Abstract

Cancer (the focus of this inquiry) is the leading cause of death among American Indian and Alaska Native women. The purpose of this study was to identify American Indian women cancer survivors’ needs and preferences related to community supports for their cancer experience. This qualitative study examined female American Indian cancer survivors’ needs and preferences about community support. The sample included 43 American Indian women cancer survivors (the types of cancer survivors included cervical cancer: n = 14; breast cancer: n = 14; and colon and other types: n = 15) residing in the Northern Plains region, in the state of South Dakota. Data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis and were collected between June of 2014 and February of 2015. When asked about their needs and preferences, 82% of participants (n = 35) of female American Indian cancer survivors reported at least one of the following most commonly reported themes: cancer support groups (n = 31, 72%), infrastructure for community support (n = 17, 40%), and cancer education (n = 11, 26%). In addition to the aforementioned themes, 33% of participants (n = 14) indicated the need for an improved healthcare system, with 11% (n = 5) of participants expressly desiring the integration of spirituality and holistic healing options. The majority of American Indian women cancer survivor participants of this study identified a need for more community-based support systems and infrastructures to aid with the cancer survivor experience. Results warrant a community approach to raise awareness, education, and support for American Indian cancer survivors.

Keywords: Cancer, American Indians or Native Americans, Women, Community support, Historical trauma and historical oppression

Background

American Indian and Alaska Natives tend to experience alarming health disparities as compared with the general US population. For example, American Indian and Alaska Native women experience cancer, the leading cause of death for such women, at 1.6 times the rate of their white counterparts [1]. Cancer rates and related factors vary by gender, indicating a need to examine American Indian women cancer survivors separately. For example, lung cancer continues to increase for American Indian and Alaska Native women, despite it decreasing for their male counterparts [2]. Although breast cancer death rates are lower for American Indian and Alaska Native women than whites, this varies by age group and region. Moreover, American Indian and Alaska Native women have not experienced the decline in breast cancer death rates that whites have [3]. For both kidney and colorectal cancers, incidence rates were higher for American Indian and Alaska Natives [4], and women in particular experience higher incidence and death rates than both American Indian and Alaska Native males and white women [4]. Given that the Treaty Agreements between the USA and the 567 federal sovereign tribes include a trust responsibility to provide for the health and wellbeing of American Indian and Alaska Natives [1, 5, 6], disparities indicate a failure to uphold this responsibility. Research suggests that American Indian women often rely on support from their communities to deal with a variety of health problems, including in the case of cancer [7].

A considerable body of evidence indicates that support from a cancer survivor’s community is important for patients’ emotional and social well-being and improved short- and long-term recovery, making the exploration of how community programs can be supported warranted [8]. However, research indicates that fewer American Indian individuals receive concordant cancer treatment compared to White patients, highlighting the need for American Indian-specific programs for cancer treatment [9]. Barriers to receiving treatment include a lack of community-driven and culturally congruent care options [10], the need to include their families in care, and options for traditional medicine to be incorporated into their care [10]. Female American Indian cancer survivors’ may also desire community support because it is better suited to addressing some of the social and psychological effects of cancer, in addition to facilitating positive-relationships with the healthcare system [8, 11, 12].

American Indian cancer survivors living in rural areas are more likely to experience infrastructure barriers to accessing cancer screening, treatment, and follow-up care. In addition to providing social and emotional supports, communities may also be uniquely positioned to conduct cancer education and screening programs, especially for survivors in more geographically isolated areas [7, 13, 14]. Community-based programs for cancer survivors are broad, spanning across social and psychological support programs, community education, cancer screening programs, treatment adherence programs, and home health care and patient navigator programs [14, 15]. The need and importance of community-driven programs for American Indian cancer survivors are great because of the long history of inadequate health and social programs, which have often served to exacerbate existing health disparities [10]. Because of the long history of oppression experienced by American Indians, some patients may have ambivalent feelings about participating in programs from those outside the community [10] making community-driven programs especially relevant and needed.

American Indian women are disproportionately burdened by cancer inequalities. However, relatively little research investigates the cancer support needs expressed by female American Indian cancer survivors. Although evidence indicates that community support is associated with positive coping for American Indians with cancer, few studies explicitly focus on community support among American Indian women with cancer [16]. Given that cancer rates and treatment outcomes vary by gender, geographic region, and age, it is important to explore the specific experiences of women living in particular tribes and geographic areas since ethnic identity and culture may also play an important role in impacting the community support experiences of female American Indian cancer survivors. The purpose of this study was to identify American Indian women cancer survivors’ needs and preferences related to community supports for their cancer experience. This study illuminates the qualitative perspectives of female American Indian cancer survivors’ needs and preferences and can inform strategies to reduce the disproportionate burden of cancer inequality experienced by this group.

Methods

Research Design

This study examined female American Indian cancer survivors’ needs and preferences for community support. A community-based participatory research (CBPR) methodology was utilized throughout this study. A community advisory board (CAB) made up of American Indian health care professionals and leaders who work in two American Indian communities, informed the development of the project, its implementation, and interpretation of the study findings. The CAB were responsible for (1) identifying culturally relevant research needs and interests; (2) guiding recruitment of participants and dissemination of results; and (3) enhancing community engagement and community support for research. We used a Qualitative Descriptive study methodology, which is a straight-forward qualitative methodology commonly used to find pragmatic solutions to persistent social problems (e.g., American Indian disparities in cancer care) [17], to examine American Indian women cancer survivors’ perceptions as they are related to needed programs and services. The broad research question was “What are the needs and preferences of American Indian women cancer survivors?” The distinction of the Qualitative Description methodology is that it is not aligned with any one theoretical framework, so it may be used to answer straight forward research questions related to health. It is flexible, in that hues, tones, and influences from relevant theoretical frameworks can be integrated. Qualitative description prioritizes the voices of participants themselves, in contrast to the abstract interpretations of researchers, making it especially appropriate and relevant for working with vulnerable populations to understand cultural nuances [17]. Since highly interpretive researcher analysis is not characteristic of this method, staying close to the data and honoring the explanations of participants is considered an optimum methodology that results in culturally relevant knowledge with applicability to real-world settings, in this case, “what programs do American Indian women cancer survivors need” [17].

Setting and Sample

The study was conducted at the following community-based hospitals: (a) the Avera Medical Group Gynecologic Oncology (Sioux Falls, SD) and (b) the John T. Vucurevich Cancer Care Institute, Rapid City Regional Hospital (Rapid City, SD). These hospitals were selected because they are the primary medical institutions serving American Indian women in the Northern Plains region, in the eastern and western parts of South Dakota, because interviewers needed to be familiar with the culture, lifestyle, resilience, and resistance to historical oppression of cancer survivors. The selection criteria for interviewers were (1) cultural awareness and knowledge of diversity issues and (2) work and interview experience with Indigenous populations. Interviewers received intensive training to mitigate bias in interviewing by the lead author and the CAB and standardized probes and interview guidelines.

Eligibility criteria for participation included the following: (a) the participant having a history of any cancer type within the previous 10 years; (b) completing cancer treatment without signs or symptoms of recurrence at the time of interview; (c) the participant being 18 years or older; (d) the participant residing in South Dakota; and (e) the participant identifying as an American Indian female. Participant recruitment involved three steps: First, a list of cancer survivors was created through the two partner hospitals, and two hospital staff mailed a flyer to cancer patients from this list. A total of 100 flyers were sent to American Indian women cancer survivors. Second, building on the CAB’s community networks, we advertised the research with flyers, newspapers, and public radio announcements, along with word-of-mouth advertising at community agencies and/or churches. Interested persons contacted the lead researcher of this study. Third, individuals who were on the list of cancer survivors or who responded to the advertisement were contacted by interviewers for an initial screening. Forty-six women responded. Three potential participants who had more than 10 years of cancer history were excluded, resulting in the final sample of 43 women. After determining eligibility, an interview was scheduled at the interviewee’s preferred location (i.e., participants’ personal residence, a private room at the hospital, a private conference room at a community church, or the lead author’s office) between June 2014 and February 2015. Prior to the interview, we fully explained the purpose of our study, eligibility criteria, risks/benefits, confidentiality, and provided contact information for the research team. Participants were also informed that their participation would be entirely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time should they become uncomfortable with the study. All participants provided written, signed informed consent. The interview duration was approximately 30 min to 2 h in length, and interviews were audio-recorded. Participants were paid $50 cash for their participation, and an additional gift card was offered to cover travel and participation expenses as needed.

The sample included 43 American Indian women cancer survivors (n = 14 breast cancer, n = 14 cervical cancer, and n = 15 colon and other types of cancer). To assess the different needs and desires of women cancer survivors across different forms of cancer, we were inclusive of cancer types. To determine who was best able to answer our research questions (i.e., American Indian women cancer survivors), and at what point the data reached saturation (i.e., when no new meaningful information/redundancy is gained), we used purposeful sampling. Almost all (97.7%) of participants achieved a high school degree/GED. Participant ages ranged were 32 to 77, (M = 56.33 years, SD = 12.07). Almost half of the sample (49%) reported a monthly household income of less than $1499. Almost one third (32.5%) of participants characterized their health in the poor/fair categories, whereas 67.5% of participants reported their health as being in the good/excellent category. Participants had experienced a variety of types of cancer including the following: cervical (n = 14, 32.6%); breast (n = 14, 32.6%); colon (n = 5, 11.6%); non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (n = 2, 4.7%); lung (n = 2, 4.7%); among others (n = 6, 13.9%). The majority of participants (n = 39, 90.7%) reported having a specific religious affiliation, and 93% of participants reported having medical insurance. The mean length of time for the cancer experienced was 2.42 years (SD = 2.19).

Data Collection

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to data collection from the following institutions: (a) University of South Dakota, (b) Avera McKennan Hospital, (c) Rapid City Regional Health, and (d) Sanford Research Center.

Survey and Interview Tools

The researchers and CAB developed a semi-structured interview guide covering research topics related to women cancer survivors with a focus on the aforementioned community needs identified by the CAB. The CAB edited the guide, ensuring the readability and that the wording was culturally appropriate for American Indian women cancer survivors. Interview guide questions included the following: (a) “Do you have support systems outside of your family? What types of support have you received from them?” (b) “Do you feel supported by the American Indian community? What type of support did they provide?” and (c) “In your opinion as an American Indian woman, what would make life better among American Indian cancer survivors?”

Milne and Oberele’s (2005) strategies for rigor specific to Qualitative Descriptive studies were followed in this study [18], ensuring (a) authenticity to the purpose of the research; (b) credibility or trustworthiness of results; and (c) criticality or intentional decision-making processes. We incorporated these strategies through using a semi-structured and flexible interview guide (facilitating participants ability to speak freely), making sure participants’ voices were heard by probing for clarity throughout the interview, conducting member checks to ensure accurate understanding of participants’ perceptions, and using inductive analysis, so that coding emerged from the data through conventional content analysis. Authenticity was also promoted by examining potential bias and engaging in peer review across co-authors, both of which helped ensure study integrity [18].

Data Analysis

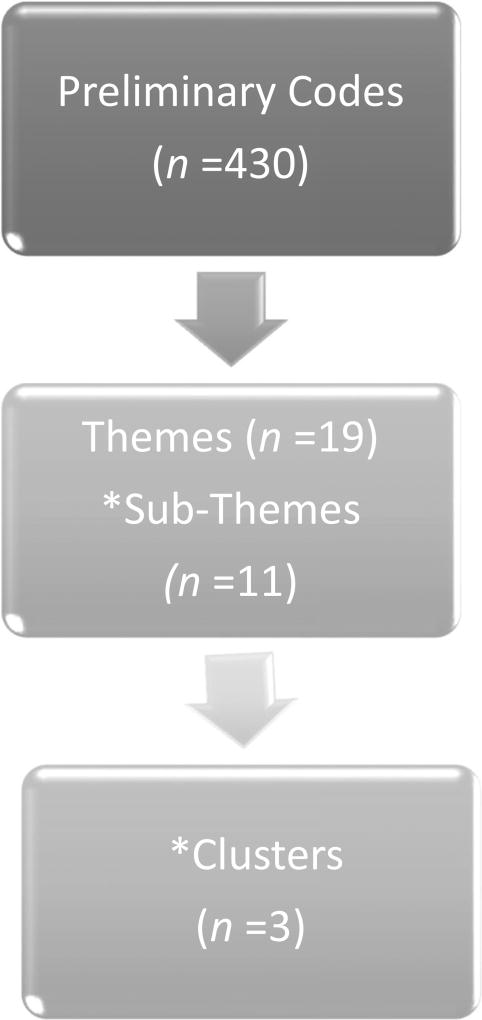

In line with the recommendations for Qualitative Descriptive studies [17–19], data analysis followed the qualitative content analysis, which allowed for inductive themes to be drawn from the raw data [18]. Data analysis followed the following stages (See Fig. 1): (a) listening to the audio recordings and reading the interview transcripts multiple times for immersion in the data, fostering a holistic understanding of data; (b) coding each line of data specifically, adding annotations to communicate key concepts; (c) identifying 430 meaning units (i.e., preliminary codes), which were then sorted into 19 larger themes with subthemes under each (the subthemes related to this article totaled 11); (d) co-authors validate themes and subthemes, indicating no significant differences in themes were identified by cancer type; (e) emergent themes were used to organize codes into three meaningful clusters, or overarching themes, which were defined; and (f) themes with respective quotes were provided to all participants who could be reached for member checking (ensuring data and interpretations were accurate); authors reached out to all participants to engage in member checks up to three times. More than half (n = 23, 53.5%) engaged in the process, though close to half (n = 21, 46.5%) had disconnected phones, and were therefore unreachable. When given the opportunity, participants indicated no changes/amendments to data, themes, or interpretations.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of themes and sub-themes throughout data analysis.

*Sub-themes and clusters are denoted for this article only. Due to space limitations and the scope of this inquiry, overreaching themes could not all be included in this article.'

Results

When asked about their needs and preferences, most study participants reported at least one of the following most commonly reported themes: cancer support groups (n = 31, 72%), infrastructure for community support (n = 17, 40%), and cancer education (n = 11, 26%). Although not the focus of these qualitative results, it is noteworthy that of the 33% of participants who (n = 14) indicated that there was a need for an improved healthcare system, whereas 11% of these participants (n = 5) wanted this health system to include an integration with spiritual and holistic healing options. This information is provided to add contextual information for the reader, but is beyond the scope of this inquiry, which focuses on community supports, rather than the formal health care system. The focus now turns to describing the aforementioned themes.

Cancer Support Groups

Support groups were the most frequently (n = 31) recommended form of support identified by participants and participants reported that these groups assisted participants in counteracting stigma, fostering social connection, and assisting with navigating the complex terrain of cancer survival. As a participant recommended, “Support groups, I think that would be good.” A participant also recommended more support groups and culturally relevant educational materials:

More support groups. Um, there isn’t really even anything online. When I looked up American Indian support groups or Native American education on cancer, there wasn’t anything. And what little there was just an insult to your intelligence. You know, “see Spot run” kind of thing. … I think that’s the big thing, support groups, [and] education.

Many participants indicated that the stigma surrounding sickness and cancer could isolate the cancer survivors who were most in need of connection. One participant went on to recommend more support groups, cancer awareness, and educational programs to counteract the stigma related to cancer:

I think if we had like cancer support groups for women, or if we had someone that they could talk to, like maybe a hotline or something that they could call and just talk to someone; because when I was diagnosed with breast cancer, and I started talking to people—I mean I had friends who had breast cancer—and I never knew I had a friend who was 15 who had breast cancer when she was 14, and she didn’t tell anybody because she didn’t want anybody to feel sorry for her. And for me … I didn’t want people to pity me or feel sorry for me. …I think for people to treat breast cancer patients as, you know, not look at them, like ignore them, or be afraid to talk to them, because I feel like a lot of people have really backed off from me and stopped being my friends because I have breast cancer.

This participant thought that support groups would increase awareness and demystify cancer, and foster communication and support for cancer survivors. Yet, another participant went on to say “I think support groups are good if a person really goes to them. I think they can benefit from them, especially the Native people because, I don’t know how to say this, we’re kind of withdrawn into ourselves.” Similar to the last participant, this survivor indicated that the support from other cancer survivors reduced the fear and stigma that may serve as a disincentive to communicate about cancer.

Participants also indicated that much guidance and understanding is needed to navigate through the many changes related to physical health, emotional wellbeing, and identity that cancer can be a catalyst for. Many participants indicated the need for support from fellow cancer survivors—which they reported could come from women in support groups—and that this support could help women with cancer understand the changes they were experiencing and how to cope. Still, a participant emphasized:

“I think they [survivors] need to share. I think they need to talk about their experiences. We shouldn’t have to reinvent the wheel and think of everything ourselves. We should be learning from the people that came before us.” A participant explained:

There should be maybe a group of people or someone there who is able to help you, because…when I went to do the mammogram and then when I found out I had a lump, and…then I didn’t have anywhere else to go…I didn’t know where to go from there.

This participant indicated that the need for pragmatic knowledge about how to handle symptoms of cancer was great, and guidance could be highly beneficial. One participant recalled how the physical changes caused by cancer treatment affected her identity as a woman and how she received support in understanding how to cope with these changes, both pragmatically and emotionally. She described one such support group,

They [support group members] go over like, how to wear the wigs, they-they set you up with that. They show you how to wear makeup, they give you a nice whole big goody bag of, full of makeup and umm because as a woman… your appearance is a lot. And I noticed myself all the sudden feeling, I have no more eyelashes, I have no more eyebrows. And the support system we went to, the one in the evening, they gave you all that. They showed you [how to] apply all of this makeup, where… maybe I would’ve known but the thing is-is they supported you, your insecurities in your looks…You know, and they encouraged you that it’s ok to feel that way. So that was one of the support groups that as a woman, I really enjoyed. That was a really scary part in a woman’s life, is being bald… All the sudden I didn’t have any hair to fix.

As indicated by these participants, support groups enabled participants to cope with their changing identity as a woman. Finally, a participant thought it was important to “Have support groups so they can tell their story, how things are happening with them, and what stage of cancer they’re in, you know, those kinds of things help if they come out and talk about it.”

Infrastructure for Community Support

Many participants (n = 17) expressed the need for infrastructures in the community(s) to facilitate building community support. One participant had the idea:

What I was thinking. If there was like a building or something there. Like, someone in the community, like we could go sit there and like, have something for us to do, like … like those puzzles or like a little community thing. We could just get together and just visit or build puzzles, or like a little sewing, being inside here…and you know, different little things.

The need for infrastructures for community support that were inclusive of families was emphasized by several participants. A participant suggested:

I think one thing would be a physical location…and not to set yourself so apart that cancer is the only thing that defines you, but have a place where you can go … a place where they can meet people in common…Maybe we have some rooms, some side rooms where families could come there and meet each other’s families, because it’s not just the patient, the whole family has cancer. … Really you all go through it together.

A participant emphasized the need for “Their families [to] become more aware of it too, and it’s not something that you can share with your family.”

Community Education

Education for community members and women with cancer was an expressed need by many (n = 11). A participant indicated “I think if we had more breast cancer awareness and more education, and maybe just someone to talk to for the women.” Another participant thought there needed to be “Support. … Educate each other. Um, uh, I would say just talking to each other about it. And then educating the public.” Likewise, a participant stated:

I think probably just knowing more about it. Like even now I don't really know that much.…I was so worried that I just kind of blocked it out. I did a lot of reading and I tried to educate myself … So maybe it's just more education.

Another participant thought:

If people would go into the schools and talk to the young girls about it too, I mean for me breast cancer isn’t a respecter of persons, and when kids are in school and they understand it more, because with my 15-year-old son he started acting out and getting in trouble because he was angry with me because I had breast cancer. But I think that if the kids in school knew about breast cancer and survival rate, the kids wouldn’t feel so bad about it.

Part of that community education could include honoring survivors, as a participant stated:

They have several members … they do dinners and honorings [sic] for people, and just last week there was a pow wow over there someplace and here they had a big honoring for these four women cancer survivors; so these women went there and I guess during this past year or two they had various types of cancer but they survived. And they gave them a whole bunch of gifts and a star quilt and all kinds of stuff and took them out to the pow wow center and honored them.

Discussion

When the female American Indian cancer survivors in this study were asked about their needs and preferences for community support, participants identified the need for cancer support groups, infrastructure for community support, and cancer education in detail. In recommending support groups, participants emphasized the benefit of learning from fellow cancer survivors. Many study participants thought that American Indian women tend to experience stigma surrounding cancer, which impairs their ability to reach out and find support for their cancer experience. Some participants reported being treated differently as a result of having cancer and emphasized the need for community education and awareness to counteract the misunderstanding and stigma that may surround cancer. Women also experienced complex and rapidly shifting physical, emotional, and identity changes around their cancer experiences, and the support of other cancer survivors was integral for them to successfully navigate these changes. Whether it be understanding how to deal with hair loss due to treatment and the concomitant emotional and identity changes this physical change may cause or knowing how to navigate the healthcare system, support for these life events was desired by participants. Community infrastructure and having places to meet for cancer support groups and other recreational events were expressed needs, with participants recommending community buildings for the facilitation of community support. As participants stated, cancer affects the whole family and cancer support should be inclusive of the families of cancer survivors. Finally, the need for community education was reported by participants, and suggestions to educate youth in schools and honor survivors through American Indian traditions were recommended.

Future Research and Limitations

The findings of this qualitative study are not generalizable beyond their specific context. The focus of this qualitative study was to identify the types of community support and the need for community support female American Indian cancer survivors reported. Though differences across participants with differing types of cancer were not found, future studies should replicate or extend this work with larger samples or quantitative studies. Additionally, the findings of this study are limited to their specific tribal and geographic scope. Given heterogeneity across tribes and between urban and rural areas, differences need to be examined with regard to their specific implications for community support for cancer survivors [5]. Cross-cultural research is needed to further investigate whether the stigma surrounding communicating about cancer varies by ethnic background, tribe, or region.

These results also suggest that the inclusion of the community in cancer education, treatment and screening programs, is a needed area for further research. Because more research is needed, communities may also be instrumental in helping recruit women to participate in clinical trials, an area where American Indian women are often under-represented [20]. Thus, American Indians need to be included in randomized control trials to offer evidence-based and culturally relevant programs. Social media campaign programs may also be an area where future research and program development is needed since there is evidence that more and more cancer survivors and their families are receiving cancer-related information from these sources [21]. This may be especially relevant for individuals in rural areas where access to resources is limited [21]. Because only phone number contact information was collected for participants, the ability to contact participants by other means of follow-up was limited.

Implications for Practice and Conclusion

The majority of American Indian women cancer survivors in this study identified a need for more community-based support systems and infrastructures to aid with the cancer survivor experience. Communities represent a promising resource for conducting and designing culturally relevant programs such as cancer screening and community education programs [13, 22], and facilitating and running support groups [23]. Some culturally relevant programs have been aimed at American Indian cancer survivors. For example, talking circles have been utilized in some programs and have been linked with quicker recovery and improved health outcomes and may be a promising area where community programs could be utilized as a way to support American Indian women with cancer [24].

Additionally, the use of “telehealth” support groups among American Indian and Alaska Native cancer survivors has been explored with promising results [25], suggesting that creative options for linking geographically distant women may be a way to provide some of these programs [25]. Patient navigator programs (which can assist patients with understanding treatment protocols and options, financial and transportation issues and care coordination) are an additional promising area where community programs can be instrumental [14, 15]. Though many American Indians report preferring face-to-face contact for these programs, American Indian individuals are increasingly reporting being open to other types of communication such as e-mail and social media, which may be avenues to bolster social support, which was clearly instrumental for women cancer survivors [14].

The importance of communities running these programs may be especially important for American Indian women due to their history of marginalization and oppression. The unique stressors experienced by American Indian cancer survivors in this study suggest that community programs may play a particularly important role for female cancer survivors and highlight the need for an investigation of how community programs can be utilized. American Indian women may be more likely to participate in screening programs that are run by their tribal community [13, 14]. However, despite this need, there is evidence to suggest that the medical community may not always be supportive or help facilitate community-driven programs [7, 10, 14]. Because of the legacy of historical oppression in American Indian communities, an analysis of the role community programs have in female cancer survivors’ treatment and recovery is especially important. Even after the physical effects of cancer have been resolved, women’s social and psychological health often continues to suffer following cancer and may require additional support from a woman’s community [8].

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (U54MD008164 by Elliott) from the National Institutes of Health to Soonhee Roh, PhD.

Funding This work was supported, in part, by Award K12HD043451 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (Krousel-Wood-PI; Catherine Burnette-Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) Scholar).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Catherine E. Burnette, Email: cburnet3@tulane.edu.

Soonhee Roh, Email: Soonhee.Roh@usd.edu.

Jessica Liddell, Email: jliddell@tulane.edu.

Yeon-Shim Lee, Email: yl375@sfsu.edu.

References

- 1.Espey DK, Jim MA, Cobb N, Bartholomew M, Becker T, Haverkamp D, Plescia M. Leading causes of death and all-cause mortality in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:S303–S311. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plescia M, Henley SJ, Anne P, Michael Underwood J, Rhodes K. Lung cancer deaths among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 1990–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:S388–S395. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White A, Richardson LC, Li C, Ekwueme DU, Kaur JS. Breast cancer mortality among American Indian and Alaska Native women, 1990–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:S432–S438. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perdue David G, Haverkamp Donald, Perkins Carin, Makosky Daley Christine, Provost Ellen. Geographic variation in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality, age of onset, and stage at diagnosis among American Indian and Alaska Native people, 1990–2009. American Journal of Public Health; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bureau of Indian Affairs. What we do. [Accessed 5/12 2017];2017 https://www.bia.gov/index.htm.

- 6.U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Native American health care disparities briefing: executive summary 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guadagnolo BA, Cina K, Helbig P, Molloy K, Reiner M, Cook EF, Petereit DG. Medical mistrust and less satisfaction with health care among Native Americans presenting for cancer treatment. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20:210–226. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sammarco Angela, Konecny Lynda M. Quality of life, social support, and uncertainty among Latina breast cancer survivors. 2008;35 doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.844-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javid Sara H, Varghese Thomas K, Morris Arden M, Porter Michael P, He Hao, Buchwald Dedra, Flum David R. Guideline-concordant cancer care and survival among American Indian/Alaskan Native patients. Cancer. 2014;120:2183–2190. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canales MK, Weiner D, Samos M, Wampler NS, Cunha A, Geer B. Multi-generational perspectives on health, cancer, and biomedicine: Northeastern Native American perspectives shaped by mistrust. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22:894–911. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sapp AL, Trentham-Dietz A, Newcomb PA, Hampton JM, Moinpour CM, Remington PL. Social networks and quality of life among female long-term colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer. 2003;98:1749–1758. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyatt Gwen, Friedman Laurie L. Long-term female cancer survivors: quality of life issues and clinical implications. Cancer Nurs. 1996;19:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199602000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown Sylvia R, Joshweseoma Lori, Saboda Kathylynn, Sanderson Priscilla, Ami Delores, Harris Robin. Cancer screening on the Hopi reservation: a model for success in a Native American community. J Community Health. 2015;40:1165–1172. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0043-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris Raymond, Van Dyke Emily R, Ton Thanh GN, Nass Carrie A, Buchwald Dedra. Assessing needs for cancer education and support in American Indian and Alaska Native communities in the Northwestern United States. Health Promot Pract. 2016;17:891–898. doi: 10.1177/1524839915611869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burhansstipanov L, Dignan M, Jones KL, Krebs LU, Marchionda P, Kaur JS. A comparison of quality of life between Native and non-Native cancer survivors. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27:106–113. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0318-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer JE, Englert JJ, Michalek AM, Canfield P, Mahoney MC. American Indian cancer survivors: exploring social network topology and perceived social supports. J Cancer Educ. 2005;20:23–27. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2001s_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan-Bolyai S, Bova C, Harper D. Developing and refining interventions in persons with health disparities: the use of qualitative description. Nurs Outlook. 2005;53:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milne J, Oberele K. Enhancing rigor in qualitative description: a case study. J Wound Ostomy, Continence Nurs. 2005:413–420. doi: 10.1097/00152192-200511000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, Gary TL, Shari B, Chris Gibbons M, Tilburt J, Baffi C, Tanpitukpongse TP, Wilson RF. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112:228–242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gage-Bouchard Elizabeth A, LaValley Susan, Warunek Molli, Beaupin Lynda Kwon, Mollica Michelle. Is cancer information exchanged on social media scientifically accurate? Journal of Cancer Education. 2017:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s13187-017-1254-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Struthers Roxanne, Eschiti Valerie S. The experience of Indigenous traditional healing and cancer. Integr Cancer Ther. 2004;3:13–23. doi: 10.1177/1534735403261833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelusi Jody, Krebs Linda U. Understanding cancer-understanding the stories of life and living. J Cancer Educ. 2005;20:12–16. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2001s_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker Sara A, Affonso Dyanne D Madonna Blue Horse Beard. Talking circles: Northern Plains tribes American Indian women’s views of cancer as a health issue. Public Health Nursing; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doorenbos AZ, Eaton LH, Haozous E, Towle C, Revels L, Buchwald D. Satisfaction with telehealth for cancer support groups in rural American Indian and Alaska Native communities. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14:765–770. doi: 10.1188/10.CJON.765-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]