Abstract

Background

To clarify the effect of induction chemotherapy (ICT) in patients with advanced pharyngeal and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (PLSCC) treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT).

Methods

Patients with treatment-naïve nonmetastatic advanced PLSCC were stratified according to disease stage (III or IV) and resectability before being randomized to either a ICT/CCRT or CCRT arm. A cisplatin/tegafur-uracil/leucovorin regimen was administered during ICT and CCRT. The primary end point was overall survival (OS).

Results

We enrolled 151 patients during December 2006 to February 2011. The median follow-up of surviving patients was 54.5 months. The ICT/CCRT arm included more patients with hypopharynx cancer (57.1% vs 40.5%, p = 0.09) and N2 or N3 diseases (85.7% vs 74.4%, p = 0.02). In the ICT/CCRT and CCRT arms, the 5-year OS was 48.1% and 53.2% (p = 0.45); progression-free survival (PFS) was 31.8% and 55.6% (p = 0.015); and locoregional control (LRC) was 37.7% and 56.2% (p = 0.026), respectively. The adverse events and compliance to radiotherapy were similar. However, the proportion of patients receiving a total dose of cisplatin during CCRT <150 mg/m2 was higher in the ICT/CCRT arm (46.8% vs 16.2%; p = 0.000) and independently predicted poorer PFS and LRC in multivariate analysis.

Conclusion

OS did not vary between the ICT/CCRT and CCRT arms. However, poorer compliance to CCRT and inferior LRC and PFS were observed in the ICT/CCRT arm. Optimizing the therapeutic ratio in both ICT and CCRT settings are necessary for developing a sequential strategy for patients with advanced-stage PLSCC.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, Chemoradiotherapy, Induction chemotherapy

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

The role of induction chemotherapy (ICT) in patients of advanced pharyngeal and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (PLSCC) treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) remains to be clarified.

What this study adds to the field

This study showed that ICT/CCRT and CCRT provides similar overall survival, but poorer compliance to CCRT and inferior locoregional control and progression-free survival were observed in the ICT/CCRT arm. Optimizing the therapeutic ratio in both ICT and CCRT settings are necessary for developing a sequential strategy for advanced PLSCC.

Numerous attempts have been made to improve the outcomes in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) by combing radiotherapy (RT) with chemotherapy (CT) since the data of the Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy on Head and Neck Cancer (MACH-NC) revealed a 6.5% 5-year absolute survival benefit of concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) [1]. CCRT has been proposed to be the ideal approach to incorporate CT into RT for treating advanced HNSCC. Generally, no overall survival (OS) benefit of induction CT (ICT) schedules has been identified. Only a marginal improvement in the OS was observed in ICT trials using a cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (PF) combination [1]. Although phase III ICT trials for HNSCC have demonstrated a stronger overall response and survival rate for a docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil (TPF) combination compared with a PF combination [2], [3], [4], randomized trials of CCRT preceded or not preceded by ICT TPF have not yet supported the use of ICT [5], [6].

Although the role of ICT in managing HNSCC is still being explored and debated, it is used as a common clinical treatment for HNSCC. The potential clinical advantages of ICT in addition to organ-function preservation [7], [8] are to provide early symptom and function improvement before RT, rapidly shrink tumors and, thus, reduce the requirement for urgent interventions (e.g., tracheostomy for airway obstruction, feeding tube for swallowing dysfunction), bridge definitive treatment when immediate RT initiation is not possible, eradicate micrometastasis, and in vivo assess the treatment response to provide prognostic information for subsequent treatment. These potential advantages are commonly required for treating patients with advanced HNSCC, and ICT is reported to render a survival benefit in patients with unresectable HNSCC [9]. However, according to the preceding considerations, patients with advanced tumors or a compromised health status for CCRT may be treated with ICT during daily practice. The 3-year OS of our patients with advanced-stage pharyngeal or laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (PLSCC) treated with CCRT and ICT was 60% and 45%, respectively. Whether the inferior outcome of ICT in daily practice is attributable to treatment selection bias requires clarification.

In Taiwan, 80%–90% of HNSCC patients are betel quid chewers, and >40% of our patients experienced ≥ grade 3 stomatitis following ICT PF [10]. The high incidence of severe stomatitis was due to betel quid-chewing related oral mucosa change [11]. Severe mucositis, poor compliance, and reduced dose intensity worsened the therapeutic outcomes for ICT PF [10]. We have developed cisplatin (P)/tegafur (T) or tegafur-uracil (U)/leucovorin (L) combined regimens since 2002. To ameliorate emesis and nephrotoxicity, cisplatin at 100 mg/m2 triweekly was modified to 50 mg/m2 biweekly, and to ameliorate stomatitis and maintain efficacy, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) at 1000 mg/m2/d through 120-h infusion was replaced with daily oral 5-FU prodrugs (tegafur 800 mg/d or tegafur-uracil at 300 mg/m2/d) [12]. According to a dose-finding study investigating toxicity, oral leucovorin at 60 mg/d was used in combination with tegafur for protracted treatment [13]. PUL and PTL combinations had lesser toxicity, particularly for severe stomatitis (5%–7%), and stronger efficacy compared with PF in our patients [14], [15]. Moreover, oral 5-FU prodrugs can be easily administered as radiosensitizers during CCRT. CCRT with PTL in patients of advanced PLSCC yielded a 5-year OS of 59.7% [16].

This randomized study examining PUL during ICT and CCRT was designed to clarify the effect of ICT on CCRT.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients with measurable nonmetastatic histologically proven stage III or IV PLSCC were eligible if either their tumors were declared unresectable by a multidisciplinary team consensus or they were candidates for organ preservation. The American Joint Committee on Cancer criteria (2002) were used for disease staging [17]. The included patients were aged 18–70 years, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–2, and adequate bone marrow function (leukocyte count ≥ 4000/L; platelets ≥ 100,000/L), renal function (serum creatinine < 2.0 mg/dL), and liver function (total bilirubin ≤1.5 × the upper limit of normal (ULN); serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase and serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase ≤ 2.5 × the ULN). Exclusion criteria were a previous history of malignancy, prior CT or RT, serious concomitant illness (e.g., liver cirrhosis, angina, or myocardial disease), uncontrolled infection and intestinal obstruction, malabsorption, and any condition that restricted oral medication. Patients fed through nasogastric tubes or gastrostomy tubes without intestinal malabsorption or obstruction were eligible.

Study design

This randomized phase II trial compared ICT/CCRT with CCRT. The PUL regimen was administered biweekly during ICT and CCRT. Eligible patients were stratified into 4 groups on the basis of 2 factors: tumor resectability (resectable vs unresectable) and disease stage (III vs IV). A consensus on resectability was provided by a multidisciplinary team. Randomization codes were generated independently for each stratum. A permuted block randomization scheme was used to generate the randomization codes so that the number of patients assigned to the 2 treatment arms was approximately equal. The institutional review board of our institution approved this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before therapy.

The biweekly PUL regimen consisted of cisplatin at 50 mg/m2 on day 1 as well as tegafur-uracil (UFUR, TTY Biopharm Co. Ltd, Taipei, Taiwan) at 300 mg/m2/d and leucovorin at 60 mg/d on days 1–14 [15]. The ICT/CCRT arm patients received ICT PUL every 2 weeks for 6 cycles, unless disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, withdrawal of patient consent, or stationary or progressive disease after 3 PUL cycles occurred. PUL was administered concurrently during CCRT in both arms. For patients with disease progression or unacceptable toxicity caused by ICT PUL, the CT regimens used for post-ICT CCRT were revised at the discretion of the physicians.

External beam RT with a 6-MV X-ray was administered using intensity-modulated radiotherapy techniques. Patients received 2.0 Gy/d daily fractions 5 times per week. The gross target volume (GTV) was determined according to the clinical findings of nasofiberscopy, magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography, and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography scans. The initial prophylactic clinical target volume included neck lymphatics at risk and margins at least 1 cm beyond the GTV, and was delivered a dose of 46–50 Gy. The radiation field was then reduced to the GTV with 0.5-cm margins and the initial grossly involved nodal area, and was delivered 70–76 Gy. The maximal dose was restricted to 50 Gy and 60 Gy for the spinal cord and brain stem, respectively. The mean dose for parotid sparing was restricted to 23 Gy, and the dose delivered to uninvolved constrict muscles was restricted to 56 Gy, when possible.

Surgery for resectable residual disease was performed 6–12 weeks following CCRT. Elective neck dissection was not performed for initial N2 or N3 nodal disease in cases with complete responses following CCRT.

Tumor response was assessed through clinical evaluation and imaging studies. Responses were characterized according to the WHO criteria following the third and sixth ICT cycles, 12 weeks following the end of CCRT, and during follow-up visits for disease progression. Post-CCRT monitoring was performed monthly during the first year, bimonthly during the second year, quarterly during the third year, and biannually thereafter until death or data censoring. Adverse events were assessed according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0.

Statistical analysis

The primary end point of this study was OS. Secondary end points were progression-free survival (PFS), locoregional control (LRC), distant metastasis (DM), and toxicity profiles. According to the 3-year OS of patients with advanced PLSCC treated with CCRT (60%) and those treated with ICT/CCRT (45%) in our daily practice, a sample size of 200 patients was required to achieve 80% power for detecting a 15% difference between the two therapeutic schema by using a 2-sided log-rank test with a type l error rate of 5%.

OS was the time from study randomization to death due to any cause. PFS was the time from study randomization to disease progression, relapse, or death due to any cause. LRC was assessed from the randomization date until failure of disease control above the clavicle. The DM end point was the time from study randomization to the occurrence of the disseminated disease.

All time-to-event end points were analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Adverse events were analyzed in a safety population administered randomly assigned treatments. Fisher's exact test was used to compare binary and categorical variables. Continuous measurements were compared using independent sample t tests. Kaplan–Meier curves were used for determining time-to-event data. Time-to-event intervals were compared between groups by using log-rank tests and a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. The variables in multivariate analysis were sex; performance status; primary tumor location; pathologic differentiation; T, N, and, overall stages; resectability; radiation dose; total dose of cisplatin during CCRT; and the CT arm. All statistical computations were performed using SPSS software, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

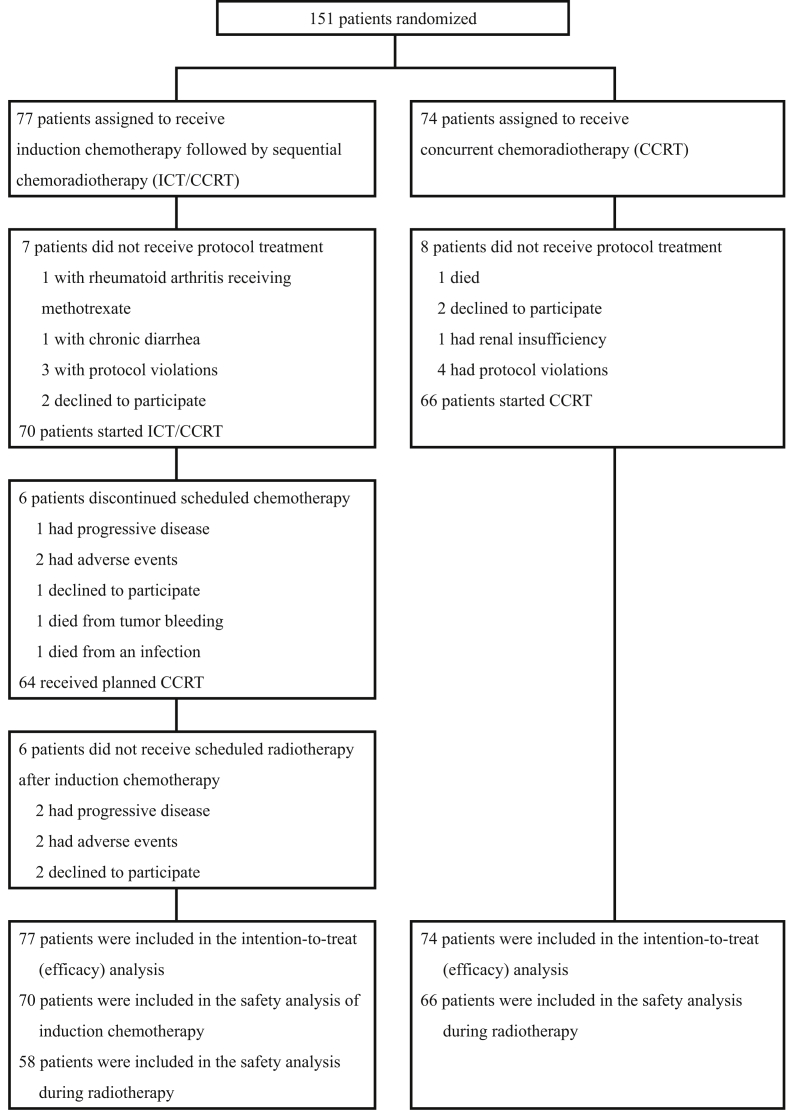

We enrolled 151 patients in the study between December 2006 and February 2011. The study was suspended because of slow accrual and poor end points in the ICT/CCRT arm during interim analysis. Seventy-seven patients were assigned to the ICT/CCRT arm and 74 patients to the CCRT arm (Fig. 1). Most patients were men and relatively young. The ECOG performance status was 0–1 in 95.4% patients. Primary sites included the hypopharynx 49.0%, oropharynx 41.1%, and larynx 9.9%, and of the patients, 55.6% had T4 stage tumors, 10.6% had N3 stage disease, 92.1% had stage IV disease, and 23.8% had unresectable disease.

Fig. 1.

Patient enrollment and outcomes.

Most of the patient characteristics were well balanced between the 2 arms. However, compared with the CCRT arm, more patients in the ICT/CCRT arm had hypopharynx cancer (57.1% vs 40.5%, p = 0.09) and N2 or N3 disease (85.7% vs. 74.4%, p = 0.02) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (intention-to-treat population).

| Characteristic | ICT/CCRT (n = 77) |

CCRT (n = 74) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 70 (90.9) | 70 (94.6) | 0.39 |

| Female | 7 (9.1) | 4 (5.4) | |

| Age | |||

| Mean | 51.2 ± 8.4 | 52.0 ± 8.3 | 0.89 |

| Range | 34–70 | 34–68 | |

| ECOG Performance status | |||

| 0 | 18 (23.4) | 14 (18.9) | 0.73 |

| 1 | 55 (71.4) | 57 (77.0) | |

| 2 | 4 (5.2) | 3 (4.1) | |

| Cancer site | |||

| Oropharynx | 28 (36.4) | 34 (45.9) | 0.09 |

| Hypopharynx | 44 (57.1) | 30 (40.5) | |

| Larynx | 5 (6.5) | 10 (13.5) | |

| Cancer site | |||

| Oropharynx | 28 (36.4) | 34 (45.9) | 0.250 |

| Non-oropharynx | 49 (63.6) | 40 (54.1) | |

| Tumor status | |||

| T1 | 8 (10.4) | 4 (5.4) | 0.41 |

| T2 | 16 (20.8) | 11 (14.9) | |

| T3 | 16 (20.8) | 12 (16.2) | |

| T4A | 27 (35.1) | 34 (45.9) | |

| T4B | 10 (13.0) | 13 (17.6) | |

| Node status | |||

| N0 | 8 (10.3) | 10 (13.5) | 0.02 |

| N1 | 3 (3.9) | 9 (12.2) | |

| N2 | 53 (68.8) | 52 (70.3) | |

| N3 | 13 (16.9) | 3 (4.1) | |

| Stage | |||

| III | 4 (5.2) | 8 (10.8) | 0.37 |

| IVA | 52 (67.5) | 50 (67.6) | |

| IVB | 21 (27.3) | 16 (21.6) | |

| Stage | |||

| III | 4 (5.2) | 8 (10.8) | 0.24 |

| IV | 73 (94.8) | 66 (89.2) | |

| Resectability | |||

| Resectable | 59 (76.6) | 56 (75.7) | 0.83 |

| Unresectable | 18 (23.4) | 18 (24.3) | |

Abbreviations: CCRT: concurrent chemoradiotherapy; ICT/CCRT: induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

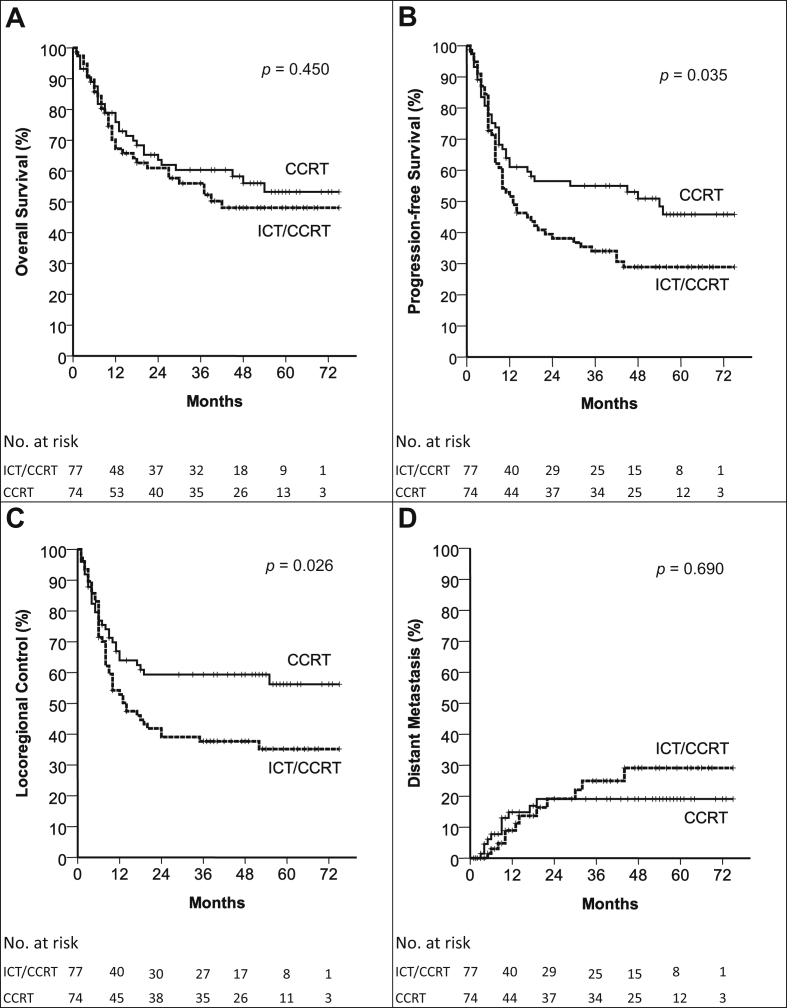

The median follow-up time of surviving patients was 54.5 months (range, 3–75 months). The ICT/CCRT arm had a 5-year OS rate of 47%, compared with 52% in the CCRT arm (p = 0.450). Furthermore, PFS was 29% and 45% (p = 0.035), LRC was 35% and 56% (p = 0.026), and DM was 28% and 18% (p = 0.69) at 5 years in the ICT/CCRT and CCRT arms, respectively (Fig. 2). The second primary malignancy rate was 10% and 16% in the ICT/CCRT and CCRT arms, respectively (p = 0.203). Disease failure occurred in 83 patients (54.9%), namely 51 (66.2%) in the ICT/CCRT arm and 32 (43.3%) in the CCRT arm. The rates of the first failure event being at locoregional, distant, or locoregional and distant sites were 50.6%, 3.9%, and 11.7%, respectively, in the ICT/CCRT arm and 28.4%, 2.7%, and 12.2% in the CCRT arm. Salvage surgery for residual or relapsed disease was performed in 12 (15.6%) ICT/CCRT patients and 6 (8.1%) CCRT patients (p = 0.370).

Fig. 2.

OS (A), PFS (B), LRC (C), and DM (D) in the ICT/CCRT and CCRT Arms in the Intention-to-Treat Analysis. Abbreviations used: CCRT: concurrent chemoradiotherapy; ICT/CCRT: induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy; DM: distant metastasis; LRC: locoregional control; OS: overall survival; PFS: progression-free survival.

Patients who received at least one cycle of PUL were included in the safety analysis (Table 2). The major grade 3–4 adverse event during ICT PUL was diarrhea (14.3%). Adverse events during CCRT in the ICT/CCRT and CCRT arms were neutropenia (12.0% and 12.1%, respectively), anemia (32.8% and 10.6%), stomatitis (70.7% and 59.1%), and dermatitis (12.0% and 15.1%). No difference was observed between the study arms regarding the parameters of compliance during RT. However, the proportion of patients receiving a total dose of cisplatin during CCRT <150 mg/m2 was higher in the ICT/CCRT arm (46.8% vs 16.2%; p = 0.000). The radiotherapeutic dose was <70 Gy in the ICT/CCRT arm because of death due to hyperglycemic hyperosmolar nonketotic coma (1 patient), bleeding (1 patient), infection (3 patients), fatigue (1 patient), and withdrawal of consent (1 patient) and in the CCRT arm because of death due to bleeding (1 patient), infection (5 patients), and withdrawal of consent (2 patients).

Table 2.

Adverse events and therapeutic compliance.

| Grade 3–4 adverse events | ICT/CCRT |

CCRT |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| ICT (n = 70) |

CCRT (n = 58) |

CCRT (n = 66) |

|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Neutropenia | 0 (0) | 7 (12.0) | 8 (12.1) |

| Anemia | 5 (7.1) | 19 (32.8) | 7 (10.6) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 (1.4) | 2 (3.4) | 2 (3.0) |

| Emesis | 1 (1.4) | 4 (6.9) | 0 (0) |

| Mucositis | 0 (0) | 41 (70.7) | 39 (59.1) |

| Dermatitis | 1 (1.4) | 7 (12.0) | 10 (15.1) |

| Diarrhea | 10 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.0) |

| Renal insufficiency | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) |

| Liver dysfunction | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.5) |

| Compliance during CCRT | |||

| Tube feeding | 36 (62) | 43 (65) | |

| RT dose: median (range) (Gy) | 72 (12–76) | 72 (24–76) | |

| RT dose <70 Gy | 7 (12) | 8 (12) | |

| RT duration: median (range) (days) | 52 (7–90) | 53 (19–150) | |

| Total dose of cisplatin in CCRT | |||

| <150 mg/m2 | 36 (46.8) | 12 (16.2) | |

| Hospitalization | 15 (25.8) | 20 (30.3) | |

| Body weight loss: mean (range) | 8.9% (0–30%) | 7.6% (0–20%) | |

Abbreviations: CCRT: concurrent chemoradiotherapy; ICT/CCRT: induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

In multivariate analyses (Table 3), prognostic factors of OS included unresectable disease, stage IV disease, non-oropharyngeal primary tumors, and a radiation dose < 70 Gy; stage IV disease, non-oropharyngeal primary tumors, a radiation dose < 70 Gy, and total dose of cisplatin during CCRT < 150 mg/m2 were associated with poorer PFS and LRC. Patients with an ECOG performance status of 2 or with hypopharyngeal tumors had an increased risk of DM. The treatment arm (ICT/CCRT vs CCRT) was not at a significant risk factor for time-to-event end points.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis (N = 151).

| Characteristics | Overall survival |

Progression-free survival |

Locoregional control |

Distant metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) p-value | HR (95% CI) p-value | HR (95% CI) p-value | HR (95% CI) p-value | |

| Unresectable disease | 2.008 (1.156–3.487) | NS | NS | NS |

| 0.013 | ||||

| Stage IV disease | 7.229 (0.993–52.638) | 4.387 (1.376–13.950) | 4.078 (1.266–13.134) | NS |

| 0.051 | 0.012 | 0.018 | ||

| Non-oropharyngeal cancer | 3.574 (2.018–6.332) | 2.802 (1.742–2.509) | 2.516 (1.552–4.159) | NS |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Hypopharyngeal cancer | NS | NS | NS | 3.099 (1.264–7.600) |

| 0.013 | ||||

| RT dosage <70 Gy | 8.001 (4.278–14.63) | 4.952 (2.802–8.751) | 6.392 (3.547–11.521) | NS |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Accumulated dose of cisplatin during radiotherapy <150 mg/m [2] | NS | 1.922 (1.200–3.079) | 2.641 (1.613–4.325) | NS |

| 0.002 | 0.000 | |||

| ECOG Performance status = 2 | NS | NS | NS | 4.946 (1.448–16.891) |

| 0.011 | ||||

| Treatment arm | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NS, not significant.

Tracheostomy and tube feeding-free disease-free survival were determined to examine organ function preservation. The 5-year disease-free survival was 33% and 44% in the ICT/CCRT and CCRT arms, respectively (p = 0.103). The tracheostomy and tube feeding-free rate in patients with disease-free survival was 89% and 96% in the ICT/CCRT and CCRT arms, respectively (p = 0.367).

Discussion

This trial was suspended prematurely in 2011 because of slow accrual and poor end points in the ICT/CCRT arm during interim analysis. With insufficient statistical power, the OS in the ICT/CCRT arm was not poorer than that in the CCRT arm in patients with advanced PLSCC. However, patients treated with ICT/CCRT had poorer PFS and LRC.

The higher prevalence of hypopharynx cancer (57.1% vs 40.5%, p = 0.09) and N2 or N3 disease (85.7% vs 74.4%, p = 0.02) in the ICT/CCRT arm may account for the poorer PFS and LRC. The 5-year OS of our patients and those in the Taiwan Cancer Registry treated between 2004 and 2010 was 100% and 43% for those with stage III oropharyngeal cancer, 65% and 31% for those with stage IV oropharyngeal cancer, 75% and 37% for those with stage III hypopharyngeal cancer, and 33% and 23% for those with stage IV hypopharyngeal cancer, respectively [18]. These findings evidence that stage IV disease and non-oropharyngeal cancer are prognostic factors for a poorer outcome. A randomized study with stratification of the cancer site may be needed for refining the outcome assessments.

Although the incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV)-related site HNSCC (1.3 per 100,000 in 1995 to 3.3 per 100,000 in 2009, annual percentage change (APC) 56.9, p < 0.0001) increased more rapidly than did the incidence of HPV-unrelated site HNSCC (10.4 per 100,000 in 1995 to 21.7 per 100,000 in 2009, APC 55.0, p < 0.0001) in Taiwan [19], the HPV detection rate in patients with oropharyngeal cancer was 16.4% (45/274) in a Taiwan study and estimated to be 13%–17% in another study; these values are much lower than those in Western countries [20], [21]. Because of early termination and funding restrictions, it was not feasible to retrospectively collect data and materials for HPV analysis of our patients, and similar distributions of oropharyngeal cancer in the 2 arms may not support the effect of HPV-related problems on the outcome. However, the low HPV prevalence may account for the lower 3-year OS of the ICT/CCRT (47%) and CCRT (58%) arms compared with that reported in Western literature (75%) [5], [6].

The PUL regimen was considered less intensive compared with PF and TPF, and it may result in a less favorable outcome. A general consensus that emerged from phase III ICT trials is that the TPF regimen is more active than PF and is the current standard ICT regimen for HNSCC [2], [3], [4]. However, randomized trials of CCRT preceded or not preceded by ICT TPF still have not yet supported the use of ICT [5], [6]. The 3-year OS of 60% in the CCRT arm was determined according to our historical cohort data and the available scientific literature when the study was designed, and a 3-year OS of 56.0% in the ICT/CCRT arm and 60.4% in the CCRT arm was achieved. The controversial role of ICT in the management of HNSCC may not be due to variations in the PF-based regimen; the biological disadvantages of ICT may be the essential obstacle to attaining superior outcomes. Furthermore, pharmacoethnic analyses demonstrated that studies in Asia revealed an approximate 19-fold higher risk of docetaxel-induced severe neutropenia compared with non-Asian studies [22]. The optimal TPF dosage in our patients warrants further investigation.

The major determinants for improving survival in HNSCC patients treated with sequential strategy mainly through CCRT [1]. CCRT preceded by ICT delivers a heavier therapeutic loading to patients. ICT may affect the compliance of patients or even preclude subsequent major therapy. Our multivariate analysis revealed that a radiation dose <70 Gy was an independent predictor of poorer OS, PFS, and LRC. In the intention-to-treat analysis, the percentage of patients not receiving the complete treatment protocol was 25% in the ICT/CCRT arm and 11% in the CCRT arm. The incidence of this negative effect was 20%–30% in the ICT/CCRT arm and 12% in the CCRT arm in phase III trials [2], [23], [24].

In addition to the preclusion of post-ICT RT, the CT regimen used for post-ICT CCRT is another concern in managing advanced HNSCC. Although various strategies including RT alone, CCRT with various CT regimens, and bio-RT with cetuximab have been used in the post-ICT TPF setting [2], [5], [6], [24], [25], [26], the optimal strategy, particularly a strategy with lower morbidity, requires further investigation. Cisplatin-based CCRT is the most commonly advised practice [7], [27]. The cutoff point of 200 mg/m2 for the accumulated dose of cisplatin during RT has been proposed to be a factor on OS in HNSCC by retrospective reviews [27], [28]. This proposition was also supported in our trial. An accumulated dose of cisplatin <150 mg/m2 (3 cycles of PUL) correlated with poorer PFS and LRC in multivariate analysis and was more common in the ICT/CCRT arm (46.8% vs 16.2%; p = 0.000). Although the issue of the cisplatin dose intensity during RT has not yet been proved by a precise trial, supportive care assisting patients in completing treatment per the established protocol is essential for favorable outcomes. The similar toxicity profiles during CCRT between the 2 arms might due to the nonadherence to the protocol occurred because of adverse events or poor patient compliance.

Neoadjuvant CT for advanced HNSCC management is controversial. Subgroup analysis of a phase III trial revealed a survival benefit in patients with unresectable disease [9]. In this trial, 36 patients had unresectable disease. Although an analysis of the entire population revealed poorer PFS and LRC in the ICT/CCRT arm, analysis of patients with unresectable disease revealed no difference in OS (p = 0.893), PFS (p = 0.629), LRC (p = 0.226), or DM (p = 0.817) between the study arms. Further investigation of ICT can focus on patients with unresectable disease who require early symptom management and function improvement before CCRT.

We acknowledge the limitations in our analysis; specifically, our results were confounded because of premature enrollment closure and an unbalanced distribution of hypopharyngeal primary tumors and N2 and N3 disease. We demonstrated that ICT/CCRT yielded similar OS to that of CCRT, but suboptimal post-ICT CCRT resulted in poorer PFS and LRC in patients treated with ICT. The ICT strategy should be restricted to patients with the potential to benefit, such as those with unresectable disease and candidates for organ preservation, and effort to support patients in completing RT or CCRT protocols is essential.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by grants CMRPG 360101-3 from the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2018.04.003.

Contributor Information

Joseph Tung-Chieh Chang, Email: jtchang@cgmh.org.tw.

Hung-Ming Wang, Email: whm526@cgmh.org.tw.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Pignon J.P., le Maitre A., Maillard E., Bourhis J., MACH-NC Collaborative Group Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vermorken J.B., Remenar E., van Herpen C., Gorlia T., Mesia R., Degardin M. Cisplatin, fluorouracil, and docetaxel in unresectable head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1695–1704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pointreau Y., Garaud P., Chapet S., Sire C., Tuchais C., Tortochaux J. Randomized trial of induction chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil with or without docetaxel for larynx preservation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:498–506. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lorch J.H., Goloubeva O., Haddad R.I., Cullen K., Sarlis N., Tishler R. Induction chemotherapy with cisplatin and fluorouracil alone or in combination with docetaxel in locally advanced squamous-cell cancer of the head and neck: long-term results of the TAX 324 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:153–159. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haddad R., O'Neill A., Rabinowits G., Tishler R., Khuri F., Adkins D. Induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy (sequential chemoradiotherapy) versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locally advanced head and neck cancer (PARADIGM): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:257–264. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen E.E.W., Karrison T., Kocherginsky M., Huang C.H., Agulnik M., Mittal B.B. DeCIDE: a phase III randomized trial of docetaxel (D), cisplatin (P), 5-fluorouracil (F) (TPF) induction chemotherapy (IC) in patients with N2/N3 locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl):5500. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forastiere A.A., Zhang Q., Weber R.S., Maor M.H., Goepfert H., Pajak T.F. Long-term results of RTOG 91-11: a comparison of three nonsurgical treatment strategies to preserve the larynx in patients with locally advanced larynx cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:845–852. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janoray G.P.Y., Garaud P., Chapet S., Alfonsi M., Sire C., Tuchais C. Long-term results of GORTEC 2000-01: a multicentric randomized phase III trial of induction chemotherapy with cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil, with or without docetaxel, for larynx preservation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(suppl):6002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zorat P.L., Paccagnella A., Cavaniglia G., Loreggian L., Gava A., Mione C.A. Randomized phase III trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in head and neck cancer: 10-year follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1714–1717. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H.M., Wang C.H., Chen J.S., Chang H.K., Kiu M.C., Liaw C.C. Cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil as neoadjuvant chemotherapy: predicting response in head and neck squamous cell cancer. J Formos Med Assoc. 1995;94:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H.M., Wang C.H., Chen J.S., Su C.L., Liao C.T., Chen I.H. Impact of oral submucous fibrosis on chemotherapy-induced mucositis for head and neck cancer in a geographic area in which betel quid chewing is prevalent. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22:485–488. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199910000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colevas A.D., Amrein P.C., Gomolin H., Barton J.J., Read R.R., Adak S. A phase II study of combined oral uracil and ftorafur with leucovorin for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 2001;92:326–331. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010715)92:2<326::aid-cncr1326>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nogue M., Saigi E., Segui M.A. Clinical experience with tegafur and low dose oral leucovorin: a dose-finding study. Oncology. 1995;52:167–169. doi: 10.1159/000227451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H.M., Wang C.S., Chen J.S., Chen I.H., Liao C.T., Chang T.C. Cisplatin, tegafur, and leucovorin: a moderately effective and minimally toxic outpatient neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 2002;94:2989–2995. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H.M., Hsueh C.T., Wang C.S., Chen I.H., Liao C.T., Tsai M.H. Phase II trial of cisplatin, tegafur plus uracil and leucovorin as neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx and hypopharynx. Anti Cancer Drugs. 2005;16:447–453. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200504000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H.M., Hsu C.L., Hsieh C.H., Fan K.H., Lin C.Y., Chang J.T. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy using cisplatin, tegafur, and leucovorin for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx and oropharynx. Biomed J. 2014;37:133–140. doi: 10.4103/2319-4170.117893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greene F.L., Page D.L., Fleming I.D., Fritz A.G., Balch C.M., Haller D.G. 6th ed. Springer-Verlag; New York (NY): 2002. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cancer staging manual. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bureau of Health Promotion DoH, The Executive Yuan, Taiwan, R.O.C . 2013. Cancer registry annual report 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang T.Z., Hsiao J.R., Tsai C.R., Chang J.S. Incidence trends of human papillomavirus-related head and neck cancer in Taiwan, 1995-2009. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:395–408. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Swiahb J.N., Huang C.C., Fang F.M., Chuang H.C., Huang H.Y., Luo S.D. Prognostic impact of p16, p53, epidermal growth factor receptor, and human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal cancer in a betel nut-chewing area. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:502–508. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Martel C., Ferlay J., Franceschi S., Vignat J., Bray F., Forman D. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:607–615. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yano R., Konno A., Watanabe K., Tsukamoto H., Kayano Y., Ohnaka H. Pharmacoethnicity of docetaxel-induced severe neutropenia: integrated analysis of published phase II and III trials. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18:96–104. doi: 10.1007/s10147-011-0349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hitt R., Grau J.J., Lopez-Pousa A., Berrocal A., García-Girón C., Irigoyen A. A randomized phase III trial comparing induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy alone as treatment of unresectable head and neck cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:216–225. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Posner M.R., Hershock D.M., Blajman C.R., Mickiewicz E., Winquist E., Gorbounova V. Cisplatin and fluorouracil alone or with docetaxel in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1705–1715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lefebvre J.L., Pointreau Y., Rolland F., Alfonsi M., Baudoux A., Sire C. Induction chemotherapy followed by either chemoradiotherapy or bioradiotherapy for larynx preservation: the TREMPLIN randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:853–859. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.3988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Group GIS A phase II-III study comparing concomitant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) versus cetuximab/RT (CET/RT) with or without induction docetaxel/cisplatin/5-fluorouracil (TPF) in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (LASCCHN): efficacy results ( NCT01086826) J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl):6003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen-Tan P.F., Zhang Q., Ang K.K., Weber R.S., Rosenthal D.I., Soulieres D. Randomized phase III trial to test accelerated versus standard fractionation in combination with concurrent cisplatin for head and neck carcinomas in the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0129 trial: long-term report of efficacy and toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3858–3866. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spreafico A.H.S., Xu W., Granata R., Liu C.S., Waldron J.N., Chen E. Differential impact of cisplatin dose intensity on human papillomavirus (HPV)-related (1) and HPV-unrelated (2) locoregionally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (LAHNSCC) J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(suppl):6020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.