Abstract

Skeletal muscle is the major site of postprandial peripheral glucose uptake, but in obesity-induced insulin-resistant states insulin-stimulated glucose disposal is markedly impaired. Despite the importance of skeletal muscle in regulating glucose homeostasis, the specific transcriptional changes associated with insulin-sensitive vs. -resistant states in muscle remain to be fully elucidated. Herein, using an RNA-seq approach we identified 20 genes differentially expressed in an insulin-resistant state in skeletal muscle, including cysteine- and glycine-rich protein 3 (Csrp3), which was highly expressed in insulin-sensitive conditions but significantly reduced in the insulin-resistant state. CSRP3 has diverse functional roles including transcriptional regulation, signal transduction, and cytoskeletal organization, but its role in glucose homeostasis has yet to be explored. Thus, we investigated the role of CSRP3 in the development of obesity-induced insulin resistance in vivo. High-fat diet-fed CSRP3 knockout (KO) mice developed impaired glucose tolerance and insulin resistance as well as increased inflammation in skeletal muscle compared with wild-type (WT) mice. CSRP3-KO mice had significantly impaired insulin signaling, decreased GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane, and enhanced levels of phospho-PKCα in muscle, which all contributed to reduced insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in muscle in HFD-fed KO mice compared with WT mice. CSRP3 is a highly inducible protein and its expression is acutely increased after fasting. After 24h fasting, glucose tolerance was significantly improved in WT mice, but this effect was blunted in CSRP3-KO mice. In summary, we identify a novel role for Csrp3 expression in skeletal muscle in the development of obesity-induced insulin resistance.

Keywords: Csrp3, inflammation, insulin sensitivity, MLP, muscle, obesity, type 2 diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Skeletal muscle is considered the primary site for insulin-stimulated glucose disposal, accounting for as much as 70–80% of an ingested glucose load (15, 19, 20, 43, 59). Therefore, disruption of insulin signaling in muscle has broad implications on systemic glucose homeostasis. Insulin resistance in skeletal muscle is considered to be one of the early defects in the development of type 2 diabetes (19). Growing evidence suggests a strong association between obesity, insulin resistance and chronic inflammation in skeletal muscle (25, 29, 48, 54, 75, 76). During the development of obesity, increased immune cell infiltration occurs in intermuscular and perimuscular adipose tissue, resulting in the development of chronic inflammation in skeletal muscle (29). In the obese state, increased number of immune cells including T cells and Cd11c+ macrophages infiltrate the skeletal muscle resulting in increased production of proinflammatory cytokines including TNFα, IL-1β, and IFNγ (21, 25, 29, 73). Obesity-induced inflammation activates downstream signaling pathways resulting in impaired insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in muscle (14, 36, 52, 63). While obesity is a key driving factor in the development of insulin resistance, the metabolic impairments are reversible with exercise and or weight loss (34, 46, 49). For example, both exercise and weight loss have been shown to reduce ectopic fat accumulation in muscle and improve insulin sensitivity (1, 34, 44, 46, 49, 61, 67).

While muscle insulin resistance is a key contributor to the etiology of type 2 diabetes, further investigation is needed to fully understand the molecular mechanisms responsible for the development of insulin resistance. Previous studies have characterized changes in the skeletal muscle transcriptome in lean and obese states in both mice (22, 27, 58) and humans (64, 71, 72, 77). However, it is particularly difficult to dissociate the genes associated with obesity from those specifically linked to insulin resistance. In this study, we have used a diet switch model where we feed high fat diet (HFD) to induce obesity and insulin resistance and then switch the diet to low fat diet (LFD) which results in improvements in insulin sensitivity (23, 35). By including a diet switch group, we were able to determine which HFD/obesity-induced gene expression changes switch back to a normal “preobese/insulin-sensitive” level. Using RNA-seq from skeletal muscle from LFD, HFD and diet switch (SWD) groups we identify genes associated with obesity-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS/STUDY DESIGN

Animals.

Twelve-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. CSRP3 knockout (CSRP3-KO) mice were on a mixed sv129/black swiss background and were a generous gift from Dr. Stephan Lange and have been previously described (37). All mice used in these experiments were bred from heterozygous parents, and offspring were used to subsequently generate cohorts of KO and WT mice. Mice were housed under an automated 12:12-h light-dark cycle (light period: 0600–1800) and given ad libitum access to water and food. All animal studies were reviewed and approved by the University of California, San Diego Institutional and Animal Care and Use Committee.

Study design.

Male mice were fed normal chow (NC) until 12 wk of age. For the diet-switch model, C57BL/6J mice were divided into three groups: LFD (low-fat diet, 10% fat; D12450B, Research Diets), HFD (60% fat; no. D12492, Research Diets), and SWD (switch diet from HFD to LFD; n = 12 per group). The LFD and HFD groups were fed ad libitum for 18 wk. The SWD group were fed HFD for 9 wk and then switched to LFD for a further 9 wk. All groups were euthanized at 30 wk of age. Age-matched CSRP3-KO or WT mice were maintained in our vivarium and fed either NC or HFD (from 10 wk of age) until euthanized at 20 wk of age.

Physiological tests.

Glucose tolerance tests (GTTs) were performed on mice after fasting for either 6 or 24 h. An intraperitoneal (ip) injection of glucose was administered (1 g/kg body wt) and blood glucose measured at 0, 10, 30, 60, and 90 min postinjection. Additional blood was collected at 0 and 10 min to measure glucose-stimulated insulin levels (Ultrasensitive Insulin Kit, ALPCO).

In vivo insulin signaling.

Mice were fasted for either 6 or 24 h before basal quadricep muscle tissues were collected under anesthesia. Insulin (1.5 U/kg in sterile saline) was injected into the inferior vena cava, and the contralateral quadriceps muscle tissue was collected 7 min postinjection. Tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for further processing of Western blot analysis or plasma membrane fractionation.

Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps.

Clamp studies were performed as previously described (41, 51). In brief, chronically cannulated, fasted (6 or 24 h, as indicated) mice were infused with d-[3H]glucose (PerkinElmer) at a constant rate of 5 μCi /h. After 90 min of tracer equilibration and basal sampling, glucose (50% dextrose; Abbott) and tracer (5 μCi/h) plus insulin (8 mU kg−1 min−1) were infused into the jugular vein. Blood samples were drawn from the tail vein at 10-min intervals. Steady-state conditions (120 ± 5 mg/dl) were confirmed by maintaining glucose infusion and plasma glucose concentration for a minimum of 20 min. Blood samples at t = −10, 0 (basal), 110, and 120 (end of experiment) min were taken to determine glucose specific activity and insulin concentration. Tracer-determined rates were quantified using the Steele equation for steady-state conditions (66). At steady state, the rate of glucose disappearance, or total GDR, is equal to the sum of the rate of endogenous glucose production (HGP) plus the exogenous (cold) glucose infusion rate (GIR). The IS-GDR is equal to the total GDR minus the basal glucose turnover rate.

Ex vivo skeletal muscle glucose uptake.

Whole muscle ex vivo glucose uptake was assessed using radiolabeled 2-deoxyglucose as previously described (62). Briefly, soleus muscle was excised from anesthetized animals and immediately incubated for 30 min in Complete Krebs-Henseleit buffer with or without insulin (0.36 nM) at 35°C. Muscles were then transferred and incubated for 20 min in the same buffer containing 2-[3H]deoxyglucose (3 mCi/ml) and [14C]mannitol (0.053 mCi/ml). Muscles were then snap-frozen until ready for processing. Samples were homogenized in lysis buffer and counted for radioactivity and/or subjected to Western blotting. Glucose uptake was standardized to the nonspecific uptake of mannitol and estimated as micromoles of glucose uptake per gram of tissue.

Glycogen measurement.

Skeletal muscle or liver glycogen content was determined using a glycogen assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell culture.

Mouse-derived C2C12 myoblast cells (CRL-1772, ATCC) were maintained in Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium (DMEM, Corning) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlas Biologics) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies). Cells were differentiated into myotubes in DMEM containing 2% FBS. For palmitate experiments, cells were differentiated for 7 days and then treated with 0.5 mM palmitate for 24 h. For knockdown experiments, cells were differentiated for 5 days and then transfected with either negative control (Med GC, Applied Biosystems) or 100 nM siCsrp3 (MSS203329, cat. no. 1320001, Applied Biosystems) using Lipofectamine 3000 for an additional 48 h in 2% FBS-containing DMEM.

In vitro glucose uptake.

C2C12 cells were differentiated for 5 days and transfected with siRNA for an additional 48 h before glucose uptake was assayed as previously described (42). Cells were washed in PBS and starved for 4 h in DMEM containing 0.25% fatty acid-free BSA. Cells were then washed in PBS and subsequently incubated for 60 min at 37°C with HEPES fortified Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer (HKRB), consisting of 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, NaH2PO4 (0.83 mM), Na2HPO4 (1.27 mM), NaHCO3 (15 mM), NaCl (120 mM), KCl (4.8 mM), calcium (1 mM), magnesium (1 mM), pH 7.35, and 0.25% fatty acid-free BSA. Cells were then stimulated with 100 nM insulin in HKRB for 30 min at 37°C, followed by a 10-min incubation of 1 mM 2-[3H]deoxyglucose at a specific activity 4 µCi/ml. Termination of glucose uptake proceeded with quick aspirations and washes with cold PBS. Cells were then lysed in 1 N NaOH, neutralized in 1 N HCl, and transferred into vials with scintillation fluid to be counted for radioactivity. Radioactive counts of each sample were then normalized to a protein concentration that was determined using a DC Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad).

Quantitative PCR.

Cells were harvested in RLT buffer, and mRNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Tissues were homogenized in TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen), and total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). For qPCR, samples were run in a 10-μl reaction (iTaq SYBR Green Supermix; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using a stepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression levels were calculated after normalization to the standard housekeeping gene Gapdh or 36b4 using the ΔΔCT method as described previously (51), and expressed as relative mRNA levels compared with control. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Histological analysis.

Quadriceps skeletal muscle from mice were dissected and fixed in formalin for 24 h. Tissues were transferred into 70% ethanol until embedded in paraffin. Samples were then deparaffinized, blocked, and stained with rat anti-mouse F4/80-biotin primary antibody (Bio-Rad, MCA497B). Sections were subsequently incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-streptavidin and counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. Images were captured using a Hamatsu NanoZoomer HT-2.0 slide scanner and analyzed using ImageJ Software. Four sections per mouse were analyzed by quantifying the total fat cell mass-to-total section area to quantify intramyocellular fat content, and quantifying the number of F4/80-positive-stained cells/total area for macrophage count.

Western blot.

Cells and tissue were homogenized using RIPA lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) containing 1% protease inhibitor, sodium orthovanadate, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and phosphatase cocktail 2 and 3 (Sigma). Additional mechanical homogenization of tissue was performed using a handheld pestle (Argos). Samples were spun at maximal speed for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected. Protein (15–30 µg) was denatured at 95–100°C in reducing agent (Bio-Rad) containing 1% β-mercaptoethanol. Samples underwent SDS-PAGE and transfer onto PVDF membrane (Millipore) before being blocked with a 5% BSA-Tris-buffered saline solution. Membranes were blotted overnight at 4°C in Signal Enhancer HIKARI (Nicalai USA) consisting of either of the following: 1:1,000 anti-CSRP3 (Abcam, cat. no. ab42504), anti-p-AKT Ser473 (Cell Signaling), anti-AKT (Cell Signaling), anti-GLUT4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-53566), anti-phospho-insulin receptor-β (p-IRβ; (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-81500), anti-IRβ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-711), anti-p-GSK3β (Cell Signaling), anti-GSK3β (Cell Signaling, 98325), or 1:200 anti-HSP90 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in 2.5% BSA-Tris-buffered saline solution.

Plasma membrane fractionation.

After in vivo insulin stimulation, we dissected quadriceps muscle and snap-froze them in liquid nitrogen and processed them to determine the quantity of GLUT4 in the membrane fraction as previously described (50). In brief, homogenates were centrifuged at 2,000 g for 10 min at 4°C in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 10 μl/ml protease inhibitor cocktail (Santa Cruz RIPA lysis buffer system). The supernatant was collected and centrifuged again at 9,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant went another round of ultracentrifgation, at 180,000 g, for 90 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in PBS with protease inhibitors, loaded onto a 10–30% (wt/wt) continuous sucrose gradient (0.5–1 mg protein per 5 ml gradient), and centrifuged at 48,000 rpm for 55 min in a Beckman Sw50.1 swinging bucket rotor at 4°C. The pellet of the sucrose gradient centrifugation was resuspended in PBS with protease inhibitors and underwent Western blot analysis using nitrocellulose membrane and 1:1,000 GLUT4 antibody (IF8) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-53566).

RNA-seq analysis.

Reads were first mapped to the mouse transcriptome using the Bowtie2 algorithm (38) and counted as reads per gene using an expectation maximization algorithm RSEM (40) and then analyzed for differential expression using the statistical algorithm DESeq (2). Significance is calculated as the q value, which is the smallest false discovery rate at which a gene is deemed differentially expressed (11). Genes that tracked with insulin sensitivity were defined as significantly differentially expressed between the lean and obese/insulin resistance state (q < 0.05 LFD vs. HFD), while also reverting back to levels associated with lean/insulin-sensitive states after the diet switch (q < 0.05 HFD vs. SWD) and (q > 0.05 SWD vs. LFD).

Statistics.

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software. Unless otherwise noted in the figure legend, GTTs were analyzed by repeated-measures two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Additionally, an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to compare two groups, and a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was used for multiple groups. Significance was considered at P < 0.05. All data are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

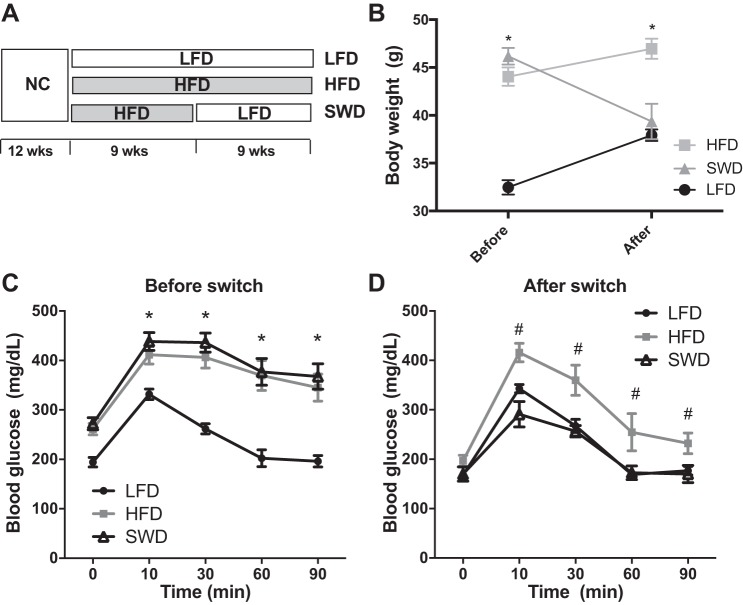

To identify genes expressed in skeletal muscle associated with insulin sensitivity and insulin resistance, we used a diet switch model in male C57BL6/J mice as previously described (23). Mice were fed a HFD for 9 wk to induce obesity (Fig. 1, A and B), glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance (Fig. 1C) and were then switched to a LFD for 9 wk to induce weight loss (Fig. 1B) and insulin sensitization in SWD mice (Fig. 1D). RNA-seq analysis of skeletal muscle from LFD, HFD, and SWD mice identified 20 transcripts of which the expression levels tracked with changes in insulin sensitivity (Table 1). For example, gene expression was differential between LFD- and HFD-fed mice and also differential between HFD and SWD. In addition, gene expression levels were comparable between LFD-fed and SWD-fed mice. Many of these genes are known to be highly expressed in muscle (i.e., myosin, tropomyosin, troponin), while others have been implicated in skeletal muscle insulin resistance in previous studies. For example, we observed decreased expression of PGC-1α in HFD-fed/insulin-resistant mice, and the expression increased after insulin sensitization induced by weight loss. This is in agreement with other studies showing decreased skeletal muscle PGC-1α expression in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with control subjects (47, 55). Conversely, increased expression of PGC-1α in skeletal muscle enhances glucose uptake by induction of Glut4 expression, resulting in improved glucose tolerance (45).

Fig. 1.

Mouse model of high-fat diet (HFD)-induced insulin resistance and low-fat diet (LFD)-induced weight loss and insulin sensitization. A: schematic diagram of diet switch model depicting the timeline of diet regimen of 3 experimental groups, LFD, HFD, and diet switch (SWD). B: body weight before and after diet switch. *P < 0.05, LFD vs. HFD in two-way ANOVA multiple comparisons. C: glucose tolerance test after 9 wk of LFD or HFD feeding but before the diet switch or (D) 9 wk after the diet switch, n = 8 per group. *Significant difference between LFD vs. HFD and LFD vs. SWD; #significant difference between HFD and SWD, determined using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test, P < 0.05.

Table 1.

Genes associated with insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle

| Entrez Gene ID | Symbol | Description | Fold (HFD/LFD) | Fold (SWD/HFD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100040970 | Rpl14-ps1 | Ribosomal protein L14, pseudogene 1 | −3.2 | 2.3 |

| 574437 | Xlr3b | X-linked lymphocyte-regulated 3B | −2.6 | 2.4 |

| 675278 | Rpl21-ps15 | Ribosomal protein L21, pseudogene 15 | −2.4 | 3.6 |

| 100040519 | Mrpl23-ps1 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L23, pseudogene 1 | −1.5 | 1.4 |

| 13009 | Csrp3 | Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 3 | −1.4 | 1.7 |

| 434233 | Gm5601 | Predicted pseudogene 5601 | −1.3 | 1.3 |

| 666904 | Gm8355 | Heat shock protein 8 pseudogene | −1.3 | 1.6 |

| 382384 | Odf3l2 | Outer dense fiber of sperm tails 3-like 2 | −1.3 | 1.4 |

| 216892 | Spns2 | Spinster homolog 2 | −1.3 | 1.5 |

| 21924 | Tnnc1 | Troponin C, cardiac/slow skeletal | −1.3 | 1.3 |

| 19017 | Ppargc1a | Peroxisome proliferative activated receptor, gamma, coactivator 1 alpha | −1.2 | 1.9 |

| 17906 | Myl2 | Myosin, light polypeptide 2, regulatory, cardiac, slow | −1.2 | 1.2 |

| 140781 | Myh7 | Myosin, heavy polypeptide 7, cardiac muscle, beta | −1.2 | 1.3 |

| 56642 | Ankrd2 | Ankyrin repeat domain 2 (stretch responsive muscle) | −1.2 | 1.5 |

| 59069 | Tpm3 | Tropomyosin 3, gamma | −1.2 | 1.3 |

| 21955 | Tnnt1 | Troponin T1, skeletal, slow | −1.2 | 1.2 |

| 78910 | Asb15 | Ankyrin repeat and SOCS box-containing 15 | 1.2 | −1.3 |

| 17684 | Cited2 | Cbp/p300-interacting transactivator, with Glu/Asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain, 2 | 1.4 | −1.3 |

| 19258 | Ptpn4 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 4 | 1.4 | −1.6 |

| 15439 | Hp | Haptoglobin | 2.1 | −1.4 |

RNA-seq analysis of low-fat diet (LFD)-, high-fat diet (HFD)-, and switch diet (SWD)-fed mice. Fold changes of genes differentially expressed between LFD and HFD mice and that reverted back to pre-obese/insulin-sensitive levels after the diet switch (SWD/HFD) are shown. In addition, these genes were expressed at comparable levels in LFD and SWD mice that were both insulin sensitive. Differential expression is defined as q < 0.05.

In these studies, we noted a significant decrease in expression of Csrp3 in HFD-fed, insulin-resistant mice compared with lean insulin-sensitive mice. Previous studies have described diverse functional roles for Csrp3, including transcriptional regulation, signal transduction, and cytoskeletal organization (5, 6, 69). Csrp3 is known to be highly inducible in skeletal muscle after exercise (8, 10, 26, 33, 74) and acutely decreased in the sedentary state (60). CSRP3-KO mice have no obvious skeletal muscle histological abnormalities, and fiber type distribution is similar in KO and WT mice (9). Due to the differential gene expression in skeletal muscle in physiological states that modulate insulin sensitivity, we investigated the role of CSRP3 in the development of obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance.

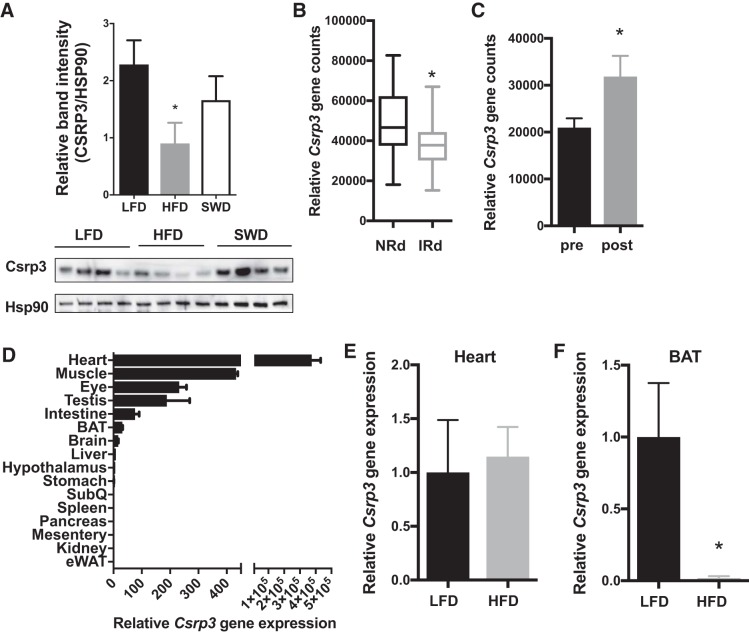

Similar to our gene expression results, CSRP3 protein expression was significantly lower in C57BL6 HFD-fed/insulin-resistant mice compared with LFD-fed mice, and the expression increased after weight loss and insulin sensitization induced by switching from HFD to LFD (Fig. 2A). We then mined microarray data from human skeletal muscle biopsies to investigate whether CSRP3 was differentially expressed between lean and obese individuals (65). We found lower CSRP3 expression in skeletal muscle from obese, insulin-resistant humans compared with lean controls (Fig. 2B; NCBI GEO data set GSE13070). We then extracted data from studies comparing expression levels in skeletal muscle from obese patients before and after weight loss induced by gastric bypass (53). CSRP3 expression was increased in skeletal muscle upon weight loss induced by bariatric surgery (Fig. 2C; NCBI GEO data set GDS2089). Csrp3 was also highly expressed in heart, and expression was also evident in BAT of WT NC-fed mice (Fig. 2D). However, HFD-induced obesity did not change levels of Csrp3 in the heart (Fig. 2E), whereas Csrp3 expression was reduced in BAT under obese conditions (Fig. 2F). Due to the high expression of Csrp3 in skeletal muscle, we hypothesized that Csrp3 might play an important role in skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity. To test this hypothesis, we studied whole body CSRP3-KO mice in both lean/insulin-sensitive and obese/insulin-resistant states (7).

Fig. 2.

Cysteine- and glycine-rich protein 3 (Csrp3) expression is decreased in insulin resistant states. A: Western blot image and quantification of Csrp3 protein expression in skeletal muscle of LFD, HFD, and SWD groups relative to heat shock protein (HSP)90 loading control. *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test. B: expression of CRSP3 in skeletal muscle biopsies from insulin-sensitive (NRd) and insulin-resistant (IRd) patients. C: skeletal muscle CSRP3 gene expression before and after weight loss induced by bariatric surgery. *P < 0.05, unpaired one-tailed Student’s t-test,. D: relative gene expression of Csrp3 in various tissues from WT mice fed normal chow (NC). Csrp3 gene expression in heart (E) and brown adipose tissue (F) LFD vs. HFD-fed mice. *P < 0.05, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

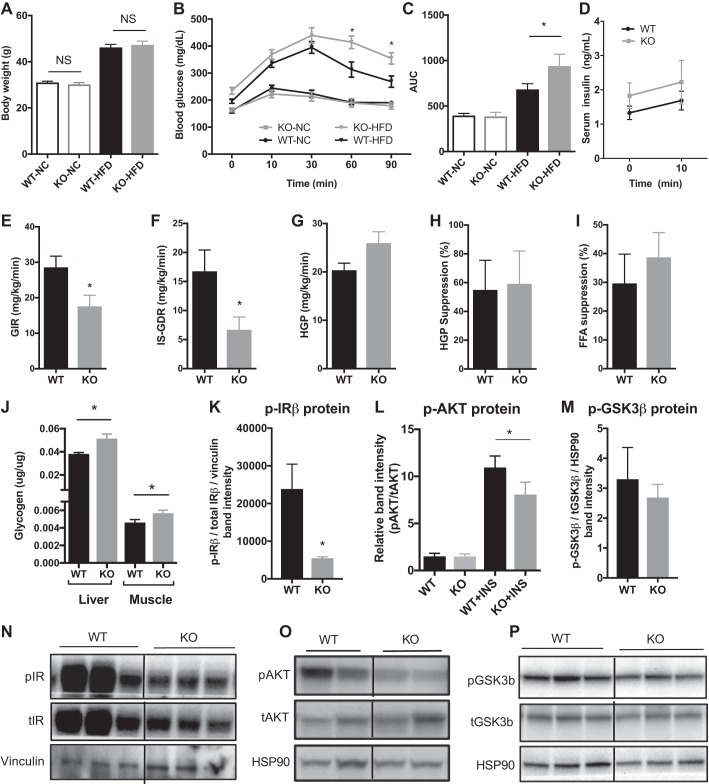

When fed the NC diet, there was no significant difference in body weight (Fig. 3A) or glucose tolerance (Fig. 3, B and C) between KO and WT mice. After HFD feeding for 8 wk, KO mice had similar body weights (Fig. 3A) but exhibited significantly impaired glucose tolerance (Fig. 3, B and C) compared with WT HFD-fed control mice. There was no observable difference in serum insulin levels upon glucose stimulation in vivo between HFD-fed WT and KO mice (Fig. 3D). To determine which insulin target tissues contribute to the systemic impairment in insulin sensitivity in KO mice, we performed hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp studies in HFD-fed mice. HFD-fed KO mice had a significantly lower GIR (Fig. 3E) and impaired insulin-stimulated glucose disposal rate (IS-GDR) compared with WT mice (Fig. 3F). No significant differences in basal HGP (Fig. 3G, P = 0.08), suppression of HGP by insulin (Fig. 3H, P = 0.7) or insulin-stimulated suppression of free fatty acids (Fig. 3I, P = 0.5) were observed, suggesting that muscle was the primary tissue contributing to the insulin-resistant phenotype of the CSRP3-KO mice. In addition, CSRP3-KO mice have elevated levels of glycogen in both the liver and muscle compared with WT, suggesting that CSRP3 depletion also affects glucose metabolism. In agreement with the impaired skeletal muscle glucose disposal in KO mice, we also observed significantly lower levels of insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of IRβ (p-IRβ; Fig. 3, K and N), AKT at Ser473 (p-AKT; Fig. 3, L and O), and a mild (nonsignificant) decrease in levels of phosphorylated GSK3β (P = 0.306; Fig. 3, M and P) in quadriceps muscle from HFD-fed KO vs. WT mice.

Fig. 3.

Effect of Csrp3 knockout (KO) on body weight, glucose tolerance, and insulin sensitivity. Body weight (A), glucose tolerance test (GTT; B), and area under the curve (AUC; C) for GTT of WT and Csrp3-KO (KO) mice fed NC or HFD for 8 wk. D: serum insulin concentration at indicated time points of GTT in HFD-fed WT and KO mice. E–I: hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp studies in HFD-fed WT and KO mice. E: glucose infusion rate (GIR); F: insulin-stimulated glucose disposal rate (IS-GDR); G: basal hepatic glucose production (HGP); H: %suppression of HGP, I: %suppression of circulating free fatty acids; J: glycogen content of liver and muscle of KO and WT mice. Insulin-stimulated phosphorylated (p-) insulin receptor-β (p-IRβ (K), p-Akt (Ser473) (L), and p-GSK3β (M) in skeletal muscle of HFD-fed WT and KO mice. N.S, not significant. B and D: *significance using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test, P < 0.05. A and C: *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Fisher’ LSD test. E–I, K, and M: *P < 0.05, unpaired two-tailed t-test. J: P < 0.05, unpaired one-tailed t-test between genotypes. L: *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test.

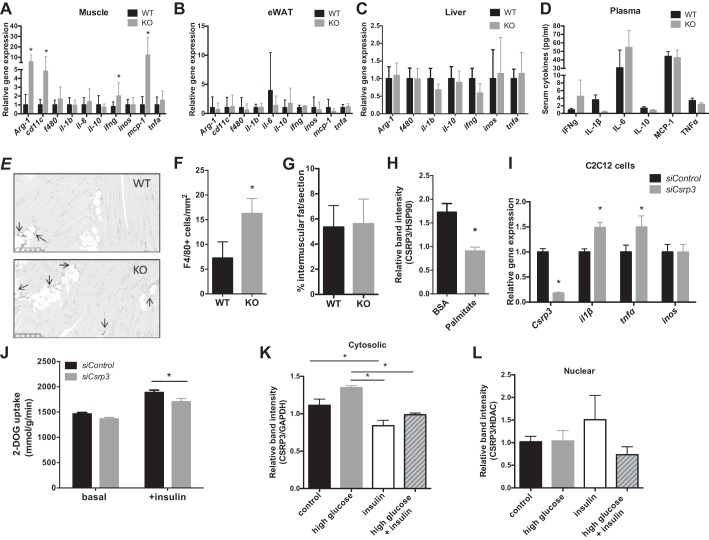

Obesity-induced inflammation plays an important role in the development of insulin resistance (52). To elucidate whether Csrp3 influences the development of obesity-induced inflammation, we compared inflammatory gene expression between KO and WT mice. We observed elevated proinflammatory gene expression including interferon-gamma (Ifng), macrophage chemoattractant protein-1 (Mcp-1), and the macrophage marker Cd11c (Fig. 4A) specifically in skeletal muscle from KO mice compared with WT HFD-fed mice, but no significant changes in inflammatory gene expression in epididymal white adipose (Fig. 4B) or liver tissues (Fig. 4C) were noted. Circulating levels of proinflammatory markers were comparable between HFD-fed WT and KO mice (Fig. 4D). Increased numbers of F4/80+ macrophages in skeletal muscle were observed by immunohistochemistry in KO skeletal muscle (Fig. 4, E and F), while there was no difference in intramyocellular fat deposition within the skeletal muscle of KO compared with WT HFD-fed mice (Fig. 4G).

Fig. 4.

CSRP3 knockout/knockdown leads to increased inflammation in vivo and in vitro. Relative gene expression of inflammatory markers in muscle (A), epididymal adipose (B), and liver tissue (C). D: levels of inflammatory markers in plasma. Representative image (E) and quantification (F) of F4/80+ immunostained cells (see arrows) of skeletal muscle sections in WT and KO HFD-fed mice, *P < 0.05, unpaired one-tailed Student’s t-test. G: average %intermuscular fat area per section of 4 captured images per mouse; n = 5. H: CSRP3 protein expression in differentiated C2C12 myotube cells after treatment with 0.5 mM palmitate for 24 h. I: gene expression of inflammatory markers after siRNA-mediated knockdown of Csrp3 in C2C12 cells. J: 2-[3H]deoxyglucose (DOG) uptake in C2C12 cells after siRNA-mediated knockdown of Csrp3. CSRP3 expression in cytosol (K) and nucleus (L) after 30-min treatment with 20 mM glucose, 100 nM insulin or both in C2C12 cells. A–I: *P < 0.05, unpaired two-tailed t-test; J: *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD post hoc test; K–L: *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test.

To further explore the role of Csrp3 in muscle inflammation, we treated C2C12 myocytes with palmitate for 24 h and observed a significant decrease in Csrp3 expression (Fig. 4H), further confirming our in vivo findings that Csrp3 expression is decreased under lipotoxic conditions. In addition, knockdown of Csrp3 expression in C2C12 myocytes resulted in increased IL-1β and TNFα gene expression (Fig. 4I) and significantly reduced insulin-stimulated glucose uptake (Fig. 4J).

Previous studies have shown that CSRP3 is shuttled to and from the nucleus in response to pharmacological or mechanical stimuli in cultured cardiac neonatal myocytes (12, 13), so we investigated its subcellular location in response to glucose and insulin in C2C12 cells. After insulin treatment, the relative abundance of cytosolic CSRP3 was decreased (Fig. 4K), and there was a trend of increased nuclear CSRP3 expression (Fig. 4L; P = 0.21 control vs. insulin), suggesting that CSRP3 moves from the cytosol to the nucleus in response to insulin stimulation.

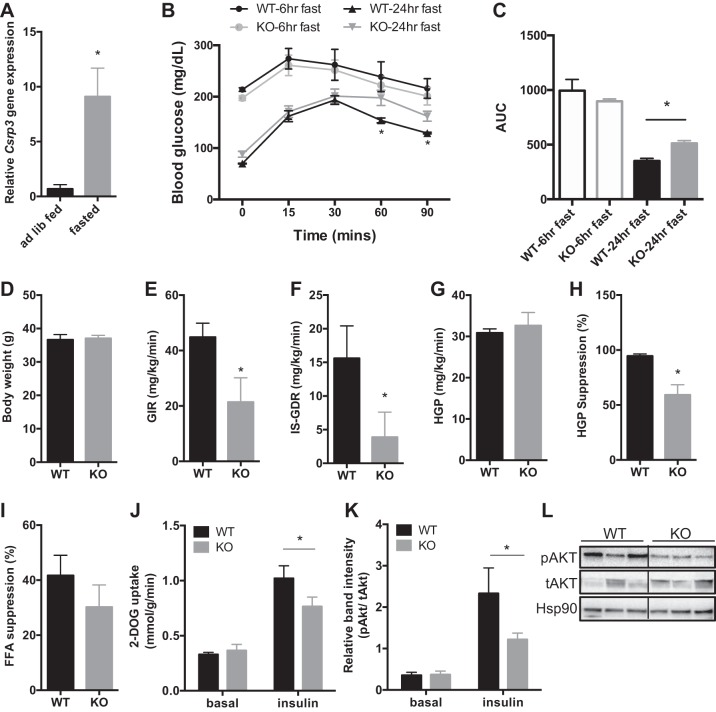

Given decreased CSRP3 expression in insulin-resistant states (Fig. 2, A–C) we tested whether Csrp3 expression was affected by fasting, which is associated with improved insulin sensitivity (3, 57). After 24 h of fasting, Csrp3 expression in skeletal muscle was increased ~10-fold compared with the fed state (Fig. 5A). Using 24-h fasting to induce Csrp3 expression, we then performed a GTT in WT and KO mice to determine whether increased Csrp3 contributed to the fasting-induced improvements in glucose tolerance. As noted previously, under ad libitum-fed conditions there was no difference in glucose tolerance in the NC-fed mice (Fig. 3B), whereas after 24-h fasting KO mice displayed impaired glucose tolerance compared with WT mice (Fig. 5, B and C). Hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic clamp studies revealed that NC-fed KO mice, when fasted for 24 h, had a significantly lower GIR (Fig. 5E) and IS-GDR compared with WT mice (Fig. 5F). While there were no differences in basal HGP or insulin-stimulated suppression of free fatty acids (Fig. 5I), KO mice had significantly lower suppression of HGP by insulin (Fig. 5H). These data suggest that the impairment in systemic insulin sensitivity in 24-h-fasted KO mice is attributable to impaired insulin action in both muscle and liver. Furthermore, KO mice displayed impaired insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle ex vivo (Fig. 5J) and impaired insulin signaling, including reduced phosphorylation of AKT (Fig. 5, K and L).

Fig. 5.

Physiological increase in skeletal muscle Csrp3 expression contributes to fasting-induced improvements in glucose tolerance. A: Csrp3 expression in ad libitum-fed or 24-h-fasted WT mice. GTT (B) and AUC (C) in lean WT and KO mice after 6- or 24-h fasting, as indicated. D: body weight was measured in NC-fed mice that underwent 24-h-fasted (E–I) hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp studies. E: GIR. F: IS-GDR. G: basal HGP. H: %suppression of HGP. I: %suppression of circulating free fatty acids. J: ex vivo 2-DOG uptake in muscle of WT and KO mice in basal and insulin-stimulated states. K and L: phosphorylation of Akt in skeletal muscle from 24-h-fasted WT and KO mice in basal and insulin-stimulated states. A, C–I: *P < 0.05 using unpaired one-tailed Student’s t-test. B: *significance using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test, P < 0.05. J and K: *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD post hoc test.

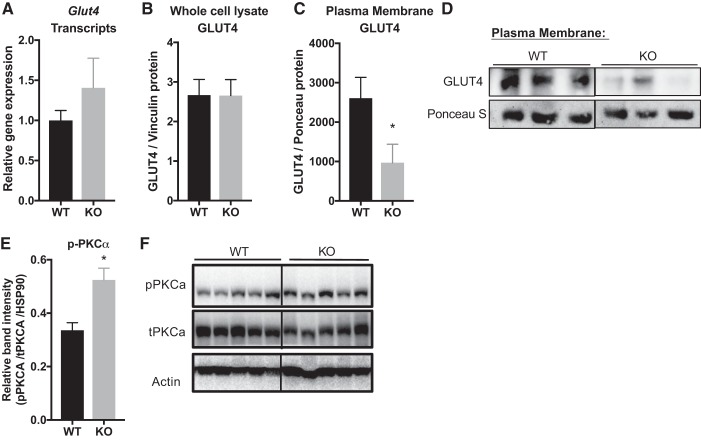

Due to the reduced insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and impairments in the insulin signaling pathway in KO vs. WT mice, we then investigated GLUT4 levels. Under HFD-fed conditions, there was no difference in Glut4 gene transcription (Fig. 6A) or total protein expression in whole cell lysates of quadriceps muscle (Fig. 6B) compared with WT control. However, upon insulin stimulation GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane was reduced in KO mice compared with HFD-fed WT controls (Fig. 6, C and D).

Fig. 6.

CSRP3 ablation in HFD-fed mice results in reduction of GLUT4 translocation and enhanced PKCα activation in skeletal muscle. GLUT4 gene expression (A) and total protein levels in whole cell lysates (B) were measured in WT vs. KO mice under basal conditions. C and D: differential centrifugation was performed to measure GLUT4 protein in plasma membrane fraction via Western blot analysis in WT and KO mice after insulin stimulation. *P < 0.05, unpaired one-tailed Student’s t-test. E and F: p-PKCα expression was measured in quadriceps muscle from WT vs. KO in basal state. *Significance at P < 0.05, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

To gain further mechanistic insights into the pathways involved in CSRP3-mediated effects on glucose regulation, we also measured protein kinase Cα (PKCα) levels in muscle from HFD-fed KO and WT mice. Previous studies have shown that CSRP3 is highly expressed in cardiac muscle (30, 31, 37, 56, 70), where it directly inhibits PKCα (37). PKC overexpression inhibits insulin signaling (16, 17, 28), whereas PKCα ablation enhances it (39). Therefore, it is possible that obesity-associated reduction of CSRP3 in skeletal muscle may result in increased PKCα expression driving insulin resistance. Western blot analysis of p-PKCα revealed increased levels in HFD-fed KO mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 6, E and F).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we applied a transcriptomic approach to identify genes that are differentially expressed in insulin-sensitive and insulin-resistant skeletal muscle. Csrp3 gene expression was significantly decreased in skeletal muscle from insulin-resistant mice and humans. We identify a novel role for CSRP3 in glucose homeostasis, obesity-induced inflammation, and insulin resistance. KO mice fed HFD developed impaired glucose tolerance and systemic insulin sensitivity compared with WT controls. KO mice also displayed impaired insulin-stimulated glucose disposal specifically in skeletal muscle associated with decreased levels of p-IRβ and p-AKT compared with WT HFD-fed mice. We measured GLUT4 levels in the plasma membrane after insulin stimulation and found that KO mice had decreased levels of membrane-bound GLUT4, which contributed to the reduced glucose uptake observed in muscle from KO vs. WT mice. CSRP3 has previously been shown to play a role in actin polymerization by cross-linking actin filaments, which protects them from depolymerization (24). Actin polymerization is required for GLUT4 translocation to the sarcolemma during insulin-stimulated glucose uptake (68). Our findings show that GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane was significantly reduced in CSRP3-KO mice. Therefore, it is possible that CSRP3-KO mice may be more vulnerable to depolymerization which could contribute to impaired glucose uptake.

Previous studies have also shown that CSRP3 is highly expressed in cardiac muscle (30, 31, 37, 56, 70), where it directly inhibits PKCα (37). Given that insulin signaling is inhibited by PKC overexpression (16, 17, 28) and enhanced by PKCα ablation (39), we hypothesized that obesity-associated reduction of Csrp3 expression in skeletal muscle may result in increased PKCα expression, driving insulin resistance. Consistent with this, we found higher levels of p-PKCα in skeletal muscle of KO mice compared with WT mice, suggesting that reduced levels of Csrp3 are associated with increased PKCα activation, which contributes to impairments in insulin sensitivity.

We found higher levels of inflammation and infiltrating F4/80+ macrophages in skeletal muscle from HFD-fed CSRP3-KO mice compared with HFD-fed WT mice. The Csrp3 gene encodes muscle LIM protein (MLP) and is part of the LIM domain-containing protein family with diverse functional roles (5, 6, 69). Notably, CSRP3 is found in both the cytoplasm and in the nucleus (6), where it interacts with transcription factors such as myoblast determination protein-1 (MyoD), myogenin, and myogenic regulatory factor 4 to promote muscle regeneration and differentiation (32). We found that acute insulin stimulation of muscle cells resulted in a significant decrease in the cytosolic pool of CSRP3 and a trend in increased expression in the nucleus. This suggests that CSRP3 localization is responsive to acute metabolic signals and supports the idea that CSRP3 plays an important transcriptional co-activator role. Therefore, it is possible that CSRP3 may regulate inflammation via nuclear shuttling of proinflammatory transcription factors, such as NF-κB, however, further studies are needed to investigate this hypothesis.

Importantly, skeletal muscle is considered the primary site for insulin-stimulated glucose disposal, accounting for as much as 70–80% of an ingested glucose load (15, 19, 20, 43, 59). Therefore, even small changes in glucose uptake in muscle have broad implications on systemic glucose homeostasis. For example, CSRP3 ablation resulted in an ~25% reduction in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in soleus muscle from fasted mice compared with WT. BAT is also an important site of glucose uptake (50), and our studies indicate that Csrp3 expression in BAT is also reduced in HFD-induced obese mice compared with lean controls. Therefore, further studies are needed to explore the role of Csrp3 expression in BAT and its contribution to glucose uptake and systemic insulin sensitivity.

CSRP3 is a highly inducible protein and is upregulated in skeletal muscle during fasting (18). We used a fasting paradigm to induce Csrp3 expression within physiologically relevant ranges and show that Csrp3 expression contributes to the improvement in glucose tolerance observed after fasting. Similar to our observations in HFD-fed CSRP3-KO mice, 24-h-fasted KO mice exhibit decreased insulin sensitivity and impaired insulin signaling, as noted by decreased insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, and lower levels of p-Akt (Ser473).

In summary, we describe a novel role of CSRP3 in the development of obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Future studies are needed to further investigate the mechanisms by which CSRP3 expression affects glucose homeostasis. Skeletal muscle is the major site for glucose disposal, which is impaired in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Therefore, understanding the underlying molecular mechanisms that contribute to the development of obesity-induced skeletal muscle insulin resistance are important to develop therapeutic strategies for the treatment of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

GRANTS

This study was supported by a pilot grant from the San Diego Skeletal Muscle Research Centre (SDSMRC) P30 AR-061303-02 (O. Osborn) and the UC San Diego/UCLA National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Diabetes Research Center P30 DK-063491 (O. Osborn). A. Hernandez-Carretero is an Institutional Research and Academic Career Development Award (IRACDA) Postdoctoral fellow, and N. T. Doan was an IRACDA Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship fellow, both supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences/National Institutes of Health Award K12 GM-068524.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.H.-C. and O.O. conceived and designed research; A.H.-C., N.W., S.A.L., V.P., N.Y.T.D., S.S., and O.O. performed experiments; A.H.-C., N.W., S.A.L., N.Y.T.D., S.S., and O.O. analyzed data; A.H.-C. and O.O. interpreted results of experiments; A.H.-C. and O.O. prepared figures; A.H.-C. and O.O. drafted manuscript; A.H.-C., S.S., and O.O. edited and revised manuscript; A.H.-C., N.W., S.A.L., and O.O. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albers PH, Bojsen-Møller KN, Dirksen C, Serup AK, Kristensen DE, Frystyk J, Clausen TR, Kiens B, Richter EA, Madsbad S, Wojtaszewski JF. Enhanced insulin signaling in human skeletal muscle and adipose tissue following gastric bypass surgery. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 309: R510–R524, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00228.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 11: R106, 2010. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anson RM, Guo Z, de Cabo R, Iyun T, Rios M, Hagepanos A, Ingram DK, Lane MA, Mattson MP. Intermittent fasting dissociates beneficial effects of dietary restriction on glucose metabolism and neuronal resistance to injury from calorie intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 6216–6220, 2003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1035720100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arber S, Caroni P. Specificity of single LIM motifs in targeting and LIM/LIM interactions in situ. Genes Dev 10: 289–300, 1996. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arber S, Halder G, Caroni P. Muscle LIM protein, a novel essential regulator of myogenesis, promotes myogenic differentiation. Cell 79: 221–231, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arber S, Hunter JJ, Ross J Jr, Hongo M, Sansig G, Borg J, Perriard JC, Chien KR, Caroni P. MLP-deficient mice exhibit a disruption of cardiac cytoarchitectural organization, dilated cardiomyopathy, and heart failure. Cell 88: 393–403, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81878-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barash IA, Bang ML, Mathew L, Greaser ML, Chen J, Lieber RL. Structural and regulatory roles of muscle ankyrin repeat protein family in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C218–C227, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00055.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barash IA, Mathew L, Lahey M, Greaser ML, Lieber RL. Muscle LIM protein plays both structural and functional roles in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 289: C1312–C1320, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00117.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barash IA, Mathew L, Ryan AF, Chen J, Lieber RL. Rapid muscle-specific gene expression changes after a single bout of eccentric contractions in the mouse. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C355–C364, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00211.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benjamini Y, Heller R. Controlling the false discovery rate—a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met 57: 289–300, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boateng SY, Belin RJ, Geenen DL, Margulies KB, Martin JL, Hoshijima M, de Tombe PP, Russell B. Cardiac dysfunction and heart failure are associated with abnormalities in the subcellular distribution and amounts of oligomeric muscle LIM protein. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H259–H269, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00766.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boateng SY, Senyo SE, Qi L, Goldspink PH, Russell B. Myocyte remodeling in response to hypertrophic stimuli requires nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of muscle LIM protein. J Mol Cell Cardiol 47: 426–435, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boon MR, Bakker LE, Haks MC, Quinten E, Schaart G, Van Beek L, Wang Y, Van Schinkel L, Van Harmelen V, Meinders AE, Ottenhoff TH, Van Dijk KW, Guigas B, Jazet IM, Rensen PC. Short-term high-fat diet increases macrophage markers in skeletal muscle accompanied by impaired insulin signalling in healthy male subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 128: 143–151, 2015. doi: 10.1042/CS20140179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouzakri K, Koistinen HA, Zierath JR. Molecular mechanisms of skeletal muscle insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rev 1: 167–174, 2005. doi: 10.2174/1573399054022785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chin JE, Dickens M, Tavare JM, Roth RA. Overexpression of protein kinase C isoenzymes alpha, beta I, gamma, and epsilon in cells overexpressing the insulin receptor. Effects on receptor phosphorylation and signaling. J Biol Chem 268: 6338–6347, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chin JE, Liu F, Roth RA. Activation of protein kinase C alpha inhibits insulin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1. Mol Endocrinol 8: 51–58, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Lange P, Ragni M, Silvestri E, Moreno M, Schiavo L, Lombardi A, Farina P, Feola A, Goglia F, Lanni A. Combined cDNA array/RT-PCR analysis of gene expression profile in rat gastrocnemius muscle: relation to its adaptive function in energy metabolism during fasting. FASEB J 18: 350–352, 2004. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0342fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 32, Suppl 2: S157–S163, 2009. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrannini E, Simonson DC, Katz LD, Reichard G Jr, Bevilacqua S, Barrett EJ, Olsson M, DeFronzo RA. The disposal of an oral glucose load in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Metabolism 37: 79–85, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(88)90033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fink LN, Oberbach A, Costford SR, Chan KL, Sams A, Blüher M, Klip A. Expression of anti-inflammatory macrophage genes within skeletal muscle correlates with insulin sensitivity in human obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 56: 1623–1628, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2897-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu L, Liu X, Niu Y, Yuan H, Zhang N, Lavi E. Effects of high-fat diet and regular aerobic exercise on global gene expression in skeletal muscle of C57BL/6 mice. Metabolism 61: 146–152, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernandez-Carretero A, Weber N, La Frano MR, Ying W, Rodriguez JL, Sears DD, Wallenius V, Borgeson E, Newman JW, Osborn O. Obesity-induced changes in lipid mediators persist after weight loss. Int J Obes (Lond) 42: 728–736, 2018. 10.1038/ijo.2017.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffmann C, Moreau F, Moes M, Luthold C, Dieterle M, Goretti E, Neumann K, Steinmetz A, Thomas C. Human muscle LIM protein dimerizes along the actin cytoskeleton and cross-links actin filaments. Mol Cell Biol 34: 3053–3065, 2014. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00651-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong EG, Ko HJ, Cho YR, Kim HJ, Ma Z, Yu TY, Friedline RH, Kurt-Jones E, Finberg R, Fischer MA, Granger EL, Norbury CC, Hauschka SD, Philbrick WM, Lee CG, Elias JA, Kim JK. Interleukin-10 prevents diet-induced insulin resistance by attenuating macrophage and cytokine response in skeletal muscle. Diabetes 58: 2525–2535, 2009. doi: 10.2337/db08-1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen JH, Conley LN, Hedegaard J, Nielsen M, Young JF, Oksbjerg N, Hornshøj H, Bendixen C, Thomsen B. Gene expression profiling of porcine skeletal muscle in the early recovery phase following acute physical activity. Exp Physiol 97: 833–848, 2012. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.063727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keller P, Vollaard NB, Gustafsson T, Gallagher IJ, Sundberg CJ, Rankinen T, Britton SL, Bouchard C, Koch LG, Timmons JA. A transcriptional map of the impact of endurance exercise training on skeletal muscle phenotype. J Appl Physiol (1985) 110: 46–59, 2011. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00634.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kellerer M, Mushack J, Seffer E, Mischak H, Ullrich A, Häring HU. Protein kinase C isoforms alpha, delta and theta require insulin receptor substrate-1 to inhibit the tyrosine kinase activity of the insulin receptor in human kidney embryonic cells (HEK 293 cells). Diabetologia 41: 833–838, 1998. doi: 10.1007/s001250050995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan IM, Perrard XY, Brunner G, Lui H, Sparks LM, Smith SR, Wang X, Shi ZZ, Lewis DE, Wu H, Ballantyne CM. Intermuscular and perimuscular fat expansion in obesity correlates with skeletal muscle T cell and macrophage infiltration and insulin resistance. Int J Obes 39: 1607–1618, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knöll R, Hoshijima M, Hoffman HM, Person V, Lorenzen-Schmidt I, Bang ML, Hayashi T, Shiga N, Yasukawa H, Schaper W, McKenna W, Yokoyama M, Schork NJ, Omens JH, McCulloch AD, Kimura A, Gregorio CC, Poller W, Schaper J, Schultheiss HP, Chien KR. The cardiac mechanical stretch sensor machinery involves a Z disc complex that is defective in a subset of human dilated cardiomyopathy. Cell 111: 943–955, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knöll R, Kostin S, Klede S, Savvatis K, Klinge L, Stehle I, Gunkel S, Kötter S, Babicz K, Sohns M, Miocic S, Didié M, Knöll G, Zimmermann WH, Thelen P, Bickeböller H, Maier LS, Schaper W, Schaper J, Kraft T, Tschöpe C, Linke WA, Chien KR. A common MLP (muscle LIM protein) variant is associated with cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 106: 695–704, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kong Y, Flick MJ, Kudla AJ, Konieczny SF. Muscle LIM protein promotes myogenesis by enhancing the activity of MyoD. Mol Cell Biol 17: 4750–4760, 1997. doi: 10.1128/MCB.17.8.4750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kostek MC, Chen YW, Cuthbertson DJ, Shi R, Fedele MJ, Esser KA, Rennie MJ. Gene expression responses over 24 h to lengthening and shortening contractions in human muscle: major changes in CSRP3, MUSTN1, SIX1, and FBXO32. Physiol Genomics 31: 42–52, 2007. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00151.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krogh-Madsen R, Thyfault JP, Broholm C, Mortensen OH, Olsen RH, Mounier R, Plomgaard P, van Hall G, Booth FW, Pedersen BK. A 2-wk reduction of ambulatory activity attenuates peripheral insulin sensitivity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 108: 1034–1040, 2010. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00977.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.La Frano MR, Hernandez-Carretero A, Weber N, Borkowski K, Pedersen TL, Osborn O, Newman JW. Diet-induced obesity and weight loss alter bile acid concentrations and bile acid-sensitive gene expression in insulin target tissues of C57BL/6J mice. Nutr Res 46: 11–21, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lackey DE, Olefsky JM. Regulation of metabolism by the innate immune system. Nat Rev Endocrinol 12: 15–28, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lange S, Gehmlich K, Lun AS, Blondelle J, Hooper C, Dalton ND, Alvarez EA, Zhang X, Bang ML, Abassi YA, Dos Remedios CG, Peterson KL, Chen J, Ehler E. MLP and CARP are linked to chronic PKCα signalling in dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Commun 7: 12120, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9: 357–359, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leitges M, Plomann M, Standaert ML, Bandyopadhyay G, Sajan MP, Kanoh Y, Farese RV. Knockout of PKC alpha enhances insulin signaling through PI3K. Mol Endocrinol 16: 847–858, 2002. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.4.0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12: 323, 2011. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li P, Fan W, Xu J, Lu M, Yamamoto H, Auwerx J, Sears DD, Talukdar S, Oh D, Chen A, Bandyopadhyay G, Scadeng M, Ofrecio JM, Nalbandian S, Olefsky JM. Adipocyte NCoR knockout decreases PPARγ phosphorylation and enhances PPARγ activity and insulin sensitivity. Cell 147: 815–826, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li P, Oh DY, Bandyopadhyay G, Lagakos WS, Talukdar S, Osborn O, Johnson A, Chung H, Mayoral R, Maris M, Ofrecio JM, Taguchi S, Lu M, Olefsky JM. LTB4 promotes insulin resistance in obese mice by acting on macrophages, hepatocytes and myocytes. Nat Med 21: 239–247, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nm.3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lorenzo M, Fernández-Veledo S, Vila-Bedmar R, Garcia-Guerra L, De Alvaro C, Nieto-Vazquez I. Insulin resistance induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in myocytes and brown adipocytes. J Anim Sci 86, Suppl 14: E94–E104, 2008. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menshikova EV, Ritov VB, Dube JJ, Amati F, Stefanovic-Racic M, Toledo FGS, Coen PM, Goodpaster BH. Calorie Restriction-induced Weight Loss and Exercise Have Differential Effects on Skeletal Muscle Mitochondria Despite Similar Effects on Insulin Sensitivity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 73: 81–87, 2017. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michael LF, Wu Z, Cheatham RB, Puigserver P, Adelmant G, Lehman JJ, Kelly DP, Spiegelman BM. Restoration of insulin-sensitive glucose transporter (GLUT4) gene expression in muscle cells by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 3820–3825, 2001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061035098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA 289: 76–79, 2003. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J, Puigserver P, Carlsson E, Ridderstråle M, Laurila E, Houstis N, Daly MJ, Patterson N, Mesirov JP, Golub TR, Tamayo P, Spiegelman B, Lander ES, Hirschhorn JN, Altshuler D, Groop LC. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet 34: 267–273, 2003. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nguyen MT, Favelyukis S, Nguyen AK, Reichart D, Scott PA, Jenn A, Liu-Bryan R, Glass CK, Neels JG, Olefsky JM. A subpopulation of macrophages infiltrates hypertrophic adipose tissue and is activated by free fatty acids via Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 and JNK-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem 282: 35279–35292, 2007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olsen RH, Krogh-Madsen R, Thomsen C, Booth FW, Pedersen BK. Metabolic responses to reduced daily steps in healthy nonexercising men. JAMA 299: 1261–1263, 2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Orava J, Nuutila P, Lidell ME, Oikonen V, Noponen T, Viljanen T, Scheinin M, Taittonen M, Niemi T, Enerbäck S, Virtanen KA. Different metabolic responses of human brown adipose tissue to activation by cold and insulin. Cell Metab 14: 272–279, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osborn O, Oh DY, McNelis J, Sanchez-Alavez M, Talukdar S, Lu M, Li P, Thiede L, Morinaga H, Kim JJ, Heinrichsdorff J, Nalbandian S, Ofrecio JM, Scadeng M, Schenk S, Hadcock J, Bartfai T, Olefsky JM. G protein-coupled receptor 21 deletion improves insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese mice. J Clin Invest 122: 2444–2453, 2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI61953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Osborn O, Olefsky JM. The cellular and signaling networks linking the immune system and metabolism in disease. Nat Med 18: 363–374, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nm.2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park JJ, Berggren JR, Hulver MW, Houmard JA, Hoffman EP. GRB14, GPD1, and GDF8 as potential network collaborators in weight loss-induced improvements in insulin action in human skeletal muscle. Physiol Genomics 27: 114–121, 2006. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00045.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patsouris D, Cao JJ, Vial G, Bravard A, Lefai E, Durand A, Durand C, Chauvin MA, Laugerette F, Debard C, Michalski MC, Laville M, Vidal H, Rieusset J. Insulin resistance is associated with MCP1-mediated macrophage accumulation in skeletal muscle in mice and humans. PLoS One 9: e110653, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patti ME, Butte AJ, Crunkhorn S, Cusi K, Berria R, Kashyap S, Miyazaki Y, Kohane I, Costello M, Saccone R, Landaker EJ, Goldfine AB, Mun E, DeFronzo R, Finlayson J, Kahn CR, Mandarino LJ. Coordinated reduction of genes of oxidative metabolism in humans with insulin resistance and diabetes: Potential role of PGC1 and NRF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 8466–8471, 2003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1032913100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paudyal A, Dewan S, Ikie C, Whalley BJ, de Tombe PP, Boateng SY. Nuclear accumulation of myocyte muscle LIM protein is regulated by heme oxygenase 1 and correlates with cardiac function in the transition to failure. J Physiol 594: 3287–3305, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP271809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pedersen CR, Hagemann I, Bock T, Buschard K. Intermittent feeding and fasting reduces diabetes incidence in BB rats. Autoimmunity 30: 243–250, 1999. doi: 10.3109/08916939908993805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pérez-Schindler J, Kanhere A, Edwards L, Allwood JW, Dunn WB, Schenk S, Philp A. Exercise and high-fat feeding remodel transcript-metabolite interactive networks in mouse skeletal muscle. Sci Rep 7: 13485, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14081-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Pathogenesis of skeletal muscle insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 90: 11–18, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)02554-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roberts MD, Childs TE, Brown JD, Davis JW, Booth FW. Early depression of Ankrd2 and Csrp3 mRNAs in the polyribosomal and whole tissue fractions in skeletal muscle with decreased voluntary running. J Appl Physiol (1985) 112: 1291–1299, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01419.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santanasto AJ, Newman AB, Strotmeyer ES, Boudreau RM, Goodpaster BH, Glynn NW. Effects of Changes in Regional Body Composition on Physical Function in Older Adults: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J Nutr Health Aging 19: 913–921, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s12603-015-0523-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schenk S, McCurdy CE, Philp A, Chen MZ, Holliday MJ, Bandyopadhyay GK, Osborn O, Baar K, Olefsky JM. Sirt1 enhances skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity in mice during caloric restriction. J Clin Invest 121: 4281–4288, 2011. doi: 10.1172/JCI58554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schenk S, Saberi M, Olefsky JM. Insulin sensitivity: modulation by nutrients and inflammation. J Clin Invest 118: 2992–3002, 2008. doi: 10.1172/JCI34260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scott LJ, Erdos MR, Huyghe JR, Welch RP, Beck AT, Wolford BN, Chines PS, Didion JP, Narisu N, Stringham HM, Taylor DL, Jackson AU, Vadlamudi S, Bonnycastle LL, Kinnunen L, Saramies J, Sundvall J, Albanus RD, Kiseleva A, Hensley J, Crawford GE, Jiang H, Wen X, Watanabe RM, Lakka TA, Mohlke KL, Laakso M, Tuomilehto J, Koistinen HA, Boehnke M, Collins FS, Parker SC. The genetic regulatory signature of type 2 diabetes in human skeletal muscle. Nat Commun 7: 11764, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sears DD, Hsiao G, Hsiao A, Yu JG, Courtney CH, Ofrecio JM, Chapman J, Subramaniam S. Mechanisms of human insulin resistance and thiazolidinedione-mediated insulin sensitization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 18745–18750, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903032106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steele R. Influences of glucose loading and of injected insulin on hepatic glucose output. Ann N Y Acad Sci 82: 420–430, 1959. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1959.tb44923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stephenson EJ, Smiles W, Hawley JA. The relationship between exercise,nutrition and type 2 diabetes. Med Sport Sci 60: 1–10, 2014. doi: 10.1159/000357331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsakiridis T, Vranic M, Klip A. Disassembly of the actin network inhibits insulin-dependent stimulation of glucose transport and prevents recruitment of glucose transporters to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 269: 29934–29942, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vafiadaki E, Arvanitis DA, Sanoudou D. Muscle LIM Protein: Master regulator of cardiac and skeletal muscle functions. Gene 566: 1–7, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.04.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vandenbosch BJ, van den Burg CM, Schoonderwoerd K, Lindsey PJ, Scholte HR, de Coo RF, van Rooij E, Rockman HA, Doevendans PA, Smeets HJ. Regional absence of mitochondria causing energy depletion in the myocardium of muscle LIM protein knockout mice. Cardiovasc Res 65: 411–418, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Väremo L, Henriksen TI, Scheele C, Broholm C, Pedersen M, Uhlén M, Pedersen BK, Nielsen J. Type 2 diabetes and obesity induce similar transcriptional reprogramming in human myocytes. Genome Med 9: 47, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0432-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Väremo L, Scheele C, Broholm C, Mardinoglu A, Kampf C, Asplund A, Nookaew I, Uhlén M, Pedersen BK, Nielsen J. Proteome- and transcriptome-driven reconstruction of the human myocyte metabolic network and its use for identification of markers for diabetes. Cell Reports 11: 921–933, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Varma V, Yao-Borengasser A, Rasouli N, Nolen GT, Phanavanh B, Starks T, Gurley C, Simpson P, McGehee RE Jr, Kern PA, Peterson CA. Muscle inflammatory response and insulin resistance: synergistic interaction between macrophages and fatty acids leads to impaired insulin action. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E1300–E1310, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90885.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vincent B, Windelinckx A, Nielens H, Ramaekers M, Van Leemputte M, Hespel P, Thomis MA. Protective role of alpha-actinin-3 in the response to an acute eccentric exercise bout. J Appl Physiol (1985) 109: 564–573, 2010. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01007.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112: 1796–1808, 2003. doi: 10.1172/JCI200319246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu H, Ballantyne CM. Skeletal muscle inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. J Clin Invest 127: 43–54, 2017. doi: 10.1172/JCI88880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang X, Pratley RE, Tokraks S, Bogardus C, Permana PA. Microarray profiling of skeletal muscle tissues from equally obese, non-diabetic insulin-sensitive and insulin-resistant Pima Indians. Diabetologia 45: 1584–1593, 2002. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0905-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]