Abstract

Background/Aims

The modified Graeb Scale (mGS) is a semi-quantitative method to assess the extension of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). The mGS has been shown to prognosticate outcome after ICH in cohorts derived from convenience samples. We evaluated the external validity of mGS in supratentorial ICH-patients from an unselected cohort.

Methods

ICH-patients were included prospectively and consecutively in Lund Stroke Register. Follow-up survival status was obtained from the National Census Office; functional outcome was obtained from the Swedish Stroke Register or medical records. Using multivariate analyses, we examined if mGS was related to 30-day survival or poor functional outcome (modified Rankin Scale ≥ 4) at 90 days.

Results

Of 198 supratentorial ICH-patients, 86 (43%) had IVH (median mGS 12, range 1–28). In multivariate regression analyses, the mGS independently predicted 30-day mortality (per point; OR 1.16; 95% CI 1.06–1.27; p = 0.002) and poor functional outcome (OR 1.11; 95% CI 1.02–1.20; p = 0.011) after ICH. In receiver-operator characteristic analysis, the addition of mGS tended to be associated with a higher prognostic accuracy for survival (area under curve 0.886 vs. not including mGS 0.812; p = 0.053).

Conclusions

The mGS improves outcome prediction after supratentorial ICH beyond other previously established factors in an unselected population.

Keywords: Cerebral hemorrhage, Community-based study, Intracerebral hemorrhage, Outcome assessment, Prognosis, Prognostic predictors, Stroke outcome, Survival, Ventricular grade, Intraventricular hemorrhage

Introduction

Among patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), 35–45% have intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) [1]. This is an important determinant of outcome after ICH [2]. IVH volume is a valuable tool to assess prognosis after ICH [3], but at present exact IVH volumes are labor-intensive to determine. A semi-quantitative bedside method, the modified Graeb Scale (mGS), has been developed to estimate the extent characteristics of the IVH without measuring exact IVH volumes [4, 5]. The mGS is based upon 3 factors: location of the IVH, the estimated blood volume in each ventricular compartment, and the presence of ventricle expansion due to hematoma (online suppl. table e-1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000442575). A more detailed description of the method has been published [4, 5].

The mGS has a high inter- and intraobserver reliability [5, 6] and correlates well with IVH volume [5]. Additionally, mGS predicts poor functional outcome after ICH with higher accuracy than the original Graeb Scale (oGS) [7] from which mGS is derived [5]. The oGS predicts poor functional outcome after IVH with similar precision as 2 other methods for IVH assessment [8–10]. The mGS has been validated in a cohort derived from clinical trials [5] and was associated with mortality in a convenience sample [11], but the relevance of these observations to broader ICH populations is unknown. To evaluate the external validity of mGS as a bedside tool for prognostication of outcome, we investigated in an unselected cohort of supratentorial ICH-patients whether mGS can (1) prognosticate 30-day survival; (2) prognosticate poor 90-day functional outcome; and (3) improve the precision of the outcome prognostication compared to only using data the on presence or absence of IVH.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Patient Inclusion

In the hospital-based Lund Stroke Register [12], we prospectively and consecutively registered all first-ever stroke patients admitted to Skåne University Hospital, Lund, Sweden, who were inhabitants of the local catchment area, where no other hospital is located (2001–2006: mean 240,000 inhabitants) [13], between March 2001 and February 2007. All Swedish citizens have universal access to health care, giving them access to their local hospital. ICH-patients were cared for according to local guidelines at the neurological stroke unit or the neurosurgical/neurological intensive care unit. Patients diagnosed with ICH only at autopsy or diagnosed and treated solely as outpatients were not registered. Data on the total Swedish population 2001–2006 in 10-year age spans were obtained from the National Census Office (statistics Sweden) [13]. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board.

Inclusion required the presence of spontaneous ICH or IVH detected on a baseline CT-scan performed within 7 days of clinical stroke onset. Patients with ICH secondary to trauma, vascular malformation, arterial aneurysm, tumor, or infarct were excluded. We chose the 7-day time limit in order to reduce the risk of underestimating radiological imaging-characteristics, as these characteristics change over time after stroke onset due to hemoglobin breakdown [14].

The prognostic factors and indications for surgical therapy differ between infratentorial and supratentorial ICH [15] and we therefore excluded infratentorial ICH-patients from further analysis.

Assessment of Radiological Characteristics

CT-scans were used to determine ICH volume (using the AxBxC/2-method) [16], ICH location (deep, lobar, cerebellar, brainstem, or mixed deep and lobar), and mGS. Two independent readers (B.M.H. and T.C.M.) were blinded from patient history when determining radiological characteristics. An initial training series of 23 CT-scans (15 with supratentorial ICH and IVH) was co-assessed by the 2 readers. Assessment differences between observers were resolved during a meeting to form a consensus decision. The mean mGS score between readers was used in statistical analysis if the score was not arrived at by consensus. This resulted in some mGS scores not being integer values. Neuroradiological expertise (PCS) was consulted when specific neuroradiological questions arose.

Clinical Characteristics

Baseline clinical characteristics were gathered directly from patient interviews and/or from medical records. The level of consciousness at admission according to the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) [17] was estimated from medical records. If GCS could not be assessed, a translation from baseline Reaction Level Scale score (the routine method for assessing level of consciousness in Sweden) was used [18]. The following cardiovascular risk factors were registered: diabetes mellitus, smoking at baseline, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, atrial fibrillation and/or ischemic heart disease present at baseline or in patient history [19]. Anticoagulant and/or antiplatelet therapy within 2 days before ICH onset was recorded as well as previous transient ischemic attack, classified as focal neurological symptoms lasting less than 24 h. Surgical treatment was defined as ICH-evacuation and/or insertion of an external ventricular drain (EVD) for acute lowering of intracranial pressure.

Laboratory Characteristics

WBC count and C-reactive protein (CRP) at admission to hospital were included as general markers for inflammation and systemic stress reaction [20, 21] ; they were dichotomized at the local laboratory’s upper reference limit >11 × 109/l, and >5 mg/l, respectively.

Follow-Up

We obtained survival status for all patients in February 2011 from the National Census Office by using specific personal identification numbers assigned to all Swedish citizens. Follow-up data on functional outcome were either prospectively obtained from the Swedish Stroke Register (Riks-Stroke) – a national quality register for acute stroke, or retrospectively from medical records [22]. Functional outcome at 90-days after ICH onset (using the time point closest to 90 days within the range 50–150 days, or death within 150 days) was assessed using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) [23]. Riks-Stroke’s 90-day follow-up includes 5 self-reported items on activities of daily life, which can be translated into mRS [24]. Poor functional outcome was defined as mRS ≥4. If no outcome was available in the 50–150 days post-ictus window, the outcome was treated as missing data.

Statistics

Descriptive analyses were done using Fishers exact test, Pearson’s χ2 test, and Mann–Whitney U test where appropriate. Inter-rater agreement for mGS assessment was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Incidence was age-adjusted to the Swedish population 2001–2006, 95% CIs were calculated by Poisson distribution. Two-sided p values <0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Logistic regression analyses were used for univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors for patients with supratentorial ICH with 30-day survival and poor functional outcome (as defined above) as dependent factors. Surgery was excluded in the regression analysis, as active intervention for a selected subgroup should be analyzed separately, which is beyond the scope of this study. Covariates with p values <0.10 were included in multivariate analyses. The mGS and the dichotomous indicator of IVH were included in 2 separate multivariate analyses (hereafter referred to as models A and B, respectively) as these variables are highly co-linear. Multiple imputation (MI) was used to mitigate potential bias and loss of power due to missing covariates and functional outcome assessments. Missing values were imputed using binary and ordinal logistic regression models including age and ICH volume, and results from 20 imputed datasets were combined using MI procedures. Kaplan–Meier curves and log rank test were used to study differences in 30-day survival between groups on mGS, divided into quartiles.

The DeLong test for paired receiver-operator characteristics (ROC) curves was used to compare area under (the ROC) curve (AUC) for logistic regression models with and without mGS, adjusted for age and ICH-volume, for patients with supratentorial ICH and concomitant IVH. Due to the limited sample size, model adjustment was limited to age and ICH volume to avoid potential bias and reduce variability of estimates. Non-nested models were compared using the Vuong test.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM-SPSS version 20 and R version 3.1.0. MI and ROC analyses were performed with R using mitools package [25] and the pROC package [26], respectively.

Results

Study Population

A total of 291 patients with ICH were identified. After exclusion of 30 patients with ICH due to secondary causes, the annual age-adjusted incidence, estimated from the 261 remaining recorded cases with spontaneous ICH, was 21.0/100,000 (95% CI 18.4–23.5). For the analysis of supratentorial ICH, we then excluded patients with baseline CT-scan performed ≥7 days after ictus (n = 7), missing baseline clinic-radiological characteristics due to initial hospitalization elsewhere (n = 8), and infratentorial ICH (n = 48, of which 28 had concomitant IVH). Supratentorial ICH was thus observed among 198 (80%) patients of whom 86 had IVH (median mGS 12; range 1–28).

Data on survival were available for all patients. The functional outcome, 90 days post ictus, could not be obtained for 17 (8.6%) of the included patients. For the 181 supratentorial ICH-patients in which functional outcome could be obtained, follow-up information came from Riks-Stroke and medical journals in 135 (75%) and 46 (25%) cases, respectively. Of 60 patients who survived 150 days after ICH onset and were subsequently followed up by Riks-Stroke, 44 patients (73%) completed the response forms themselves, 11 (18%) had caregiver or staff answering for them, and 5 (8%) had no information on who completed the form. Among patients surviving 150 days, functional outcome was assessed 103 days after ICH onset in mean (SD 20.0; median 94). Patients with supratentorial ICH who were comatose at admission (GCS <9; n = 41) had a 30-day mortality of 93%.

Among the 198 patients with supratentorial ICH baseline, CT was performed within 24 h in 151 (76%) and within 48 h in 186 (94%) of the patients. Fifteen supratentorial ICH-patients with IVH were part of the training series and therefore excluded from assessments of inter-rater agreement. A perfect agreement between readers was obtained in 20 (28%) of the 71 individual mGS assessments, and the readers scores were within ±3 points in 66 (93%) cases; this corresponds to a high inter-rater agreement (ICC 0.95 for single measures; 95% CI 0.92–0.97).

Comparisons between Supratentorial ICH-Patients with and without IVH

No statistically significant differences in gender or age distribution were observed between supratentorial ICH-patients with and without IVH (online suppl. table e-2). Compared with ICH-patients without ventricular blood, patients with concomitant IVH had lower GCS at admission (p < 0.001), larger ICH-volume (p < 0.001), higher rates of deep and lower rate of lobar ICH (p < 0.001), higher CRP (p = 0.001), higher WBC count (p < 0.001), and higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus (p = 0.005). Further information on baseline demographics, risk-factors, and functional outcome for supratentorial ICH-patients with and without IVH is shown in online supplementary table e-2.

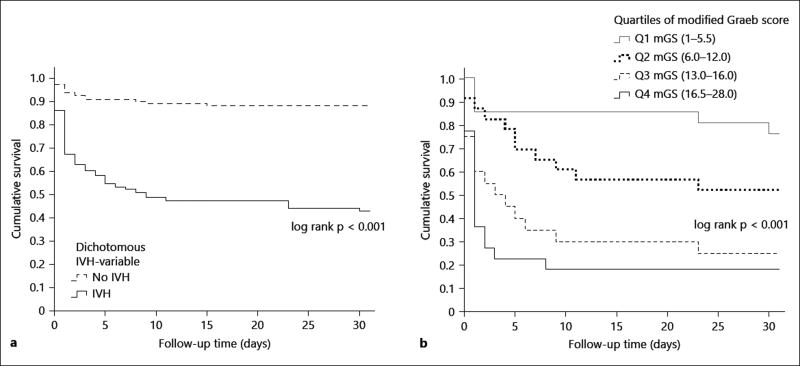

The 30-day and 1-year mortality rate, respectively, were 49 (57%; 95% CI 46–67%) and 58 (67%; 95% CI 57–77%) for patients with supratentorial ICH and IVH, compared to 13 (12%; 95% CI 6–17%) and 22 (20%; 95% CI 11–25%) for ICH-patients without IVH (p < 0.001, Pearson’s χ2 test). The differences in 30-day mortality between patients with and without IVH are illustrated in figure 1. Patients with supratentorial ICH and IVH at baseline, who survived 150 days post ictus, generally had worse functional outcome at follow-up than patients without IVH (p = 0.018; Mann–Whitney U test; distribution shown in online suppl. table e-2).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves illustrating survival after supratentorial ICH, patients stratified by presence of IVH and mGS quartiles. Survival truncated at 30-day after ICH. a All patients with supratentorial ICH (n = 198) divided into groups based on IVH yes/no. log rank test for overall comparison of groups, p < 0.001. b Patients with IVH (i.e. mGS >0; n = 86) divided into groups of mGS quartiles (Q1 = first quartile, mGS 1–5.5; Q2 = second quartile, mGS 6.0–12.0; Q3 = third quartile, mGS 13.0–16.0; Q4 = fourth quartile, mGS 16.5–28.0). Non-integral mGS values were obtained for quartiles as mean mGS-values were used. log rank test for overall comparison of groups, p < 0.001.

mGS vs. Dichotomized IVH Yes/No Regarding 30-Day Survival after Supratentorial ICH

As illustrated in figure 1, among patients with supratentorial ICH and IVH, higher mGS was associated with lower survival rates (p < 0.001 for overall comparison of mGS quartiles), where the first mGS quartile had a 30-day survival of 76%, while patients in mGS quartiles 3 and 4 had a notably worse 30-day survival (25 and 18%, respectively).

In univariate analyses, presented in table 1, higher mGS (per point increase; OR 1.22; 95% CI 1.15–1.28; p < 0.001), and presence of IVH (yes/no; OR 10.09; 95% CI 4.92–20.69; p < 0.001) were both associated with higher 30-day mortality after supratentorial ICH.

Table 1.

Univariate associations with 30-day mortality and poor functional outcome (mRS ≥4, including death) 90 days after supratentorial ICH, based on logistic regression with multiple imputation for missing covariates

| Variable | 30-day survival | Poor functional outcome (mRS ≥4) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Sex, female | 1.07 (0.59–1.97) | 0.815 | 1.16 (0.65–2.08) | 0.613 |

| Age (per year increased) | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | 0.001 | 1.06 (1.03–1.09) | <0.001 |

| IVH, yes/no | 10.09 (4.92–20.69) | <0.001 | 7.19 (3.56–14.5) | <0.001 |

| mGS (per point increase) | 1.22 (1.15–1.28) | <0.001 | 1.18 (1.10–1.25) | <0.001 |

| ICH volume (per ml increase) | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | <0.001 |

| GCS (per point increase) | 0.57 (0.49–0.67) | <0.001 | 0.59 (0.48–0.74) | <0.001 |

| Deep ICH | 1.60 (0.81–3.17) | 0.137 | 1.53 (0.82–2.85) | 0.183 |

| Hypertension | 0.94 (0.48–1.85) | 0.858 | 0.86 (0.46–1.62) | 0.647 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.08 (1.05–4.11) | 0.035 | 2.72 (1.35–5.51) | 0.005 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1.35 (0.60–3.03) | 0.468 | 1.20 (0.56–2.58) | 0.642 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3.22 (1.34–7.71) | 0.009 | 2.16 (0.85–5.55) | 0.108 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0.81 (0.41–1.59) | 0.536 | 0.78 (0.40–1.51) | 0.456 |

| Previous transient ischemic attack | 2.66 (1.06–6.67) | 0.038 | 2.20 (0.83–5.83) | 0.113 |

| Smoking | 0.92 (0.39–2.21) | 0.858 | 1.04 (0.47–2.30) | 0.918 |

| CRP >5, mg/l | 2.27 (1.22–4.25) | 0.010 | 1.74 (0.96–3.15) | 0.066 |

| WBC count >11.0 × 109/l | 4.16 (2.15–8.03) | <0.001 | 4.64 (2.18–9.86) | <0.001 |

| Anticoagulant therapy | 1.47 (0.60–3.60) | 0.398 | 1.63 (0.66–4.06) | 0.293 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 2.33 (1.20–4.55) | 0.013 | 2.03 (1.03–4.02) | 0.042 |

A more refined risk estimate was obtained in multivariate models with the mGS (per point increase; OR 1.16; 95% CI 1.06–1.27; p = 0.002) compared to the dichotomous IVH (yes/no; OR 4.87; 95% CI 1.35–17.48; p = 0.015) even though both remained as prognostic factors for 30-day survival after adjustment for possible confounders (online suppl. table e-3). In both multivariate models A and B, ICH-volume, GCS, and atrial fibrillation continued to be associated with 30-day mortality (p < 0.05 for all comparisons), while age was not (p > 0.05 in both models). See online supplementary table e-3 for corresponding estimates and 95% CIs.

mGS vs. Dichotomized IVH Yes/No Regarding Functional Outcome 90 Days after Supratentorial ICH

In univariate analyses, presence of IVH was associated with a 7-fold increase in odds of having poor functional outcome 90 days after ICH (OR 7.19; 95% CI 3.56–14.50; p < 0.001) and each point increase in mGS was associated with a 18% increase in the odds of poor outcome (OR 1.18; 95% CI 1.10–1.25; p < 0.001), as shown in table 1. These associations remained after adjusting for potential confounders in multivariate models A and B (online suppl. table e-3), again with mGS estimates being more elaborate (OR 1.11 per point estimate; 95% CI 1.02–1.20; p = 0.011) compared with the binary IVH (yes/no; OR 4.17; 95% CI 1.48–11.75; p = 0.007). In multivariate analysis model A (including mGS), age, ICH volume, and WBC count remained associated with poor outcome (p < 0.05; online suppl. table e-3 for magnitudes of effects), while in model B (IVH yes/no), the association with poor outcome remained for age, ICH-volume, and GCS.

ROC Analyses of mGS among Supratentorial ICH-Patients with IVH

In ROC analyses of all patients with supratentorial ICH and IVH, the inclusion of the mGS in the prognostic model for 30-day survival resulted in better model fit, as indicated by a significant reduction in model deviance (χ2 = 12.59; p < 0.001) and a trend toward higher AUC (0.886 vs. no mGS 0.812; p = 0.053). The addition of mGS increased sensitivity from 67 to 88% at a specificity of 80% as illustrated in online supplementary figure e-1A. In the prognostic model for poor functional outcome (online suppl. fig. e-1B), inclusion of the mGS did not result in a significant reduction in model deviance (χ2 = 1.56; p = 0.211) or increased AUC (0.83 vs. no mGS 0.82; p = 0.563).

Discussion

We found a great variability within the clinical courses of ICH-patients with IVH as illustrated by the large differences in cumulative survival in different mGS quartiles (fig. 1). The risk estimate (OR) obtained from mGS improved the possibility to stratify ICH patients with more detail compared with the more coarse risk estimate (OR) derived from the dichotomous variable IVH yes/no. These findings support the importance of routinely quantifying IVH to better determine prognosis after ICH.

The mGS was an independent predictor of 30-day survival after ICH in the multivariate analysis with a 16% increased odds for death per increased mGS point (OR 1.16; 95% CI 1.06–1.27). In survival tables depicting the distribution of survival for subgroups of IVH, large differences in survival were seen between patients in the first quartile and the third and fourth quartile of mGS, where the former group’s survival was similar to that of ICH-patients without IVH, and the latter had a notably worse survival compared to all IVH-patients.

In our study, each point increase in mGS increased the odds for a poor 90-day functional outcome (mRS ≥4) by 11% (OR 1.11; 95% CI 1.02–1.20), which is in line with the 12% previously reported (OR 1.12; 95% CI 1.05–1.19) [5].

The mGS ROC analyses showed a trend toward improving the accuracy of survival prognostication (AUC including mGS 0.886 vs. no mGS 0.812; p = 0.053) among IVH-patients, although this finding did not reach statistical significance. Models using AUC may underestimate the impact of new prognostic markers when adjusted for other strong predictors that on their own render a high sensitivity and specificity [27]. Given the limited sample and that we adjusted for 2 of the most potent predictors of outcome after ICH (age and ICH-volume), the trend toward increased AUC by adding mGS suggests that mGS is an important prognostic marker for survival after ICH. Considering the high prognostic accuracy of the original models without mGS (AUC 0.812 and 0.82 for survival and poor functional outcome), this study risked being underpowered to show an increased accuracy by the addition of mGS when analyzed by c-statistics (ROC). With this in mind, we base our conclusions on the usefulness of mGS for prognostication on the multiple regression analysis and survival tables rather than ROC curves.

Other factors independently predicting survival and poor outcome alongside mGS were the previously well-established markers for ICH severity [2], ICH-volume and GCS. Among these, mGS (as a surrogate for IVH severity/ extent) and ICH-volume are potentially available for direct treatment. GCS is not available for specific treatment but can instead be considered an early outcome variable depending on other factors. The presence of a strong association between mortality and one variable (e.g. GCS) in a subgroup of patients is likely to obscure additional effects on outcome of other factors, like mGS. With this in mind, it is notable that mGS continued to be associated with both mortality and poor functional outcome even after adjustment for GCS in multivariate analyses.

The high ascertainment rate for stroke in general and ICH in particular – due to high hospital admission rates [12, 28, 29] and CT rates [12, 30] in this population, lends validity as well as generalizability to our findings. Additionally, the personal identification numbers enabled survival follow-up from official sources for all included patients. Our study’s incidence rate of 21.0 (95% CI 18.4–23.5) per 100,000 person-years is in line with previous international estimates of ICH (24.6; 95% CI 19.7–30.7) [31] but slightly lower than a prior Southern Swedish study from 1996 (28.4, no CI available for age standardized incidence) [32] a difference that might be due to the inclusion of patients with previous stroke and patients diagnosed with ICH at autopsy in that study. The presence of universal access to health care at one single hospital for our population decreases the importance of many social and economic factors from influencing the outcomes of ICH and increases the relevance of these findings as an estimate of outcome in populations with uniform access to high levels of care. The low surgery rate in our study (8%, ICH evacuation and/or EVD placement) is similar to North American practice [33]. One main limitation of this study is that functional outcome was assessed by telephone or from medical records and not from a clinical examination, making an objective assessment more difficult. Furthermore, we lacked information on hematoma expansion and ‘do not resuscitate’ decisions, which are factors known to affect the prognosis after ICH [34, 35]. We restricted our analysis to supratentorial ICH, which likely increases the models prognostic accuracy at the cost of limited generalizability of results for infratentorial ICH.

As patients with IVH have a greatly increased risk of death and poor functional outcome, estimations of IVH severity are central in order to better understand the disease, to develop better therapies, and to implement delivery of new therapies in clinical practice. The mGS seems to be an easy and quick way to estimate IVH severity, but the results of this study need to be validated in epidemiological cohorts elsewhere as it lacks external validation. Likewise, there is a need to assess if mGS can be incorporated into established ICH prognostic scales similar to how the oGS has been incorporated into the Hemphill ICH-score by Godoy et al. [36]. However, to provide useful data for design of clinical trials, such a comparison likely needs to be adjusted for thresholds of established prognostic factors, supratentorial vs. infratentorial ICH-location, and GCS subgroups. The effect of IVH severity on functional recovery after ICH alongside other radiological factors, such as for instance, white matter lesions [37], also needs to be evaluated.

Conclusions

The mGS improves survival and functional outcome prediction after supratentorial ICH beyond other established prognostic factors in a broad ICH population. The mGS makes it possible to differentiate between severe and less severe IVH, which is of importance, as survival after ICH differs greatly with IVH severity. To our knowledge, mGS is the first scale for IVH severity assessment that has been validated in ICH patients from both clinical trials and a consecutive hospital-based study, indicating the usefulness of mGS for both research and bedside situations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Study Funding

A. Lindgren is supported by: Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, Region Skåne, Skåne University Hospital, the Freemasons Lodge of Instruction EOS in Lund, King Gustaf V and Queen Victoria’s, Foundation, Lund University, and the Swedish Stroke Association.

D.F. Hanley is supported by: the NINDS grant R01NS046309 for the MISTIE II trial, the NINDS grant U01NS062851 for the CLEAR III trial, the NINDS grant U01NS080824 for the MISTIE III trial, grant 272 for Eleanor Dana Charitable Trust, and the Jeffry and Harriet Legum Endowment.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

B.M. Hansen, T.C. Morgan, J.F. Betz, P.C. Sundgren, B. Norrving, D.F. Hanley, and A. Lindgren report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hanley DF. Intraventricular hemorrhage: severity factor and treatment target in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:1533–1538. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.535419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemphill JC, 3rd, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32:891–897. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuhrim S, Horowitz DR, Sacher M, Godbold JH. Volume of ventricular blood is an important determinant of outcome in supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:617–621. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199903000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinson HE, Hanley DF, Ziai WC. Management of intraventricular hemorrhage. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2010;10:73–82. doi: 10.1007/s11910-010-0086-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan TC, Dawson J, Spengler D, Lees KR, Aldrich C, Mishra NK, Lane K, Quinn TJ, Diener-West M, Weir CJ, Higgins P, Rafferty M, Kinsley K, Ziai W, Awad I, Walters MR, Hanley D CLEAR and VISTA Investigators. The modified Graeb score: an enhanced tool for intraventricular hemorrhage measurement and prediction of functional outcome. Stroke. 2013;44:635–641. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.670653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnan K, Mukhtar SF, Lingard J, Houlton A, Walker E, Jones T, Sprigg N, Cala LA, Becker JL, Dineen RA, Koumellis P, Adami A, Casado AM, Bath PM, Wardlaw JM. Performance characteristics of methods for quantifying spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage: data from the Efficacy of Nitric Oxide in Stroke (ENOS) trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:1258–1266. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-309845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graeb DA, Robertson WD, Lapointe JS, Nugent RA, Harrison PB. Computed tomographic diagnosis of intraventricular hemorrhage. Etiology and prognosis. Radiology. 1982;143:91–96. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.6977795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallevi H, Dar NS, Barreto AD, Morales MM, Martin-Schild S, Abraham AT, Walker KC, Gonzales NR, Illoh K, Grotta JC, Savitz SI. The IVH score: a novel tool for estimating intraventricular hemorrhage volume: clinical and research implications. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:969–974.e1. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318198683a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang BY, Bruce SS, Appelboom G, Piazza MA, Carpenter AM, Gigante PR, Kellner CP, Ducruet AF, Kellner MA, Deb-Sen R, Vaughan KA, Meyers PM, Connolly ES., Jr Evaluation of intraventricular hemorrhage assessment methods for predicting outcome following intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2012;116:185–192. doi: 10.3171/2011.9.JNS10850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LeRoux PD, Haglund MM, Newell DW, Grady MS, Winn HR. Intraventricular hemorrhage in blunt head trauma: an analysis of 43 cases. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:678–684. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199210000-00010. discussion 684–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mustanoja S, Satopää J, Meretoja A, Putaala J, Strbian D, Curtze S, Haapaniemi E, Sairanen T, Niemelä M, Kaste M, Tatlisumak T. Extent of secondary intraventricular hemorrhage is an independent predictor of outcomes in intracerebral hemorrhage: data from the Helsinki ICH Study. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:576–581. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallstrom B, Jonsson AC, Nerbrand C, Petersen B, Norrving B, Lindgren A. Lund Stroke Register: hospitalization pattern and yield of different screening methods for first-ever stroke. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;115:49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Statistics Sweden: Official Swedish Population Statistics. [retrieved August 25, 2014]; http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101A/BefolkningNy/?rxid = 91a471aa-6d47–4e8e-a9b3–50c6a1833abb.

- 14.Kidwell CS, Wintermark M. Imaging of intracranial haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:256–267. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qureshi AI, Mendelow AD, Hanley DF. Intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet. 2009;373:1632–1644. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60371-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broderick JP, Brott TG, Duldner JE, Tomsick T, Huster G. Volume of intracerebral hemorrhage. A powerful and easy-to-use predictor of 30-day mortality. Stroke. 1993;24:987–993. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.7.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teasdale G, Murray G, Parker L, Jennett B. Adding up the Glasgow Coma Score. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1979;28:13–16. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-4088-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walther SM, Jonasson U, Gill H. Comparison of the Glasgow Coma Scale and the Reaction Level Scale for assessment of cerebral responsiveness in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:933–938. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1757-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Starby H, Delavaran H, Andsberg G, Lovkvist H, Norrving B, Lindgren A. Multiplicity of risk factors in ischemic stroke patients: relations to age, sex, and subtype – a study of 2,505 patients from the lund stroke register. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;42:161–168. doi: 10.1159/000357150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castellanos M, Leira R, Tejada J, Gil-Peralta A, Davalos A, Castillo J Stroke Project, Cerebrovascular Diseases Group of the Spanish Neurological Society. Predictors of good outcome in medium to large spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral haemorrhages. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:691–695. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.044347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki S, Kelley RE, Dandapani BK, Reyes-Iglesias Y, Dietrich WD, Duncan RC. Acute leukocyte and temperature response in hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1995;26:1020–1023. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asplund K, Hulter Åsberg K, Appelros P, Bjarne D, Eriksson M, Johansson A, Jonsson F, Norrving B, Stegmayr B, Terént A, Wallin S, Wester PO. The Riks-Stroke story: building a sustainable national register for quality assessment of stroke care. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:99–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJ, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1988;19:604–607. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.5.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eriksson M, Appelros P, Norrving B, Terent A, Stegmayr B. Assessment of functional outcome in a national quality register for acute stroke: can simple self-reported items be transformed into the modified rankin scale? Stroke. 2007;38:1384–1386. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000260102.97954.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lumley T. Tools for Multiple Imputation of Missing Data. [accessed December 10, 2014];R package version 2.2. 2012 http://cran.r-project.org/src/contrib/Archive/mitools/

- 26.Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez JC, Müller M. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook NR. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation. 2007;115:928–935. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.672402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Appelros P, Högerås N, Terént A. Case ascertainment in stroke studies: the risk of selection bias. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;107:145–149. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.02120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pessah-Rasmussen H, Engstrom G, Jerntorp I, Janzon L. Increasing stroke incidence and decreasing case fatality, 1989–1998: a study from the stroke register in Malmo, Sweden. Stroke. 2003;34:913–918. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000063365.10841.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stegmayr B, Asplund K, Hulter-Asberg K, Norrving B, Peltonen M, Terent A, Wester PO. Stroke units in their natural habitat: can results of randomized trials be reproduced in routine clinical practice? Riks-Stroke Collaboration. Stroke. 1999;30:709–714. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, van der Tweel I, Algra A, Klijn CJ. Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:167–176. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nilsson OG, Lindgren A, Stahl N, Brandt L, Saveland H. Incidence of intracerebral and subarachnoid haemorrhage in southern Sweden. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:601–607. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andaluz N, Zuccarello M. Recent trends in the treatment of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: analysis of a nationwide inpatient database. J Neurosurg. 2009;110:403–410. doi: 10.3171/2008.5.17559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis SM, Broderick J, Hennerici M, Brun NC, Diringer MN, Mayer SA, Begtrup K, Steiner T Recombinant Activated Factor VII Intracerebral Hemorrhage Trial Investigators. Hematoma growth is a determinant of mortality and poor outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2006;66:1175–1181. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000208408.98482.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hemphill JC, 3rd, Newman J, Zhao S, Johnston SC. Hospital usage of early do-not-resuscitate orders and outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2004;35:1130–1134. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000125858.71051.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Godoy DA, Piñero G, Di Napoli M. Predicting mortality in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: can modification to original score improve the prediction? Stroke. 2006;37:1038–1044. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000206441.79646.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee SH, Kim BJ, Ryu WS, Kim CK, Kim N, Park BJ, Yoon BW. White matter lesions and poor outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage: a nationwide cohort study. Neurology. 2010;74:1502–1510. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dd425a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.