Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of combined treatment with the long-acting 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor-3 antagonist, palonosetron, the neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist, oral aprepitant, and dexamethasone as primary antiemetic prophylaxis for cancer patients receiving highly emetogenic cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Methods

Chemotherapy-naïve patients received the triple combination of palonosetron (0.25 mg), aprepitant (125 mg on day 1 and 80 mg on days 2 and 3), and dexamethasone (20 mg) from the beginning of highly emetogenic chemotherapy with cisplatin-based (≥50 mg/m2) regimens. The primary endpoint was a complete response (no emetic episodes and no rescue antiemetics) during the days 1–6.

Results

Sixty-nine hospitalized patients receiving chemotherapy from September 2012 to October 2014 were analyzed. Complete response of vomiting and nausea-free was achieved in 97.1% and 85.5% of patients in the first cycle, respectively, and 96.7% and 83.6% of patients in the second cycle, respectively. Common adverse events in all 69 patients included constipation (43%), hiccup (26%), and headache (4%).

Conclusion

The combination of palonosetron, aprepitant, and dexamethasone as primary antiemetic prophylaxis for cancer patients with highly emetogenic cisplatin-based chemotherapy is effective.

Keywords: Anti-emesis, Aprepitant, Chemotherapy, Cisplatin, Palonosetron

At a glance commentary

Scientific background of the subject

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting because of cisplatin-based chemotherapy strongly affects the quality of life of cancer patients. Primary antiemetic prophylaxis with the first-generation 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor-3 antagonist plus dexamethasone still resulted in about 20% patients experiencing acute and/or delayed emesis during the first cycle of cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

What this study adds to the field

The triple combination of palonosetron, aprepitant, and dexamethasone as primary antiemetic prophylaxis is safe and highly effective in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in the days following administration of highly emetogenic cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Nearly, all the patients experienced no episodes of vomiting and good control of nausea was maintained following chemotherapy.

Clinicians should be aware that chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) remains one of the most feared side effects of chemotherapy. CINV as a consequence of cisplatin-based chemotherapy strongly affects the quality of life for cancer patients [1], [2]. According to recent international guidelines [3], [4], cisplatin-based (at dose of ≥50 mg/m2) regimens are considered to be highly emetogenic forms of chemotherapy (HEC), with a >90% risk of inducing CINV [5].

The first-generation 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor-3 antagonist (5-HT3RAs), ondansetron, granisetron, dolasetron, and tropisetron, have provided significant improvement in the management of acute CINV [6] but have been shown to be ineffective in controlling delayed CINV, even when administered in multiple doses 24 h or more following chemotherapy [7]. Palonosetron is a novel, potent, selective second-generation 5-HT3RA with a longer half-life (40 h) [8], and a higher receptor binding affinity (>30-fold) with respect to other 5-HT3RAs [9]. The superiority of single-dose palonosetron (0.25 mg IV) over single-dose ondansetron (32 mg IV) or dolasetron (100 mg IV) for the prevention of emesis and delayed nausea has been demonstrated in phase III comparative trials [10], [11], [12], [13]. Aprepitant, the first approved substance P/neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptor antagonist (NK1RA), has been shown to significantly improve the prevention of acute and delayed CINV following HEC [14]. A 3-day oral aprepitant regimen in combination with standard antiemetics (ondansetron plus dexamethasone) was shown to offer enhanced protection against emesis associated with anthracycline- and cyclophosphamide-based breast cancer regimens or cisplatin-based HEC when compared with standard antiemetics alone [15], [16]. All antiemetic guidelines are unanimous in recommending a combination of aprepitant, dexamethasone, and a 5-HT3RA within the first 24 h for acute CINV with HEC [3], [4], [17].

In a previous study [18], we investigated the efficacy of adding aprepitant as a secondary antiemetic prophylaxis for cases in which a first-generation 5-HT3RA plus dexamethasone failed to achieve full antiemetic protection during the first cycle of a cisplatin-based regimen. Approximately 20% of patients receiving primary antiemetic prophylaxis with granisetron plus dexamethasone experienced acute and/or delayed emesis during the first cycle of cisplatin-based chemotherapy. The addition of aprepitant as a secondary antiemetic prophylaxis in subsequent cycles provided about 70% complete emesis protection in patients who failed primary prophylaxis. On the basis of these results, the aim of this prospective study was to evaluate the efficacy of a combination of the long-acting palonosetron, 3-day aprepitant and dexamethasone as primary antiemetic prophylaxis in patients receiving HEC (cisplatin ≥50 mg/m2), and to determine whether the antiemetic efficacy of the triple combination could be sustained.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients were enrolled in the study consecutively, and data were collected prospectively. All chemo-naïve patients in this study were scheduled to receive chemotherapy with a dose of at least 50 mg/m2 cisplatin followed immediately by a continuous infusion of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) with or without other chemotherapeutic agents. Cisplatin was given on day 1 and the other drugs on day 1 and subsequent days. Participants were required to be at least 18 years of age, with no prior history of cisplatin-containing chemotherapy, and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status grades of 0–3. Individuals with a concurrent severe illness, nausea, or vomiting in the period 24 h before chemotherapy, other known causes of nausea, or vomiting (e.g., central nervous system metastases, gastrointestinal obstruction, and hypercalcemia), or concurrent therapy with corticosteroids or benzodiazepines (unless given for night sedation) were excluded from the study. Demographic data and patient characteristics were examined and reported as frequencies and percentages [Table 1]. All patients were hospitalized during the administration of chemotherapy. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (IRB No.: 103-3856B).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 69).

| Variable | Study population |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Median (range) | 61 (32–81) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 42 (61) |

| Female | 27 (39) |

| Performance status, n (%) | |

| 0, 1 | 63 (91) |

| 2 | 2 (3) |

| 3 | 4 (6) |

| Primary site of malignancy, n (%) | |

| Head and neck | 2 (3) |

| Lung | 1 (1) |

| Breast | 2 (3) |

| Esophageal | 18 (26) |

| Genitourinary | 46 (67) |

| Chemotherapy regimen, dose (mg/m2), and days | |

| F500D1-2/L30-35D1-2/G1000/P50 | 39 (57) |

| F500D1-2/L30-35D1-2/E100/P50 | 1 (1) |

| F500D1-2/L30-35D1-2/V30/P50 | 4 (6) |

| F500D1-2/L30-35D1-2/P50 | 7 (10) |

| FP | 18 (26) |

| F1000D1-4/P100 | 1 |

| F1000D1-4/P75 | 14 |

| F1000D1-3/P75 | 1 |

| F1000D1-3/P60 | 1 |

| F660D1-4/P50 | 1 |

Abbreviations: F: 5-fluorouracil; L: Leucovorin; P: Cisplatin; E: Etoposide; G: Gemcitabine; V: Vinorelbine; D: Day.

Antiemetic therapy

This was a single-institution study. The same chemotherapeutic drug was used at identical doses during each treatment cycle. Each chemotherapy cycle consisted of cisplatin (50–100 mg/m2), and 20% mannitol (100–150 mL) administered in 500 mL of normal saline for 3 h. Palonosetron (Aloxi, Pierre Fabre, Medicament Production Aquitaine Pharm International, Idron, France) 0.25 mg in 100 mL of normal saline was given as a 30-min intravenous infusion before cisplatin administration. Oral aprepitant (Emed, Merck Sharp, and Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck and Co., Inc., PA, USA) was administered once daily on day 1 at a dose of 125 mg, and at 80 mg on days 2 and 3. Intravenous dexamethasone (20 mg) was administered before cisplatin or in solution with cisplatin. In addition, all the patients received intravenous dexamethasone (5 mg) every 12 h following cisplatin administration. Dexamethasone was discontinued after the completion of chemotherapy. Intramuscular diphenhydramine (30 mg) or intravenous metoclopramide (9 mg) was given to patients every 6 h as needed for an antiemetic rescue.

Response assessment and statistical analysis

Data on vomiting and nausea were recorded daily by the investigators (physicians and special nurses), commencing at the time of patient admission. In addition, the patients were asked to self-record their own symptoms daily during the days after discharge. These records were collected in the out-patient department or upon next admission. We recorded whether or not each patient experienced CINV and the severity of any episodes of CINV. A vomiting episode was defined as involuntary, forceful expulsion of stomach contents through the mouth. The efficacy of therapy on vomiting was defined as follows: Complete response (no emetic episodes and no rescue antiemetics); major response (1–2 emetic episodes); minor response (3–5 emetic episodes); and failure to response (>5 emetic episodes) [19], [20]. A nausea episode was defined as a stomach distress with distaste for food and an urge to vomit. The severity of nausea was rated by patients as none, mild (no interference with daily life), moderate (some interference with daily life), and severe (bedridden because of nausea). The analysis of vomiting and nausea was performed separately for day 1 (acute episodes) and days 2–6 (delayed episodes). The severity of delayed vomiting was based on the highest occurrence of emetic episodes between days 2 and 6, and the intensity of delayed nausea was recorded as the worst nausea experienced over the same period.

The primary endpoint was complete response during the 6-day study period. The secondary endpoints were the responses to treatment of acute and delayed emesis, and the severity of acute and delayed nausea. Adverse events were recorded. All data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Sixty-nine chemotherapy-naïve patients were analyzed consecutively from September 2012 to October 2014 at Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. This study population consisted of 42 men and 27 women, ranging in age from 32 to 81 years (median, 61 years). Most patients had stage IV disease (81%) and ECOG performance status grades from 0 to 2 (94%). More than half of our patients had primary malignancies of the genitourinary system, including the bladder, ureter, renal pelvis, and kidney. Detailed patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. All the patients received chemotherapy containing a cisplatin-based HEC regimen (cisplatin ≥50 mg/m2), and all were undergoing concurrent treatment with other emetogenic drugs: 5-fluorouracil (100%), gemcitabine (57%), vinorelbine (6%), etoposide (1%). Totally, 38% of patients took anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, hypnotics or sedatives for insomnia, depressive disorder, or anxiety disorder.

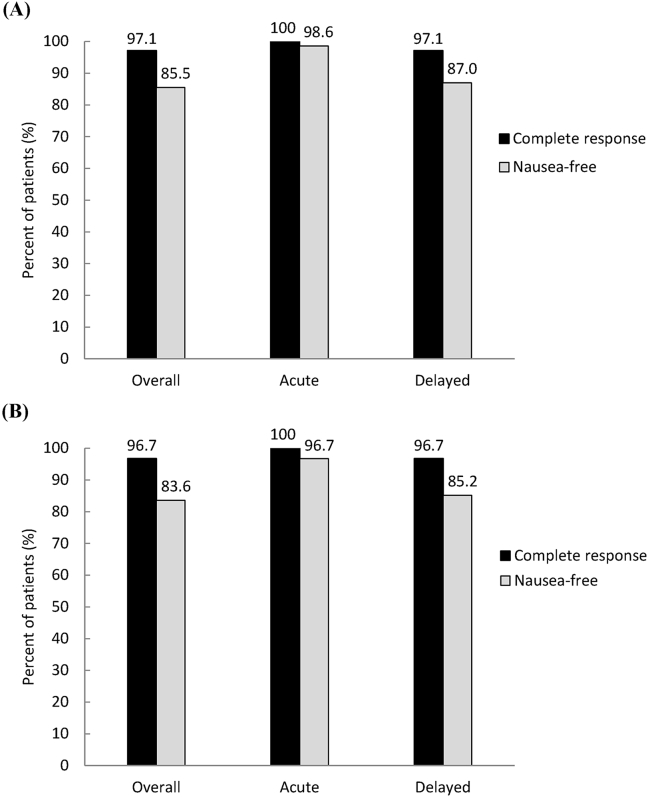

All of the 69 patients who received palonosetron, aprepitant, and dexamethasone for primary prophylaxis from emesis were evaluated in the first cycle of chemotherapy. The efficacy endpoints are summarized in Table 2, Table 3, Fig. 1. The antiemetic efficacy data in the first cycle are listed in Table 2 and Fig. 1A. Complete protection from acute vomiting and nausea was achieved in 100% and 98.6% of patients, respectively. Furthermore, complete protection from delayed vomiting and nausea was obtained in 97.1% and 87.0% of patients, respectively. Delayed nausea ratings of none and mild were obtained in 97.1% of patients. Overall, the complete response of vomiting and nausea-free was achieved in 97.1% and 85.5% of patients, respectively [Fig. 1A].

Table 2.

Incidence of CINV during the first chemotherapy.

| Response | Va |

Vd |

Response | Na |

Nd |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Complete response | 69 | 100 | 67 | 97.1 | None | 68 | 98.6 | 60 | 87.0 |

| Major response | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Mild | 1 | 1.4 | 7 | 10.1 |

| Minor response | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.9 | Moderate | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.9 |

| Failure to response | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Severe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviations: Va: Acute vomiting; Vd: Delayed vomiting; Na: Acute nausea; Nd: Delayed nausea; CINV: Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

Table 3.

Incidence of CINV during the second chemotherapy.

| Response | Va |

Vd |

Response | Na |

Nd |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Complete response | 61 | 100 | 59 | 96.7 | None | 59 | 96.7 | 52 | 85.2 |

| Major response | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3.3 | Mild | 2 | 3.3 | 8 | 13.1 |

| Minor response | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Moderate | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.7 |

| Failure to response | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Severe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviations: Va: Acute vomiting; Vd: Delayed vomiting; Na: Acute nausea; Nd: Delayed nausea; CINV: Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the percentages of patients who achieved complete response (no emesis and no rescue therapy), and nausea-free (none of nausea) during the overall study period (days 1–6), the acute phase (day 1), and the delayed phase (days 2–6) in the first (A) and the second (B) cycles of chemotherapy.

We planned for all the patients to receive two or more cycles of chemotherapy, and the majority (88.4%) completed the planned therapeutic scheme. Of the 69 patients who received palonosetron, aprepitant, and dexamethasone for primary emetic prophylaxis, 61 were evaluated in the second cycle of chemotherapy. The other eight patients were not evaluated for the following reasons: Not yet the time for the second cycle of chemotherapy (n = 4), progression or death due to neoplasm (n = 2), refusal of chemotherapy due to side effects (n = 1), or lost to follow-up (n = 1). Two patients reduced 20–25% of the dose of cisplatin due to mild to moderate delayed nausea in the first cycle of chemotherapy. The antiemetic efficacy data for the second treatment cycle are listed in Table 3 and Fig. 1B. Complete protection from acute vomiting and nausea was attained in 100% and 96.7% of patients, respectively. Complete protection from delayed vomiting and nausea was achieved in 96.7% and 85.2% of patients, respectively. Delayed nausea ratings of none or mild were achieved in 98.3% of patients. Overall, the complete response of vomiting and nausea-free was achieved in 96.7% and 83.6% of patients, respectively [Fig. 1B].

Of the 61 patients who underwent cycles 1 and 2 of chemotherapy, 45 patients (73.8%) experienced neither nausea nor vomiting in either cycle. Four patients (6.5%) refractory to antiemetic effects of agents still had delayed nausea in both cycles. 12 patients (19.7%) experienced episodes of nausea or vomiting in one of the two cycles.

Most primary sites of malignancy in this study are genitourinary and esophageal cancers [Table 1]. The standard doses of cisplatin in genitourinary cancer and esophageal cancer are 50 mg/m2 and 75 mg/m2, respectively. In the first cycle of chemotherapy, 9% of genitourinary cancer patients, and 28% of esophageal cancer patients experienced either nausea or vomiting. In the second cycle of chemotherapy, 8% of genitourinary cancer patients, and 39% of esophageal cancer patients experienced either nausea or vomiting.

The combination of palonosetron, aprepitant, and dexamethasone was generally well-tolerated, with most adverse events mild in intensity. No major adverse events due to antiemetic therapy were recorded. The most commonly reported side effects in the first and the second cycles were constipation (43% and 23%, respectively), hiccup (26% and 18%) and headache (4% and 3%), and there was a decreased incidence of these adverse effects during the second cycle.

Discussion

Cancer patients receiving HEC (e.g., cisplatin ≥50 mg/m2) are at high risk of CINV (>90% frequency of emesis). As a result, antiemetic guidelines recommend the use of a triple combination of 5-HT3RA, NK1RA, and dexamethasone [3], [4]. The second generation 5-HT3RA, palonosetron [10], [11], [12], [21], [22], the NK1RA, aprepitant [15], [16], [23], and the use of dexamethasone [24] have been shown to further enhance the efficacy of antiemetic prophylaxis. Antiemetic prophylaxis should begin in the first cycle of chemotherapy, and should be maintained over subsequent cycles to afford continued protection [3], [4]. In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of a combination of palonosetron, aprepitant, and dexamethasone as primary antiemetic prophylaxis for patients receiving HEC (cisplatin ≥50 mg/m2). The proportion of patients with complete response of vomiting was 100% during the acute interval (day 1), 97% during the delayed interval (days 2–6), and 97% during the overall interval (days 1–6) in the first and second cycles. Complete prevention of nausea and vomiting over both cycles was achieved in 74% of patients. These results confirm that the high efficacy obtained during the first chemotherapy cycle was maintained over the subsequent cycle. Treatment was well tolerated, with no unexpected adverse events. These data showed that palonosetron in combination with aprepitant and dexamethasone is safe and highly effective in preventing CINV in the days following administration of HEC.

Delayed CINV (i.e., CINV occurring or persisting after 24 h postchemotherapy) is particularly common in HEC [25], [26], [27], [28]. According to Warr et al. [29], the triple combination of ondansetron, aprepitant, and dexamethasone proved to be superior over an entire 5-day study period (51% vs. 42%; P = 0.015). However, there was no significant difference during the delayed period (49% vs. 55%; P = 0.064) [29]. We chose long-acting palonosetron because of its superiority over ondansetron in the prevention of emesis and delayed nausea [10], [11], [12], [13]. In our study, most patients experienced no delayed vomiting and more than 85% of patients reported being nausea-free during the delayed phase.

Few trials have assessed the efficacy of the triple combination of palonosetron, aprepitant, and dexamethasone in cancer patients receiving HEC [30], [31], [32]. One trial studying in cancer patients receiving doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide-based or cisplatin-based chemotherapy reported 93% of patients were emesis-free [30]. Longo et al. selected lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapy with cisplatin ≥75 mg/m2 over multiple cycles of chemotherapy [31]. Their results showed complete response rates of 74% and 82% during the first and the last chemotherapy cycles, respectively. In a third trial, gynecological cancer patients receiving chemotherapy with cisplatin ≥50 mg/m2 were investigated [32]. The overall complete response rate for the triple combination was 54.2%. The reduced efficacy in this study may be related to the fact that all the patients were female, and females are known to be more susceptible than males to CINV. In this trial, we studied the patients with different types of cancer, all of whom were undergoing cisplatin-based HEC. Most patients had primary malignancies of the genitourinary system and esophageal cancer. One reason for the better results may be that higher proportion of patients (77%) receiving cisplatin in doses of 50–60 mg/m2. The rest of patients receiving mainly 60–75 mg/m2 of cisplatin may lead to higher rate of delayed nausea, but would not increase the possibility of acute/delayed vomiting or acute nausea after antiemetic protection with the combination of palonosetron, aprepitant, and dexamethasone. In our study, it's hard to make a conclusion of the efficacy of these three anti-emetic agents for patients receiving more than 75 mg/m2 of cisplatin due to insufficient patient numbers with that dose. Furthermore, the parts of patients taking anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, hypnotics, or sedatives may influence the results.

Prior to 2012, aprepitant was reimbursed by the National Health Insurance (NHI) in Taiwan for patients who failed an HEC regimen with 5-HT3RA and dexamethasone antiemetics. Subsequently, the NHI policy was modified to included aprepitant reimbursement for patients in the first and the subsequent cycles of an HEC treatment regimen. One goal of our study was to evaluate the feasibility of this clinical scenario. In a previous study [18], we investigated the efficacy of adding aprepitant as a secondary prophylactic in cases failing to achieve full antiemetic protection with 5-HT3RA and dexamethasone during the first cycle of a cisplatin-based regimen. The results indicated that primary prophylactic use of granisetron plus dexamethasone provided complete protection from cisplatin-induced emesis in 81% of patients. For those in whom primary prophylaxis failed, secondary antiemetic prophylaxis with aprepitant provided complete protection from vomiting in 65% and 77% of patients in the second and third cycles of treatment, respectively. In the present study, aprepitant was included in as a primary prophylactic in a triple antiemetic combination, and nearly all the patients achieved complete protection from vomiting, from the first cycle of chemotherapy. Control of CINV could increase patient adherence to cancer treatment regimens and provide an acceptable quality of life. We suggested that aprepitant-containing primary antiemetic prophylaxis is a feasible and effective means of preventing CINV in patients treated with cisplatin-based HEC.

A limitation of the present study was the relatively small sample size to provide precise and powerful results. Furthermore, the study was not randomized and did not include a control arm. Additional research is needed to further clarify the role of aprepitant in this setting and to determine whether the incremental benefit of triplet therapy with palonosetron and dexamethasone plus aprepitant when compared with palonosetron and dexamethasone alone is worth the additional cost in patients receiving HEC.

Over the last decade, the effectiveness of antiemetic treatment has improved gradually at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taiwan [18], [33]. More than 90% of our patients achieved complete protection from acute nausea and vomiting. The proportion of HEC patients achieving complete protection from delayed nausea and vomiting has improved from approximately 60% and 70% of the patients to 85% and 95%, respectively. The present study investigated the usefulness of palonosetron, in combination with aprepitant and dexamethasone, to prevent both acute and delayed CINV following cisplatin-based HEC. More than 95% of patients experienced no episodes of vomiting and maintained good control of nausea over the 6 days following chemotherapy.

Source of support

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Lindley C., McCune J.S., Thomason T.E., Lauder D., Sauls A., Adkins S. Perception of chemotherapy side effects cancer versus noncancer patients. Cancer Pract. 1999;7:59–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.07205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:865–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roila F., Herrstedt J., Aapro M., Gralla R.J., Einhorn L.H., Ballatori E. Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl. 5):v232–v243. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basch E., Prestrud A.A., Hesketh P.J., Kris M.G., Feyer P.C., Somerfield M.R. Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4189–4198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hesketh P.J. Defining the emetogenicity of cancer chemotherapy regimens: relevance to clinical practice. Oncologist. 1999;4:191–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forni C., Ferrari S., Loro L., Mazzei T., Beghelli C., Biolchini A. Granisetron, tropisetron, and ondansetron in the prevention of acute emesis induced by a combination of cisplatin-Adriamycin and by high-dose ifosfamide delivered in multiple-day continuous infusions. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8:131–133. doi: 10.1007/s005200050027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geling O., Eichler H.G. Should 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonists be administered beyond 24 hours after chemotherapy to prevent delayed emesis? Systematic re-evaluation of clinical evidence and drug cost implications. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1289–1294. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoltz R., Cyong J.C., Shah A., Parisi S. Pharmacokinetic and safety evaluation of palonosetron, a 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonist, in U.S. and Japanese healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:520–531. doi: 10.1177/0091270004264641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong E.H., Clark R., Leung E., Loury D., Bonhaus D.W., Jakeman L. The interaction of RS 25259-197, a potent and selective antagonist, with 5-HT3 receptors, in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114:851–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenberg P., Figueroa-Vadillo J., Zamora R., Charu V., Hajdenberg J., Cartmell A. Improved prevention of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting with palonosetron, a pharmacologically novel 5-HT3 receptor antagonist: results of a phase III, single-dose trial versus dolasetron. Cancer. 2003;98:2473–2482. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gralla R., Lichinitser M., Van Der Vegt S., Sleeboom H., Mezger J., Peschel C. Palonosetron improves prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: results of a double-blind randomized phase III trial comparing single doses of palonosetron with ondansetron. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1570–1577. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubenstein E.B., Gralla R.J., Eisenberg P., Sleeboom O., Vtoraya A., Macciocchi A. Palonosetron (PALO) compared with ondansetron (OND) or dolasetron (DOL) for prevention of acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV). Combined results of two Phase III trials. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;22:729. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubenstein E.B., Macciocchi A. The efficacy of a single fixed 0.25-mg intravenous (IV) dose of palonosetron (PALO) in preventing acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is not affected by body weight. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:373–374. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curran M.P., Robinson D.M. Aprepitant: a review of its use in the prevention of nausea and vomiting. Drugs. 2009;69:1853–1878. doi: 10.2165/11203680-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hesketh P.J., Grunberg S.M., Gralla R.J., Warr D.G., Roila F., de Wit R. The oral neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin – the Aprepitant Protocol 052 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4112–4119. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poli-Bigelli S., Rodrigues-Pereira J., Carides A.D., Julie Ma G., Eldridge K., Hipple A. Addition of the neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist aprepitant to standard antiemetic therapy improves control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Latin America. Cancer. 2003;97:3090–3098. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jordan K., Sippel C., Schmoll H.J. Guidelines for antiemetic treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: past, present, and future recommendations. Oncologist. 2007;12:1143–1150. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-9-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu C.E., Liaw C.C. Using aprepitant as secondary antiemetic prophylaxis for cancer patients with cisplatin-induced emesis. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2357–2361. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1345-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liaw C.C., Chang H.K., Liau C.T., Huang J.S., Lin Y.C., Chen J.S. Reduced maintenance of complete protection from emesis for women during chemotherapy cycles. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26:12–15. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200302000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liaw C.C., Wang C.H., Chang H.K., Wang H.M., Huang J.S., Lin Y.C. Cisplatin-related hiccups: male predominance, induction by dexamethasone, and protection against nausea and vomiting. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aapro M.S., Grunberg S.M., Manikhas G.M., Olivares G., Suarez T., Tjulandin S.A. A phase III, double-blind, randomized trial of palonosetron compared with ondansetron in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1441–1449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito M., Aogi K., Sekine I., Yoshizawa H., Yanagita Y., Sakai H. Palonosetron plus dexamethasone versus granisetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, comparative phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmoll H.J., Aapro M.S., Poli-Bigelli S., Kim H.K., Park K., Jordan K. Comparison of an aprepitant regimen with a multiple-day ondansetron regimen, both with dexamethasone, for antiemetic efficacy in high-dose cisplatin treatment. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1000–1006. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grunberg S.M. Antiemetic activity of corticosteroids in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy: dosing, efficacy, and tolerability analysis. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:233–240. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grunberg S.M., Deuson R.R., Mavros P., Geling O., Hansen M., Cruciani G. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis after modern antiemetics. Cancer. 2004;100:2261–2268. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hickok J.T., Roscoe J.A., Morrow G.R., King D.K., Atkins J.N., Fitch T.R. Nausea and emesis remain significant problems of chemotherapy despite prophylaxis with 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 antiemetics: a University of Rochester James P. Wilmot Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program Study of 360 cancer patients treated in the community. Cancer. 2003;97:2880–2886. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hickok J.T., Roscoe J.A., Morrow G.R., Bole C.W., Zhao H., Hoelzer K.L. 5-Hydroxytryptamine-receptor antagonists versus prochlorperazine for control of delayed nausea caused by doxorubicin: a URCC CCOP randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:765–772. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70325-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dibble S.L., Isreal J., Nussey B., Casey K., Luce J. Delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea in women treated for breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:E40–E47. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.E40-E47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warr D.G., Hesketh P.J., Gralla R.J., Muss H.B., Herrstedt J., Eisenberg P.D. Efficacy and tolerability of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with breast cancer after moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2822–2830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herrington J.D., Jaskiewicz A.D., Song J. Randomized, placebo-controlled, pilot study evaluating aprepitant single dose plus palonosetron and dexamethasone for the prevention of acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer. 2008;112:2080–2087. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longo F., Mansueto G., Lapadula V., Stumbo L., Del Bene G., Adua D. Combination of aprepitant, palonosetron and dexamethasone as antiemetic prophylaxis in lung cancer patients receiving multiple cycles of cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:753–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeshima N., Matoda M., Abe M., Hirashima Y., Kai K., Nasu K. Efficacy and safety of triple therapy with aprepitant, palonosetron, and dexamethasone for preventing nausea and vomiting induced by cisplatin-based chemotherapy for gynecological cancer: KCOG-G1003 phase II trial. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2891–2898. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen P.T., Liaw C.C. Intravenous ondansetron plus intravenous dexamethasone with different ondansetron dosing schedules during multiple cycles of cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Chang Gung Med J. 2008;31:167–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]