Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the principal antigen-presenting cells of the immune system and play key roles in controlling immune tolerance and activation. As such, DCs are chief mediators of tumor immunity. DCs can regulate tolerogenic immune responses that facilitate unchecked tumor growth. Importantly, however, DCs also mediate immune-stimulatory activity that restrains tumor progression. For instance, emerging evidence indicates the cDC1 subset has important functions in delivering tumor antigens to lymph nodes and inducing antigen-specific lymphocyte responses to tumors. Moreover, DCs control specific therapeutic responses in cancer including those resulting from immune checkpoint blockade. DC generation and function is influenced profoundly by cytokines, as well as their intracellular signaling proteins including STAT transcription factors. Regardless, our understanding of DC regulation in the cytokine-rich tumor microenvironment is still developing and must be better defined to advance cancer treatment. Here, we review literature focused on the molecular control of DCs, with a particular emphasis on cytokine- and STAT-mediated DC regulation. In addition, we highlight recent studies that delineate the importance of DCs in anti-tumor immunity and immune therapy, with the overall goal of improving knowledge of tumor-associated factors and intrinsic DC signaling cascades that influence DC function in cancer.

Keywords: Dendritic cell, tumor, cytokine, STAT, molecular regulation, antigen presentation

1. Introduction

Similar to other immune lineages, fully differentiated DCs comprise distinct subsets that differ in function, morphology, and anatomical location. DC subsets arise from specified hematopoietic progenitors, and require unique transcriptional and signaling programs for their development and functional responses. In some cases, DC transcriptional and signaling responses are activated or repressed by extracellular factors in the tumor microenvironment (TME), such as cytokines, which influence DC function. Furthermore, recent work indicates the importance of specific DC populations such as cDC1s in tumor immunity and immune therapy. Nonetheless, the potential for DC use in cancer treatment remains largely untapped. Improved understanding of DC regulation during development and in the TME is necessary for generating novel cancer therapies and effectively reducing the burden of this devastating disease. Towards this aim, we review molecular mechanisms controlling DCs, with a specific focus on cytokines and cytokine-activated STATs, as well as roles for specific DC subsets in cancer and cancer therapy.

2. Dendritic cell subsets and their developmental regulation

2.1. DC subsets and cross species identification

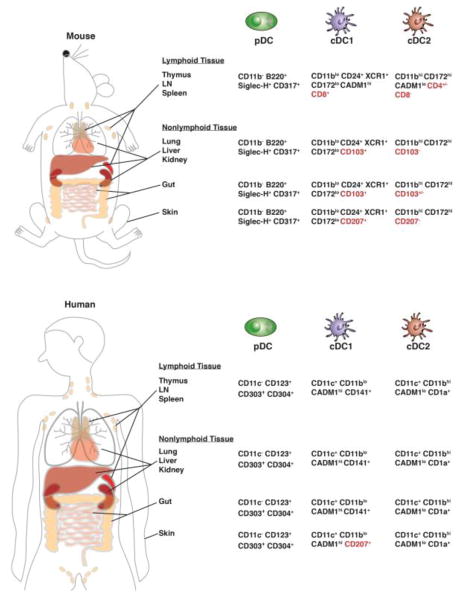

In steady state conditions, DCs are customarily divided into two major populations, the conventional or classical DC (cDC) subsets and the plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) (Fig. 1). Traditionally, the cDCs are recognized as the professional antigen-presenting cells, while pDCs are major producers of type I interferons (IFN-Is). Moreover, the cDC subsets comprise type 1 cDCs (cDC1s) and type 2 cDCs (cDC2s), which also differ in function, localization, and morphology. Canonical surface marker (phenotypic) profiles of major murine and human DC subsets are delineated in Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Fig. 1. Identification and localization of mouse and human DC subsets.

The major DC populations in lymphoid and non-lymphoid organs of mouse and human are indicated by cross species markers recently identified by (Guilliams et al., 2016). Tissue-specific DC markers are highlighted in red.

Table 1.

Phenotypic markers and transcriptional regulators of murine and human DC subsets.

denotes negative regulators

Recently, an unsupervised high-dimensional clustering analysis based on marker expression revealed that cDC1s can be defined across species as CADM1hi XCR1hi CD11blo CD172lo CD24hi cells, while cDC2s can be defined as CADM1lo XCR1lo CD11bhi CD172hi cells (Guilliams et al., 2016). This information is valuable in standardizing DC definitions and should be taken into account when analyzing DCs. Since DC subsets demonstrate unique functions, their accurate identification is important for understanding DC roles in immune responses, cancer and other diseases. In this review, we will refer to unique DC subsets (e.g., cDC1, cDC2, pDC) when these were defined in the experiments under discussion, while our use of the term “DC” will indicate information relevant to most DC populations or when specific subsets were not delineated experimentally.

2.2. DC subsets in inflammation

Inflammatory conditions have profound effects on DCs. In some cases, this has led to confusion or disparate definitions of DC populations. Furthermore, inflammation itself is a broad term, referring to distinct states such as type I or type II inflammation that are characterized by specific cytokines and immune responses (Turner et al., 2014; Wynn, 2015). Thus, descriptions of DCs in inflammation must consider the effects of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators on characteristic DC markers, as well as DC migration, tissue retention or survival. For example, inflammatory conditions associated with infection or abundant amounts of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) elicit rapid production of monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs, CD11c+ CD11b+ Ly6C+ MHC II+) (Cook et al., 2004; Dominguez and Ardavin, 2010; Greter et al., 2012; Leon and Ardavin, 2008; Rothchild et al., 2014; Serbina et al., 2003). In murine models of inflammatory arthritis and peritonitis, MoDC differentiation is dependent on GM-CSF derived from CD4+ T cells (Campbell et al., 2011). One type of MoDCs expresses tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and iNOS (also termed Tip-DC), and contributes to immune responses as well as pathological inflammatory reactions (Bosschaerts et al., 2010; Guilliams et al., 2014; Mildner and Jung, 2014; Serbina et al., 2003). The effects of inflammation on DCs will be further considered in our discussion of tumor influences on DCs.

2.3. DC development from hematopoietic progenitors

The majority of DC populations originate from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) via multipotent and lineage-restricted progenitor subsets including common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) and common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) (D’Amico and Wu, 2003) (Chicha et al., 2004; Karsunky et al., 2003). A classic view of the DC developmental path involves the sequential generation of macrophage/DC progenitors (MDPs), common DC progenitors (CDPs), and pre-DCs, which arise primarily from CMPs and granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs) (Naik et al., 2007) (Fogg et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2009; See et al., 2017). Separately, early lymphoid-primed progenitors have been reported to possess potential to differentiate into cDCs, which are phenotypically indistinguishable from MDP-derived DCs (Helft et al., 2017; Naik et al., 2013), suggesting a dual ontogeny of cDCs.

Additional studies revealed two subsets of DC-committed progenitors based on the differential expression of CD115. The CD115− (lin− Flt3+ CD117int CD115−) DC progenitors are biased toward pDC differentiation, while CD115+ (lin− Flt3+ CD117int CD115+) CDPs give rise mainly to cDC1s and cDC2s (Onai et al., 2013). Recent work has shown pre-DCs can be divided into four subpopulations on the basis of Siglec-H and Ly6C expression. Siglec-H+ Ly6C− pre-DCs retain pDC developmental potential, while Siglec-H+ Ly6C+ pre-DCs selectively produce precursor subsets with restricted ability to generate cDC1 or cDC2 lineages. The Siglec-H− Ly6C− CD24+ pre-DCs are committed to cDC1s and Siglec-H− Ly6C+ CD24− pre-DCs are primed toward cDC2s (Schlitzer et al., 2015). By contrast, Langerhans cells as well as tissue-resident macrophages develop from embryonic precursors including erythromyeloid progenitor cells or monocytes residing in yolk sac or fetal liver, respectively (Hoeffel et al., 2012). The HSC-derived and embryonic developmental pathways have been reviewed previously and we refer readers to the following excellent resources for additional information (Ginhoux and Merad, 2010; Mildner and Jung, 2014; Murphy et al., 2016; Swiecki and Colonna, 2015).

2.4. Transcriptional regulation of DC development by intrinsic factors

Numerous transcriptional regulators mediate development of DCs from HSCs and specified hematopoietic progenitors (Table 1). Certain factors including PU.1, GATA-2, Ikaros, and Gfi1 are necessary for both pDC and cDC development, due to their essential activity in early hematopoietic progenitor subsets (Anderson et al., 2000; Carotta et al., 2010; Guerriero et al., 2000; Iwama et al., 2002; Li et al., 2016a; Onodera et al., 2016; Rathinam et al., 2005; Wu et al., 1997). Other transcriptional regulators play specific roles in one or more DC lineages. For instance, IRF8, ID2, and Batf3 are the principal factors controlling cDC1 generation (Edelson et al., 2010; Hacker et al., 2003; Hildner et al., 2008; Poulin et al., 2012; Schiavoni et al., 2002; Sichien et al., 2016; Tamura et al., 2005; Tsujimura et al., 2003), whereas IRF2, IRF4, and RelB mediate cDC2 differentiation (Ichikawa et al., 2004; Schlitzer et al., 2013; Suzuki et al., 2004; Tamura et al., 2005; Watchmaker et al., 2014; Wu et al., 1998), and E2-2 is uniquely required for the pDC lineage (Cisse et al., 2008) (Table 1). Mutations in several key DC factors, including IRF8, GATA-2, and E2-2, abrogate development of DCs as well as other immune subsets (e.g., macrophages) in humans (Bigley et al., 2016; Cisse et al., 2008; Dickinson et al., 2011; Hambleton et al., 2011). This research not only underscores crucial, conserved roles for specific transcriptional regulators and the affected DC populations in immunity, but also provides opportunities to understand cross-species transcriptional pathways that are necessary for DC development.

2.5. Transcriptional regulation of DC development by cytokines and STATs

By contrast with the previously described transcriptional regulators, STAT transcription factors are activated in DCs and their progenitors by extracellular cytokines, which are expressed in hematopoietic tissues such as bone marrow, and are often found in abundance in tumors, or produced systemically during infection or inflammation (Diao et al., 2010; Sere et al., 2013; Turner et al., 2014; Vega-Ramos et al., 2014a; Vega-Ramos et al., 2014b; Yang and Lattime, 2003; Yang et al., 2003). Cytokines associate with unique high affinity cell surface receptors, which activates rapid signal transduction to the nucleus via the Jak-STAT pathway, culminating in transcriptional responses that elicit significant effects on cellular behavior (Schindler et al., 2007). The Jak-STAT pathway is stimulated by ligand-induced receptor conformational changes that activate associated Jak protein tyrosine kinases, which subsequently phosphorylate residues within the receptor intracellular domain. This enables recruitment of STAT proteins to the receptor-Jak complex, and results in STAT phosphorylation by Jaks. Tyrosine phosphorylation of STATs stimulates their homo- or heterodimerization, nuclear accumulation, and STAT-mediated transcriptional regulation (Schindler et al., 2007). A total of seven STAT proteins have been identified (STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5a, STAT5b, STAT6); each is responsive to an array of cytokines (Li and Watowich, 2014; Stark and Darnell, 2012).

STATs have been shown to play key roles in DC development in homeostasis and cytokine-driven conditions (Chen et al., 2013; Durai and Murphy, 2016; Fancke et al., 2008; Hillmer et al., 2016; Karsunky et al., 2003; Li and Watowich, 2013; Murphy et al., 2016; Onai and Manz, 2008; Sere et al., 2013; van de Laar et al., 2012) (Table 1). For instance, STAT3 is stimulated in hematopoietic progenitors by FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3L) (Esashi et al., 2008), which is essential for development of all HSC-derived DC populations (Gilliet et al., 2002; Kingston et al., 2009; Maraskovsky et al., 1996; McKenna et al., 2000; Naik et al., 2005). STAT3 deletion from hematopoietic cells abrogates Flt3L-induced progenitor proliferation, as well as expansion of cDCs and pDCs in response to Flt3L administration (Esashi et al., 2008; Laouar et al., 2003; Li et al., 2012). An initial report indicated STAT3 deletion led to reduction of all DC subsets in homeostatic conditions (as judged by analysis of CD11c+ cells); however, subsequent studies showed STAT3 was specifically required for pDC generation but not cDC production in steady state (Laouar et al., 2003; Li et al., 2012; Melillo et al., 2010). STAT3 stimulates Flt3L-responsive expression of the pDC transcriptional regulator E2-2 in CDPs, suggesting a molecular pathway by which STAT3 selectively regulates pDC generation (Li et al., 2012). Recently, a STAT3-binding long noncoding RNA (lnc-DC) was identified as a positive regulator of human MoDC and murine cDC differentiation (Wang et al., 2014). Lnc-DC prevents the dephosphorylation of STAT3 on tyrosine 705 (Y705), which promotes sustained STAT3 activity via persistent Y705 phosphorylation (Wang et al., 2014), a post-translational modification that is required for canonical STAT3 transcriptional function (Hillmer et al., 2016). While a requirement for lnc-DC-mediated STAT3 activation in murine cDC differentiation was somewhat unexpected in light of the dispensable role for STAT3 in cDCs determined by genetic STAT3 ablation (Li et al., 2012; Melillo et al., 2010), additional work is required to fully understand cDC1, cDC2, and MoDC regulation by lnc-DC and STAT3 in vivo.

STAT5 is stimulated by GM-CSF, the cytokine used originally to generate DCs from murine bone marrow or human peripheral blood cultures (Caux et al., 1996; Inaba et al., 1992; Sallusto and Lanzavecchia, 1994). It is now recognized that GM-CSF induces production of several DC populations as well as MoDCs in culture, although the relationship of these subsets to DC and monocyte populations found in vivo remains uncertain (Helft et al., 2015). Nonetheless, these data are consistent with earlier reports that showed limited roles for GM-CSF in homeostatic DC production in vivo (Kingston et al., 2009; Vremec et al., 1997). Intriguingly, GM-CSF is required for the generation of nonlymphoid organ cDC1 subsets, yet does not control other DC populations appreciably in steady state (Bogunovic et al., 2009; Greter et al., 2012; Kingston et al., 2009). GM-CSF overexpression leads to increases in nonlymphoid organ and lymphoid cDC1s, as well as cDC2s (Daro et al., 2000; Li et al., 2012; O’Keeffe et al., 2002). Interestingly, GM-CSF also has the unique function of inhibiting pDC production in vivo, as well as in Flt3L-containing cultures in vitro (Gilliet et al., 2002; Li et al., 2012; Zhan et al., 2012).

The majority of GM-CSF-mediated effects on DCs have been shown to require STAT5. For example, STAT5 stimulates ID2 expression in CDPs to promote generation of nonlymphoid organ cDC1s, which are uniquely dependent on STAT5 and GM-CSF (Greter et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012). STAT5 was also reported to inhibit IRF8 expression in DC progenitors, thereby blocking pDC generation (Esashi et al., 2008). New information regarding the nonhematopoietic role for IRF8 in pDC development as well as the recognition that STAT5 induces expression of ID2, a negative regulator of pDCs (Hacker et al., 2003; Li et al., 2012; Sichien et al., 2016), suggests suppression of pDC generation by GM-CSF-STAT5 signaling may be influenced significantly by the ability of STAT5 to mediate ID2 upregulation, although this hypothesis requires direct examination in vivo. Furthermore, the level and timing of STAT5 activation may be crucial in controlling DC development, as low STAT5 activity is reported to induce cDC commitment from human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors whereas high STAT5 activity inhibits the generation of pre-DCs from CD34+ progenitors but promotes terminal differentiation of cDCs from pre-DCs (van de Laar et al., 2011). Future work is needed to determine STAT5 function in DC progenitor subsets, cDC1 maintenance in tissues, and direct gene targets of STAT5 in progenitors and fully differentiated cDC1s.

The IFN-Is, including IFN-α and IFN-β, are important for mediating global antiviral responses and anti-tumor immunity. One component of the IFN-I-activated response involves control of DC production, particularly during infection or inflammation (Li et al., 2011). This is executed by the transcriptional regulators STAT1 and STAT2, which are the principal effectors of IFN-Is (Au-Yeung et al., 2013; Schindler et al., 2007). For example, STAT1 mediates IFN-α-induced production of pDCs, as well as the development and function of pDCs within Peyer’s patches, an intestinal secondary lymphoid organ (Li et al., 2011). A recent study indicates IFN-I works in collaboration with Flt3L to promote pDCs from the CLP subset (Chen et al., 2013). By contrast, IFN-β-STAT2 signals regulate CD8α + cDC development independent of STAT1 function (Hahm et al., 2005). Since IFN-I function in DCs are a major focus of the accompanying review by Vatner and Janssen, we refer readers to their publication for additional details. In addition, it is important to point out that other cytokines, such as macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), contribute to DC development via STAT-independent mechanisms (Borkowski et al., 1996; Fancke et al., 2008; Kaplan et al., 2007).

3. DC functions in immune activation and tolerance

3.1. DC activation and antigen presentation

DCs are the principal immune population bridging the innate and adaptive immune systems. This is due to their ability to recognize a variety of microbial-, pathogen-, and danger-associated molecular patterns (i.e., MAMPs, PAMPs, and DAMPs) via an “innate” response, and subsequently undergo maturation or activation events that promote their antigen-presenting functions and enable their regulation of antigen-specific adaptive immune responses. DC activation by MAMPs, PAMPs, and DAMPs is mediated by numerous cell surface and intracellular sensors, including the Toll-like receptors (TLRs). Significantly, TLR expression is a defining feature of specific DC subsets (Table 1). These unique TLR expression patterns endow DC subsets with specificity toward certain pathogens or danger signals, e.g., pDCs are highly responsive to infection with RNA- or DNA-containing viruses, which trigger TLR7 or TLR9 via the respective viral genomic material. By contrast, cDC1s detect intracellular pathogens, viruses, and tumor DAMPs through TLR3 (Edwards et al., 2003; Mashayekhi et al., 2011), while cDC2s recognize bacterial, parasite, and fungal PAMPs such as flagellin (TLR5 agonist) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS; TLR4 agonist) (Edwards et al., 2003).

Within hours of TLR ligation, DCs produce distinctive pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines that elicit STAT-signaling in responding populations through paracrine mechanisms. TLR3 stimulation of murine cDC1s favors secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-12 (IL-12) (Gauzzi et al., 2010; Hochrein et al., 2001; Maldonado-Lopez et al., 1999), which induces generation of the T helper 1 (Th1) subset from naïve CD4+ T cells via intrinsic STAT4 signaling (Pulendran et al., 1999; Zhu et al., 2010). By contrast, both human and murine pDC lineages are characterized by their ability to produce abundant amounts of IFN-Is, in addition to other pro-inflammatory factors, upon TLR7 or TLR9 stimulation (Heath and Carbone, 2009; Liu, 2005). This response contributes to activation of immune subsets such as cDCs via IFN-α/β-mediated stimulation (McKenna et al., 2005; Montoya et al., 2002). Moreover, cytokine production by both murine and human DCs activates innate immune populations including natural killer (NK) and innate lymphoid (ILCs) cells (Durai and Murphy, 2016; Lewis et al., 2011; Mashayekhi et al., 2011; Sabado et al., 2017; Tussiwand et al., 2015). Interestingly, recent studies show TLR ligation also alters DC metabolism in mouse and human DCs by increasing glycolytic flux, suggesting glycolysis is important for DC activation (Everts et al., 2014; O’Neill and Pearce, 2016).

In addition to cytokine production, key steps in DC activation include induction of MHC II, co-stimulatory molecules (e.g., CD80, CD86, CD40), and chemokine receptor expression (e.g., CCR2, CCR5, CCR7) (Akira et al., 2001; Blanco et al., 2008). Activation of cDC1s in peripheral tissues promotes their migration to lymph nodes (LNs). Both cDC1s and cDC2s capture and efficiently present peptides derived from “exogenous” (e.g., extracellular) antigens on MHC II molecules to activate CD4+ T cells, while “endogenous” (e.g., cytoplasmic) antigens are presented on MHC I molecules to activate CD8+ T cells (Neefjes et al., 2011). Furthermore, cDC1s possess enhanced ability to “cross-present” exogenous cell-associated antigens on MHC I molecules relative to other subsets, which enables cDC1s to stimulate potent cytotoxic CD8+ T cell responses to extracellular antigens such as those derived from tumors (Heath et al., 2004). In fact, the cDC1-mediated antigen cross-presentation pathway is crucial for CD8+ T cell priming, reactivation of memory CD8+ T cells, and anti-tumor CD8+ T cell responses (Hildner et al., 2008; Vyas et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2016). Intrinsic GM-CSF signaling was shown to be required for optimal cDC1 antigen cross-presentation activity, independent of DC growth (Zhan et al., 2011). DC-mediated antigen presentation provides the initial signal (i.e., signal 1) for naïve T cell activation. DC-expressed costimulatory molecules provide “signal 2”, while DC-produced cytokines comprise “signal 3”, culminating in the ability of DCs to shape adaptive immune responses according to the pathogen or danger signal sensed (Chen and Flies, 2013; Lichtman, 2012).

3.2. DC-mediated immune tolerance

In homeostatic conditions, most lymphoid organ DCs exhibit an immature phenotype, with low levels of MHC II and co-stimulatory molecules, which is crucial for DCs to mediate central and peripheral immune tolerance (Wilson et al., 2003). DCs in the medullary region of the thymus continuously sample and present self-antigens to developing T cells, which promotes development of natural regulatory T cells (nTreg) and contributes significantly to negative selection of CD4+ T cells with strong self-reactivity (Baba et al., 2009; Hadeiba and Butcher, 2013; Oh and Shin, 2015; Proietto et al., 2008). Notably, the thymic Sirpα+ cDC2s have been shown to play key roles in nTreg induction and negative selection in animal models (Baba et al., 2009; Proietto et al., 2008). Ginhoux and colleagues demonstrated recently that human fetal cDC2s promote enhanced Treg induction upon coculture with allogenic splenic T cells, while concomitantly suppressing CD8+ T cell proliferation and production of proinflammatory cytokines, in comparison to adult cDC2s (McGovern et al., 2017). Several mechanisms have been suggested to be involved in DC-mediated central tolerance, including modulation of costimulatory molecule expression (CD70, CD80, CD86) and induction of the metabolic enzyme arginase II (Coquet et al., 2013; Hanabuchi et al., 2010; McGovern et al., 2017; Watanabe et al., 2005). In addition, thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), a cytokine that signals through STAT5, was shown to activate human pDCs and cDCs, which in turn demonstrate efficient Treg generation due to impaired IL-12 production (Bell et al., 2013; Hanabuchi et al., 2010).

DC-deficiency in Flt3−/− mice or animals with conditional DC deletion due to lineage-specific expression of diptheria toxin receptor (DTR) (i.e., in Itgax-DTR animals) leads to a systemic reduction in nTregs and total Tregs, whereas mice with expanded cDC populations following Flt3L treatment show increased nTreg and total Treg amounts (Darrasse-Jèze et al., 2009). These data further link DCs with Treg abundance in vivo. Interestingly, the enrichment of nTregs specific for peripheral tissue, i.e. prostate, was shown to be dependent on active antigen presentation by DCs, as reduction of antigen load through castration or depletion of MHC II+ DCs caused marked reduction of nTregs in the prostate-draining LN (Leventhal, Immunity 2016). This process also required CCR7, consistent with earlier reports that induction of Treg proliferation in the periphery involves CCR7-mediated cDC1 trafficking to the LN (Idoyaga et al., 2013; Leventhal et al., 2016). Moreover, CX3CR1+ cDCs are required for induction of peripheral Tregs in response to orally fed antigens (Esterhazy et al., 2016). Similarly, intestinal CD103+ cDC1s are important in inducing gut-homing Tregs via their production of retinoic acid, TFG-β, and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) (Scott et al., 2011). More recently, Roquilly et al. reported that the function of DCs is severely restrained in mice recovering from primary pneumonia. In these conditions, DCs secrete elevated amounts of TGF-β and are biased to promote Treg differentiation (Roquilly et al., 2017). These findings are consistent with earlier reports that indicated DCs that had previously encountered inflammatory signals alter cytokine production (Vega-Ramos et al., 2014b).

Several anti-inflammatory molecules, including IL-10, TGF-β, and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), have been reported to inhibit DC activation, rendering DCs tolerogenic and enhancing their ability to induce peripheral Treg development. In addition to promoting Treg generation, DCs can also directly suppress effector T cells. For instance, DCs engage T cell co-inhibitory molecules including CD152 (CTLA-4) via DC-expressed CD80 or CD86, or CD279 (PD-1) via DC-expressed CD273 (PD-L2) or CD274 (PD-L1); these interactions repress T cell activation and limit T cell-mediated immunity (Butte et al., 2007). Overall, DCs actively promote tolerance towards self-antigens in the steady state through positive regulation of Tregs and via inhibition of effector T cells. Abrogating DC tolerance in the TME is likely to be central to improving tumor immunity, thus further understanding of DC tolerance mechanisms is critical.

3.3 STAT-mediated control of DC function

STAT1 and STAT2 are important mediators of DC activation, in particular DC responses to IFN-Is (Fuertes et al., 2011; Jackson et al., 2004; Johnson and Scott, 2007; Xu et al., 2016). For instance, STAT1 is required for optimal expression of MHC and costimulatory molecules in cDCs (Jackson et al., 2004; Johnson and Scott, 2007). Moreover, STAT1-deficiency reduces DC-mediated Th1 cell priming during infection such as Leishmania major (Jackson et al., 2004; Johnson and Scott, 2007). STAT1 is also important in activating pDCs, as STAT1-deficient pDCs produce less IFN-α, IL-12, and free radicals versus STAT1-sufficient pDCs, and express a tolerogenic phenotype, which attenuates the severity of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) (Capitini et al., 2014). Similar to STAT1, STAT2 is involved in DC activation upon TLR stimulation, including induction of IFN-I gene expression, cross-presentation of tumor antigens to CD8+ T cells, and antiviral responses (Chen et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2016).

By contrast with the activating functions of STAT1 and STAT2, STAT3 is regarded as a potent negative regulator of DCs. Cytokines that stimulate STAT3 in DCs, such as IL-10, inhibit DC-mediated production of pro-inflammatory factors, including IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-12, and thereby suppress DC-dependent immune and inflammatory responses. Accordingly, STAT3-deficient DCs have increased cytokine production and Th1 activation abilities following TLR stimulation, and animals with DC-specific or hematopoietic-restricted STAT3-deficiency develop chronic inflammatory bowel disease (Melillo et al., 2010). Furthermore, STAT3 induces expression of repressive factors in DCs, including cell surface expression of the co-inhibitory ligand PD-L1, which inhibits T cell activity (Hillmer et al., 2016).

STAT5 was originally reported to be important for DC activation by thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP). Mice with DC-restricted STAT5-deficiency showed reduced expression of co-stimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86, OX40L) and less CCL17 production from skin and lung DC populations. Moreover, STAT5 expression in DCs is critical in promoting T helper 2 (Th2) responses during airway inflammation (Bell et al., 2013). Mice with DC-specific deletion of STAT5 also exhibit reduced ear swelling and less DCs in the skin-draining LN during Th2 contact-hypersensitivity reactions (Bell et al., 2013). Consistently, STAT5 inhibition by the bromodomain inhibitor JQ1 disrupts human MoDC activation, as judged by defective CD83 upregulation, reduced IL-12 p70 production, and decreased Th1 polarization (Toniolo et al., 2015); however, these data must be interpreted with caution due to the potential for JQ1 to exert additional effects on gene expression and cellular responses.

Interestingly, STAT4 is induced by Th1 cytokines and LPS, and is required for IFN-γ production by DCs. By contrast, Th2 cytokines activate STAT6 while suppressing STAT4 in mouse and human DCs (Frucht et al., 2000; Fukao et al., 2001). Overall, however, STAT4 and STAT6 have been relatively understudied in DCs compared to other STATs. Future work directed toward delineating the function of these factors in DC-mediated immunity, as well as deeper insight into the mechanisms by which STAT-mediated gene expression regulates DC function, is necessary for understanding how DCs integrate cytokine signals in homeostasis, as well as during active immune responses or in the TME.

4. Cytokines in the TME and effects on DC function

4.1. DC growth factors and the TME

Several DC growth factors have important roles in mediating immune responses to tumors, although it is important to point out that certain growth factors also stimulate additional immune subsets as discussed below. Pioneering work in this area was done using B16 melanoma cells transduced with virus encoding GM-CSF, which caused GM-CSF secretion from the engineered tumor cells. Since GM-CSF was originally identified as a principal DC growth factor, this approach was used to increase DC migration and accumulation within tumors. GM-CSF transduction facilitated tumor rejection by the immune system, and protected mice from rechallenge with melanoma (Dranoff et al., 1993). This finding led to the development of cancer vaccines consisting of irradiated cancer cells transduced with GM-CSF, although unfortunately this vaccine strategy showed limited therapeutic effect in clinical trials (Lawson et al., 2015). This unanticipated poor response may be due to the lack of DC activating signals (e.g., TLR agonists), or high amounts of immunosuppressive factors in the TME following vaccination. In addition, GM-CSF is well recognized and in fact was originally identified as a myeloid growth factor capable of stimulating monocyte and granulocyte production from hematopoietic progenitor cells (Burgess et al., 1977; Burgess and Metcalf, 1980). Immature monocytes, granulocytes, and macrophages comprise myeloid-derived suppressor (MDSC) populations in many tumors; thus, tumor vaccines secreting GM-CSF may also drive production and accumulation of immunosuppressive MDSCs within tumors (Burga et al., 2015; Kohanbash et al., 2013). Strikingly, however, in an initial clinical trial, recombinant GM-CSF has shown potential as a combination therapy with anti-CTLA-4 immune checkpoint blockade in treatment of metastatic melanoma (Hodi et al., 2014).

Early immunotherapy studies also indicated the potential for Flt3L to promote anti-tumor responses (Lynch et al., 1997). Using a similar cancer vaccine approach, expression of Flt3L in melanoma cells increased tumor rejection as compared to a GM-CSF-expressing tumor vaccine. This effect was in part due to the ability of the Flt3L-expressing vaccine to increase tumor-associated cDC1s (inferred by CD11b−/lo staining) (Curran and Allison, 2009). Furthermore, the Flt3L-expressing vaccine synergized with anti-CTLA-4 checkpoint blockade therapy (Curran and Allison, 2009). More recently, systemic Flt3L treatment in combination with intratumoral injections of polyriboinosinic:polyribocytidylic acid (poly I:C), a TLR3 agonist, demonstrated a significant therapeutic effect in multiple mouse models of melanoma (Salmon et al., 2016). Flt3L stimulated the accumulation of cDC progenitors in the TME, the majority of which developed into CD103+ cDC1s, while poly I:C treatment induced their activation, promoting anti-tumor responses (Salmon et al., 2016). Taken together, DC growth factors play important roles in modulating tumor immunity and progression, and may serve as a basis for future cancer therapies. Since DCs are capable of inducing tolerance or immunity depending on microenvironmental context, roles for growth factors and effects on DC function may vary among tumor types.

4.2. IFN-I-STAT1, TLR, and STING signaling in DCs in the TME

IFN-I signaling in cDC1s is critical for the generation of cell-mediated immunity towards tumors (Diamond et al., 2011). IFN-I enhances the ability of cDC1s to cross-present antigen to naïve CD8+ T cells and stimulates anti-tumor immunity (Diamond et al., 2011). The ability of IFN-Is to promote immunity against murine melanoma was shown to require STAT1 signaling in response to type I IFN receptor- (IFNAR) stimulation (Fuertes et al., 2011). Accordingly, following tumor implantation, STAT1- or IFNAR-deficient mice show reduced intratumoral accumulation of cDC1s and decreased tumor-antigen specific T cell priming compared to wild type controls (Fuertes et al., 2011). Interestingly, in the absence of IFN-Is or STAT1, cDC1s were absent from the TME (Fuertes et al., 2011), suggesting IFN-I-STAT1 signals may also be required for the recruitment or local differentiation of cDC1s.

IFN-Is can be induced by the activation of a number of innate immune sensors, recognizing ligands naturally present in the TME. These sensors include certain TLR agonists such as tumor-derived DNA or RNA, which stimulate TLR3, TLR7 or TLR9 activation. Moreover, the STimulator of INterferon Genes (STING), which senses cytoplasmic DNA has been recognized as an important mediator of IFN-I production in the TME (Woo et al., 2014). By contrast, deficiency in MyD88, TRIF, TLR4, TLR9, P2X7R, or MAVS, which comprise important receptors or signaling proteins involved in innate recognition of pathogens and danger signals, did not impair spontaneous CD8+ T cell priming (Woo et al., 2014). Collectively, these data support the concept that STING is a crucial DNA sensor in the TME. This topic is covered in detail in the accompanying review by Vatner and Janssen in this issue, as well as an earlier review (Corrales et al., 2017).

Activation of other innate immune signaling pathways has been used in approaches such as tumor vaccine adjuvants to improve therapeutic responses in cancer. As mentioned earlier, intratumoral injection of poly I:C slowed tumor progression (Salmon et al., 2016), an effect that may be due to activation of TLR3-expressing CD103+ cDC1s in the TME. In addition, imiquimod, a TLR7 agonist, is an approved therapy for basal cell carcinoma, implicating pDC stimulation and production of IFN-Is as important in anti-tumor activity (Le Mercier et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2017). Others TLR agonists are in clinical trials or have been approved for use in cancer; this topic is covered in greater detail in an earlier review (Shi et al., 2016).

4.3. Immunosuppressive factors and STAT signaling in the TME

Although numerous potential stimulatory signals for DCs exist in the TME, many tumors also contain abundant amounts of immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10, which can be produced by TLR-stimulated DCs or macrophages. IL-10 suppresses DC-mediated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 upon TLR ligation, and consequently inhibits the ability of DCs to stimulate CD4+ Th1 polarization and CD8+ T cell activation (Ruffell et al., 2014; Yang and Lattime, 2003). Recently, we found that IL-10, as well as IL-6 and VEGF, were produced by murine melanoma cells and were expressed in melanoma tumors in vivo (Li et al., 2016b). Prior studies show IL-6 signaling in DCs inhibits the upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86, as well as CCR7, in response to TLR activation (Hegde et al., 2004; Park et al., 2004), while VEGF suppresses DC maturation from human hematopoietic progenitors in vitro (Gabrilovich et al., 1996; Oyama et al., 1998). In a study of human cancer patients, elevated circulating VEGF levels correlated with an increase in immature DCs, which lacked T cell stimulatory capacity, and a decrease in mature DCs (Almand et al., 2000). Consistently, administration of VEGF-neutralizing antibodies in tumor-bearing mice enhanced the abundance and function of DCs in lymphoid organs, and improved anti-tumor CD8+ T cell responses (Gabrilovich et al., 1999).

STAT3 is activated by IL-10, IL-6, and VEGF. Thus the aforementioned studies as well as original work using conditional STAT3 deletion mediated by the MX cre transgene implicated an immunosuppressive role for cytokine-responsive STAT3 signaling in DCs (Kortylewski et al., 2005). To formally test this concept, we used animals with DC-restricted STAT3 deletion (i.e., CD11c cre Stat3f/f mice) and the B16 melanoma tumor model. Our results revealed slower melanoma tumor growth in mice lacking STAT3 expression in DCs, compared to wild type controls. In addition, STAT3 deletion from DCs enhanced the ratio of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets versus Tregs in tumors, suggesting STAT3 signaling in DCs promotes an immunosuppressive tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) profile (Li et al., 2016b). The immunosuppressive activity of STAT3 was traced to inhibition of ID2, a transcriptional regulator required for cDC1 differentiation and function (Hacker et al., 2003; Li et al., 2016b). Significantly, overexpression of ID2 in GM-CSF-derived DCs, which were delivered intratumorally at an early stage of melanoma growth, slowed tumor progression when compared to the control DC vaccine. Furthermore, the ID2-expressing DCs suppressed Treg production in DC:naïve T cell co-cultures in vitro, and promoted an increase in IFN-γ-producing TILs versus Tregs upon vaccination in vivo (Li et al., 2016b). These data collectively implicate STAT3 and ID2 as negative and positive regulators of DC activity in melanoma, respectively. Future work is required to understand the transcriptional and molecular pathways that are controlled by these important regulators in DCs.

In addition to STAT3-activating cytokines, other factors in the TME inhibit DC function. For instance, PGE2 blocks DC differentiation in vitro, and is accompanied by low expression of MHC II, CD80, and CD40 (Yang et al., 2003). PGE2-mediated responses in DCs are dependent on expression of the EP2 receptor. Consistently, tumor growth studies in EP2-deficient mice demonstrated decreased tumor progression and prolonged survival, as well as increased DC and CD8+ T cells in TdLNs (Yang et al., 2003). Recent work showed that inhibition of IL-10-mediated signaling dramatically reduced the suppressive effect of PGE2 on DCs in vitro (Ahmadi et al., 2008), suggesting IL-10 contributes to the immunosuppressive activity of PGE2.

Signaling via the intracellular factor β-catenin also plays important roles in tumor-DC crosstalk in the TME. In murine melanoma, it was recently shown that a tumor-derived Wnt ligand (Wnt5a) promoted IDO production by DCs via β-catenin signaling, which led to increased DC-mediated Treg generation (Holtzhausen et al., 2015). In addition, deletion of the Wnt co-receptors LRP5 and LRP6 on DCs significantly delayed melanoma growth and correlated with increased DC abundance and proliferation of T effector cells in the TdLNs (Hong et al., 2016). Moreover, β-catenin signaling in melanoma cells was found to prevent CCL4-dependent recruitment of DCs and generation of anti-tumor immunity (Spranger et al., 2015).

TGF-β, an important signaling molecule involved in many aspects of tumor biology, was found in early studies to inhibit DC maturation in vitro (Yamaguchi et al., 1997). Interestingly, “immature” DCs, e.g., DCs expressing CD11c but low levels of MHC II and co-stimulatory molecules, have been implicated as an important source of TGF-β in the TdLNs, and thereby enhancing Treg expansion (Ghiringhelli et al., 2005). Overall, TGF-β is largely responsible for orchestrating an immunosuppressive environment through its interactions with many cell types in the TME. This topic has been reviewed in depth previously, and we refer readers to the following excellent resource (Flavell et al., 2010; Pickup et al., 2013).

5. Tumor-associated DCs and their roles in tumor immunity

5.1. Accurate DC identification in tumors

Early studies indicated that tumor-infiltrating DCs are defective in their ability to stimulate T cells and drive anti-tumor immune responses, thus enabling tumor growth. This was attributed to reduced expression of co-stimulatory molecules and subdued production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, along with elevated expression of inhibitory molecules such as PD-L1, by tumor associated DCs (Perrot et al., 2007; Stoitzner et al., 2008). These studies utilized CD11c and MHC II expression to identify DCs, which defines DCs broadly and includes MoDCs, a population that is significantly more abundant in most tumor types versus cDCs (Broz et al., 2014; Salmon et al., 2016). More recent work, analyzing many tumor types and stages of tumor development, has delineated cDC subsets with varying T cell stimulatory capacity and revealed that cDCs are a sparse population in most tumors (Broz et al., 2014; Edelson et al., 2010; Roberts et al., 2016; Salmon et al., 2016; Spranger et al., 2017). Thus, current methods for identifying DC subsets (Guilliams et al., 2016) (Table 1) allow for the specific characterization of DC phenotype and function within the TME.

The recognition of DCs as the principal intermediates between innate and adaptive immune responses, and the advent of immune checkpoint therapy for cancer, has spurred new investigation in DC function within the TME (Steinman, 2012; Topalian et al., 2015). Through careful profiling of distinct DC subsets in many tumor models and use of genetically modified mice with DC deficiencies, cDC1s (tissue resident CD103+ DCs) have emerged as the most potent activators of T cell mediated anti-tumor immunity. Nonetheless, pDCs and cDC2s also have appreciable but understudied roles in regulating immune responses to tumors. Here, we focus discussion on cDCs (versus MoDCs) in the TME, with particular attention to the roles and regulation of cDC1s.

5.2. cDC1s as principal inducers of T cell mediated tumor immunity

The superior ability of cDC1s to cross present exogenous antigens on MHC I and initiate CD8+ T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity was initially established in Batf3-deficient mice, which selectively lack cDC1s and demonstrate an inability to reject highly immunogenic fibrosarcoma tumors (Hildner et al., 2008). Since this seminal finding, Batf3-deficient mice have been used to test the necessity of cDC1s in other tumor types, and in response to immune checkpoint blockade and adoptive T cell therapy. Collectively, these studies demonstrated essential roles for cDC1s in initiating and sustaining CD8+ T cell responses toward melanoma, lymphoma, and colon tumors, as well as cancer immune therapy (Broz et al., 2014; Salmon et al., 2016; Sánchez-Paulete et al., 2016; Spranger et al., 2017). Furthermore, analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database revealed that the abundance of cDC1s in tumors correlates positively with patient survival across 12 different cancer types (Broz et al., 2014).

Although it is clear that cDC1s stimulate tumor-reactive CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (Hildner et al., 2008), the mechanisms that enable their selective ability to cross-present antigen are only now being uncovered. For example, early work showed splenic cDC1s and cDC2s have similar abilities to endocytose exogenous antigens (Schnorrer et al., 2006; Segura et al., 2009). Recent studies, however, revealed the endocytic compartment of tumor-infiltrating CD103+ cDC1s has a higher pH in comparison to other potential antigen-presenting cells in the TME (Broz et al., 2014). Elevated pH of the endocytic compartment is important for maintaining antigen cross-presentation function in DCs, and is mediated via a process involving NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) (Savina et al., 2006). Consistently, purification of antigen-presenting cells from the TME, followed by T cell priming and activation assays, demonstrated CD103+ cDC1s were the most efficient DC subset in activating naïve as well as previously primed CD8+ T cells (Broz et al., 2014). In addition, cDC1s effectively recognize and take up dead cell antigens via a process mediated by Clec9A, which contributes to their antigen cross-presentation function in cancer and viral infection (Sancho et al., 2008; Zelenay et al., 2012).

Importantly, recent studies have also shown that CD103+ cDC1s are the only DC population capable of transporting solid tumor antigens to tumor-draining lymph nodes (TdLNs), consistent with their tissue residence and ability to migrate upon activation (Roberts et al., 2016; Salmon et al., 2016). DCs migrate to LNs in response to the chemokine CCL21, which is secreted by lymphatic endothelial cells and signals via the CCR7 chemokine receptor expressed on the DC cell surface (Ohl et al., 2004) (Fig. 2). CCR7-deficient CD103+ cDC1s were impaired in LN migration and T cell priming towards B16 murine melanoma antigen, leading to enhanced melanoma progression (Roberts et al., 2016). Moreover, tumor antigen-containing CD103+ cDC1s were demonstrated to interact directly with CD8+ T cells in TdLNs (Roberts et al., 2016). By contrast, in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis, the induction of antigen-specific tolerance by cDC1s was also dependent on CCR7 expression (Idoyaga et al., 2013). Thus, future work to determine whether and how cDC1s and other DC populations actively promote antigen-specific tolerance versus immunity in LNs will aid in developing new therapies for cancer and immune disease.

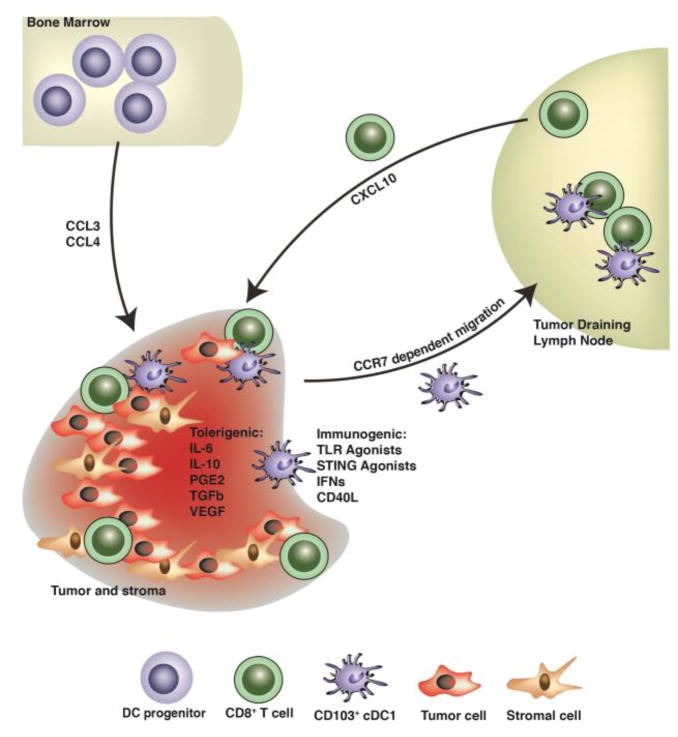

Fig. 2. Schematic illustration of trafficking and activation or tolerance signals regulating CD103+ cDC1s in the TME.

Pre-cDCs migrate to the TME, differentiate into CD103+ cDC1s, and integrate a variety of activating or tolerogenic signals, as shown. Tumor-associated CD103+ cDC1s subsequently migrate to the TdLNs to prime anti-tumor naïve CD8+ T cells. CD103+ cDC1s in the TME also secrete chemokines that recruit anti-tumor T cells, as indicated.

Recent studies using advanced imaging technology revealed that CD8+ T cells require interaction with antigen-bearing cDC1s for efficient activation (Hor et al., 2015; Kitano et al., 2016). An important factor contributing to cDC1:CD8+ T cell interaction is the selective expression of the chemokine receptor XCR1 by cDC1s. In LNs, cDC1s expressing XCR1+ serve as a central platform to engage CD4+ T cell help for optimized CD8+ T cell priming and CD8+ T cell memory responses (Eickhoff et al., 2015; Hor et al., 2015). In addition, activated CD8+ T cells in LNs upregulate the chemokine XCL1, which attracts XCR1+ cDC1 cells. These events orchestrate the formation of cDC1:T cell clusters that augment the priming and generation of the CD8+ cytotoxic T cell immune response (Brewitz et al., 2017; Hor et al., 2015; Kitano et al., 2016). Interestingly, clustering of XCR1+ cDC1s with CD8+ T cells has also been observed in the TdLNs of melanoma-bearing mice, but its relevance to mediating anti-tumor immunity needs to be further explored (Roberts et al., 2016). Taken together, studies suggest that the trafficking of tumor antigen to the TdLN by the CD103+ cDC1 population is critical for the generation of effective T cell-mediated immunity against solid tumors (Fig. 2). Of note, cDC1s can also transfer antigen to other DC populations residing in LN to activate CD8+ T cells (Allan et al., 2006).

5.3. Mechanisms regulating cDC1 accumulation in tumors

Pre-cDCs are recruited to tumors by the chemokine CCL3 (Fig. 2), which is produced primarily by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs); tumor-infiltrating pre-DCs subsequently undergo differentiation to cDCs (Iida et al., 2008). Moreover, the chemokine CCL4, secreted by Braf-mutant, PTEN-deficient (BrafV600E Pten−/−) murine melanoma cells, mediates recruitment of tissue-resident CD103+ cDC1s to melanoma tumors (Spranger et al., 2015). Consistently, the chemokine receptors CCR1 and CCR5, which are stimulated by CCL3 (CCR1) or CCL4 (CCR1 and CCR5), are necessary for accumulation of CD205+ cDCs (potentially cDC1s) as well as other CD11c+ cells in the TME (Iida et al., 2008). Strikingly, only mice with intact CCR1, CCR5, or CCL3 during primary tumor challenge could reject secondary tumors (Iida et al., 2008). Upon their recruitment, CD103+ cDC1s appear to be a primary source of the T cell chemoattractants CXCL10 (Spranger et al., 2017). These results are consistent with a positive correlation between tumor-associated CD103+ cDC1s and T cells, as exclusion of CD103+ cDC1s from melanoma tumors resulted in a profound lack of T cell infiltration (Spranger et al., 2015) (Fig. 2). Moreover, CCR5-dependent recruitment of CD103+ cDC1s was required for response of tumor-bearing animals to adoptive T cell transfer in conditions designed to mimic immunotherapy (Spranger et al., 2017). Taken together, these findings delineate the roles of CCL3, CCL4, CCR1, and CCR5, as well as CXCL10, in mediating the sequential recruitment of CD103+ cDC1s and effector T cells to the TME, respectively, to initiate and sustain anti-tumor immunity (Fig. 2).

5.4. Roles for cDC2s in solid tumors

As mentioned previously, early reports that focused on DC function in tumors typically used a broad definition of DCs, such as identification by the CD11c+ CD11b+ MHC II+ cell surface phenotype (or variations of these markers). Tissue-localized cDC2s and MoDCs share this expression profile (Broz et al., 2014; Guilliams et al., 2016), raising the possibility that early DC definitions and functional delineations may reflect a collection of subsets. In addition, a genetic model lacking cDC2s selectively, analogous to Batf3−/− mice deficient in cDC1, has not been developed or used extensively to study cDC2s in tumor immunity. Recent reports indicate cDC2s are capable of engulfing tumor antigen and inducing T cell proliferation in vitro, following their purification from the TME, suggesting cDC2s may contribute to stimulating anti-tumor T cell responses (Broz et al., 2014; Eickhoff et al., 2015; Hor et al., 2015) Nonetheless, cDC2s are not thought to be effective antigen cross-presenting cells, and significant gaps exist in our understanding of cDC2s in tumor immunity, particularly in light of the fact that cDC1s appear to play a dominant role (Broz et al., 2014; Hildner et al., 2008; Roberts et al., 2016; Salmon et al., 2016; Spranger et al., 2017). Moreover, whether cDC2s mediate tolerogenic responses or influence the migration or activity of other tumor-infiltrating immune subsets requires further investigation.

5.5. Roles for pDCs in solid tumors

Although pDCs do not typically reside in tissues in steady state, they are recruited to sites of inflammation as well as solid tumors, where they have shown conflicting roles. For example, the abundance of pDCs in human breast cancer and melanoma correlates with poor prognosis (Aspord et al., 2014; Sawant and Ponnazhagan, 2013), and depletion of pDCs (through use of anti-BST2 antibodies) in a murine orthotopic model of breast cancer significantly delayed tumor growth (Le Mercier et al., 2013). By contrast, imiquimod stimulates pDC production of IFN-Is and enhances anti-tumor cell-mediated immunity in humanized melanoma and orthotopic breast tumor models (Aspord et al., 2014; Le Mercier et al., 2013). Furthermore, CD40L- or TLR9-stimulated pDCs secrete IFN-Is in the TME, which helps promote NK- and CD8+ T cell-mediated responses against melanoma in tumor-bearing mice (Liu et al., 2008; Salio et al., 2003). Taken together, these findings suggest that the functional properties of pDCs in tumors are associated with their activation status, and stimulation of pDCs could be considered for targeted therapeutic approaches in human breast and melanoma tumors, and potentially other cancers.

In addition to secreting IFN-Is and other pro-inflammatory mediators in the TME, pDCs exhibit cytotoxic activity against human melanoma cells. For example, human pDCs activated by imiquimod or IFN-α, were able to lyse multiple human melanoma cell lines ex vivo (Kalb et al., 2012). Moreover, murine pDCs activated with either imiquimod or CpG (a TLR9 agonist) showed direct cytotoxic effects on mouse breast cancer cells in vitro, and suppressed tumor growth in vivo (Wu et al., 2017). Given the cytotoxic effects of IFN-Is, it is possible these responses result directly from pDC-mediated IFN-I production, although alternative mechanisms may also contribute. Interestingly, a recent study revealed that pDCs promoted XCL1-driven clustering of cDC1s and T cells in LNs in a model of vaccinia virus infection, a response that was mediated by pDC production of IFN-Is (Brewitz et al., 2017). Future studies are required to address the molecular basis of pDC-mediated toxicity toward tumor cells, as well as roles for pDCs in regulating other immune subsets and discrete cancer types.

5.6. DCs in hematological malignancies

Compared to solid tumors, fewer studies have probed the functions of DCs in hematological malignancies. Fully differentiated DC subsets are not found in abundance in the bone marrow or peripheral blood, major sites occupied by leukemic cells, which may reduce the ability of the immune system to detect leukemia versus tissue-localized (solid) tumors. Notably, however, defective DC production and function has been reported in patients with myeloproliferative disorders, myelodysplastic syndromes, acute/chronic myeloid leukemia (AML/CML), and T and B cell lymphoma (Galati et al., 2016). For example, both cDC1s and pDCs were reduced in the circulation of patients with CML and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, accompanied by impaired DC migration and antigen presentation activity (Dong et al., 2003; Fiore et al., 2006; Mohty et al., 2002; Mohty et al., 2004). Furthermore, the most commonly used therapeutic agent for CML, imatinib mesylate, was associated with enhanced pDC abundance and function (Mohty et al., 2004). While these data suggest impaired DC amounts or function may contribute to the progression of leukemia or lymphoma, a significant amount of work is required to understand roles for DCs in the progression of hematological malignancies.

6. DC-based therapies and tumor vaccines

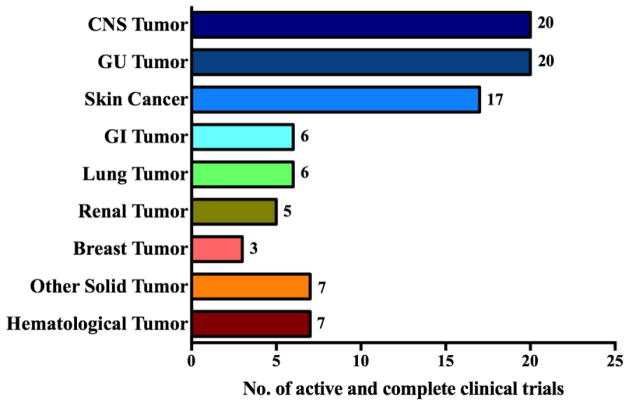

Various regimens, including those that mimic DC-expressed activating ligands for T cells (e.g., 4-1BB, OX40 agonist, CD40L), agents that stimulate DCs directly (e.g., CD40 agonists, TLR agonists), or mechanisms that block DC-mediated negative signals (e.g. anti-CTLA, anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1) have been studied extensively in experimental tumor models and, in many cases, tested in clinical trials for cancer (Eriksson et al., 2017; Freeman et al., 2000; Latchman et al., 2001; Leach et al., 1996; Melero et al., 2013; Richman and Vonderheide, 2014; Topalian et al., 2015; Vonderheide and Glennie, 2013). In addition, there has been much focus in the field directed toward expanding and activating DCs isolated from cancer patients for later therapeutic use. For example, DCs, monocytes, or progenitor cells have been isolated from peripheral blood samples, grown in conditions that promote DC proliferation and differentiation ex vivo, and used as an adoptive (autologous) cell therapy in cancer (Garg et al., 2017). Additionally, DCs that have been differentiated and activated using cocktails of growth factors, cytokines, and TLR or co-stimulatory agonists are also being investigated as cancer treatment options (Garg et al., 2017). Before DCs are administered back to the patient, they may be incubated with tumor cell lysates or specific tumor antigen-derived peptides. This is used to improve DC presentation of tumor antigens and resulting T cell responses toward the tumor. Currently, several clinical trials, using different variations of these approaches are in progress or recently completed; these are summarized herein (Fig. 3) and reviewed in depth elsewhere (Garg et al., 2017).

Fig. 3. DC vaccine-based clinical trials.

The graph shows the number of DC vaccine-based clinical trials in distinct cancers listed on clinicaltrial.gov from November 1999 to March 2017. Information for the following cancers is included: central nervous system (CNS) tumors (Medulloblastoma, Ependymoma, Gliobastoma Multiforme and Astrocytoma); genitourinary (GU) tumors (Prostate); skin tumors (Melanoma); gastrointestinal (GI) tumors (Colorectal, Pancreas, Esophagus); lung tumors (Mesothelioma, Adenocarcinoma, Non-Small Cell lung cancer, Small cell lung cancer); renal tumors (Renal cell carcinoma); breast tumors (Ductal carcinoma in situ); other solid tumors (Sarcomas, Neuroblastoma, Wilm’s Tumor, Ewing’s Sarcoma and Rhabdomyosarcoma); and hematological malignancies (Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Myeloma, Lymphoma).

Separately, strategies that target tumor antigens to DCs in vivo have been investigated for efficacy in treating cancer or viral infection. For example, antigens have been linked to antibodies against DC-specific endocytic receptors, such as DEC205, DC-SIGN, and Clec9A (Birkholz et al., 2010; Bonifaz et al., 2004; Tullett et al., 2016; Wakim et al., 2015; Wang, 2012) (Fehres et al., 2015; Macri et al., 2017). Importantly, when targeting peptides to receptors on DCs, the absence of adjuvant can lead to the induction of tolerogenic immunity to the antigen (Hawiger et al., 2001; Idoyaga et al., 2013), an undesirable response in tumor vaccination. Thus, further studies investigating the molecular mechanisms that regulate DC antigen presentation and immune activation is important for maximizing the clinical efficacy of DC-based therapies.

7. Concluding remarks

Studies over the last few decades have revealed important transcriptional and cytokine-driven pathways regulating DC differentiation. Moreover, DC function is dynamically modulated by microenvironmental factors including cytokines and chemokines present in the TME. In many cases, these elicit immunosuppressive activities and understanding mechanisms by which these inhibitory pathways can be circumvented is key to improving DC based immunotherapy. In exciting advances, several current studies have indicated the importance of the type 1 conventional DCs (cDC1s) in delivering tumor-associated antigens to prime cytotoxic T cells for anti-tumor immunity. This knowledge as well as improved methods to delineate DC subset identification, differentiation, migration, and activation triggers, may be incorporated to improve the efficacy of DC-based therapy in cancer.

Highlights.

Dendritic cells are the primary antigen presenting cells in the immune system, and comprise distinct subsets that are distinguished by morphology, immune function, and developmental regulation.

Dendritic cells are key mediators of immune tolerance and immune responses against tumors.

Cytokines, as well as their intracellular signaling proteins including STAT transcription factors have principal roles in regulating dendritic cell differentiation and function.

The type 1 conventional DCs (cDC1s) are specialized in delivering tumor-associated antigens to lymph nodes to activate cytotoxic T cells.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI109294 to S.S.W.), the MD Anderson Center for Inflammation and Cancer (to S.S.W. and H.S.L.)

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests. None of the authors affiliated with this manuscript have any commercial or associations that might pose a conflict interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmadi M, Emery DC, Morgan DJ. Prevention of both direct and cross-priming of antitumor CD8+ T-cell responses following overproduction of prostaglandin E2 by tumor cells in vivo. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7520–7529. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:675–680. doi: 10.1038/90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan RS, Waithman J, Bedoui S, Jones CM, Villadangos JA, Zhan Y, Lew AM, Shortman K, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Migratory dendritic cells transfer antigen to a lymph node-resident dendritic cell population for efficient CTL priming. Immunity. 2006;25:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almand B, Resser JR, Lindman B, Nadaf S, Clark JI, Kwon ED, Carbone DP, Gabrilovich DI. Clinical significance of defective dendritic cell differentiation in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1755–1766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KL, Perkin H, Surh CD, Venturini S, Maki RA, Torbett BE. Transcription factor PU. 1 is necessary for development of thymic and myeloid progenitor-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:1855–1861. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspord C, Leccia MT, Charles J, Plumas J. Melanoma hijacks plasmacytoid dendritic cells to promote its own progression. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e27402. doi: 10.4161/onci.27402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au-Yeung N, Mandhana R, Horvath CM. Transcriptional regulation by STAT1 and STAT2 in the interferon JAK-STAT pathway. JAKSTAT. 2013;2:e23931. doi: 10.4161/jkst.23931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Nakamoto Y, Mukaida N. Crucial contribution of thymic Sirp alpha+ conventional dendritic cells to central tolerance against blood-borne antigens in a CCR2-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2009;183:3053–3063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell BD, Kitajima M, Larson RP, Stoklasek TA, Dang K, Sakamoto K, Wagner KU, Kaplan DH, Reizis B, Hennighausen L, Ziegler SF. The transcription factor STAT5 is critical in dendritic cells for the development of TH2 but not TH1 responses. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:364–371. doi: 10.1038/ni.2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigley V, Barge D, Collin M. Dendritic cell analysis in primary immunodeficiency. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;16:530–540. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkholz K, Schwenkert M, Kellner C, Gross S, Fey G, Schuler-Thurner B, Schuler G, Schaft N, Dorrie J. Targeting of DEC-205 on human dendritic cells results in efficient MHC class II-restricted antigen presentation. Blood. 2010;116:2277–2285. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-268425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorck P. Isolation and characterization of plasmacytoid dendritic cells from Flt3 ligand and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-treated mice. Blood. 2001;98:3520–3526. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco P, Palucka AK, Pascual V, Banchereau J. Dendritic cells and cytokines in human inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008;19:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogunovic M, Ginhoux F, Helft J, Shang L, Hashimoto D, Greter M, Liu K, Jakubzick C, Ingersoll MA, Leboeuf M, Stanley ER, Nussenzweig M, Lira SA, Randolph GJ, Merad M. Origin of the lamina propria dendritic cell network. Immunity. 2009;31:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifaz LC, Bonnyay DP, Charalambous A, Darguste DI, Fujii S, Soares H, Brimnes MK, Moltedo B, Moran TM, Steinman RM. In vivo targeting of antigens to maturing dendritic cells via the DEC-205 receptor improves T cell vaccination. J Exp Med. 2004;199:815–824. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkowski TA, Letterio JJ, Farr AG, Udey MC. A role for endogenous transforming growth factor beta 1 in Langerhans cell biology: the skin of transforming growth factor beta 1 null mice is devoid of epidermal Langerhans cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2417–2422. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosschaerts T, Guilliams M, Stijlemans B, Morias Y, Engel D, Tacke F, Herin M, De Baetselier P, Beschin A. Tip-DC development during parasitic infection is regulated by IL-10 and requires CCL2/CCR2, IFN-gamma and MyD88 signaling. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001045. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewitz A, Eickhoff S, Dähling S, Quast T, Bedoui S, Kroczek RA, Kurts C, Garbi N, Barchet W, Iannacone M. CD8+ T cells orchestrate pDC-XCR1+ dendritic cell spatial and functional cooperativity to optimize priming. Immunity. 2017;46:205–219. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz ML, Binnewies M, Boldajipour B, Nelson AE, Pollack JL, Erle DJ, Barczak A, Rosenblum MD, Daud A, Barber DL. Dissecting the tumor myeloid compartment reveals rare activating antigen-presenting cells critical for T cell immunity. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:638–652. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burga RA, Thorn M, Point GR, Guha P, Nguyen CT, Licata LA, DeMatteo RP, Ayala A, Espat NJ, Junghans RP. Liver myeloid-derived suppressor cells expand in response to liver metastases in mice and inhibit the anti-tumor efficacy of anti-CEA CAR-T. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64:817–829. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1692-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess AW, Camakaris J, Metcalf D. Purification and properties of colony-stimulating factor from mouse lung-conditioned medium. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:1998–2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess AW, Metcalf D. The nature and action of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factors. Blood. 1980;56:947–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butte MJ, Keir ME, Phamduy TB, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. Programmed death-1 ligand 1 interacts specifically with the B7-1 costimulatory molecule to inhibit T cell responses. Immunity. 2007;27:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell IK, van Nieuwenhuijze A, Segura E, O’Donnell K, Coghill E, Hommel M, Gerondakis S, Villadangos JA, Wicks IP. Differentiation of inflammatory dendritic cells is mediated by NF-kappaB1-dependent GM-CSF production in CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:5468–5477. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitini CM, Nasholm NM, Chien CD, Larabee SM, Qin H, Song YK, Klover PJ, Hennighausen L, Khan J, Fry TJ. Absence of STAT1 in donor-derived plasmacytoid dendritic cells results in increased STAT3 and attenuates murine GVHD. Blood. 2014;124:1976–1986. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-500876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carotta S, Dakic A, D’Amico A, Pang SH, Greig KT, Nutt SL, Wu L. The transcription factor PU. 1 controls dendritic cell development and Flt3 cytokine receptor expression in a dose-dependent manner. Immunity. 2010;32:628–641. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caton ML, Smith-Raska MR, Reizis B. Notch-RBP-J signaling controls the homeostasis of CD8- dendritic cells in the spleen. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1653–1664. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caux C, Vanbervliet B, Massacrier C, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, de Saint-Vis B, Jacquet C, Yoneda K, Imamura S, Schmitt D, Banchereau J. CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors from human cord blood differentiate along two independent dendritic cell pathways in response to GM-CSF+TNF alpha. J Exp Med. 1996;184:695–706. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Flies DB. Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:227–242. doi: 10.1038/nri3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LS, Wei PC, Liu T, Kao CH, Pai LM, Lee CK. STAT2 hypomorphic mutant mice display impaired dendritic cell development and antiviral response. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:22. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YL, Chen TT, Pai LM, Wesoly J, Bluyssen HA, Lee CK. A type I IFN-Flt3 ligand axis augments plasmacytoid dendritic cell development from common lymphoid progenitors. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2515–2522. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chicha L, Jarrossay D, Manz MG. Clonal type I interferon–producing and dendritic cell precursors are contained in both human lymphoid and myeloid progenitor populations. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1519–1524. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisse B, Caton ML, Lehner M, Maeda T, Scheu S, Locksley R, Holmberg D, Zweier C, den Hollander NS, Kant SG, Holter W, Rauch A, Zhuang Y, Reizis B. Transcription factor E2-2 is an essential and specific regulator of plasmacytoid dendritic cell development. Cell. 2008;135:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook AD, Braine EL, Hamilton JA. Stimulus-dependent requirement for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in inflammation. J Immunol. 2004;173:4643–4651. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coquet JM, Ribot JC, Babala N, Middendorp S, van der Horst G, Xiao Y, Neves JF, Fonseca-Pereira D, Jacobs H, Pennington DJ, Silva-Santos B, Borst J. Epithelial and dendritic cells in the thymic medulla promote CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell development via the CD27-CD70 pathway. J Exp Med. 2013;210:715–728. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrales L, Matson V, Flood B, Spranger S, Gajewski TF. Innate immune signaling and regulation in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res. 2017;27:96–108. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran MA, Allison JP. Tumor vaccines expressing flt3 ligand synergize with ctla-4 blockade to reject preimplanted tumors. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7747–7755. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico A, Wu L. The early progenitors of mouse dendritic cells and plasmacytoid predendritic cells are within the bone marrow hemopoietic precursors expressing Flt3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:293–303. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daro E, Pulendran B, Brasel K, Teepe M, Pettit D, Lynch DH, Vremec D, Robb L, Shortman K, McKenna HJ, Maliszewski CR, Maraskovsky E. Polyethylene glycol-modified GM-CSF expands CD11b(high)CD11c(high) but notCD11b(low)CD11c(high) murine dendritic cells in vivo: a comparative analysis with Flt3 ligand. J Immunol. 2000;165:49–58. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darrasse-Jèze G, Deroubaix S, Mouquet H, Victora GD, Eisenreich T, Yao K-h, Masilamani RF, Dustin ML, Rudensky A, Liu K, Nussenzweig MC. Feedback control of regulatory T cell homeostasis by dendritic cells in vivo. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2009;206:1853–1862. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond MS, Kinder M, Matsushita H, Mashayekhi M, Dunn GP, Archambault JM, Lee H, Arthur CD, White JM, Kalinke U. Type I interferon is selectively required by dendritic cells for immune rejection of tumors. J Exp Med, jem. 2011:20101158. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao J, Zhao J, Winter E, Cattral MS. Recruitment and differentiation of conventional dendritic cell precursors in tumors. The journal of immunology. 2010;184:1261–1267. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson RE, Griffin H, Bigley V, Reynard LN, Hussain R, Haniffa M, Lakey JH, Rahman T, Wang XN, McGovern N, Pagan S, Cookson S, McDonald D, Chua I, Wallis J, Cant A, Wright M, Keavney B, Chinnery PF, Loughlin J, Hambleton S, Santibanez-Koref M, Collin M. Exome sequencing identifies GATA-2 mutation as the cause of dendritic cell, monocyte, B and NK lymphoid deficiency. Blood. 2011;118:2656–2658. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-360313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez PM, Ardavin C. Differentiation and function of mouse monocyte-derived dendritic cells in steady state and inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2010;234:90–104. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong R, Cwynarski K, Entwistle A, Marelli-Berg F, Dazzi F, Simpson E, Goldman JM, Melo JV, Lechler RI, Bellantuono I, Ridley A, Lombardi G. Dendritic cells from CML patients have altered actin organization, reduced antigen processing, and impaired migration. Blood. 2003;101:3560–3567. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dranoff G, Jaffee E, Lazenby A, Golumbek P, Levitsky H, Brose K, Jackson V, Hamada H, Pardoll D, Mulligan RC. Vaccination with irradiated tumor cells engineered to secrete murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates potent, specific, and long-lasting anti-tumor immunity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1993;90:3539–3543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durai V, Murphy KM. Functions of Murine Dendritic Cells. Immunity. 2016;45:719–736. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dursun E, Endele M, Musumeci A, Failmezger H, Wang SH, Tresch A, Schroeder T, Krug AB. Continuous single cell imaging reveals sequential steps of plasmacytoid dendritic cell development from common dendritic cell progenitors. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37462. doi: 10.1038/srep37462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzionek A, Fuchs A, Schmidt P, Cremer S, Zysk M, Miltenyi S, Buck DW, Schmitz J. BDCA-2, BDCA-3, and BDCA-4: three markers for distinct subsets of dendritic cells in human peripheral blood. J Immunol. 2000;165:6037–6046. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelson BT, Kc W, Juang R, Kohyama M, Benoit LA, Klekotka PA, Moon C, Albring JC, Ise W, Michael DG, Bhattacharya D, Stappenbeck TS, Holtzman MJ, Sung SS, Murphy TL, Hildner K, Murphy KM. Peripheral CD103+ dendritic cells form a unified subset developmentally related to CD8alpha+ conventional dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:823–836. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AD, Chaussabel D, Tomlinson S, Schulz O, Sher A, Reis e Sousa C. Relationships among murine CD11c(high) dendritic cell subsets as revealed by baseline gene expression patterns. J Immunol. 2003;171:47–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff S, Brewitz A, Gerner MY, Klauschen F, Komander K, Hemmi H, Garbi N, Kaisho T, Germain RN, Kastenmüller W. Robust anti-viral immunity requires multiple distinct T cell-dendritic cell interactions. Cell. 2015;162:1322–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson E, Moreno R, Milenova I, Liljenfeldt L, Dieterich LC, Christiansson L, Karlsson H, Ullenhag G, Mangsbo SM, Dimberg A, Alemany R, Loskog A. Activation of myeloid and endothelial cells by CD40L gene therapy supports T-cell expansion and migration into the tumor microenvironment. Gene Ther. 2017;24:92–103. doi: 10.1038/gt.2016.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esashi E, Wang YH, Perng O, Qin XF, Liu YJ, Watowich SS. The signal transducer STAT5 inhibits plasmacytoid dendritic cell development by suppressing transcription factor IRF8. Immunity. 2008;28:509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esterhazy D, Loschko J, London M, Jove V, Oliveira TY, Mucida D. Classical dendritic cells are required for dietary antigen-mediated induction of peripheral Treg cells and tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:545–555. doi: 10.1038/ni.3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts B, Amiel E, Huang SC, Smith AM, Chang CH, Lam WY, Redmann V, Freitas TC, Blagih J, van der Windt GJ, Artyomov MN, Jones RG, Pearce EL, Pearce EJ. TLR-driven early glycolytic reprogramming via the kinases TBK1-IKKvarepsilon supports the anabolic demands of dendritic cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:323–332. doi: 10.1038/ni.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fainaru O, Shseyov D, Hantisteanu S, Groner Y. Accelerated chemokine receptor 7-mediated dendritic cell migration in Runx3 knockout mice and the spontaneous development of asthma-like disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10598–10603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504787102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancke B, Suter M, Hochrein H, O’Keeffe M. M-CSF: a novel plasmacytoid and conventional dendritic cell poietin. Blood. 2008;111:150–159. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehres CM, van Beelen AJ, Bruijns SC, Ambrosini M, Kalay H, van Bloois L, Unger WW, Garcia-Vallejo JJ, Storm G, de Gruijl TD, van Kooyk Y. In situ Delivery of Antigen to DC-SIGN(+)CD14(+) Dermal Dendritic Cells Results in Enhanced CD8(+) T-Cell Responses. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2228–2236. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore F, Von Bergwelt-Baildon MS, Drebber U, Beyer M, Popov A, Manzke O, Wickenhauser C, Baldus SE, Schultze JL. Dendritic cells are significantly reduced in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and express less CCR7 and CD62L. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:613–622. doi: 10.1080/10428190500360971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]