Abstract

Background

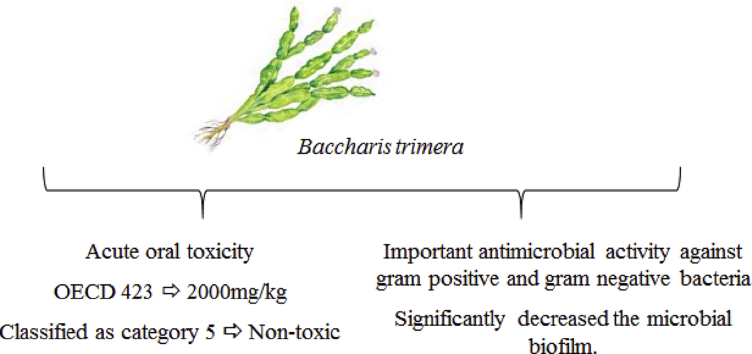

The present study aimed to evaluate the possible acute oral toxicity of Baccharistrimera leaf dye as well as its antimicrobial activity.

Method

Organization for Economic co-operation and development (OECD) 423 was used to assess acute oral toxicity and as per protocol a dose of 2000 mg/kg of tincture was administered to Wistar rats, male and female, and observed for 14 days. Biochemical and hematological analyzes were performed with sample collected of rat. The dye was evaluated for antimicrobial activity by agar diffusion and microdilution methods, which allow to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) and antibiofilm potential.

Results

The results showed that there was no loss of animals and no significant changes in hematological and biochemical parameters after oral administration of 2000 mg/kg of tincture and was considered safe by the OECD, classified as category 5. The dyeing also showed an important antimicrobial activity against gram positive and gram negative bacteria also significantly decreased the microbial biofilm.

Conclusion

The tincture of B.trimera leaf when given orally once can be considered safe and has a relevant antimicrobial potential that should be elucidated in subsequent research.

Keywords: Medicinal plants, Carqueja, Antimicrobial activity, Toxicity

Graphical abstract

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject:

Despite advances in studies for the use of medicinal plants, many people associate the natural origin of products with low toxicity and lack of drug interactions. This belief is considered erroneous, since the plants are xenobiotic and they undergo biotransformation in the human metabolism, being able to form toxic products.

What this study adds to the field:

Considering the wide variety of therapeutic indications and the popular use of the B. trimera species, the toxicological study and antimicrobial properties of this plant are relevant for a better knowledge of the effects caused, as well as the safety in the use of the same as a therapeutic resource.

Medicinal plants are misused because they are believed to be a natural product that do not cause toxic or adverse effects, and the popular use of plants by many communities and ethnic groups serves as validation of the effectiveness of these medicines. However, toxicological studies show that plants, in some cases and when used exacerbated, can be harmful or even, in high doses, lethal. The same plant can contain medicinal and therapeutic parts, and also parts with toxic substances harmful to human and animal organisms [1], [2].

The frequent appearance of resistant and multi-resistant strains to the usual antimicrobials and the investigation for low-side effect drugs have been contributed to the search for alternative treatments against diseases caused by microorganisms [3], [4]. An important public health problem are the nosocomial infections caused by strains resistant to available antibiotics by the pharmaceutical industry, which makes the search for new antimicrobial agents extremely important [5].

A plant belonging to the family Asteraceae, whose species has been identified in pharmacology articles as Baccharis trimera (Less.) DC or even Baccharis genistelloides var. Trimera (Less.) Baker (which are data of Baccharis crispa [6]. B. trimera (Less) DC) it is a small tree, found in rocky soils and sandy fields of southern Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina. In Brazil, it is popularly known a carqueja, carqueja-amarga, carqueja-do-mato, vassoura [7], [8]. Studies published about B. trimera describe analgesic [9], [10], muscle relaxant effects [11], antidiabetic [12], antioxidant [13], anti-inflammatory [14], [15] anthelmintic activity [16] and hepatotoxicity [17]. Silva et al. [8] studied the acute toxicity of B. trimera tincture, but only evaluated the mortality and classified the plant as category 5, relatively safe. In subacute toxicity, levels of the enzymes aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were reduced after 28 days of treatment at 200 and 400 mg/kg doses of B. trimera dye.

Studies demonstrate the antimicrobial activity of crude extract [18] and essential oil [19], [20] against Gram negative, Gram positive and fungi.

Considering its variety of therapeutic indications and its popular use, it is relevant to evaluate the detailed acute toxicity and antimicrobial activity of B. trimera tincture for a better knowledge of the effects caused by this plant, as well as the safety of its use as a therapeutic resource.

Materials and methods

Vegetable sample

The B. trimera tincture used in the experiments was purchased by Flores e Ervas Com. Fazenda Ltda. (Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil), in 2015, registered under the number NPT.0215/082 (Responsible Pharmaceutical: Karina da Silva). The B. trimera leafs were macerated and crushed with ethanol (68%) solution.

Animals

For the acute toxicity, Wistar adult rats, male and female, of 6 and 8 weeks of age, weighing 160–200 g, from Biotério Central da Universidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM) were used. The animals were separated according to sex and were acclimatized to the new environment for 5 days before the start of the experiment. All of the animals were housed on polypropylene cages, the environment temperature was kept at 24 °C ± 2 °C, and the relative humidity at 45–55%, with a light/dark cycle of 12:12 h. The rats were treated with commercial food and ad libitum water. The animals were manipulated and the experiments were performed with approval of the UFSM Ethics Committee (CEUA UFSM; protocol 050/2014).

Evaluation of acute toxicity

The acute oral toxicity of B. trimera tincture was evaluated in rats of both sexes, as preconized by the guidance of OCED (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development-423, approved in 17 of December of 2001) with modifications [21].

According to the guidance of OCED 423, these experiments were performed twice with the use of 3 animals of each sexual category by stage. The animals of the test group received a unique dose of 2000 mg/kg of B. trimera tincture, with the help of esophageal probe. The control group was treated by the same route with ethanol (68%) at a 10 mL/kg concentration. The dose used in the experiment of acute toxicity was chosen from dose 2000 mg/kg, as described in the OCED guide. According to the OCED 423 protocol, this assay was performed in two independent experiments to estimate the LD50. In total, 12 male and 12 female rats were used.

After the administration, the animals were individually observed during the first 30 min and daily. After that, the observation was extended for 14 days. The analysis included changes in skin, bristle, eyes and mucosa of respiratory tract, somatomotor activity and behavior. The attention was directed to the analysis of tremors, convulsion, salivation and diarrhea. The weight of each animal was determined just before administration of the substance of the study, and daily during all the experiment. At the 15th day, all animals were submitted to a short fasting of 8 h, were anesthetized with 50 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) of sodium pentobarbital, received 8 mg/kg i.p. of tramadol, and were euthanized by cardiac puncture.

Biochemical and hematological analysis

Blood was collected by cardiac puncture in two tubes: one with the anticoagulant ethylenediamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA), and the other without anticoagulant. The blood without anticoagulant was allowed to coagulate before the centrifugation (4000 rpm during 10 min) to obtain the serum, which was used to measure urea (URE), creatinine (CRE), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). The measurement was performed using commercial kit (Kits Diagnostico Laboratorial Bioclin/Quibasa, Minas Gerais, Brasil) and biochemical analyzer (Genz, Bioplus: Bio-2000). The blood with anticoagulant was immediately analyzed in search of hematologic parameters such as leukocytes (WBC) and its differentials (lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes and eosinophil's), erythrocytes (RBC), hemoglobin (HGB), hematocrit (HCT), average corpuscular volume (VCM), concentration of average corpuscular hemoglobin (CHCM), distribution in the size of red blood cells (RDW), platelets count (PLT), and proteins (PT) were determined with assistance of veterinary automatic counter Mindray BC 2800.

Antimicrobial activity

Microorganisms

The following microorganisms were used in the experiments: Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213), S. aureus (ATCC 6538), Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (Clinical isolate), Escherichia coli (ATCC 35218), Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 700603), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PAO1) and Candida albicans (ATCC 14053). The strains were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). These microorganisms were maintained on culture medium with glycerol and frozen at −80 °C. The samples were unfrozen, inoculated on Brain Heart Infusion broth (BHI), and incubated for 24 h. After that, they were seeded on Nutrient agar and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. From the grown colonies, the suspension in NaCl at 0.9% corresponding to the 0.5 at McFarland scale (1.5 × 108 CFU/mL) was produced.

Disk diffusion method

To evaluate the initial antimicrobial activity of B. trimera, the disk diffusion method was performed, as described previously by Bauer et al. [22]. The microorganisms were seeded in petri dishes with Mueller Hinton agar (MHA) and a disk with pure B. trimera tincture was added on the agar surface. Meropenem was used as control. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and, afterwards, the inhibition zones were measured in millimeters (mm). The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC)

The MIC was determined by microdilution method in 96 well-plates. Different concentrations of B. trimera tincture were added in wells with Mueller Hinton broth (MHB) and the suspension with microorganisms. Positive control was considered to be the well with only the suspension and MHB, while the negative control was only MHB. Afterwards, the plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. The assay was performed in triplicate. The assay was revealed with 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride, which develops a red color in the microbial grown. The lowest concentration that doesn't show change in color was considered as MIC. To determine the MBC, an aliquot of 1 μl was taken of each well, seeded on Nutrient agar plate and incubated for 24 h. Afterwards, the colonies were identified and the lowest concentration that did not demonstrated microbial growth was considered the MBC.

Biofilm formation and treatment with B. trimera tincture

The antibiofilm potential was evaluated against the strain P. aeruginosa PAO1. The method used to this assay was described previously [23] with modifications. To biofilm formation, fresh exponentially grown culture of P. aeruginosa was diluted to be 108 CFU/mL, and 20 μL was added to 96-well plates (Nunclon™ D surface, Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark), containing 100 μL of BHI broth. The plate was incubated in 37 °C for 24 h. After formation of the biofilm, the treatment was performed and incubated for 24 h in a condition of 37 °C, according to Manner et al. [24]. The treatment was performed with MIC and MBC of B. trimera (1.56% and 3.125%). A positive control was performed containing only BHI broth and the P. aeruginosa strain while the negative control was just BHI broth.

Quantification of biofilm biomass

The supernatant was removed and washed four times with distilled water, fixing with 95% of methanol and staining with 150 μL of 0.1% of crystal violet for 10 min at room temperature (RT). After incubation, the well-plates were washed with distilled water, and ethanol 95% was added to dissolve the coloring after 15 min. After that, 100 μL were transferred into another plate to measure spectrophotometrically at 570 nm to crystal violet in spectrophotometer (TP-Reader; ThermoPlate, Goiás, Brazil). The biofilm formation was determined by the difference between the mean optical density (OD) readings obtained in the positive control (BHI broth and P. aeruginosa strain) and the treatment with MIC/MBC of B. trimera tincture.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed in mean ± S.D. All results were submitted to analysis of variance (ANOVA) one-way followed by the Tukey test. For the comparison between the control and the treated group, the t test was used. The values were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was carried out using Statistic 7.0 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, USA) and Graph Pad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad, USA).

Results

Acute toxicity

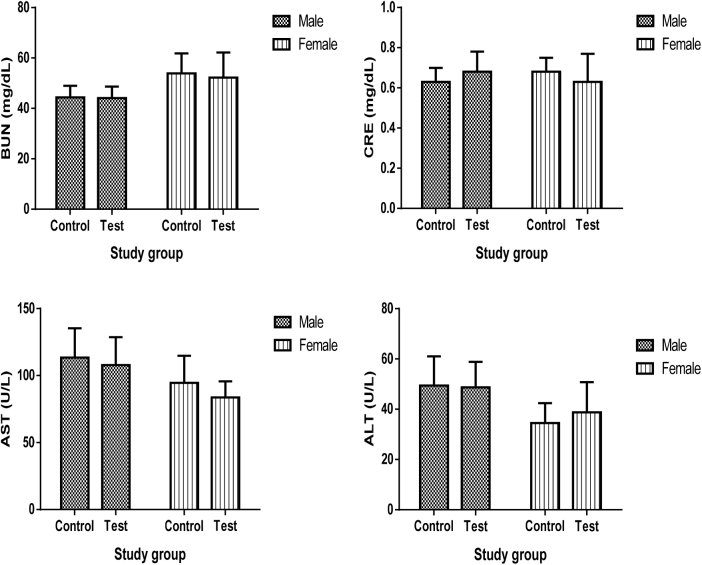

Oral administration of B. trimera tincture in rats of both sexes does not cause death. There is no observation of body weight gain, the animals did not show behavior changes during the study, and macroscopic changes in the organs were not found during the necropsy. Acute oral administration of B. trimera tincture, as summarized in Fig. 1, did not significantly (p < 0.05) change the biochemical parameters, and it is also apparent from Table 1, Table 2 that no significant alterations were observed in the various hematologic parameters.

Fig. 1.

Effects of acute administration of B. trimera tincture on biochemical parameters in male and female rats. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey test, when appropriate (n = 6). Abbreviations used: BUN: Blood urea nitrogen; CRE: creatinine; ASAT: aspartate aminotransferase; ALAT: alanine aminotransferase. Differences between the groups were considered to be significant when p < 0.05.

Table 1.

Effects of acute administration of B. trimera tincture on erythrocytic parameters and platelets levels in male and female rats.

| Sex | Study group |

2000 mg/kg | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | |||

| Male | RBC (x106/uL) | 7.77 ± 0.87 | 6.94 ± 1.46 |

| HBG (g/dL) | 15.72 ± 1.66 | 14.01 ± 3.16 | |

| HCT (%) | 46.87 ± 5.68 | 42.58 ± 6.25 | |

| MCV (fL) | 60.30 ± 1.94 | 60.06 ± 2.96 | |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 33.57 ± 1.22 | 33.53 ± 1.36 | |

| RDW (%) | 15.46 ± 0.42 | 15.73 ± 0.37 | |

| PLT (x103/uL) | 1067.87 ± 120.25 | 1176.00 ± 148.94 | |

| PT (g/dL) | 8.02 ± 0.75 | 7.84 ± 0.85 | |

| Female | RBC (×106/uL) | 7.68 ± 0.64 | 7.85 ± 0.35 |

| HBG (g/dL) | 15.34 ± 1.42 | 15.50 ± 0.70 | |

| HCT (%) | 47.50 ± 3.61 | 47.20 ± 2.36 | |

| MCV (fL) | 60.70 ± 2.10 | 59.38 ± 1.92 | |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 32.92 ± 0.73 | 33.26 ± 0.73 | |

| RDW (%) | 14.15 ± 0.78 | 13.96 ± 0.53 | |

| PLT (×103/uL) | 1228.78 ± 214.02 | 1269.00 ± 196.03 | |

| PT (g/dL) | 7.98 ± 0.35 | 8.05 ± 0.25 |

Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey test, when appropriate (n = 6). Abbreviations: RBC: Red Blood Cells counts; HGB: Hemoglobin; HCT: Hematocrit; MCV: Mean Corpuscular Volume; MCHC: Mean Cell Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration; RDW: Red cells Distribution Width; PLT: Platelet; PT: Proteins. Differences between groups were considered to be significant when p < 0.05.

Table 2.

Effects of acute administration of B. trimera on leukocytes and its differential count in male and female rats.

| Sex | Study group |

2000 mg/kg | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | |||

| Male | WBC (×103/uL) | 12.38 ± 3.84 | 10.95 ± 2.71 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 75.70 ± 9.95 | 78.80 ± 5.83 | |

| Neutrophils (%) | 18.50 ± 7.78 | 18.40 ± 6.70 | |

| Monocytes (%) | 4.50 ± 3.20 | 4.30 ± 3.65 | |

| Eosinophils (%) | 1.30 ± 1.50 | 1.50 ± 1.26 | |

| Female | WBC (×103/uL) | 7.98 ± 0.85 | 8.08 ± 1.00 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 76.33 ± 8.53 | 72.87 ± 9.37 | |

| Neutrophils (%) | 18.85 ± 3.93 | 20.33 ± 3.44 | |

| Monocytes (%) | 3.55 ± 2.24 | 5.00 ± 3.54 | |

| Eosinophils (%) | 1.00 ± 0.76 | 1.12 ± 0.83 |

Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey test, when appropriate (n = 6). Abbreviation: WBC: white blood cell. Differences between groups were considered to be significant when p < 0.05.

Antimicrobial activity

After incubation, diameters of the growth inhibition zone were measured, and the results are expressed in mm (Table 3). The tincture showed an important antimicrobial activity against Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Table 3.

Diameter of inhibition zone of B. trimera tincture against tested microorganisms.

| Microorganism | Zone diameter (mm) B. trimera tincture | Zone diameter (mm) Control (Meropenem) |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus (ATCC 29213) | 9 ± 1 | 48 |

| S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | 12 ± 2 | 50 |

| MRSA (Clinical isolate) | 12 ± 2 | N/A |

| E. coli (ATCC 35218) | N/A | 42 |

| K. pneumoniae (ATCC 700603) | 11 ± 1 | 16 |

| P. aeruginosa (PAO1) | 7 ± 1 | 26 |

| C. albicans (ATCC 14053) | N/A | 19 |

Abbreviation: N/A: Not applicable. N = 5.

Minimal inhibitory concentration and minimal bactericidal concentration

After adding the revealing substance, the MIC was visualized and showed 0.78% as the lowest concentration and 6.25% as the highest concentration. The MBC method demonstrated a bactericidal effect from 12.5 until 1.56% (Table 4).

Table 4.

MIC and MBC of B. trimera tincture against tested microorganisms.

| Microorganisms | MIC (mg/mL) | MBC (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus (ATCC 29213) | 6.56 | 13.125 |

| S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | 6.56 | 13.125 |

| MRSA (Clinical isolate) | 6.56 | 26.25 |

| K. pneumoniae (ATCC 700603) | 52.5 | 105 |

| P. aeruginosa (PAO1) | 13.125 | 26.25 |

Abbreviations: MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration; MBC: minimum bactericidal concentration. N = 5.

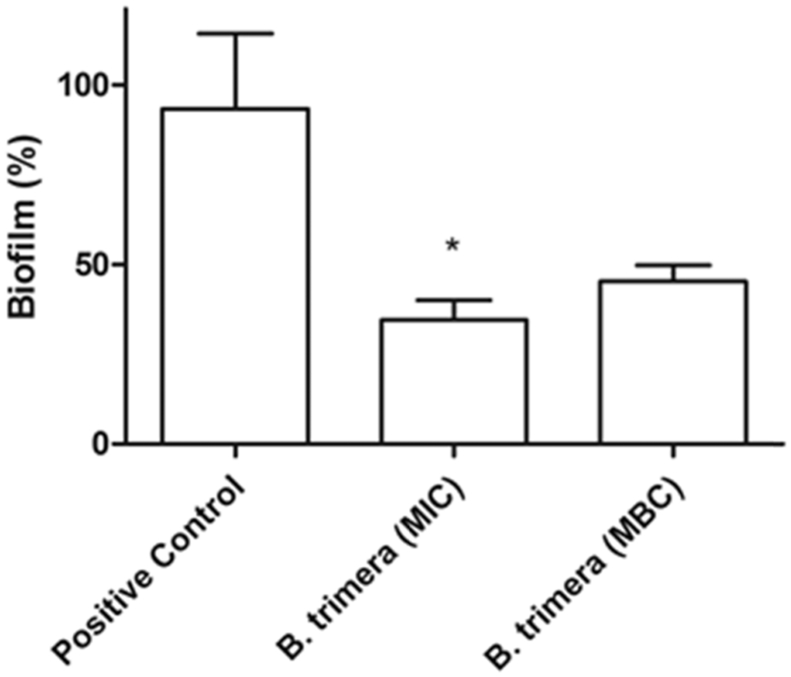

Quantification of biofilm biomass

After the treatment, the crystal violet assay showed a decrease of 65% of biofilm biomass when treated with MIC of B. trimera. While the biofilm treated with MBC showed a decrease of 45% (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Antibiofilm activity of B. trimera tincture against P. aeruginosa PAO1. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, followed by Tukey test considering values p < 0.05 statistically significant compared with Positive Control (n = 5). Data expressed on mean ± S.D. Absorbance at 570 nm.

Discussion

The OECD Guide 423 does not allow the calculation of an LD50, however, this protocol is the appropriate procedure when few animals (n = 3) are used. Depending on the mortality and/or moribund state of the animals, an average of 2–4 steps may be required to allow assessment of the acute toxicity of the test substance. Thus, according to guide 423, in an acute toxicity test in which no death occurs in more than one of the six animals treated at a dose of 2000 mg Dear reviewer, as we discuss the results shortly after they are written in the Discussion item, we believe that there will be a de-structuring of our text if we put an initial paragraph as suggested. In this way, we prefer to keep believing that you accept our decision./kg, the LD50 value may be considered to be greater than 2000 mg/kg and lower than 5000 mg/kg, and the compound is classified in category 5 [21].

The Acute Toxicity Guide 423 describes that only the use of females is necessary [21]. On the other hand, the “Guide for performing preclinical toxicity studies of herbal remedies” recommends that both sexes are tested with a number of six animals per genus and only one animal species [24]. The use of only three animals per genus allowed to estimate the LD50 of guide 423, and the use of alternative methods to estimate the LD50 of herbal medicines in Brazil is not restricted [21], [25].

Silva et al. [8] analyzed only mortality and toxicity signals after the administration of B. trimera tincture. Their experiment showed results that corroborate with the present study. Analyzing the diversity of pharmacological effects found on medicinal plants, the studies that evaluate the safety and efficacy of these plants were considered of great importance for the scientific community, becoming a frequent focus on the researches.

The analysis of blood parameters is a pertinent method to evaluate the risk of toxicity on tested animals, and thus posterior use of compounds by people [25], [26]. The first organs which show toxicity symptom when exposed to toxic substances are kidney and liver. Urea and creatinine, can be used as biomarkers of kidney lesion. Aminotransferases, such as ALT and AST, are considered indicative of hepatic damage [8], [27], [28]. The studied biochemicals parameters were not modified in rats of both sexes treated with B. trimera when compared with the control group, indicating a normal function of kidney and liver.

The hematopoietic system is one of the most susceptible targets to toxic substances, and it is an important parameter to evaluate the physiologic and pathologic state in humans and animals [26], [28]. The laboratory study of the red series is composed of several tests, which are called an erythrogram. The analysis of this great laboratory tool is able to inform the conditions of the gas transport system; they indicate situations of nutritional deficiency, drug production, increased destruction or other blood loss and diagnostic anemia [29]. The leukogram in which a percentage of leukocytes cells (also known defense cells) is considered important information, not only for the diagnosis of diseases, but also as a “health certificate” in periodical exams, or check-ups [26], [27], [29]. Although the platelets are very small, they play an important role in the hemostasis. They help to start the blood coagulation after damage in blood vessels. Therefore, platelets count can be used to investigate and evaluate some hemorrhagic disturbs and disturbs of coagulation [27], [29]. In relation to the results of our study, such as leukocytes and the differential, the mean of score values of the treated groups with a unique dose of tincture remained in the normal intervals in comparison with the control group. The mean values of red series and platelets also didn't show significant difference when comparing the control with to the treated groups of both sexes.

The results found in our study of acute toxicity of B. trimera dye were obtained at a dose that, although high, was only as high as convenient for the objectives and protocol used. However, the evaluation of chronic toxicity, the action mechanism, and other organs should be studied.

Actually, one of the biggest concerns associated to infectious disease is microbial resistance. The usual drugs do not follow the microbial evolution and, in this context, there is a lack of therapeutic alternatives for infections caused by multiresistant microorganisms. Thus, the search of new options is becoming more frequent [30], [31].

The term biofilm describes the irreversible adhesion of microbial agglomerates (bateria, fungi, protozoa and viruses) on biological or synthetic surfaces as implants, tissues, bones, teeth also many medical devices [32], [33]. These agglomerates produce a polymeric extracellular matrix which prevents the penetration of microbial agents increasing the resistance. Moreover, the biofilms are usually in place of difficult access, making the treatment rarely effective, generating costs and decreasing the patient's quality of life [34], [35], [37].

According to da Silva and de Souza [37], among the methods for the evaluation of antimicrobial activity, the disk diffusion method and the bioautography stand out. This last one is considered a technique of easy execution and low cost for the identification of inhibitory activity, being an efficient assay sensible in the determination of antimicrobial activity, because it is used at a lower rate than the 2.5 μg of the tested compound for the formation of an inhibition zone [35], [36].

The property of curing wounds of B. trimera suggested a possible antimicrobial activity [38]. Different extracts were made as previously described and screened, and demonstrated activity against Bacillus subtilis, Micrococcus luteus and S. aureus. Previous studies demonstrated antifungal activity of Baccharis extract against Paracoccidiodes brasiliensis [39]. The present antimicrobial experiments showed the potential of the tincture against both Gram positive and negative bacteria. The tincture demonstrated to be effective against resistant bacteria such as K. pneumoniae β-lactamase producer and S. aureus resistant to methicillin. Moreover, the B. trimera tincture was able to inhibit a biofim forming bacteria like P. aeruginosa (PAO1). In view of this last finding, the antibiofilm activity of the tincture was evaluated. This is the first study concerning the antibiofilm potential of B. trimera. The experiment demonstrated the reduction of formed biofilm after the treatment with tincture at MIC and MBC concentrations. This finding is of great relevance in view of the difficulty of treatments that combat biofilm. However, the use of B. trimera in biological environment as an option for the multiresistant infections requires toxicological tests to clarify the mechanisms of action and effects of this tincture.

The high content of phenols and flavonoids may be recognized by antibacterial properties. The antimicrobacterial activity of these compounds is well described in the literature [40], [41]. This work could be explained by the great amount of rutin, quercetin and kaempferol present in B. trimera tincture as evaluated by Silva [8] in his study, which corroborates the antimicrobial results found in our study.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that the tincture of B. trimera leafs shows an antimicrobial potential. The toxicological evaluation revealed that the tincture doesn't show significant toxicity when only one oral dose in animals of both sexes was administered, being considered safe by OCDE, classified as 5 category, which, in addition to the fact that the pharmacological effects of B. trimera have already being proven, makes this plant an excellent candidate for the development of a future herbal medicine.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The financial support provided by CAPES, CNPQ, and Bioclin/Quibasa is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Lulekal E., Asfaw Z., Kelbessa E., Van Damme P. Ethnomedicinal study of plants used for human ailments in Ankober District, North Shewa zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9:63. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silveira P.F., Bandeira M.A.M., Arrais P.S.D. Pharmacovigilance and adverse reactions to the medicinal plants and herbal drugs: a reality. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2008;18:618–626. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clardy J., Fischbach M.A., Walsh C.T. New antibiotics from bacterial natural products. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1541–1550. doi: 10.1038/nbt1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jorgetto G.V., Boriolo M.F.G., Silva L.M., Nogueira D.A., José T.D.S., Ribeiro G.E. Analysis on the in vitro antimicrobial activity and in vivo mutagenicity by using extract from Vernonia polyanthes Less (Assa-peixe) Rev Inst Adolfo Lutz. 2011;70:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereira C.A.P., Marra A.R., Camargo L.F.A., Pignatari A.C.C., Sukiennik T., Behar P.R.P. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in brazilian pediatric patients: microbiology, epidemiology, and clinical features. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Besten M.A., Nunes D.S., Wisniewski A., Jr., Sens S.L., Granato D., Simionatto E.L. Chemical composition of volatiles from male and female specimens of Baccharis trimera collected in two distant regions of southern Brazil: a comparative study using chemometrics. Quim Nova. 2013;36:1096–1100. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grance S.R.M., Teixeira M.A., Leite R.S., Guimarães E.B., de Siqueira J.M., Filiu W.F.O. Baccharis trimera: effect on hematological and biochemical parameters and hepatorenal evaluation in pregnant rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;117:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silva A.R.H., Reginato F.Z., Guex C.G., Figueredo K.C., Araldi I.C.C., de Freitas R.B. Acute and sub-chronic (28 days) oral toxicity evaluation of tincture Baccharis trimera (Less) Backer in male and female rodent animals. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2016;74:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gené R.M., Cartaña C., Adzet T., Marín E., Parella T., Cañigueral S. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity of Baccharis trimera: identification of its active constituents. Planta Med. 1996;62:232–235. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul E.L., Lunardelli A., Caberlon E., de Oliveira C.B., Santos R.C., Biolchi V. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of Baccharis trimera aqueous extract on induced pleurisy in rats and lymphoproliferation in vitro. Inflammation. 2009;32:419–425. doi: 10.1007/s10753-009-9151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torres L.M.B., Gamberini M.R., Roque N.F., Lima-Landman M.T., Souccar C., Lapa A.J. Diterpene from Baccharis trimera with a relaxant effect on rat vascular smooth muscle. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:617–619. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliveira A.C.P., Endringer D.V., Amorim L.A.S., Brandão M.G.L., Coelho M.M. Effect of the extracts and fractions of Baccharis trimera and Syzygium cumini on glycaemia of diabetic and non-diabetic mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102:465–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borella J.C., Duarte D.P., Novaretti A.A.G., Jr., Menezes A., França S.C., Rufato C.B. Seasonal variability in the content of saponins from Baccharis trimera (Less.) DC (Carqueja) and isolation of flavone. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2006;16:557–561. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nogueira N.P.A., Reis P.A., Laranja G.A.T., Pinto A.C., Aiub C.A.F., Felzenszwalb I. In vitro and in vivo toxicological evaluation of extract and fractions from Baccharis trimera with anti-inflammatory activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;138:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Oliveira C.B., Comunello L.N., Lunardelli A., Amaral R.H., Pires M.G., da Silva G.L. Phenolic enriched extract of Baccharis trimera presents anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities. Molecules. 2012;17:1113–1123. doi: 10.3390/molecules17011113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Oliveira R.N., Rehder V.L.G., Oliveira A.S.S., Jeraldo V.L.S., Linhares A.X., Allegretti S.M. Anthelmintic activity in vitro and in vivo of Baccharis trimera (Less) DC against immature and adult worms of Schistosoma mansoni. Exp Parasitol. 2014;139:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lívero F.A.R., Martins G.G., Telles J.E.Q., Beltrame O.C., Biscaia S.M.P., Franco C.R.C. Hydroethanolic extract of Baccharis trimera ameliorates alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Chem Biol Interact. 2016;260:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aleixo A.A., Herrera K.M.S., Ribeiro R.I.M.A., Lima L.A.R.S., Ferreira J.M.S. Antibacterial activity of Baccharis trimera (Less.) DC. (carqueja) against bacteria of medical interest. Rev Ceres. 2013;60:731–734. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moura G.S., Franzener G., Stangarlin J.R., Schwan-Estrada K.R.F. Atividade antimicrobiana e indutora de fitoalexinas do hidrolato de carqueja [Baccharis trimera (Less.) DC.] Rev Bras Plantas Med. 2014;16(2, Suppl. 1):309–315. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki E.Y., Caneschi C.A., Forchat R.C., Brandão M.A.F., Raposo N.R.B. Antimicrobial activity of essential oil from Baccharis trimera (Less.) DC. (carqueja-amarga) Rev Cubana Plantas Med. 2016;21:346–358. [Google Scholar]

- 21.OECD- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development . OECD; Paris: 2001. Guideline 423: Acute oral toxicity-acute toxic class method; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer A.W., Kirby W.M., Sherris J.C., Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;45:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopes L.Q., Santos C.G., de Almeida Vaucher R., Gende L., Raffin R.P., Santos R.C. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of glycerol monolaurate nanocapsules against american foulbrood disease agent and toxicity on bees. Microb Pathog. 2016;97:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manner S., Skogman M., Goeres D., Vuorela P., Fallarero A. Systematic exploration of natural and synthetic flavonoids for the inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:19434–19451. doi: 10.3390/ijms141019434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonçalves N.Z., Lino J.R.R.S., Rodrigues C.R., Rodrigues A.R., Cunha L.C. Acute oral toxicity of Celtis iguanaea (Jacq.) Sargent leaf extract (Ulmaceae) in rats and mice. Rev Bras Plantas Med. 2015;17:1118–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dicson S.M., Samuthirapandi M., Govindaraju A., Kasi P.D. Evaluation of in vitro and in vivo safety profile of the Indian traditional medicinal plant Grewia tiliaefolia. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015;73:241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ezeja M.I., Anaga A.O., Asuzu I.U. Acute and sub-chronic toxicity profile of methanol leaf extract of Gouania longipetala in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151:1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Traesel G.K., de Souza J.C., de Barros A.L., Souza M.A., Schmitz W.O., Muzzi R.M. Acute and subacute (28 days) oral toxicity assessment of the oil extracted from Acrocomia aculeata pulp in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014;74:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grotto H.Z.W. Blood cell analysis: the importance for biopsy interpretation. Rev. Bras. Hematol. Hemoter. 2009;31:178–182. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boucher H.W., Talbot G.H., Bradley J.S., Edwards J.E., Gilbert D., Rice L.B. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! an update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kallen A.J., Mu Y., Bulens S., Reingold A., Petit S., Gershman K. Active bacterial core surveillance (ABCs) MRSA Investigators of the emerging infections program, health care-associated invasive MRSA infections, 2005-2008. JAMA. 2010;304:641–648. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de la Fuente-Núñez C., Reffuveille F., Fernández L., Hancock R.E. Bacterial biofilm development as a multicellular adaptation: antibiotic resistance and new therapeutic strategies. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16:580–589. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao G., Lange D., Hilpert K., Kindrachuk J., Zou Y., Cheng J.T. The biocompatibility and biofilm resistance of implant coatings based on hydrophilic polymer brushes conjugated with antimicrobial peptides. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3899–3909. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forier K., Raemdonck K., De Smedt S.C., Demeester J., Coenye T., Braeckmans K. Lipid and polymer nanoparticles for drug delivery to bacterial biofilms. J Control Release. 2014;190:607–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamilvanan S., Venkateshan N., Ludwig A. The potential of lipid- and polymer-based drug delivery carriers for eradicating biofilm consortia on device-related nosocomial infections. J Control Release. 2008;128:2–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen C.W., Hsu C.Y., Lai S.M., Syu W.J., Wang T.Y., Lai P.S. Metal nanobullets for multidrug resistant bacteria and biofilms. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;78:88–104. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silva A.G.C., de Souza T.D. Atividade antifúngica in vitro de metabólitos secundários produzidos por Bacillus cereus. Rev da Univ Val do Rio Verde. 2016;14:522–529. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bandoni A.L., Medina J.E., Rondina R.V.D., Coussio J.D. Genus Baccharis L. I: phytochemical analysis of a non polar fraction from B. Crispa Sprengel. Planta Med. 1978;34:328–331. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johann S., Cisalpino P.S., Watanabe G.A., Cota B.B., de Siqueira E.P., Pizzolatti M.G. Antifungal activity of extracts of some plants used in Brazilian traditional medicine against the pathogenic fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Pharm Biol. 2010;48:388–396. doi: 10.3109/13880200903150385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cantrell C.L., Franzblau S.G., Fischer N.H. Antimycobacterial plant terpenoids. Planta Med. 2001;67:685–694. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boligon A.A., Piana M., Kubiça T.F., Mario D.N., Dalmolin T.V., Bonez P.C. HPLC analysis and antimicrobial, antimycobacterial and antiviral activities of Tabernaemontana catharinensis A. DC. J Appl Biomed. 2005;13:7–18. [Google Scholar]