Abstract

The foot is at the base of the antigravity control system (postural or equilibrium system) that allows the man to assume the upright posture and to move in the space. This podalic cohesion is achieved by the capsulo-ligamentous and aponeurotic formations to which are added the muscular formations with functions of “active ligaments” and postural. A three-dimensional (3D) finite element model of human foot was developed using the real foot skeleton and soft tissue geometry, obtained from the 3D reconstruction of MR images. The plantar fascia and the other main ligaments were simulated using truss elements connected with the bony surfaces. Bony parts and ligaments were encapsulated into a skin of soft tissues, imposing a linear elastic behavior of material in the first case and the hyperelastic law in the second. The model was tested by applying a load of 350 N on the top of the talus and the reaction force applied on the Achilles tendon equal to 175 N acting, and putting it in contact with a rigid wall. The results evidence that the most stressed areas, localized around the calcaneus following a trajectory that includes the cuboid and spreading into metatarsals and first phalanges. The foot is a “spatial” structure perfectly designed to absorb and displace the forces, brought back to the infinite planes of the space.

Keywords: Foot model, CAD, FE analysis

1. Introduction

The human body is a system of unstable equilibrium; the height of the center of gravity (ideally prior to the third lumbar vertebra) compared to a narrow base and the structure composed of a succession of articulated segments, are factors of instability. Only a vigilant control (postural tonic system) succeeds, in this condition, to seek the stable dynamic equilibrium in the erected station and the dynamic equilibrium unstable during the locomotion (which allows the transformation of the potential energy into kinetic energy). This happens mainly thanks to an information service (cutaneous exteroceptors and proprioceptors) so precise and timely that they allow very valid answers with energetically economical interventions (not detectable electromyographically) by muscles with a predominance of red fibers. This is the most important informational event because it provides the man with the privilege of adapting to the most varied environmental conditions. The foot is a “spatial” structure that is designed to absorb and displace the forces, relative to the infinite planes of space. The structure of the foot is a unique masterpiece of architecture, or rather of biomechanics, with its 26 bones, 33 joints and 20 muscles.

Functionally and structurally, it is possible to divide the foot in:

-

-

Retro pod formed by an astragalus and calcaneus, a central device of the biomechanical control of gravity;

-

-

Forefoot formed by scaphoid, cuboid, three cuneiforms (also called midfoot, the midfoot plus the retro pod forms the tarsus), five metatarsal rays (metatarsal) and the phalanges of the five fingers; acts as an “adapter and reactor”.

The foot, in its role of “antigravity base”, at first makes contact with the support surface by adapting to it, releasing itself, then stiffens, becoming a lever to “react” to the surface itself. The foot must then alternate the release condition with the stiffening condition. In fact, the retro pod and forefoot are arranged in planes intersecting in a variable way. In the ideal condition, the hind foot is placed vertically and the forefoot horizontally (on a horizontal supporting surface). On foot under load the torsion between the back and forefoot is attenuated in relaxation (the foot becomes a modeling platform) and is accentuated in the stiffening (the foot becomes a lever). The astragalus rotating outside solidly with the bones of the leg rises on the heel, thus closing the mid-tarsic articulation; the hind foot is verticalized. The forefoot adhering tenaciously to the ground reacts to the twisting forces applied on the hind foot, the foot is then stiffened. The effects of soft tissue compliance and other structural characteristics on the stress distribution of the plantar foot surface and bony structures is essential to obtain correct FE simulations. In-shoe pressure sensors and pedobarograph let to measure pressure distributions aging foot and different supports.1,2,3 This kind of experimental technique can guarantee reliable results in terms of pressures registered in the different areas of the foot plantar, but the load transfer mechanism and internal stress states within the soft tissues and the bony structures cannot be well addressed. In order to supplement these experiments, researchers have turned to computational methods. The finite element (FE) analysis has been an adjunct to experimental approach to predict the load distribution between the foot and different supports, which offer additional information such as the internal stresses/strains shielding. Different foot models have been developed, by using certain assumptions or simplifying geometry and joints. It has been shown in the literature that FE models can contribute in familiarizing the effects of thickness and stiffness of plantar soft tissue on plantar pressure distribution.4,5,6

A detailed model of the human foot was realized and tested by loading it with a vertical force of 350 N balanced by the reaction force of 175 N offered by the Achilles's tendon applied on the calcaneus. The isostatic configuration was realized by imposing the contact of the foot with a rigid wall. All the bony and soft parts were modelled as solid tetrahedrons, while for ligaments monodimensional truss elements were used. Linear elastic laws were selected to characterize bones while a hyperplastic law was used for skin. The objective of this study was to develop a comprehensive 3D FE model of the foot to investigate the effect of soft tissue stiffness on the plantar pressure distributions and the internal load transfer between bony structures.

2. Materials and methods

A numerical model of the foot was obtained by matching nuclear magnetic resonance (MRI) for soft tissues, and a computerized tomography (CT) for bones, carried on a normal adult patient (70 [kg] BM), previously used in different analyses.7,8

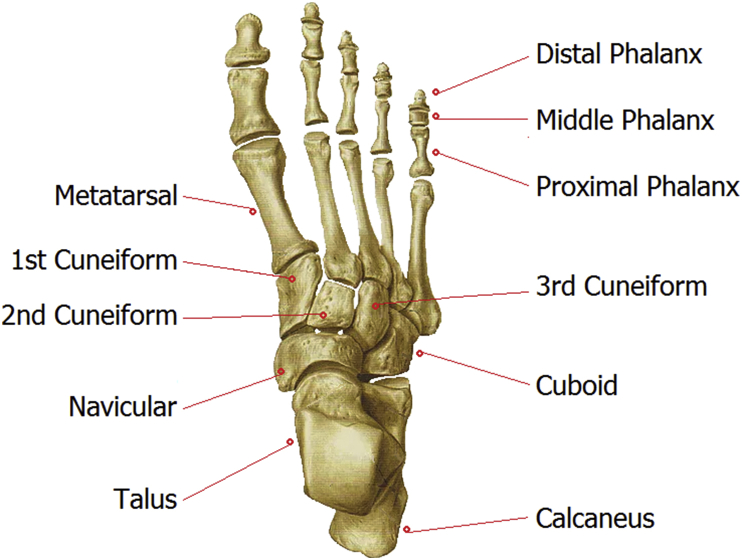

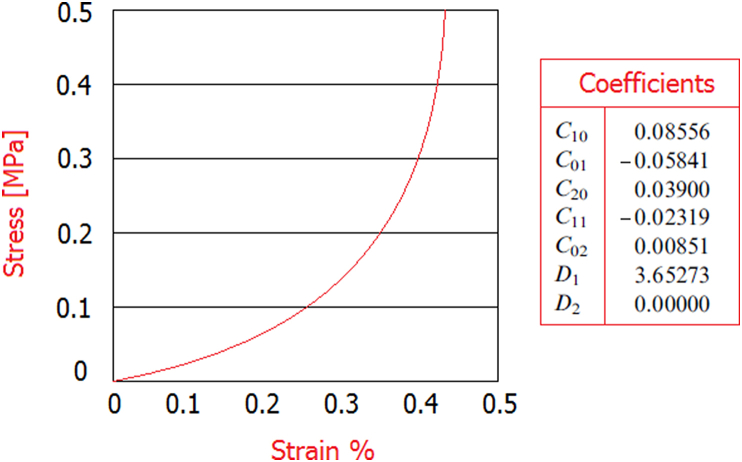

Obtained data were imported into the commercial Hypermesh code by Altair®, where the final finite element model of the foot was reconstructed (167.142 tetrahedrons elements and 43.121 nodes). In Fig. 1 and Table 1 are reported the FE bony segments, skin, and rigid wall including numbers of nodes and elements. Ligaments, other connective tissues, and the plantar fascia were defined, by 98 truss mono dimensional elements, connecting the corresponding attachment points on the bones. All the bony and ligamentous structures were embedded in a volume of soft tissues. To simulate the frictionless contact between the joint surfaces, ABAQUS automated surface-to-surface contact option was used. In literature, different values of Young's modulus have been used to characterize the bony material.9,10 According to the model developed by11 Gefen et al. (2000) adopting the linear elastic material law, the Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio for the bony structures were assigned as 7300 MPa and 0.3, respectively. The mechanical properties of ligaments12 were selected from the literature, see Table 2. The rigid wall was simulated reproducing mechanical properties of steel. The encapsulated soft tissue was defined as nonlinearly elastic material. The stress–strain data on the plantar heel pad from the in vivo ultrasonic measurements13 were used to represent the normal soft tissue stiffness. The hyperelastic material model was used to represent the nonlinear and nearly incompressible nature of the encapsulated soft tissue, while the second-order polynomial strain energy potential was adopted to evaluate the Cij and Di material parameters, see Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Foot anatomy illustration.

Table 1.

FE bony segments including numbers of nodes and elements.

| Bony component | nodes | elements | Bony component | nodes | elements | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talus |  |

4701 | 14095 | 3 t h Cuneiform |  |

5395 | 16191 |

| Calcaneus |  |

3236 | 9926 | 1st to 5 t h Metatarsal |  |

7675 | 23741 |

| Navicular |  |

1595 | 5013 | 1st to 5 t h Toe |  |

6464 | 20896 |

| Cuboid |  |

1286 | 3941 | Skin |  |

10687 | 66853 |

| 1st Cuneiform |  |

1246 | 3808 | Rigid wall |  |

142 | 612 |

| 2nd Cuneiform |  |

694 | 2096 |

Table 2.

Mechanical and geometrical properties of the FE model.

| Component | Element type | Young modulus [MPa] | Poisson's ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bony parts | 3 d Tetrahedrons | 7.300 | 0.3 |

| Soft tissue | 3 d Tetrahedrons | hyperelastic | / |

| ligaments | 1 d Truss | 350 | / |

| Rigid wall | 3 d Tetrahedrons | 210.000 | 0.3 |

Fig. 2.

Stress strain data on the plantar heel pad.

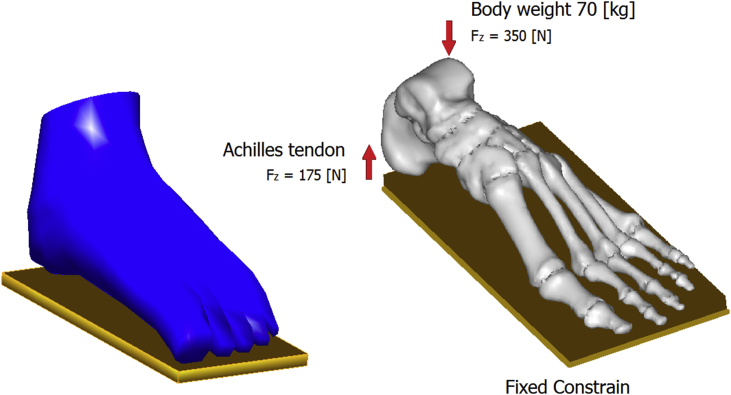

A rigid wall of steel was used as ground support using surface-to-surface contact elements in combination with the penalty algorithm with a normal contact stiffness of 600 N/mm and a friction coefficient of 0.4.14,15 A vertical force of approximately 350 N is applied on the top of the talus corresponding to a BW of 70 kg.16 The vertical upward force of the Achilles tendon, with magnitude of 175 N, was applied at the posterior extreme of the calcaneus, see Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Loading conditions of the FE model.

3. Results

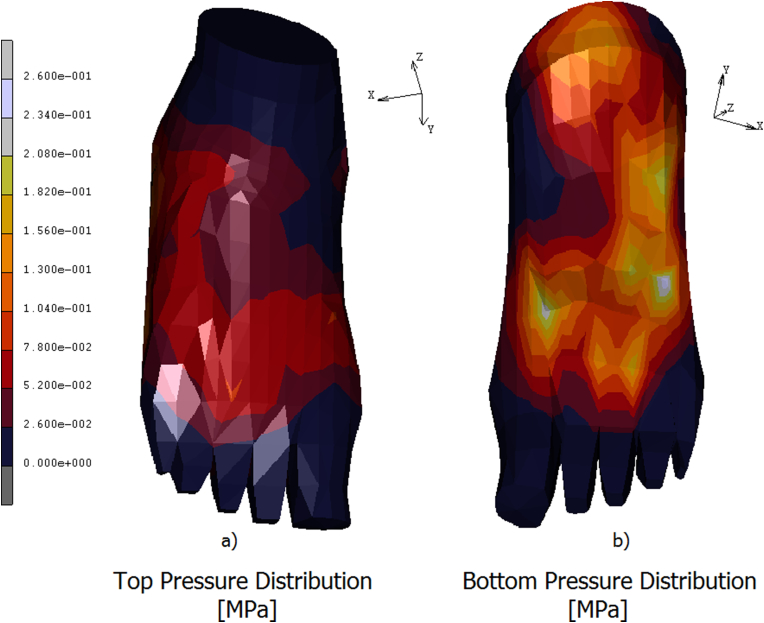

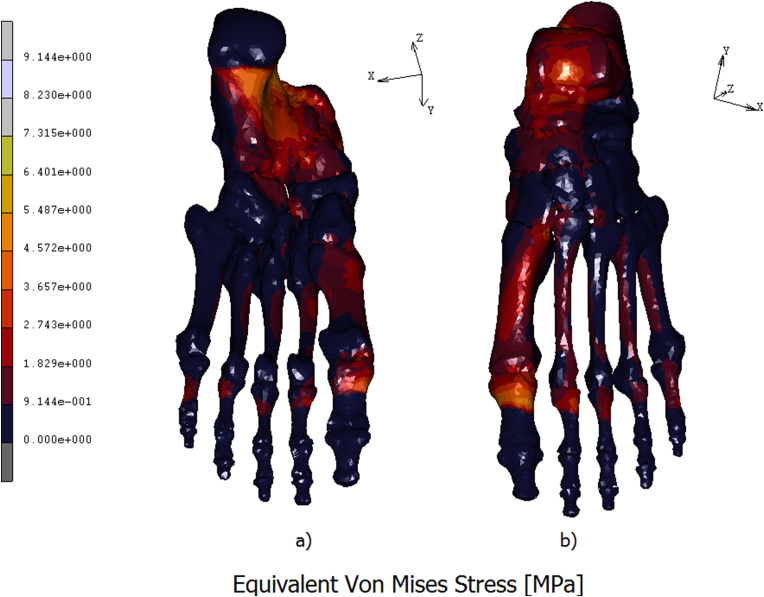

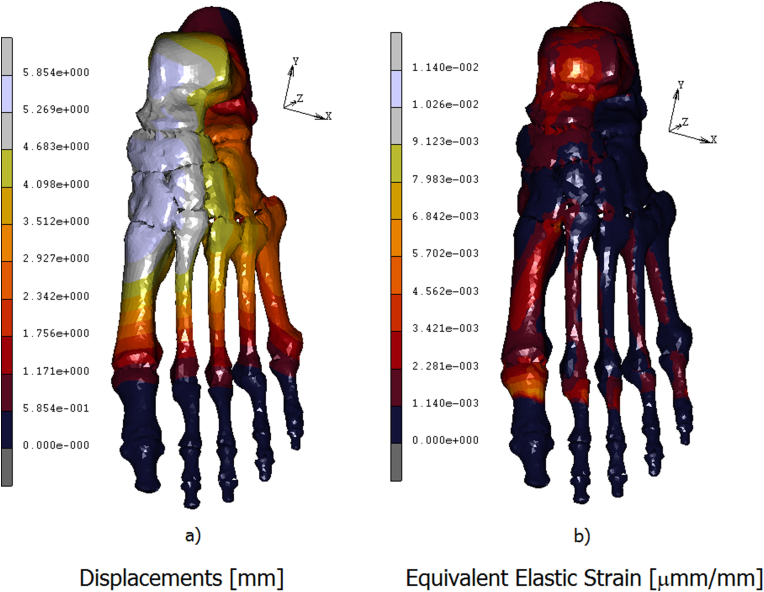

A 3D FE model of the human foot was developed in order to predict the plantar pressure and the internal stresses/strains distribution. In Fig. 4 a) is reported the contour map of the skin on the top of the foot. The stress is mostly concentered on the neck of the foot, reaching values of 0.07 MPa. In Fig. 4 b) is reported the contour stress map evidenced on the bottom of the foot. In this area peaks of pressure acting around 0.26 MPa are reached on calcaneus, on the lateral plantar fascia, and from the first to the fifth metatarsal head regions. The medial plantar fascia appears less stressed with values of pressure aging around 0.05 MPa. In Fig. 5 a) is reported the equivalent von mises contour map evaluated on the top of the bony parts constituting the foot. As it is possible the notice a peak stress of 5.48 MPa is reached on the talus. The metatarsals bones are differently loaded from the first metatarsal, loaded with a stress of about 2.74 MPa, till the fourth one loaded with an equivalent stress of 0.91 MPa. On the first proximal phalange are reached values of 6.40 MPa, following a decreasing trend on the remaining others proximal phalanges where the stress reaches values of 1.82 MPa. In Fig. 5 b) is better evidenced the stress shielding acting on the bony parts. As it is possible to notice the stress reaches its peak on the calcaneus, about 8.23 MPa, spreading on the medial plantar fascia with values of 2.74 MPa. In the metatarsal area, the maximum stress is evidenced by the first metatarsal, about 3.65 MPa, while the other four metatarsal evidence an equivalent stress of 1.82 MPa. A peak of stress is registered on the first proximal phalange equal to 7.31 MPa, gradually decreasing on the remaining others since a value of 1.82 MPa. In Fig. 6a) is reported the contour map of displacements evaluated on the bottom of the bony parts of the foot, maximum values of displacement, registered on the calcaneus and on the medial plantar fascia act around 5,85 mm. In Fig. 6b) is reported the equivalent elastic strain contour map with maximum values of 0.014 μm m/mm evidenced on calcaneus and on the proximal first phalange. In Table 3 are reported the numerical values of equivalent von mises stress, displacements, and equivalent elastic strain calculated in each bony parts.

Fig. 4.

Contour maps of the pressure aging on the top of the foot's skin a) and on the bottom b).

Fig. 5.

Eq. Von Mises stress of the bony parts of the foot calculated on the bottom a) and on the top of the foot b).

Fig. 6.

Contour maps of displacements calculated on the bony parts of the foot a) and Eq. Elastic strain b).

Table 3.

Numerical values of equivalent von mises stress, displacements, and equivalent elastic strain.

| Bony component | Eq. Von Mises Stress [MPa] | Displacement [mm] | Eq. Elastic Strain [mmm/mm] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Talus | 3.65 | 1.85 | 2.28E-03 |

| Calcaneus | 4.57 | 5.85 | 1.14E-02 |

| Navicular | 1.81 | 2.89 | 1.03E-03 |

| Cuboid | 1.82 | 5.36 | 1.25E-04 |

| 1st Cuneiform | 0.91 | 5.56 | 2.31E-03 |

| 2nd Cuneiform | 2.02 | 4.55 | 5.41E-03 |

| 3 t h Cuneiform | 2.91 | 4.21 | 1.48E-04 |

| 1st to 5 t h Metatarsal | 9.14 | 4.59 | 3.36E-03 |

| 1st to 5 t h Toe | 5.31 | 1.78 | 9.45E-03 |

| Skin | 0.26 | 10.2 | 7.89E-02 |

4. Discussion

The capability of the computational model to predict the internal stress within the bony and soft tissue structures makes it a valuable tool to study the biomechanical behavior of the foot. In this study, an accurate 3 d FE model of the foot was reconstructed and tested with a physiological load. Cheung et al.17 carried on a study of the foot conducting experimental and numerical analyses. They found that the predicted plantar pressures were higher than the measured values. As the FE analysis provided solutions of nodal contact pressure rather than an average pressure calculated from nodal force per element's surface area, the F-scan measured peak plantar pressure was therefore expected to be smaller than the predicted values. With increased plantar soft tissue stiffness, the pressure tended to concentrate beneath the heel and the medial metatarsal heads especially for the second and third metatarsals. In all calculated cases, the peak plantar pressure was located at the center of the heel and beneath the second and third metatarsal heads. From the FE prediction, the rate of increase in peak plantar pressure was found to be lower than the corresponding increase of soft tissue stiffness. These numerical values of pressure are comparable to other FE model predictions.5 From the FE predictions, the rate of peak pressure increase tended to decrease with stiffening of soft tissue. Most of the linearly elastic FE models reported used a relatively large value of soft tissue stiffness in their analysis.4 These values overestimated the actual plantar soft tissue stiffness, and reduced the adapting ability of the plantar soft tissue to the supporting surface. Filardi18,19 by conducting an experimental strain analysis on the entire bony leg compared with FE analysis found stresses aging on the foot with values aging from 4.12 to 5 MPa. In another paper, Filardi20 investigated the stress shielding on the different components of the bony chain, by comparing a Varus and valgus knees with a normal knee. The analysis of the entire chain allows having a complete picture of the stress distribution and of the most stressed bones, but more importantly can overcome problems connected with boundary conditions imposed at single bony components, which deeply influence the obtained results. The obtained results reveal interesting consequences deriving by a wrong disposition of parts, which compose the skeletal chain of the human leg. The most dangerous conditions occur in the contact interface between pelvis and hip of the femur, for the valgus knee configuration, and for the Varus one, at the contact interface around the knee zone. The measured stress on the foot is 3.15 MPa in the case of Varus knee, 4.12 MPa in the normal case, and 5.17 MPa in the case of valgus knee. The prediction of peak von Mises stress showed that the mid-shafts of the third and the second metatarsals were the most vulnerable regions. The confined positions of these metatarsals are probably the direct cause of stress concentration. Apart from the mid-shaft of the metatarsals, the junction of the ankle, subtalar and calcaneal–cuboid joints together with the insertion areas of the plantar fascia were also possible sites of stress failure underweight bearing. With stiffening of soft tissue, the load-bearing role of the encapsulated soft tissue increased while the flexibility of the foot reduced. As a result, some of the major foot bones especially the lateral cuneiform and the rear foot bones were relatively unloaded, whereas other foot bones especially the cuboid and lateral metatarsals sustained increased stresses. With minimal increases in peak metatarsal stress, the FE predictions, however found no evidence on increasing the risk of stress failure of foot bones with stiffening of soft tissue. It should be noticed that the effect of tissue stiffening considered in this simulation was simplified by a uniform increase of soft tissue modulus over the completely encapsulated tissue.

5. Conclusions

The developed FE model can be refined to simulate more realistically the actual situations by incorporating nonlinear and viscoelastic material properties for the ligamentous and soft tissue structures. The use of surface contact simulation enables direct comparison of plantar pressure and contact area to the experimental measurement especially for comparison between highly contoured surfaces. The load-bearing characteristic of the ankle–foot structures under different stance phases requires the incorporation of detailed muscular loading, which will be the future development of the FE model. In the real cases, the tissue stiffening may occur in discrete area of foot especially on the plantar foot and may exhibit different degrees of stiffening. The overall biomechanical behavior of diabetic feet may be influenced by other structural changes, such as increased bone deformity, laxity of ligamentous structures or changes in muscular reaction. Besides, the effects of varying plantar soft tissue thickness on plantar pressure and internal stress distribution deserve further investigations. Owing to the use of geometrical accurate model, the generalization of the current FE prediction remains questionable. Simulations of various physiological loading conditions in addition to experimental validations are needed before a conclusion can be made. To simplify the analysis in this study, homogeneous and linearly elastic material properties were assigned to the bony and ligamentous structures and the ligaments within the toes and other connective tissue such as the joint capsules were not considered.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2018.08.037.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Patil K.M., Charanya G., Prabhu G.K. Optical pedobarography for assessing neuropathic feet in diabetic patients—a review. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2002;1:93–103. doi: 10.1177/1534734602001002004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raspovic A., Newcombe L., Lloyd J., Dalton E. Effect of customized insoles on vertical plantar pressures in sites of previous neuropathic ulceration in the diabetic foot. Foot. 2000;10:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lord M., Hosein R. A study of in-shoe plantar shear in patients with diabetic neuropathy. Clin BioMech. 2000;15:278–283. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(99)00076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen W.P., Tang F.T., Ju C.W. Stress distribution of the foot duringmid-stance to push-off in barefoot gait: a 3-D finite element analysis. Clin BioMech. 2001;16:614–620. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gefen A. Plantar soft tissue loading under the medial metatarsals in the standing diabetic foot. Med Eng Phys. 2003;25:491–499. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(03)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitagawa Y., Ichikawa H., King A.I., Begeman P.C. Development of a human ankle/foot model. In: Kajzer J., Tanaka E., Yamada H., editors. Human Biomechanics and Injury Prevention. Springer; Tokyo: 2000. pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filardi V. Finite element analysis of sagittal balance in different morphotype: forces and resulting strain in pelvis and spine. J Orthop. 2017;14(2):268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filardi V. Healing of femoral fractures by the meaning of an innovative intramedullary nail. J Orthop. 2018;15(1):73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montanini R., Filardi V. In vitro biomechanical evaluation of antegrade femoral nailing at early and late postoperative stages. Med Eng Phys. 2010;32(8):889–897. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filardi V., Montanini R. Measurement of local strains induced into the femur by trochanteric Gamma nail implants with one or two distal screws. Med Eng Phys. 2007;29(1):38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gefen A., Megido-Ravid M., Itzchak Y., Arcan M. Biomechanical analysis of the three-dimensional foot structure during ait: a basic tool for clinical applications. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122:630–639. doi: 10.1115/1.1318904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegler S., Block J., Schneck C.D. The mechanical characteristics of the collateral ligaments of the human ankle joint. Foot Ankle. 1988;8:234–242. doi: 10.1177/107110078800800502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemmon D., Shiang T.Y., Hashmi A., Ulbrecht J.S., Cavanagh P.R. The effect of insoles in therapeutic footwear: a finite element approach. J Biomech. 1997;30:615–620. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filardi V. Numerical comparison of two different tibial nails: expert tibial nail and innovative nail. Int J Interact Des Manuf. 2018:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filardi V. Characterization of an innovative intramedullary nail for diaphyseal fractures of long bones. Med Eng Phys. 2017;49:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filardi V. The healing stages of an intramedullary implanted tibia: a stress strain comparative analysis of the calcification process. J Orthop. 2015;12:S51–S61. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheung J.T., Zhang M., Leung A.K., Fan Y. Three-dimensional finite element analysis of the foot during standing—a material sensitivity study. J Biomech. 2005;38:1045–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filardi V., Milardi D. Experimental strain analysis on the entire bony leg compared with FE analysis. J Orthop. 2017;14(1):115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filardi V. FE analysis of stress and displacements occurring in the bony chain of leg. J Orthop. 2014;11(4):157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filardi V. Stress shielding in the bony chain of leg in presence of varus or valgus knee. J Orthop. 2015;12(2):102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.