Abstract

Background

The endodontic treatment of teeth with immature root has always been a challenge. To achieve a better prognosis, regenerative endodontic treatment may become a treatment trend for teeth with apical periodontitis and immature roots.

Methods

Clinical and radiographic data were collected from 38 endodontic treated immature teeth (21 apexification and 17 regeneration). Measure the radiographic outcome by quantifying the apical lesion.

Results

There was no statistical difference between the two treatments regarding PAI scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up (p > 0.05). In addition, different operators and the different stages of root development for both techniques showed no significant statistical difference on the final treatment results.

Conclusions

In this study, assessment of the radiographic outcomes indicated that regenerative endodontic treatment were identical to the apexification technique.

Keywords: Regenerative endodontic treatment, Pulp revascularization, Apexification, Periapical index (PAI), Radiology

At a glance commentary

Scientific background of the subject

The conventional treatment of immature teeth with necrotic pulp is apexification which has some inherent disadvantages. A recently regenerative endodontic treatment can help rescue infected immature teeth by promoting continued hard tissue formation and root growth. The regenerative method can become a treatment trend for teeth with pulp necrosis and immature roots.

What this study adds to the field

In the present study, assessment of the radiographic and clinical outcomes indicated that regenerative endodontic treatment was identical to the apexification technique. It offers great potential to substitute the regenerative endodontic treatment for traditional apexification with calcium hydroxide or MTA in immature permanent necrotic teeth.

Numerous reasons exist for early-stage pulp necrosis development in immature permanent teeth. Such reasons include dental caries, trauma, and dental structure abnormalities. Decomposed pulp tissues and bacteria in teeth resulting in pulp necrosis can cause acute to chronic inflamed periapical tissues around the apical foramen; even periapical cysts and osteomyelitis can occur.

Because of the following reasons, substantial challenges are encountered in the treatment of teeth with immature roots [1]:

-

1.

Thin dentin wall: The pulp canal wall is thin, and root fractures easily occur during mechanical debridement.

-

2.

Wide open apex: The apical foramen is not converged, and attaining a favorable apical closure with traditional endodontic treatment is difficult.

-

3.

Challenging behavior: Patients are relatively young when these dental problems occur, and they are nervous, frightened, and impatient during treatment.

The traditional method for treating pulp necrosis in teeth where the root is immature is apexification. This method is used to form hard tissue at the apex to facilitate sealing the root canal. Depending on the type of material used, apexification can be divided into calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) and mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) apexification. Ca(OH)2 apexification has several disadvantages. One disadvantage is that the patient is required to return to the clinic several times for material replacement, and thus the patient must be highly cooperative. Another disadvantage is that long-term placement of Ca(OH)2 may cause the root structure to become fragile [2]. Although MTA apexification is not associated with the aforementioned disadvantages and the treated teeth has a higher survival rate than that treated with Ca(OH)2 apexification [3], neither method can cause the root to continue developing, and the thin canal wall is still subjected to the risk of fracture [4], [5]. Root fractures in teeth with immature roots increase the difficulty of tooth extraction, and considerations must also be made regarding the possibility of an early extraction causing future alveolar bone resorption and the problem of maintaining the space in the dentition.

Teeth with immature roots have an abundant blood supply near the apex, and the surrounding undifferentiated stem cells possess excellent healing potential. The methods for applying apexogenesis to the treatment of pulp necrosis in teeth with immature roots have become increasingly mature over the past decades. Using these regenerative endodontic methods enables the roots to continue regenerating in width and length and even recovers the vitality of pulp [6]. All of the methods mentioned by Hargreaves et al. incorporate the concept of maturogenesis [7].

The objective of this study was to backtrack the two aforementioned treatment methods and compare them after quantifying the apical lesions in teeth with pulp necrosis and the immature roots based on radiographic outcomes. We expected to identify the most effective treatment modality.

Materials and methods

The data were collected from patients who were treated at the dentistry department of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital's northern branch from January 2008 to December 2013. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of CGMH (IRB number: 103-0455B). The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) no systemic diseases, (2) pulp necrosis in premolar caused by dens evaginatus (DE) fracturing, (3) radiographic outcomes showing an immature apex accompanied by apical lesions, and (4) follow-ups at the clinic that continued for more than 1 year. Cases that involved retreatment or traditional endodontic treatments were excluded. The patients' demographic information and relevant clinical tooth treatment data were recorded, and the X-ray images before the treatment and the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month posttreatment follow-ups at the clinic were obtained and interpreted.

The treatment methods were divided into the broad categories of apexification and regeneration. The categorization was performed according to the medical records and radiographic images, and the staffs performing the treatments were categorized as attending physicians or senior resident physicians. All of them are specialized in pediatric dentistry.

The methods used in apexifications are as follows: (1) MTA apexification: After root canal debridement, the working length is confirmed, and the MTA is placed at the apex, at least 3 mm deep, to form an apical seal. Gutta-percha is used to fill the canal, and the crown is then restored with glass ionomer and resin. Completing the treatment requires one or two appointments. (2) Ca(OH)2 apexification: After the debridement step is completed, Ca(OH)2 is placed long-term in the root canal until the apex forms a hard tissue barrier. Subsequently, gutta-percha is used to seal the canal.

The regeneration method comprises three steps: (1) Disinfection of the root canal: Copious 2.5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution is used to thoroughly irrigating the canal. The chemical sterilizing and tissue-dissolving effect of NaOCl is utilized to remove bacteria, and no mechanical debridement or shaping is performed. Ca(OH)2 is placed inside the root canal to the position above coronal half [8], and glass ionomer and resin are subsequently used to form the seal. (2) Create bleeding into canal system: A sterilized #25 K file is used to stab the apex-external tissue to create blood flow, stopping the bleeding at 3 mm below the cemento-enamel junction. (3) Permanent sealing: The coverage of MTA with a depth of 3 mm followed by composite resin filling is applied to obtain a favorable sealing and prevent bacteria from reentering the canal. In this study, if the investigated cases only attained Step 1, they were categorized as Ca(OH)2 regeneration. If Step 2 was implemented, the cases were categorized as pulp revascularizations. Finally, if Step 3 was used to perform a final MTA filling, the cases were categorized as MTA regenerations. All of the samples were included.

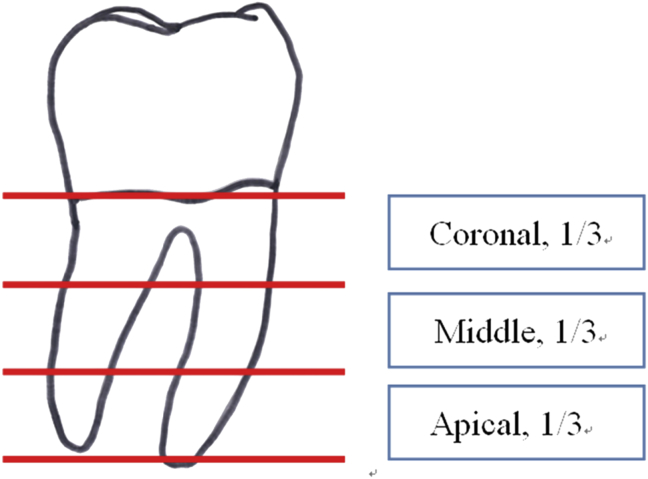

The apical lesions on the radiographic images were quantified and scored according to the periapical index (PAI) [9] which is based on Brynolf's [10] reference radiographs representing various stages of apical periodontitis. Each of the apical status was scored from 1 to 5: the PAI score 1 indicated normal periapical structure; 2, small changes in bone structure; 3, changes in bone structure with some mineral loss; 4, periodontitis with well-defined radiolucent area; 5, severe periodontitis with exacerbating features. The included images that were most similar to the reference images were selected, and their scores were recorded. All PAI scores were measured by the same observer. A re-measurement was conducted 1 week after the first measurement; if any discrepancy occurred, then a second observer performed the assessment and chose the higher score. The categories proposed by Friedman and Mor were modified to interpret the treatment outcomes [Table 1] [11]. In addition, the pretreatment condition of the root development of each test tooth was recorded; the adjacent fully developed first molar was used as a basis for comparing and separating the distance from the cemento-enamel junction to the apex into three equal parts [Fig. 1], thereby enabling the test teeth's apex positions relative to the adjacent first molar to be determined and recorded.

Table 1.

The definition of treatment outcomes [11].

| Outcome | Signs and symptoms | PAI score |

|---|---|---|

| Healed | Non present | PAI score = 1 or 2 |

| Healing | Non present | PAI score = 3 or 4, with score improved at follow-up from immediate post-treatment radiograph |

| Diseased | Present | Score increasing or unchanged at follow-up from immediate post-treatment radiograph |

Fig. 1.

Reference for the stage of root development.

Data were collected, tabulated, and statistically analyzed using statistical analysis software SPSS (Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences 19.0; IBM, Armonk, NY). Fisher's exact test was used for statistical analysis to examine the difference in PAI scores between the treatment methods of each follow-up visit. The effects of different treatments, operators, and stages of root development were also analyzed. A p-value < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

A total of 38 patients met the inclusion criteria; 21 of whom underwent apexification treatment. Of these 21, 3 underwent MTA apexification and 18 underwent Ca(OH)2 apexification. Out of all patients, 17 received regeneration treatment, of which one patient underwent MTA regeneration, two underwent pulp revascularization, and 14 underwent Ca(OH)2 regeneration. Table 2 presents the patients' clinical characteristics and demographic information.

Table 2.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the study population.

| Variable | Treatment method |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apexification (n = 21) |

Regeneration (n = 17) |

||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Sex | Male | 9 | 42.86 | 7 | 41.18 |

| Female | 12 | 57.14 | 10 | 58.82 | |

| Site | Maxilla | 1 | 4.76 | 1 | 5.88 |

| Mandible | 20 | 96.24 | 16 | 94.12 | |

| Abscess | No | 3 | 16.67 | 0 | 0 |

| Yes | 18 | 83.33 | 17 | 100.00 | |

| Cellulitis | No | 15 | 71.43 | 16 | 94.12 |

| Yes | 6 | 28.57 | 1 | 5.88 | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 10.4 ± 1.26 | 10.9 ± 0.98 | |||

| Follow-up time (mo) (mean ± SD) | 24.87 ± 10.67 | 15.73 ± 4.96 | |||

There was no statistical difference between the two treatments regarding PAI scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up (p > 0.05). However, at the 3- and 6-month follow-up, the regeneration treatment showed a tendency to eliminate apical lesions more rapidly than the apexification treatment did (p < 0.1) [Table 3]. Both treatments exhibited considerable success rates, and no statistical difference could be identified between them. Although both techniques corresponded to different operators (attending physicians and resident physicians), the treatment success rate remained high. In addition, the stages of root development of the test teeth showed no significant statistical difference on the final treatment results [Table 4].

Table 3.

Comparison of PAI score between two endodontic techniques at various time points.

| PAI score | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-OP | ||||||

| Apexification (n = 21) | 0 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 10 | 0.910 |

| Regeneration (n = 17) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 9 | |

| Post-OP 1 month | ||||||

| Apexification (n = 12) | 0 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0.603 |

| Regeneration (n = 13) | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| Post-OP 3 month | ||||||

| Apexification (n = 15) | 0 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0.086 |

| Regeneration (n = 12) | 1 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Post-OP 6 month | ||||||

| Apexification (n = 20) | 2 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0.074 |

| Regeneration (n = 12) | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 | |

| Post-OP 12 month | ||||||

| Apexification (n = 20) | 9 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.183 |

| Regeneration (n = 15) | 11 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

Table 4.

The treatment outcome of immature permanent teeth by different categories.

| Categories | Outcome |

Total | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healed | Healing | Diseased | |||

| Type of treatment | |||||

| Apexification, N (%) | 11 (52.38) | 7 (33.33) | 3 (14.29) | 21 | 0.558 |

| Regeneration, N (%) | 12 (70.59) | 4 (23.53) | 1 (5.88) | 17 | |

| Operator | |||||

| Resident physician | 15 (65.22) | 7 (30.43) | 1 (4.35) | 23 | 0.379 |

| Attending physician | 8 (53.33) | 4 (26.67) | 3 (20.00) | 15 | |

| Root development level | |||||

| Middle, 1/3 | 8 (61.54) | 2 (15.38) | 3 (23.08) | 13 | 0.167 |

| Apical, 1/3 | 17 (68.00) | 7 (8.00) | 1 (4.00) | 25 | |

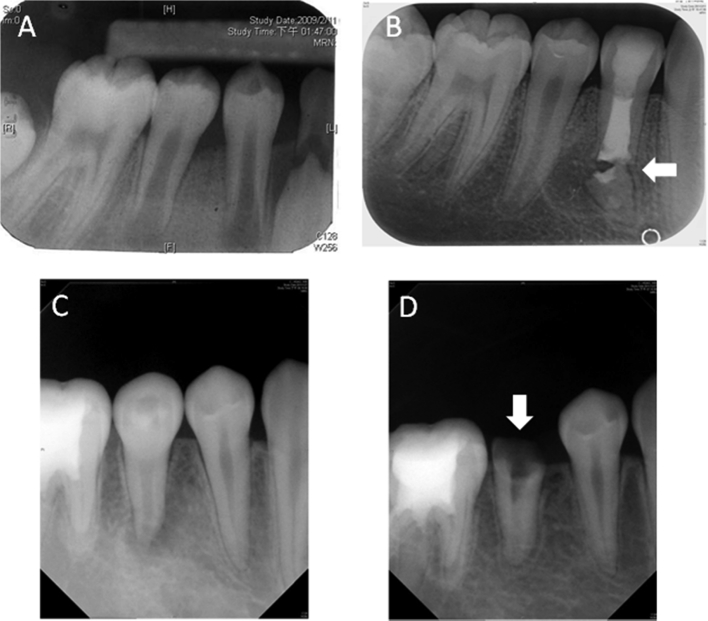

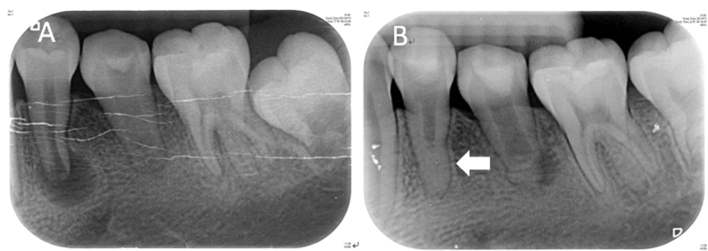

The primary complication of apexification was tooth fracture (14.3%). Among three cases, two exhibited cervical fractures and one exhibited apical fracture [Fig. 2]. The average time of complication occurrence was 1.7 years post-operation. No tooth fractures occurred among the patients who underwent regeneration treatment; however, pulp canal obliteration occurred in the regenerated root tissues [Fig. 3]. Of the 17 regeneration cases, three exhibited pulp canal obliteration, accounting for 17.6% of the cases.

Fig. 2.

Treatment complication of apexification. Case 1. Ten-year-old boy, the diagnosis of #44: Pulp necrosis and chronic apical abscess; presence of apical fistula. (A) Pre-op radiograph. (B) The one year and 3 months follow-up of a case treated with Ca(OH)2 apexification showed apical fracture. Case 2. Ten-year-old girl, the diagnosis of #45: Pulp necrosis and chronic apical abscess. (C) Pre-op radiograph. (D) The one year follow-up of a case treated with Ca(OH)2 apexification showed cervical fracture.

Fig. 3.

Treatment complication of regeneration. Ten-year-old girl, the diagnosis of #34 and #35: Pulp necrosis and chronic apical periodontitis. (A) #34 Pre-op radiograph; #35 has been under Ca(OH)2 apexification for 4 month, showing apical hard barrier formation. (B) The two year and 3 months follow-up of #34 treated with pulp revascularization showed complete maturation of root apex and pulp canal obliteration in apical third portion of root. Two year and 7 months after initial treatment of #35, radiolucent lesion presented at distal aspect of root.

Discussion

Only patients with DE fracture of premolars were sampled in this study because the reasons for pulp necrosis caused by pulp exposure after DE fracture or attrition are unsophisticated than those caused by caries or dental trauma which fewer variables can influence the prognosis. This criterion set the present study apart from most studies on similar topics, which generally include dental caries and trauma in their samples. The incidence of DE among Asians is approximately 2% [12], which is higher than among other ethnicities. Among these 2%, the incidence is higher among females than among males, and correspondent with our study (57.9%). The occurrence of DE fracture was concentrated on the mandible, presumably because DE frequently occurs on the lingual side of the buccal cusp which is part of the functional cusp, and thus fracture or attrition can occur relatively easily when the occlusal force is exercised [13]. The symptoms typically appear at approximately 10 years old, which is about 6 months after the tooth eruption of the mandibular premolars. Therefore, using X-rays to discover DE at an early stage and conducting preventive treatment is crucial.

Teeth with open apex demonstrate greater regeneration potential because the abundant blood supply can facilitate retention and induction of stem cells with differentiation ability [7], [14]. Most of the literature suggested that intracanal-bleeding induction step was critical in the pulp regeneration. However, whether using instruments to deliberately damage the periapical tissue and cause bleeding also harms the Hertwig's root sheath cells required for root growth and hinders the possibility of regeneration still warrants discussion [15]. In this study, 15 of the 17 regeneration patients did not undergo this step, and their results were still successful. This result is consistent with Chueh et al. [16]; apical lesions can still be completely eliminated without the intracanal-bleeding induction step, and the root can still grow. Therefore, experiments should be conducted to verify whether this step is necessary.

The PAI is a precise measurement method that possesses repeatability and is frequently used to assess the results of root canal treatment in permanent teeth [17]. Regarding the results of root canal treatment in teeth with pulp necrosis and immature roots, previous studies have frequently only described whether the apical lesions decreased, unchanged, increased, or disappeared. PAI score is featured in this study for quantifying the apical lesions precisely [18], [19]. The radiographic outcomes indicated no significant differences in the final treatment results according to treatment modality, operator, or root developmental stage. However, the operational steps involved in the regeneration method are simpler than those in conventional apexification; thus, the clinical treatment time can be shortened, which is a great advantage for treating children with behavioral difficulties. In addition, no significant differences in treatment results were found regarding operator (resident physician or attending physician), indicating that the regeneration method is easy to perform.

Regarding the occurrence of post-operative pulp canal obliteration, previous research has attributed this phenomenon to odontoblast-like cell activation, with possible reasons including trauma, tooth fracture, tooth replantation, pulp necrosis, and periodontal disease [20]. However, the reasons for pulp canal obliteration after regenerative procedures remain unknown; studies have indicated that it could be because of internal replacement resorption during the hard tissue regeneration inside the root canal [6]. Whether this influences dental treatment results has currently not been decided, and a longer follow-up period would be required to observe the results.

The limitation of the present study is the small sample size due to the low prevalence of DE. We expect that a larger sample size would support the results of this study. The importance of periodic return to the clinic must be emphasized when treating this type of patients in the future. In addition, changes in root growth and pulp activity should be discussed in more depth.

Conclusion

Thoroughly removing the infection source in the root canal not only eliminates apical lesions in teeth with pulp necrosis and immature roots but also increases the possibility of the regeneration of the pulp–dentin composition. In addition, the assessment of the radiographic outcomes indicated that the results of the regeneration treatment were identical to those of the conventional apexification treatment. Thus, regenerative endodontic treatment can become a treatment trend for teeth with pulp necrosis and immature roots. Future studies with larger sample size are needed to confirm the results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Thibodeau B., Trope M. Pulp revascularization of a necrotic infected immature permanent tooth: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dent. 2007;29:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreasen J.O., Farik B., Munksgaard E.C. Long-term calcium hydroxide as a root canal dressing may increase risk of root fracture. Dent Traumatol. 2002;18:134–137. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2002.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeeruphan T., Jantarat J., Yanpiset K., Suwannapan L., Khewsawai P., Hargreaves K.M. Mahidol study 1: comparison of radiographic and survival outcomes of immature teeth treated with either regenerative endodontic or apexification methods—a retrospective study. J Endod. 2012;38:1330–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwaya S.I., Ikawa M., Kubota M. Revascularization of an immature permanent tooth with apical periodontitis and sinus tract. Dent Traumatol. 2001;17:185–187. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2001.017004185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banchs F., Trope M. Revascularization of immature permanent teeth with apical periodontitis: new treatment protocol? J Endod. 2004;30:196–200. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y.H., Chen K.L., Chen C.A., Tayebaty F., Roseberg P.A., Lin L.M. Responses of immature permanent teeth with infected necrotic pulp tissue and apical periodontitis/abscess to revascularization procedures. Int Endod J. 2012;24:294–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hargreaves K.M., Giesler T., Henry M., Wang Y. Regeneration potential of the young permanent tooth: what does the future hold? J Endod. 2008;34:S51–S56. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diogenes A., Henry M.A., Teixeira F.B., Hargreaves K.M. An update on clinical regenerative endodontics. Endod Top. 2013;28:2–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ørstavik D., Kerekes K., Eriksen H.M. The periapical index: a scoring system for radiographic assessment of apical periodontitis. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1986;2:20–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1986.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brynolf I. A histological and roentgenological study of the periapical region of human upper incisors. Odontol Revy. 1967;18(Suppl. 11):1–176. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman S., Mor C. The success of endodontic therapy: healing and functionality. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2004;32:493–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen R.S. Conservative management of dens evaginatus. J Endod. 1984;10:253–257. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(84)80058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ju Y. Dens evaginatus: a difficult diagnostic problem. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1991;15:314–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chueh L.H., Huang G.T. Immature teeth with periradicular periodontitis or abscess undergoing apexogenesis: a paradigm shift. J Endod. 2006;32:1205–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonoyama W., Liu Y., Yamaza T., Tuan R.S., Wang S., Shi S. Characterization of the apical papilla and its residing stem cells from human immature permanent teeth: a pilot study. J Endod. 2008;34:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chueh L.H., Ho Y.C., Kuo T.C., Lai W.H., Chen Y.H., Chiang C.P. Regenerative endodontic treatment for necrotic immature permanent teeth. J Endod. 2009;35:160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarcin B., Gumru B., Iriboz E., Turkaydin D.E., Ovecoglu H.S. Radiologic assessment of periapical health: comparison of 3 different index systems. J Endod. 2015;41:1834–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holden D.T., Schwartz S.A., Kirkpatrick T.C., Schindler W.G. Clinical outcomes of artificial root-end barriers with mineral trioxide aggregate in teeth with immature apices. J Endod. 2008;34:812–817. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pace R., Giuliani V., Nieri M., Di Nasso L., Pagavino G. Mineral trioxide aggregate as apical plug in teeth with necrotic pulp and immature apices: a 10-year case series. J Endod. 2014;40:1250–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cvek M. Endodontic management and the use of calcium hydroxide in traumatized permanent teeth. In: Andreasen J.O., Andreasen F.M., Andersson L., editors. Textbook and color atlas of traumatic injuries to the teeth. 4th ed. Blackwell; Oxford: 1994. pp. 598–657. [Google Scholar]