Abstract

Aim

To examine relationships among combat exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, depression, suicidality, nicotine dependence, and religiosity in Croatian veterans.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used Combat Exposure Scale (CES) to quantify the stressor severity, PTSD Checklist 5 (PCL) to quantify PTSD severity, Duke University Religion Index to quantify religiosity, Montgomery Asberg (MADRS) and Hamilton Depression (HAM-D) rating scales to measure depression/suicidality, and Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence to assess nicotine dependence. Zero-order correlations, cluster analysis, multivariate regression, and mediation models were used for data analysis.

Results

Of 69 patients included, 71% met “high religiosity” criteria and 29% had moderate/high nicotine dependence. PTSD was severe (median PCL 71), depression was mild/moderate (median MADRS 19, HAM-D 14), while suicidality was mild. A subset of patients was identified with more severe PTSD/depression/suicidality and nicotine dependence (all P < 0.001). Two “chains” of direct and indirect independent associations were detected. Higher CES was associated with higher level of re-experiencing and, through re-experiencing, with higher negativity and hyperarousal. It also showed “downstream” division into two arms, one including a direct and indirect association with higher depression and lower probability of high religiosity, and the other including associations with higher suicidality and lower probability of high nicotine dependence.

Conclusions

Psychopathology, religiosity, and nicotine dependence are intertwined in a complex way not detectable by simple direct associations. Heavy smoking might be a marker of severe PTSD psychopathology, while spirituality might be targeted in attempts of its alleviation.

Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine level of evidence: 3

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) results from severe stressful experience(s) during traumatic events, such as war operations. According to the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), it is characterized by re-experiencing of stressful events (cluster B), avoidance of trauma-related stimuli (cluster C), negative thoughts or feelings (cluster D) and hyperarousal (cluster E) (1). Severity of the combat experience is largely thought to determine the severity of PTSD symptoms (2-6), but findings have been inconsistent (7). However, most studies did not account for co-existing depression, although nearly 50% of the war veterans with PTSD had it as the most common comorbid disorder in PTSD (8-10). While PTSD might be a risk factor for (subsequent) development of depression (10), it is unclear whether the conditions tend to amplify each other, ie, the more severe PTSD, the more severe depression (11), or not (9).

Two phenomena have been extensively investigated in relation to PTSD psychopathology: smoking, or nicotine dependence, and religiosity. Prevalence of smoking is higher in PTSD patients including Croatian (12,13) or other war veterans (14,15) than in the general population and more intense smoking is associated with more severe symptoms (15-18). The association between PTSD and smoking seems to be bidirectional. Patients might smoke in an attempt to self-medicate to reduce tension and negative affect and symptoms after exposure to a trauma-related context (19). Prospective studies in stress-exposed individuals suggested smoking as a risk factor for developing PTSD symptoms (20), as it might potentiate or maintain maladaptive responses (21). Religiosity might also play a role in coping with the traumatic stress, given that life-threatening situations may change beliefs about existential meaning (22), which is why war veterans might exhibit different religious assumptions and practices than the general population (23).

Religiosity is a complex construct that may have opposite effects on health depending on the pattern of spiritual coping (24,25). Higher religious moral beliefs were beneficial to war veterans (17), whereas weakened religious faith and negative coping were associated with higher use of mental health services, more severe psychopathology, and suicidality (22,24). However, most studies have evaluated only individual relationship between PTSD and depression, smoking or dependence, and religiosity, without accounting for other factors intertwined with PTSD psychopathology. We assumed that considering all these factors in a stepwise analytical process accounting for confounding and possible moderating or mediating effects would improve our understanding of the complex nature of their inter-relationships. Out aim was to explore the relationships between severity of the core PTSD symptoms (overall and by clusters), depression, suicidality, religious involvement, and smoking in a sample of Croatian Homeland war veterans with combat-related PTSD.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This exploratory cross-sectional study was conducted between November 2017 and May 2018 at the University Hospital Center Zagreb and University Hospital Vrapče, Zagreb, which are among the largest national centers providing care for the Croatian Homeland war veterans with PTSD. Although thousands have been treated since 1991, at the time of the study, approximately 350-400 was veterans with combat experience had been under regular psychiatric treatment or follow-up (monthly or temporarily hospitalized) for ≥2 years. Those treated by the authors (MŠ, AMP, BVĆ, MV) were the candidates for inclusion.

Patients

The study included consecutive male patients who met the following criteria: verified PTSD diagnosed in line with the DSM-5; age ≤65 years; and signed informed consent. For the purpose of the study, all patients were re-evaluated using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (26) to confirm the diagnosis and presence of the exclusion criteria, which included dementia, intellectual disability or any other severe cognitive impairment, lifetime history of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective or delusional disorder, and alcohol or drug dependence in the previous six months. At the time of the study, all patients were attending supportive psychotherapy and received pharmacological treatments consisting mainly of selective serotonin or dual reuptake inhibitors and/or benzodiazepines and, sporadically, low-dose quetiapine, promazine or olanzapine at bedtime.

Method

PTSD severity. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) is a validated self-reporting instrument that quantifies symptom severity overall and by the four PTSD clusters consisting of re-experiencing stressful stimuli (PCL-B), avoidance of trauma-related stimuli (PCL-C), negative thoughts or feelings (PCL-D), and hyperarousal (PCL-E). Higher scores (minimum 17, maximum 85) indicate worse symptoms (27).

Severity of stressful stimulus. Combat Exposure Scale (CES) is a validated self-administered instrument where higher scores (minimum 0, maximum 41) indicate more severe past combat-related stressful stimuli (28).

Depression and suicidality. Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (29) and the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (30) are validated clinician-administered tools that quantify depressive difficulties over the past week. MADRS consists of 10 items (item 10 pertaining to suicidal thoughts) and HAM-D consists of 17 items (item 3 pertaining to suicidal thoughts). Higher scores (0-60 by MADRS, 0-52 by HAM-D) indicate more severe depression.

Religiosity. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL) is a validated self-administered instrument for quantification of basic religious or spiritual traits testing for “organizational” religious activity (ORA), “non-organizational” religious activity (NORA), and intrinsic religiosity (IR) (31,32). Higher scores (minimum 5, maximum 27) indicate more intense religiosity.

Smoking or nicotine dependence. The Fagerstrom Test for nicotine dependence (FTND) is a validated self-administered instrument that quantifies the mode and extent of cigarette smoking (33). It categorizes the level of nicotine dependence as low, low-moderate, moderate, or high.

Outcome measures. The outcome measures for PTSD included total PCL score, scores on each of its clusters, and total CES score. The outcome measures for depression included total MADRS and total HAM-D scores and separately MADRS score without item 10 and HAM-D without item, and intensity of suicidal thoughts. MADRS item 10 and HAM-D item 3 address the same characteristic, but use different wording and different scoring of the answers. Therefore, MADRS item 10 and HAM-D item 3 were summed-up to represent a single measure of suicidality. The outcome measures for religiosity consisted of total DUREL score and ORA, NORA, and IR subscores. Patients were dichotomized as those with high (ORA score ≥4, NORA score ≥4, IR score ≥10) and non-high overall religiosity (31,32). Finally, patients were classified as either current smokers or non-smokers, and nicotine dependence was classified as none or low and moderate or high.

Statistical analysis

Considering the exploratory nature of the study, data were analyzed in several steps. First, zero-order correlations (non-parametric Kendall’s correlation) were assessed between different outcome measures and cluster analysis was performed to screen for potential associations. Then, independent associations were identified using multivariate analysis of variance and logistic regression. Finally, based on these analyses, hypotheses were generated about inter-relationships that were evaluated using multivariate mediator models. We used SAS 9.4 for Windows (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA) software licensed to the University of Zagreb School of Medicine for data analysis.

RESULTS

Of 117 screened patients, 11 refused to participate and 37 suffered psychotic episodes, alcohol abuse, or bipolar disorder. Of 69 patients included in the study, 71% met the criterion of high religiosity, 46% were regular smokers, and 29% had a moderate or high nicotine dependence (Table 1). PTSD symptoms were severe, whereas overall depression severity was moderate. The intensity of suicidal thoughts was mild and 25% of patients had previous suicidal attempts.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 69 patients with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

| Characteristic | No. (%) of patients |

|---|---|

| Age (median, range; years) |

55 (39-65) |

| Marital status |

|

| single |

4 (5.8) |

| married |

58 (84.1) |

| widowed |

2 (2.9) |

| divorced |

5 (7.3) |

| Have children |

57 (82.6) |

| Employment status |

|

| unemployed |

16 (23.2) |

| employed |

25 (36.3) |

| retired |

28 (40.6) |

| Education level (highest achieved) |

|

| elementary |

6 (8.7) |

| high school |

54 (78.3) |

| higher education |

9 (13.0) |

| PCL score (median, range) |

|

| PCL-B (re-experiencing) |

18 (5-25) |

| PCL-C (avoidance) |

8 (2-10) |

| PCL-D (negativity) |

23 (8-35) |

| PCL-E (hyperarousal) |

21 (7-30) |

| CES score (median, range) |

23 (9-32) |

| Depression (median, range) |

|

| MADRS score |

19 (3-36) |

| HAM-D score |

14 (1-25) |

| Suicidality (median, range) |

|

| MADRS without item 10 |

19 (3-35) |

| HAM-D without item 3 |

14 (1-24) |

| mean MADRS 10 + HAM-D 3† |

0.64 (0-8) |

| Attempted suicide |

17 (24.6) |

| Religiosity (median, range) |

|

| DUREL index score |

18 (0-27) |

| ORA DUREL subscale score |

3 (0-6) |

| NORA DUREL subscale score |

3 (0-6) |

| IR DUREL subscale score |

11 (0-15) |

| DUREL high religiosity |

49 (71.0) |

| Regular smoker |

32 (46.4) |

| Nicotine dependence |

|

| none |

41 (59.4) |

| low or low-to-moderate |

8 (11.6) |

| moderate |

12 (17.4) |

| high |

8 (11.6) |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity‡ |

31 (44.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (15.9) |

*CES – Combat Exposure Scale; DUREL – Duke University Religion Index; ORA – organizational religious activity subscale, NORA – non-organizational religious activity subscale, IR – intrinsic religiosity subscale; HAM-D – Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MADRS – Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; PCL – PTSD Check List (clusters B-E).

†Both MADRS and HAM-D scales quantify intensity of suicidal thoughts based on one question with different scoring. Some patients scored “0” on one scale and “1” on the other. Therefore, the sum of scores on these two scales was used.

‡Treated hypertension, any form of coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, arrhythmia, peripheral artery disease, or history of stroke or transitory ischemic attack.

Unadjusted associations

Higher DUREL score was associated with higher subscale scores and weakly with higher PCL-B score (Table 2). The same weak association with PCL-B was observed for ORA and NORA scores, but not for IR score. Neither DUREL nor any of its subscales were associated with any other measure. Higher CES was associated with higher total PCL and higher PCL-B and D, but not with PCL-C and E scores (Table 2). It was also weakly associated with higher MADRS score and higher nicotine dependence, but not with HAM-D score. Higher total PCL was associated with higher scores on its subscales, MADRS, HAM-D, suicidality, and nicotine dependence scores. PCL-B showed the same pattern, but it was not associated with PCL-C, while PCL-C was not associated with any other measure. Higher PCL-D and PCL-E were associated with higher depression (MADRS, HAM-D), suicidality, and nicotine dependence, whereas higher MADRS and HAM-D scores were associated with higher suicidality (Table 2).

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations (non-parametric) between measures of religiosity (DUREL, ORA, NORA, IR), combat exposure (CES), overall PTSD symptom severity (PCL) or severity of re-experiencing stressful events (PCL-B), avoidance of related stimuli (PCL-C), negativity (PCL-D), and hyperarousal (PCL-E), depression (MADRS, HAM-D), suicidality (sum of MADRS item 10 and HAM-D item 3 scores), and nicotine dependence (“nicotine” – the 5 levels of nicotine dependence were considered as an ordinal variable with values from 0 [none] to 4 [high])*†

| DUREL | ORA | NORA | IR | CES | PCL | PCL-B | PCL-C | PCL-D | PCL-E | MADRAS | HAM-D | Suicidality | Nicotine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DUREL | — | 0.689 | 0.717 | 0.799 | 0.064 | 0.084 | 0.210 | -0.050 | 0.115 | -0.023 | -0.049 | -0.089 | -0.024 | -0.008 |

| ORA | <0.001 | — | 0.582 | 0.527 | 0.004 | 0.038 | 0.163 | -0.055 | 0.022 | -0.041 | -0.107 | -0.076 | -0.046 | -0.095 |

| NORA | <0.001 | <0.001 | — | 0.503 | 0.061 | 0.147 | 0.256 | -0.006 | 0.163 | 0.040 | 0.021 | -0.045 | 0.078 | -0.086 |

| IR | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | — | 0.035 | 0.014 | 0.096 | -0.109 | 0.074 | -0.076 | -0.103 | -0.144 | -0.073 | 0.057 |

| CES | 0.456 | 0.970 | 0.505 | 0.687 | — | 0.230 | 0.351 | 0.038 | 0.209 | 0.132 | 0.177 | 0.094 | 0.031 | 0.193 |

| PCL | 0.321 | 0.677 | 0.101 | 0.871 | 0.007 | — | 0.536 | 0.336 | 0.751 | 0.703 | 0.490 | 0.454 | 0.287 | 0.383 |

| PCL-B | 0.015 | 0.079 | 0.005 | 0.278 | <0.001 | <0.001 | — | 0.127 | 0.361 | 0.367 | 0.292 | 0.292 | 0.245 | 0.198 |

| PCL-C | 0.586 | 0.574 | 0.947 | 0.240 | 0.674 | <0.001 | 0.167 | — | 0.271 | 0.222 | 0.085 | 0.093 | -0.003 | 0.169 |

| PCL-D | 0.178 | 0.811 | 0.072 | 0.394 | 0.015 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | — | 0.551 | 0.453 | 0.366 | 0.223 | 0.376 |

| PCL-E | 0.791 | 0.653 | 0.662 | 0.388 | 0.124 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.015 | <0.001 | — | 0.501 | 0.480 | 0.293 | 0.408 |

| MADRS | 0.567 | 0.245 | 0.819 | 0.241 | 0.040 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.351 | <0.001 | <0.001 | — | 0.692 | 0.575 | 0.129 |

| HAM-D | 0.302 | 0.314 | 0.620 | 0.100 | 0.276 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.310 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | — | 0.477 | 0.109 |

| Suicidality | 0.798 | 0.654 | 0.435 | 0.451 | 0.740 | 0.002 | 0.010 | 0.976 | 0.018 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | — | -0.081 |

| Nicotine | 0.930 | 0.358 | 0.399 | 0.558 | 0.045 | <0.001 | 0.040 | 0.096 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.179 | 0.256 | 0.442 | — |

*CES – Combat Exposure Scale, DUREL – Duke University Religion Index, ORA – organizational religious activity subscale, NORA – non-organizational religious activity subscale, IR – intrinsic religiosity subscale, HAM-D – Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, MADRS – Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, PCL –Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Check List (clusters B-E).

†Kendall’s correlation coefficients are given by row (open cells) and corresponding P values by column (shaded cells)*

Cluster analysis indicated Cluster 1 with 25 subjects and Cluster 2 with 44 subjects that were fully comparable regarding religiosity, but Cluster 2 subjects had considerably higher CES and all PCL scores, depression, suicidality, and nicotine dependence (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of cluster analysis for two clusters identified on the basis of combat exposure score), severity of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, severity of depression, and nicotine dependence level considered as an ordinal variable*†

| Cluster 1 (n = 25) | Cluster 2 (n = 44) | Cluster 2 - 1 (95% CI) | P‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Variables |

||||

| DUREL total score (overall religiosity) |

18.0 |

19.0 |

0.0 (-3.0 to 3.0) |

0.913 |

| ORA |

3.0 |

3.0 |

0.0 (-1.0 to 1.0) |

0.948 |

| NORA |

3.0 |

4.0 |

0.0 (0.0 to 1.0) |

0.282 |

| IR |

12.0 |

11.0 |

-1.0 (-3.0 to 1.0) |

0.415 |

| Level of religiosity based on total DUREL |

||||

| high |

19 (76.0) |

30 (68.2) |

-7.8 (-28.0 to 15.4) |

0.431 |

| non-high |

6 (24.0) |

14 (31.8) |

||

| CES |

20.0 |

24.0 |

4.0 (2.0 to 7.0) |

0.003 |

| Severity of PTSD |

||||

| PCL total score (overall) |

51.0 |

78.0 |

28.0 (22.0 to 33.0) |

<0.001 |

| PCL-B (re-experiencing) |

15.0 |

20.5 |

6.0 (3.0 to 8.0) |

<0.001 |

| PCL-C (avoidance) |

6.0 |

9.0 |

2.0 (0.0 to 4.0) |

0.003 |

| PCL-D (negativity) |

14.0 |

27.0 |

12.0 (9.0 to 15.0) |

<0.001 |

| PCL-E (hyperarousal) |

15.0 |

24.0 |

9.0 (7.0 to 11.0) |

<0.001 |

| Severity of depression |

||||

| MADRS total score |

12.0 |

23.0 |

10.0 (7.0 to 13.0) |

<0.001 |

| HAM-D total score |

9.0 |

17.0 |

7.0 (5.0 to 9.0) |

<0.001 |

| Suicidality |

||||

| MADRS score without item 10 |

12.0 |

22.0 |

9.0 (6.0 to 12) |

<0.001 |

| HAM-D score without item 3 |

9.0 |

16.0 |

6.0 (4.0 to 8.0) |

<0.001 |

| MARDS item 10+HAM-D item 3 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

0.0 (0.0 to 2.0) |

0.002 |

| Attempted suicide |

5 (20.0) |

12 (27.3) |

7.3 (-16.6 to 26.8) |

0.572 |

| Nicotine dependence |

||||

| ordinal |

0.0 |

1.0 |

0.0 (0.0 to 2.0) |

0.002 |

| categorical |

||||

| none or low |

24 (96.0) |

25 (56.8) |

-39.2 (-54.9 to -19.8) |

<0.001 |

| moderate/high | 1 (4.0) | 19 (43.2) | 18.2 (3.8 to 32.1) |

*CES – Combat Exposure Scale, DUREL – Duke University Religion Index, ORA – organizational religious activity subscale, NORA – non-organizational religious activity subscale, IR – intrinsic religiosity subscale, HAM-D – Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, MADRS – Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, PCL – posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Check List (clusters B-E).

†Depicted are median values for continuous variables or number with percentage of patients for nominal variables by cluster and difference between the two clusters.

‡Mann-Whitney test for median difference or proportion difference.

Independent associations

In a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), total PCL score, PLC subscores, MADRS, HAM-D (without suicidality), and suicidality scores were simultaneous dependent variables, while high religiosity (vs low), moderate or high nicotine dependence (vs none or low), CES, age, and cardiovascular comorbidity or DM were independent variables (Table 4). There was no clear association between high religiosity and PTSD or depression. Moderate or high nicotine dependence was associated with higher total PCL score and its cluster D (negativity) and cluster E (hyperarousal), but there was no apparent association with cluster B (re-experiencing) and C (avoidance) scores. Moderate or high nicotine dependence was also associated with higher HAM-D. Higher CES was associated with higher PCL-B and no other measure. When “nicotine dependence” was replaced by “current smoker”, there was no overall effect of smoking (not shown).

Table 4.

Summary of multivariate analysis of independent associations of high religiosity, moderate or high nicotine dependence, and combat exposure with severity of posttraumatic stress-disorder symptoms (total PCL and cluster subscores), depression (MADRS and HAM-D without suicidality items), and suicidality (adjusted for age and cardiovascular comorbidity or diabetes mellitus)*

| Religiosity | Nicotine dependence | Combat exposure score | Age | Cardiovascular comorbidity or DM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Variables |

high vs non-high |

moderate/ high vs none/low |

by 1 point |

by 1 year |

yes vs no |

| Overall effect†(P) |

0.127 |

<0.001 |

0.010 |

0.334 |

0.547 |

| Individual outcomes‡ (difference, 95% CI) |

|||||

| Total PCL score | 1.74 (-0.61, 9.52) | 16.0 (8.00, 24.0) | 0.43 (-0.22, 1.09) | -0.39 (-0.95, 0.16) | 4.18 (-2.84, 11.2) |

|

P |

0.678 |

<0.001 |

0.190 |

0.160 |

0.238 |

| PCL-B score | 1.09 (-1.22, 3.39) | 1.81 (-0.57, 4.18) | 0.31 (0.11, 0.50) | -0.09 (-0.25, 0.08) | 1.35 (-0.73, 3.43) |

|

P |

0.351 |

0.133 |

0.002 |

0.291 |

0.199 |

| PCL-C score | -0.83 (-2.24, 0.58) | 0.70 (-0.75, 2.16) | -0.01 (-0.13, 0.10) | -0.02 (-0.12, 0.08) | 0.93 (-0.35, 2.20) |

|

P |

0.245 |

0.336 |

0.817 |

0.645 |

0.151 |

| PCL-D score | 2.36 (-1.27, 5.98) | 7.28 (3.55, 11.0) | 0.18 (-0.13, 0.48) | -0.09 (-0.35, 0.17) | 0.47 (-2.80. 3.74) |

|

P |

0.199 |

<0.001 |

0.254 |

0.476 |

0.775 |

| PCL-E score | -0.72 (-3.51, 2.07) | 6.13 (3.26, 9.00) | -0.01 (-0.24, 0.22) | -0.17 (-0.37, 0.03) | 1.48 (-1.04, 3.99) |

|

P |

0.607 |

<0.001 |

0.928 |

0.090 |

0.245 |

| MADRS without item 10 | -1.15 (-4.81, 2.50) | 3.23 (-0.53,6.99) | 0.17 (-0.14, 0.48) | -0.14 (-0.40, 0.12) | 2.34 (-0.96, 5.63) |

|

P |

0.530 |

0.091 |

0.274 |

0.283 |

0.161 |

| HAM-D without item 3 | -1.91 (-4.59, 0.78) | 3.07 (0.30, 5.83) | 0.01 (-0.21, 0.24) | -0.05 (-0.24, 0.14) | 1.32 (-1.09, 3.75) |

|

P |

0.162 |

0.030 |

0.890 |

0.620 |

0.279 |

| Suicidal thoughts§ | -0.17 (-1.16, 0.83) | -0.67 (-1.69, 0.36) | 0.04 (-0.04, 0.12) | -0.02 (-0.09, 0.05) | 0.40 (-0.49, 1.29) |

| P | 0.735 | 0.197 | 0.340 | 0.497 | 0.378 |

*DM – diabetes mellitus, CI – confidence interval, HAM-D – Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (17 items), MADRS – Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, PCL – Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Check-List.

†Multivariate analysis of variance for total PCL score, PLC clusters, MADRS, HAM-D, and suicidal thoughts scores as simultaneous multiple dependent variables; nicotine dependence, religiosity, combat exposure scale score, age, and cardiovascular comorbidity or DM as independent variables. The P value refers to an overall effect of an independent variable on multiple dependent variables based on Pillai’s trace statistic.

‡By fitting general linear models separately to each individual outcome, with religiosity, nicotine dependence, combat exposure scale score, age and cardiovascular comorbidity or DM as independent variables.

§MADRS item 10 and HAM-D item 3 summed.

In a reverse analysis, religiosity and nicotine dependence were dependent variables in logistic regression. Independent variables included CES, PCL-B, PCL-D, and E summed, HAM-D, suicidality, age, cardiovascular comorbidity or DM, and religiosity in the analysis of nicotine dependence and vice-versa. Highly religious patients were less likely to have moderate or high nicotine dependence, whereas those with moderate or high nicotine dependence were less likely to be highly religious (Table 5). However, the estimates were imprecise due to limited sample size. Higher PCL-D+E was associated with higher odds of moderate or high nicotine dependence, while higher suicidality was associated with lower odds. Higher HAM-D score was associated with lower odds of high religiosity.

Table 5.

Summary of logistic regression analyses of high religiosity (vs non-high) and moderate or high nicotine dependence (vs none or low) outcomes*

| Moderate/high nicotine dep |

High religiosity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P |

| High religiosity |

0.25 (0.04-1.31) |

0.102 |

— |

— |

| Moderate/high nicotine dependence |

— |

— |

0.36 (0.06-1.81) |

0.212 |

| Combat exposure score |

1.12 (0.96-1.34) |

0.159 |

0.95 (0.83-1.06) |

0.365 |

| PCL re-experiencing (cluster B) |

0.99 (0.77-1.31) |

0.964 |

1.09 (0.94-1.29) |

0.254 |

| PCL negativity + hyperarousal (cluster D+E) |

1.24 (1.11-1.45) |

<0.001 |

1.05 (0.98-1.15) |

0.182 |

| HAM-D without item 3 |

1.01 (0.80-1.26) |

0.917 |

0.84 (0.71-0.98) |

0.025 |

| Suicidality (MADRS item 10 + HAM-D item 3) |

0.47 (0.19-0.83) |

0.005 |

0.95 (0.65-1.44) |

0.775 |

| Age (by 1 year) |

0.93 (0.82-1.05) |

0.250 |

0.92 (0.83-1.01) |

0.091 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity or DM | 1.74 (0.35-10.2) | 0.503 | 1.14 (0.34-3.84) | 0.829 |

*OR – odds ratio, CI – confidence interval, PCL – Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Check List, HAM-D – Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, MADRS – Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale, DM – diabetes mellitus.

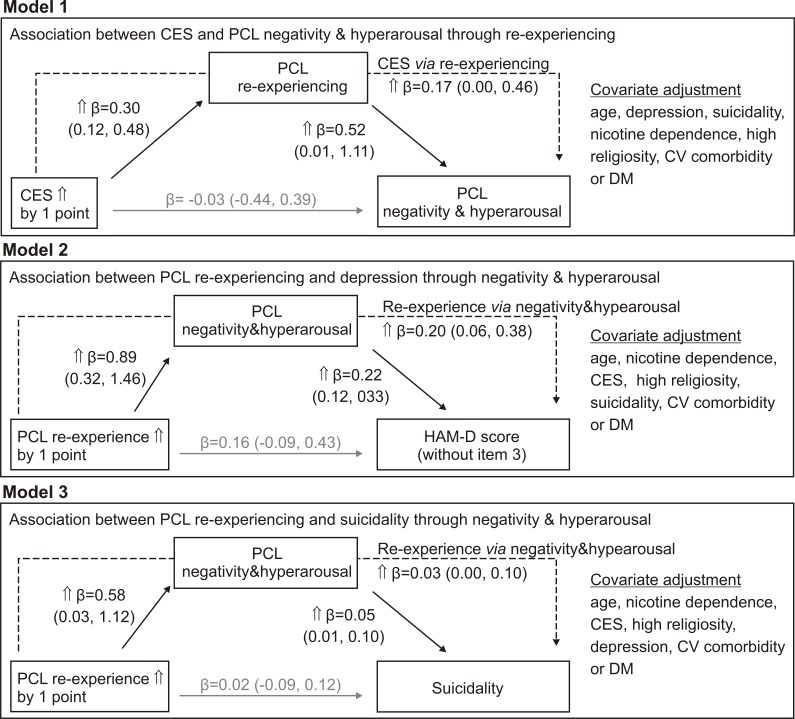

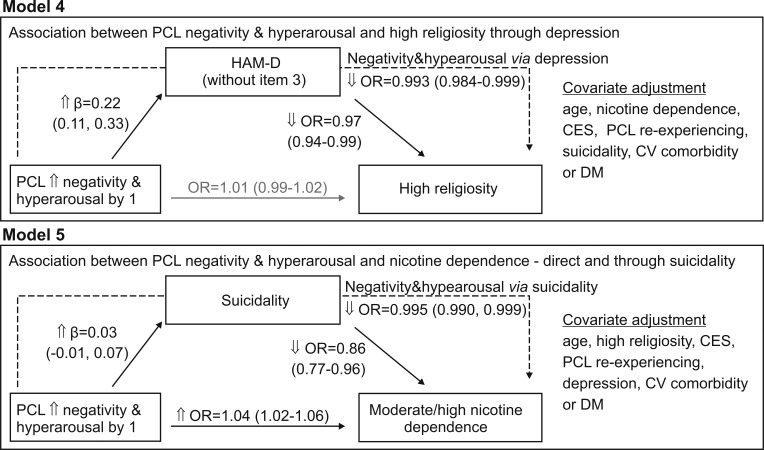

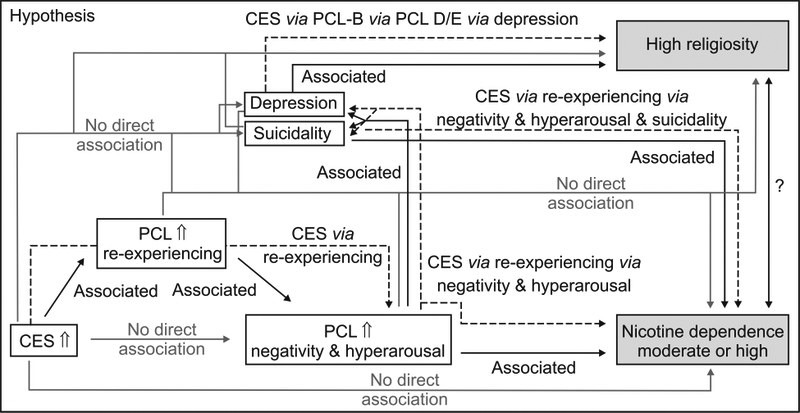

Based on the above observations, we hypothesized about direct and mediated associations (Figure 1). CES was a starting point for all hypotheses as follows: a) CES has no direct associations with depression, suicidality, negativity & hyperarousal (PCL-D+E), religiosity or nicotine dependence; b) higher CES is associated with higher re-experiencing (PCL-B); c) higher PCL-B is directly associated with higher PCL-D+E, but not with depression or suicidality, religiosity or nicotine dependence; d) association between CES and PCL-D+E is mediated through PCL-B; e) PCL-D+E has no direct association with religiosity, but it is directly associated with (i) nicotine dependence, hence CES or re-experiencing is associated with nicotine dependence through PCL-D+E, and (ii) depression and suicidality; f) depression has no direct association with nicotine dependence, but it is directly associated with religiosity, hence a mediation chain is CES/re-experiencing – PCL-D+E – depression – religiosity; g) suicidality has no direct association with religiosity, but it is directly associated with nicotine dependence, hence there are two mediation chains including (i) CES/re-experiencing – PCL-D+E – nicotine dependence and (ii) CES/re-experiencing – PCL-D+E – suicidality – nicotine dependence. To test these hypotheses, 5 models were fitted with the same variables: CES, PCL-B, PCL-D+E, HAM-D without suicidality (depression), suicidality, religiosity (high or non-high), nicotine dependence (moderate-high or none-low), age and cardiovascular comorbidity or DM. Independent, mediator, and dependent variables changed across the models (Figures 2 and 3). All associations, either direct or mediated, in each model were independent, adjusted for all other variables. In Model 1 (Figure 2), CES was an independent, PCL-B was a mediator, and PCL-D+E was a dependent variable, and all other variables were covariates. Higher CES was directly associated with higher PCL-B, but not with PCL-D+E; higher PCL-B was directly associated with higher PCL-D+E, hence higher CES was associated with higher PCL-D+E through PCL-B. The starting, independent variable in Model 2 and Model 3 was “shifted down the chain”, from CES (now a covariate) to PCL-B. In both models, higher PCL-B was directly associated with higher PCL-D+E, but not with depression (Model 2) or suicidality (Model 3) (Figure 2). Higher PCL-D+E was directly associated with higher depression (Model 2) or higher suicidality (Model 3). Therefore, in both models, there was a mediated association between PCL-B and the dependents (Figure 2). In Models 4 and 5, PCL-D+E was the independent, depression (Model 4) or suicidality (Model 5) were mediators, and high religiosity (Model 4) or moderate/high nicotine dependence (Model 5) were dependent varables (Figure 3). In Model 4, higher PCL-D+E was directly associated with higher depression, but not with high religiosity, and higher depression was directly associated with lower odds of high religiosity; hence, higher PCL-D+E was associated with lower odds of high religiosity through depression. In Model 5, higher PCL-D+E was directly associated with higher suicidality and higher odds of moderate or high nicotine dependence. Higher suicidality was directly associated with lower odds of moderate or high nicotine dependence; hence, higher PCL-D+E was associated with lower odds of moderate or high nicotine dependence through suicidality. Higher PCL-D+E was associated with moderate or high nicotine dependence in opposing ways, ie, with higher odds directly, and with lower odds through suicidality (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of sequential hypotheses about direct (full black lines/arrow) and a lack of direct (full gray lines/arrow) associations and about mediated (dashed black lines/arrows) associations between the intensity of stressful events (Combat Exposure Scale [CES] score,), intensity of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms assessed by the PTSD Check List (PCL), in particular re-experiencing stressful events (PCL-B score) and negativity&hyperarousal (PCL-D and E scores), depression, suicidality, high religiosity and nicotine dependence. See text for detailed hypothesis about a “direct/mediated association chain”. The chain is generated based on univariate (unadjusted) associations depicted in Table 2 and Table 3 (zero-order correlations and cluster analysis) and independent (adjusted) associations depicted in Table 4 and Table 5 (multivariate analysis of variance and logistic regression).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of mediation (based on multivariate regressions) models evaluating the hypotheses depicted in Figure 1: Models 1, 2 and 3. All models included the same variables as follows: combat exposure score (CES), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) check list (PCL) cluster B score (re-experiencing), PCL cluster D+E score (summed scores of negativity and hyperarousal), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score without item 3 (depression without suicidality), suicidality score (summed scores on HAM-D item 3 and Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale item 10), religiosity level (high or non-high), nicotine dependence (moderate/high or none/low), age and presence of cardiovascular comorbidity (CV) or diabetes mellitus (DM). The roles of “independent”, “mediator” or “dependent” variable or covariates, changed across the models. All possible associations – direct or mediated – are adjusted for all variables in the models hence all are “adjusted” or independent. Associations are expressed as regression coefficients (β) with 95% confidence intervals. Covariate effects on mediator or dependent variables are omitted for clarity. Fonts and lines/arrows (full for direct associations, dashed for mediated associations) in black depict coefficients (associations) different from zero. Gray font/lines depict coefficients not different from zero.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of mediation (based on multivariate regressions) models evaluating the hypotheses depicted in Figure 1: Models 4 and 5. All models included the same variables as follows: combat exposure score (CES), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) check list (PCL) cluster B score (re-experiencing), PCL cluster D+E score (summed scores of negativity and hyperarousal), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score without item 3 (depression without suicidality), suicidality score (summed scores on HAM-D item 3 and Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale item 10), religiosity level (high or non-high), nicotine dependence (moderate/high or none/low), age and presence of cardiovascular comorbidity (CV) or diabetes mellitus (DM). The roles of “independent”, “mediator” or “dependent” variable or covariates, changed across the models. All possible associations – direct or mediated – are adjusted for all variables in the models hence all are “adjusted” or independent. Associations are expressed either as regression coefficients (β) or as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Covariate effects on mediator or dependent variables are omitted for clarity. Fonts and lines/arrows (full for direct associations, dashed for mediated associations) in black depict coefficients/ORs (associations) different from zero/unity. Gray font/lines depict coefficients/ORs not different from zero/unity.

DISCUSSION

Combat experience and PTSD

Our results showed that PTSD is a chronic disorder that does not subside with time (6,34). Higher combat exposure was associated with more intense re-experiencing, negativity and hyperarousal, and depression, supporting the view that it predicts PTSD persistence (35). A previous study in Croatian veterans found that all PTSD symptoms were more severe with more intense war experience, but it did not assess depression and negativity and participants were exclusively prisoners of war (2). Different stressors impact PTSD clusters differently, eg, re-experience is associated with violent combat, but it does not seem to be associated with avoidance symptoms (3). In the present study, avoidance was not related to any measure, which is in line with the observations that avoidance changes over time, while re-experiencing remains stable (3). Avoidance seems to be linked to combat severity only early in the PTSD course, primarily in younger individuals, and the relationship might include alcohol dependence (3,5). Our study participants were middle-aged veterans without recent alcohol abuse or dependence. One previous report found no direct link between combat exposure and suicidal thoughts (11). Our findings suggest that suicidality is linked to traumatic experience indirectly, through re-experiencing, negativity, hyperarousal, and depression.

Nicotine dependence and psychopathology

We found a high smoking prevalence in our study participants, but the smoking status was not associated with PTSD severity, which is in line with previous findings (13). However, moderate or severe nicotine dependence was associated with more severe negativity, hyperarousal, and depression. This is also in agreement with several reports (15-17), particularly regarding hyperarousal symptoms (8,15,19).

We observed no association between nicotine dependence and core depression, but higher suicidality seemed to be associated with lower nicotine dependence. These two observations seem contradictory. Patients with more severe PTSD, depression, and suicidality also had a higher prevalence of moderate or high nicotine dependence, whereas higher suicidality scores were directly associated with lower odds of moderate or high nicotine dependence. However, cluster analysis does not control for confounding, whereas regression analyses detect independent associations. Also, the association between suicidality and nicotine dependence is not only a direct one. Our Model 5 showed that higher negativity and hyperarousal were directly associated with higher suicidality and moderate or high nicotine dependence and with lower odds of moderate or high nicotine dependence indirectly through their association with suicidality. Therefore, it is not surprising that higher negativity and hyperarousal, higher suicidality, and moderate or high nicotine dependence were clustered, but at a given level of negativity and hyperarousal, higher suicidality seemed to be associated with lower odds of moderate or high nicotine dependence. This finding seems counterintuitive given that tobacco use was repeatedly associated with suicidality (36-38). The question is whether smoking provokes suicidality or suicidal individuals smoke as a self-medication. In the present study, patients with higher disease severity, which itself is a stressor, had higher levels of nicotine dependence. Since the rewarding effects of nicotine are augmented after exposure to stressors, at least in animal models (39), nicotine might exert distinct effects in highly-stressed individuals with PTSD that decrease suicidality, but not other symptoms. Smoking cessation, in turn, might increase suicidality (36). None of our patients attempted to quit smoking at the time of the assessment.

Religiosity and psychopathology

In the US war veterans, different aspects of higher religiosity were associated with milder PTSD symptoms and depression (40,41). We also found that more severe depression (higher HAM-D without item 3) was associated with lower odds of high religious involvement (based on DUREL), while more intense PTSD symptoms (re-experiencing, negativity, and hyperarousal) were also associated with lower odds of high religiosity, albeit not directly as the association seemed to be mediated through depression. Studies in war veterans with PTSD reported inverse relationships between general religiosity and suicidality (42,43). These studies included generally more severely suicidal patients. We intentionally separated depression and suicidality, because core depression and suicidality have different clinical meaning and suicidality in our study sample was generally mild and minimally contributed to the overall depression scores. Both were evaluated in models with mutual adjustments. Under such circumstances, we observed no association between religiosity and suicidality; however, depression and suicidality were closely correlated. Our results suggest that in moderately depressed but mildly suicidal combat PTSD patients, high religiosity was primarily associated with (lower) depression and association with suicidality existed to the extent to which it was a part of overall depression.

Our exploratory analysis of complex constructs had several limitations. The exploratory nature particularly refers to mediation analysis which a priori implies causal relationships, while the study was cross-sectional. Due to a limited sample size, most estimates were imprecise. Furthermore, the cultural setting of the present study was specific as it evaluated relationship between religious involvement and psychopathology in war veterans 20 years after the end of the war that marked the beginning of a post-communist era. On the other hand, participants were enrolled consecutively based on restrictive criteria to enable evaluation of targeted psychopathology, ie, core PTSD and depression, and religious involvement and smoking. In combination with statistical adjustments, this approach allowed for a fair control of confounding, and the present observations could be considered internally valid to a reasonable extent. Although the sample size was limited a consequence of timing of the study and applied inclusion and exclusion criteria, we interpreted data with caution focusing on size of the “effects” and their direction. Finally, using CES score, albeit assessed retrospectively with susceptibility to recall bias, as a starting point in the mediation chains followed by PTSD elements, seemed to be psychodynamically justified. Under these circumstances, we observed a rather straightforward association between higher religious involvement and lower depression severity. The coexisting direct and mediated relationships were indicated between the severity of combat trauma, clusters of core PTSD (re-experiencing, negativity and hyperarousal), depression, and religious involvement on one hand, and suicidality and nicotine dependence, on the other. While the present work cannot exclude other possible relationships, the apparent ones deserve further evaluation.

In conclusion, our results suggest complex associations between war stressors, psychopathology, nicotine dependence, and religiosity in patients with combat-related PTSD. Specifically, direct and mediated associations seem to exist between severity of the past stimuli and different aspects of current psychopathology. If one is to perceive religiosity as spirituality, data suggest that treatments targeting individual’s spiritual resources could directly or indirectly improve the management of PTSD, which is in line with the currently suggested modifications of the standard cognitive processing therapies (44).

Acknowledgments

Funding None.

Ethical approval received from the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Center Zagreb on April 2017, number 02/21 AG, and Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Vrapče in Zagreb on May 2017, number 23/072/2-17.

Declaration of authorship BP and MŠ designed the study, BP, MŠ, and MV acquired the data. VT analyzed the data and BP, VT, MV, and VT interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript. All authors took the part in drafting of the manuscript, gave final approval, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™. 5th ed. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lončar M, Plašć ID, Bunjevac T, Hrabač P, Jakšić N, Kozina S, et al. Predicting symptom clusters of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Croatian war veterans: the role of socio-demographics, war experiences and subjective quality of life. Psychiatr Danub. 2014;26:231–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osório C, Jones N, Jones E, Robbins I, Wessely S, Greenberg N. Combat Experiences and their Relationship to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Clusters in UK Military Personnel Deployed to Afghanistan. Behav Med. 2018;44:131–40. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2017.1288606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox RC, McIntyre WA, Olatunji BO. Interactive Effects of Insomnia Symptoms and Trauma Exposure on PTSD: Examination of Symptom Specificity. Psychol Trauma. doi: 10.1037/tra0000336. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee J, Possemato K, Ouimette PC. Longitudinal changes in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder among operation enduring freedom/operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation New Dawn veterans with hazardous alcohol use: the role of avoidance coping. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205:805–8. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steenkamp MM, Schlenger WE, Corry N, Henn-Haase C, Qian M, Li M, et al. Predictors of PTSD 40 years after combat: Findings from the National Vietnam Veterans longitudinal study. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34:711–22. doi: 10.1002/da.22628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLean CP, Zang Y, Zandberg L, Bryan CJ, Gay N, Yarvis JS, et al. STRONG STAR Consortium Predictors of suicidal ideation among active duty military personnel with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:392–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joseph AM, McFall M, Saxon AJ, Chow BK, Leskela J, Dieperink ME, et al. Smoking intensity and severity of specific symptom clusters in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2012;25:10–6. doi: 10.1002/jts.21670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovacic Petrovic Z, Nedic Erjavec G, Nikolac Perkovic M, Peraica T, Pivac N. No association between the serotonin transporter linked polymorphic region polymorphism and severity of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in combat veterans with or without comorbid depression. Psychiatry Res. 2016;244:376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stander VA, Thomsen CJ, Highfill-McRoy RM. Etiology of depression comorbidity in combat-related PTSD: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryan CJ, Heron EA. Belonging protects against postdeployment depression in military personnel. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:349–55. doi: 10.1002/da.22372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jergović M, Bendelja K, Savić Mlakar A, Vojvoda V, Aberle N, Jovanovic T, et al. Circulating levels of hormones, lipids, and immune mediators in post-traumatic stress disorder - a 3-month follow-up study. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:49. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Svob Strac D, Kovacic Petrovic Z, Nikolac Perkovic M, Umolac D, Nedic Erjavec G, Pivac N. Platelet monoamine oxidase type B, MAOB intron 13 and MAOA-uVNTR polymorphism and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Stress. 2016;19:362–73. doi: 10.1080/10253890.2016.1174849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly MM, Jensen KP, Sofuoglu M. Co-occurring tobacco use and posttraumatic stress disorder: Smoking cessation treatment implications. Am J Addict. 2015;24:695–704. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook J, Jakupcak M, Rosenheck R, Fontana A, McFall M. Influence of PTSD symptom clusters on smoking status among help-seeking Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:1189–95. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Güloğlu B. Psychiatric symptoms of Turkish combat-injured non-professional veterans. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2016;7:29157. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v7.29157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasanović M, Pajević I. Religious moral beliefs as mental health protective factor of war veterans suffering from PTSD, depressiveness, anxiety, tobacco and alcohol abuse in comorbidity. Psychiatr Danub. 2010;22:203–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weaver TL, Cajdrić A, Jackson ER. Smoking patterns within a primary care sample of resettled Bosnian refugees. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10:407–14. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beckham JC, Kirby AC, Feldman ME, Hertzberg MA, Moore SD, Crawford AL, et al. Prevalence and correlates of heavy smoking in Vietnam veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Addict Behav. 1997;22:637–47. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(96)00071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Velden PG, Kleber RJ, Koenen KC. Smoking predicts posttraumatic stress symptoms among rescue workers: a prospective study of ambulance personnel involved in the Enschede Fireworks Disaster. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94:267–71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calhoun PS, Wagner HR, McClernon FJ, Lee S, Dennis MF, Vrana SR, et al. The effect of nicotine and trauma context on acoustic startle in smokers with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;215:379–89. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2144-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontana A, Rosenheck R. Trauma, change in strength of religious faith and mental health service use among veterans treated for PTSD. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:579–84. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000138224.17375.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mihaljević S, Aukst-Margetić B, Vuksan-Ćusa B, Koić E, Milošević M. Hopelessness, suicidality and religious coping in Croatian war veterans with PTSD. Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24:292–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witvliet CVD, Phipps KA, Feldman ME, Beckham JC. Posttraumatic mental and physical health correlates of forgiveness and religious coping in military veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17:269–73. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029270.47848.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith-MacDonald L, Norris JM, Raffin-Bouchal S, Sinclair S. Spirituality and mental well-being in combat veterans: a systematic review. Mil Med. 2017;182:e1920–40. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-17-00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, Spitzer RL. Structured clinical interview for DSM-5-Research Version (SCID-5 for DSM-5, Research Version; SCID-5-RV). Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). 2017. Available from: www.ptsd.va.gov. Accessed: September 7, 2018.

- 28.Keane T, Fairbank J, Caddell J, Zimering R, Taylor K, Mora C. The Combat Exposure Scale (CES) [Measurement instrument]; 1989. Available from: http://www.ptsd.va.gov. Accessed: September 7, 2018.

- 29.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koenig HG, Büssing A. The Duke university religion index (DUREL): a five-item measure for use in epidemological studies. Religions (Basel) 2010;1:78–85. doi: 10.3390/rel1010078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koenig HG, Meador KG, Parkerson G. Religion index for psychiatric research. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:885–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.885b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solomon Z, Levin Y, Assayag EB, Furman O, Shenhar-Tsarfaty S, Berliner S, et al. The implication of combat stress and PTSD trajectories in metabolic syndrome and elevated C-reactive protein levels: a longitudinal study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:1180–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bray RM, Engel CC, Williams J, Jaycox LH, Lane ME, Morgan JK, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in U.S. military primary care: trajectories and predictors of one-year prognosis. J Trauma Stress. 2016;29:340–8. doi: 10.1002/jts.22119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C. Tobacco use and 12-month suicidality among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19:39–48. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bronisch T, Höfler M, Lieb R. Smoking predicts suicidality: findings from a prospective community study. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:135–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilhelm K, Handley T, Reddy P. A case for identifying smoking in presentations to the emergency department with suicidality. Australas Psychiatry. 2018;26:176–80. doi: 10.1177/1039856218757638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biala G, Pekala K, Boguszewska-Czubara A, Michalak A, Kruk-Slomka M, Grot K, et al. Behavioral and biochemical impact of chronic unpredictable mild stress on the acquisition of nicotine conditioned place preference in rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55:3270–89. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0585-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berg G. The relationship between spiritual distress, PTSD and depression in Vietnam combat veterans. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2011;65:1–11. doi: 10.1177/154230501106500106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Currier JM, Holland JM, Drescher KD. Spirituality factors in the prediction of outcomes of PTSD treatment for U.S. military veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:57–64. doi: 10.1002/jts.21978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nađ S, Marčinko D, Vuksan-Ćusa B, Jakovljević M, Jakovljević G. Spiritual well-being, intrinsic religiosity, and suicidal behavior in predominantly catholic Croatian war veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder-a case control study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:79–83. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31815faa5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kopacz MS, Currier JM, Drescher KD, Pigeon WR. Suicidal behavior and spiritual functioning in a sample of veterans diagnosed with PTSD. J Inj Violence Res. 2016;8:6–14. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v8i1.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearce M, Haynes K, Rivera NR, Koenig HG. Spiritually integrated cognitive processing therapy: a new treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder that targets moral injury. Glob Adv Health Med. 2018;7:2164956118759939. doi: 10.1177/2164956118759939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]