Abstract

Although sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) is associated with poorer peer functioning, no study has examined SCT in relation to student-teacher relationship quality. The current study examined whether SCT, as rated by both teachers and children, was uniquely associated with poorer student-teacher relationship quality above and beyond child demographics and other mental health symptoms (i.e., attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder [ODD/CD], anxiety/depression). Sex was examined as a possible moderator of the association between SCT and student-teacher relationship quality. Participants were 176 children in 1st–6th grades and their teachers. Teachers rated children’s SCT and other mental health symptoms in the fall semester (T1) and the student-teacher relationship (conflict and closeness) six months later (T2). Children provided self-ratings of SCT at T2. Above and beyond age, sex, and other mental health symptoms, teacher-rated SCT at T1 was associated with greater student-teacher conflict at T2. This association was qualified by a SCT×Sex interaction, with SCT associated with greater conflict for girls but not boys. Further, child-rated SCT was also associated with greater teacher-rated conflict, above and beyond covariates. In addition, teacher-rated SCT at T1 was the only mental health dimension to be significantly associated with less student-teacher closeness at T2. Findings extend the social difficulties associated with SCT to the student-teacher relationship, an important relationship associated with children’s academic and socio-emotional outcomes.

Keywords: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders, sex differences, sluggish cognitive tempo, teacher-student relationship

A growing body of research indicates that sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) symptoms are common in youth and uniquely associated with academic and social difficulties (Barkley, 2013; Becker et al., 2016). SCT is most commonly characterized by excessive daydreaming, sluggishness, appearing tired/lethargic, slowed thinking, and mental confusion or fogginess (Becker et al., 2016). Factor analytic work indicates SCT is distinct from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) inattentive symptoms (Becker et al., 2016), as well as depression and anxiety (Becker, Luebbe, Fite, Stoppelbein, & Greening, 2014; Willcutt et al., 2014). Although SCT is currently not assessed in the school setting, accumulating findings indicate SCT is relevant to students’ educational functioning and to the work of school psychologists and other school personnel. For instance, SCT symptoms are associated with more organizational and homework problems (Langberg, Becker & Dvorsky, 2014) and academic impairment over time (Bernad, Servera, Grases, Collado & Burns, 2014), as well as lower grade point average (Langberg et al., 2014; Willcutt et al., 2014). However, the impact of SCT in the school environment remains largely unknown and critically important for understanding how best to aid students displaying SCT symptomatology.

SCT and Children’s Social Functioning

A consistent finding in SCT research is an association between SCT and social impairment, with a recent meta-analysis finding SCT to be moderately correlated with social impairment in children and adolescents (r = 0.38; Becker et al., 2016). It is estimated that 75% of students with high levels of SCT are perceived by their teachers as impaired in the peer domain (Becker, 2014). There is not yet consensus as to whether SCT is best defined as a unidimensional or multidimensional construct (Becker, Burns, Schmitt, Epstein, & Tamm, 2017; Becker, Luebbe, & Joyce, 2015; Fenollar Cortés, Servera, Becker, & Burns, 2017; Smith & Langberg, 2017). However, studies using either unidimensional or multidimensional measures of SCT have demonstrated relations with social difficulties. Examined unidimensionally, SCT has been found to be associated with greater social withdrawal, peer ignoring, lower rates of social participation and leadership, and a higher likelihood to miss subtle social cues (Becker et al., 2017; Marshall et al., 2014; Mikami et al., 2007). There is also preliminary evidence that teachers may be concerned with SCT behaviors, as Meisinger and Lefler (2016) found that pre-service teachers rated similar levels of concern for students described as having SCT, ADHD, or social anxiety, and also rated SCT behaviors as worthy of a referral for services. As a multidimensional construct, Fenollar Cortés and colleagues (2017) reported a two-factor structure of SCT in a sample of children and adolescents with a diagnosis of ADHD that included an inconsistent alertness factor (e.g., daydreams, absentminded) and a slowness factor (e.g., seems drowsy, slow moving). The inconsistent alertness dimension of SCT was associated with peer problems above and beyond other mental health symptoms, whereas the slowness dimension was not associated with social impairment among peers after controlling for covariates. However, it is unknown whether SCT, measured as either a unidimensional or multidimensional construct, is associated with student-teacher relationship quality, a critical predictor of children’s educational success in the school setting.

Importance and Correlates of the Student-Teacher Relationship

The student-teacher relationship is a critical developmental context associated with students’ social functioning (Ladd, Birch, & Buhs, 1999), behavior problems (Graziano, Reavis, Keane, & Calkins, 2007), and academic achievement and engagement (see Roorda, Koomen, Spilt & Oort, 2011 for a review). Closeness in the student-teacher relationship is positively associated with student engagement and achievement, and conflict is negatively associated with these domains in the elementary classroom (Roorda et al., 2011). Longitudinally, high conflict is associated with increased problem behavior, decreased prosocial behavior, lower student grades, lower standardized test scores, and poorer work habits (Birch & Ladd, 1998; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Pianta, Nimetz, & Bennett, 1997). Studies that help identify those students who may be most likely to have student-teacher relationship problems may allow school-based mental health providers to more readily identify those students early and consider appropriate supports that reduce the need for costly future intervention (Hamre & Pianta, 2001).

Student mental health symptoms are associated with student-teacher relationship quality, with both externalizing and internalizing symptoms associated with higher levels of student-teacher conflict (Henricsson & Rydell, 2004; Murray & Murray, 2004) and, to a less clear degree, lower levels of student-teacher closeness (Arbeau, Coplan, & Weeks, 2010; Skinner & Belmont, 1993). Specifically, previous research has found externalizing symptoms of ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and conduct disorder (CD) to be most strongly associated with student-teacher conflict, whereas internalizing symptoms of anxiety and depression are less strongly associated with student-teacher conflict (Henricsson & Rydell, 2004; Murray & Murray, 2004). In contrast, internalizing symptoms are more strongly associated than externalizing symptoms with lower student-teacher closeness (Henricsson & Rydell, 2004; Murray & Murray, 2004). It is clear that students with mental health symptoms are at increased risk for disrupted student-teacher relationships, though no study has examined SCT in relation to the student-teacher relationship, which is an important gap in the literature.

Student sex also appears to be related to student-teacher relationship quality. Research has found that girls are more socially competent, have fewer behavior problems, and exhibit higher levels of closeness and lower levels of conflict, as compared to boys (Justice et al., 2008; Wanless et al., 2013). Although these differences likely emerge from a confluence of factors (Leaper & Friedman, 2007), socialization and the ways in which adults and peers reinforce differential expectations for boys and girls has been one common area of inquiry (Carpenter, Huston, & Holt, 1986; Serbin, O’Leary, Kent & Tonick, 1973). For teachers, this is manifested as stereotyped beliefs regarding students’ appropriate behavior in the classroom that result in differential noticing, reinforcement, and discipline based on student sex. In considering SCT specifically, it is possible that teachers view these behaviors (e.g., excessive daydreaming, mental confusion, slowed behavior/thinking) and their correlates (e.g., social withdrawal, reticence, isolation) as more challenging when displayed by girls compared to boys since they are in contrast to expectations that girls are compliant, ready and eager to learn, and socially competent (Jones & Myhill, 2004). In support of this theory, a study of teacher appraisals of student problematic behaviors by Kokkinos, Panayiotou, and Davazoglou (2005) provided teachers with lists of problematic behaviors and asked teachers to rate how problematic they viewed each behavior to be. Surveys were randomized to describe the behaviors as exhibited by boys or girls. Experienced teachers rated externalizing difficulties as being more problematic when exhibited by boys, while internalizing and inattentive problems were appraised as being more problematic when exhibited by girls. Since SCT is considered an attentional problem that may fall under the internalizing umbrella of psychopathology (Becker et al., 2013), SCT behaviors may also be viewed as more problematic when exhibited by girls as compared to boys. In sum, it is not only important to evaluate whether SCT is associated with student-teacher relationship quality, but also explore whether this association differs for boy and girl students.

The Present Study

Although significant evidence demonstrates that SCT is negatively associated with social impairment (Becker et al., 2016), no studies have examined SCT and the student-teacher relationship. The purpose of the present study was to test the hypothesis that SCT would be associated with poorer student-teacher relationship quality. We evaluated this hypothesis in a school-based study using a multi-informant design. Specifically, using a short-term longitudinal design we examined whether teacher-rated SCT (and other mental health dimensions) in the fall semester predicted student-teacher relationship quality in the spring semester (6 months later). Students also completed self-ratings of SCT in the spring semester, and so we were also able to examine whether child-rated SCT was concurrently associated with student-teacher relationship quality. As SCT commonly co-occurs with other mental health symptoms that are likely to impact the student-teacher relationship (Becker et al., 2016), the current study examines whether SCT predicts poorer student-teacher relationship quality above and beyond other common mental health symptoms. Specifically, because previous studies have found that externalizing and internalizing behaviors congruent with symptoms of ADHD (e.g., impulsivity, inattention), ODD/CD (e.g., oppositionality, aggression), and depression/anxiety (e.g., sadness, worry) are associated with the student-teacher relationship, measures of these constructs were included as covariates (Baker, Grant, & Morlock, 2008; Murray & Murray, 2004). Further, because there is not consensus in the field whether SCT is best conceptualized as unidimensional or multidimensional (Becker et al., 2016), the current study examined the factor structure of SCT as rated by teachers and students prior to analyzing relations with student-teacher closeness and conflict. Finally, we explored whether the association between SCT and student-teacher relationship quality was moderated by sex. Based on previous research (Kokkinos et al., 2005) we expected that the relations between SCT and the student-teacher relationship would be stronger for girls as compared to boys.

Methods

Participants

The current study included teacher ratings of 176 students attending an elementary school in the Midwestern United States. Students included in this study were in first through sixth grades (ages 6–13 at the fall time point, M = 9.17, SD = 1.82). The sample was approximately equally split between boys (n = 82; 47%) and girls (n = 94; 53%). Most participants in this study were White (n = 164; 93%) with remaining participants African American (n = 9; 5%) or Asian (n = 3; 2%). Fifty-two percent (n = 92) of the students received free/reduced lunch, which was used in the present study as a marker of socioeconomic status. Demographics and socioeconomic status of students in the school were consistent with the surrounding community. According to the 2010 Census, 28.4% of the city population was below the federal poverty level (median household income = $30,299). To further describe the sample, the county in which the school resides is classified by the 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes as nonmetropolitan (specifically, Code 6: Urban population of 2,500 to 19,999, adjacent to a metro area).

Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the university Institutional Review Board and are described in more detail elsewhere (Becker, 2014). One month into the school year, the principal investigator described the study to teachers of 1st–6th grades. All 12 eligible teachers (i.e., mainstream classroom teachers; 100% female) provided signed informed consent to participate. After teachers provided consent, the study was described by research staff to the students in each teacher’s classroom. After answering any questions, students were given informed consent forms for them to take home to their parents. Of the 280 total students in 1st–6th grades in October (T1), 218 returned their consent forms, 189 had parents who provided consent for participation, and 176 were still attending the school in April (T2) and were included in the current study analyses. Teachers completed measures for each participating student in T1 and T2. Participating students from each grade completed the surveys in a group setting. See Becker (2014) for additional details.

Measures

Child demographic variables

School records were used to gather demographic information (i.e., age, sex, race, free/reduced lunch status) for each participating student.

Teacher-rated SCT

The Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Scale (SCTS) (Penny, Waschbusch, Klein, Corkum, & Eskes, 2009) was completed by teachers to assess children’s SCT symptoms. Teachers completed the SCT measure at both T1 and T2; in the present study, we prioritize using the T1 SCT data since this allows for a longitudinal analysis in predicting T2 student-teacher relationship quality. However, analyses using the T2 SCT data were also conducted to replicate and bolster confidence in the longitudinal findings. The SCTS consists of 14 items rated on a four-point scale (0 = not at all, 3 = very much). As in previous research (Becker, Garner et al., 2017), 10 items from the SCTS were used as a measure of SCT in the present study. These 10 items were selected based on findings from a recent meta-analysis of SCT items (Becker et al., 2016). Using items identified in the meta-analysis ensures that the items used for measuring SCT are not sample-specific but are instead considered optimal for assessing SCT across a range of sample types (e.g., community, school, clinical) and raters (e.g., teachers, child self-report). In addition, and perhaps most importantly, these 10 items were identified in the meta-analysis as consistently loading on a SCT factor and not cross-loading with ADHD inattention. The 10 items used to measure SCT in the present study are: (1) is apathetic; shows little interest in things or activities, (2) is unmotivated, (3) appears to be sluggish, (4) seems drowsy, (5) daydreams, (6), appears tired; lethargic, (7) gets lost in his or her own thoughts, (8) seems to be in a world of his or her own, (9) has a yawning, stretching, sleepy-eyed appearance, and (10) is underactive, slow moving, or lacks energy. The four excluded items (is slow or delayed in completing tasks, lacks initiative to complete work, effort on tasks fades quickly, needs extra time for assignments) did not demonstrate discriminant validity from ADHD inattention in initial validation studies of the SCTS (Penny et al., 2009) or in the subsequent meta-analysis (Becker et al., 2016). In the present study, the internal consistency for the 10-item SCT scale was acceptable (T1 α = 0.92, T2 α = 0.95).

Child-rated SCT

The Child Concentration Inventory (CCI; Becker, et al., 2015) was used to assess children’s self-reported SCT symptoms. The CCI is a child self-report version of the teacher-rated SCTS described above. Each of the 14 CCI items (e.g., “I get lost in my own thoughts”) is rated on a four-point scale (0 = not at all to 3 = very much). For the present study 10 items from the CCI were used that parallel the 10 teacher-rated SCT items. It is important to note that children only completed the CCI at T2 (no longitudinal data were available for the CCI), when they were further along in their reading and comprehension skills (α = 0.76 among first-grade students; α = 0.77 in the full sample).

ADHD, ODD/CD, and internalizing behaviors

At T1 and T2, teachers completed the 35-item Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Teacher Rating Scale (VADTRS; Wolraich et al., 2013), a well-validated teacher-report measure of child mental health symptoms. The VADTRS includes 18 items that correspond to the DSM-IV symptoms of ADHD in addition to 10 items assessing ODD/CD problems and 7 items assessing internalizing (anxiety/depression) problems. Each item is rated on a four-point scale (0 = never, 1 = occasionally, 2 = often, 3 = very often). In the present study, internal consistencies of the mean scale scores were acceptable at T1 (and T2): ADHD α = 0.94 (0.96), ODD/CD α = 0.89 (0.89), internalizing α = 0.87 (0.83).

Student-teacher relationship quality

Teachers completed the Student-Teacher Relationship Scale: Short Form (STRS; Pianta, 2001) at T2. Comprised of 15 items, the STRS assesses both relationship closeness (7 items; e.g., “I share a warm, affectionate relationship with this child”) and conflict (8 items; e.g., “Dealing with this child drains my energy”) rated on a five-point scale (1 = definitely does not apply to 5 = definitely applies). In the present study, αs = 0.87 and 0.89 for closeness and conflict, respectively.

Statistical analyses

First, exploratory factor analyses (EFAs) in Mplus Version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017) were conducted to determine if the 10 SCT items were best represented as one or multiple SCT dimensions. A separate EFA was conducted for teacher- and child-rated SCT (for both EFAs, up to three factors were considered; Penny et al., 2009). The robust weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV) with oblique geomin rotation was used. We examined eigenvalues (i.e., >1) as well as previous SCT factor analytic research (Becker, Burns, et al., 2017; Fenollar Cortés et al., 2017; Penny et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2016) to determine the optimal factor structure of the SCT items for teacher- and child-report.

Second, zero-order correlations were examined to test the hypothesis that teacher and child ratings of SCT would be associated with poorer student-teacher relationship quality. A correlation of .10 is considered a small effect, .30 is considered a medium effect, and .50 is considered a large effect (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). Associations of age, sex, free/reduced lunch status, and internalizing/externalizing problems with student-teacher closeness and conflict were also evaluated. Any variable that was significantly (p < .05) correlated with either closeness or conflict was included as a covariate in all regression analyses.

Third, hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine whether SCT remained associated with student-teacher relationship quality above and beyond covariates. Separate regression models were conducted for teacher-rated SCT (longitudinal models) and child-rated SCT (cross-sectional models) in relation to student-teacher relationship quality. The regression analyses were also used to explore whether the association between SCT and student-teacher relationship quality was moderated by sex. Specifically, covariates were entered at Step 1, SCT was entered at Step 2, and the Sex × SCT interaction was entered at Step 3. The primary models included the teacher- and child-rated SCT total score. For child self-reported SCT (see EFA Results below), models were re-run with the SCT dimensions as well as the interactions of sex with each of the SCT dimensions as exploratory analyses. Significant interactions were plotted using procedures outlined by Holmbeck (2002). Specifically, regression equations were calculated separately for boys and girls, and substituted values of one standard deviation below and above the mean (±1 SD) for SCT were used in each equation in order to produce graphs of the moderated effect (note, however, that continuous SCT variables were used in all regression analyses). Although students were nested within teachers’ classrooms, the small number of teachers/classrooms (N = 12) precluded using multilevel modeling or the Type = Complex option in Mplus. Therefore, to account for the non-independent nature of the data due to nesting within classrooms, we followed recommendations to create eleven dummy variables that were entered as covariates in all regression analyses (Muthén, 2013). For all analyses, statistical significance was set at p < .05.

Results

Factor Structure of SCT Items

The EFA for the teacher-rated T1 SCT items yielded only one eigenvalue >1 (eigenvalue = 7.39), indicating that the 10 SCT items are best represented as a single dimension. All 10 items significantly loaded on the SCT factor, with all factor loadings >0.60 (range: 0.65 to 0.96).1

The EFA for the child-rated SCT items yielded three eigenvalues >1 (eigenvalues = 4.16, 1.48, 1.02). These three factors were Drowsy (items 1, 4, 6, 9 in Measures description above; factor loadings: 0.45 to 1.06), Underactive (items 3, 10; factor loadings: 0.80 and 0.95), and Daydreaming (items 5, 7, 8; factor loadings: 0.51 to 0.82). Item 2 (“unmotivated”) cross-loaded on both the Drowsy and Underactive factors and was not included on either dimension in subsequent analyses. All other items had a primary factor loading ≥.45 on its respective factor, absolute factor loadings <.35 on the alternative factors, and a factor loading difference of >.20 on the primary factor compared to the alternative factors. The Drowsy and Underactive dimensions were significantly correlated (0.61, p < .05), whereas the Daydreaming factor was not significantly correlated with either the Drowsy or Underactive dimension (0.25 and 0.22, respectively; ps > .05). Internal consistency for the three dimensions was: Drowsy α = 0.69, Underactive α = 0.76, Daydreaming α = 0.79. Given these findings, primary analyses were conducted with the total SCT score, with supplementary analyses conducted using the three child-report SCT dimensions.

Correlation Analyses

Correlations among study variables are summarized in Table 1. Male sex was associated with both less closeness (r = −.16, p = .04) and more conflict (r = .23, p = .002). All mental health symptom dimensions were significantly correlated with increased student-teacher conflict, with effects generally in the medium-to-large range. Both T1 teacher-rated SCT and T2 child-rated SCT were significantly positively correlated with student-teacher conflict (rs = .50 and .38, respectively, both ps < .001). In addition, among the mental health variables, only SCT was significantly correlated with less student-teacher closeness, with correlations in the small-to-medium range and consistently significant across T1 teacher-rated SCT (r = −.16, p = .03) as well as T2 child-rated SCT (r = −.18, p = .02).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations of Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | – | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Lunch Status | −.13 | – | |||||||||||||||

| 3. T1 Age | −.03 | .03 | – | ||||||||||||||

| 4. T1 ADHD | .23** | .14 | .12 | – | |||||||||||||

| 5. T1 ODD/CD | .17* | .02 | .21** | .50*** | – | ||||||||||||

| 6. T1 Anx/Dep (TR) | .09 | .05 | .18* | .56*** | .59*** – | ||||||||||||

| 7. T1 SCT (TR) | .25** | .18* | .16* | .69*** | .33*** | .46*** | – | ||||||||||

| 8. T2 ADHD | .25** | .17* | .15 | .83*** | .42*** | .42*** | .57*** | – | |||||||||

| 9. T2 ODD/CD | .17* | .13 | .20** | .53*** | .71*** | .39*** | .37*** | .55*** | – | ||||||||

| 10. T2 Anx/Dep (TR) | .08 | .12 | .28*** | .53*** | .37*** | .56*** | .48*** | .56*** | .41*** | – | |||||||

| 11. T2 SCT (TR) | .18* | .20** | .19* | .50*** | .18* | .35*** | .76*** | .60*** | .28*** | .53*** | – | ||||||

| 12. T2 SCT (SR) | .22** | .03 | −.01 | .39*** | .31*** | .34*** | .38*** | .48*** | .27*** | .36*** | .43*** | – | |||||

| 13. T2 SCT Drowsy (SR) | .21** | −.09 | −.05 | .22** | .21** | .19* | .24** | .27*** | .16* | .27*** | .27*** | .80*** | – | ||||

| 14. T2 SCT Underactive (SR) | .23** | .04 | −,01 | .37*** | .30*** | .27*** | .29*** | .40*** | .27*** | .24** | .28*** | .68*** | .42*** | – | |||

| 15. T2 SCT Daydreaming (SR) | .04 | .12 | .03 | .20* | .09 | .16* | .29*** | .29*** | .15* | .17* | .40*** | .65*** | .40*** | .26** | – | ||

| 16. T2 Closeness | −.16* | .08 | .13 | −.03 | −.05 | −.06 | −.16* | −.05 | −.11 | −.10 | −.21** | −.18* | −.21** | −.13 | −.08 | – | |

| 17. T2 Conflict | .23** | .10 | .20** | .57*** | .63*** | .46*** | .50*** | .57*** | .70*** | .40*** | .39*** | .38*** | .28*** | .34*** | .21** | −.35*** | – |

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Mean | – | – | 9.17 | 0.49 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.61 | .17 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.71 | 0.86 | 0.47 | 0.83 | 3.79 | 1.65 |

| SD | – | – | 1.82 | 0.54 | 0.31 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.67 | .33 | 0.43 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.80 |

Note. For sex, 0=female, 1=male. For free/reduced lunch status, 0=student does not receive free/reduced lunch, 1=student receives free/reduced lunch. ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. ODD=oppositional defiant disorder. SCT=sluggish cognitive tempo. SR=child self-report. T1 = fall time point. T2 = spring time point (approximately 6 months after T1). TR=teacher-report.

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

Of the three dimensions on the CCI, Drowsy was significantly correlated with less closeness (r = −.21, p = .005), whereas Underactive and Daydreaming were not (rs = −.13 and −.08, ps = .097 and .30, respectively). However, Steiger’s z-tests indicated that there was no difference in the magnitude of the child-rated SCT dimensions in relation to student-teacher closeness (zs = 0.52 to 1.62; all ps > .05). Similarly, there were no significant differences among the child-rated SCT dimensions in their associations with student-teacher conflict (zs = 0.81 to 1.47; all ps > .05).

SCT in Relation to Student-Teacher Closeness

T1 teacher-rated SCT in relation to T2 closeness

As summarized in Table 2, no T1 mental health dimension entered on Step 1 was significantly associated with T2 student-teacher closeness. SCT, entered at Step 2, was significantly associated with less student-teacher closeness (β = −0.26, p = .02) above and beyond child age, sex, and the other mental health symptom dimensions. Above and beyond child age, sex, and other symptoms, T1 SCT accounted for 3% of the variance in predicting T2 student-teacher closeness. There was not a significant Sex × SCT interaction in predicting student-teacher closeness (p > .05).

Table 2.

Regression Analyses Examining Sluggish Cognitive Tempo in Relation to Student-Teacher Closeness

| Step 1

|

Step 2

|

Step 3

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Model Examining T1 Teacher-Rated SCT in Relation to T2 Student-Teacher Closeness | ||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| F(16,159)=2.17**, R2=.10 | F(1,158)=6.08*, R2 =.13, ΔR2=.03 | F(1,157)=1.38, R2=.13, ΔR2=.007 | ||||||||||

| Sex | −0.22 | 0.11 | −0.15 | −1.91 | −0.18 | 0.11 | −0.12 | −1.62 | −0.18 | 0.11 | −0.12 | −1.59 |

| T1 Age | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.16 | −0.62 | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.14 | −0.57 | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.16 | −0.63 |

| T1 ADHD | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 1.44 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 1.50 |

| T1 ODD/CD | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.29 | −0.01 | 0.22 | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.22 | 0.00 | −0.05 |

| T1 Internalizing | −0.11 | 0.18 | −0.06 | −0.62 | −0.04 | 0.17 | −0.02 | −0.23 | −0.05 | 0.17 | −0.03 | −0.31 |

| T1 SCT (TR) | – | – | – | – | −0.37 | 0.15 | −0.26 | −2.47* | −0.28 | 0.17 | −0.19 | −1.64 |

| Sex × T1 SCT (TR) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.26 | 0.23 | −0.11 | −1.18 |

| Model Examining T2 Child-Rated SCT in Relation to T2 Student-Teacher Closeness | ||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| F(2,173)=3.71*, R2=.03 | F(1,172)=0.40, R2=.03, ΔR2=.002 | F(1,172)=0.40, R2=.03, ΔR2=.002 | ||||||||||

| Sex | −0.23 | 0.11 | −0.16 | −2.09* | −0.22 | 0.11 | −0.15 | −2.00* | −0.22 | 0.11 | −0.15 | −1.98* |

| T2 Age | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 1.19 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 1.21 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 1.21 |

| T2 ADHD | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.68 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.95 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.77 |

| T2 ODD/CD | −0.04 | 0.20 | −0.02 | −0.21 | −0.05 | 0.20 | −0.02 | −0.25 | −0.06 | 0.20 | −0.03 | −0.28 |

| T2 Internalizing | −0.41 | 0.16 | −0.24 | −2.59* | −0.38 | 0.16 | −0.23 | −2.39* | −0.36 | 0.16 | −0.21 | −2.22* |

| T2 SCT (SR) | – | – | – | – | −0.11 | 0.12 | −0.08 | −0.92 | −0.03 | 0.16 | −0.02 | −0.21 |

| Sex × T2 SCT (SR) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.16 | 0.22 | −0.08 | −0.72 |

Note. For sex, 0=female, 1=male. Models included 11 dummy variables for the 12 teachers to control for the non-independence of observations. ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. ODD/CD=oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder. SCT=sluggish cognitive tempo. SR=child self-report. TR=teacher-report.

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

T2 child-rated SCT in relation to T2 closeness

In Step 1, male sex and T2 internalizing symptoms were both significantly associated with less student-teacher closeness (see Table 2). Child-rated SCT was not significantly associated with student-teacher closeness above and beyond age, sex, and teacher-rated mental health symptoms, nor was there a significant Sex × SCT interaction in predicting closeness (ps > .05).

SCT in Relation to Student-Teacher Conflict

T1 teacher-rated SCT in relation to T2 conflict

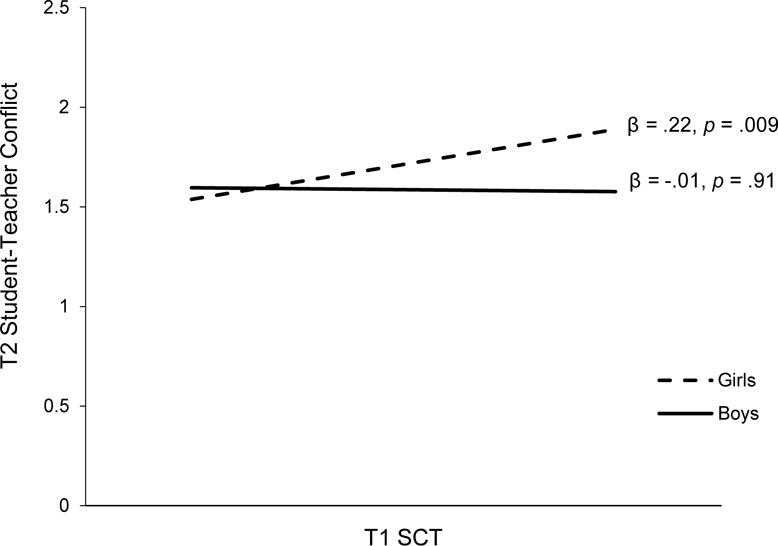

As summarized in Table 3, T1 ADHD and ODD/CD symptoms were both significantly associated with increased T2 student-teacher conflict above and beyond sex, age, and other mental health domains at T1. At Step 2, T1 SCT was not significantly associated with student-teacher conflict (β = 0.14, p = .07) above and beyond sex, age, and other mental health domains. However, a significant Sex × SCT interaction emerged in predicting student-teacher conflict (β = −0.14, p = .04). As shown in Figure 1, SCT was significantly positively associated with student-teacher conflict for girls (β = 0.22, p = .009) but not boys (β = −0.01, p = .91).2

Table 3.

Regression Analyses Examining Sluggish Cognitive Tempo in Relation to Student-Teacher Conflict

| Step 1

|

Step 2

|

Step 1

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Model Examining T1 Teacher-Rated SCT in Relation to T2 Student-Teacher Conflict | ||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| F(16,159) = 14.00***, R2 = .54 | F(1,158) = 3.41, R2 = .55, ΔR2 = .01 | F(1,157) = 4.33, R2 = .56, ΔR2 = .01 | ||||||||||

| Sex | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 1.61 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 1.39 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 1.46 |

| T1 Age | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.77 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.73 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.64 |

| T1 ADHD | 0.58 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 5.50*** | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 3.47*** | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 3.59*** |

| T1 ODD/CD | 0.93 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 5.35*** | 0.98 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 5.60*** | 0.98 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 5.68*** |

| T1 Internalizing | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.14 | −0.01 | −0.09 |

| T1 SCT (TR) | – | – | – | – | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 1.85 | 0.34 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 2.62* |

| Sex × T1 SCT (TR) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.36 | 0.17 | −0.14 | −2.08* |

| Model Examining T2 Child-Rated SCT in Relation to T2 Student-Teacher Conflict | ||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| F(16,158) = 19.92***, R2 = .64 | F(1,157) = 4.12*, R2 = .64, ΔR2 = .01 | F(1,156) = 0.01, R2 = .64, ΔR2 < .001 | ||||||||||

| Sex | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 2.18* | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 2.02* | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 2.01* |

| T2 Age | −0.14 | 0.07 | −0.32 | −1.90 | −0.14 | 0.07 | −0.33 | −1.97 | −0.14 | 0.07 | −0.33 | −1.96 |

| T2 ADHD | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 4.58*** | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 3.65*** | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 3.54** |

| T2 ODD/CD | 1.14 | 0.14 | 0.48 | 8.17*** | 1.16 | 0.14 | 0.49 | 8.33*** | 1.16 | 0.14 | 0.49 | 8.29*** |

| T2 Internalizing | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 1.59 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 1.24 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 1.22 |

| T2 SCT (SR) | – | – | – | – | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 2.03* | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 1.56 |

| Sex × T2 SCT (SR) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.01 | 0.15 | 0.00 | −0.07 |

Note. For sex, 0=female, 1=male. Models included 11 dummy variables for the 12 teachers to control for the non-independence of observations. ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. ODD/CD=oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder. SCT=sluggish cognitive tempo. SR=child self-report. TR=teacher-report.

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

Figure 1.

Sex Moderates the Relation between Teacher-Rated Sluggish Cognitive Tempo (fall time point; T1) and Student-Teacher Conflict (spring time point; T2) in Children.

T2 child-rated SCT in relation to T2 conflict

In Step 1, male sex, T2 ADHD symptoms, and T2 ODD/CD symptoms were each significantly associated with increased student-teacher conflict (see Table 3). Child-rated SCT, entered at Step 2, was significantly associated with increased conflict (β = 0.11, p = .04) above and beyond child age, sex, and the other mental health symptom dimensions. Above and beyond child age, sex, and teacher-rated symptoms, child-rated SCT accounted for 1% of the variance in predicting student-teacher conflict. The association between child-rated SCT and conflict was not moderated by sex (p > .05; see Table 3).

Exploratory Analyses Examining Child-Rated SCT Dimensions

When models were re-run to include the three child-rated SCT dimensions (instead of the total child-rated SCT score), none of the dimensions were significantly associated with either student-teacher closeness (βs = −0.09, 0.03, and −0.02 for Drowsy, Underactive, and Daydreaming, respectively; all ps > .05) or student-teacher conflict (βs = 0.09, 0.01, and 0.04 for Drowsy, Underactive, and Daydreaming, respectively; all ps > .05). Further, there were no significant interactions of any of the SCT dimensions with sex in relation to closeness or conflict (all ps > .05).

Discussion

This study extends previous research linking SCT to social difficulties and is the first to examine SCT in relation to the student-teacher relationship. Using a multi-informant, short-term longitudinal design, we found compelling support for our hypothesis that SCT would be uniquely associated with poorer student-teacher relationship quality. Specifically, teacher-rated SCT symptoms predicted less closeness six months later. Child-rated SCT was significantly associated with higher levels of student-teacher conflict concurrently (children did not rate their own SCT symptoms at T1 and so longitudinal analyses were not possible with child-rated SCT). Notably, these effects were found above and beyond child demographics and other mental health symptoms that were themselves significantly correlated with student-teacher relationship quality. Finally, the association between teacher-rated SCT and student-teacher conflict, both longitudinally and concurrently, was moderated by student sex such that SCT was associated with greater conflict for girls but not boys. This is the first study to examine the association between SCT and the student-teacher relationship and an important contribution to the accumulating evidence of associations between SCT and problems in school functioning (Bernad et al., 2014; Langberg et al., 2014).

In a recent meta-analysis, Becker and colleagues (2016) identified SCT as being more closely associated with symptoms of internalizing disorders than externalizing disorders. In this context, our findings are consistent with previous research that has examined the relations between mental health symptoms and the student-teacher relationship in children (Henricsson & Rydell, 2004; Murray & Murray, 2004). Specifically, Murray and Murray (2004) found that internalizing symptoms were more strongly negatively associated than externalizing symptoms with closeness and that externalizing symptoms were more strongly positively associated than internalizing symptoms with conflict after controlling for demographic factors and child motivation. Indeed, SCT and internalizing symptoms were the only mental health domains significantly associated with closeness in our study, and ODD/CD and ADHD symptoms were more strongly associated than SCT or internalizing symptoms with student-teacher conflict. Importantly, though SCT did not explain a large proportion of variance in student-teacher conflict and closeness, finding that SCT was uniquely associated with both conflict and closeness after controlling for other mental health symptoms and demographic characteristics is a stringent test that establishes SCT as an important area for future study as an incremental factor related to student-teacher conflict and closeness in conjunction with other child issues.

The measure of conflict in this study may point to one reason both externalizing and internalizing symptoms were associated with greater student-teacher conflict. The STRS conflict scale includes items describing the relationship as being difficult or draining to the teacher’s energy. These items could be rated equally highly for students with externalizing presentations who may exhibit poor self-control in social situations and students with internalizing presentations who may exhibit emotional lability or apathy. In considering SCT specifically, it is unclear what specific behaviors may contribute to the association of SCT with less closeness and conflict, as the magnitude of correlations between the SCT dimensions (Drowsy, Underactive, or Daydreaming) and conflict/closeness were similar and none of the three SCT dimensions were independently associated with student-teacher conflict or closeness. It thus appears that SCT as a whole – as opposed to any specific component – contributes to poorer student-teacher relationship quality. However, additional studies with larger sample sizes and different measures of SCT may be needed to uncover possible differential associations. Specifically, it is unclear whether our ability to detect effects by individual dimensions was limited by the scope of the Underactive (three items) and Daydreaming (two items) dimensions using the current measure. In addition, to inform treatment considerations and school-based services that may help to address student-teacher relationship concerns, it will be important for future research to more systematically examine the nuanced classroom behaviors that contribute to difficulties in student-teacher closeness and conflict.

The finding that SCT – when rated by teachers – was associated with greater student-teacher conflict for girls but not boys is important to note. Although preliminary, it is noteworthy that girls who exhibit similar SCT behaviors to boys may be at increased risk for student-teacher conflict. Although our study cannot answer why this difference occurred, socialization and differential teacher response to similar behavior exhibited by boys and girls may be one explanation. Girls are traditionally expected to be compliant, attentive, and socially competent, whereas boys are expected to be assertive, disruptive, and more inattentive (Carpenter, et al., 1986; Jones & Myhill, 2004; Serbin, et al., 1973). As such, a boy who exhibits sluggish, confused behavior may not be a source of conflict because he is being compared to boys perceived as disruptive or defiant and symptoms of SCT are not seen as particularly concerning compared to these behaviors. However, in girls, SCT may be perceived more negatively and be treated as a source of conflict and frustration because girls with SCT are being compared to how girls “should” act (Kokkinos et al., 2005). That this interaction was only found when teachers rated SCT lends support to this hypothesis. Future research using vignette designs that only vary sex but describe the same behaviors could help to disentangle this finding, as could classroom observations of student behavior and teacher responses.

It is increasingly clear that SCT is related to important academic and socioemotional aspects of school success and is associated with impairment in these areas above and beyond other mental health symptoms. Externalizing behavior and aggression are often primary factors in referring children for school-based services (Becker et al., 2014), yet students with SCT are likely to show withdrawn behaviors (Becker, Garner et al., 2017). These children may be at unique risk for long-term negative outcomes because their presentation may contribute to under-identification or “slipping through the cracks.” For now, school-based mental health providers would benefit from gaining knowledge about SCT and its symptoms and differences from other common mental health problems. Currently, no interventions that directly address SCT symptoms and associated impairments have been developed or evaluated; thus, it is recommended that interventions shown effective for associated impairment (i.e., coaching teachers in relationship building strategies, academic interventions) be implemented while effective interventions are developed and evaluated.

It will also be important for future research to continue to examine the measurement of SCT. Based on meta-analytic findings (Becker et al., 2016), a standard symptom set for assessing SCT in children is emerging (Becker, Burns et al., 2017; Sáez et al., 2017) that will allow for systematic assessment of SCT in the school setting. Yet, our study found that a single dimension of SCT best fit the data when SCT was rated by teachers and a three-factor solution best first the data when SCT was rated by children. Further, the child-rated SCT mean (0.71) was almost twice the mean of T1 teacher-rated SCT (0.38), also pointing to potential rater differences in SCT that will be important to examine in the future. There are not yet agreed upon cutoffs for SCT and future efforts may consider whether different cutoffs are necessary for different informants. Continuing to examine the consistency of factor structures across raters and populations and examining levels of SCT within these groups will help to move toward consensus on the measurement of SCT and will be important in determining distinct relationships between SCT and educational functioning (Becker, Burns, et al., 2017; Fenollar Cortés et al., 2017; Penny et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2016). For example, we used the SCT items that demonstrated empirical support in a recent meta-analysis, yet recent research indicates that the “unmotivated” item, which did not load on any of the specific child-rated SCT factors in the present study, is not an optimal SCT item across informants (Becker, Burns et al., 2017; Sáez et al., 2017). These emerging findings underscore the need to carefully refine and define the SCT construct as the field continues to advance.

Findings should be considered with several limitations in mind. First, the sample size was relatively small. It is encouraging that findings were detected across concurrent and prospective analyses, and across raters in the case of student-teacher conflict, but these initial results underscore the need for future studies with larger, more diverse samples. Second, the study only examined the student-teacher relationship in the elementary school context. As such, future studies with a larger developmental range should investigate the consistency of the association between SCT and the student-teacher relationship across the educational span and between teachers. Third, this study focused on a unidirectional path from SCT symptoms to the student-teacher relationship. As the student-teacher relationship is an interpersonal interaction over time, future studies should use analyses that examine the bidirectional, potentially cascading associations between SCT and the student-teacher relationship. Fourth, to comprehensively describe the context for the relationship between SCT symptoms and student-teacher conflict, future research should explore teacher characteristics (e.g., years teaching, teaching self-efficacy) that may serve as predictors of this association (Mashburn, Hamre, Downer, & Pianta, 2006). Similarly, all teachers in this study were female, and so we were unable to examine associations based on sex of the teacher. Finally, since a nonclinical sample was used in this study, findings may not generalize to clinical samples or children referred for educational services.

In conclusion, findings from the present study provide preliminary evidence that SCT symptoms are associated with student-teacher conflict and less student-teacher closeness above and beyond relevant demographic factors and other mental health symptoms. These associations appear robust, as results were generally consistent prospectively, concurrently, and as rated by both students and teachers. Notably, teacher-rated SCT was only associated with increased student-teacher conflict for girls and not boys, underscoring the importance of understanding how similar behavioral and symptom profiles for boys and girls may interact with the educational environment to produce differential results and, possibly, differential need for school-based supports. As the majority of students with mental health concerns receive their services in schools (Burns et al., 1995), school psychologists and school-based mental health providers are likely to emerge as critical partners in clarifying the need for intervention in the school setting for this population and uncovering and applying effective interventions to mitigate negative outcomes.

Impact and Implications.

SCT symptoms are uniquely associated with poorer student-relationship quality. SCT is unassessed in schools and may be important for both school-based screening and intervention efforts.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a scholarship to Stephen Becker from the American Psychological Foundation (APF) and the Council of Graduate Departments of Psychology (COGDOP). Stephen Becker is currently supported by award number K23MH108603 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the APF, COGDOP, or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

EFA with the teacher-rated SCT items at T2 yielded almost identical results (eigenvalue = 8.05; all factor loadings >0.60 [range: 0.82 to 0.97]) and supported a single factor of teacher-rated SCT.

Results were very similar when examining T2 teacher-rated SCT in relation to student-teacher closeness and conflict (concurrent analyses at the spring time point). T2 SCT was the only psychopathology dimension significantly associated with less closeness (β = −.30, p = .002), and there was not a significant sex × SCT interaction in relation to closeness. Both T2 ODD/CD symptoms and ADHD symptoms were uniquely associated with greater conflict, and a significant Sex × SCT interaction emerged in relation to conflict (β = −.17, p = .005). As in the longitudinal analyses, SCT was significantly positively associated with student-teacher conflict for girls (β = 0.15, p = .03) but not boys (β = −0.13, p = .16).

References

- Arbeau KA, Coplan RJ, Weeks M. Shyness, teacher-child relationships, and socio-emotional adjustment in grade 1. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34:259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Baker JA, Grant S, Morlock L. The teacher-student relationship as a developmental context for children with internalizing or externalizing behavior problems. School Psychology Quarterly. 2008;23:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Distinguishing sluggish cognitive tempo from ADHD in children and adolescents: executive functioning, impairment, and comorbidity. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42:161–173. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.734259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP. Sluggish cognitive tempo and peer functioning in school-aged children: a six-month longitudinal study. Psychiatry Research. 2014;217:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Burns GL, Schmitt AP, Epstein JN, Tamm L. Toward establishing a standard symptom set for assessing sluggish cognitive tempo in children: Evidence from teacher ratings in a community sample. Advance online publication. Assessment. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1073191117715732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Fite PJ, Garner AA, Greening L, Stoppelbein L, Luebbe AM. Reward and punishment sensitivity are differentially associated with ADHD and sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms in children. Journal of Research in Personality. 2013;47:719–727. [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Garner AA, Tamm L, Antonini TN, Epstein JN. Honing in on the social difficulties associated with sluggish cognitive tempo in children: Withdrawal, peer ignoring, and low engagement. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2017 doi: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1286595. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Leopold DR, Burns GL, Jarrett MA, Langberg JM, Marshall SA, Willcutt EG. The internal, external, and diagnostic validity of sluggish cognitive tempo: A meta-analysis and critical review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;55:163–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Luebbe AM, Fite PJ, Stoppelbein L, Greening L. Sluggish cognitive tempo in psychiatrically hospitalized children: Factor structure and relations to internalizing symptoms, social problems, and observed behavioral dysregulation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:49–62. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9719-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Luebbe AM, Joyce AM. The Child Concentration Inventory (CCI): Initial validation of a child self-report measure of sluggish cognitive tempo. Psychological Assessment. 2015;27:1037–1052. doi: 10.1037/pas0000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernad M, Servera M, Grases G, Collado S, Burns GL. A cross-sectional and longitudinal investigation of the external correlates of sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD-inattention symptoms dimensions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:1225–1236. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9866-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. Children’s interpersonal behaviors and the teacher-child relationship. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:934–946. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Angold A, Tweed D, Stangl D, Farmer EM, Erkanli A. Children’s mental health service use across service sectors. Health Affairs. 1995;14:147–159. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter CJ, Huston AC, Holt W. Modification of preschool sex-typed behaviors by participation in adult-structured activities. Sex Roles. 1986;14:603–615. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple correlation/regression analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fenollar Cortés J, Servera M, Becker SP, Burns GL. External validity of ADHD inattention and sluggish cognitive tempo dimensions in Spanish children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2017;21:655–666. doi: 10.1177/1087054714548033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano PA, Reavis RD, Keane SP, Calkins SD. The role of emotion regulation and children’s early academic success. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45:3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development. 2001;72:625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henricsson L, Rydell AM. Elementary school children with behavior problems: Teacher-child relations and self-perception. A prospective study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2004;50:111–138. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Myhill D. ‘Troublesome boys’ and ‘compliant girls’: gender identity and perceptions of achievement and underachievement. British Journal of Sociology of Education. 2004;25:547–561. [Google Scholar]

- Justice LM, Cottone EA, Mashburn A, Rimm-Kaufman SE. Relationships between teachers and preschoolers who are at risk: Contribution of children’s language skills, temperamentally based attributes, and gender. Early Education and Development. 2008;19:600–621. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinos CM, Panayiotou G, Davazoglou AM. Correlates of teacher appraisals of student behaviors. Psychology in the Schools. 2005;42:79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Birch SH, Buhs ES. Children’s social and scholastic lives in kindergarten: Related spheres of influence? Child Development. 1999;70:1373–1400. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Becker SP, Dvorsky MR. The association between sluggish cognitive tempo and academic functioning in youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:91–103. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9722-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaper C, Friedman CK. The socialization of gender. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, editors. Handbook of socialization: Theory and research. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 561–587. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SA, Evans SW, Eiraldi RB, Becker SP, Power TJ. Social and academic impairment in youth with ADHD, predominately inattentive type and sluggish cognitive tempo. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:77–90. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashburn AJ, Hamre BK, Downer JT, Pianta RC. Teacher and classroom characteristics associated with teachers’ ratings of prekindergartners’ relationships and behaviors. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2006;24:367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Meisinger RE, Lefler EK. Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of sluggish cognitive tempo. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorders. 2017;9:89–100. doi: 10.1007/s12402-016-0207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami AY, Huang-Pollock CL, Pfiffner LJ, McBurnett K, Hangai D. Social skills differences among attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder types in a chat room assessment task. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:509–521. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, Murray KM. Child level correlates of teacher-student relationships: An examination of demographic characteristics, academic orientations, and behavioral orientations. Psychology in the Schools. 2004;41:751–762. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK. Example for type=complex. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.statmodel.com/discussion/messages/12/776.html?1491090688.

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Eigth. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Penny AM, Waschbusch DA, Klein RM, Corkum P, Eskes G. Developing a measure of sluggish cognitive tempo for children: Content validity, factor structure, and reliability. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:380–389. doi: 10.1037/a0016600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC. Student-Teacher Relationship Scale. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Nimetz SL, Bennett E. Mother-child relationships, teacher-child relationships, and school outcomes in preschool and kindergarten. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1997;12:263–280. [Google Scholar]

- Roorda DL, Koomen HMY, Spilt JL, Oort FJ. The influence of affective teacher-student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Review of Educational Research. 2011;81:493–529. [Google Scholar]

- Serbin LA, O’Leary KD, Kent RN, Tonick IJ. Comparison of teacher response to preacademic and problem behavior of boys and girls. Child Development. 1973;44:796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Belmont MJ. Motivation in the classroom - reciprocal effects of teacher-behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1993;85:571–581. [Google Scholar]

- Smith ZR, Becker SP, Garner AA, Rudolph CW, Molitor SJ, Oddo LE, Langberg JM. Evaluating the structure of sluggish cognitive tempo using confirmatory factor analytic and bifactor modeling with parent and youth ratings. Assessment. 2018;25:99–111. doi: 10.1177/1073191116653471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ZR, Langberg JM. Predicting academic impairment and internalizing psychopathology using a multidimensional framework of Sluggish Cognitive Tempo with parent-and adolescent reports. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2017;26:1141–1150. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-1003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanless SB, McClelland MM, Lan XZ, Son SH, Cameron CE, Morrison FJ, Sung M. Gender differences in behavioral regulation in four societies: The United States, Taiwan, South Korea, and China. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2013;28:621–633. [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Chhabildas N, Kinnear M, DeFries JC, Olson RK, Leopold DR, Pennington BF. The internal and external validity of sluggish cognitive tempo and its relation with DSM-IV ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:21–35. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9800-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolraich ML, Bard DE, Neas B, Doffing M, Beck L. The psychometric properties of the Vanderbilt Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Diagnostic Teacher Rating Scale in a community population. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2013;34:83–93. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31827d55c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]