Abstract

Background

This study aimed to determine the various bony changes in osteoarthritis (OA) of elderly patients who are suffering from temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD) and to find if all the changes manifesting in generalized OA were presented in temporomandibular joint (TMJ).

Methods

Thirty TMJs of fifteen elderly patients who were diagnosed with TMD were selected for the study. Patient with TMD were subjected to computerized tomographic (CT) imaging, and the various bony changes in the TMJ were recorded.

Results

CT study of TMJ showed that there is a positive evidence of joint involvement in 80% of the cases. In this study, female patients were more commonly affected by OA than the males. The condylar changes (69.93%) are more common than the changes in the articular eminence (6.6%) and condylar fossa (10%). About 56.6% of TMJ in the study was affected by the early manifestations of the OA.

Conclusion

CT study showed that there is a positive evidence of TMJ involvement in the elderly patients with TMD. The results show that condylar changes are more common than the changes in the articular eminence and condylar fossa. The study also shows that most of the patients are affected by early TMJ OA; hence, initiating treatment at early stages may prevent the disease progression.

Keywords: Computed tomography, Temporomandibular joint, Temporomandibular joint dysfunction, Osteoarthritis

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

Osteoarthritis is a degenerative disease affecting the temporomandibular joint. It was observed in the study that more than 80% of the elderly patients with temporomandibular joint dysfunction were more commonly affected by early stage of osteoarthritis.

What this study adds to the field

Advocating early treatment such as topical NSAIDS, occlusal adjustments, jaw self-care, physiotherapy, oral appliance therapy, and intraarticular injection of corticosteroids may help to prevent the disease progression.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is defined as a degenerative condition of the joint characterized by deterioration of articular tissue and concomitant remodeling of underlying subchondral bone [1]. OA is an age-related disease, and the WHO estimates that globally 25% of adults aged over 65 years suffer from pain and disability associated with this disease [2]. The percentage of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) OA in age group 9–90 years range from 28% to 38% and incidence increases with advancing age. The incidence of TMJ OA has received a little attention in past literature and studies are only a few.

OA is caused primarily by the degeneration of collagens and proteoglycans in cartilage leading to fibrillation, erosion, and cracking in the superficial cartilage layer [2]. This process spreads to a deeper layer of cartilage and eventually enlarges to form erosions. The articular surface of TMJ has the remarkable adaptive capacity. Hyaline cartilage of the load-bearing joints of the body are more resistant to compressive loading, but the fibrocartilage of TMJ better withstands shear force [3]. When functional demand exceeds the adaptive capacity of the TMJ or if the affected individual is susceptible to maladaptive response, then the disease state will ensue [3].

The cardinal features of TMJ OA are both clinical and radiographic [4]. The clinical features are tenderness in the joint region, pain on movement of the joint during mouth opening and lateral excursion, and hard grating or crepitus [4], [5]. Radiographic signs of the disease are cortical bone erosion, flattening of joint compartments with productive bone changes such as sclerosis and osteophyte [6]. These signs of TMJ OA represent different stages of the disease process. Erosive lesions and joint space narrowing indicate acute or early change, whereas sclerosis, flattening, subchondral cyst, and osteophyte may indicate late changes in TMJ [7]. This study was done to determine the various bony changes in OA of elderly patients who are suffering from temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD) using computed tomography (CT) and to find if all the changes manifesting in generalized OA were present in TMJ.

Materials and methods

The study group selected consisted of 15 patients out of whom 10 were female and 5 were male from Outpatient Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology. The age range was within 50–80 years with the mean average age of 63.06 years. These patients were examined for TMD. The clinical criteria for TMD were formulated using the standard TMJ questionnaire by Okeson, which includes: (1) tenderness present in the preauricular region, (2) tenderness in the muscles of mastication, (3) limitation or deviation in the mandibular range of motion, and (4) clicking, or popping, or crepitus [8].

The inclusion criteria include patients with age >50 years, generalized OA, TMD at least on one side. The exclusion criteria include the patients who had various problems in the TMJ such as TMJ surgery, direct trauma, fracture of TMJ, myalgia, and congenital craniofacial anomalies. Other than joint problems, patients with pain in the TMJ region due to tooth pain, impacted teeth, ENT surgeries, ear infections, and neuralgias were excluded from the study.

The TMJ pain during mandibular function was evaluated by bilateral manual palpation of the preauricular region and intraauricular region by means of firm pressure. TMJ pain was identified during palpation, mandibular range of motion, or assisted mandibular opening. Tenderness in the muscles of mastication was checked by palpation of each muscle. The mandibular range of motion was evaluated by maximum mouth opening, which was measured from incisal edge of upper central incisor to lower central incisor with a Digital Vernier Caliper or millimeter ruler [9]. The lateral movements were measured relative to the maxillary midline with teeth slightly separated.

On palpation, bilaterally on the lateral side of both TMJ near preauricular region, clicking was elicited [9]. Auscultation was carried out with the diaphragm side of the stethoscope at the preauricular region, with the subject performing three opening and three lateral and protrusive movements [9]. Joint sounds like single or reciprocal click [9] and hard grating or crepitus were evaluated.

The patients satisfying these criteria were subjected to CT scan using multi-slice helical CT. The patient is explained about the entire procedure of the scan and requested to sign the consent form and was advised to remove metal objects such as hair pins and hair clips before the procedure. The patient was taken to the CT scanner (SEIMENS, 125 kV, 500 mA) and placed in supine position on the scanning table with the head placed on the headrest. A small sponge is placed on either side of the head to limit the lateral movements.

The scan was performed with the patient's mouth closed and that the rays were directed parallel to the Frankfort's horizontal plane over a distance of 5 cm at 120 kV and 333 mA, with the scanning table advancing with an increment of 1 mm per rotation [1]. In bone display mode, the scan data were reformed into 0.625 mm interaxial image. The scanning procedure was carried out for 2 min. The axial CT images were taken and reconstructed into sagittal or coronal images, which were obtained by orientation to the long axis of the condyle.

The CT scan images were recorded and interpreted by a qualified radiologist, and the following radiographic changes are defined as.

-

1.

Erosion is an interruption or absence of cortical lining

-

2.

Sclerosis is increased density of cortical lining or the subchondral bone

-

3.

An osteophyte is a marginal bone outgrowth

-

4.

Geodes/subchondral cyst are single or multiple pyriform shape subchondral lesions possessing sclerotic margins of 0.5–2 mm size

-

5.

Joint space narrowing is a reduction in space between the condyle and glenoid fossa in all directions (anterior, superior, and posterior) [10].

As stated by Gynther et al. [11], Hansen et al., have classified joint space narrowing as, reduced – <1.5 mm, normal – between 1.5 and 4 mm, or increased – more than 4 mm. Of five changes stated above even if one change is evident in any one joint, it is considered as TMJ OA [12].

Results

The results of the study showed that out of the 30 joints evaluated, bony changes were presented in 21 (70%) joints [Table 1, Table 2], either in the condyle, glenoid fossa or the articular eminence or a combination. Nine joints showed no changes either in the condyle, glenoid fossa, and articular eminence. Of 30 joints, erosion in condyle was present in 17 joints, joint space narrowing in 12 joints, subchondral cyst or geode of the condyle in four joints, osteophyte in five joints, and sclerosis in five joints were present. One joint showed erosion in the articular eminence, and two joints showed subchondral cyst in the eminence. Two joints showed sclerosis in the condylar fossa, and one joint had subchondral cyst in the condylar fossa.

Table 1.

CT finding of TMJ OA (Case 1–8).

| Joint number | Case no | Age/sex | TMJ | Joint space narrowing | Erosion | Geode | Osteophyte | Sclerosis | Condylar fossa | Articular eminence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Case 1 | 62/female | Right | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2 | Left | + | + | − | + | − | +Cyst | |||

| 3 | Case 2 | 60/female | Right | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 4 | Left | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 5 | Case 3 | 78/female | Right | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 6 | Left | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | ||

| 7 | Case 4 | 50/female | Right | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| 8 | Left | + | + | + | + | + | − | +Erosion +Cyst |

||

| 9 | Case 5 | 69/male | Right | + | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| 10 | Left | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | ||

| 11 | Case 6 | 73/female | Right | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 12 | Left | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 13 | Case 7 | 66/female | Right | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 14 | Left | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 15 | Case 8 | 55/female | Right | + | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| 16 | Left | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

Abbreviations: TMJ: Temporomandibular joint; OA: Osteoarthritis; CT: Computed tomography.

Table 2.

CT finding of TMJ OA (Case 9–15).

| Joint number | Case no | Age/sex | TMJ | Joint space narrowing | Erosion | Geode | Osteophyte | Sclerosis | Condylar fossa | Articular eminence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | Case 9 | 50/female | Right | + | + | − | + | − | +Cyst +Sclerosis |

− |

| 18 | Left | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | ||

| 19 | Case 10 | 80/female | Right | + | − | − | − | + | +Sclerosis | − |

| 20 | Left | + | + | − | − | + | +Sclerosis | − | ||

| 21 | Case 11 | 50/female | Right | − | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 22 | Left | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 23 | Case 12 | 60/female | Right | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 24 | Left | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 25 | Case 13 | 72/male | Right | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 26 | Left | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 27 | Case 14 | 61/male | Right | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 28 | Left | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 29 | Case 15 | 60/male | Right | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 30 | Left | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

Abbreviations: TMJ: Temporomandibular joint; OA: Osteoarthritis; CT: Computed tomography.

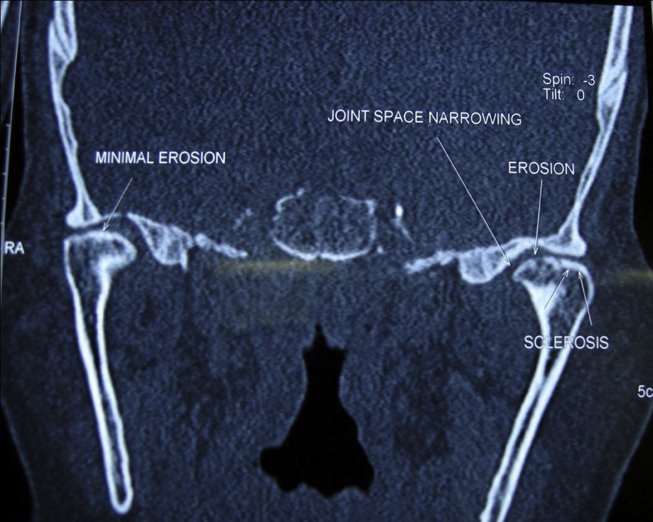

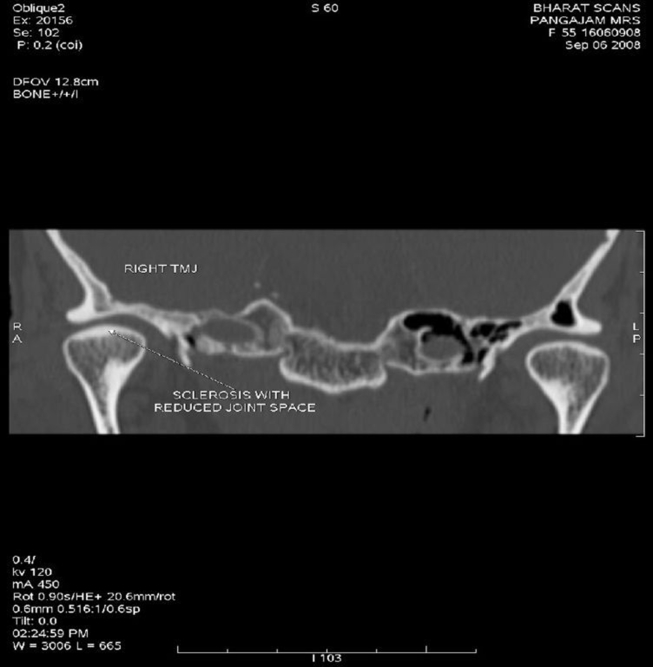

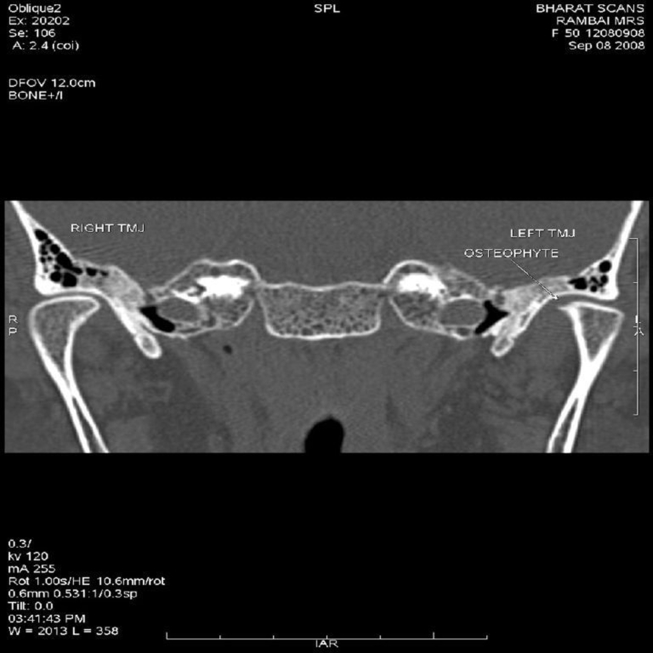

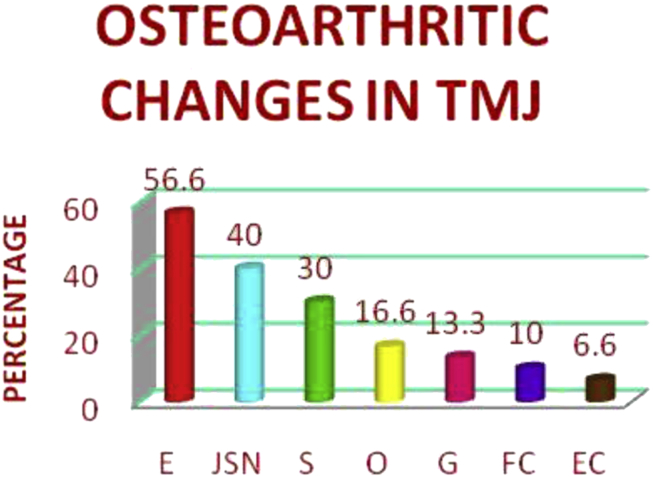

Condylar changes were found to be more predominant than temporal bone changes in the articular eminence and glenoid fossa. Erosion was the predominant finding [Fig. 1] 56.6%, followed in descending order by joint space narrowing 40% [Fig. 1], sclerosis 30% [Fig. 1, Fig. 2], osteophyte 16.6% [Fig. 3, Fig. 4] geode 13.3% [Fig. 5, Fig. 6] changes in the condylar fossa were 10%, and articular eminence 6.6% [Fig. 3]. The percentages of various bony changes were shown in [Fig. 7].

Fig. 1.

Coronal section showing condylar changes in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis.

Fig. 2.

Coronal section showing sclerosis and joint space narrowing.

Fig. 3.

Coronal section showing osteophyte in condyle and cyst in eminence.

Fig. 4.

Coronal section showing osteophyte.

Fig. 5.

Axial section showing Geode (subchondral cyst).

Fig. 6.

Sagittal section showing geode.

Fig. 7.

Percentage of various bony changes in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. E: Erosion; JSN: Joint space narrowing; S: Sclerosis; O: Osteophyte; G: Geode; FC: Fossa changes; EC: Eminence changes.

Discussion

OA has been considered as an age-related degenerative change of the articular cartilage and the subchondral bone in synovial joints including TMJ leading to pain and disability [1]. de Leeuw et al. 1995 stated that of the disorders afflicting the TMJ, OA, and internal derangement are frequently observed [13], [14]. It is stated that progressive nature of internal derangement by several consecutive stage will lead to radiographically visible degenerative changes, which may be extensive [15], [16]. Controversy exists that OA can also lead to disc displacement [7]. This study was carried out to find the various bony changes in TMJ OA in the elderly patients so that initiating treatment at early stages may prevent the disease progression.

Wiberg and Wänman 1998 stated that OA of TMJ seldom occurs in young adults, and it is an age-related disease [7]. All patients included in the study had generalized OA and were in the age range 50–80 years with mean age of 63.06 years. This is in accordance with the American College of Rheumatology criteria for the diagnosis of OA where the age range is described to be above 50 years [17], [18]. OA has a predilection for female sex, and it is more severe in nature involving more number of joints [5], [7]. Low levels of estrogens at the time of menopause have detrimental effect on the intrinsic material property of articular cartilage causing degeneration and erosion. In the present study, out of 15 patients, 10 were female and five were male similar to the earlier studies where the number of females was greater than males [7], [12]. The patient with TMJ OA usually present with TMD such as tenderness in the joint region, pain on movement of the joint during mouth opening, and lateral excursion with a hard grating or crepitus as evident as in our study [4], [5].

Various imaging modalities have been used for assessment of morphological changes in the TMJ [19]. From the early 1980s, CT has been the method of choice for evaluating osseous abnormalities in the TMJ [3], [6], [12], [14], and so used in the present study for evaluation of TMJ OA. Cara et al. stated that CT is an accurate technique and permits visualization of the upper and medial portion of the mandibular condyle and the articular fossa [20]. Despite the highly absorbed dose, CT has greater potential when osseous TMJ abnormalities are of primary concern [6], [15]. Multi-slice helical CT represents a potential advancement in CT that allows obtaining thinner slice and high quality images in less acquisition time [20], [21]. In multi-slice CT, multiple overlapping images can be reconstructed from single examination permitting higher quality reconstructed images without additional patient radiation [20], [21]. Images were obtained in all three planes axial, sagittal, and coronal plains. The sagittal plane is valuable for evaluation of osteophyte, erosion, flattening, and sclerosis [6]. The coronal plane is useful for finding erosion, flattening, and sclerosis; the axial plane for evaluation of erosion and sclerosis [6].

In the present study group, 12 out of 15 patients had OA of TMJ and hence 80% involvement was present which is in accordance to the previous studies [7], [11]. Thirty TMJ were examined for OA changes out of which 21 joints (70%) showed changes in the condyle, glenoid fossa, or articular eminence, or in combination. The study shows that condylar bone changes (69.93%) were greater as compared to the temporal bone changes such as fossa changes (10%), and eminence changes (6.6%) were similar to studies where the condylar bone changes were greater than the temporal bone changes [1], [13]. Erosion (56.6%) and joint space narrowing (40%) were the most predominant finding in this study, which indicates the early changes and osteophyte, sclerosis, and geode were less predominant and represent the advanced stage of the disease. Hence, most of the patients in the study were affected by early manifestation of the disease. Advocating early treatment such as occlusal adjustments, jaw self-care, physiotherapy, oral appliance therapy, topical NSAIDS, and intraarticular injection of corticosteroids may help to prevent the disease progression.

Comparison was made with grades of generalized OA and TMJ OA, but no significant correlation was obtained. Patient with an early stage of generalized OA also present with early lesion of TMJ OA, but in a patient with advanced disease of generalized OA also had an early lesion of TMJ OA. There is an approved grading system for evaluation of generalized OA, which is not present for TMJ OA. This study conducted with a large sample size may yield appropriate results.

Conclusion

CT study showed that there is a positive evidence of TMJ involvement in the elderly patients with TMD. The results show that condylar changes are more common than the changes in the articular eminence and condylar fossa. The study also shows that most of the patients are affected by early TMJ OA; hence, initiating treatment at early stages may prevent the disease progression.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Yamada K., Saito I., Hanada K., Hayashi T. Observation of three cases of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis and mandibular morphology during adolescence using helical CT. J Oral Rehabil. 2004;31:298–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breedveld F.C. Osteoarthritis – the impact of a serious disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43(Suppl. 1):i4–i8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milam S.B. Pathogenesis of degenerative temporomandibular joint arthritides. Odontology. 2005;93:7–15. doi: 10.1007/s10266-005-0056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Sadhan R. The relation between TMJ osteoarthritis and inadequately supported occlusion. Egypt Dent J. 2008;54:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emshoff R., Rudisch A. Validity of clinical diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: clinical versus magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis of temporomandibular joint internal derangement and osteoarthrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91:50–55. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.111129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho B.H., Jung Y.H. Intra and inter-observer agreement of computed tomography in assessment of mandibular condyle. Korean J Oral Maxillofac Radiol. 2007;37:191–195. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiberg B., Wänman A. Signs of osteoarthrosis of the temporomandibular joints in young patients: a clinical and radiographic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:158–164. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okesan J.P. 5th ed. Mosby Publication; 2003. Management of temporomandibular disorders and occlusion. chapter10 pg355–356 and Chapter13 pg465-466. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertram S., Rudisch A., Innerhofer K., Pümpel E., Grubwieser G., Emshoff R. Diagnosing TMJ internal derangement and osteoarthritis with magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:753–761. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks S.L., Brand J.W., Gibbs S.J., Hollender L., Lurie A.G., Omnell K.A. Imaging of the temporomandibular joint: a position paper of the American Academy of oral and maxillofacial radiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:609–618. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gynther G.W., Tronje G., Holmlund A.B. Radiographic changes in the temporomandibular joint in patients with generalized osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:613–618. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiese M., Wenzel A., Hintze H., Petersson A., Knutsson K., Bakke M. Osseous changes and condyle position in TMJ tomograms: impact of RDC/TMD clinical diagnoses on agreement between expected and actual findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:e52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Leeuw R., Boering G., Stegenga B., de Bont L.G. Radiographic signs of temporomandibular joint osteoarthrosis and internal derangement 30 years after nonsurgical treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:382–392. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katzberg R.W. Temporomandibular joint imaging. Radiology. 1989;170:297–307. doi: 10.1148/radiology.170.2.2643133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsiklakis K., Syriopoulos k, Stamatakis H.C. Radiographic examination of the temporomandibular joint using cone beam computed tomography. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2004;33:196–201. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/27403192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurita H., Kojima Y., Nakatsuka A., Koike T., Kobayashi H., Kurashina K. Relationship between temporomandibular joint (TMJ)-related pain and morphological changes of the TMJ condyle in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2004;33:329–333. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/13269559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobson L.T. Definitions of osteoarthritis in the knee and hand. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55:656–658. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.9.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manek N.J., Lane N.E. Osteoarthritis: current concepts in diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:1795–1804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hussain A.M., Packota G., Major P.W., Flores-Mir C. Role of different imaging modalities in assessment of temporomandibular joint erosions and osteophytes: a systematic review. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2008;37:63–71. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/16932758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cara K., Maruhashi L.T., Grauer D., Cevidanes L.S., Styner M.A., Heulfe I. Validity of single and multislice CT for assessment of mandibular condyle lesions. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2007;36:24–27. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/54883281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamada K., Tsuruta A., Hanada K., Hayashi T. Morphology of the articular eminence in temporomandibular joints and condylar bone change. J Oral Rehabil. 2004;31:438–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]