Abstract

Circuit operations are determined jointly by the properties of the circuit elements and the properties of the connections among these elements. In the nervous system, neurons exhibit diverse morphologies and branching patterns, allowing rich compartmentalization within individual cells and complex synaptic interactions among groups of cells. In this review, we summarize work detailing how neuronal morphology impacts neural circuit function. In particular, we consider example neurons in the retina, cerebral cortex, and the stomatogastric ganglion of crustaceans. We also explore molecular coregulators of morphology and circuit function to begin bridging the gap between molecular and systems approaches. By identifying motifs in different systems, we move closer to understanding the structure-function relationships that are present in neural circuits.

Keywords: branching, development, morphology, tuning, wiring

INTRODUCTION

Over 150 years ago, Santiago Ramón y Cajal employed a new staining method, Golgi Cox labeling, which allowed him to observe the diverse morphologies of neurons for the first time. His observations, as well as the many gorgeous drawings of neuronal structure he produced, are still frequently commented on today. These observations led neuroscientists, including Ramón y Cajal himself, to question the incredible diversity of neuronal structure: How do neurons develop elaborate processes? What determines cell type-specific arborization characteristics? Do these structural differences contribute to the function of the neuron and the circuit? Though a good deal of progress has been made in characterizing the development of dendrites and dendritic spines, we still know relatively little about how a neuron’s specific morphology contributes to its function at the cellular level or how that in turn dictates how the cell integrates into a circuit.

Despite a somewhat limited understanding of how neuronal morphology may impact cellular or circuit function, alterations in dendritic complexity have been observed in a number of neuropsychiatric conditions and rodent models of disease (Belichenko et al. 2009; Kulkarni and Firestein 2012). Dendritic hypertrophy (abnormally large dendrites) has been observed in autism models (Belichenko et al. 2009; Jiang et al. 2013), whereas dendritic hypotrophy (abnormally small dendrites) has been observed in schizophrenia models (Gilmore et al. 2004; Kvajo et al. 2008) and in neural tissue isolated from people with Alzheimer’s disease (Cochran et al. 2014; Nalbantoglu et al. 1997). Dendritic complexity has also been shown to undergo remarkable remodeling when organisms are faced with environmental challenges, such as stressful experiences or early life adversity (reviewed in Fenoglio et al. 2006; McEwen 2003; Romeo and McEwen 2006; among many others). Interestingly, in the case of stress-induced remodeling, these dendritic changes have been correlated with behavioral outcome (Liston et al. 2006). However, we know relatively little about how these many possible morphological changes might relate to the cellular and circuit-level dysfunction observed in these conditions. It remains unclear whether changes in morphology underlie changes in circuit function, whether altered circuit function may lead to altered morphological properties, or whether these two processes occur in concert. The ability to determine whether morphological alterations are a symptom or a cause of disease has remained elusive for many years due to an inability to make careful measurements of both simultaneously and the lack of availability of molecular tools to manipulate these factors independently.

Technological limitations have historically made direct assessment of the relationship between neuronal structure and function difficult. However, recent advances in in vivo imaging techniques have allowed researchers to begin making these observations in intact circuits. The availability of reliable fluorescent calcium sensors and genetic tools for visualizing targeted cells combined with long-term imaging techniques enables the identification and characterization of neuronal morphology and function over time and in response to changes in sensory input. To make the most meaningful progress in this area, we must first consider the purposes that neuronal morphology serves, how morphology and circuit activity interact during development, and how structure and function may be coregulated across the lifespan. Although much of the characterization of the structure-function relationship remains to be performed, recent advances have made progress in understanding this fundamental problem in neuroscience. Much of this work has been performed in the visual cortex of mammalian species due to the high degree of physiological and anatomical characterization already present for this structure and the ease of altering sensory input. For that reason, we focus on the visual cortex with selected information collected from other regions.

CONTENT

What Are Common Principles and Functions of Branching Structures?

Biological systems often need to solve the spatial problem of delivering or receiving input from within densely packed cellular structures. In the human body, capillaries only 5–10 µm wide exchange oxygenated and deoxygenated blood in the outer reaches of the circulatory system (Sakai and Hosoyamada 2013). In each tissue, the exact architecture of the microcirculation vessels is tailored to the functional needs of that system (Sakai and Hosoyamada 2013). Even relatively modest changes in the architecture of small vessels are associated with diseases, such as hypertension (Heagerty et al. 1993) and Alzheimer’s disease (Hashimura et al. 1991). While the tiny diameter of these structures is critical for fitting into cell-dense regions, excellent vascular coverage of the surrounding tissue requires extensive branching of the capillaries. Indeed, the necessity for both small size and efficient spatial coverage may be one reason that branching structures are a commonly conserved structural motif in biological systems.

A striking example of multifunctional branching structures are neuronal dendrites. These structures make up ~35% of the total volume of the brain (Braitenberg and Schüz 1998), on par with the space occupied by axonal arbors (Braitenberg and Schüz 1998). Each dendrite is itself only a few micrometers in diameter, but the combined arbor of one cortical pyramidal neuron can span hundreds of micrometers across the cortex in the mouse and, on average, comprises ~3.5 mm of total material (Braitenberg and Schüz 1998). At the level of neurons, dendrites provide locations for synapses to form, are sites of translation (Bramham and Wells 2007; Eberwine et al. 2001), and determine how current flows within the cell, in terms of passive current flow (Agmon-Snir and Segev 1993), backpropagating action potentials (Stuart and Sakmann 1994), and locally generated N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) spikes (Johnston et al. 1996; Major et al. 2013; Schiller et al. 1997, 2000). The ability to serve each of these functions is critically tied to the architecture of the individual cell. However, there are notable differences in how neurons from different species and even different areas within the same brain have evolved to solve these problems.

The problem of providing optimal dendritic real estate for receiving signals (and in some cases sending them) is not a simple one and does not have a singular solution in all cases. One component of a good solution is to adequately fill a functionally relevant spatial volume (see Figs. 2 and 3) without creating a structure that is too metabolically demanding to properly maintain. In chordate species, this is further complicated by the need to maintain nervous systems that fit within the confines of a skeleton, thus preventing dendrites (and branching structures of all kinds) from reaching enormous proportions.

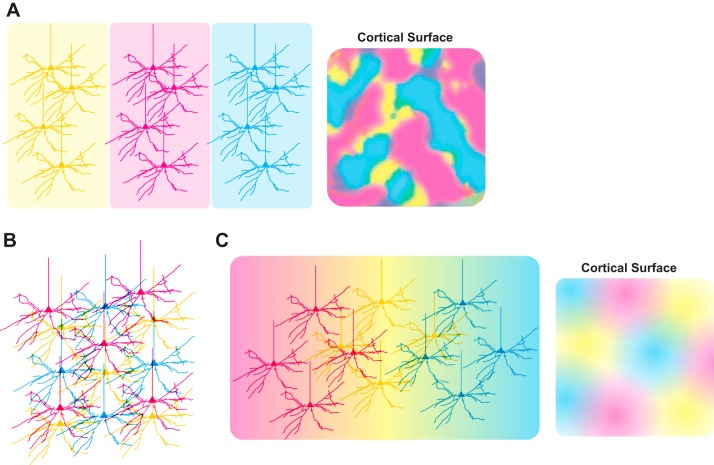

Fig. 2.

Structural and functional tiling at the circuit level in the cortex. A: the visual system of carnivores and primates is organized into segregated functional columns by receptive field property (left). Tiling and superposition of these columns (right), as opposed to dendritic arbors or individual neurons, allows each property to be represented at each retinotopic location in the cortex. B and C: the structural/functional organization of rodent visual cortex is not conclusively described. Evidence exists to suggest that subclasses of neurons sharing a receptive field property (magenta, yellow, and cyan cells) may tile the cortex at the individual cell level (B), similar to retinal tiling (Fig. 2B). Other evidence suggests loose spatial clustering of like-tuned cells (C) in a similar but less orderly organization than is found in carnivores and primates.

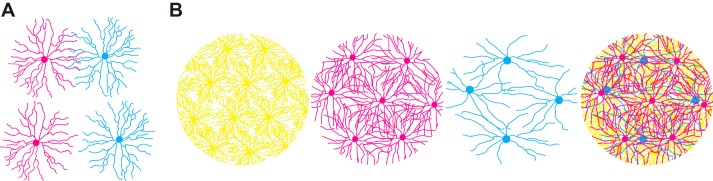

Fig. 3.

Structural and functional tiling at the circuit level in retina. A: overlap of starburst amacrine cell distal dendrites (top) is required for proper computation of direction of motion in the direction-selective circuit of the mouse retina. Overlapping starburst amacrine cells make GABAergic connections with each other that are involved in surround inhibition. Cells with nonoverlapping distal dendrites (bottom) do not have these reciprocal synapses. B: retinal ganglion cell (RGC) dendrites tile the retina with some overlap in dendritic fields (yellow, magenta, and cyan cells) and while maintaining regular spacing of somata. Hypothetical RGC subtypes (yellow, magenta, and cyan cells) have distinct morphologies and strategies for efficient tiling, requiring different arbor shapes and numbers of cells. Cells belonging to each of the hypothetical RGC subtypes are arranged randomly with respect to the other subtypes (far right).

Cellular-Level Strategies for Branching Structures

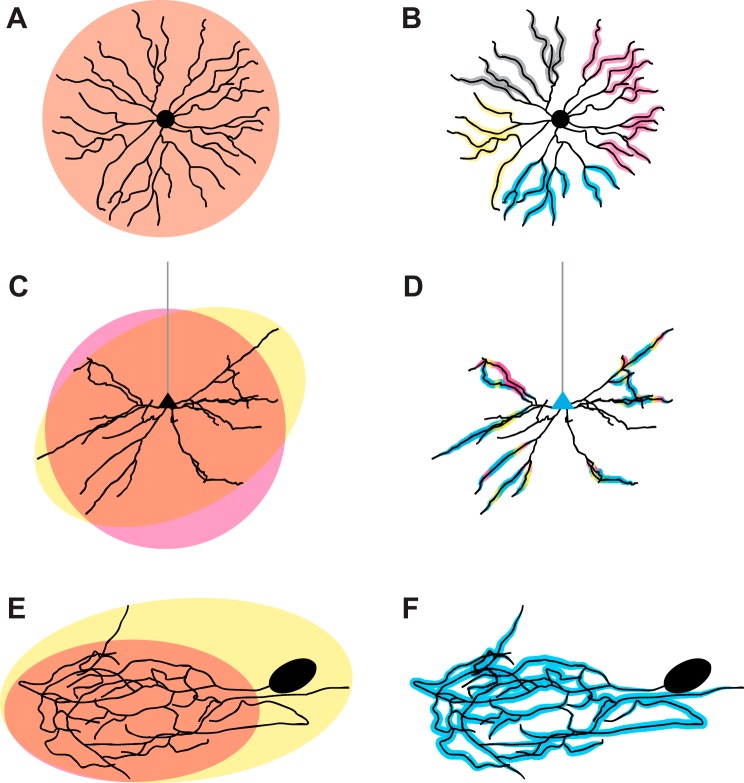

An elegant solution to these constraints exists in many cell types found in the mammalian retina (Anishchenko et al. 2010; Kolb et al. 1981; Wässle et al. 1981). One particularly interesting example is the starburst amacrine cell (Kolb et al. 1981; MacNeil and Masland 1998; Vaney 1990). To fit within the very thin retina (only ~0.3 mm in the thickest region of the human retina; Morse 1983), these neurons have developed nearly flat arbors (~5 µm thick; MacNeil et al. 1999) consisting primarily of a single layer of dendrites found in the inner plexiform layer (Seung and Sümbül 2014). The arbors of these cells are roughly circular from an en face perspective of the retina, and branch density is distributed relatively evenly over the space (Fig. 1A) (Kolb et al. 1981; MacNeil et al. 1999; Seung and Sümbül 2014). To achieve efficient coverage, starburst amacrine cell dendrites exhibit self-avoidance, meaning that molecular cues prevent dendrites from the same cell from crossing (Fig. 1A). Several molecular regulators of self-avoidance, such as Sema6a (Sun et al. 2013), γ-protocadherins (Lefebvre et al. 2012), and DSCAM (Fuerst et al. 2008, 2009), have been identified in starburst amacrines and other amacrine cell types. Loss of γ-protocadherins, leading to excessive self-crossing of the dendrites, has also been shown to result in impairment of cellular function, including persistence of inhibitory synaptic connections between neighboring starburst amacrine cells and excessive autapses (Kostadinov and Sanes 2015).

Fig. 1.

Dendritic morphology and function are interrelated at the cellular level. A: starburst amacrine cell dendrites efficiently fill an approximately circular area (orange), demonstrating a high degree of self-repulsion. Branches rarely extend beyond the concentration of dendritic material. B: individual dendritic branches of starburst amacrine cells show highly compartmentalized functions (represented as gray, magenta, yellow, and cyan highlights); that is, each branch serves as a computational unit. Function is regionally distributed in the arbor. C: basilar arbors of pyramidal neurons somewhat efficiently tile a given domain (pink), showing significant self-repulsion but less than that observed in starburst amacrine cells. A minority of branches stray away from the center of each arbor (yellow) in unpredictable directions. D: pyramidal neuron arbors are functionally compartmentalized with distal basilar segments and oblique apical branches (not shown) serving as distinct functional units. Functional inputs (magenta, yellow, and cyan highlights) are clustered on both basilar and apical (not shown) branches. E: crustacean stomatogastric ganglion (STG) neurons show dense arborization of a given area (orange) with no evidence of self-repulsion and send dendrites to distal locations (yellow). F: despite complex morphology, the STG neuron is electrotonically compact with little evidence of compartmentalization (blue highlight).

Similarly, the basilar arbors of cortical pyramidal neurons exhibit self-avoidance and tend to fill a defined area relatively evenly with dendrites (Fig. 1C) (Elston and Rosa 1997). However, basilar arbors are less strictly organized than starburst amacrine cells in terms of both self-repulsion and even coverage of space (Fig. 1C) (Elston and Rosa 1997). Because self-avoidance is most commonly studied in either the mammalian retina or Drosophila melanogaster, much less is known about the molecular mechanism of self-avoidance in the mammalian cortex. One transcription factor, Satb2, has been implicated in self-avoidance in the basilar arbors of cortical pyramidal neurons (Zhang et al. 2012). Although the original findings suggested that Satb2 functions primarily as a negative regulator of dendritic branching, in vivo knockdown revealed several additional roles for Satb2. Knockdown of Satb2 using in utero electroporation resulted in clumping of pyramidal neuron somata in all examined cortical areas, with greater severity in more posterior regions. At the scale of the individual neuron, Satb2 knockdown dendrites show extensive self-crossing and fasciculation, indicating that Satb2 normally functions to preserve self-avoidance (Zhang et al. 2012) Because self-avoidance is rarely assessed explicitly in morphological studies of the cortex, many potential molecular regulators may have already been identified as regulators of other components of dendritic arborization but without having had their role in self-avoidance explored or quantified. The rather nuanced interaction between dendritic arbor complexity, tiling of a functionally relevant space, and maintenance of self-avoidance presents an interesting question with implications for a neuron’s pool of possible synaptic partners as well as functional role in the larger circuit. In contrast to basilar arbors, the apical dendritic tree of pyramidal neurons seems to demonstrate neither robust self-repulsion nor a tendency to fill a dendritic field.

Both starburst amacrine cells and the basilar arbors of cortical neurons demonstrate morphological compactness and efficient, largely nonoverlapping coverage of a given volume of neuropil (Elston and Rosa 1997; Kolb et al. 1981; Vaney 1990). However, this is not the case for all neurons in all species. One notable exception is neurons of the stomatogastric ganglion (STG) in the crustacean Cancer borealis (Fig. 1E) (Otopalik et al. 2017b), which have been highlighted in a pair of recent papers connecting structure and function in this system. Each of the several functional classes of these large neurons has massive dendritic arbors composed of up to 1 cm of total neurite length (Otopalik et al. 2017b) that densely fill the neuropil surrounding the ganglion (Otopalik et al. 2017b). Unlike most mammalian neurons, these cells appear to exhibit no significant self-repulsion, and dendrites from the same neuron extensively overlap (Fig. 1E) (Otopalik et al. 2017b). One possible explanation for this radically different strategy may be hinted at in the extracellular milieu of these different neuron classes. Unlike mammalian dendrites that may be optimized for making spatially precise connections with presynaptic partners, STG dendritic morphology has been hypothesized to have evolved to optimally encounter and bind diffuse neuromodulatory input (Otopalik et al., 2017b). STG neurons receive a rich mixture of neuromodulators in the form of neurohormones and peptide neurotransmitters from several distinct sources, including extrasynaptic sources such as the hemolymph delivered by the pericardial organ (Marder and Bucher 2001; Skiebe 2001); an extensively interwoven dendritic tree might maximize the chance of modulators binding to their receptors located on the dendrite.

Cellular Structure and Function

Despite the existence of distinct morphological strategies, the primary function of dendrites, to receive and integrate input, is conserved. Because neuronal structure has a direct impact on current flow into and through the cell, morphological and function characteristics at the level of the individual neuron are fundamentally linked (Agmon-Snir and Segev 1993). To achieve a desired functional outcome, neurons must tune conductances and synaptic strengths to work with, or against, their arbor structure (Hay et al. 2013; Katz et al. 2009; Komendantov and Ascoli 2009; Mainen and Sejnowski 1996). Experience-dependent or disease-related morphological plasticity adds an additional layer of complexity because cells must cope with structural change (Kulkarni and Firestein 2012) by altering electrical properties, since even very small changes in morphology can radically change how dendritic excitability relates to action potential generation in the soma (Ferrante et al. 2013).

Pyramidal neuron morphology impacts how synaptic currents are received, integrated, and transmitted to the soma at the level of individual branches and branch point geometry (Branco and Häusser 2011; Ferrante et al. 2013; Katz et al. 2009; Losonczy and Magee 2006; Schaefer et al. 2003; Schiller et al. 2000). Although much of the work describing these characteristics has been conducted in hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Katz et al. 2009; Losonczy and Magee 2006), the morphological similarity to cortical pyramidal cells makes it plausible that many governing principles may be shared between the two populations. Pyramidal neurons are generally considered to have two distinct morphological compartments: apical and basilar dendritic arbors. Within these two compartments, further functional compartmentalization exists at the level of individual branches. In the apical arbor, oblique branches have been shown to act as functionally distinct compartments that influence the production of somatic spikes (Losonczy and Magee 2006). Similarly, distal basilar branches have also been shown to be capable of generating NMDA-dependent spikes that are restricted only to activated segments and produce appreciable somatic depolarization (Schiller et al. 2000). Interestingly, functional clustering of inputs has recently been shown in both apical and basilar arbors in vivo (Wilson et al. 2016), further suggesting that individual branches could have distinct functions (Wilson et al. 2016). Taken together (Fig. 1D), current data suggest that pyramidal neuron arbors demonstrate functional compartmentalization intermediate to the strict functional segregation observed in starburst amacrine cells (Fig. 1B; described in detail below) (Euler et al. 2002) and remarkable electrotonic compactness of crustacean STG cells (Fig. 1F) (Otopalik et al. 2017a, 2017b).

Work from Ferrante et al. (2013) has revealed that branch point morphology is a critical determinant of coupling of oblique apical branches to somatic action potential generation such that whether a dendritic spike will lead to a somatic spike is a function of the ratio of oblique branch diameter to that of the apical trunk. The substantial natural variation in this parameter is likely to contribute to the distinction between oblique branches that are and are not coupled to somatic spiking in pyramidal neurons (Ferrante et al. 2013). Furthermore, computational models indicate that changes in oblique diameter as small as 0.1 µm approximate the functional impact on coupling of a 50% loss in IKA, the A-type K+ conductance that has previously been shown to be important for functional compartmentalization of oblique dendrites (Ferrante et al. 2013). Despite the potentially large functional impact of changes in branch point morphology, analysis of this morphological feature is not common, and this model is not widely used to assess morphological change in disease or with changes in sensory experience.

At the level of single cells, neuronal architecture can vary hugely among species and even among structures within the same nervous system. Whereas some organizing principles, such as self-avoidance, are conserved in many structures, yet others seem to be largely ignored in certain systems. The common thread throughout these variable underlying components is a conservation of function. Despite significant structural differences, each cell type has finely tuned its morphological and intrinsic properties to integrate into its respective role. However, additional and more complicated interactions of morphology and function arise when we consider neural circuits.

HOW DOES NEURONAL STRUCTURE RELATE TO NEURONAL FUNCTION WITHIN A CIRCUIT?

Organization of the Cortex

One interesting question is the relationship between the morphology of a given cortical pyramidal neuron and its output, taken either individually or as part of a circuit. The ways in which morphological variation at the level of the dendritic arbor or spine contributes to the way in which a neuron integrates inputs and translates those inputs into spiking output or cell-autonomous changes have been explored for some time (Branco and Häusser 2011; Ferrante et al. 2013; Hay et al. 2013; Katz et al. 2009; Mainen and Sejnowski 1996; Stuart and Spruston 2015), but many outstanding questions remain. However, the presence of robust structural/functional divisions in the visual cortex has been appreciated for years at the level of whole circuits. The visual cortex of carnivore and primate species is arranged into functional “maps” that represent specific characteristics of visual stimuli (Fig. 2A, left), for example, edge orientation (Bonhoeffer and Grinvald 1991, 1993; Grinvald et al. 1986; Hubel and Wiesel 1977). These maps are overlaid such that each characteristic is represented for each position in the visual world (Fig. 2A, right) (Bartfeld and Grinvald 1992).

In the mature visual system, areas having similar tuning have extensive recurrent connections arising from L2/3 pyramidal neurons (Bosking et al. 1997; Gilbert and Wiesel 1989). Although areas of cortex sharing orientation tuning have been shown to be spontaneously coactive from very early in development, the means by which these spatially segregated areas come to be connected, such as whether each functional subset utilizes distinct molecular cues or whether slight biases in connectivity are refined over time, is as yet unknown. Interestingly, recent work has established that the tuning on inputs to an individual neuron is closely related to the area of the map in which its soma resides (Wilson et al. 2016), regardless of whether the map location is homogeneous (i.e., in the middle of a functional column) or heterogeneous (i.e., near a “pinwheel”) (Wilson et al. 2016). This suggests that rules for cell-cell connectivity exist independently of the local neighborhood of extracellular space that surrounds a given neuron, supporting the need for either targeted formation or refinement of connections. However, there is also contrasting evidence that suggests the opposite; Nauhaus et al. (2008) report that cells located in more homogeneous map locations do show sharper tuning than those in heterogeneous regions.

Similarly, the exact large-scale organization of rodent sensory cortex has recently been called into question. Evidence from mouse visual cortex exists to support two main hypotheses: like-tuned cells are scattered throughout the cortex (Fig. 2B) such that each property is represented in each retinotopic location, or local neighborhoods of like-tuned cells exist to a lesser degree than observed in carnivore and primate species (Fig. 2C). The failure to observe discernable receptive field property maps using a variety of methods supports the idea that like-tuned neurons are scattered throughout the mouse visual cortex, termed a “salt-and-pepper” organization (Fig. 2B) (Bonin et al. 2011; Ohki et al. 2005). Notably, this model still requires that all properties are represented at all retinotopic locations, suggesting some organizing principles still guide cell position or functional identity. More recently, evidence has suggested that local neighborhoods of like-tuned cells exist in rodent cortex (Fig. 2C) (Ringach et al. 2016). With the use of large-scale two-photon calcium imaging, it was discovered that pairs of neurons within 100 µm of each other showed significantly correlated intersectional tuning for spatial frequency and orientation (Ringach et al. 2016). In contrast to this relatively new understanding of macro-organization in the rodent visual cortex, functional organization is well-described in the rodent retina.

Mammalian Retina

Specialization of dendrites as computational units is perhaps best described in the direction selectivity circuit present in the mammalian retina (Fig. 1B) (Briggman et al. 2011; Euler et al. 2002; Lee and Zhou 2006). A key component of this circuit is the starburst amacrine cell. The dendritic arbor of these neurons serves as a site of both synaptic input and output such that all branches may receive synaptic input, but specialized distal branches form synapses with downstream retinal ganglion cells (RGCs; Euler et al. 2002). These distal branches, but not the soma and proximal dendrites, show direction-selective calcium transients (Euler et al. 2002) that arise from both circuit-level interactions with other starburst amacrine cells (Fig. 3A) (Lee and Zhou 2006) and cell-intrinsic properties (Gavrikov et al. 2003; Koren et al. 2017; Ozaita et al. 2004) such as the presence and distribution of cation-chloride cotransporters (Gavrikov et al. 2003) and Kv3 potassium channels (Ozaita et al. 2004). Mutual GABAergic connections from overlapping starburst amacrine cell dendrites are necessary to generate direct surround suppression, once again highlighting the importance of precise morphological relationships (Lee and Zhou 2006) (Fig. 3A). Each branch functions as a discrete computational unit, meaning that sister dendrites need not have the same preferred direction of motion and calcium transients in sister dendrites are not correlated (Euler et al. 2002; Gavrikov et al. 2003).

The manner in which direction selectivity is passed from starburst amacrine cells to direction-selective ganglion cells also includes a morphological mechanism, as revealed by a seminal paper from Briggman et al. (2011). Starburst amacrine cell dendrites specifically synapse onto downstream direction-selective ganglion cells when the preferred direction of a given starburst amacrine cell branch is in the opposite direction to that preferred by the ganglion cell (Briggman et al. 2011). Interestingly, work from Bos et al. (2016) has suggested that visual experience is required to sharpen direction tuning at the level of the direction-selective RGCs, although these processes have not yet been related to morphological change. This high degree of specificity does not rely only on proximity to ganglion cells with a specific preferred direction (Briggman et al. 2011); instead, the formation of synapses between individual tuned dendrites and downstream cells is precisely guided by an unknown mechanism. The result is that individual amacrine cell dendrites serve as highly tuned, computationally independent units (Fig. 1B).

Another notable contribution of morphology to retinal circuit function is the tiling of RGC dendritic arbors (Fig. 3B). RGCs in the rodent are incredibly diverse, with dozens of morphologically identifiable subtypes. In many cases, the somata of a given subtype show regular spacing across the retina, or a specific retinal subregion (Anishchenko et al. 2010; Kolb et al. 1981; Wässle et al. 1981). Dendrites from each cell overlap with neighbors to form a tiling meshwork of neurons of a given subtype (Fig. 3B). In contrast, each subtype is thought to be arranged with no relationship to cells of different subtypes (Fig. 3B) (Wässle et al. 1981). In this way, the RGC dendrites from many subtypes are able to receive input from preceding levels of retinal computation across the entire retina. Loss of several molecular regulators, including Brn3b (Lin et al. 2004) and DSCAM (Fuerst et al. 2008), have been shown to disrupt subtype specific tiling, but the exact visual impairments that might result have not been fully characterized.

Auditory Brain Stem in the Barn Owl

Barn owns can determine the location of stimuli with a high degree of precision using auditory cues. By calculating the difference in arrival time of a sound to each of the owls aural canals, called the interaural time difference, prey can be pinpointed in three-dimensional space (Moiseff and Konishi 1983). The owl’s physiology has adapted to this function in a variety of ways, including asymmetric placement of aural canals and specialized arrangement of the facial feathers. At the neuronal level, this computation requires neurons in the nucleus laminaris (NL) to detect differences in delay time between auditory signals received from each cochlea transmitted via the ipsilateral and contralateral nucleus magnocellularis (NM). Although other bird and reptile species have similar circuits that perform similar computation, the NL is morphologically distinct in the owl (Jhaveri and Morest 1982; Kubke et al. 2002; Smith 1981). During early embryonic development, the neurons in the NL migrate and laminate much as they do in chickens (Jhaveri and Morest 1982; Kubke et al. 2002; Smith 1981), a species that lacks the owl’s precision in sound localization, in terms of both lamination pattern and dendritic morphology (Kubke et al. 2002). However, by embryonic day 19, neurons throughout most of the owl NL had begun to spread out to occupy a larger rostral-caudal area (Kubke et al. 2002), in contrast to the dense packing and strict lamination observed in the chicken (Jhaveri and Morest 1982). Additionally, owl neurons in NL fully develop the same bi-tufted, polarized morphology that is observed in the chicken and then retract their long dendrites while also undergoing a proliferation of small, thinner branches (Kubke et al. 2002). The resulting circuit lacks the segregation of inputs from the contralateral and ipsilateral NM that is observed in the chicken NL (Kubke et al. 2002). Instead, synapses from the two nuclei magnocellularis are intermingled on the NL neurons’ radially symmetric arbors, from closer to the NL soma, and are evenly distributed throughout the nucleus (Kubke et al. 2002). Although this striking turning point in morphological development suggests a key role for dendritic structure in the enhanced function of this circuit, the authors rightly noted that this work is unable to distinguish the relationship between morphology and circuit function (Kubke et al. 2002). That is, does difference in cellular morphology lead to the adaptation in circuit function, or does the circuit-level adaptation shape the morphology (Kubke et al. 2002)?

Functional Clustering in the Cortex

Once thought to primarily act as passive cables, the presence of NMDA receptor-dependent regenerative spiking events generated locally in the dendrite is now well established (Branco and Häusser 2011; Schiller et al. 2000). Furthermore, these events have been shown to sharpen sensory tuning in two cortical circuits (Lavzin et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2013). Decreasing the frequency of dendritic bursts either by hyperpolarizing the neuron or infusing the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 resulted in decreased orientation selectivity in superficial layer neurons of the mouse primary visual cortex (Smith et al. 2013). Similarly, selectivity for direction of whisker deflection as well as response amplitude to whisker deflection decreased in L4 neurons of the mouse barrel cortex in the presence of MK-801, indicating that NMDA-dependent, regenerative events in the dendrites are required for normal selectivity (Lavzin et al. 2012). Although the requirement for NMDA receptors is apparent in these studies, it remains unclear to what extent alteration of the underlying arbor morphology might impact this phenomenon. Whereas several proteins are required for establishing and maintaining polarity in L4 stellate cells (Matsui et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2017) in barrel cortex, alterations in dendritic spikes have not been assessed in these models.

Continuing from these findings, it was since suggested in a recent paper from Wilson et al. (2016) that functional clustering of like inputs onto specific dendritic branches contributes to stimulus selectivity in the cortex. Pyramidal neurons in the ferret primary visual cortex were sparsely infected with a virus expressing GCaMP6f and calcium transients were imaged during presentation of drifting grating stimuli (Wilson et al. 2016). Interestingly, somatic orientation tuning was significantly sharper than what would be expected from a simple linear sum of spine responses (Wilson et al. 2016). Instead, the degree of somatic orientation tuning was correlated with input-output nonlinearity, indicating that supralinear dendritic responses may be involved in establishing somatic tuning (Wilson et al. 2016). Further analysis of spine responses revealed clustering of spines with tuning similar to that of the soma on individual dendritic branches (Wilson et al. 2016). Presence of these clusters was strongly correlated with strength of somatic tuning such that cells with more spines in clusters tended to be more strongly orientation tuned (Wilson et al. 2016). Branches with functional clustering were also revealed to more frequently produce “dendritic hotspots,” strong local increases in dendritic calcium, in response to visual stimulation (Wilson et al. 2016). These data further support a role for dendritic computation in sensory processing and may represent a motif in cortical function.

Our understanding of the contribution of functionally similar, clustered inputs in sensory processing was recently expanded by work in the mouse visual cortex by Iacaruso et al. (2017). This work suggests that not only do inputs with similar receptive fields tend to spatially cluster but also that higher order organization exists in terms of where within the dendritic arbor these inputs arrive. With the use of two-photon calcium imaging, it was found that most spines had receptive fields similar to that of the soma; however, those that did not tended to be located on higher order branches, especially in neurons in more superficial positions within the cortex. Furthermore, spines tended to share the same preference for visual stimulus orientation as the soma, except when they had a receptive field that was dissimilar to that of the soma; these spines were equally likely to prefer any stimulus orientation (Iacaruso et al. 2017). These data further support the idea that input location within the dendritic tree is an important part of cell and circuit function, warranting more study. Particularly interesting are emerging stories connecting region-specific spine clustering and learning in the cortex (Frank et al. 2018; Fu et al. 2012).

The work linking neuronal structure and function at the level of circuits reveals several organizing principles that should be considered as the field progresses. A prominent motif is that the spatial organization of neurons and their arbors, in terms of both absolute position in a structure and in relation to other cells, can have profound impact on their function. For example, the physical arrangement of starburst amacrine and retinal ganglion cells in the retina are critical for the output of the rodent retinal direction selectivity circuit. Similarly, the hypothesis of a diffuse, probabilistic wiring diagram of rodent sensory cortex implies that arbor position and spatial coverage are driving factors in determining each cell’s functional properties. This idea can be extended to the organization of inputs to a single cell. Clustering of inputs of shared function onto specific branches of the dendritic arbor facilitates transmission of these inputs to the soma through the combined biophysical and intrinsic characteristics of these branches. Fine-tuned positioning of inputs onto specific branches within dendritic arbors of cells with precise locations in tissues allows circuits to develop and perform computations within distributed systems.

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT DEVELOPMENT OF MORPHOLOGY AND FUNCTION IN THE NERVOUS SYSTEM?

Development of the Dendritic Arbor

Development of the dendritic arbor is well described up to the outgrowth of the initial neurites and establishment of neurite polarity. However, characterization of dendritic complexity development in pyramidal neurons of the rodent visual cortex is, for the most part, restricted to just two studies of rat neurons using Golgi staining that characterize both pre- (Miller 1981) and post-eye opening (Juraska 1982) changes in morphology. These analyses revealed that a great deal of arbor development occurs between 15 and 30 days of age (Juraska 1982; Miller 1981). During this time, the total length of the arbor, the length of individual branches, and the number of branches undergo a sharp increase that remains stable until at least postnatal day 60 (P60) (Juraska 1982) and is assumed to have reached maturity. This conclusion is supported by studies from Nedivi and colleagues (Chen et al. 2011; Chen and Nedivi 2013; Lee et al. 2006, 2008) that find very little plasticity in adult pyramidal neuron arbors, but instead find robust plasticity in the arbors of a specific subset of inhibitory interneurons in response to sensory deprivation (Lee et al. 2006, 2008). However, this work still leaves open the possibility that visual experience may influence the initial maturation of pyramidal neuron arbors in the visual cortex. Work in other vertebrate visual systems, primarily the Xenopus laevis optic tectum, strongly suggests that visual experience is required to reach typical levels of arbor complexity. In this species, light exposure leads to dendritic arbor elaboration, including the addition of more branches and an increase in growth rate (Sin et al. 2002). In contrast to mammalian systems, many molecular regulators of dendritic outgrowth and maturation have also been identified and studied in X. laevis optic tectum (Bestman and Cline 2008; Bestman et al. 2015; Chiu et al. 2008; Cline 1991; Faulkner et al. 2015; He et al. 2016; Nedivi et al. 1998; Sin et al. 2002; Thompson and Cline 2016; Truszkowski et al. 2016; Van Aelst and Cline 2004; Van Keuren-Jensen and Cline 2008; Wu and Cline 1998; Zou and Cline 1999), greatly furthering our understanding of how visual experience and morphology interact at the molecular level.

Development of Dendritic Spines

Much more is known about the development and plasticity of dendritic spines in the mammalian cortex. In the visual cortex, spines are considered to be in a high-motility regime early in development, meaning that spines form, extend, retract, and are eliminated frequently (Majewska and Sur 2003). As development progresses, spines become less motile (Majewska and Sur 2003) and tend to become wider and shorter, both indications of more mature sites of synaptic contact. In the visual cortex, spine turnover is lower than that seen in other cortical areas (Holtmaat et al. 2005). This maturation process can be delayed or stalled by altering visual experience, with some reports also showing an overall decrease in spine density, as well (Valverde 1971; Wallace and Bear 2004). Dark rearing tends to increase the proportion of spines that are filapodial in morphology (Tropea et al. 2010; Wallace and Bear 2004), an effect that can be rescued with 7 days of normal visual experience during the visual critical period in the mouse (Tropea et al. 2010). Spines sampled from mice that had been reared in the dark starting before eye opening until P28 show increased spine motility compared with animals that have had normal visual experience (Majewska and Sur 2003). Interestingly, increased motility is also seen after brief monocular deprivation during the critical period (Oray et al. 2004). This correlation between decreased spine motility and increasing sensory experience has been shown to extend across sensory modalities (Holtmaat et al. 2005) and may even apply to some types of learning (Roberts et al. 2010). For example, spine motility in song-learning areas of the zebra finch brain decreases as a young bird learns to better mimic his tutor’s song (Roberts et al. 2010).

Concurrent Circuit Development

A common theme among morphological studies to date is that notable morphological change is observed to co-occur with maturation or alteration in circuit function. In the mouse, dendritic outgrowth (Juraska 1982; Miller 1981) and spine motility changes (Majewska and Sur 2003; Oray et al. 2004; Tropea et al. 2010) have been shown to occur during the critical period for ocular dominance. During this epoch of increased plasticity from ~3 to 5 postnatal weeks, visual experience serves to develop a unified binocular representation of images from the two eyes. When visual experience is altered though depriving one eye of visual input, the cortex comes to respond preferentially to the simulation of the spared eye at the expense of responsivity to the obscured eye (Frenkel and Bear 2004; Gordon and Stryker 1996). Whereas other cortical response properties, such as selectivity for stimulus orientation, direction of motion, speed, or size, are less sensitive to visual deprivation in rodents (Rochefort et al. 2011), some of these properties undergo subtle refinement during the first weeks and months of life (Rochefort et al. 2011). Interestingly, the opening of this critical period corresponds well with the outgrowth of the arbor, occurring between P15 and P30 (Juraska 1982; Miller 1981), and spine motility decreases near the closure of the critical period (Majewska and Sur 2003). Furthermore, both of these morphological properties remain fairly stable following the closure of the critical period (Holtmaat et al. 2005; Juraska 1982), which again is conserved across species and sensory areas.

Though much of the work characterizing the co-occurrence of morphological and functional development has been performed in rodents and other vertebrates, such as X. laevis, the chance that these results may have a broader implication in our understanding of the brain is high. We know that many of the molecular regulators of this process (see below) are conserved between rodent models and humans. Although conservation of a gene is no guarantee of identical function in two species, it is likely that many of these genes serve similar functions across systems. Furthermore, the striking changes in dendritic morphology that we observe in the rodent brain are also present in humans, perhaps to an even more profound extent (Gilmore et al. 2018). By continuing to link factors such as dendritic arbor complexity and spine morphology to cellular output in rodent systems, we are better able to understand how morphological development may impact function in the human brain while avoiding significant technical challenges of that system.

ARE STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION LINKED AT THE LEVEL OF MOLECULAR MECHANISMS?

The relationship between structural and functional transitions in circuit maturity is still emerging in mammalian systems, in part due to having few tools with which to assess their relationships. Although we do know that molecular determinants of cell fate, such as the transcription factor Fezf2, coregulate neuronal structure and function (De la Rossa et al. 2013; Rouaux and Arlotta 2010), this does not address how the two characteristics mutually influence one another in all cases. One useful inroad is to study activity- and experience-regulated molecules. Proteins whose expression or function are influenced by sensory experience and can go on to impact cellular morphology and function represent an essential link between experience, morphology, and circuit output. Research over the last decade has highlighted a number of molecules originally identified as regulators of morphological development and stability that have been shown to have interesting, and sometimes unexpected, impacts on neuron and circuit function.

Cpg15

Molecules from diverse functional classes, including transcription factors (Bestman and Cline 2008), GTPases (Ghiretti et al. 2014; Sin et al. 2002; Van Aelst and Cline 2004), and immune proteins (Boulanger 2009; Datwani et al. 2009; Gilmore et al. 2004; Glynn et al. 2011; Kaneko et al. 2008; Shatz, 2009), have been shown to impact dendritic development. More recently, improvements in imaging technology have enabled researchers to visualize dendrites in vivo both in mouse sensory cortices and in X. laevis tadpole optic tectum. Work from Cline and colleagues (Bestman and Cline 2008; Bestman et al. 2015; Chiu et al. 2008; Cline 1991, 2001; Faulkner et al. 2015; Shen et al. 2009; Sin et al. 2002; Thompson and Cline 2016; Truszkowski et al. 2016; Van Aelst and Cline 2004; Van Keuren-Jensen and Cline 2008) has identified molecules from diverse functional classes that influence dendritic development within the context of visual experience, some of which have also been implicated in cortical development in mammalian systems. For example, candidate plasticity gene 15 (Cpg15), a small secreted protein, was found to be a potent regulator of dendritic complexity in the X. laevis optic tectum (Nedivi et al. 1998). Virally mediated overexpression of Cpg15 in tectal neurons leads to rapid, robust proliferation of the dendritic arbor as soon as 1 day postinfection (Nedivi et al. 1998). Later work went on to establish that Cpg15 plays a complex role in regulating dendritic complexity in mouse visual cortex: constitutive loss of Cpg15 leads increased or decreased dendritic complexity in an age-dependent manner (Fujino et al. 2011; Picard et al. 2014). Because Cpg15 expression is activity regulated at both the mRNA and protein levels, it is an attractive candidate molecule to regulate experience-dependent cortical development. Interestingly, Cpg15 knockout mice exhibit increased orientation selectivity and trend toward increased direction selectivity despite having starkly decreased visually evoked responses (Picard et al. 2014). Although the interaction of the morphological and functional roles of Cpg15 remains to be explored, molecules such as this one provide exciting inroads into understanding the ways in which altered morphology may impact circuit function.

Rem2

Another emerging candidate molecule is the small GTPase Rem2, a member of the highly conserved RGK (Rad Rem Rem2/Gem/Kir) family of small, Ras-like GTPases (Finlin et al. 2000). This small family of proteins are known regulators of the cytoskeleton as well as voltage-gated calcium channels (Finlin et al. 2005; Paradis et al. 2007). Like Cpg15, Rem2 is transcriptionally regulated by visual experience and has been shown to be an activity-dependent negative regulator of dendritic complexity in mammalian cells in vitro and of X. laevis optic tectum neurons in vivo (Ghiretti and Paradis 2011; Ghiretti et al. 2013, 2014; Moore et al. 2013). Rem2 was recently shown to regulate experience-dependent branch formation in mouse visual cortex during a specific time window near the opening of the visual critical period (our unpublished observations) as well as experience-dependent dendritic spine formation (Moore et al. 2018). Furthermore, Rem2 was shown to be a cell autonomous regulator of intrinsic excitability and a necessary molecule for late-phase ocular dominance plasticity (Moore et al. 2018). Interestingly, these changes in intrinsic excitability precede alterations in synaptic function, suggesting independent regulation of these two properties (Moore et al. 2017). This work cements Rem2 as a regulator of morphology, synaptic function, and circuit plasticity but has not yet disentangled the distinct and shared mechanisms among these functions.

Both of these example molecules, among many others, regulate morphology as well as cell and circuit function. While the exact role of morphology in these functional characteristics remains to be determined, studies such as these provide a molecular handle for future investigation. Perhaps these or other candidates can be made into effective tools for targeted alteration of neuronal morphology. The small GTPase Rac1 has already been used for this purpose (Hayashi-Takagi et al. 2015). A photoactivatable, synapse-targeted Rac1 construct was used to tag and specifically shrink dendritic spines in primary motor cortex that were active during a motor learning task while avoiding off-target effects of Rac1 overexpression (Hayashi-Takagi et al. 2015). This resulted in erasure of the learned task, even when the construct was photoactivated up to a day after the final training session (Hayashi-Takagi et al. 2015). One possible future direction for connecting neuronal structure and function is to make similar mutant constructs of known morphological regulators. In this way, a given protein’s role in regulating morphology can be isolated and functional consequences probed in a highly controlled manner.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE QUESTIONS

Our ability to test how neuronal structure and function are interrelated has greatly increased over the last decades. New technologies, such as two-photon imaging, calcium indicators, and new genetic tools, have allowed us to make significant progress in understanding the functional compartmentalization of dendritic arbors and how these computational units contribute to cellular and circuit function. Of particular note are advancements in understanding the prominent role of dendritic arbor structure in mammalian retinal function. Despite the need for more work in this area, a number of interesting principles can already be derived from our current knowledge.

Perhaps most importantly, we now appreciate that dendrites are not passive integrators of synaptic current and instead can serve as discrete computational units with active propagation of locally generated spikes. The effective transmission of these events critically relies on both the minute architectural layout of the dendritic arbor and the intrinsic membrane properties of subset of the arbor. We have also established that the distribution of synaptic inputs at the level of individual branches and the entire dendritic arbor can influence cellular output, specifically receptive field properties in visual cortex. On the larger scale of circuits and tissues, we can conclude that location-dependent and location-independent rules influence how a given cell integrates into its circuit and establishes its computational role in the network.

To make decisive, precise connections between neuronal structure and function, a multidisciplinary approach must be taken. Developing detailed, quantitative morphological techniques and applying them to cells in intact circuits will allow for greater understanding of how morphology is structured. Combining in vivo functional imaging and electrophysiological methods with new genetic tools will allow the careful manipulation of neuron structure in the absence of off-target effects. Continuing to identify and characterize novel molecular regulators of dendritic complexity, particularly those molecules regulated by activity, learning, or sensory experience, will contribute to the development of these new tools as well as to our understanding of a fundamental component of neuronal development and function. Through these combined efforts, it is possible to finally address the long-standing question of how neuronal structure may imply function.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Eye Institute Grant EY022122 (to S. E. V. Richards and S. D. Van Hooser) and by the Charles Hood Foundation (to S. E. V. Richards and S. D. Van Hooser) and the Henry J. Leir Brandeis-Israel Research Initiative (to S. E. V. Richards and S. D. Van Hooser).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.E.V.R. prepared figures; S.E.V.R. drafted manuscript; S.E.V.R. and S.D.V.H. edited and revised manuscript; S.E.V.R. and S.D.V.H. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Agmon-Snir H, Segev I. Signal delay and input synchronization in passive dendritic structures. J Neurophysiol 70: 2066–2085, 1993. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.5.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anishchenko A, Greschner M, Elstrott J, Sher A, Litke AM, Feller MB, Chichilnisky EJ. Receptive field mosaics of retinal ganglion cells are established without visual experience. J Neurophysiol 103: 1856–1864, 2010. doi: 10.1152/jn.00896.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartfeld E, Grinvald A. Relationships between orientation-preference pinwheels, cytochrome oxidase blobs, and ocular-dominance columns in primate striate cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 11905–11909, 1992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belichenko PV, Wright EE, Belichenko NP, Masliah E, Li HH, Mobley WC, Francke U. Widespread changes in dendritic and axonal morphology in Mecp2-mutant mouse models of Rett syndrome: evidence for disruption of neuronal networks. J Comp Neurol 514: 240–258, 2009. doi: 10.1002/cne.22009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestman JE, Cline HT. The RNA binding protein CPEB regulates dendrite morphogenesis and neuronal circuit assembly in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 20494–20499, 2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806296105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestman JE, Huang LC, Lee-Osbourne J, Cheung P, Cline HT. An in vivo screen to identify candidate neurogenic genes in the developing Xenopus visual system. Dev Biol 408: 269–291, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonhoeffer T, Grinvald A. Iso-orientation domains in cat visual cortex are arranged in pinwheel-like patterns. Nature 353: 429–431, 1991. doi: 10.1038/353429a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonhoeffer T, Grinvald A. The layout of iso-orientation domains in area 18 of cat visual cortex: optical imaging reveals a pinwheel-like organization. J Neurosci 13: 4157–4180, 1993. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-10-04157.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonin V, Histed MH, Yurgenson S, Reid RC. Local diversity and fine-scale organization of receptive fields in mouse visual cortex. J Neurosci 31: 18506–18521, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2974-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos R, Gainer C, Feller MB. Role for visual experience in the development of direction-selective circuits. Curr Biol 26: 1367–1375, 2016. [Erratum in Curr Biol 27: 927, 2017.] doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosking WH, Zhang Y, Schofield B, Fitzpatrick D. Orientation selectivity and the arrangement of horizontal connections in tree shrew striate cortex. J Neurosci 17: 2112–2127, 1997. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-06-02112.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger LM. Immune proteins in brain development and synaptic plasticity. Neuron 64: 93–109, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braitenberg V, Schüz A. Cortex: Statistics and Geometry of Neuronal Connectivity (2nd ed). Berlin: Springer, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bramham CR, Wells DG. Dendritic mRNA: transport, translation and function. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 776–789, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nrn2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco T, Häusser M. Synaptic integration gradients in single cortical pyramidal cell dendrites. Neuron 69: 885–892, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggman KL, Helmstaedter M, Denk W. Wiring specificity in the direction-selectivity circuit of the retina. Nature 471: 183–188, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature09818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Flanders GH, Lee WC, Lin WC, Nedivi E. Inhibitory dendrite dynamics as a general feature of the adult cortical microcircuit. J Neurosci 31: 12437–12443, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0420-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Nedivi E. Highly specific structural plasticity of inhibitory circuits in the adult neocortex. Neuroscientist 19: 384–393, 2013. doi: 10.1177/1073858413479824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu SL, Chen CM, Cline HT. Insulin receptor signaling regulates synapse number, dendritic plasticity, and circuit function in vivo. Neuron 58: 708–719, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline HT. Activity-dependent plasticity in the visual systems of frogs and fish. Trends Neurosci 14: 104–111, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline HT. Dendritic arbor development and synaptogenesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol 11: 118–126, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran JN, Hall AM, Roberson ED. The dendritic hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. Brain Res Bull 103: 18–28, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datwani A, McConnell MJ, Kanold PO, Micheva KD, Busse B, Shamloo M, Smith SJ, Shatz CJ. Classical MHCI molecules regulate retinogeniculate refinement and limit ocular dominance plasticity. Neuron 64: 463–470, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Rossa A, Bellone C, Golding B, Vitali I, Moss J, Toni N, Lüscher C, Jabaudon D. In vivo reprogramming of circuit connectivity in postmitotic neocortical neurons. Nat Neurosci 16: 193–200, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nn.3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberwine J, Miyashiro K, Kacharmina JE, Job C. Local translation of classes of mRNAs that are targeted to neuronal dendrites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 7080–7085, 2001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121146698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston GN, Rosa MG. The occipitoparietal pathway of the macaque monkey: comparison of pyramidal cell morphology in layer III of functionally related cortical visual areas. Cereb Cortex 7: 432–452, 1997. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.5.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euler T, Detwiler PB, Denk W. Directionally selective calcium signals in dendrites of starburst amacrine cells. Nature 418: 845–852, 2002. doi: 10.1038/nature00931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner RL, Wishard TJ, Thompson CK, Liu HH, Cline HT. FMRP regulates neurogenesis in vivo in Xenopus laevis tadpoles. eNeuro 2: e0055, 2015. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0055-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenoglio KA, Brunson KL, Baram TZ. Hippocampal neuroplasticity induced by early-life stress: functional and molecular aspects. Front Neuroendocrinol 27: 180–192, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante M, Migliore M, Ascoli GA. Functional impact of dendritic branch-point morphology. J Neurosci 33: 2156–2165, 2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3495-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlin BS, Mosley AL, Crump SM, Correll RN, Ozcan S, Satin J, Andres DA. Regulation of L-type Ca2+ channel activity and insulin secretion by the Rem2 GTPase. J Biol Chem 280: 41864–41871, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlin BS, Shao H, Kadono-Okuda K, Guo N, Andres DA. Rem2, a new member of the Rem/Rad/Gem/Kir family of Ras-related GTPases. Biochem J 347: 223–231, 2000. doi: 10.1042/bj3470223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank AC, Huang S, Zhou M, Gdalyahu A, Kastellakis G, Silva TK, Lu E, Wen X, Poirazi P, Trachtenberg JT, Silva AJ. Hotspots of dendritic spine turnover facilitate clustered spine addition and learning and memory. Nat Commun 9: 422, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02751-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel MY, Bear MF. How monocular deprivation shifts ocular dominance in visual cortex of young mice. Neuron 44: 917–923, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu M, Yu X, Lu J, Zuo Y. Repetitive motor learning induces coordinated formation of clustered dendritic spines in vivo. Nature 483: 92–95, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature10844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuerst PG, Bruce F, Tian M, Wei W, Elstrott J, Feller MB, Erskine L, Singer JH, Burgess RW. DSCAM and DSCAML1 function in self-avoidance in multiple cell types in the developing mouse retina. Neuron 64: 484–497, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuerst PG, Koizumi A, Masland RH, Burgess RW. Neurite arborization and mosaic spacing in the mouse retina require DSCAM. Nature 451: 470–474, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nature06514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino T, Leslie JH, Eavri R, Chen JL, Lin WC, Flanders GH, Borok E, Horvath TL, Nedivi E. CPG15 regulates synapse stability in the developing and adult brain. Genes Dev 25: 2674–2685, 2011. doi: 10.1101/gad.176172.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrikov KE, Dmitriev AV, Keyser KT, Mangel SC. Cation-chloride cotransporters mediate neural computation in the retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 16047–16052, 2003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2637041100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiretti AE, Kenny K, Marr MT II, Paradis S. CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of the GTPase Rem2 is required to restrict dendritic complexity. J Neurosci 33: 6504–6515, 2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3861-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiretti AE, Moore AR, Brenner RG, Chen LF, West AE, Lau NC, Van Hooser SD, Paradis S. Rem2 is an activity-dependent negative regulator of dendritic complexity in vivo. J Neurosci 34: 392–407, 2014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1328-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiretti AE, Paradis S. The GTPase Rem2 regulates synapse development and dendritic morphology. Dev Neurobiol 71: 374–389, 2011. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert CD, Wiesel TN. Columnar specificity of intrinsic horizontal and corticocortical connections in cat visual cortex. J Neurosci 9: 2432–2442, 1989. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-07-02432.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore JH, Fredrik Jarskog L, Vadlamudi S, Lauder JM. Prenatal infection and risk for schizophrenia: IL-1beta, IL-6, and TNFalpha inhibit cortical neuron dendrite development. Neuropsychopharmacology 29: 1221–1229, 2004. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore JH, Knickmeyer RC, Gao W. Imaging structural and functional brain development in early childhood. Nat Rev Neurosci 19: 123–137, 2018. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2018.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn MW, Elmer BM, Garay PA, Liu XB, Needleman LA, El-Sabeawy F, McAllister AK. MHCI negatively regulates synapse density during the establishment of cortical connections. Nat Neurosci 14: 442–451, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nn.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JA, Stryker MP. Experience-dependent plasticity of binocular responses in the primary visual cortex of the mouse. J Neurosci 16: 3274–3286, 1996. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03274.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinvald A, Lieke E, Frostig RD, Gilbert CD, Wiesel TN. Functional architecture of cortex revealed by optical imaging of intrinsic signals. Nature 324: 361–364, 1986. doi: 10.1038/324361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimura T, Kimura T, Miyakawa T. Morphological changes of blood vessels in the brain with Alzheimer’s disease. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol 45: 661–665, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay E, Schürmann F, Markram H, Segev I. Preserving axosomatic spiking features despite diverse dendritic morphology. J Neurophysiol 109: 2972–2981, 2013. doi: 10.1152/jn.00048.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi-Takagi A, Yagishita S, Nakamura M, Shirai F, Wu YI, Loshbaugh AL, Kuhlman B, Hahn KM, Kasai H. Labelling and optical erasure of synaptic memory traces in the motor cortex. Nature 525: 333–338, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nature15257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He HY, Shen W, Hiramoto M, Cline HT. Experience-dependent bimodal plasticity of inhibitory neurons in early development. Neuron 90: 1203–1214, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heagerty AM, Aalkjaer C, Bund SJ, Korsgaard N, Mulvany MJ. Small artery structure in hypertension. Dual processes of remodeling and growth. Hypertension 21: 391–397, 1993. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.21.4.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat AJ, Trachtenberg JT, Wilbrecht L, Shepherd GM, Zhang X, Knott GW, Svoboda K. Transient and persistent dendritic spines in the neocortex in vivo. Neuron 45: 279–291, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Ferrier lecture. Functional architecture of macaque monkey visual cortex. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 198: 1–59, 1977. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1977.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacaruso MF, Gasler IT, Hofer SB. Synaptic organization of visual space in primary visual cortex. Nature 547: 449–452, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nature23019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhaveri S, Morest DK. Neuronal architecture in nucleus magnocellularis of the chicken auditory system with observations on nucleus laminaris: a light and electron microscope study. Neuroscience 7: 809–836, 1982. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Ash RT, Baker SA, Suter B, Ferguson A, Park J, Rudy J, Torsky SP, Chao HT, Zoghbi HY, Smirnakis SM. Dendritic arborization and spine dynamics are abnormal in the mouse model of MECP2 duplication syndrome. J Neurosci 33: 19518–19533, 2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1745-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D, Magee JC, Colbert CM, Cristie BR. Active properties of neuronal dendrites. Annu Rev Neurosci 19: 165–186, 1996. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juraska JM. The development of pyramidal neurons after eye opening in the visual cortex of hooded rats: a quantitative study. J Comp Neurol 212: 208–213, 1982. doi: 10.1002/cne.902120210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko M, Stellwagen D, Malenka RC, Stryker MP. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediates one component of competitive, experience-dependent plasticity in developing visual cortex. Neuron 58: 673–680, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz Y, Menon V, Nicholson DA, Geinisman Y, Kath WL, Spruston N. Synapse distribution suggests a two-stage model of dendritic integration in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neuron 63: 171–177, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H, Nelson R, Mariani A. Amacrine cells, bipolar cells and ganglion cells of the cat retina: a Golgi study. Vision Res 21: 1081–1114, 1981. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(81)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komendantov AO, Ascoli GA. Dendritic excitability and neuronal morphology as determinants of synaptic efficacy. J Neurophysiol 101: 1847–1866, 2009. doi: 10.1152/jn.01235.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren D, Grove JCR, Wei W. Cross-compartmental modulation of dendritic signals for retinal direction selectivity. Neuron 95: 914–927.e4, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.020 28781167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostadinov D, Sanes JR. Protocadherin-dependent dendritic self-avoidance regulates neural connectivity and circuit function. eLife 4: e08964, 2015. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubke MF, Massoglia DP, Carr CE. Developmental changes underlying the formation of the specialized time coding circuits in barn owls (Tyto alba). J Neurosci 22: 7671–7679, 2002. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07671.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni VA, Firestein BL. The dendritic tree and brain disorders. Mol Cell Neurosci 50: 10–20, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvajo M, McKellar H, Arguello PA, Drew LJ, Moore H, MacDermott AB, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. A mutation in mouse Disc1 that models a schizophrenia risk allele leads to specific alterations in neuronal architecture and cognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 7076–7081, 2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802615105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavzin M, Rapoport S, Polsky A, Garion L, Schiller J. Nonlinear dendritic processing determines angular tuning of barrel cortex neurons in vivo. Nature 490: 397–401, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature11451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Zhou ZJ. The synaptic mechanism of direction selectivity in distal processes of starburst amacrine cells. Neuron 51: 787–799, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WC, Chen JL, Huang H, Leslie JH, Amitai Y, So PT, Nedivi E. A dynamic zone defines interneuron remodeling in the adult neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 19968–19973, 2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810149105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WC, Huang H, Feng G, Sanes JR, Brown EN, So PT, Nedivi E. Dynamic remodeling of dendritic arbors in GABAergic interneurons of adult visual cortex. PLoS Biol 4: e29, 2006. [Erratum in PloS Biol 4: e126, 2006.] doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre JL, Kostadinov D, Chen WV, Maniatis T, Sanes JR. Protocadherins mediate dendritic self-avoidance in the mammalian nervous system. Nature 488: 517–521, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature11305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Wang SW, Masland RH. Retinal ganglion cell type, size, and spacing can be specified independent of homotypic dendritic contacts. Neuron 43: 475–485, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liston C, Miller MM, Goldwater DS, Radley JJ, Rocher AB, Hof PR, Morrison JH, McEwen BS. Stress-induced alterations in prefrontal cortical dendritic morphology predict selective impairments in perceptual attentional set-shifting. J Neurosci 26: 7870–7874, 2006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1184-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losonczy A, Magee JC. Integrative properties of radial oblique dendrites in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neuron 50: 291–307, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil MA, Heussy JK, Dacheux RF, Raviola E, Masland RH. The shapes and numbers of amacrine cells: matching of photofilled with Golgi-stained cells in the rabbit retina and comparison with other mammalian species. J Comp Neurol 413: 305–326, 1999. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil MA, Masland RH. Extreme diversity among amacrine cells: implications for function. Neuron 20: 971–982, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80478-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainen ZF, Sejnowski TJ. Influence of dendritic structure on firing pattern in model neocortical neurons. Nature 382: 363–366, 1996. doi: 10.1038/382363a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska A, Sur M. Motility of dendritic spines in visual cortex in vivo: changes during the critical period and effects of visual deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 16024–16029, 2003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2636949100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major G, Larkum ME, Schiller J. Active properties of neocortical pyramidal neuron dendrites. Annu Rev Neurosci 36: 1–24, 2013. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Bucher D. Central pattern generators and the control of rhythmic movements. Curr Biol 11: R986–R996, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui A, Tran M, Yoshida AC, Kikuchi SS, U M, Ogawa M, Shimogori T. BTBD3 controls dendrite orientation toward active axons in mammalian neocortex. Science 342: 1114–1118, 2013. doi: 10.1126/science.1244505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Early life influences on life-long patterns of behavior and health. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 9: 149–154, 2003. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. Maturation of rat visual cortex. I. A quantitative study of Golgi-impregnated pyramidal neurons. J Neurocytol 10: 859–878, 1981. doi: 10.1007/BF01262658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moiseff A, Konishi M. Binaural characteristics of units in the owl’s brainstem auditory pathway: precursors of restricted spatial receptive fields. J Neurosci 3: 2553–2562, 1983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-12-02553.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AR, Ghiretti AE, Paradis S. A loss-of-function analysis reveals that endogenous Rem2 promotes functional glutamatergic synapse formation and restricts dendritic complexity. PLoS One 8: e74751, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AR, Richards SE, Kenny K, Royer L, Chan U, Flavahan K, Van Hooser SD, Paradis S. Rem2 stabilizes intrinsic excitability and spontaneous firing in visual circuits. Elife 8: e33092, 2018. doi: 10.7554/eLife.33092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse PH. Ocular anatomy, embryology, and teratology. JAMA 249: 2830–2831, 1983. doi: 10.1001/jama.1983.03330440066046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nalbantoglu J, Tirado-Santiago G, Lahsaïni A, Poirier J, Goncalves O, Verge G, Momoli F, Welner SA, Massicotte G, Julien JP, Shapiro ML. Impaired learning and LTP in mice expressing the carboxy terminus of the Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein. Nature 387: 500–505, 1997. doi: 10.1038/387500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauhaus I, Benucci A, Carandini M, Ringach DL. Neuronal selectivity and local map structure in visual cortex. Neuron 57: 673–679, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedivi E, Wu GY, Cline HT. Promotion of dendritic growth by CPG15, an activity-induced signaling molecule. Science 281: 1863–1866, 1998. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5384.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohki K, Chung S, Ch’ng YH, Kara P, Reid RC. Functional imaging with cellular resolution reveals precise micro-architecture in visual cortex. Nature 433: 597–603, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nature03274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oray S, Majewska A, Sur M. Dendritic spine dynamics are regulated by monocular deprivation and extracellular matrix degradation. Neuron 44: 1021–1030, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otopalik AG, Goeritz ML, Sutton AC, Brookings T, Guerini C, Marder E. Sloppy morphological tuning in identified neurons of the crustacean stomatogastric ganglion. eLife 6: e22352, 2017b. doi: 10.7554/eLife.22352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otopalik AG, Sutton AC, Banghart M, Marder E. When complex neuronal structures may not matter. eLife 6: e23508, 2017a. doi: 10.7554/eLife.23508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaita A, Petit-Jacques J, Völgyi B, Ho CS, Joho RH, Bloomfield SA, Rudy B. A unique role for Kv3 voltage-gated potassium channels in starburst amacrine cell signaling in mouse retina. J Neurosci 24: 7335–7343, 2004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1275-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis S, Harrar DB, Lin Y, Koon AC, Hauser JL, Griffith EC, Zhu L, Brass LF, Chen C, Greenberg ME. An RNAi-based approach identifies molecules required for glutamatergic and GABAergic synapse development. Neuron 53: 217–232, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard N, Leslie JH, Trowbridge SK, Subramanian J, Nedivi E, Fagiolini M. Aberrant development and plasticity of excitatory visual cortical networks in the absence of cpg15. J Neurosci 34: 3517–3522, 2014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2955-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringach DL, Mineault PJ, Tring E, Olivas ND, Garcia-Junco-Clemente P, Trachtenberg JT. Spatial clustering of tuning in mouse primary visual cortex. Nat Commun 7: 12270, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TF, Tschida KA, Klein ME, Mooney R. Rapid spine stabilization and synaptic enhancement at the onset of behavioural learning. Nature 463: 948–952, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nature08759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochefort NL, Narushima M, Grienberger C, Marandi N, Hill DN, Konnerth A. Development of direction selectivity in mouse cortical neurons. Neuron 71: 425–432, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo RD, McEwen BS. Stress and the adolescent brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1094: 202–214, 2006. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouaux C, Arlotta P. Fezf2 directs the differentiation of corticofugal neurons from striatal progenitors in vivo. Nat Neurosci 13: 1345–1347, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nn.2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai T, Hosoyamada Y. Are the precapillary sphincters and metarterioles universal components of the microcirculation? An historical review. J Physiol Sci 63: 319–331, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s12576-013-0274-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer AT, Larkum ME, Sakmann B, Roth A. Coincidence detection in pyramidal neurons is tuned by their dendritic branching pattern. J Neurophysiol 89: 3143–3154, 2003. doi: 10.1152/jn.00046.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]