Abstract

Latent class analysis (LCA) has proven to be a useful tool for identifying qualitatively different population subgroups who may be at varying levels of risk for negative outcomes. Recent methodological work has improved techniques for linking latent class membership to distal outcomes; however, these techniques do not adjust for potential confounding variables that may provide alternative explanations for observed relations. Inverse propensity score weighting provides a way to account for many confounders simultaneously, thereby strengthening causal inference of the effects of predictors on outcomes. Although propensity score weighting has been adapted to LCA with covariates, there has been limited work adapting it to LCA with distal outcomes. The current study proposes a step-by-step approach for using inverse propensity score weighting together with the “Bolck, Croon, and Hagenaars” approach to LCA with distal outcomes (i.e., the BCH approach), in order to estimate the causal effects of reasons for alcohol use latent class membership during the year after high school (at age 19) on later problem alcohol use (at age 35) with data from the longitudinal sample in the Monitoring the Future study. A supplementary appendix provides evidence for the accuracy of the proposed approach via a small-scale simulation study, as well as sample programming code to conduct the step-by-step approach.

Keywords: latent class analysis, causal inference, propensity scores, alcohol use, motives, reasons for drinking

Latent class analysis (LCA) has proven to be a useful tool in prevention research. It has been used in recent years to identify a wide array of within-individual patterns, such as exposure to risk factors (Lanza & Rhoades, 2013), substance use and other health behaviors (Cardoso, Goldbach, Cervantes, & Swank, 2016; Gilreath, Astor, Estrada, Benbenishty, & Unger, 2014; Héroux et al., 2012), and expectancies, attitudes and norms related to decision-making (Stapleton, Turrisi, Cleveland, Ray, & Lu, 2014). This work has contributed to our understanding of the etiology underlying the development of many negative behavioral and health outcomes targeted by prevention programs, as well as the effects of prevention programs (Jiang et al., 2012; Low, Smolkowski, & Cook, 2016; Spilt, Koot, & van Lier, 2013). As the use of LCA has expanded, increasingly complex research questions have been posed about the roles played by latent class variables in development and prevention. Recently, new methodologies for LCA with distal outcomes (Bakk & Vermunt, 2016; Bray, Lanza, & Tan, 2015; Lanza, Tan, & Bray, 2013; Vermunt, 2010) have made it easier to study the link between latent class membership and an outcome variable. However, these techniques do not explicitly address confounding by variables that may provide alternative explanations for observed relations. That is, although these new developments provide a way to regress an outcome variable on a latent class variable, and in some cases can include control variables (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014), by themselves they do not capitalize on modern approaches to causal inference. This is a critical limitation for prevention research and the identification of causal mechanisms leading to negative outcomes.

There are numerous approaches to causal inference, many of which are based on the propensity score (e.g., matching, subclassification, weighting). For an accessible introduction to propensity scores for causal inference readers are referred to Lanza, Moore, and Butera (2013). In particular, inverse probability weighting based on the propensity score has become popular in prevention research, and has been used to examine causal effects of time-invariant (Coffman, Caldwell, & Smith, 2012; Varvil-Weld, Crowley, Turrisi, Greenberg, & Mallett, 2014) and time-varying (Bray, Almirall, Zimmerman, Lynam, & Murphy, 2006) exposures and mediators (Coffman & Zhong, 2012) and can accommodate other important aspects of developmental models, such as moderators of causal effects (Green & Stuart, 2014). Importantly, the use of inverse propensity score weighting has already been demonstrated with LCA with covariates (Lanza, Coffman, & Xu, 2013; Lanza, Schuler, & Bray, 2016). In these demonstrations, one of the causal effects of interest was the average exposure effect (ATE; i.e., average treatment effect; causal effect of an exposure for the entire population) of a non-randomized, observed, binary exposure on a latent class variable, which (by definition) was unobserved and multinomial. Such an approach is useful for understanding causal antecedents of latent class membership, but not consequences of membership. In the current study, we reverse the direction of the causal effect of interest and focus on the ATE of a non-randomized, latent, multinomial exposure (i.e., a latent class variable) on an observed, binary outcome. That is, we propose an approach for implementing inverse propensity score weighting with the currently recommended analytic approach to LCA with distal outcomes. The use of inverse propensity score weighting with a latent class exposure was considered previously by Schuler (2013), Schuler, Leoutsakos, and Stuart (2014), and Yamaguchi (2015), all of whom compare alternative approaches. Yamaguchi (2015) considers theoretical and technical details in depth.

We demonstrate our proposed approach by examining the link between patterns of reasons for alcohol use during the transition out of high school and later problem alcohol use. Reasons for alcohol use have been associated with alcohol use and problem alcohol use (Patrick, Evans-Polce, Kloska, Maggs, & Lanza, in press; Patrick & Schulenberg, 2011; Patrick, Schulenberg, O’Malley, Johnston, & Bachman, 2011) and represent an important potential target for prevention programs. For example, drinking to cope with negative emotions may be a more important risk factor than drinking socially (e.g., see Merrill, Wardell, & Read, 2014; Patrick et al., 2011). Based on the idea that multiple reasons may co-occur within individuals, previous research has used LCA to identify patterns of reasons for alcohol use (Coffman, Patrick, Palen, Rhoades, & Ventura, 2007; Stapinski et al., 2016), marijuana use (Patrick, Bray, & Berglund, 2016), and e-cigarette use (Evans-Polce, Patrick, & Miech, 2017). These studies used LCA with covariates or LCA with distal outcomes either to predict patterns of reasons from covariates or to predict outcomes from patterns of reasons.

However, established associations have been correlational in nature. For example, Patrick et al. (2016) examined associations between patterns of reasons for marijuana use at ages 19/20 and problem marijuana use at age 35. Although they were able to control for several variables in the outcome analysis (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, parental education), the significant effects of latent class membership on the outcome do not represent ATEs because a rigorous approach to adjusting for confounding was unavailable. Critically, if adolescent patterns of reasons for use are associated with later outcomes, even after using causal inference methods to account for differences across people with different patterns, it provides evidence that patterns of reasons could be used to screen individuals into prevention programs and/or tailor the content of programs. Here, we examine associations between patterns of reasons for alcohol use at age 19 and problem alcohol use at age 35, and we use inverse propensity score weighting as a rigorous approach to adjust for many potential confounders at age 18 and to estimate ATEs. The approach proposed here can be used generally to estimate ATEs of latent class variables on distal outcomes: it accounts for both the latent class measurement model and the propensity for particular exposure group membership (i.e., latent class membership) in order to estimate an unbiased causal effect of latent class membership on a distal outcome.

The Current Study

The purpose of the current study is to provide a step-by-step empirical example of how to apply inverse propensity score weighting with a latent class exposure. This example is conducted with data from the U.S. national Monitoring the Future (MTF) study and estimates the causal effect of reasons for alcohol use at age 19 on later problem alcohol use at age 35.

A Step-By-Step Example

The Causal Question

By estimating a set of ATEs, we are seeking to answer the following specific research question: What differences in problem alcohol use at age 35 would be expected if all individuals in the population had a certain pattern of reasons for alcohol use at age 19, compared to if all individuals in the population had a different pattern of reasons? In particular, we focus on the ATEs for differences in problem use vs. non-problem use or abstinence at age 35 if (a) all individuals in the population had a pattern of reasons for alcohol use at age 19 labeled Enhancement Reasons, compared to if all individuals in the population had a pattern labeled Few Reasons and (b) all individuals had a pattern labeled Coping Reasons, compared to if all individuals had a pattern labeled Enhancement Reasons. Following standard notation (e.g., McCaffrey et al., 2014) for observed exposures, we define the ATE of membership in one particular latent class versus another as follows. Let Yi[t] be the value on the distal outcome Y which would have been observed if individual i had actually belonged to latent class t; this may or may not be the counterfactual for a given i and t, because class membership is unknown. Then, the ATE of membership in class t versus class t′ is defined as the expectation E(Y[t] − Y[t′]) taken over all individuals (i.e., all values of i) in the population.

Participants

The example used longitudinal data from the MTF study. Annually, MTF collects nationally representative data from about 15,000 U.S. high school seniors (i.e., 12th graders; Miech et al., 2017); approximately 2,450 individuals from each cohort are selected for longitudinal follow-up (Schulenberg et al., 2017). The sample included senior year cohorts from 1976 to 1998 who provided data at age 35 from 1993 to 2015; the sample included all individuals who (1) were selected for longitudinal follow-up; (2) reported alcohol use in the past 12 months at age 19; and provided data on (3) reasons for alcohol use at age 19; (4) all confounders at age 18; and (5) alcohol use and alcohol use problems at age 35. Only those individuals who reported using alcohol in the past 12 months were asked about their reasons for use. Note that MTF uses multiple randomly assigned forms to decrease respondent burden; reasons for alcohol use were included on one form (of five from 1976–1988, and of six from 1989–2015). All analyses used attrition weights to adjust for attrition from ages 18 to 35, calculated as the inverse of the estimated probability of participation at age 35, based on several demographic, educational, and substance use variables, as well as the original sampling weight correcting for over-sampling of substance users at age 18. The weighted analytic sample size was 6,572 (52.9% female; 83.1% White, 7.3% Black, 4.8% Hispanic, 4.8% other).

Measures

Potential confounders

The example considered 15 potential confounders at age 18: cohort (1976 to 1998), gender (male vs. female), race (White vs. Black, Hispanic, Other), living in a two-parent family (yes vs. no), parents’ highest level of education (some college or more vs. high school graduate or less), average grades in high school (A to D), college prepatory curriculum in high school (yes vs. no), definitely planned to graduate from a 2-year or 4-year college (yes vs. no), number of days skipped school in the past month (0 to 11+), importance of religion (not important to very important), average number of nights out with friends per week (<1 to 6–7), number of cigarettes smoked in past month (0 to 2+ packs per day), binge drinking (i.e., 5+ drinks in a row) in past two weeks (0 to 10+ times), marijuana use in past 12 months (yes vs. no), and other illegal substance use in past 12 months (yes vs. no). Weighted descriptive statistics for all potential confounders are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Weighted Descriptive Statistics for the Potential Confounders, Latent Class Indicators, and Outcome

| Potential Confounders |

Mean (Std. Dev.) or Frequency |

Range or Valid % |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | 1986.5 (7.4) | 1976–1998 | |

| Gender | Female | 2273 | 52.9 |

| Male | 2027 | 47.1 | |

| Race | White | 3572 | 83.1 |

| Black | 314 | 7.3 | |

| Hispanic | 207 | 4.8 | |

| Other | 206 | 4.8 | |

| Living in two parent family | No | 931 | 21.7 |

| Yes | 3369 | 78.4 | |

| Parents’ highest level of education | High school or less | 1545 | 35.9 |

| Some college or more | 2755 | 64.1 | |

| Average grades in high school | 6.1[B to B+] (2.4) | 1[D]-9[A] | |

| Took college prep curriculum | No | 1762 | 41.0 |

| Yes | 2537 | 59.0 | |

| Definitely plans to graduate college | No | 1846 | 42.9 |

| Yes | 2454 | 57.1 | |

| No. days cut school in past 30 | 1.7[0 to 1 day] (1.5) | 1[0 days]-7[11+ days] | |

| Importance of religion | 2.6[little to pretty imp] (1.2) | 1[not imp]-4[very imp] | |

| Ave no. days per wk going out | 3.5[2 to 3 eves] (1.5) | 1[<1 eves]-6[6–7 eves] | |

| Smoked cig in past 30 days | 1.7[0 to <1 cig/day] (1.5) | 1[0 cigs]-7[2+ pks/day] | |

| Drank 5+ drinks in past 2 wk | 1.7[0 to 1 time] (1.4) | 1[0 times]-6[10+ times] | |

| Used marijuana in past 12 mo | 1.7[0 to 1–2 times] (1.8) | 1[0 occs]-7[40+ occs] | |

| Used other substances in past 12 mo | No | 3293 | 76.6 |

| Yes | 1007 | 23.4 | |

|

| |||

| Latent Class Indicatorsa | |||

|

| |||

| To have a good time with my friends | 3428 | 79.7 | |

| Because it tastes good | 2344 | 54.5 | |

| To relax or relieve tension | 2224 | 51.7 | |

| To feel good or get high | 2180 | 50.7 | |

| Because of boredom, nothing else to do | 901 | 21.0 | |

| To get away from my problems or troubles | 808 | 18.8 | |

| Because of anger or frustration | 651 | 15.1 | |

| To fit in with a group I like | 370 | 8.6 | |

| To get to sleep | 324 | 7.5 | |

| To increase effects of other drug(s) | 175 | 4.1 | |

| To seek deeper insights and understanding | 167 | 3.9 | |

| To get through the day | 45 | 1.0 | |

| To decrease/offset effects of other drug(s) | 29 | 0.7 | |

| I am "hooked"--I feel I have to drink | 25 | 0.6 | |

|

| |||

| Outcome | |||

|

| |||

| Problem Alcohol Use | Abstinent/Non-Problem Use | 2011b | 67.6b |

| Problem Use | 966 | 32.5 | |

Each alcohol use reason was reported as ‘marked’ (i.e., endorsed as a reason for use) or ‘unmarked’ (i.e., not endorsed). Reported frequencies and valid %s are for endorsement.

Non-users accounted for 148 participants (5.0%).

Notes. Valid % refers to the percent of non-missing cases.

Exposure: Latent classes of reasons for alcohol use

At age 19, participants were asked, “On how many occasions (if any) have you used alcohol during the last 12 months?” (1=0 occasions, 2=1–2 occasions, 3=3–5 occasions, 4=6–9 occasions, 5=10–19 occasions, 6=20–39 occasions, 7=40 or more occasions). Non-users were excluded from analyses because they were not asked questions about reasons for use. At age 19, participants who indicated they had used alcohol at least once in the past 12 months were asked, “What have been the most important reasons for your using alcohol? (Mark all that apply.)” Responses to the 14 reasons were dichotomous (marked vs. unmarked). Reasons could be broadly categorized as social and recreational, coping with negative mood and experiences, utility and pleasure of effects, and compulsive use (see Patrick et al., 2011). These 14 binary variables represent the latent class indicators. Weighted descriptive statistics for all latent class indicators are shown in Table 1.

Outcome: Problem alcohol use at age 35

At age 35, participants who indicated they had used alcohol in the past 5 years were asked, “Think back over the last five years. Did your use of alcohol cause you any of the following problems?” (0=no, 1=a little, 2=some, 3=a lot; coded as none vs. any). The 16 problems included, for example, “Caused you to behave in ways that you later regretted” and “Hurt your relationship with your spouse/partner or girlfriend/boyfriend.” This measure does not provide a clinical diagnosis of alcohol use disorder, but items cover 8 of the 11 DSM-5 criteria for alcohol use disorder (Patrick et al., 2011; Schulenberg et al., 2015). For the outcome analysis, participants were categorized as problem users (i.e., had affirmative responses to two or more criteria; see Schulenberg et al., 2015) or abstinent/non-problem users (i.e., had not used alcohol in the past 5 years or had used alcohol in the past 5 years but did not meet criteria for disorder).1 Weighted descriptive statistics for the outcome are shown in Table 1.

Step-by-Step Analytic Strategy

Step 1: Conduct latent class model identification and selection

LCA was used to identify unique patterns of reasons to use alcohol. LCA is a type of finite mixture model that uses manifest items with categorical responses to divide a population into a set of mutually exclusive and exhaustive latent classes (Collins & Lanza, 2010). In a standard LCA, two sets of parameters are of most interest. Latent class membership probabilities describe the distribution of the classes in the population. Item-response probabilities describe class-specific probabilities of providing particular responses to the latent class indicators. Classes are interpreted and named based on the patterns of item-response probabilities.

Models with 1–6 classes were compared using penalized fit criteria (e.g., AIC, BIC), solution stability, and theoretical interpretability; multiple sets of random starting values were used to assess model identification. Model fit and selection information are shown in Table 2; we selected the 4-class model for interpretation and further analysis, and posterior probabilities from this model were retained for use in Step 2. For information about recommended approaches to LCA model identification and selection, interested readers are referred to Collins and Lanza (2010) and Lanza, Bray, and Collins (2016).

Table 2.

Model Fit and Selection Criteria for Reasons for Alcohol Use Latent Class Analyses

| No. of Classes |

LL | p | AIC | BIC | aBIC | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −14969.80 | 14 | 29967.60 | 30051.58 | 30007.09 | 1.00 |

| 2 | −14281.93 | 29 | 28621.86 | 28795.82 | 28703.68 | 0.74 |

| 3 | −14131.44 | 44 | 28350.88 | 28614.82 | 28475.02 | 0.70 |

| 4 | −14045.55 | 59 | 28209.11 | 28563.03 | 28375.56 | 0.72 |

| 5 | −13993.39 | 74 | 28134.78 | 28578.68 | 28343.55 | 0.66 |

| 6 | −13938.12 | 89 | 28054.237 | 28588.12 | 28305.33 | 0.61 |

Notes. Models with more than 6 classes were not considered due to difficulty replicating the loglikelihood with multiple sets of random starting values. Bold font indicates the selected model.

LL = loglikelihood; p = number of free parameters; AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; aBIC = sample size adjusted BIC.

Parameter estimates for the 4-class model are shown in Table 3. Class 1 (.53 prevalence) was characterized by comparatively low probabilities of all of the reasons for alcohol use and was labeled Few Reasons. Class 2 (.27) was characterized by comparatively high probabilities of ‘to have a good time with my friends’ and ‘to feel good or get high’ and comparatively low probabilities of the other reasons and was labeled Enhancement Reasons. Similarly, Class 3 (.17) was characterized by comparatively high probabilities of ‘to relax or relieve tension,’ ‘to get away from my problems or troubles,’ and ‘because of anger or frustration’ and was labeled Coping Reasons. Class 4 (.04) was labeled Diverse Reasons because it was characterized by comparatively high probabilities of all of the reasons for alcohol use.

Table 3.

Parameter Estimates for the 4-Class Model of Reasons for Alcohol Use

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Few Reasons |

Enhancement Reasons |

Coping Reasons |

Diverse Reasons |

||

|

| |||||

| Latent Class Membership Probabilities | 0.53 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.04 | |

|

| |||||

| Overall | Item-Response Probabilities | ||||

| To have a good time with my friends | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.97 | 0.86 | 0.98 |

| Because it tastes good | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0.73 |

| To relax or relieve tension | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.51 | 0.87 | 0.91 |

| To feel good or get high | 0.51 | 0.19 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 0.96 |

| Because of boredom, nothing else to do | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.87 |

| To get away from my problems or troubles | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.76 | 0.74 |

| Because of anger or frustration | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.57 | 0.70 |

| To fit in with a group I like | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.31 |

| To get to sleep | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.36 |

| To increase effects of other drug(s) | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.39 |

| To seek deeper insights and understanding | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.25 |

| To get through the day | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.18 |

| To decrease/offset effects of other drug(s) | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| I am "hooked"--I feel I have to drink | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 |

Notes. Bold font indicates item-response probabilities > 0.50 to facilitate interpretation.

Latent class exposures with more than two classes open the door for numerous causal questions, as is the case with observed multinomial exposures (Imbens, 1999). A researcher may be interested in, for example, estimating the causal effects of (a) membership in one particular latent class versus another particular latent class, (b) membership in one particular latent class versus all other latent classes, or (c) all pairwise comparisons between latent classes. Here, to narrow the scope of the example and focus on the step-by-step approach, we consider the ATEs of membership in the Enhancement Reasons versus Few Reasons and the Coping Reasons versus Enhancement Reasons latent classes. Collectively, these ATEs include approximately 96% of the population and represent comparisons of classes that are expected to be at increasing risk for problem alcohol use based on their configurations of alcohol use reasons.

Step 2. Calculate propensity scores and inverse propensity score weights

The estimated propensity score for individual i, π̂i, is based on a statistical model of selection into an exposure group, here a particular latent class of reasons for alcohol use. Propensity scores can be used to balance exposure groups on many potential confounders of the association between the exposure and outcome simultaneously (Lunceford & Davidian, 2004; Robins, Hérnan, & Brumback, 2000; Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983), here the association between latent class membership of reasons for alcohol use and later problem alcohol use.

When an exposure, T, is observed and binary, propensity score estimates are often obtained using logistic regression: membership in the exposed (T=1) versus not exposed (T=0) group is predicted by the vector of potential confounders, xi. An individual’s propensity score is his/her predicted probability of membership in the group to which he/she belongs, conditional on all potential confounders. Namely, π̂i = P(T = 1|xi) for those in the exposed group and π̂i = P(T = 0|xi) for those in the not exposed group. When the ATE is the estimand of interest, the inverse propensity score weights can be defined as 1/π̂i. The probabilities P(T = 1|xi) are derived from a logistic regression model with all potential confounders (1, …, p) as predictors:

and P(T = 0|xi) = 1 − P(T = 1|xi).

Now suppose that the exposure is multinomial instead of binary (but still observed). If the exposure is multinomial with groups 1, …, nT, estimation of the propensity score needs to be generalized. This can be done by using multinomial logistic regression instead of binary logistic regression. An individual’s estimated propensity score is still his/her probability of membership in the group to which he/she belongs, conditional on all potential confounders:

| (1) |

where I{Ti = t} is defined as 1 if Ti = t and 0 otherwise. Now, however, the probabilities P(T = t|xi) are estimated from a multinomial logistic regression model,

| (2) |

with appropriate identifiability constraints (e.g., the β coefficients for the reference class set to 0 to reflect the constraint that all probabilities must sum to 1). Note that each individual receives only one π̂i because each individual belongs only to one exposure group.

When the exposure is latent, however, each individual’s true exposure group, Ti, is unknown. When Ti is a multinomial latent variable (i.e., latent class variable), a reasonable substitute for the zero-one indicator variable I{Ti = t} is P(Ti = t|xi, ui), the posterior probability of membership in class t given the covariates xi and the latent class indicator variables ui. Thus, we propose a generalized propensity score formula for latent class exposures:

| (3) |

This propensity score accounts for both the effects of the potential confounders and the unknown nature of class membership. Note that each individual still receives only one π̂i, which is a weighted sum: the sum of the probabilies of membership in the exposure groups weighted by the posterior probabilities of membership in the exposure groups. Intuitively, we are broadening the concept of “the group to which he/she belongs” to incorporate imperfectly known group membership. The posterior probabilities P(T = t|xi, ui) for each individual i and class t can be provided by any LCA software package.

When the exposure is latent, the β coefficients in Equation 2 express the associations between covariates (i.e., potential confounders) and latent class membership; several methods exist to estimate these coefficients. Methods proposed to estimate associations between external variables and class membership include, among others, the unadjusted classify-analyze approach (also called a 3-step approach) and an adjusted classify-analyze approach (also called the BCH approach; Bolck, Croon, Hagenaars, 2004; Vermunt, 2010). The unadjusted classify-analyze approach is the traditional approach based on modal assignment where each individual is assigned to the latent class for which he/she has the highest posterior probability. Class membership is then treated as known (e.g., using dummy-coding) in a subsequent analysis model. This approach results in substantially attenuated β coefficients; subsequent approaches have been proposed as alternatives to reduce attenuation. A growing body of literature (e.g., Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014; Bakk & Vermunt, 2016; Bolck, Croon, & Hagenaars, 2004; Dziak, Bray, Zhang, Zhang, & Lanza, 2016) recommends the BCH approach for a wide array of applications. Similar to the unadjusted classify-analyze approach, the BCH approach is based on modal assignment and treatment of class membership as known in a subsequent analysis model. However, this analysis model is weighted to account for uncertainty in the modal assignments. Using the BCH approach prevents external variables from changing the meaning of the latent classes, accounts for uncertainty in modally assigned latent class membership and prevents attenuated β coefficients, and has been shown to perform accurately and robustly in simulations (see Bakk & Vermunt, 2016 and Dziak et al., 2016 for accessible overviews of the BCH approach and comparisons to other approaches). Therefore, we propose the following approach to calculating propensity scores for latent class exposures that makes use of the BCH approach to estimate the β coefficients in Equation 2. A simulation study examining the performance of this proposed approach is available in the online supplementary appendix and at methodology.psu.edu/downloads/appendices/lc-causal-exposures.

First, use the BCH approach to estimate the β coefficients for predicting latent class membership from the potential confounders. Second, substitute these estimated parameters and individuals’ data into Equation 2 and calculate the fitted probabilities for each individual, P(T = t|xi), which are conditional on the potential confounders (i.e., covariates) but not the indicator variables. Third, calculate the estimated propensity score for each individual by combining these fitted probabilities with the posterior probabilities P(T = t|xi, ui) (retained from Step 1 above) using Equation 3. After a propensity score π̂i has been estimated for individual i, the inverse propensity score weight for individual i is calculated as 1/π̂i. Because the MTF study design additionally involves attrition weights (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, Schulenberg, & Miech, 2016), here denoted si, we calculated the final analysis weight for individual i as the product of the attrition weight and inverse propensity score weight, namely si/π̂i. Ridgeway, Kovalchik, Griffin, and Kabeto (2015) recommend the combined use of sampling weights and propensity weights in this way when both are required.

Step 3. Assess overlap and balance

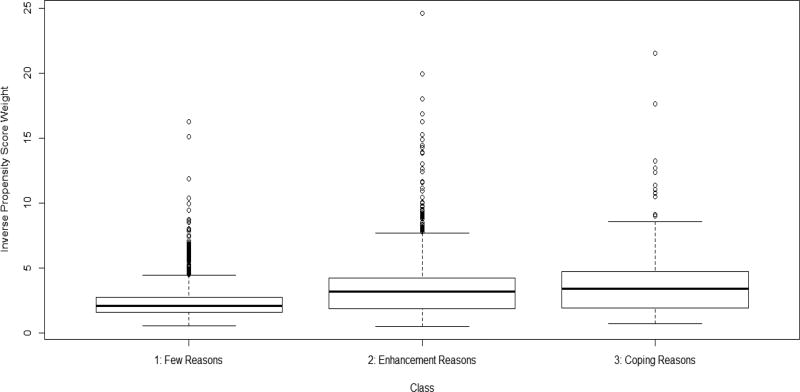

As with any other propensity score-weighted analysis, the quality of the weights needs to be assessed by examining overlap and balance. First, the degree of overlap in the estimated propensity scores between the exposure groups should be assessed. Poor propensity score overlap, where the range of propensity scores for individuals in one exposure group does not correspond to the range of propensity scores for individuals in another group, indicates the groups are too dissimilar to warrant causal inferences. Figure 1 uses boxplots to illustrate the overlap in inverse propensity score weights among the Few Reasons, Enhancement Reasons, and Coping Reasons latent classes that serve as the exposure groups of interest. Although there was not perfect overlap here, it was deemed adequate to warrant causal inferences, particularly for the ATE for Coping Reasons versus Enhancement Reasons.

Figure 1.

Boxplots illustrating the overlap of the inverse propensity score weight distributions for the average exposure effect (ATE) of membership in the Enhancement Reasons versus Few Reasons and Coping Reasons versus Enhancement Reasons latent classes at age 19 on problem alcohol use vs. non-problem use/abstinence at age 35.

Second, the improvement in balance between exposure groups after inverse propensity score weighting should be assessed. The goal of inverse propensity score weighting is to achieve balance; that is, to equate the exposure groups with respect to the distributions of the potential confounders. Balance is desirable because if the distributions of the potential confounders are equal, on average, across exposure groups, the groups may be compared directly. This is similar to balance ideally achieved on potential confounders in a randomized controlled trial. Because these weights can only balance exposure groups with respect to included variables, it is important to include a comprehensive set of potential confounders, and sometimes interactions between them, in the propensity score model. Balance between exposure groups after weighting can be assessed by the standardized mean difference (SMD): the standardized difference in the means or proportions for a given potential confounder between two exposure groups (i.e., latent classes). SMD values close to 0 reflect that means or proportions between the groups are similar on average; SMD values less than 0.20 are typically considered indicative of good balance (Cohen, 1988). SMDs on each potential confounder are compared between unweighted and inverse propensity score weighted samples.

In this example, because we had a latent multinomial exposure, to examine balance we used the BCH approach to estimate the within-class means/proportions for each potential confounder (one at a time) and calculated SMD = (difference in mean or proportion between 2 classes) / (overall standard deviation among all individuals). Table 4 shows the means/proportions on each potential confounder for each latent class, as well as the SMD for the two ATEs of interest (i.e., Enhancement versus Few Reasons and Coping versus Enhancement Reasons). Binge drinking (i.e., drank 5+ drinks in a row in past 2 weeks: 1=none, …, 6=10+ times) showed the poorest balance (SMD = .42 for Enhancement versus Few Reasons) prior to inverse propensity score weighting. As shown in Table 4, balance on the potential confounders across all latent classes (i.e., exposures) was substantially improved after applying the inverse propensity score weights; adequate balance was achieved on all potential confounders for the ATEs of interest.

Table 4.

Balance Table Showing Means/Proportions and Standardized Mean Differences on Potential Confounders

| Unweighted | Weighted | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Potential Confounder | Few Reasons |

Enhancement Reasons |

Coping Reasons |

Diverse Reasons |

SMD for Enhancement vs. Few ATE |

SMD for Coping vs. Enhancement ATE |

Few Reasons |

Enhancement Reasons |

Coping Reasons |

Diverse Reasons |

SMD for Enhancement vs. Few ATE |

SMD for Coping vs. Enhancement ATE |

| Cohort | 1986.33 | 1986.45 | 1987.18 | 1986.59 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 1986.59 | 1986.76 | 1986.94 | 1984.91 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Gender | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.73 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Race: Black | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.34 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Hispanic | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| Other | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Living in two-parent family | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Parents' highest level of education | 0.59 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.73 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Average grades in high school | 6.13 | 6.17 | 5.96 | 5.24 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 5.96 | 6.05 | 6.06 | 5.99 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Took college prep curriculum | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Definitely plans to graduate college | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| No. days cut school in past 30 | 1.51 | 1.88 | 1.84 | 2.27 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 1.79 | 1.78 | 1.77 | 1.73 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Importance of religion | 2.74 | 2.44 | 2.60 | 2.52 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 2.61 | 2.60 | 2.67 | 2.39 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Ave no. days per wk going out | 3.39 | 3.80 | 3.55 | 3.96 | 0.33 | 0.10 | 3.60 | 3.60 | 3.52 | 3.70 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Smoked cig in past 30 days | 1.55 | 1.74 | 1.95 | 2.29 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 1.82 | 1.78 | 1.71 | 1.90 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Drank 5+ drinks in past 2 wk | 1.47 | 2.00 | 1.87 | 2.53 | 0.42 | 0.08 | 1.81 | 1.85 | 1.82 | 1.85 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Used marijuana in past 12 mo | 1.42 | 2.06 | 1.76 | 2.52 | 0.35 | 0.16 | 1.83 | 1.84 | 1.73 | 1.83 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| Used other substances in past 12 mo | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

Notes. SMD = Standardized mean difference (absolute value) in potential confounder between two latent classes; SMDs > 0.20 are bolded to facilitate interpretation of large differences. ATE = Average exposure effect; the ATEs of interest were membership in the Enhancement Reasons versus Few Reasons and in the Coping Reasons versus Enhancement Reasons latent classes at age 19 on problem alcohol use vs. non-problem use/abstinence at age 35. Attrition weights adjusting for the Monitoring the Future study design and BCH weights adjusting for classification error were used in both the unweighted and weighted analysis.

Step 4. Conduct outcome analysis

After confirming that overlap is adequate and balance is achieved with the inverse propensity score weights, the weighted outcome analyses to obtain the estimated ATEs is conducted. Typically, the outcome analysis to address the causal research question of interest is straightforward and involves a weighted regression model for the outcome on dummy-coded exposure group membership. Robust standard errors of effect estimates are recommended to account for the fact that the inverse propensity score weights are estimated. In this example, one appropriate outcome analysis is a weighted logistic regression model for problem alcohol use (versus non-problem use or abstinence) on dummy-coded latent class membership with the Few Reasons latent class coded as the reference.

We again used the BCH approach to obtain the necessary parameter estimates for predicting problem alcohol use at age 35 from latent class membership at age 19. In this example, we estimated both an unweighted ATE and a weighted ATE. The unweighted ATE included the attrition weights to adjust for the MTF study design only; the weighted ATE included the final analysis weight calculated in Step 2 that combined the inverse propensity score weight with the MTF attrition weight. In both analyses the weights were treated as survey sample weights and robust standard errors were requested.

Table 5 shows the unweighted and weighted effects of reasons for alcohol use latent class membership at age 19 on problem alcohol use at age 35, adjusting for potential confounders assessed at age 18. Even after adjusting for confounding, there was a significant causal effect of membership in the Enhancement Reasons latent class compared to membership in the Few Reasons latent class at age 19 on the chances of having problem alcohol use vs. non-problem use/abstinence at age 35. If all individuals in the population had Enhancement Reasons for alcohol use at age 19, an estimated 38% of them would have problem alcohol use at age 35, whereas if all individuals had Few Reasons at age 19, an estimated 22% of them would have problem alcohol use at age 35. That is, having Enhancement Reasons corresponds to being 1.17 times (odds ratio = e0.16 = 1.17) more likely to have problem alcohol use compared to having Few Reasons. In comparison, those with Enhancement Reasons at age 19 were about equally likely to have problem alcohol use at age 35 as those with Coping Reasons (ATE = .07, p > .05).

Table 5.

Average Exposure Effects (ATEs) of Reasons for Alcohol Use Latent Class Membership at Age 19 on Problem Alcohol Use at Age 35

| Mean (SE) | ATE | SE | Odds Ratio |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Few Reasons | Enhancement Reasons | ||||

|

|

|||||

| Unweighted | 0.20 (0.01) | 0.41 (0.02) | 0.21 | 0.03 | 1.24 |

| Weighted | 0.22 (0.02) | 0.38 (0.02) | 0.16 | 0.03 | 1.17 |

|

| |||||

| Enhancement Reasons | Coping Reasons | ||||

|

|

|||||

| Unweighted | 0.41 (0.02) | 0.47 (0.03) | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.06 |

| Weighted | 0.38 (0.02) | 0.45 (0.04) | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.08 |

Notes. ATE = Average exposure effect; SE = Standard error. Bold font indicates a significant effect at α=0.05. The ATEs of interest were membership in the Enhancement Reasons versus Few Reasons and in the Coping Reasons versus Enhancement Reasons latent classes at age 19 on problem alcohol use vs. non-problem use/abstinence at age 35. Attrition weights adjusting for the Monitoring the Future study design and BCH weights adjusting for classification error were used in both the unweighted and weighted analysis.

Software note

We used Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 2015) to estimate the necessary models, and we used R (R Core Team, 2015) to perform necessary calculations, such as calculating P(T = t|xi) from Equation 2 and π̂i from Equation 3. However, other software packages may be used. For example, SAS PROC LCA (Lanza, Dziak, Huang, Wagner, & Collins, 2015) or Latent GOLD (Vermunt & Magidson, 2015) could have been used instead of Mplus, and MathWorks’ Matlab or Microsoft Excel could have been used instead of R. Annotated generic sample code for Mplus and R are available in the online supplementary appendix and at methodology.psu.edu/downloads/appendices/lc-causal-exposures.

Discussion

As prevention scientists continue to use LCA to identify population subgroups, many interesting research questions about the causal effects of latent class exposures may arise. The step-by-step empirical example presented here illustrates one approach to estimating these effects. In particular, we used data from the U.S. national MTF study to show that odds of problem alcohol use at age 35 would be about 17% higher if all individuals in the population had Enhancement Reasons for alcohol use at age 19 compared to if all individuals in the population had Few Reasons, but no significant differences were found between having Enhancement Reasons and Coping Reasons. That is, even after adjusting for a variety of characteristics, certain patterns of alcohol use reasons were significantly associated with elevated risk for problem alcohol use relative to other patterns. This provides evidence that alcohol use reasons are important risk factors for subsequent alcohol use problems and supports the idea that reasons for alcohol use represent important screening criteria and/or potential targets for prevention and intervention.

In our example, the unweighted and weighted results were quite similar. Although this was somewhat unexpected, effect estimates may increase, decrease, or stay the same after inverse propensity score weighting and this should not be seen as a reason to or not to use modern causal inference methods. Additionally, because of the similarities in results here, more straightforward approaches, such as traditional covariate adjustment may seem like attractive alternatives. A large body of literature has discussed the limitations of approaches where some number of potential confounders are added directly to the outcome analysis in order to control for them (e.g., Dehejia & Wahba, 2002; Rubin, 2001). Notably, propensity score approaches allow for the efficient, simultaneous adjustment of many more potential confounders than is typically possible with traditional covariate adjustment. In addition, an important advantage of using propensity score approaches over traditional covariate adjustment is their usefulness in recognizing and diagnosing issues with the assumptions of overlap and balance, critical to avoiding inappropriate extrapolation (Austin, 2011; Rubin, 1997; Schafer & Kang, 2008). An accessible discussion of the relative advantages and disadvantages of propensity score approaches and traditional covariate adjustment is available from Zanutto (2006).

The example presented here was intended primarily to demonstrate the approach and so the scope was somewhat narrow. For example, here we compared the effects of only three of the four identified latent classes. Also, additional potential confounders or additional effects of confounders (e.g., interactions between confounders) could have been added to the propensity score model to increase the strength of our causal inferences. In addition, our analyses focused on ATEs of membership in one latent class compared to another latent class. In the context of a latent multinomial exposure, an ATE focuses on the effect if everyone in the population belonged to one latent class (e.g., Enhancement Reasons) compared to a scenario in which everyone in the population belonged to another latent class (e.g., Few Reasons). However, there are a number of other causal effects that may be of interest, such as the average exposure effect among the exposed (ATT; i.e., average treatment effect among the treated; Austin, 2011). The form of the weights depends on the causal effect of interest (e.g., McCaffrey et al., 2014).

Some aspects of the proposed approach require further research. We used casewise deletion for missing data on the potential confounders for simplicity and because our missing data were minimal, but other approaches should be considered. For example, Mplus provides a way to include missing data on covariates using full information maximum likelihood, assuming they are continuous-normal (Muthén and Muthén, 2015). More generally, a straightforward alternative to listwise deletion is mean imputation (White & Thompson, 2004), which is commonly used for propensity score estimation. More sophisticated approaches such as multiple imputation (Schafer & Graham, 2002; van Buuren, 2007) could be considered, but would need to account for the necessary BCH weights. Additionally, how to use doubly robust methods (Bang and Robins, 2005; Kang & Schafer, 2007; Tan, 2010) is an open question.

Another topic for future research is the investigation of alternative approaches to estimating the propensity scores. We used multinomial logistic regression because (a) it is a natural extension of the commonly used logistic regression for binary exposures, (b) it is straightforward to implement with a latent class variable when the BCH approach is used, and (c) it is is readily available in LCA software. However, when exposures are observed, alternatives to logistic regression can be advantageous, such as generalized boosted models (see McCaffrey et al., 2013). Using these alternatives with a latent exposure may require modification, in order to take into account the fact that only the posterior probabilities of each individual’s class memberships are available, not the class memberships themselves. A related topic is whether the generalized propensity scores proposed here should be trimmed in cases where corresponding inverse propensity score weights are very large. In our simulation study, trimming the weights did not appear to improve the results when the BCH approach was used, and so we did not trim our weights in the current study. However, more work needs to be done in this area. Additionally, the newly proposed “overlap weights” (Li, Lock Morgan, & Zaslavsky, 2016) have favorable practical and theoretical properties, and should be investigated in this context.

In conclusion, the step-by-step approach presented in the current study can be used to estimate ATEs of latent class exposures in many areas of prevention science using LCA to understand population subgroups. Integrating inverse propensity score weighting with LCA with distal outcomes provides a rigorous way to adjust for potential confounders when investigating the effects of latent class membership on outcomes. As increasingly complex research questions are posed about the roles played by latent class variables in development and prevention, the integration of these two methods provides a new tool for the identification of causal mechanisms leading to negative outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Deborah D. Kloska for help with management of the Monitoring the Future data sets and Donna L. Coffman for early discussions that helped inform our thinking about causal latent class exposures.

Bethany C. Bray, The Methodology Center and College of Health and Human Development, Penn State, 404 Health & Human Development Bldg., University Park, PA, 16802; John J. Dziak, The Methodology Center, Penn State, 404 Health & Human Development Bldg., University Park, PA, 16802; Megan E. Patrick, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, 426 Thompson St., Ann Arbor, MI, 48106; Stephanie T. Lanza, The Methodology Center, Edna Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center, and Department of Biobehavioral Health, Penn State, 404 Health & Human Development Bldg., University Park, PA, 16802.

Funding. This research was conducted at The Pennsylvania State University and The University of Michigan, and was supported by a seed grant from the National Center for Responsible Gaming (NCRG) and awards P50-DA039838, P50-DA010075, and R01-DA037902 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA); data collection was supported by awards R01-DA001411 and R01-DA016575 from NIDA.

Footnotes

The earliest timeframe during which problem alchol use could be assessed with the MTF data was the last 5 years prior to age 35. If there were individuals who developed problem alcohol use and fully recovered by age 30, we were unable to identify them as positive cases.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical approval. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent. Where appropriate, informed consent and assent were obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NCRG, NIDA or the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling. 2014;21:329–341. [Google Scholar]

- Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2011;46:399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakk Z, Vermunt JK. Robustness of stepwise latent class modeling with continuous distal outcomes. Structural Equation Modeling. 2016;23:20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bang H, Robins JM. Doubly robust estimation in missing data and causal inference models. Biometrics. 2005;61:962–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolck A, Croon M, Hagenaars J. Estimating latent structure models with categorical variables: One-step versus three-step estimators. Political Analysis. 2004;12:3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bray BC, Almirall D, Zimmerman RS, Lynam D, Murphy SA. Assessing the total effect of time-varying predictors in prevention research. Prevention Science. 2006;7:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0023-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray BC, Lanza ST, Tan X. Eliminating bias in classify-analyze approaches for latent class analysis. Structural Equation Modeling. 2015;22:1–11. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.935265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso JB, Goldbach JT, Cervantes RC, Swank P. Stress and multiple substance use behaviors among Hispanic adolescents. Prevention Science. 2016;17:208–217. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0603-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman DL, Caldwell LL, Smith EA. Introducing the at-risk average causal effect with application to HealthWise South Africa. Prevention Science. 2012;13:437–447. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0271-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman D, Patrick ME, Palen L, Rhoades BL, Ventura A. Why do high school seniors drink? Implications for a targeted approach. Prevention Science. 2007;8:241–248. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman DL, Zhong W. Assessing mediation using marginal structural models in the presence of confounding and moderation. Psychological Methods. 2012;17:642–664. doi: 10.1037/a0029311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. New York: Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dehejia RH, Wahba S. Propensity score matching methods for non-experimental causal studies. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2002;84:151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Dziak JJ, Bray BC, Zhang J, Zhang M, Lanza ST. Comparing the performance of improved classify-analyze approaches for distal outcomes in latent profile analysis. Methodology. 2016;12:107–116. doi: 10.1027/1614-2241/a000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Polce RJ, Patrick ME, Miech R. Patterns of reasons for vaping in a national sample of adolescent vapers; Paper presented at the Society for Prevention Research 25th Annual Meeting: “Prevention and Public Systems of Care: Research, Policy and Practice,”; Washington, DC. 2017. May, [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Stuart EA. Examining moderation analyses in propensity score methods: Application to depression and substance use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82:773–783. doi: 10.1037/a0036515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilreath TD, Astor RA, Estrada JN, Jr, Benbenishty R, Unger JB. School victimization and substance use among adolescents in California. Prevention Science. 2014;15:897–906. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0449-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Héroux M, Janssen I, Lee DC, Sui X, Hebert JR, Blair SN. Clustering of unhealthy behaviors in the aerobics center longitudinal study. Prevention Science. 2012;13:183–195. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0255-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbens G. The role of the propensity score in estimating dose-response functions (Tech. Work. Paper No. 237) Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 1999. Retreived from https://www.nber.org/papers/t0237.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Beals J, Zhang L, Mitchell CM, Manson SM, Acton KJ. Special Diabetes Program for Indians Demonstration Projects. Latent class analysis of stages of change for multiple health behaviors: Results from the Special Diabetes Program for Indians diabetes prevention program. Prevention Science. 2012;13:449–461. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0272-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2015: Volume 2, college students and adults ages 19–55. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kang JDY, Schafer JL. Demystifying double robustness: A comparison of alternative strategies for estimating a population mean from incomplete data (with discussion and rejoinder) Statistical Science. 2007;22:523–539. doi: 10.1214/07-STS227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Bray BC, Collins LM. An introduction to latent class and latent transition analysis. In: Schinka JA, Velicer WF, Weiner IB, editors. Handbook of psychology. 2. Vol. 2. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2013. pp. 691–716. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Coffman DL, Xu S. Causal inference in latent class analysis. Structural Equation Modeling. 2013;20:361–383. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2013.797816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Dziak JJ, Huang L, Wagner A, Collins LM. PROC LCA & PROC LTA users' guide (Version 1.3.2) University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State; 2015. Retrieved from http://methodology.psu.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Moore JE, Butera NM. Drawing causal inferences using propensity scores: A practical guide for community psychologists. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;52:380–392. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9604-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Rhoades BL. Latent class analysis: An alternative perspective on subgroup analysis in prevention and treatment. Prevention Science. 2013;14:157–168. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0201-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Schuler MS, Bray BC. Latent class analysis with causal inference: The effect of adolescent depression on young adult substance use profile. In: Wiedermann W, von Eye A, editors. Causality and Statistics. Chp. 16. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2016. pp. 385–404. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Tan X, Bray BC. Latent class analysis with distal outcomes: A flexible model-based approach. Structural Equation Modeling. 2013;20:1–26. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2013.742377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Lock Morgan K, Zaslavsky AM. Balancing covariates via propensity score weighting. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2016 doi: 10.1080/01621459.2016.1260466. Advance online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Low S, Smolkowski K, Cook C. What constitutes high-quality implementation of SEL programs? A latent class analysis of Second Step® implementation. Prevention Science. 2016;17:981–991. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0670-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunceford JK, Davidian M. Stratification and weighting via the propensity score in estimation of causal treatment effects: a comparative study. Statistics in Medicine. 2004;23:2937–2960. doi: 10.1002/sim.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey DF, Griffin BA, Almirall D, Slaughter ME, Ramchand R, Burgette LF. A tutorial on propensity score estimation for multiple treatments using generalized boosted models. Statistics in Medicine. 2013;32:3388–3414. doi: 10.1002/sim.5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Wardell JD, Read JP. Drinking motives in the prospective prediction of unique alcohol-related consequences in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:93–102. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2016: Volume I, secondary school students. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Bray BC, Berglund P. Reasons for marijuana use among young adults and long-term associations with marijuana use and problems. Journal on Studies of Alcohol and Drugs. 2016;77:881–888. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Evans-Polce R, Kloska DD, Maggs JL, Lanza ST. Age-related changes in associations between reasons for alcohol use and high-intensity drinking across young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.558. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. How trajectories of reasons for alcohol use relate to trajectories of binge drinking: National panel data spanning late adolescence to early adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:311–317. doi: 10.1037/a0021939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Johnston L, Bachman J. Adolescents’ reported reasons for alcohol and marijuana use as predictors of substance use and problems in adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:106–116. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. Retreived from http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway G, Kovalchik SA, Griffin BA, Kabeto MU. Propensity score analysis with survey weighted data. Journal of Causal Inference. 2015;3:237–249. doi: 10.1515/jci-2014-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM, Hérnan MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11:550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;127:757–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: Application to the tobacco litigation. Health Services & Outcomes Research Methodology. 2001;2:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Kang J. Average causal effects from nonrandomized studies: A practical guide and simulated example. Psychological Methods. 2008;13:279–313. doi: 10.1037/a0014268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2016: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19–55. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME, Kloska DD, Maslowsky J, Maggs JL, O'Malley PM. Substance use disorder in early midlife: A national prospective study on health and well-being correlates and long-term predictors. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment. 2015;9(Suppl 1):41–57. doi: 10.4137/SART.S31437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MS. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 2013. Estimating the relative treatment effects of natural clusters of adolescent substance abuse treatment services: Combining latent class analysis and propensity score methods. Retrieved from https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/36988/SCHULER-DISSERTATION-2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MS, Leoutsakos JS, Stuart EA. Addressing confounding when estimating the effects of latent classes on a distal outcome. Health Services Outcomes and Research Methodology. 2014;14:232–254. doi: 10.1007/s10742-014-0122-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilt JL, Koot JM, van Lier PA. For whom does it work? Subgroup differences in the effects of a school-based universal prevention program. Prevention Science. 2013;14:479–488. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0329-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapinski LA, Edwards AC, Hickman M, Araya R, Teesson M, Newton NC, Heron J. Drinking to cope: A latent class analysis of coping motives for alcohol use in a large cohort of adolescents. Prevention Science. 2016;17:584–594. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0652-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton JL, Turrisi R, Cleveland MJ, Ray AE, Lu SE. Pre-college matriculation risk profiles and alcohol consumption patterns during the first semesters of college. Prevention Science. 2014;15:705–715. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0426-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Z. Bounded, efficient and doubly robust estimation with inverse weighting. Biometrika. 2010;97:661–682. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2007;16:219–242. doi: 10.1177/0962280206074463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varvil-Weld L, Crowley DM, Turrisi R, Greenberg MT, Mallett KA. Hurting, helping, or neutral? The effects of parental permissiveness toward adolescent drinking on college student alcohol use and problems. Prevention Science. 2014;15:716–724. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0430-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK. Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis. 2010;18:450–469. [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK, Magidson J. Upgrade manual for Latent GOLD 5.1. Belmont, MA: Statistical Innovations; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- White IR, Thompson SG. Adjusting for partially missing baseline measurements in randomized trials. Statistics in Medicine. 2005;24:993–1007. doi: 10.1002/sim.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K. Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry Discussion Paper Series (No. 15-E-090) Tokyo, Japan: The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry; 2015. Extensions of Rubin's causal model for a latent-class treatment variable: An analysis of the effects of employers' work-life balance policies on women's income attainment in Japan. Retrieved from http://www.rieti.go.jp/jp/publications/dp/15e090.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Zanutto EL. A comparison of propensity score and linear regression analysis of complex survey data. Journal of Data Science. 2006;4:67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Liu W, Zhang B, Tang L, Zhang J. Causal inference with missing exposure information: Methods and applications to an obstetric study. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2016;25:2053–2066. doi: 10.1177/0962280213513758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.