Abstract

Importance

A blood test to determine whether to treat patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) with an androgen receptor signaling (ARS) inhibitor or taxane is an unmet medical need.

Objective

To determine whether a validated assay for the nuclear-localized androgen receptor splice variant 7 (AR-V7) protein in circulating tumor cells can determine differential overall survival among patients with mCRPC treated with taxanes vs ARS inhibitors.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This blinded correlative study conducted from December 31, 2012, to September 1, 2016, included 142 patients with histologically confirmed mCRPC and who were treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, The Royal Marsden, or the London Health Sciences Centre. Blood samples were obtained prior to administration of ARS inhibitors or taxanes as a second-line or greater systemic therapy for progressing mCRPC.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Overall survival after treatment with an ARS inhibitor or taxane in relation to pretherapy AR-V7 status.

Results

Among the 142 patients in the study (mean [SD] age, 69.5 [9.6] years), 70 were designated as high risk by conventional prognostic factors. In this high-risk group, patients positive for AR-V7 who were treated with taxanes had superior overall survival relative to those treated with ARS inhibitors (median overall survival, 14.3 vs 7.3 months; hazard ratio, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.28-1.39; P = .25). Patients negative for AR-V7 who were treated with ARS inhibitors had superior overall survival relative to those treated with taxanes (median overall survival, 19.8 vs 12.8 months; hazard ratio, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.00-2.81; P = .05).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study suggests that nuclear-localized AR-V7 protein in circulating tumor cells can identify patients who may live longer with taxane chemotherapy vs ARS inhibitor treatment.

This cohort study examines whether an assay for the nuclear-localized androgen receptor splice variant 7 protein in circulating tumor cells can be used to estimate overall survival among patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with taxanes vs androgen receptor signaling inhibitors.

Key Points

Question

Is nuclear-localized androgen receptor splice variant 7 (AR-V7) protein in circulating tumor cells a treatment-selection marker for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer?

Findings

In this multi-institutional cohort study, 142 patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with either taxanes or androgen receptor signaling (ARS) inhibitors were observed for up to 4.3 years. Pretherapy circulating tumor cell status and treatment type were associated with overall survival; patients with AR-V7–positive circulating tumor cells had superior overall survival with taxanes vs ARS inhibitors, whereas patients with AR-V7–negative circulating tumor cells had superior overall survival with ARS inhibitors vs taxanes.

Meaning

The validated nuclear-localized AR-V7 assay can be used to select a taxane or ARS inhibitor and provide individual patient benefit.

Introduction

Androgen receptor signaling (ARS) inhibitors, such as abiraterone acetate and enzalutamide, and taxanes, such as docetaxel and cabazitaxel, are the most widely used drug classes of the US Food and Drug Administration–approved systemic therapies for progressing metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Prospective randomized clinical trial data comparing these drugs directly are lacking, but based on individual trial data, comparative safety profiles, and mode of administration (oral vs intravenous), ARS inhibitors are the preferred choice of treatment at the first-line decision point in the management of mCRPC.1 However, because response or failure to 1 ARS inhibitor does not uniformly guarantee response or nonresponse to a second ARS inhibitor,2,3,4 there are no formal guidelines on how best to sequence these agents to optimize individual patient outcomes.5 In routine clinical practice, the majority of patients with mCRPC receive a second ARS inhibitor after first-line ARS inhibition fails, despite the low prostate-specific antigen (PSA) response rate.6 In contrast, those who receive chemotherapy as the second-line treatment after progression on first-line treatment with an ARS inhibitor have, on average, a high initial PSA response rate. To date, however, no difference in overall survival (OS) between these groups has been demonstrated.6 A test that can better inform the choice of therapy in the second-line or greater setting is a critical unmet need in patient management.

Several diverse resistance mechanisms to ARS inhibitors have been identified through molecular profiling, many of which have been further elucidated to varying degrees in preclinical model systems. They include, but are not limited to, alterations in secondary signaling pathways and changes in the androgen receptor itself, such as amplification, mutations, and splice variants with truncations in the ligand-binding domain,7,8,9,10 of which androgen receptor splice variant 7 (AR-V7) is the most widely studied. Androgen receptor splice variant 7 is an alternatively spliced isoform of the AR gene (OMIM: 313700) that contains the DNA-binding domain but lacks the regulatory ligand-binding domain, leading to constitutive activation of oncogenic signaling and cell proliferation.11,12

The association between the detection of AR-V7 messenger RNA (mRNA) in an enriched (selected) fraction of circulating tumor cells (CTCs), poor PSA responses, and shorter radiographic progression-free survival times after treatment with ARS inhibitors was first reported in 2014.13 Follow-up studies with the same assay showed not only a negative association with OS for patients positive for AR-V7 who were treated with ARS inhibitors14 but also that PSA response and survival with taxane-based therapy were independent of AR-V7 status.15 Taken together, the results suggested that AR-V7 status could be used to guide the choice of treatment for men with progressive mCRPC in need of a change in therapy. A series of reports followed, using a range of AR-V7 assays in smaller cohorts, some refuting16 and others confirming the results,17 albeit to variable degrees, but, to our knowledge, none used OS as the primary outcome measure. Missing from several reports were the details of the analytical performance of the assay itself, and, in particular, the demonstration that the assay was fit for the purpose of using the reported result to support a clinical validation effort.18 For the assays that had achieved the level of performance for clinical validation, there lacked a clear demonstration of clinical utility as a biomarker indicating that outcomes would be improved by use of the test result to inform the treatment decision relative to nonuse of the test.19 Line of therapy was also rarely considered.

Use of the mRNA determinant as a blood-based biomarker has limitations such as stability of the blood sample, which varies as a function of the collection tube used and the time to sample processing, and in the case of a transcription factor such as AR-V7, an inability to discern if the coded protein is actually localized in the nucleus of cells where it functions to drive tumor growth. To address these considerations, we developed a protein-based assay to discern the presence and cellular localization of the AR-V7 protein in CTCs. We used the Epic Sciences platform, a non–selection-based approach that deposits all nucleated cells from a patient’s blood sample onto pathologic test slides and uses fluorescent scanners to image each cell and identify CTCs. The approach enables a higher sensitivity of CTC detection than the only assay that is cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration, CellSearch (Menarini Silicon Biosystems),20,21 as well as protein biomarker assessment on individual CTCs.20,21,22 In another report, the “training cohort,” 191 patients’ blood samples were evaluated prior to initiation of either ARS inhibition or taxane therapy; higher PSA response rates, longer radiographic progression-free survival times, and better OS were observed among patients with detectable nuclear-localized AR-V7–positive CTCs who received taxanes, relative to those who received ARS inhibitors.22

We report herein the validation of our findings in a separate, independent, multicenter cohort in which the criteria for a positive test result and the predicted outcome were prespecified, the clinical sites were blinded to the biomarker result, and the processing laboratory was blinded to patient outcomes. Two patient populations were evaluated: those for whom a choice of therapy between ARS inhibitors and taxanes was required after first-line treatment for mCRPC failed (second line or greater), and those in the first line who most often received ARS inhibition. This study reports on the patients receiving second-line treatment to determine if an assay for the nuclear-localized AR-V7 protein in CTCs can be used to determine treatment for mCRPC.

Methods

Patient Population

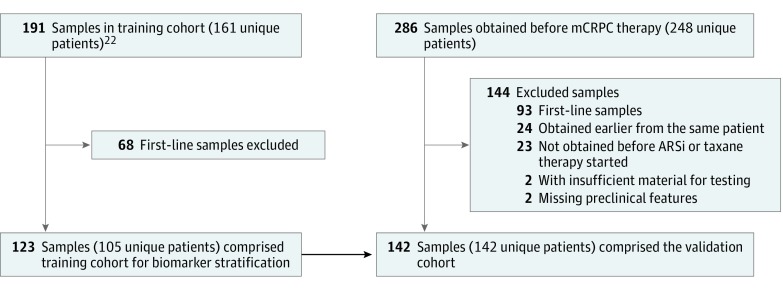

Between December 31, 2012, and September 1, 2016, 286 blood samples from 248 patients with histologically confirmed mCRPC who were undergoing a change in systemic therapy for progressive disease were obtained at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, New York), The Royal Marsden (London, England), and London Health Sciences Centre (London, Ontario, Canada). A total of 144 samples were excluded from analysis: 93 were obtained prior to administration of first-line therapy for mCRPC, 24 were duplicate samples from the same patient, 23 were obtained prior to a drug that was not an ARS inhibitor or taxane, 2 had insufficient material for testing, and 2 had missing requisite preclinical measures (Figure 1). The remaining 142 blood samples (70 before initiation of therapy with an ARS inhibitor; 72 before initiation of therapy with a taxane) were used for the utility analysis in the second-line or greater therapy setting. The institutional review boards of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, The Royal Marsden, and London Health Sciences Centre approved this study. All patients provided written informed consent.

Figure 1. Distribution of Patient Samples in the Training Cohort and Validation Cohort.

CONSORT diagram showing the breakdown and relationship of blood samples analyzed in the previous training cohort and for this validation study. Second-line and greater line samples from a study by Scher et al22 were analyzed as the training cohort, from which the risk stratification method was developed for this validation study. AR-V7 indicates androgen receptor splice variant 7; ARSi, androgen receptor signaling inhibitors; and mCRPC, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

All patients underwent a history taking that included details of stage at diagnosis, initial management and all subsequent systemic therapies, a physical examination, and laboratory studies including complete blood count, chemistry panel (albumin, alkaline phosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase, PSA, and hemoglobin levels), and serum testosterone levels to confirm castration status (<50 ng/dL [to convert to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 0.0347]). Documentation of disease progression required a minimum of 2 increasing PSA levels tested 1 or more weeks apart, new lesions as determined by bone scintigraphy, and/or new or enlarging soft-tissue lesions as determined by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, per Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 3 guidelines.23 Blood samples were obtained prior to initiation of either ARS inhibition or taxane therapy. The choice of therapy was at the discretion of the treating physician without knowledge of CTC count or AR-V7 status. The Table summarizes the characteristics of patients at the time the blood sample was obtained.

Table. Patient Sample Characteristics of Therapy Outcome Comparison Cohorta.

| Characteristic | Training Cohort | Validation Cohort | Pre–ARS Inhibitors | Pre-Taxane | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | |||||

| Unique patients, No. | 105 | 142 | NA | NA | NA |

| Death events, No. (%) | 91 (86.7) | 85 (59.9) | NA | NA | NA |

| Clinical site, No. (%) | MSK, 105 (100) | ICR, 25 (17.6); LHS, 5 (3.5); MSK, 112 (78.9) | NA | NA | NA |

| Primary therapy, No. (%) | |||||

| Prostatectomy | 50 (47.6) | 55 (38.7) | NA | NA | NA |

| Radiotherapy | 17 (16.2) | 24 (16.9) | NA | NA | NA |

| Brachytherapy | 6 (5.7) | 6 (4.2) | NA | NA | NA |

| None | 32 (30.5) | 56 (39.4) | NA | NA | NA |

| Samples | |||||

| Total, No. | 123 | 142 | 70 | 72 | .31 |

| Second-line treatment, No. (%) | 50 (40.7) | 52 (36.6) | 37 (52.9) | 15 (20.8) | <.001 |

| Third-line treatment, No. (%) | 31 (25.2) | 45 (31.7) | 19 (27.1) | 26 (36.1) | |

| Fourth-line or greater, No. (%) | 42 (34.1) | 45 (31.7) | 14 (20.0) | 31 (43.1) | |

| Median survival, mo | 13.5 | 13.2 | 16.0 | 12.9 | .18 |

| Pretherapy clinical measures available to physician | |||||

| Age, median (range), y | 69 (48-91) | 70 (40-91) | 70.5 (40-91) | 70 (48-85) | .31 |

| Albumin, median (range), g/dL | 4.2 (3.1-4.9) | 4 (2.4-4.7) | 4 (2.4-4.7) | 4 (2.9-4.6) | .14 |

| Hemoglobin, median (range), g/dL | 11.7 (7.0-15.0) | 11.7 (7.1-14.8) | 11.9 (7.1-14.8) | 11.45 (8.0-14.8) | .32 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, median (range), U/L | 237 (123-1004) | 229.5 (101-1487) | 203 (101-1231) | 245 (152-1487) | .002 |

| PSA, median (range), ng/mL | 59.4 (0.009-3728.2) | 68.3 (0.05-16275) | 30.3 (0.05-1412) | 122 (3.9-16275) | <.001 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, median (range), U/L | 123 (42-1816) | 112 (44-1055) | 91.5 (44-1040) | 127 (49-1055) | .006 |

| Presence of liver and/or lung metastases, No. (%) | 19/123 (15.4) | 37/142 (26.1) | 14/70 (20.0) | 23/72 (31.9) | .17 |

| Pretherapy clinical measures unavailable to physician | |||||

| AR-V7 positivity, No. (%) | 31/123 (25.2) | 34/142 (23.9) | 14/70 (20.0) | 22/72 (30.6) | .18 |

Abbreviations: AR-V7, androgen receptor splice variant 7; ARS, androgen receptor signaling; ICR, The Royal Marsden Institute of Cancer Research; LHS, London Health Sciences; MSK, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; NA, not available; PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

SI conversion factors: To convert albumin to grams per liter, multiply by 10.0; to convert hemoglobin to grams per liter, multiply by 10.0; to convert lactate dehydrogenase to microkatals per liter, multiply by 0.0167; to convert PSA to micrograms per liter, multiply by 1.0; and to convert alkaline phosphatase to microkatals per liter, multiply by 0.0167.

All patients receiving second-line or greater therapy.

CTC Collection

A blood sample (10 mL) from each participant was collected in Streck tubes and processed within 48 hours. Red blood cells were lysed, and approximately 3 million nucleated blood cells were dispensed onto 10 to 16 glass microscope slides and placed at –80°C for long-term storage as previously described.22,24,25 Processing and testing of the blood samples were conducted in laboratories certified under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments regulations.

CTC Immunofluorescent Staining and Analysis

Identification, characterization, and analysis of CTCs have been described previously.22,24,25 In brief, slides created from blood samples from patients with mCRPC underwent automated immunofluorescent staining for DNA, cytokeratins, CD45, and AR-V7. A rabbit monoclonal anti–AR-V7 antibody (EPR15656; Abcam) was used for all applications described herein. Fluorescent scanners and morphologic algorithms were used for identification of CTCs, evaluating 2 slides per blood sample. Clinical laboratory scientists licensed in California conducted the final quality control of CTC classification and subcellular biomarker localization.

Scoring criteria for AR-V7 were used as reported previously.22,25 In short, blood samples with at least 1 CTC with an intact nucleus and nuclear-localized AR-V7 signal to noise ratio above a previously established and validated background intensity per 2 slides tested ( ~ 1 mL of blood) were scored as AR-V7 positive. Blood samples without AR-V7–positive CTCs, or with no CTCs detected, were scored as AR-V7 negative. The analytical specificity of detection in contrived CTC blood samples, patient CTC blood samples, and healthy and malignant solid tissues and blood was previously reported.22

Statistical Analysis

The demographic characteristics of the patients and the clinical characteristics of the blood samples at the time blood was obtained were evaluated by use of descriptive statistics, overall and by the drug administered. The Wilcoxon rank sum test and the Fisher exact test were used to compare the clinical characteristics between treatment groups. The probability of survival over time was assessed using a Kaplan-Meier estimation. A proportional hazards model including treatment, AR-V7 status, and a treatment by AR-V7 status interaction was used to gauge treatment efficacy (ARS inhibitors vs taxanes) with respect to survival.

To investigate confounding factors that might influence the decision to administer an ARS inhibitor or taxane, a risk score was developed based on a prognostic model developed from our training cohort22 and applied to the current cohort (Table and the eFigure in the Supplement). A Cox proportional hazards regression model with risk score classification, treatment, AR-V7 status, each 2-way interaction, and the 3-way interaction, was then computed to evaluate AR-V7 as a biomarker that could indicate treatment within a risk group. All statistical analyses used R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), packages survival, sm, gee, ggplot2, and survminer. P < .05 (2-sided) was considered significant.

Results

Clinical Characteristics of the Patient Population

Treatment selection was determined by the treating physician. Patients were not assigned randomly to either ARS inhibitors or taxanes, necessitating the evaluation of potential imbalances in objective measures of disease severity (Table). Of the 142 blood samples, 70 were obtained prior to initiating treatment with an ARS inhibitor, and 72 were obtained prior to initiating treatment with a taxane. Overall, there was greater use of ARS inhibitors as a second-line treatment and more use of taxanes in the later lines of therapy (proportion receiving taxanes as second-line treatment, 0.30; proportion receiving taxanes as third-line or greater treatment, 0.64; P < .001). The observed median survival time was higher for patients receiving ARS inhibitors than for patients receiving taxanes (16.0 vs 12.9 months), but no significant difference was detected in the survival rates (P = .18). Looking at other factors that might have influenced treatment choice, we were unable to discern a difference between treatments based on median age (ARS inhibitors, 70.5 years; taxanes, 70.0 years; P = .31), albumin levels (ARS inhibitors, 4.0 g/dL; taxanes, 4.1 g/dL; P = .14), hemoglobin levels (ARS inhibitors, 11.9 g/dL; taxanes, 11.5 g/dL; P = .32), or the presence of lung and/or liver metastases before therapy (proportion receiving ARS inhibitors, 0.2; proportion receiving taxanes, 0.3 years; P = .18). However, patients receiving taxanes vs ARS inhibitors did have higher lactate dehydrogenase levels (245.0 vs 203.0 U/L; P < .001), PSA levels (133.4 vs 30.3 ng/mL; P < .001), and alkaline phosphatase levels (126.5 vs 9.5 U/L; P = .01). Rates of AR-V7 positivity were consistent between the training cohort (31 of 123 [25.2%]) and the validation cohort (34 of 142 [23.9%]) reported here.22

AR-V7 Status and Use of Taxanes and ARS Inhibitors

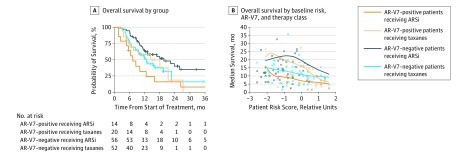

Overall survival based on treatment and AR-V7 status is presented in Figure 2. Patients treated with ARS inhibition had the most favorable survival outcome if they were AR-V7 negative and had the least favorable survival outcome if they were AR-V7 positive. The median survival of patients negative for AR-V7 was 19.8 months for those treated with an ARS inhibitor and 12.8 months for those treated with a taxane (hazard ratio, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.00-2.81; P = .05) (Figure 2A). In contrast, for patients with AR-V7–positive CTCs, those receiving taxanes had longer observed median survival times relative to those treated with ARS inhibitors (14.3 vs 7.3 months; hazard ratio, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.28-1.39; P = .25) (Figure 2A). That the observed difference was not statistically significant may have been attributable to the small sample size.

Figure 2. Association Between Patient Risk, Androgen Receptor Splice Variant 7 (AR-V7) Status, and Therapy.

A, Overall survival is shown for all 4 treatment-biomarker result groups using the Kaplan-Meier method not stratified by overall patient risk. B, Smoothed median estimates of overall survival as a function of patient risk and the 4 treatment-biomarker groups are shown. Censored patients are indicated by “o,” and deceased patients are indicated by “x.” Six observations (beyond 36 months) are attenuated by the graph axes. ARSi indicates androgen receptor signaling inhibitors.

Owing to the observational nature of the study, a patient-specific risk score, developed from the training cohort, was incorporated into the analysis. The coefficients in the model used to determine the patient risk scores are shown in the eFigure in the Supplement. The estimated median survival as a function of treatment, AR-V7 status, and risk score is depicted in Figure 2B. There is greater balance in patient numbers between the 4 groups when the risk scores are higher, and there are few patients with low risk scores who are positive for AR-V7. However, for patients with higher risk scores, there are sufficient patient numbers in all treatment and AR-V7 groups for between-group comparisons.

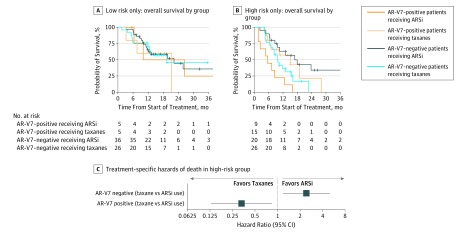

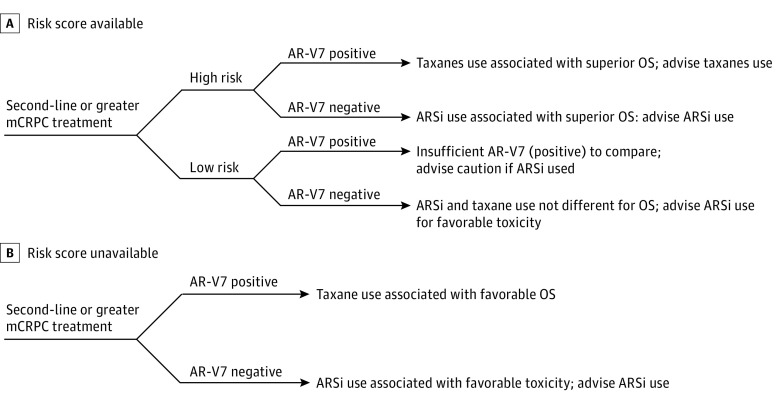

To address the low frequency of samples from patients with low-risk scores who are positive for AR-V7, patient classification as either low risk or high risk was integrated into the analysis. The classification was determined by dividing the risk scores from the training cohort data in half.22 The median risk score from the training cohort was –0.632. The results showed that, for the subset of patients classified as low risk within this data set, there were not enough patients positive for AR-V7 to evaluate differences in the survival rates between treatments stratified by biomarker result (Figure 3A). In contrast, the Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival based on treatment and AR-V7 status among high-risk patients provide a more discriminating picture (Figure 3B). Here, the Cox proportional hazards regression model showed that, for the high-risk patients negative for AR-V7, those treated with ARS inhibitors had a longer median OS than those treated with taxanes (16.9 vs 9.7 months; hazard ratio, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.12-5.06; P = .02), and for the high-risk patients positive for AR-V7, those receiving ARS inhibitors had a shorter median OS than those receiving taxanes (5.6 vs 14.3 months; hazard ratio, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.14-0.88; P = .03). Thus, for patients classified as high risk by existing clinical biomarkers, a qualitative interaction exists, providing evidence of the treatment choice more likely to benefit patients with both AR-V7–negative and AR-V7–positive test results in this group (Figure 3C). Flowcharts are provided for recommended use of this test when the risk score is (Figure 4A) or is not (Figure 4B) available.

Figure 3. Androgen Receptor Splice Variant 7 (AR-V7), Therapy, and Overall Survival.

A, Overall survival for low risk only for all 4 treatment-biomarker result groups. B, Overall survival for high risk only for all 4 treatment-biomarker result groups. Six observations (beyond 36 months) are attenuated by the graph axes. C, Forest plot of hazard ratios derived from Cox model. ARSi indicates androgen receptor signaling inhibitors.

Figure 4. Treatment Selection With Androgen Receptor Splice Variant 7 (AR-V7).

A, Recommended decision guide for use of AR-V7 test result with risk score. B, Recommended decision guide for use of AR-V7 test result without risk score. ARSi indicates androgen receptor signaling inhibitors; mCRPC, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; and OS, overall survival.

Discussion

The study results validate the clinical utility of the Epic Sciences nuclear-localized AR-V7 assay to inform the choice between ARS inhibitors or taxanes for patients with mCRPC who are in need of a treatment change in the second-line or greater therapy setting. Validation was established by performing an independent, multicenter, cross-sectional retrospective-prospective study evaluating an analytically valid assay, in which the treatment decisions were made without knowledge of and independent of AR-V7 status, the processing laboratory was blinded to patient outcomes, and the samples were analyzed using appropriate statistics with predefined clinical end points.

Patients who tested negative for AR-V7 had better OS with ARS inhibitors than with taxanes, whereas patients who tested positive for AR-V7 had a demonstrated survival advantage when treated with taxanes. This effect was most prominent for patients classified as high risk, using conventional prognostic factors for the mCRPC population. The validation and demonstration of the clinical utility of nuclear-localized AR-V7 status in CTCs followed the path for biomarker development by completing all steps in the analytic validation of the assay to show that it was fit for the purpose of rigorous clinical validation in which the assay result was studied to determine OS.

Emerging preclinical and clinical data in mCRPC suggest that AR-V7 is only one mechanism of resistance to ARS inhibition that might exist between patients or within an individual patient.9,26,27,28 Other mechanisms include mutations in the receptor, AR gene rearrangements, and alterations to AR-related genes, proteins, and enzymes that stimulate AR signaling.26,27,29 Nuclear-localized AR-V7 expression in CTCs is most often observed in only a subset of CTCs within a patient sample,22 which does not preclude the likelihood that multiple diverse mechanisms may be present and concurrently contributing to the resistant state. This finding is consistent with a recent report that examined CTC phenotypic heterogeneity indices in the same second-line or greater treatment decision context and found that higher CTC heterogeneity was also associated with superior outcomes with taxanes vs ARS inhibitors.28 Evidence of subclonal CTC genomics of AR-dependent and AR-independent signaling drivers co-occurring within the same patient sample were also observed in that study, further supporting the concept that multiple mechanisms of resistance co-occur. More important, additional biomarkers to further stratify differential survival of patients with mCRPC by therapy are needed and should follow a similar stepwise validation process as the nuclear-localized AR-V7 assay. Further validation is ongoing.

Clinically, initiation of a second ARS inhibitor after progression on a previous ARS inhibitor has shown a shorter duration of PSA responses than with the first-line therapy, with most patients failing to demonstrate a decrease in PSA level.2,3 More recently, there have been cautionary studies against reliance on nonvalidated surrogate outcome measures in lieu of OS.30 In the context of decisions about second-line or greater mCRPC therapy, and despite the lack of decreases in PSA level with ARS inhibition, many patients do have durable stable disease. Given these objective data, the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 3 has implemented the use of “no longer clinically benefiting” as a metric to determine the continued overall benefit of a therapy despite the lack of a PSA response as traditionally defined or in the setting of a slow increase in PSA level after an initial decrease.23 More important, for this AR-V7 analysis, the use of OS as the end point is critical in understanding the ability of the biomarker to guide treatment selection for this context of use, given the reduced power of PSA to guide treatment selection in later lines of disease. Perhaps not surprisingly, ARS inhibition was associated with superior OS compared with taxanes for patients with AR-V7–negative disease.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that patients were not prospectively randomized to treatment based on the biomarker results, addressed in part through the use of risk scores in the analysis to mitigate confounding between treatment and underlying patient risk for which latent, unknown imbalances might not be captured by the included features.

Conclusions

In the context of second-line or greater mCRPC clinical decisions in which an ARS inhibitor is being considered, the use of the Epic Sciences nuclear-localized AR-V7 test has demonstrated clinical utility as an assay with OS as an end point. The test should be considered for patients for whom increased OS is an objective. For patients with many comorbidities or who refuse a chemotherapeutic option, the AR-V7 test can still aid in patient management by identifying ARS inhibition–resistant disease for the purpose of directing patients to clinical trials or palliative care.

eFigure. Risk Score Generation

References

- 1.Gillessen S, Attard G, Beer TM, et al. Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer: the report of the Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference APCCC 2017. Eur Urol. 2018;73(2):178-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schrader AJ, Boegemann M, Ohlmann CH, et al. Enzalutamide in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients progressing after docetaxel and abiraterone. Eur Urol. 2014;65(1):30-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rathkopf DE, Antonarakis ES, Shore ND, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of apalutamide (ARN-509) in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with and without prior abiraterone acetate and prednisone. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(14):3544-3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Bono JS, Chowdhury S, Feyerabend S, et al. Antitumour activity and safety of enzalutamide in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer previously treated with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone for ≥24 weeks in Europe [published online August 22, 2017]. Eur Urol. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggarwal RR, Feng FY, Small EJ. Emerging categories of disease in advanced prostate cancer and their therapeutic implications. Oncology (Williston Park). 2017;31(6):467-474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh WK, Miao R, Vekeman F, et al. Real-world characteristics and outcomes of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer receiving chemotherapy versus androgen receptor-targeted therapy after failure of first-line androgen receptor-targeted therapy in the community setting [published online June 19, 2017]. Clin Genitourin Cancer. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henzler C, Li Y, Yang R, et al. Truncation and constitutive activation of the androgen receptor by diverse genomic rearrangements in prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conteduca V, Wetterskog D, Sharabiani MTA, et al. ; PREMIERE Collaborators; Spanish Oncology Genitourinary Group . Androgen receptor gene status in plasma DNA associates with worse outcome on enzalutamide or abiraterone for castration-resistant prostate cancer: a multi-institution correlative biomarker study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(7):1508-1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161(5):1215-1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathkopf DE, Smith MR, Ryan CJ, et al. Androgen receptor mutations in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with apalutamide. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(9):2264-2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Chan SC, Brand LJ, Hwang TH, Silverstein KA, Dehm SM. Androgen receptor splice variants mediate enzalutamide resistance in castration-resistant prostate cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2013;73(2):483-489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qu Y, Dai B, Ye D, et al. Constitutively active AR-V7 plays an essential role in the development and progression of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:7654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Wang H, et al. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):1028-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Luber B, et al. Clinical significance of androgen receptor splice variant-7 mRNA detection in circulating tumor cells of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with first- and second-line abiraterone and enzalutamide. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(19):2149-2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Luber B, et al. Androgen receptor splice variant 7 and efficacy of taxane chemotherapy in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(5):582-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernemann C, Schnoeller TJ, Luedeke M, et al. Expression of AR-V7 in circulating tumour cells does not preclude response to next generation androgen deprivation therapy in patients with castration resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;71(1):1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onstenk W, Sieuwerts AM, Kraan J, et al. Efficacy of cabazitaxel in castration-resistant prostate cancer is independent of the presence of AR-V7 in circulating tumor cells. Eur Urol. 2015;68(6):939-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antonarakis ES, Scher HI. Do patients with AR-V7-positive prostate cancer benefit from novel hormonal therapies? it all depends on definitions. Eur Urol. 2017;71(1):4-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parkinson DR, McCormack RT, Keating SM, et al. Evidence of clinical utility: an unmet need in molecular diagnostics for patients with cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(6):1428-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Punnoose EA, Ferraldeschi R, Szafer-Glusman E, et al. PTEN loss in circulating tumour cells correlates with PTEN loss in fresh tumour tissue from castration-resistant prostate cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2015;113(8):1225-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDaniel AS, Ferraldeschi R, Krupa R, et al. Phenotypic diversity of circulating tumour cells in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2017;120(5B):E30-E44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scher HI, Lu D, Schreiber NA, et al. Association of AR-V7 on circulating tumor cells as a treatment-specific biomarker with outcomes and survival in castration-resistant prostate cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(11):1441-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scher HI, Morris MJ, Stadler WM, et al. ; Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 3 . Trial design and objectives for castration-resistant prostate cancer: updated recommendations from the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 3. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(12):1402-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boffa DJ, Graf RP, Salazar MC, et al. Cellular expression of PD-L1 in the peripheral blood of lung cancer patients is associated with worse survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(7):1139-1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scher HI, Graf RP, Schreiber NA, et al. Nuclear-specific AR-V7 protein localization is necessary to guide treatment selection in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;71(6):874-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A, Coleman I, Morrissey C, et al. Substantial interindividual and limited intraindividual genomic diversity among tumors from men with metastatic prostate cancer. Nat Med. 2016;22(4):369-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gundem G, Van Loo P, Kremeyer B, et al. ; ICGC Prostate Group . The evolutionary history of lethal metastatic prostate cancer. Nature. 2015;520(7547):353-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scher HI, Graf RP, Schreiber NA, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity of circulating tumor cells informs clinical decisions between AR signaling inhibitors and taxanes in metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77(20):5687-5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wyatt AW, Azad AA, Volik SV, et al. Genomic alterations in cell-free DNA and enzalutamide resistance in castration-resistant prostate cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(12):1598-1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prasad V, Kim C, Burotto M, Vandross A. The strength of association between surrogate end points and survival in oncology: a systematic review of trial-level meta-analyses. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1389-1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Risk Score Generation