). This was compared to the effects of the agents on the human BPH-1 cell line (benign human prostate epithelial cells). The t-test was used to statistically analyze the results and determine the significance.

Results

Against LNCap and A549 cells, the performance of cellulase-treated extracts was better (with p-values < 0.05, as compared to the control) than that of lysozyme-treated preparations (with p-values mainly > 0.05, as compared to the control); however, they had similar effects against the other two tumor cell lines (with p-values mainly < 0.05, as compared to the control). Moreover, based on their effect on BPH-1 cells, extracts from lysozyme-treated MA cells were determined to be safer against the benign prostate hyperplasia cells, BPH-1 (with p-values mainly > 0.05, as compared to the control). After dialysis, the performance of MA extracts from lysozyme-treated cells was enhanced significantly (with p-values dropping to < 0.05, as compared to the control).

Conclusions

The results of this work provide important information and could provide the foundation for further research to incorporate MA constituents into pharmaceutical anti-cancer therapeutic formulations.

Keywords: Proliferation, Anti-cancer agents, Microalgae, Proteins, Enzymatic extraction

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

Microalgae are promising sources of proteins that may have anti-tumor activity. Enzymes have been used to disrupt the rigid cell wall of microalgae for enhanced extraction of proteins, without denaturation. It was important to evaluate the effect of the enzymatic treatment on the anti-cancer bioactivity of the proteins extracts.

What this study adds to the field

The study shows that proteins extracted from enzymatic treated microalgae cells have a good anti-tumor activity. The activity of the semi-purified proteins extracts was shown to increase significantly by dialysis. The results could provide the foundation for further research to incorporate microalgae constituents into pharmaceutical anticancer therapeutic formulations.

Chemotherapy is the most effective method currently available for the treatment of cancer. However, drug resistance is common and associated several harmful side effects, which presents major obstacles for the effective treatment of cancer. Microalgae (MA) have been identified as a promising source of molecules for various pharmaceutical applications [1]. These cells mainly consist of proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and pigments. Extracts from MA have been shown to inhibit the growth of cancer cells in vitro and in vivo, without affecting non-transformed cells [2]. Interest has mainly focused on phenolic compounds of MA, extracted using ethanol [3]. However, it is believed that MA proteins might also have significant bioactivities, especially those having properties not found in other natural sources [4], [5].

For effective extraction from MA cells, the rigid cell wall must be disrupted, allowing the solvent (used for extraction) to reach and dissolve the proteins [6]. The disruption method must be effective in breaking up cell walls, but at the same time, it must protect the fragile proteins from denaturation. The effectiveness of using two enzymes, namely lysozyme and cellulase, for MA cell wall disruption and enhanced protein extraction was discussed in our previous paper [7]. Although we previously reported that lysozyme pretreatment was more effective in enhancing the extraction of proteins from MA, it is important to evaluate the effect of the treatment method on the anti-cancer bioactivity of the extracts, using various cancer and benign cell lines. For this, several cell lines were employed as models of the most common malignancies worldwide. A549 (a human epithelial lung carcinoma cell line), MCF-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma), MDA MB-435 (an M14 melanoma cell line) were used. In addition, LNCap and BPH-1 cells (prostate cancer epithelial cells and a benign prostate cell line, respectively) were also chosen for comparison. As mentioned earlier, the increasing demands for new therapeutic pharmaceutical drugs with low side effects have diverted the attention more then ever towards natural resources. Particularly, due to the diverse structural forms and biological activities of marine microalgae, their chemicals can be used as a valuable source of molecules for new drug development, including novel anticancer compounds [8]. The aim of this work was to identify the MA that potentially contains effective biochemical and chemical anti-cancer agents. Although using miscoalgae appears to be very promising, the rigid walls of microalgae cells need to be disrupted for efficient extraction of their bioactive compounds. Therefore, this work looks into assessing the effect of enzymatic disruption of cells walls, which was shown to be more advantageous than other conventional pre-treatment techniques, on the anti-tumor activity of the extracts.

Materials and methods

Enzymes, chemicals, and strains

Enzymes and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Inc., USA. All MA strains used in this work were fresh water. Chlorella sp. was obtained from a local marine research center in Umm Al-Quwain, UAE. Scenedesmus sp. was kindly provided by Algal Oil Limited, Philippines. A mixed culture of MA was obtained from Ras Al-Khaimah Malaria Centre, UAE. This culture was isolated by serial dilutions followed by streaking on an agar medium, which was incubated until colonies appeared. An individual dominant colony was isolated and inoculated into sterilized Bold Basal medium (BBM), and this species was referred to as M.C. sp. in this work. The composition of the medium and the growth procedure are described in our previous paper [7].

Sample extraction and dialysis

The methods of MA extraction were detailed in our previous paper [7]. Briefly, samples were extracted from 1 g wet harvested MA cells, which was mixed with 3.25 mL of 1 mg/mL lytic enzyme solution (lysozyme or cellulase) and 7.5 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution (PBS) of pH 7.00 and pH 5.00 for lysozyme and cellulase pre-treatments, respectively. These conditions are the respective optimum conditions for each enzyme. Distilled water (9.25 mL) was added to bring the volume to 20 mL and the mixture was incubated in a water bath shaker (SCT-106.026, USA) at 37 °C and 100 rpm for 8 h. The cells were separated by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 30 s and the supernatant was collected as the semi-purified protein sample. Total protein yields were determined as described in our previous publication [7]. A list of samples and their abbreviations used in this work are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Names of microalgae extracts from different strains treated with cellulase and lysozyme.

| Microalgae species | Extracts obtained by cellulase treatments | Extracts obtained by lysozyme treatments |

|---|---|---|

| Chlorella sp. | C-Ch | L-Ch |

| M.C. sp. | C-Mc | L-Mc |

| Scenedesmus sp. | C-Sc | L-Sc |

The MA extract samples were dialyzed for 24 h against pure water in dialysis membrane tubes (100 Da cut-off), (100-500 Dalton molecular weight cut-off, MWCO), Spectrum™, fisherscientific, UK) to remove salts and small molecules. The samples were then freeze-dried and dissolved in distilled water to obtain a constant concentration of 5 mg/mL; these were then used in subsequent tests. The total amount of soluble proteins in the dialyzed samples was determined as previously described [7].

Cell culture preparation

The anti-cancer activities of the extracted MA contents were evaluated against five human cell lines. A549 (human lung carcinoma), MCF-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma), and MDA MB-435 (human breast melanoma) cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM). LNCap (human prostate cells derived from metastatic lymph node site) and BPH-1 (benign human prostate epithelial cells) were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI 1460) medium. Both media were mixed with l-glutamine (20 mM) and phenol red, and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and gentamycin (500 units/mL; Life Technologies). The cells were grown as monolayers in sterile, vented-capped, angle-necked cell culture flasks (Corning), and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator (IR Autoflow Water-Jacketed Incubator; Jencons Nuaire) until confluent.

Cell proliferation assay

Cancer cells were seeded in triplicate into wells of c-sterilized 96-well plates (Orange Scientific, Triple Red Laboratory Technologies) at a density of 5–8 × 104 cells per well. The plates were incubated for 48 h (at which point the cells reached confluence). Cells were washed with PBS buffer, before being treated with MA extracts. Samples of 100 μL volume were added to their designated wells. The MA extracts were tested with tumor cells at concentrations of 5 and 10 mg/mL, as mentioned for each experiment. Two chemotherapy drugs, namely bleomycin (Bleo, 50 μM) and camptothecin (CPT, 10 μM), were used in parallel as references. The cells were then incubated for an additional 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The culture media were then removed and 100 μL of fresh medium with phenol red and FBS, and containing 0.5 mg/mL MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide), was added to the wells and cells were incubated for 1 h. The culture medium was then carefully removed and the insoluble end product (formazan derivatives) was solubilized in 100 μL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The viability of cells was determined based on the optical density (OD) at 550 nm using a 96-well plate reader (MR 700 Dynatech, Dynex). Cell survival was calculated for each sample and expressed as a percentage of control (without the addition of MA extracts or drugs).

Cell morphology

Cells were prepared as mentioned in section Cell proliferation assay. Images of cell morphology were acquired by observing live cell samples under an inverted microscope, using a 10× objective lens, recording phase contrast images with a Samsung camera at a resolution of 1280 × 720 pixels. For presentation, images were processed using Image J software, which is a public domain image processing program developed at the National Institutes of Health. The software was freely downloaded through the link (imagej.nih.gov/ij/download/), with a reference to [9].

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed in triplicate and the average values of the results were determined. The accuracy of the experimental results was evaluated from the standard deviations, shown as error bars in the figures. The standard deviations were calculated from several experimental data with intra- and inter-day precision, using a minimum of three replicates for different concentrations. To determine the significance of an extract as compared to the control, the significance level, or p-value, was calculated using two independent samples t-test. The t-test is used to assess whether the means of two groups are statistically different from each other. In this work, the t-test was used to determine the significance of adding different MA extracts on cells viability, as compared to a control, in which no MA extract was added.

Results and discussion

Effect of MA extracts on tumor cell proliferation

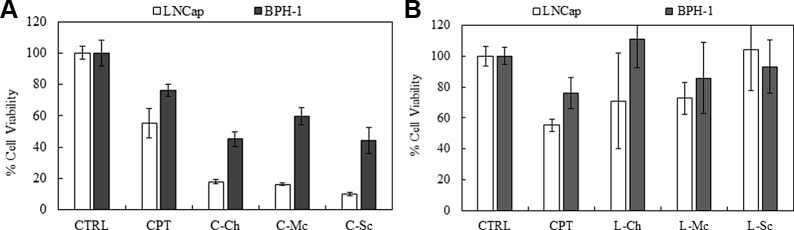

Cell proliferation assays were performed using prostate cancer epithelial cells (LNCap) and a benign prostate cell line (BPH-1) after treatment with the semi-purified samples (10 mg dry material per mL); this was compared to that using a bioactive dose of the chemotherapy drug CPT (10 μM), and the results are shown in Fig. 1A and B for cellulase and lysozyme treatments, respectively. As seen in Fig. 1A, cellulase was able to liberate the chemical constituents from MA that were effective against the LNCap cell line. The viability of LNCap cells after treatment with C-Ch, C-Mc, and C-Sc (see Table 1) was 18, 16, and 10%, respectively, which was lower than that with CPT (55%). Although a higher viability was observed for the benign cell line BPH-1 with all three MA extracts, these values were still in the low range of 40–56%, and much lower than that of CPT (76%). Statistical analysis of the results, shown in Table 2, indicates that the effects of all cellulose treated MA extracts were significant, with p-values less than 0.05.

Fig. 1.

Cell proliferation assay for LNCap and BPH-1 cell lines treated with undialyzed microalgae (MA) extracts at a concentration of 10 mg/mL (A: cellulase-treated and B: lysozyme-treated).

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of the results showing the standard deviation, t-value and p-value.

| Extract | Avg. cell viability, % | Standard deviation | t-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPH1 | ||||

| CPT | 76.06 | 3.94 | 4.562 | 0.0103 |

| C-Ch | 44.99 | 4.91 | 9.978 | 0.0006 |

| C-Mc | 59.65 | 5.31 | 8.935 | 0.0009 |

| C-Sc | 44.32 | 8.20 | 8.321 | 0.0011 |

| L-Ch | 110.73 | 18.49 | −0.964 | 0.3898 |

| L-Mc | 85.80 | 22.96 | 1.042 | 0.3563 |

| L-Sc | 93.14 | 17.20 | 0.658 | 0.5464 |

| L(D)-Ch | 8.03 | 3.12 | 25.309 | <0.0001 |

| L(D)-Mc | 88.72 | 9.24 | 1.819 | 0.1431 |

| L(D)-Sc | 87.27 | 14.33 | 1.437 | 0.2240 |

| LNCap | ||||

| CPT | 55.19 | 9.53 | 7.461 | 0.0017 |

| C-Ch | 17.78 | 1.42 | 32.33 | <0.0001 |

| C-Mc | 16.26 | 1.03 | 33.77 | <0.0001 |

| C-Sc | 9.85 | 1.27 | 35.82 | <0.0001 |

| L-Ch | 70.97 | 30.95 | 1.592 | 0.1866 |

| L-Mc | 72.63 | 10.28 | 3.932 | 0.0171 |

| L-Sc | 104.22 | 26.50 | −0.268 | 0.8017 |

| L(D)-Ch | 5.78 | 2.53 | 24.038 | <0.0001 |

| L(D)-Mc | 72.48 | 1.69 | 7.308 | 0.0019 |

| L(D)-Sc | 28.74 | 8.08 | 12.046 | 0.0003 |

| A549 | ||||

| CPT | 81.91 | 10.00 | 3.008 | 0.0396 |

| C-Ch | 74.98 | 8.08 | 5.044 | 0.0073 |

| C-Mc | 80.65 | 6.48 | 4.715 | 0.0092 |

| C-Sc | 79.78 | 7.99 | 4.117 | 0.0146 |

| L-Ch | 90.69 | 4.92 | 2.562 | 0.0625 |

| L-Mc | 94.11 | 3.40 | 1.972 | 0.1199 |

| L-Sc | 97.72 | 2.35 | 0.867 | 0.4347 |

| L(D)-Ch | 3.71 | 0.33 | 42.62 | <0.0001 |

| L(D)-Mc | 61.34 | 14.99 | 4.313 | 0.0125 |

| L(D)-Sc | 44.67 | 3.52 | 18.242 | 0.0001 |

| MCF-7 | ||||

| CPT | 44.05 | 3.83 | 7.680 | 0.0015 |

| C-Ch | 61.66 | 8.70 | 4.475 | 0.0110 |

| C-Mc | 69.19 | 8.68 | 3.599 | 0.0228 |

| C-Sc | 63.97 | 6.11 | 4.628 | 0.0098 |

| L-Ch | 65.21 | 8.22 | 5.228 | 0.0064 |

| L-Mc | 78.77 | 4.61 | 3.953 | 0.0168 |

| L-Sc | 93.85 | 3.54 | 1.208 | 0.2937 |

| MDA MB-435 | ||||

| CPT | 66.23 | 4.16 | 8.961 | 0.0009 |

| C-Ch | 63.52 | 4.45 | 9.408 | 0.0007 |

| C-Mc | 77.27 | 9.42 | 3.687 | 0.0211 |

| C-Sc | 73.73 | 8.20 | 4.73 | 0.0091 |

| L-Ch | 55.55 | 0.34 | 192.655 | <0.0001 |

| L-Mc | 70.97 | 0.56 | 84.071 | <0.0001 |

| L-Sc | 74.96 | 0.14 | 171.840 | <0.0001 |

In contrast, as shown in Fig. 1B, treatment with the lysozyme-treated MA extracts L-Ch, L-Mc, and L-Sc resulted in higher viability of LNCap cells (71, 73, and 100%, respectively). In addition, the extracts from lysozyme-treated samples were less toxic towards the benign BPH-1 cell line than the cellulase-treated samples. The difference between the MA extracts from cellulase- and lysozyme-treated cells, in terms of performance, was due to the distinct cell disruption mechanism of each enzyme. Cellulase degrades the cellulosic parts of the cell wall, whereas lysozyme degrades polymers containing N-acetyl glucosamine [10]. Thus, lysozyme might have degraded effective agents in the extracts, resulting in lower performance. These results agree with the Statistical analysis of the results, shown in Table 2. The significance values indicate that the effects of all lysozyme treated MA extracts were insignificant, with p-values larger than 0.05. Except for L-Mc, which showed slight significance towards LNCap with a p-value of 0.0171.

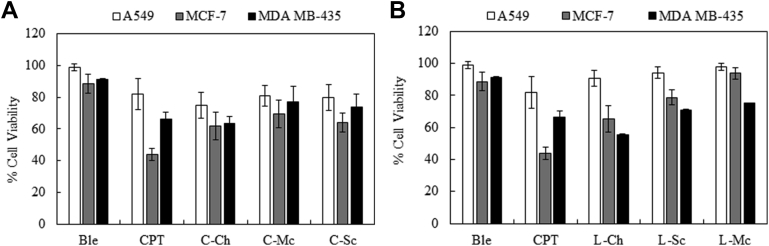

Cellulase- and lysozyme-treated MA extracts were also tested against three other tumor cell lines (A549, MCF-7, and MDA MB-435) and compared to two reference drugs (Bleo, 50 μM and CPT, 10 μM), shown in Fig. 2, respectively. The efficacy of cellulase-treated MA samples against the A549 tumor cell line was lower than that against LNCap with larger p-values (p-values for A549 were in the range of 0014-0.009 and for LNCap were all <0.0001), but still higher than that of the lysozyme-treated MA samples (with p-values >0.05 for all). The viabilities of A549 cell lines treated with C-Ch, C-Sc, and C-Mc were 75, 81, and 20%, respectively, whereas the viabilities of those treated with L-Ch, L-Sc, and L-Mc were 91, 95, and 98%, respectively. Against MCF-7 cells, the growth inhibitory effects of cellulase- and lysozyme-treated MA samples were similar (with similar p-values), with the exception of L-Sc (with p-value >0.05). The viabilities of MCF-7 cells treated with the three cellulase-treated samples were 62, 70, and 64%, respectively, and those of the lysozyme-treated samples were 65, 79, and 93%, respectively. The efficacy of the chemical drug CPT against A549 cells was relatively low, with an associated viability of 82%; however, this agent performed better against MCF-7 cells, with an associated viability of only 44%. The low activity of CPT, which is a natural isolate from the bark and stem of the Camptotheca acuminate tree, was due to its low solubility and uptake. Therefore, CPT must dissolved in DMSO to improve cell permeability and enhance its effectiveness. However, a very low concentration of DMSO was used to avoid any possible adverse effects on benign cells. In addition, it was necessary to use a low dose of CPT (10 μM) because this drug is associated with clinical adverse drug reactions and it was previously reported to inhibit the growth of PC12 cells (a cell line derived from a pheochromocytoma) [11].

Fig. 2.

Cell proliferation assay for A549, MCF-7, and MDA MB-435 cell lines treated with undialyzed microalgae (MA) extracts at a concentration of 10 mg/mL (A: cellulase-treated and B: lysozyme-treated).

Bleo, which is a natural extract from the bacterium Streptomyces verticillus, was ineffective against both tumor cells lines, with associated viability values of 91 and 89%, respectively. The major limitation of Bleo therapy is its high toxicity towards normal cells [12]. Initially, doses higher than 50 μM were used, and these resulted in high toxicity against the benign cell line (BPH-1). Therefore, the dose was reduced to a reasonable level of 50 μM. Several reported articles have investigated the use of bleomycin in combination with other techniques such as photochemical internalization and electrochemical internalization to overcome its resistance and minimize its toxic effects [13].

In contrast, lysozyme-treated MA samples performed slightly better than cellulase-treated MA samples against MDA MB-435 tumor cells. The viabilities of cells treated with L-Ch, L-Sc, and L-Mc were 56, 71, and 75%, respectively, compared to those of cells treated with C-Ch, C-Sc, and C-Mc, which were 75, 81, and 80%, respectively. The efficacy of CPT was not high, with an associated viability of 77%. The efficacy of Bleo was also low, with an associated viability of 91%.

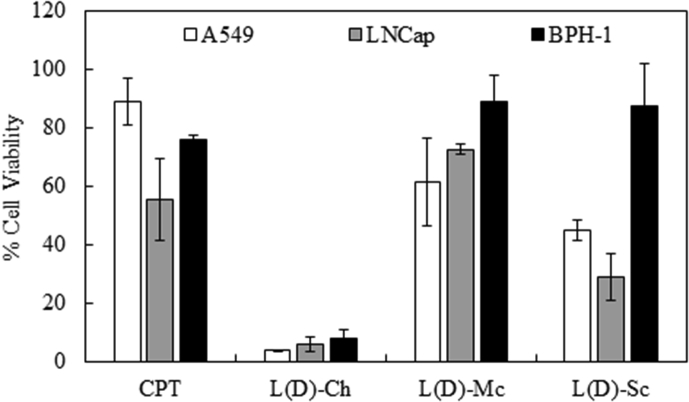

Effect of lysozyme-treated dialyzed MA extracts on tumor proliferation

Despite its lower toxicity, lysozyme-treated MA extracts were safer with respect to activity against the benign BPH-1 cells. Therefore, we next assessed whether it was possible to enhance the efficacy of the bioactive chemical constituents including the proteins. Dialysis was therefore conducted to remove all mineral salts and small compounds (100-500 Dalton Molecular Weight Cut-Off, MWCO) that could affect the activity of the extracts. The effect of the bioactive constituents from lysozyme-treated MA extracts after dialysis was evaluated using two tumor cell lines (A549 and LNCap), and compared to that using the benign cell line (BPH-1). The results in Fig. 3 clearly show that the dialyzed samples performed much better, despite the use of a lower concentration of dry materials (5 mg/mL) compared to that with the undialyzed sample (10 mg/mL). Dialyzed L(D)-Ch showed the highest efficacy against the two tumor cell lines, with A549 and LNCap cell viabilities of only 4 and 6%, respectively. However, its effect on the benign cell line was also severe, with an associated viability of only 8%, thus rendering this extract an undesirable choice. L(D)-Mc was the least effective, with associated viabilities of 62, 73, and 89% when used with A549, LNCap, and BPH-1 cell lines, respectively. The most promising finding was with L(D)-Sc, which showed good toxicity towards the tumor cell lines A549 and LNCap, with associated viabilities of 45 and 29%, respectively. When used with the benign cell line (BPH-1), this preparation also resulted in a much higher viability (88%). The enhanced significance of the dialyzed samples is reflected in the much smaller p-values shown in Table 2.

Fig. 3.

Cell proliferation assay for A549, LNCap, and BPH-1 cell lines treated with dialyzed (D) sample at a concentration of 5 mg/mL for lysozyme-treated microalgae (MA) extracts.

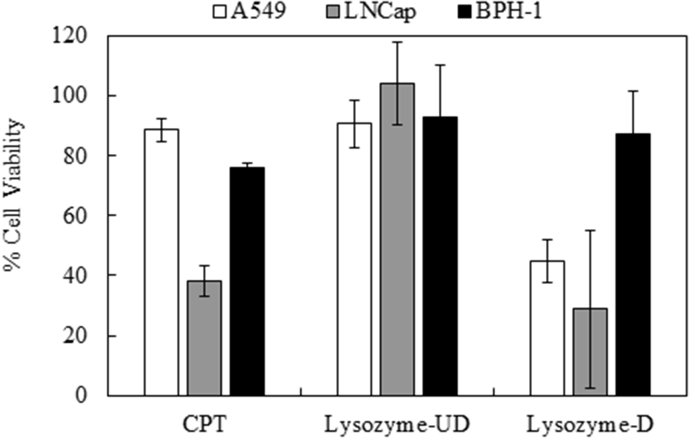

Fig. 4 shows the comparison between the dialyzed and un-dialyzed L-Sc samples, with respect to the inhibition of proliferation of A549 and LNCap cell lines; this was compared to the effect of the active dose of CPT. The results clearly show enhanced effects for the L(D)-Sc extract with dialysis. Although, the concentrations of the dialyzed samples were half that of the original un-dialyzed preparations, treatment resulted in lower viabilities for A549 cells (55%) and LNCap cells (30%). The observed reduced viability suggested the importance of dialysis, which concentrated the highly bioactive chemical constituents within the extracts. As mentioned earlier, the stronger performance of the dialyzed samples was due to the concentration of bioactive constituents and the removal of smaller components, which might have hindered the bioactivity of the major chemical constituents.

Fig. 4.

Cell proliferation assay for A549 and LNCap cell lines treated with undialyzed (UD) samples at a concentration of 10 mg/mL and dialyzed (D) samples at a concentration of 5 mg/mL dry material, from lysozyme-treated Scenedesmus sp. cells.

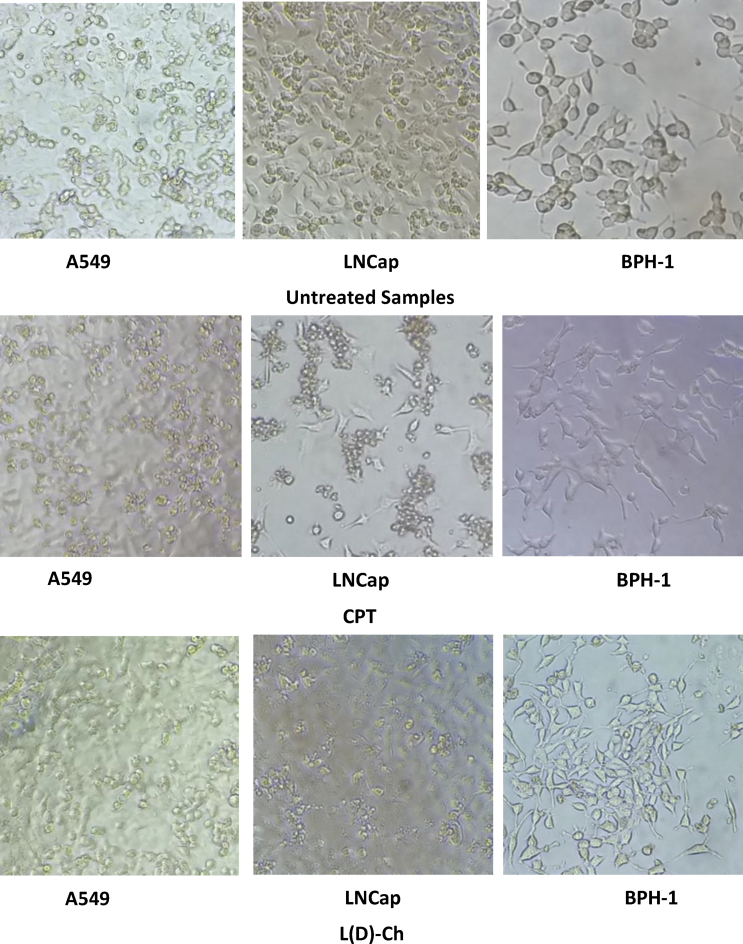

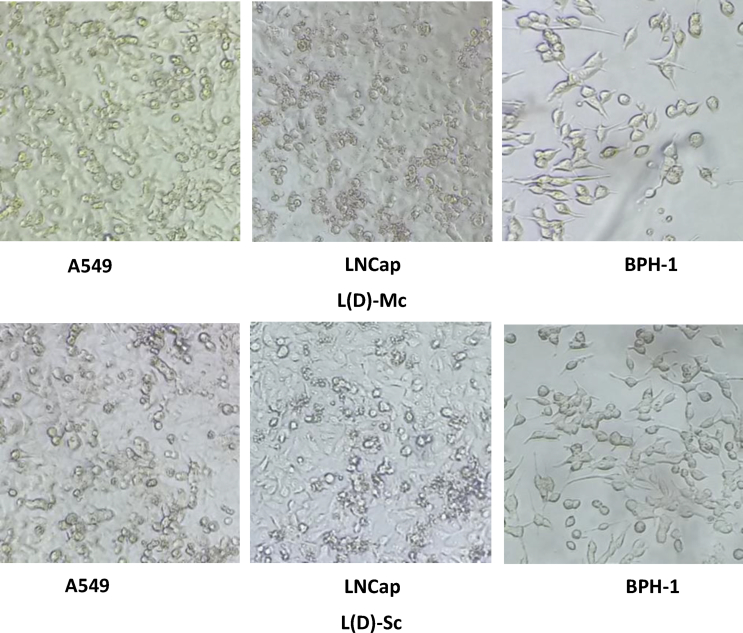

Cell morphology of cancer cell lines treated with dialyzed lysozyme MA samples

Cell morphologies of A549 and LNCap tumor cell lines and the BPH-1 benign cell line were observed using a phase contrast microscope, and the results are shown in Fig. 5. In a healthy growing cell culture, the three untreated cell lines were adherent and epithelial-like, as shown in Fig. 5. The chemotherapy drug, used as a reference, is a well-known inducer of apoptosis, and this agent caused cell cluster formation and detachment from the surface, when administered to A549 and LNCap cells. The effect of CPT on A549 cells was less severe than that on LNCap cells, which is in agreement with the results shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2.

Fig. 5.

Cell morphology of selected cell lines after a 24-hours incubation with microalgae (MA) lysozyme-treated samples. Phase contrast images of A549, LNCap, and BPH-1 cell lines were obtained using a 10× objective. Scale bar represents 5 mm.

Dialyzed L(D)-Ch affected the morphology of both cancer and benign cells in a similar manner to that observed with CPT-treated samples, in agreement with the results shown in Fig. 3. Treatment with the dialyzed extract significantly affected the morphology, causing cells to become round and loosely clustered, similar to suspension cells, with reduced adherence to the surface. This indicates that the affected cells might have undergone apoptosis, due to the effect of the MA samples. Further investigation is required to test this hypothesis. Comparing the effects of CPT to those of L(D)-Ch suggested higher toxicity with the latter, which agrees with the MTT results. Treatment with L(D)-Mc did not result in significant changes to cell morphology for all three cell lines. In addition, this effect was greater for tumor cells than for benign cells. These results also agree well with those shown in Fig. 3.

Conclusion

MA constituents comprise a unique pool of novel metabolites that have a wide and valuable therapeutic effect for many diseases. Cell lines, four tumor and one benign, were treated with semi-purified MA extracts, after which the viability was determined and compared to that after treatment with chemical drugs. Lower viability (higher toxicity) was observed with extracts from cellulase-treated MA cells, when compared to that with the chemical drug and extracts from lysozyme-treated cells. However, the extract from cellulase-treated samples resulted in lower viability of benign cells. Through dialysis, the extracts from lysozyme-treated MA cells showed much better performance. It was shown that the activity of the contents of MA samples was specific to cancer cells, and thus might show better efficacy for certain cancer types. Dialyzed extracts from Scenedesmus sp. cells treated with lysozyme were found to represent a promising anti-tumor agent, and had activity against A549 and LNCap cells. The results of this work provide important information that might lead to further research and the eventual incorporation of MA constituents into pharmaceutical therapeutic anti-cancer formulations.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Zayed Centre for Health Sciences (Fund# 31R019).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by Chempharm Research Ltd, UK. Gratitude is also extended to Prof. Koroush Salihi from the New York University, Abu Dhabi, for providing samples of Chlamydomonas sp. used in this work.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

Contributor Information

Sinan Battah, Email: shbatt@essex.ac.uk.

Sulaiman Al-Zuhair, Email: s.alzuhair@uaeu.ac.ae.

References

- 1.Amaro H.M., Barros R., Guedes A.C., Sousa-Pinto I., Malcata F.X. Microalgal compounds modulate carcinogenesis in the gastrointestinal tract. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talero E., García-Mauriño S., Ávila-Román J., Rodríguez-Luna A., Alcaide A., Motilva V. Bioactive compounds isolated from microalgae in chronic inflammation and cancer. Mar Drugs. 2015;13:6152–6209. doi: 10.3390/md13106152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nigjeh S.E., Yusoff F.M., Alitheen N.B.M., Rasoli M., Keong Y.S., Omar A.R. Cytotoxic effect of ethanol extract of microalga, Chaetoceroscalcitrans, and its mechanisms in inducing apoptosis in human breast cancer cell line. Biomed Res Int. 2013;783690 doi: 10.1155/2013/783690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afify A.M., El-Beltag H.S., Fayed S.A., Shalaby E.A. Acaricidal activity of different extracts from Syzygiumcumini L. Skeels (Pomposia) against Tetranychusurticae Koch. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2011;13:59–64. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60080-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markou G., Nerantzis E. Microalgae for high-value compounds and biofuels production: a review with focus on cultivation under stress conditions. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31:1532–1542. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taher H., Al-Zuhair S., AlMarzoqui A., Haik Y., Farid M. Effective extraction of microalgae lipids from wet biomass for biodiesel production. Biomass Bioenerg. 2014;66:159–167. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Zuhair S., Ashraf S., Hisaindee S., Darmaki N.A., Battah S., Svistunenko D. Enzymatic pre-treatment of microalgae cells for enhanced extraction of proteins. Eng Life Sci. 2017;17:175–185. doi: 10.1002/elsc.201600127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo X., Su P., Zhang W. Advances in microalgae-derived phytosterols for functional food and pharmaceutical applications. Mar Drugs. 2015;13:4231–4254. doi: 10.3390/md13074231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerken H.G., Donohoe B., Knoshaug E.P. Enzymatic cell wall degradation of Chlorella vulgaris and other microalgae for biofuels production. Planta. 2013;237:239–253. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1765-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang C., Chen S., Bao J., Zhang Y., BHuang B., Jia X. Low doses of Camptothecin induced hormetic and neuroprotective effects in PC12 cells. Dose Response. 2015;31:1–7. doi: 10.1177/1559325815592606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sultan A.A., Jerjes W., Berg K., Høgset A., Mosse C.A., Hamoudi R. Disulfonated tetraphenyl chlorin (TPCS2a)-induced photochemical internalisation of bleomycin in patients with solid malignancies: a phase 1, dose-escalation, first-in-man trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1217–1229. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shan L., Yang M., Li X., Liu Y.Y., Cao Y. Amplified detection of bleomycin based on an electrochemically driven recycling strategy. Anal Methods. 2014;6:5573–5577. [Google Scholar]