Abstract

Background

The Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS) is a nation-wide birth cohort study investigating environmental effects on children’s health and development. In this study, the exposure characteristics of the JECS participating mothers were summarized using two questionnaires administered during pregnancy.

Methods

Women were recruited during the early period of their pregnancy. We intended to administer the questionnaire during the first trimester (MT1) and the second/third trimester (MT2). The total number of registered pregnancies was 103,099.

Results

The response rates of the MT1 and MT2 questionnaires were 96.8% and 95.1%, respectively. The mean gestational ages (SDs) at the time of the MT1 and MT2 questionnaire responses were 16.4 (8.0) and 27.9 (6.5) weeks, respectively. The frequency of participants who reported “lifting something weighing more than 20 kg” during pregnancy was 5.3% for MT1 and 3.9% for MT2. The Cohen kappa scores ranged from 0.07 to 0.54 (median 0.31) about the occupational chemical use between MT1 and MT2 questionnaires. Most of the participants (80%) lived in either wooden detached houses or steel-frame collective housing. More than half of the questionnaire respondents answered that they had “mold growing somewhere in the house”. Insect repellents and insecticides were used widely in households: about 60% used “moth repellent for clothes in the closet,” whereas 32% applied “spray insecticide indoors” or “mosquito coil or an electric mosquito repellent mat.”

Conclusions

We summarized the exposure characteristics of the JECS participants using two maternal questionnaires during pregnancy.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12199-018-0733-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Birth cohort, Epidemiology, Exposure, Japan Environment and Children’s Study, JECS

Background

The Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS) is a nation-wide birth cohort study initiated in 2011. JECS aims to investigate relationships between environmental factors and children’s health and development by recruiting 100,000 expectant mothers [1–3]. In JECS, children are followed from before birth to 13 years old. The exposures during the prenatal period were assessed using self-administered questionnaires and biological samples collected from the mothers during the first trimester, during the second/third trimester, and after delivery. Postnatal exposures were assessed mainly using questionnaires administered to the mothers every 6 months after birth [1].

Exposure assessment during the prenatal and postnatal period in a birth cohort study is critical to investigate the effect of the environment on children’s health because their developing organs are susceptible to various environmental factors [4]. Many birth cohort studies have been conducted aiming to illustrate the environmental effects on children’s health, including the Danish National Birth Cohort [5], the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) [6, 7], Generation R in the Netherlands [8] and the Mothers’ and Children’s Environmental Health study in South Korea [9]. In JECS, the exposure assessment is based on four approaches: (1) questionnaires, (2) biomonitoring, (3) environmental measurements, and (4) simulation models [2, 3]. The current leading risk factors for the global disease burden are high blood pressure, tobacco smoking including second-hand smoke, household air pollution, and diet. Moreover, worldwide, the contribution of different risk factors to the disease burden has changed substantially, with a shift away from the risks of communicable diseases in children toward those of non-communicable diseases in adults [10]. At the same time, the causation of many chronic diseases and developmental disorders is poorly understood still. For example, the development and exacerbation of asthma can be associated with the complex interactions between environmental, social, and lifestyle factors (e.g., ambient air quality, house dust, mold, and smoking) as well as genetic and epigenetic factors [11]. Therefore, we should assess as many environmental exposures as possible in a birth cohort study instead of using a “one-exposure-one-health-effect” approach [12]. Not all exposures can be measured by biomonitoring or environmental monitoring. For some exposures, e.g., occupational history, daily consumer products, and dwelling condition, we had to rely on questionnaire for data collection. Since we had not found any standardized exposure questionnaire, we developed our own questionnaire for the use in JECS. Thus, it is important for us to characterize JECS exposure questionnaire data for the later use in the analysis of the association between environmental factors and children’s health. To our knowledge, this is the first to compare the responses of approximately 100,000 pregnant women to the exposure questionnaires administered twice during early and mid–late pregnancy periods. In this paper, we describe the environmental exposures of the JECS participants using two maternal questionnaires during pregnancy. We assessed whether pregnant women changed the environmental, lifestyle, and/or workload during pregnancy. The questionnaires were designed to collect information associated with chemical exposures such as dwelling conditions, indoor environment, usage of consumer products, and occupation.

Methods

Study protocol

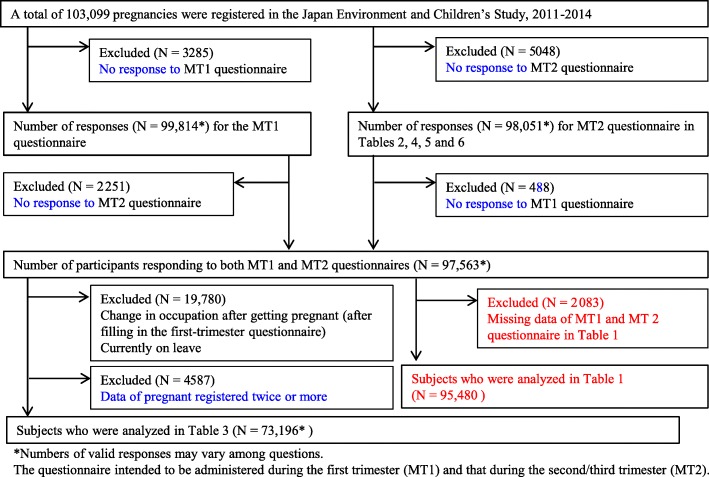

The JECS study protocol has been published elsewhere [1]. Briefly, 15 Regional Centers were selected to cover wide geographical areas in Japan, located from the north, Hokkaido, to the south, Okinawa [1]. The recruitment took place from January 2011 to March 2014. The eligibility criteria for participants (expecting mothers) were as follows: (1) They should reside in the study areas at the time of the recruitment and are expected to reside continually in Japan for the foreseeable future, (2) expected delivery date should be between 1 August 2011 and mid-2014, and (3) they should be capable to participate in the study without difficulty, i.e., must be able to comprehend the Japanese language and complete the self-administered questionnaire [1]. Self-administered questionnaires completed by the mothers during the first trimester and the second/third trimester were used to collect information on demographic factors, medical and obstetric history, physical and mental health, lifestyle, occupation, environmental exposure at home and in the workplace, housing conditions, and socioeconomic status. The baseline characteristics of the participants have been described elsewhere [2]. In this paper, we report the information about the use of chemical substances by mothers and their work/home environments using questionnaires administered during their pregnancy. We summarized two maternal questionnaires, i.e., the questionnaire intended to be administered during the first trimester (MT1) and that during the second/third trimester (MT2). The MT1 questionnaire collected information on activities and chemical use related to occupation during their pregnancy as exposure metrics. The MT2 questionnaire repeated the questions asked in the MT1 questionnaire and then collected data on their dwelling conditions, the indoor environment, and the use of consumer products (see Supplemental methods). The numbers of responses from the JECS participants for the MT1 and MT2 questionnaires are provided in Fig. 1. The total number of registered pregnancies was 103,099. The response rates of the MT1 and MT2 questionnaire were 96.8% and 95.1%, respectively. The mean gestational ages (SD) at the time of the MT1 and MT2 questionnaire responses were 16.4 (8.0) and 27.9 (6.5) weeks, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Environmental exposure data from questionnaires administered to first-trimester and second/third-trimester pregnant women in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS)

Statistical analysis

The present study was based on the data set jecs-ag-20160424. Categorical variables were reported as a median with interquartile ranges, and categorical variables were the proportion of each questionnaire item to the total number of response. All analyses were performed using JMP version 12.2.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and P value < 0.0001 was considered statistically significant. We used the McNemar test to assess the differences in proportions between MT1 and MT2. The two questionnaires agreement was assessed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (kappa scores) [13]. The kappa score of 0–0.20 was characterized as poor agreement or no agreement beyond chance, 0.21–0.40 as fair, 0.41–0.60 as moderate, 0.61–0.80 as substantial, and 0.81–1.00 as almost perfect agreement [14].

Results

The total number of pregnant women participating in JECS was 103,099. Michikawa et al. [2] have published previously the baseline characteristics of the JECS participants, including age at delivery, marital status, family composition, educational background, household income, and passive smoking (presence of smokers at home). The mean gestational ages (SD) at the time of the MT1 and MT2 questionnaire responses were 16.4 (8.0) and 27.9 (6.5) weeks, respectively.

Table 1 shows the workload characteristics during work and daily life at the current time and at any time since becoming pregnant. The numbers of participants who reported workloads of “lifting something weighing more than 20 kg” and “going in and out of commercial refrigerator or freezer” decreased significantly from the first trimester to the second/third trimester. In contrast, workloads of “exposed to loud noise” and “using manufacturing tools with vibration” increased significantly.

Table 1.

Characteristics of workload from workplace, hobbies, and household during pregnancy as reported via two questionnaires of the MT1 and MT2 in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS)

| Variables | MT1 | MT2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| I have been engaged in at least one of the following activities from nos. 1 to 7 after becoming pregnant | |||||

| Yes | 13,410 | 14.0 | 11,306 | 11.8 | < 0.0001 |

| No | 82,070 | 86.0 | 84,174 | 88.2 | |

| 1. Lifting objects that weigh more than 20 kg | |||||

| Yes | 5078 | 5.3 | 3744 | 3.9 | < 0.0001 |

| No | 90,402 | 94.7 | 91,736 | 96.1 | |

| 2. Exposed to loud noise | |||||

| Yes | 3353 | 3.5 | 3597 | 3.8 | < 0.0001 |

| No | 92,127 | 96.5 | 91,883 | 96.2 | |

| 3. Going in and out of commercial refrigerator or freezer | |||||

| Yes | 2646 | 2.8 | 2091 | 2.2 | < 0.0001 |

| No | 92,834 | 97.2 | 93,389 | 97.8 | |

| 4. Working in a hot place that makes one sweat | |||||

| Yes | 1841 | 1.9 | 1719 | 1.8 | 0.0078 |

| No | 93,639 | 98.1 | 93,761 | 98.2 | |

| 5. Using organic solvent | |||||

| Yes | 1508 | 1.6 | 1583 | 1.7 | 0.0288 |

| No | 93,972 | 98.4 | 93,897 | 98.3 | |

| 6. Handling powder dust | |||||

| Yes | 810 | 0.8 | 850 | 0.9 | 0.1211 |

| No | 94,670 | 99.2 | 94,630 | 99.1 | |

| 7. Using manufacturing tools with vibration | |||||

| Yes | 417 | 0.4 | 565 | 0.6 | < 0.0001 |

| No | 95,063 | 99.6 | 94,915 | 99.4 | |

P values are by McNemar test. The questionnaire intended to be administered during the first trimester (MT1) and that during the second/third trimester (MT2)

N number of valid responses

Table 2 shows the frequencies of workload characteristics after becoming pregnant as reported in MT2. The frequency of “lifting something weighing more than 10 kg (including a child),” “using a tool/equipment or riding a vehicle with a strong vibration,” “going in and out of a commercial refrigerator or freezer,” and “working in a hot place that makes one sweaty” more than once a month were 67%, 1.6%, 4.5%, and 0.3%, respectively.

Table 2.

Workload characteristics after becoming pregnant as reported via second/third trimester (MT2) questionnaire in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS)

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of lifting something weighing more than 10 kg (including a child) after becoming pregnant | 97,587 | |

| Never | 32,133 | 32.9 |

| 1–3 times a month | 17,251 | 17.7 |

| 1–4 times a week | 15,582 | 16.0 |

| 5 times a week or more | 32,621 | 33.4 |

| Living or working in a noisy environment after becoming pregnant | 97,502 | |

| No | 87,260 | 89.5 |

| Yes | 10,242 | 10.5 |

| Frequency of working sometime between 10 p.m. and dawn after becoming pregnant | 97,491 | |

| Never | 89,394 | 91.7 |

| 1–3 times a month | 4614 | 4.7 |

| 1–4 times a week | 3002 | 3.1 |

| 5 times a week or more | 481 | 0.5 |

| Frequency of working in a hot place that makes one sweaty after becoming pregnant | 97,472 | |

| Never | 89,385 | 91.7 |

| 1–3 times a month | 3979 | 4.1 |

| 1–4 times a week | 3059 | 3.1 |

| 5 times a week or more | 1049 | 1.1 |

| Frequency of going in and out of a commercial refrigerator or freezer after becoming pregnant | 97,396 | |

| Never | 93,039 | 95.5 |

| 1–3 times a month | 1506 | 1.6 |

| 1–4 times a week | 1967 | 2.0 |

| 5 times a week or more | 884 | 0.9 |

| Frequency of using a tool/equipment or riding a vehicle with a strong vibration after becoming pregnant | 97,453 | |

| Never | 95,911 | 98.4 |

| 1–3 times a month | 939 | 1.0 |

| 1–4 times a week | 383 | 0.4 |

| 5 times a week or more | 220 | 0.2 |

N number of valid responses, MT2 questionnaire administered to second/third-trimester pregnant women

Table 3 summarizes the occupational use of chemicals after becoming pregnant. Using a questionnaire similar to those used in MT1 and MT2 (for details see Additional file 1), Cohen’s kappa scores ranged from 0.07 to 0.54 (median 0.31). The kappa scores demonstrated mostly fair (between 0.21 and 0.4) to moderate (between 0.41 and 0.6) agreement between MT1 and MT2 except for the use of mercury and engine oil (poor, kappa scores up to 0.2).

Table 3.

Frequency of the occupational use of chemicals for more than half a day during pregnancy (MT1 and MT2 questionnaires)

| MT1 | MT2 | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | Kappa scores | |

| Anti-cancer drug (not including your own remedy) | N = 63,576 | ||

| No | 98.7 | 98.8 | 0.54 |

| 1–3 times a month | 0.8 | 0.9 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| Everyday | < 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Lead-free solder | N = 63,388 | ||

| No | 99.7 | 99.7 | 0.54 |

| 1–3 times a month | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| Everyday | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Any products containing lead like solder | N = 63,388 | ||

| No | 99.7 | 99.7 | 0.45 |

| 1–3 times a month | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Everyday | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Formalin, formaldehyde | N = 63,584 | ||

| No | 99.2 | 99.2 | 0.44 |

| 1–3 times a month | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| Everyday | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Microbes | N = 63,399 | ||

| No | 99.6 | 99.6 | 0.44 |

| 1–3 times a month | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| Everyday | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| General anesthetic for surgery at hospital | N = 63,611 | ||

| No | 99.2 | 99.1 | 0.42 |

| 1–3 times a month | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Everyday | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Photo copying machine, laser printer | N = 64,895 | ||

| No | 70.6 | 66.1 | 0.39 |

| 1–3 times a month | 8.1 | 11.4 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 14.2 | 15.2 | |

| Everyday | 7.1 | 7.3 | |

| Radiation, radioactive substances, isotopes | N = 63,385 | ||

| No | 98.1 | 98.5 | 0.38 |

| 1–3 times a month | 0.9 | 0.7 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 0.8 | 0.5 | |

| Everyday | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| Medical sterilizing disinfectant | N = 63,931 | ||

| No | 88.5 | 86.8 | 0.37 |

| 1–3 times a month | 3.3 | 5.3 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 6.0 | 5.8 | |

| Everyday | 2.3 | 2.0 | |

| Dyestuffs (hair coloring) | N = 62,560 | ||

| No | 93.4 | 90.8 | 0.32 |

| 1–3 times a month | 5.5 | 8.0 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 0.6 | 0.7 | |

| Everyday | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| Permanent marker | N = 64,471 | ||

| No | 70.3 | 60.5 | 0.30 |

| 1–3 times a month | 15.8 | 23.6 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 11.1 | 13.2 | |

| Everyday | 2.8 | 2.7 | |

| Paint | N = 63,569 | ||

| No | 80.0 | 72.9 | 0.29 |

| 1–3 times a month | 10.2 | 15.5 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 7.8 | 9.1 | |

| Everyday | 2.4 | 2.5 | |

| Chromium, arsenic, cadmium | N = 63,386 | ||

| No | 99.9 | 99.9 | 0.28 |

| 1–3 times a month | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | |

| 1–6 times a week | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | |

| Everyday | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | |

| Organic solvents | N = 63,471 | ||

| No | 92.9 | 91.1 | 0.27 |

| 1–3 times a month | 5.4 | 7.2 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 1.4 | 1.4 | |

| Everyday | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Chlorine bleach, germicide | N = 64,016 | ||

| No | 81.1 | 73.7 | 0.27 |

| 1–3 times a month | 13.2 | 19.7 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 4.9 | 5.8 | |

| Everyday | 0.8 | 0.8 | |

| Kerosene, petroleum, benzene, gasoline | N = 63,778 | ||

| No | 90.2 | 84.2 | 0.26 |

| 1–3 times a month | 7.7 | 12.5 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 2.0 | 3.2 | |

| Everyday | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Insecticide | N = 63646 | ||

| No | 94.3 | 91.9 | 0.21 |

| 1–3 times a month | 4.8 | 7.0 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 0.9 | 1.0 | |

| Everyday | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Herbicide | N = 62837 | ||

| No | 99.4 | 98.9 | 0.19 |

| 1–3 times a month | 0.6 | 1.1 | |

| 1–6 times a week | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | |

| Everyday | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | |

| Engine oil | N = 63519 | ||

| No | 99.0 | 99.2 | 0.18 |

| 1–3 times a month | 0.7 | 0.6 | |

| 1–6 times a week | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Everyday | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Mercury | N = 63,288 | ||

| No | 99.7 | 99.4 | 0.07 |

| 1–3 times a month | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| 1–6 times a week | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | |

| Everyday | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | |

| Agricultural chemical not listed above or unidentified | N = 64,388 | ||

| No | 99.8 | No data | |

| 1–3 times a month | 0.1 | ||

| 1– 6 times a week | < 0.1 | ||

| Everyday | < 0.1 | ||

| Other chemical substances | N = 64,313 | ||

| No | 99.1 | No data | |

| 1–3 times a month | 0.2 | ||

| 1–6 times a week | 0.4 | ||

| Everyday | 0.3 | ||

The questionnaire intended to be administered during the first trimester (MT1) and that during the second/third trimester (MT2)

N number of valid responses

Table 4 presents the dietary habits during pregnancy as reported on the MT2 questionnaire. Frequency of eating “fast foods,” “retort pouch foods,” “instant noodles, soups, or other foods packed in plastic cups that can be cooked by pouring hot water,” and “canned foods” more than once a week were 15%, 23%, 21%, and 7%, respectively. Frequency of “eating pre-packed foods sold at convenience stores, supermarkets or box lunch shops,” “eating out at a restaurant or eating place,” and “eating frozen foods” more than once a week were 38%, 46%, and 33%, respectively.

Table 4.

Dietary habits during pregnancy for breakfast, lunch, or dinner during the last month (MT2)

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Eating out at a restaurant or eating place | 97,528 | |

| Less than once a week | 52,962 | 54.3 |

| 1–2 times a week | 40,545 | 41.6 |

| 3–4 times a week | 3261 | 3.3 |

| 5–6 times a week | 601 | 0.6 |

| Everyday | 159 | 0.2 |

| Eating pre-packed foods sold at convenience stores, supermarkets or box lunch shops | 97,505 | |

| Less than once a week | 60,850 | 62.4 |

| 1–2 times a week | 27,797 | 28.5 |

| 3–4 times a week | 6485 | 6.7 |

| 5–6 times a week | 1798 | 1.8 |

| Everyday | 575 | 0.6 |

| Eating frozen foods | 97,381 | |

| Less than once a week | 65,068 | 66.8 |

| 1–2 times a week | 22,767 | 23.4 |

| 3–4 times a week | 7313 | 7.5 |

| 5–6 times a week | 1663 | 1.7 |

| Everyday | 570 | 0.6 |

| Eating retort pouch foods | 97,284 | |

| Less than once a week | 75,387 | 77.5 |

| 1–2 times a week | 20,012 | 20.6 |

| 3–4 times a week | 1668 | 1.7 |

| 5–6 times a week | 170 | 0.2 |

| Everyday | 47 | < 0.1 |

| Eating instant noodles, soups, or other foods packed in plastic cups that can be cooked by pouring hot water | 97,277 | |

| Less than once a week | 77,380 | 79.5 |

| 1–2 times a week | 17,758 | 18.3 |

| 3–4 times a week | 1869 | 1.9 |

| 5–6 times a week | 213 | 0.2 |

| Everyday | 57 | 0.1 |

| Fast-food intake (e.g., French fries, pizza, donuts) | 97,367 | |

| Less than once a week | 82,699 | 84.9 |

| 1–2 times a week | 13,845 | 14.2 |

| 3–4 times a week | 736 | 0.8 |

| 5–6 times a week | 71 | 0.1 |

| Everyday | 16 | < 0.1 |

| Eating canned foods | 96,915 | |

| Less than once a week | 89,919 | 92.8 |

| 1–2 times a week | 6662 | 6.9 |

| 3–4 times a week | 288 | 0.3 |

| 5–6 times a week | 32 | < 0.1 |

| Everyday | 14 | < 0.1 |

N Number of valid responses

Table 5 presents the household environment characteristics such as dwelling condition, air conditioning, cleanup, and mobile phone use during pregnancy collected via the MT2 questionnaire. Most of the participants (80%) lived in either wooden detached houses or steel-frame collective housing. The proportion of the respondents living in a housing that was over 20 years old was 35%. More than half of the questionnaire respondents answered that they had “mold growing somewhere in the house,” with the bathroom being the most frequent site of mold. Wooden floors (covered by carpets, tiles, or no covering) were present in 78% of the residences. As for household cleaning, 92% of the participants had been vacuuming more than once a week. The proportion of participants who did not have a mobile phone was 0.1–0.2%.

Table 5.

Household environment characteristics during pregnancy (MT2)

| Category | Variables | N | Median | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (25th–75th percentiles) | ||||

| Dwelling condition and material | Type of residence | 97,315 | ||

| Wooden detached house | 40,269 | 41.4 | ||

| Steel-frame detached house | 6190 | 6.4 | ||

| Wooden multiple-dwelling house/apartment | 12,042 | 12.4 | ||

| Steel-frame multiple-dwelling house/apartment | 37,861 | 38.9 | ||

| Others | 953 | 1.0 | ||

| Age of house/apartment building | 97,238 | |||

| < 1 year | 5432 | 5.6 | ||

| 1 ≦ year < 3 | 10,920 | 11.2 | ||

| 3 ≦ year < 5 | 9152 | 9.4 | ||

| 5 ≦ year < 10 | 14,903 | 15.3 | ||

| 10 ≦ year < 20 | 22,610 | 23.3 | ||

| 20 years ≦ | 24,576 | 25.3 | ||

| Unknown | 9672 | 9.9 | ||

| Number of years living in the current place of residence (years) | 94,899 | 3 (1–5) | ||

| Floor living on/number of floors in the apartment building | 63,509/67,230 | 2 (1–3)/2 (2–4) | ||

| Number of rooms in the house/apartment | 97,293 | 3 (3–5) | ||

| Size of the floor space of the house/apartment (m2) | 40,321 | 67 (50–100) | ||

| House renovation/interior finishing after getting pregnant | 97,242 | |||

| Yes (%) | 3076 | 3.2 | ||

| Living in an all-electric house/building | 97,276 | |||

| Yes (%) | 18,317 | 18.8 | ||

| Small refuse incinerator on the premises of home | 97,408 | |||

| Yes, but it is no longer used (%) | 1298 | 1.3 | ||

| Yes, it is used still (%) | 2632 | 2.7 | ||

| Use of a water purifier on a water faucet | 97,427 | |||

| Yes (%) | 27,539 | 28.3 | ||

| Mold | Mold growing somewhere in the house | 96,853 | ||

| Yes (%) | 60,946 | 62.9 | ||

| Number of responses | 98,051 | |||

| Kitchen (yes, %) | 10,869 | 11.1 | ||

| Living room (yes, %) | 2020 | 2.1 | ||

| Mother’s bedroom (yes, %) | 5306 | 5.4 | ||

| Other bedroom (yes, %) | 1122 | 1.1 | ||

| Bathroom (yes, %) | 57,252 | 58.4 | ||

| Lavatory (yes, %) | 4278 | 4.4 | ||

| Other place (yes, %) | 2886 | 2.9 | ||

| Pet | Having a pet currently | 97,538 | ||

| Yes (%) | 22,483 | 23.1 | ||

| Number of responses | 98,051 | |||

| Cat (yes, %) | 6852 | 7.0 | ||

| Bird (yes, %) | 682 | 0.7 | ||

| Dog (kept in- and outside of residence, yes, %) | 13,597 | 13.9 | ||

| Hamster (yes, %) | 1018 | 1.0 | ||

| Turtle (yes, %) | 1166 | 1.2 | ||

| Others (yes, %) | 4076 | 4.2 | ||

| Air conditioning | Appliance mainly used to cool rooms in the house/apartment | 97,618 | ||

| Air conditioner | 70,702 | 72.4 | ||

| Electric fan | 24,223 | 24.8 | ||

| Others | 281 | 0.3 | ||

| Nothing | 2412 | 2.5 | ||

| Use of a humidifier during the last year | 97,634 | |||

| Yes (%) | 56,469 | 57.8 | ||

| Use of a dehumidifier/dehumidifying function of an air conditioner during the last year | 97,564 | |||

| Yes (%) | 58,808 | 60.3 | ||

| Use of an air-cleaning device | 97,632 | |||

| Yes (%) | 50,235 | 51.5 | ||

| Heating appliance used in the living room during winter (yes, %) | 92,257 | |||

| Yes (%) | 91,587 | 99.3 | ||

| Type of heating equipment in living room | 98,051 | |||

| Kerosene heater/kerosene fan heater | 48,454 | 49.4 | ||

| Gas heater/gas fan heater | 7800 | 8.0 | ||

| Kerosene/gas heater (with a chimney or an exhaust pipe that reaches outside of house) | 1514 | 1.5 | ||

| Air conditioner/steam heater/oil heater | 53,741 | 54.8 | ||

| Electric “kotatsu” (a table with an electric heater underneath, with a quilt)/electric heater/electric carpet/other electric heating equipment | 58,347 | 59.5 | ||

| Central heating/floor heating | 5831 | 5.9 | ||

| Charcoal/briquette “kotatsu” or “hibachi” (Japanese heating appliance using charcoal as fuel) | 669 | 0.7 | ||

| Other equipment | 2404 | 2.5 | ||

| Use of any equipment to heat a bed during winter | 96,376 | |||

| Yes (%) | 30,262 | 31.4 | ||

| Type of heating equipment in bed | 98,051 | |||

| Electric “anka” (bed warmer) | 2969 | 3.0 | ||

| Electric blanket | 12,608 | 12.9 | ||

| Hot water bottle | 16,351 | 16.7 | ||

| Other equipment | 1800 | 1.8 | ||

| Cleaning | Materials covering the flooring of the living room | 97,475 | ||

| Tatami (Japanese straw floor covering) | 11,285 | 11.6 | ||

| Carpet on tatami | 8853 | 9.1 | ||

| Flooring/wooden flooring/tiles | 34,574 | 35.5 | ||

| Carpet on flooring/wooden flooring/tiles | 40,990 | 42.1 | ||

| Other | 1773 | 1.8 | ||

| Frequency of cleaning the floor of the living room with a vacuum cleanera | 97,616 | |||

| Everyday | 17,156 | 17.6 | ||

| A few times a week | 42,918 | 44.0 | ||

| Once a week | 29,605 | 30.3 | ||

| 1–2 times a month | 5784 | 5.9 | ||

| A few times a year | 915 | 0.9 | ||

| Almost never or never | 1238 | 1.3 | ||

| Frequency of cleaning the floor of the bedroom with a vacuum cleanera | 97,617 | |||

| Everyday | 10,824 | 11.1 | ||

| A few times a week | 38,693 | 39.6 | ||

| Once a week | 34,392 | 35.2 | ||

| 1–2 times a month | 10,371 | 10.6 | ||

| A few times a year | 1718 | 1.8 | ||

| Almost never or never | 1619 | 1.7 | ||

| Frequency of cleaning the “futon” (Japanese mattress and blanket for bedding) with a vacuum cleanera | 97,451 | |||

| A few times a week | 3797 | 3.9 | ||

| Once a week | 10,763 | 11.0 | ||

| 1–2 times a month | 16,369 | 16.8 | ||

| A few times a year | 12,190 | 12.5 | ||

| Almost never or never | 54,332 | 55.8 | ||

| Frequency of airing the “futon” (Japanese mattress and blanket for bedding)a | 97,446 | |||

| A few times a week | 8595 | 8.8 | ||

| Once a week | 23,081 | 23.7 | ||

| 1–2 times a month | 36,214 | 37.2 | ||

| A few times a year | 18,216 | 18.7 | ||

| Almost never or never | 11,340 | 11.6 | ||

| Use of anti-mite covers for “futon” or bedding after getting pregnant | 96,946 | |||

| Yes (%) | 7767 | 8.0 | ||

| Outdoor time | Spending time outdoors (hours per day) | 93,944 | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | |

| Mobile phone | Talk time (per day) | 97,648 | ||

| I do not have a mobile phone | 144 | 0.1 | ||

| None | 10,011 | 10.3 | ||

| Less than 10 min | 69,381 | 71.1 | ||

| For 10–60 min | 15,722 | 16.1 | ||

| More than 1 h | 2390 | 2.4 | ||

| Number of emails sent and received (per day) | 97,606 | |||

| I do not have a mobile phone | 154 | 0.2 | ||

| None | 2009 | 2.1 | ||

| Less than 10 times | 83,153 | 85.2 | ||

| More than 10 times | 12,290 | 12.6 |

N number of responses

aAverage throughout the year

Table 6 shows the use of household chemicals during pregnancy (MT2). Most of the participants used a deodorizer or an air freshener, especially in the lavatory. Insect repellents and insecticides were used widely in households: about 60% used “moth repellent for clothes in the closet,” whereas 32% applied “spray insecticide indoors” or “mosquito coil or an electric mosquito repellent mat.” About 40% of the participants had used “medicated soap or antibacterial soap,” “cosmetics with strong perfume or a fragrance,” and “nail polish” at least once since becoming pregnant. The incidence of “coloring or perming hair at a beauty salon” during pregnancy was 50%. Combined with the frequency of “coloring or perming hair at home,” the results indicate that most subjects carried out hair treatments during pregnancy.

Table 6.

The use of household chemicals during pregnancy (MT2)

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of refueling a car with gasoline at a self-service gas station | 97,672 | |

| Everyday | 147 | 0.2 |

| 4–6 times a week | 258 | 0.3 |

| 2–3 times a week | 2354 | 2.4 |

| Once a week | 8957 | 9.2 |

| 1–3 times a month | 31,912 | 32.7 |

| Less than once a month | 19,518 | 20.0 |

| Never | 34,526 | 35.3 |

| Use of a deodorizer or an air freshener | ||

| Lavatory | 97,531 | |

| Yes (%) | 82,658 | 84.8 |

| Living room or bedroom | 97,495 | |

| Yes (%) | 55,267 | 56.7 |

| Use of a moth repellent for clothes in the closet | 97,513 | |

| Yes, continuously | 21,041 | 21.6 |

| Yes, sometimes | 36,626 | 37.6 |

| Never | 39,846 | 40.9 |

| Use of a spray insecticide indoors | 96,799 | |

| Yes (%) | 30,843 | 31.9 |

| Frequency of using a spray insecticide indoors | 31,676 | |

| Everyday | 572 | 1.8 |

| A few times a week | 3490 | 11.0 |

| Once a week | 1962 | 6.2 |

| 1–3 times a month | 6368 | 20.1 |

| Less than once a month | 19,284 | 60.9 |

| Use of a mosquito coil or an electric mosquito repellent mata | 97,187 | |

| Yes (%) | 30,897 | 31.8 |

| Frequency of using a mosquito coil or electric mosquito repellent mata | 31,282 | |

| Everyday | 8986 | 28.7 |

| A few times a week | 10,943 | 35.0 |

| Once a week | 2175 | 7.0 |

| 1–3 times a month | 4193 | 13.4 |

| Less than once a month | 4985 | 15.9 |

| Use of a liquid insecticide for maggot and mosquito larva | 97,618 | |

| Yes (%) | 710 | 0.7 |

| Frequency of using a liquid insecticide for maggot and mosquito larva | 706 | |

| Everyday | 27 | 3.8 |

| A few times a week | 66 | 9.3 |

| Once a week | 56 | 7.9 |

| 1–3 times a month | 139 | 19.7 |

| Less than once a month | 418 | 59.2 |

| Use of an herbicide or a gardening pesticide in a garden, balcony, or farm | 97,425 | |

| Yes (%) | 8600 | 8.8 |

| Frequency of using an herbicide or a gardening pesticide in a garden, balcony, or farm | 8534 | |

| Everyday | 83 | 1.0 |

| A few times a week | 201 | 2.4 |

| Once a week | 211 | 2.5 |

| 1–3 times a month | 1363 | 16.0 |

| Less than once a month | 6676 | 78.2 |

| Spraying insect repellent on clothes or putting lotion on skin | 97,152 | |

| Yes (%) | 23,829 | 24.5 |

| Frequency of spraying insect repellent on clothes or putting lotion on skin | 24,127 | |

| Everyday | 517 | 2.1 |

| A few times a week | 4701 | 19.5 |

| Once a week | 2134 | 8.8 |

| 1–3 times a month | 5592 | 23.2 |

| Less than once a month | 11,183 | 46.4 |

| Use of smoke insecticide indoors | 97,500 | |

| Yes (%) | 6578 | 6.7 |

| Use of a waterproof spray on clothes or shoes | 97,468 | |

| Yes (%) | 11,005 | 11.3 |

| Use of medicated soap or antibacterial soap | 97,339 | |

| Yes (%) | 41,178 | 42.3 |

| Use of a body deodorant | 97,430 | |

| Yes (%) | 32,951 | 33.8 |

| Use of cosmetics with strong perfume or a fragrance | 97,588 | |

| Quite often | 2737 | 2.8 |

| Sometimes | 14,613 | 15.0 |

| Rarely | 19,465 | 19.9 |

| Never | 60,773 | 62.3 |

| Manicuring or using nail polish | 97,608 | |

| Quite often | 5647 | 5.8 |

| Sometimes | 18,313 | 18.8 |

| Rarely | 14,332 | 14.7 |

| Never | 59,316 | 60.8 |

| Use of hair coloring products (e.g., hair dye) or perm solutions at home | 97,616 | |

| Quite often | 1246 | 1.3 |

| Sometimes | 11,801 | 12.1 |

| Rarely | 9185 | 9.4 |

| Never | 75,384 | 77.2 |

| Coloring or perming hair at a beauty salon | 97,585 | |

| Quite often | 3167 | 3.2 |

| Sometimes | 28,750 | 29.5 |

| Rarely | 17,100 | 17.5 |

| Never | 48,568 | 49.8 |

| Use of sunscreen | 97,635 | |

| Quite often | 31,144 | 31.9 |

| Sometimes | 27,038 | 27.7 |

| Rarely | 9622 | 9.9 |

| Never | 29,831 | 30.6 |

| Using drug for treatment of scabies or lice | 97,613 | |

| Yes (%) | 558 | 0.6 |

N number of valid responses

aContinuously for more than a few hours

Discussion

We developed an in-house exposure questionnaire for the use in JECS since there were no standardized ones available. Almost two identical questionnaires were administered during pregnancy. The exposure data included dwelling conditions, indoor environment, daily life consumer product uses, and occupation. To our knowledge, this is the first of its kind in Japan to characterize over 100,000 pregnant women’s exposure data by the questionnaire. The mean gestational age (SD) at the time of the MT1 questionnaire responses was 16.4 (8.0), which means about half of the participants responded the MT1 questionnaire during the second-trimester period of pregnancy or later. We intended to recruit the participants in early pregnancy but did not restrict to be in the first trimester. Some of the participants were registered at their mid to late pregnancy. When we exclude the responses from the mothers who responded during their gestational ages greater than 16 weeks from the MT1 questionnaire data analysis, the results were similar to those presented in Table 1 (data not shown). The timing of the questionnaire response must be taken into account when researchers use the MT1 questionnaire data for later analysis.

Most of the participants had little occupational exposure to chemicals during pregnancy, while 30–40% of the participants reported the use of personal care products and household pesticide application. Of the participants, 20–30% had consumed convenience foods such as fast foods and retort pouch foods more than once a week within the month prior to the survey, suggesting exposure to chemicals in preservatives or food-packaging materials such as phthalates and bisphenols. Phthalates and bisphenols are suspected endocrine disrupters and have been adversely associated with child health. This information can be used not only to analyze the association between environmental factors and children’s health but also in the future planning of the JECS exposure assessment using biomonitoring.

The Danish National Birth Cohort reported that heavy object lifting was associated with an increased risk of preterm birth in a dose–response manner [15]. Although no exposure–response relationship was observed for fetal death, Mocevic et al. [16] found an increased risk of stillbirth (fetal death ≥ 22 gestational weeks) among those who lifted more than 200 kg/day. In the Danish National Birth Cohort, 16,604 women (26.4%) carried heavy loads (> 20 kg) at work and 475 women (2.9%) lifted more than 1000 kg per day [15]. The Labor Standards Act protects pregnant Japanese women aged ≥ 18 years from tasks that involve heavy object lifting (continuing work, > 20 kg; intermittent work, > 30 kg). In JECS, only 5078 (5.3%) women in the MT1 questionnaire and 3744 (3.9%) women in the MT2 questionnaire lifted loads greater than 20 kg at work (Table 1), though most women in JECS lifted loads greater than 10 kg (including a child) (Table 2).

Various case-control studies have shown the relationship between maternal occupational exposure to solvents and some subtypes of malformations, mostly oral clefts [17–20]. Significant associations were also reported between maternal exposure to solvents and cardiac malformations [21, 22] and neural tube defects [20]. A review of the results of 49 studies showed that maternal occupational exposure to chemicals (lead and pesticides) was associated with time to pregnancy [23]. Snijder et al. [24] observed in the Netherlands (the Generation R Study) that maternal occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, phthalates, alkylphenolic compounds, and pesticides influenced adversely several domains of fetal growth (fetal weight). In JECS, the occupational use of insecticides, organic solvents, and metals (sum of chromium, arsenic and cadmium, lead, and mercury) more than once a month was reported by 7.1%, 5.8%, and 0.6% of the participants, respectively (Table 3). These frequencies were slightly higher than those in the Generation R Study (n = 4680) in which the prevalence of maternal occupational use of pesticides, organic solvents, and metals were 0.5%, 4.7%, and 1.1%, respectively [24]. With the exception of mercury, occupational exposure to these chemicals was more prevalent in the JECS participants than in the Generation R participants.

Though exposure information obtained from questionnaires could be considered also an important variable, there are few validated standard questionnaire sets. As shown in Table 3, the kappa-coefficients demonstrate mostly fair to moderate agreement between the MT1 and MT2 questionnaires. Since all kappa scores resulted in < 0.61, it suggested that pregnant women could change the chemical use under occupation during pregnancy.

The National Health and Nutrition Survey of Japan [25] reported that the frequency of eating out at a restaurant was 25.1% in total women, 47.3% in women 20–29 years old, and 40.4% in women 30–39 years old. The survey reported also that the frequency of eating pre-packed foods was 39.4% in total women more than 20 years old. In JECS, the frequencies of eating out and eating pre-packed foods more than once a week were 45.7% and 37.6%, respectively. This result is similar to that of the National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan, indicating that this part of the questionnaire is valid also.

The 2013 Housing and Land Survey of Japan reported that the proportions of wooden housing and non-wooden, such as steel-frame, housing were 58% and 42%, respectively [26]. The JECS results were similar to those of that survey with wooden and non-wooden dwellings reported by 54% and 45% of participants, respectively. In 1981, the Building Standards Act of Japan was revised to enforce new earthquake-resistance standards. The proportion of housing built after 1981 was 64.9% in the national survey (2013), while that of housing less than 20 years of age was 64.8% in JECS. The mean number of rooms and dwelling area in the national survey (2013) were 4.59 rooms and 94.42 m2 per house, respectively. The mean number of rooms and dwelling area in JECS were 3.89 rooms and 82.32 m2 per house, respectively. These results showed that the JECS participants lived in smaller and relatively newer houses compared with respondents to the national survey (2013).

In the questionnaire-based maternal environmental exposure assessment (n = 987) of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project, the rate of household pesticide application was 7.1% (70/987) in respondents from Brazil, China, India, Italy, Kenya, Oman, UK, and the USA [27]. In JECS, the rates of maternal use of moth repellent for clothes, indoor insecticide spray, mosquito coils/mats, liquid insecticides, smoke insecticides, and herbicides were 59%, 32%, 32%, 0.7%, 6.7%, and 8.8%, respectively. People in Japan appear to use more types of pesticides and to use them at a higher rate than people in the abovementioned countries. This indicates the importance of biomonitoring of pesticide chemicals in JECS.

There are some limitations of the JECS exposure assessment questionnaires. Firstly, the self-administered questionnaires were developed in-house by the JECS Programme Office and did not go through any validation process using biological or environmental measurements. Much of the exposure data could only be obtained using questionnaires; the accuracy and reliability of which could not be evaluated. However, some of our results were similar to those of national surveys on such topics as dwelling conditions and dietary habits; accordingly, we assumed that these parts of our questionnaires, at least, were somewhat reliable. The other topics had not been studied previously in Japan in either national surveys or scientific publications. To our knowledge, therefore, these results constitute the first report on the exposure status of pregnant women in Japan. Secondly, we investigated the two questionnaires reliability by administering nearly identical questionnaires in MT1 and MT2. However, there were subtle differences in how the questions were expressed in the MT1 and MT2 questionnaires (for details see Additional file 1), which may have affected the responses. In a future study, we plan to verify the questionnaire as thoroughly as possible using quantitative instruments such as biomonitoring and environmental measurements. Lastly, there were some extreme values observed among the questionnaire responses, e.g., 99 years for the “number of years living in the current place of residence,” 91/83 as “the floor living on/number of floors in the apartment building,” 93 for the “number of rooms in the house/apartment,” and 999 m2 for the “size of the floor space of the house/apartment.” Such values were observed in less than 0.01% of cases. We did not exclude these possible outliers from the analysis presented in this paper since there was no way for us to verify the accuracy of these responses.

This result will be used to design future JECS exposure assessments with biomonitoring. The questionnaire data will also be used to investigate the associations between environmental factors and children’s health and development when data comes available. Some parts of the questionnaire will be validated using biomonitoring data. Such questionnaire items are of great importance for other epidemiological and exposure studies since there are few validated exposure questionnaires. The validate questionnaire can also be used for a national biomonitoring program as a tool to collect exposure source information.

Conclusions

We characterized the environmental exposures of the JECS participants using two maternal questionnaires. Most of the mothers had little occupational exposure to chemicals during pregnancy. The household use of pesticides was more frequent in JECS than in studies in other countries. It will also be used to investigate the associations between environmental factors and children’s health in the future.

Additional file

Supplementary information about questionnaire items for Tables 1 to 6. (PDF 126 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all the JECS study participants. We sincerely express our appreciation to the co-operating health care providers. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Hiroshi Satoh (Food Safety Commission, Cabinet Office, Tokyo, Japan) who was the former principal investigator of JECS.

Members of the JECS group, as of April 2018 (principal investigator, Toshihiro Kawamoto) were as follows: Yukihiro Ohya (Medical Support Center for JECS, National Centre for Child Health and Development, Tokyo, Japan), Reiko Kishi (Hokkaido Regional Center for JECS, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan), Nobuo Yaegashi (Miyagi Regional Center for JECS, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan), Koichi Hashimoto (Fukushima Regional Center for JECS, Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima, Japan), Chisato Mori (Chiba Regional Center for JECS, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan), Shuichi Ito (Kanagawa Regional Center for JECS, Yokohama City University, Yokohama, Japan), Zentaro Yamagata (Koshin Regional Center for JECS, University of Yamanashi, Yamanashi, Japan), Hidekuni Inadera (Toyama Regional Center for JECS, University of Toyama, Toyama, Japan), Michihiro Kamijima (Aichi Regional Center for JECS, Nagoya City University, Nagoya, Japan), Takeo Nakayama (Kyoto Regional Center for JECS, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan), Hiroyasu Iso (Osaka Regional Center for JECS, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan), Masayuki Shima (Hyogo Regional Center for JECS, Hyogo College of Medicine, Nishinomiya, Japan), Yasuaki Hirooka (Tottori Regional Center for JECS, Tottori University, Yonago, Japan), Narufumi Suganuma (Kochi Regional Center for JECS, Kochi University, Nankoku, Japan), Koichi Kusuhara (Fukuoka Regional Center for JECS, Kyushu University, Kitakyushu, Japan), and Takahiko Katoh (South Kyushu/Okinawa Regional Center for JECS, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan).

Funding

The Japan Environment and Children’s Study was funded by the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. The Ministry of the Environment does not ever content of this article. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the above government agency.

Availability of data and materials

It is not possible to share the raw research data publicly since data privacy could be compromised. Data are unsuitable for public deposition due to ethical restrictions and legal framework of Japan. It is prohibited by the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (Act No. 57 of 30 May 2003, amendment on 9 September 2015) to publicly deposit the data containing personal information. Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects enforced by the Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare also restricts the open sharing of the epidemiologic data.

Abbreviations

- JECS

Japan Environment and Children’s Study

- MT1

First trimester

- MT2

Second/third trimester

Authors’ contributions

SN, SY, MO, JY, KT, ES, HN, TK, and JECS group designed and conducted the survey. MI, SN, TM, and AT performed the statistical analysis and interpretation of the results and drafted the manuscript. TM, TI, YK, HN, and JECS group critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript as submitted.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ministry of the Environment’s Institutional Review Board on Epidemiological Studies as well as the ethics committees of all participating institutions. All the participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Miyuki Iwai-Shimada, Email: iwai.miyuki@nies.go.jp.

Shoji F. Nakayama, Phone: +81-298-50-2786, Email: fabre@nies.go.jp

Tomohiko Isobe, Email: isobe.tomohiko@nies.go.jp.

Takehiro Michikawa, Email: tmichikawa@nies.go.jp.

Shin Yamazaki, Email: yamazaki.shin@nies.go.jp.

Hiroshi Nitta, Email: nitta@nies.go.jp.

Ayano Takeuchi, Email: ayanotakeuchi@keio.jp.

Yayoi Kobayashi, Email: kobayashi.yayoi@nies.go.jp.

Kenji Tamura, Email: ktamura@nies.go.jp.

Eiko Suda, Email: suda.eiko@nies.go.jp.

Masaji Ono, Email: onomasaj@nies.go.jp.

Junzo Yonemoto, Email: yonemoto@nies.go.jp.

Toshihiro Kawamoto, Email: kawamott@med.uoeh-u.ac.jp.

the Japan Environment and Children’s Study Group, Email: jecs-en@nies.go.jp.

the Japan Environment and Children’s Study Group:

Toshihiro Kawamoto, Yukihiro Ohya, Reiko Kishi, Nobuo Yaegashi, Koichi Hashimoto, Chisato Mori, Shuichi Ito, Zentaro Yamagata, Hidekuni Inadera, Michihiro Kamijima, Takeo Nakayama, Hiroyasu Iso, Masayuki Shima, Yasuaki Hirooka, Narufumi Suganuma, Koichi Kusuhara, and Takahiko Katoh

References

- 1.Kawamoto T, Nitta H, Murata K, Toda E, Tsukamoto N, Hasegawa M, et al. Rationale and study design of the Japan environment and children's study (JECS) BMC Public Health. 2014;14:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michikawa Takehiro, Nitta Hiroshi, Nakayama Shoji F., Yamazaki Shin, Isobe Tomohiko, Tamura Kenji, Suda Eiko, Ono Masaji, Yonemoto Junzo, Iwai-Shimada Miyuki, Kobayashi Yayoi, Suzuki Go, Kawamoto Toshihiro. Baseline Profile of Participants in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS) Journal of Epidemiology. 2018;28(2):99–104. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20170018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michikawa T, Nitta H, Nakayama SF, Ono M, Yonemoto J, Tamura K, et al. The Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS): a preliminary report on selected characteristics of approximately 10 000 pregnant women recruited during the first year of the study. J Epidemiol. 2015;25:452–458. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20140186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO . Principles for evaluating health risks in children associated with exposure to chemicals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsen J, Melbye M, Olsen SF, Sorensen TI, Aaby P, Andersen AM, et al. The Danish National Birth Cohort--its background, structure and aim. Scand J Public Health. 2001;29:300–307. doi: 10.1177/14034948010290040201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magnus P, Irgens LM, Haug K, Nystad W, Skjaerven R, Stoltenberg C, et al. Cohort profile: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:1146–1150. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magnus P, Birke C, Vejrup K, Haugan A, Alsaker E, Daltveit AK, et al. Cohort Profile Update: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:382–388. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaddoe VW, van Duijn CM, van der Heijden AJ, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Steegers EA, et al. The Generation R Study: design and cohort update until the age of 4 years. Eur J Epidemiol. 2008;23:801–811. doi: 10.1007/s10654-008-9309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park B, Choi EJ, Ha E, Choi JH, Kim Y, Hong YC, et al. A study on the factors affecting the follow-up participation in birth cohorts. Environ Health Toxicol. 2016;31:e2016023. doi: 10.5620/eht.e2016023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–2260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez FD. Genes, environments, development and asthma: a reappraisal. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:179–184. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00087906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vrijheid M. The exposome: a new paradigm to study the impact of environment on health. Thorax. 2014;69:876–878. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Runge SB, Pedersen JK, Svendsen SW, Juhl M, Bonde JP, Nybo Andersen AM. Occupational lifting of heavy loads and preterm birth: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70:782–788. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-101173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mocevic E, Svendsen SW, Jorgensen KT, Frost P. Bonde JP occupational lifting, fetal death and preterm birth: findings from the Danish National Birth Cohort using a job exposure matrix. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laumon B, Martin JL, Collet P, Bertucat I, Verney MP, Robert E. Exposure to organic solvents during pregnancy and oral clefts: a case-control study. Reprod Toxicol. 1996;10:15–19. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(95)02013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorente C, Cordier S, Bergeret A, De Walle HE, Goujard J, Ayme S, et al. Maternal occupational risk factors for oral clefts. Occupational Exposure and Congenital Malformation Working Group. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000;26:137–145. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chevrier C, Dananche B, Bahuau M, Nelva A, Herman C, Francannet C, et al. Occupational exposure to organic solvent mixtures during pregnancy and the risk of non-syndromic oral clefts. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63:617–623. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.024067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desrosiers TA, Lawson CC, Meyer RE, Richardson DB, Daniels JL, Waters MA, et al. Maternal occupational exposure to organic solvents during early pregnancy and risks of neural tube defects and orofacial clefts. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69:493–499. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2011-100245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilboa SM, Desrosiers TA, Lawson C, Lupo PJ, Riehle-Colarusso TJ, Stewart PA, et al. Association between maternal occupational exposure to organic solvents and congenital heart defects, National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997-2002. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69:628–635. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2011-100536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tikkanen J, Heinonen OP. Cardiovascular malformations and organic solvent exposure during pregnancy in Finland. Am J Ind Med. 1988;14:1–8. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700140102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snijder CA, te Velde E, Roeleveld N, Burdorf A. Occupational exposure to chemical substances and time to pregnancy: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18:284–300. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snijder CA, Roeleveld N, Te Velde E, Steegers EA, Raat H, Hofman A, et al. Occupational exposure to chemicals and fetal growth: the Generation R Study. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:910–920. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan . National Health and Nutrition Survey of Japan. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Statistic Bureau. Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications of Japan . Housing and Land Survey of Japan. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eskenazi B, Bradman A, Finkton D, Purwar M, Noble JA, Pang R, et al. A rapid questionnaire assessment of environmental exposures to pregnant women in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. BJOG. 2013;120(Suppl 2):129–138. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information about questionnaire items for Tables 1 to 6. (PDF 126 kb)

Data Availability Statement

It is not possible to share the raw research data publicly since data privacy could be compromised. Data are unsuitable for public deposition due to ethical restrictions and legal framework of Japan. It is prohibited by the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (Act No. 57 of 30 May 2003, amendment on 9 September 2015) to publicly deposit the data containing personal information. Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects enforced by the Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare also restricts the open sharing of the epidemiologic data.