Abstract

The homeobox transcription factor Meis1 is required for mammalian development, and its overexpression plays a role in tumorigenesis, especially leukemia. Meis1 is known to be expressed in kidney stroma, but its function in kidney is undefined. We hypothesized that Meis1 may regulate stromal cell proliferation in kidney development and disease and tested the hypothesis using cell lineage tracing and cell-specific Meis1 deletion in development, aging, and fibrotic disease. We observed strong expression of Meis1 in platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β-positive pericytes and perivascular fibroblasts, both in adult mouse kidney and to a lesser degree in human kidney. Either bilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury or aging itself led to strong upregulation of Meis1 protein and mRNA in kidney myofibroblasts, and genetic lineage analysis confirmed that Meis1-positive cells proliferate as they differentiate into myofibroblasts after injury. Conditional deletion of Meis1 in all kidney stroma with two separate tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase drivers had no phenotype with the exception of consistent induction of the tubular injury marker kidney injury molecule-1 (Kim-1) only in Meis1 mutants. Further examination of Kim-1 expression revealed linkage disequilibrium of Kim-1 and Meis1, such that Meis1 mutants carried the longer BALB/c Kim-1 allele. Unexpectedly, we report that this Kim-1 allele is expressed at baseline in wild-type BALB/c mice, without any associated abnormalities, including long-term fibrosis, as predicted from the literature. We conclude that Meis1 is specifically expressed in stroma and myofibroblasts of mouse and human kidney, that it is not required for kidney development, disease, or aging, and that BALB/c mice unexpectedly express Kim-1 protein at baseline without other kidney abnormality.

INTRODUCTION

Several lines of inquiry have recently refocused interest in kidney stromal cells, cell types in the interstitium that have historically been less investigated than adjacent epithelia. One reason for this renewed interest is the recognition that pericytes and perivascular fibroblasts are the primary progenitor pool for myofibroblasts in fibrotic disease, so understanding the biology of this transition may lead to the identification of novel therapeutic targets (18). There is also a growing appreciation for tubular-interstitial cross talk in renal repair, maladaptive repair, fibrosis, and aging. Whereas important roles for developmental signaling pathways such as the Wnt, hedgehog, and transforming growth factor-β pathways in kidney pericyte, perivascular fibroblast, and fibroblast signaling have been described, considerably less is known concerning transcriptional regulators of kidney stroma (11).

Homeobox protein Meis1 (Meis1) is a transcription factor that belongs to the three-amino acid loop extension (TALE) family of homeobox proteins. Required for normal mammalian development (2, 15), it also plays important roles in tumorigenesis, both in solid tumors (7) and, especially, in leukemias (27, 33, 36). Meis1 was recently identified as a regulator of postnatal cardiomyocyte cell cycle arrest (29). In that study, mice with cardiomyocyte-specific Meis1 deletion had increased cardiomyocyte proliferation after injury, whereas mice with cardiac-specific Meis1 overexpression had decreased heart regeneration after infarction compared with wild-type mice. These effects were mediated by Meis1-dependent transcriptional activation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p15, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (p16INK4a), and p21. In kidney, Meis1 has been reported to be expressed in the stroma during nephrogenesis (6), and defects in kidney development have also been observed in Meis1-mutant embryos (15). Since p16INK4a is known to accumulate in aged mouse and human kidney (4, 25, 31, 32, 34) and Meis1 can induce p16INK4a, we hypothesized that Meis1 might play a role in regulating stromal proliferation during renal injury and aging.

Using reporter mice, antibodies, and genetic lineage tracing, we show that Meis1 is expressed in all kidney stromal cells in humans and mice. Injury induces proliferative expansion of these cells as they differentiate into myofibroblasts. Conditional deletion of Meis1 in kidney stroma had no effect, aside from the apparent specific induction of the tubular injury marker kidney injury molecule-1 (Kim-1), which was expressed in proximal tubule cells. The explanation for the unexpectedly normal kidney phenotype in Meis1 mutants, despite Kim-1 expression, is linkage disequilibrium between the Kim-1 and Meis1 genes, such that Meis1 mutants expressed only the BALB/c Kim-1 allele, which we now report is unexpectedly expressed in wild-type BALB/c adult mouse kidney.

METHODS

Human kidney.

Human kidney specimens were obtained under a protocol approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board. Kidney parenchyma was obtained from discarded human donor kidney with donor anonymity preserved. The injured kidney came from a 62-yr-old man with a serum creatinine of 3.3 mg/dl at time of collection. The healthy kidney was from a 38-yr-old woman with a serum creatinine of 0.6 mg/dl. The latter kidney was declined for transplantation because of a vein defect.

Animals.

All mouse experiments were performed according to the animal experimental guidelines issued by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Washington University in St. Louis. Meis1f/f;R26CreERt2 (floxed/floxed Meis1;Rosa26-Cre recombinase-estrogen receptort2) mice and Meis1CreERt2 and Meis1-eCFP (Meis1-enhanced cyan fluorescent protein) mice were kindly donated by Dr. Ashish Kumar (37) and Dr. Miguel Torres (13), respectively. Rosa26tdTomato (JAX stock no. 007909), FoxD1-GC [forkhead box D1-green fluorescent protein (GFP)-Cre, JAX stock no. 012463], BALB/c (JAX stock no. 000651), and C57BL/6J (JAX stock no. 000664) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All mouse lines used have a mixed background. Genotyping was performed as per protocols from the donating investigators and the Jackson Laboratory. Lineage tracing was performed in 8–12-wk-old male mice. Tamoxifen (10 mg) was administered via oral gavage, three doses every other day, and after a 2-wk washout period, surgery was performed.

Surgery.

In all surgical procedures, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and Buprenorphine SR was administered for pain control. Unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) was performed as follows. An incision was made in the left flank, and the ureter was tied off at the level of the lower pole with two 4-0 silk ties. Mice were euthanized 10 days after surgery. For unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury (Uni-IRI), a left flank incision was made and the left kidney was exposed. Ischemia was induced by clamping the renal pedicle with a nontraumatic microaneurysm clamp (Roboz, Rockville, MD) for 28 min. For bilateral IRI (Bi-IRI), 26 min of ischemia were used.

Tissue preparation and histology.

Mice were euthanized and subsequently perfused via the left ventricle with ice-cold PBS. Kidneys were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde on ice for 1 h, then incubated in 30% sucrose at 4°C overnight, and embedded in optimum cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetek). Kidney tissue was cryosectioned into 6-μm sections and mounted on Superfrost slides. Immunofluorescent staining was performed as previously described (10). Briefly, sections were washed with 1X PBS for 10 min, then permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X for 10 min, and subsequently blocked with 5% BSA in PBS. Primary antibodies were incubated for 1 h at room temperature, and sections were washed with 1X PBS for 5 min × 3. Secondary antibodies were used at 1:200 dilutions and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were counterstained with DAPI. Antibodies used were as follows: Meis1, vimentin, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (CD31), endomucin, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β (PDGFRβ; Abcam); Meis1/2/3 (Active Motif, for human samples); PDGFRβ and proliferation marker protein Ki-67 (Ki67; eBioscience); α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; Sigma-Aldrich); and hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 1 (HAVCR1; R&D Systems).

Real-time PCR.

Tissue was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately upon harvesting. RNA extraction was performed using the Direct-zol MiniPrep Plus kit (Zymo, Irvine, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA (600 ng) was reversed transcribed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Life Technologies). Quantitative RT-PCR was done using the iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene, and data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method, where ΔΔCt is comparative threshold cycle. Primers used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used

| Gene | Forward Primer 5′ → 3′ | Reverse Primer 5′ → 3′ |

|---|---|---|

| Meis1 | CGTGGCATCTTTCCCAAAGTA | CTGTTCTTCAGAAGGGTAAGGG |

| GAPDH | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG | TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA |

| Col1α1 | TGACTGGAAGAGCGGAGAGT | GTTCGGGCTGATGTACCAGT |

| α-SMA | CTGACAGAGGCACCACTGAA | CATCTCCAGAGTCCAGCACA |

| Fibronectin | ATGTGGACCCCTCCTGATAGT | GCCCAGTGATTTCAGCAAAGG |

| Havcr1 | AAACCAGAGATTCCCACACG | GTCGTGGGTCTTCCTGTAGC |

| NGAL | ACCACGGACTACAACCAGTTC | AAGCGGGTGAAACGTTCCTT |

| Epo | GTGGAAGAACAGGCCATAGAA | GTCTATATGAAGCTGAAGGGTCTC |

| Vegf | TCATGCGGATCAAACCTCAC | TCTGGCTTTGTTCTGTCTTTCT |

| GLUT1 | TCTGTCGGCCTCTTTGTTAATC | CCAGTTTGGAGAAGCCCATAA |

| Hif1α | CGGCGAGAACGAGAAGAAAAAG | TGGGGAAGTGGCAACTGATG |

α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; Col1α1, collagen-α1(I); Epo, erythropoietin; GLUT1, glucose transporter 1; Havcr1, hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 1; Hif1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α; Meis1, homeobox protein Meis1; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Image quantification.

Quantification of tdTomato and CD31 area was done using Fiji (National Institutes of Health) in high-power images (×400) for a total of 10 pictures. Quantification was performed as a percentage of total pixel area.

Sensitivity and specificity quantification.

Kidney sections from Meis1CreERt2;tdTom+/− mice were stained with Meis1 antibody (ab124686; Abcam), and ×400 images (n = 10) were taken randomly. A true positive (TP) cell was defined as a tdTomato cell that expresses Meis1. A false negative (FN) cell is non-tdTomato cell that expresses Meis1. A true negative (TN) is a non-tdTomato cell that does not express Meis1. A false positive (FP) is a tdTomato cell that does not express Meis1. Sensitivity is then defined as TP/(TP + FN) and specificity as TN/(FP + TN).

Glomerular filtration rate measurement.

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was measured through transcutaneous elimination kinetics of FITC-sinistrin. FITC-sinistrin (Fresenius Kabi) was used at 30 mg/ml and injected at 7.5 mg/100 mg body wt. Further details of the GFR measurement are as described by Herrera Pérez et al. (14).

Morphometric evaluation.

Body weight was measured just before euthanasia. Kidney weights were measured soon after harvesting and removal of the renal capsule. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) measurement was done using the QuantiChrom Urea Assay kit as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Glomerular count was done by counting the number of glomeruli seen in 10 random fields (×200 zoom) in kidney sections stained for α-SMA (immunofluorescence staining).

Tubular injury score.

Quantification of tubular injury was done in 10 random fields (×200 zoom) per kidney section stained with period acid-Schiff (PAS), using the following injury score: 0, 0–5%; 1, 5–10%; 2, 11–25%, 3, 26–45%, 4, 46–75%; and 5, 76–100%, for tubular atrophy, dilation, protein casts, necrotic cells, and brush border loss.

RESULTS

Meis1 is expressed in mesenchymal cells in adult kidney.

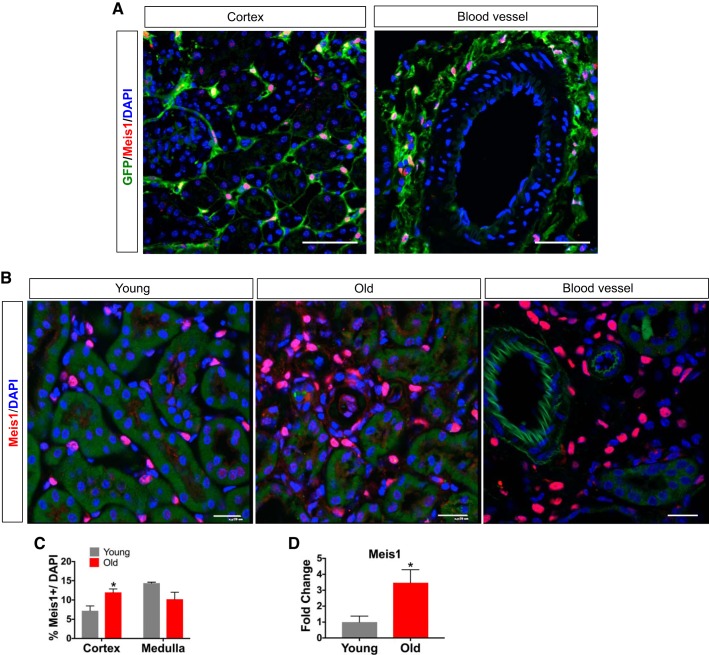

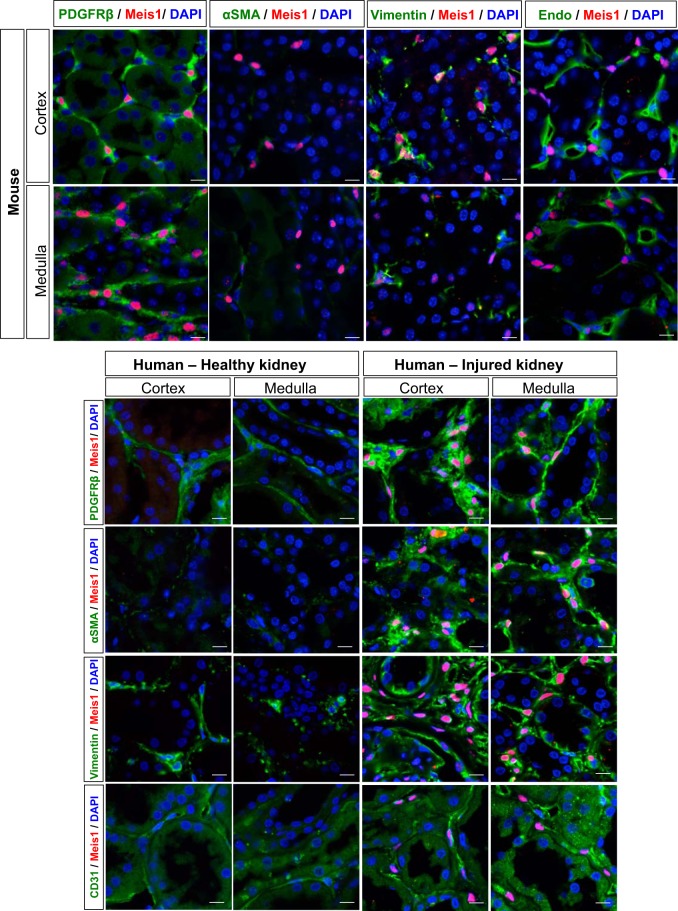

We validated the specificity of our Meis1 antibody by comparing expression of endogenous Meis1 to a Meis1-eCFP reporter line (13). In adult, uninjured kidney, there was excellent concordance between cytoplasmic eCFP expression (using an anti-GFP antibody) and nuclear Meis1 staining (Fig. 1A), without any detectable nonspecific staining. In young adult, uninjured C57BL/6 mice, Meis1 is expressed in the renal interstitium in health (Fig. 1B). In old mice (24 mo), Meis1 expression was increased compared with young mouse kidney and remained exclusively localized to the interstitium. Meis1-positive cells were also located in the perivascular niche (Fig. 1, A and B). There was increased Meis1 expression in the cortex of the aging kidney (Fig. 1C) with a slight reduction of Meis1 expression in aged medulla. Quantification of Meis1 mRNA levels confirmed increased Meis1 expression in old versus young kidney (Fig. 1D). To better define cell types expressing Meis1 and to assess MEIS1 expression in human kidney, we costained uninjured, young mouse kidney and healthy adult human kidney with a myofibroblast marker (α-SMA), stromal markers (vimentin and PDGFRβ), and endothelial cell markers (CD31 and endomucin; Fig. 2). In mouse cortex, there were very few α-SMA-positive cells, and nearly all Meis1-positive cells were α-SMA negative. In healthy human kidney, there was almost no baseline expression of MEIS1, except for a few rare interstitial cells. By contrast, when staining injured human kidney tissue, there were substantial numbers of α-SMA-positive interstitial myofibroblasts; many of these were Meis1 positive, and this was more prominent in the medullary region. We could also detect α-SMA-negative, MEIS1-positive interstitial cells in human kidney.

Fig. 1.

Homeobox protein Meis1 (Meis1) is expressed in interstitium and perivasculature of adult mouse and human kidney. A: sections from Meis1-enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (Meis1-eCFP) reporter mouse kidney (uninjured) were stained for enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) and Meis1 to validate Meis1 antibody. Note highly concordant staining of nuclei with endogenous Meis1 and of cytoplasm with eGFP. Scale bars, 50 μm. B: Meis1 expression is localized to the interstitial compartment in uninjured young and old mouse kidney. There is increased Meis1 expression in the kidney of aging mice. Also note Meis1 expression around blood vessels. Scale bars, 20 μm. C: quantification of Meis1-positive nuclei per total nuclei in young vs. old mice. There is increased Meis1 expression in the interstitial compartment in the cortex in the old mice compared with young. D: Meis1 mRNA expression is increased in the aging mouse kidney consistent with the histological expression. Here, n = 4 in each group. Data were analyzed by unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Homeobox protein Meis1 (Meis1) is specifically expressed in kidney stroma in adult mouse and human kidney. Characterization of the Meis1-positive cells in uninjured mouse and human kidney. Injured human kidney was also included for comparison. Meis1-positive cells coexpress α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β (PDGFRβ) in injured human kidney indicating that these cells are myofibroblasts. In the majority of cases, there is no coexpression of endomucin (Endo, mouse) or platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (CD31, human) indicating that these are not endothelial cells, but Meis1-positive cells are usually located adjacent to endothelium, in the pericyte niche. Zoom ×1,200; scale bars, 10 μm.

Meis1-positive cells costained for PDGFRβ in nearly all cases in both mouse (~95% coexpression) and human cortex and medulla of injured kidney. The other 5% are a combination of macrophages (<1%, data not shown) and smooth muscle cells in arterioles. Vimentin was also coexpressed in Meis1-positive cells of mouse and human kidney. Additionally, Meis1-positive cells were usually found adjacent to endomucin-positive endothelial cells in mouse cortex and medulla, and adjacent to CD31-positive endothelial cells in human kidney, suggesting a pericyte identity for at least some Meis1-positive cells. However, we did not observe Meis1 expressed in endothelial cells in either mouse or human kidney. Taken together, these results suggest that Meis1 is expressed in a subset of perivascular fibroblasts and pericytes in health and is a specific marker of myofibroblasts in aging.

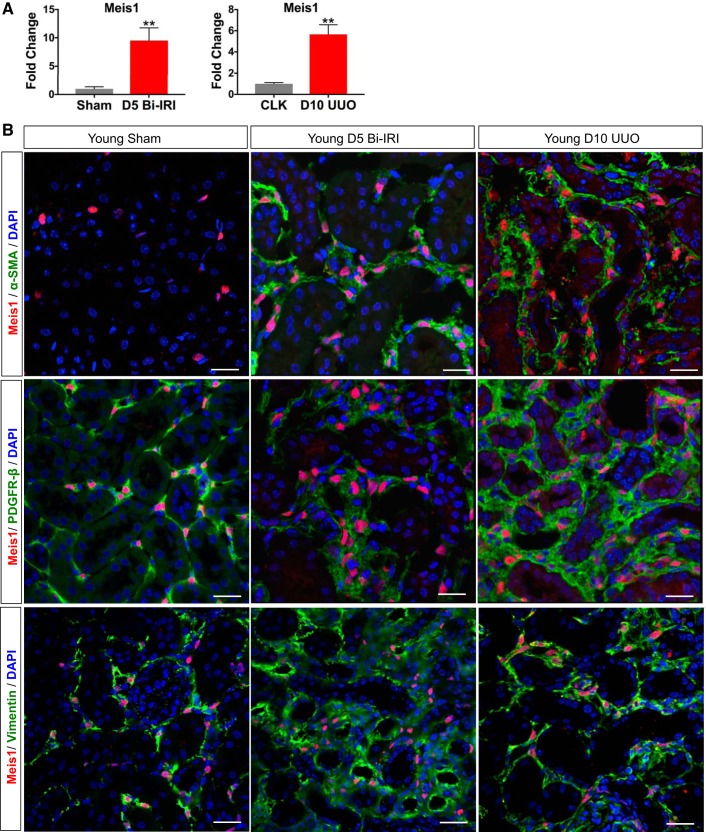

Meis1 is upregulated in both acute and chronic kidney injury.

Pericytes and perivascular fibroblasts are myofibroblast progenitors that undergo proliferative expansion in both acute and chronic kidney injury (19). Since we had localized Meis1 expression to a subset of PDGFRβ-positive stroma, we next asked whether Meis1 expression was altered in two different models of renal injury: Bi-IRI and UUO. At day 5 after Bi-IRI, a time point of early recovery, Meis1 was upregulated almost 10-fold compared with sham controls. When evaluating day 10 after UUO, when significant fibrosis is expected, Meis1 mRNA expression increased fivefold compared with the contralateral kidney (CLK; Fig. 3A). The increased Meis1 mRNA was accompanied by a clear increase in Meis1 cell number in both IRI and UUO models. Costaining with α-SMA demonstrates that Meis1 expression after injury is localized in interstitial myofibroblasts (Fig. 3B). We also observed coexpression with vimentin in both IRI and UUO (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Homeobox protein Meis1 (Meis1) is upregulated during acute and chronic kidney injury. A: upregulation of Meis1 mRNA expression in day 5 bilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury (D5 Bi-IRI) and day 10 unilateral ureteral obstruction (D10 UUO). CLK, contralateral kidney. B: immunofluorescent staining showing increased expression of Meis1-positive cells in Bi-IRI and UUO. Note that in injury, Meis1 expression colocalizes with α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), suggesting myofibroblast differentiation of Meis1 progenitors. PDGFRβ, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β. Scale bars, 20 μm; n = 4 in each group. Data were analyzed by unpaired t-test, **P < 0.01.

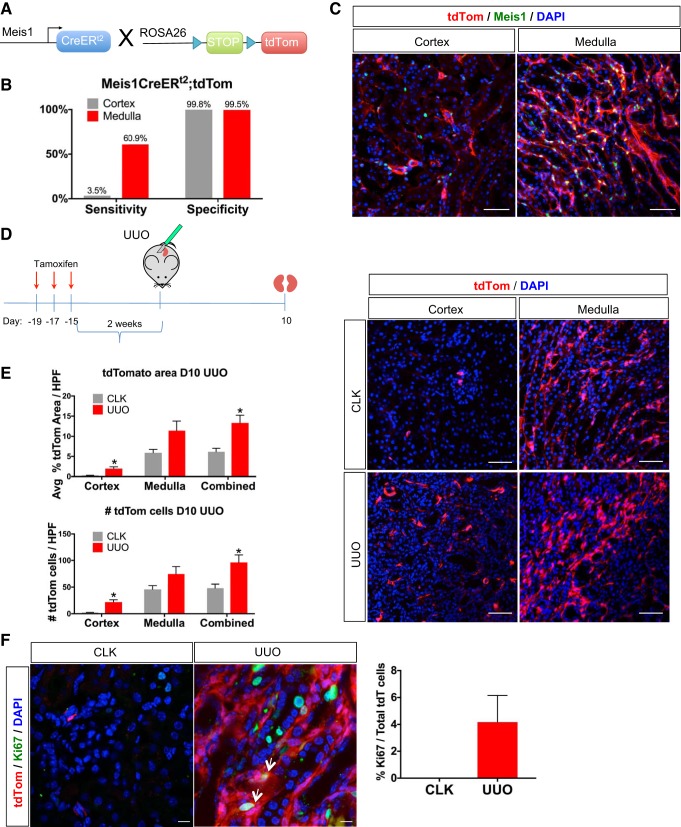

Fate tracing reveals that Meis1-positive cells proliferate after injury.

The increase in myofibroblast Meis1 expression after injury might reflect proliferative expansion of existing Meis1-positive cells, or alternatively de novo gain of Meis1 expression in previously Meis1-negative mesenchymal cells. To attempt to distinguish between these possibilities, we crossed a Meis1CreERt2 driver (13) to the R26tdTomato reporter mouse (Fig. 4A). We first assessed the sensitivity and specificity of this lineage-tracing model. Bigenic Meis1CreERt2;R26tdTomato mice were given tamoxifen (10 mg daily for 3 days), and mice were euthanized after a 2-wk washout period. We stained for endogenous Meis1 and also assessed tdTomato expression, and we quantified sensitivity and specificity of genetic labeling as described in methods. Labeling specificity was 99% in both cortex and medulla, and the sensitivity was 3.5% in the cortex and 61% in the medulla (Fig. 4, B and C). The low sensitivity almost certainly reflects low recombination efficiency.

Fig. 4.

Genetic lineage analysis shows proliferation of homeobox protein Meis1 (Meis1) cells after injury. A: breeding scheme. Meis1CreERt2 was crossed to the Rosa26tdTomato reporter mouse to generate a mouse in which tamoxifen induces labeling of Meis1-positive cells (CreER, Cre recombinase-estrogen receptor). B: the Meis1CreERt2 line was highly specific, but insensitive for recombination particularly in the cortex, using endogenous Meis1 expression as the gold standard. C: example of immunofluorescent staining with Meis1 antibody to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the mouse model. Scale bars, 50 μm. D and E: lineage tracing of bigenic Meis1CreERt2;R26tdTomato mice subjected to unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO; R26, Rosa26). Kidneys were harvested at day 10 (D10). Lineage tracing shows an increase in the percent tdTomato (tdTom) area of the UUO kidney indicating expansion of this population, especially in the cortex. An alternative quantification was done by counting the number of total tdTomato cells per high-power field (HPF) and shows the same trend of increased tdTomato cells in the cortex of the UUO kidney compared with the contralateral kidney (CLK). Immunofluorescence shows the increased expansion of tdTomato cells in both the cortex and medulla of the UUO kidney. Scale bars, 50 μm. Avg, average. In B, D, and E, n = 4. Data were analyzed by unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05. F: immunofluorescence staining for proliferation marker protein Ki-67 (Ki67) shows that at day 10 UUO, some tdTomato cells were still proliferating (arrows). Quantification of the number of Ki67-positive cells among the total number of tdTomato (tdT) cells is also shown. Scale bars, 10 μm; n = 3.

We followed the same tamoxifen dosing protocol but performed UUO surgery after a 2-wk washout. Kidneys were harvested at day 10. We quantified the number of tdTomato cells per high-power field in both CLK and UUO kidney (Fig. 4D). There was a statistically significant increase in the number of tdTomato cells in the cortex of the UUO kidney compared with CLK. A nonsignificant trend of increased tdTomato-positive cells was observed in the medulla. We also quantified proliferation by measuring the total percentage of tdTomato area and obtained similar results. Alternatively, when staining for the proliferation marker Ki67, ~4% of the total tdTomato cells were coexpressing Ki67 indicating that these cells were proliferating. The low percentage is likely due to the low recombination efficiency in the cortex, where more of the fibrosis takes place, and by day 10 after UUO, not much proliferation is expected. This suggests that at a minimum, Meis1-positive pericytes proliferate after injury as they differentiate into myofibroblasts. The large increase in cortical tdTomato-positive Meis1 cells raises the possibility that some of these arose from migration out of the medulla, where there are far more Meis1-positive cells to begin with, though we cannot distinguish this possibility from proliferation in situ.

Meis1 deletion did not have an effect on renal fibrosis.

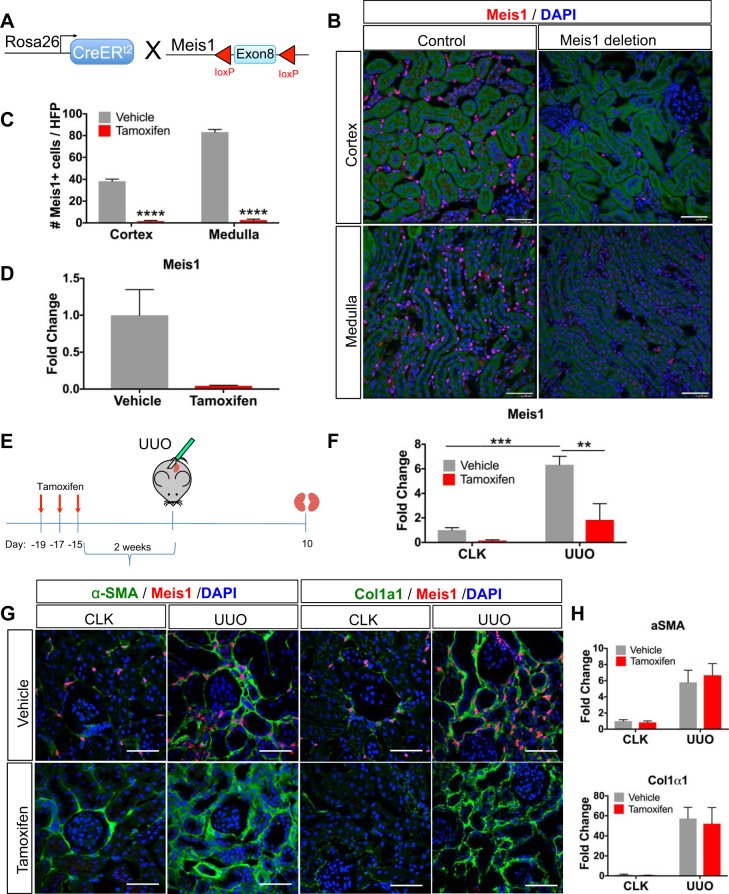

Given upregulation of Meis1 during pericyte-to-myofibroblast transition in two separate models of injury, as well as in aging, we next asked whether Meis1 was required for this process. Using a floxed Meis1 allele (37), we generated two separate models for conditional deletion of Meis1. In the first, we generated R26CreERt2;Meis1f/f bigenic mice to allow conditional deletion of Meis1 in all cells (Fig. 5A). We validated the mouse line by administering tamoxifen, 10 mg × 3 daily doses, to a cohort of bigenic mice. After a 2-wk washout period, the kidneys were collected, and immunofluorescence for Meis1 confirmed the nearly complete absence of Meis1 protein in kidney (Fig. 5, B and C). We quantitated loss of Meis1 mRNA by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using primers targeted to exon 8, and we observed an almost 90% decrease in Meis1 mRNA expression (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Deletion of homeobox protein Meis1 (Meis1) does not ameliorate renal fibrosis. A: Meis1f/f mice were crossed to the R26CreERt2 mouse (CreER, Cre recombinase-estrogen receptor; f/f, floxed/floxed; R26, Rosa26). Tamoxifen (10 mg) was administered for three doses, and mice were euthanized at 14 days after the last dose. Control group received vehicle. B: immunofluorescent staining for Meis1 shows lack of Meis1 staining in the Meis1-deleted kidney as expected after tamoxifen administration. Control kidney shows the expected interstitial Meis1 expression. Scale bars, 50 μm. C: quantification of the number of Meis1-positive cells after Meis1 deletion. HPF, high-power field. D: downregulation of Meis1 at the mRNA level after tamoxifen administration. E: experimental scheme showing timing for tamoxifen administration, surgery, and harvesting. F: Meis1 quantitative PCR (qPCR) showing decreased Meis1 mRNA expression in the tamoxifen group in both contralateral kidney (CLK) and unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) kidney. G: immunostaining for fibrosis markers α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and collagen-α1(I) (Col1α1) in both groups shows no difference in the extent of fibrosis after Meis1 deletion. Scale bars, 50 μm. H: α-SMA and Col1α1 qPCR showing no difference with Meis1 deletion. In C and D, n = 3 in each group; data were analyzed by unpaired t-test, ****P < 0.0001. In F, n = 5 in each group; data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by multiple-group comparison analysis with Tukey correction, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We next asked whether the absence of Meis1 had any effect on renal fibrosis. UUO was performed 2 wk after tamoxifen administration, and kidneys were collected 10 days after the surgery (Fig. 5E). Tamoxifen induced a nearly 90% reduction in Meis1 mRNA expression in the CLK. In the UUO kidney of the vehicle group, Meis1 was upregulated in a similar fashion to the response seen in wild-type mice that have sustained UUO. This induction was substantially abrogated in tamoxifen-treated mice (Fig. 5F). Despite good knockout of Meis1, immunofluorescent staining with fibrosis markers α-SMA and collagen-α1(I) (Col1α1) showed no difference between the Meis1-deleted group and the vehicle group (Fig. 5G). Measurement of mRNA by qPCR confirmed no difference in the levels of these fibrotic readouts in Meis1-deleted versus control mice (Fig. 5H). These findings do not provide evidence for a role of Meis1 in mediating renal fibrosis.

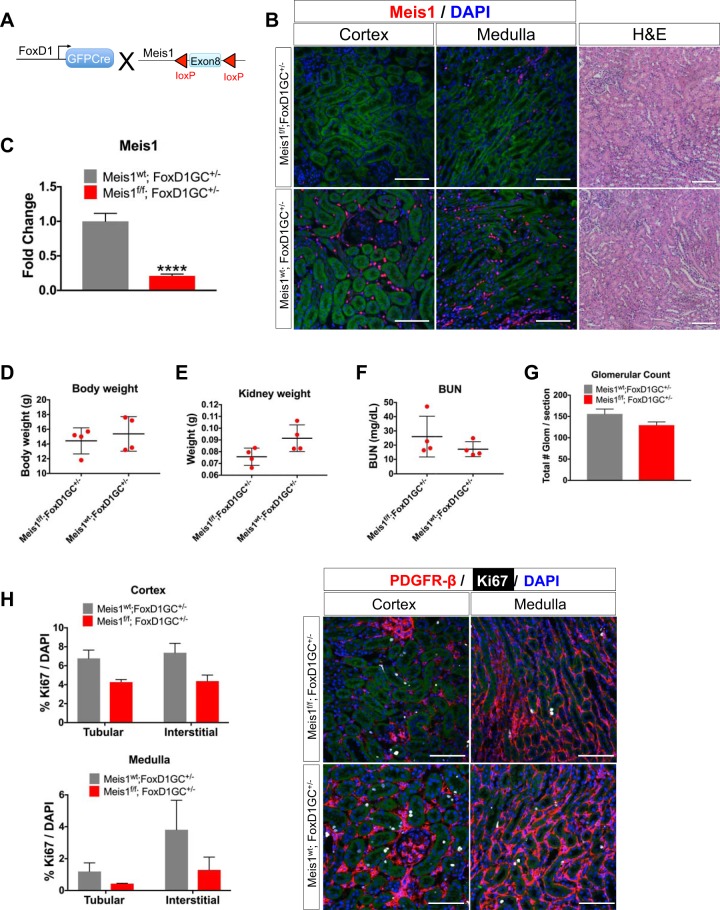

Stromal Meis1 is not required for kidney development.

Our inducible global deletion did not completely knock out Meis1, and also it deleted Meis1 in nonrenal tissues such as leukocytes that are known to express Meis1, possibly confounding interpretation of the results. For these reasons, we also generated a kidney-specific Meis1-deleted mouse using the FoxD1-GFPCre (FoxD1-GC) driver (Fig. 6A). This is active in nephrogenesis in stromal progenitors fated to become kidney mesenchyme (22). We generated cohorts of Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− and littermate controls (Meis1wt;FoxD1-GC+/−; wt, wild type). We obtained bigenic pups in the expected Mendelian distribution (39/175 = 22% of all matings). Kidneys were collected at postnatal day 30. We first validated the deletion by immunostaining with the Meis1 antibody (Fig. 6B). With this model, there was almost complete absence of Meis1 staining in the cortex and there were only a few remaining Meis1-expressing cells in the medulla in the Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/−, whereas there was the expected pattern of interstitial Meis1 expression in the control group. At the mRNA level, there was an almost 80% decrease in Meis1 expression (Fig. 6C). The decrease in Meis1 mRNA expression is slightly lower in the kidney-specific model compared with the global deletion model, possibly because of either the absence of recombination in leukocytes by the FoxD1-Cre driver or differences in recombination efficiency. There were no differences in body weight, kidney weight, BUN, or glomerular count between the groups (Fig. 6, D–G). Histological evaluation by hematoxylin-eosin and PAS stainings did not show any gross abnormalities. Finally, we observed no difference in tubular versus interstitial proliferation between groups (Fig. 6H). Although there seemed to be a difference in kidney weight and proliferation among the groups, they did not achieve statistical difference probably because of sample variation and need for higher power.

Fig. 6.

Stromal homeobox protein Meis1 (Meis1) deletion using FoxD1-GC [forkhead box D1-green fluorescent protein (GFP)-Cre] has no developmental phenotype. A: Meis1f/f mice were crossed to the FoxD1-GC mouse line to induce Meis1 deletion in the stroma (f/f, floxed/floxed). Kidneys were collected at postnatal day 30. B: immunofluorescent staining showing efficient Meis1 deletion in the kidney stroma; scale bars, 50 μm. Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining showing no gross morphological abnormalities in Meis1 deletion; scale bars, 100 μm. Here, wt, wild type. C: quantitative PCR showing downregulation of Meis1 mRNA expression in the Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− group. D–G: there was no difference in body weight, kidney weight, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), or glomerular count. Glom, glomeruli. H: immunofluorescent staining for proliferation marker protein Ki-67 (Ki67) showed no change in the proliferation of interstitial cells after Meis1 deletion. PDGFRβ, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β. Scale bars, 50 μm. In C, n = 6 in each group, and in D–G, n = 3–4 in each group. Data were analyzed by unpaired t-test, ****P < 0.0001.

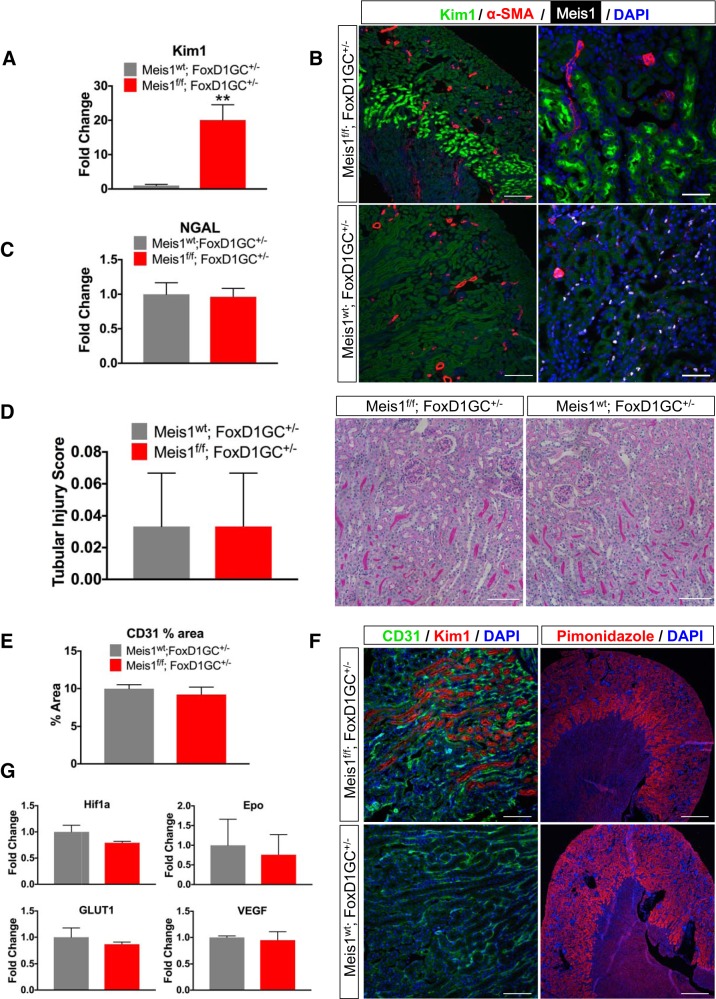

Meis1 deletion in the stroma apparently leads to Kim-1 upregulation.

Despite normal histology in kidney development, we unexpectedly observed strong and specific upregulation of the tubular injury marker Kim-1 in proximal tubules of mice with stromal Meis1 deletion. We tested this both by qPCR and by immunostaining with highly consistent results (Fig. 7, A and B). Since Kim-1 is a sensitive marker of tubular injury, we initially interpreted this result as evidence for Meis1-dependent proximal tubule dedifferentiation and/or injury mediated by paracrine signals sent out from Meis1-deleted adjacent stroma. We therefore searched carefully for other evidence of injury in Meis1-deleted kidneys. Surprisingly, however, a different tubular injury marker [neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL)] was completely normal in the same mice (Fig. 7C). Histological analysis of PAS kidney sections from both control and Meis1-deleted mice showed no evidence of injury as assessed by tubular injury score performed blindly. Similarly, glomerular counts and capillary area as measured by percentage area of CD31 staining were also not different between groups (Fig. 7, D–F). We considered hypoxia as a possible driver of Kim-1 upregulation; however, there was no difference in hypoxia markers such as hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (Hif1α), erythropoietin (Epo), glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), or VEGF by qPCR (Fig. 7G). Immunostaining with the hypoxia probe pimonidazole was also similar in both groups (Fig. 7F).

Fig. 7.

Homeobox protein Meis1 (Meis1) deletion in the stroma leads to apparent, spontaneous kidney injury molecule-1 (Kim-1) expression in outer medulla. A: quantitative PCR (qPCR) showing upregulation of Kim-1 in the Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− group (f/f, floxed/floxed; FoxD1-GC, forkhead box D1-green fluorescent protein-Cre; wt, wild type). B: immunofluorescent staining showing Kim-1 expression in the outer stripe of the medulla in Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− mice, but not in the Meis1wt;FoxD1-GC+/− (control) group. α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin. For zoom ×10, scale bars are 200 μm; for zoom ×40, scale bars are 50 μm. C: there is no difference in the neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) mRNA expression between the groups. D: tubular injury score and period acid-Schiff staining showed no evidence of injury in either of the groups. Scale bars, 100 μm. E–G: immunofluorescent staining for platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (CD31) to evaluate capillary density and pimonidazole staining to evaluate for hypoxia. No difference was observed when quantifying the average percent area of CD31. There was no difference in hypoxia markers hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (Hif1α), erythropoietin (Epo), glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), or VEGF by qPCR. For zoom ×20, scale bars are 100 μm; for zoom ×4, scale bars are 500 μm. Here, n = 4–6 in each group. Data were analyzed by unpaired t-test, **P < 0.01.

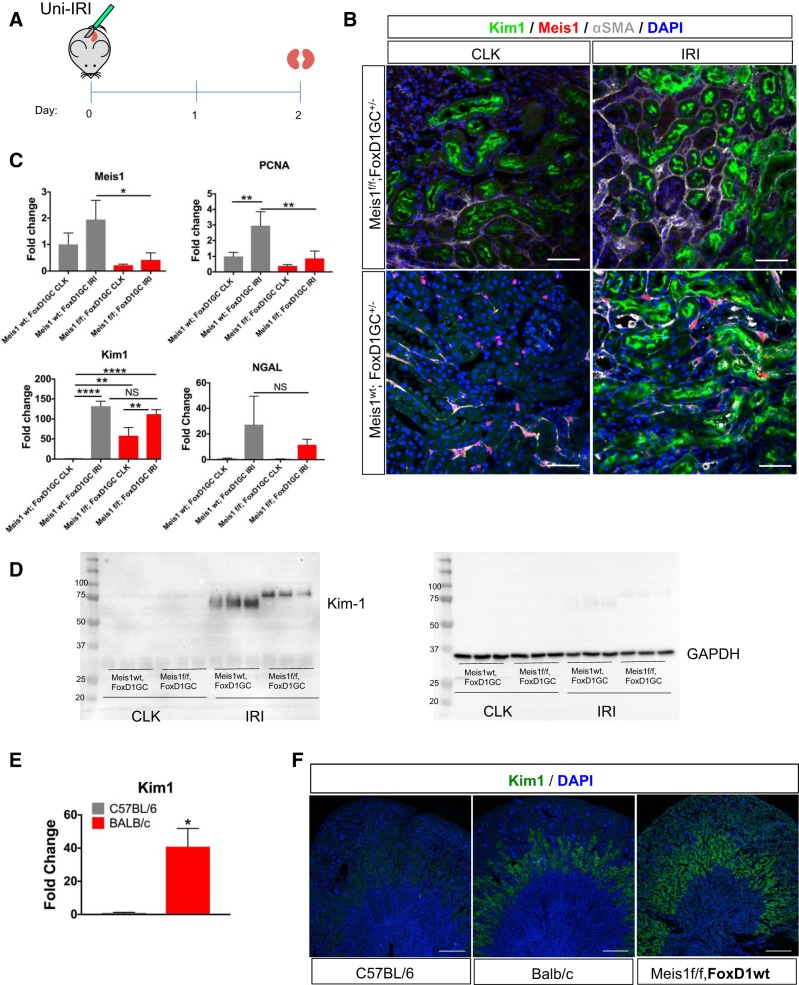

We also asked whether kidneys that already expressed Kim-1 at baseline might be more susceptible to ischemic injury. To evaluate this, we performed Uni-IRI in a group of male Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− and compared with Meis1wt;FoxD1-GC+/− as controls. Kidneys were collected 2 days after surgery. The CLK served as an internal control to the baseline level of Kim-1. There was an ~80% decrease in Meis1 mRNA expression in the Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− group similar to our previous protocols. By immunostaining, there was no major difference in the level of Kim-1 expression between the groups, and this was also the case at the mRNA level (Fig. 8, A–C). Though NGAL mRNA upregulation was less in the Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− IRI kidney compared with control IRI kidney, this did not achieve statistical difference because of sample variation in the control group.

Fig. 8.

Despite baseline kidney injury molecule-1 (Kim-1) expression in the homeobox protein Meis1 (Meis1)-deleted group, there was no effect on the injury response. A: Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− mice were subjected to unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury (Uni-IRI), and kidneys were collected at day 2 after surgery (f/f, floxed/floxed; FoxD1-GC, forkhead box D1-green fluorescent protein-Cre). B: immunostaining for Kim-1 and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) showed no overall difference in the extent of injury in the Meis1-deleted group. Scale bars, 50 μm; wt, wild type. C: quantitative PCR (qPCR) for Meis1 confirming the Meis1 downregulation in the Meis1f/f group. There was no difference in Kim-1 or neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) mRNA expression. There is downregulation of PCNA in the Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− IRI kidney. D: Western blot for Kim-1 (expected size 70–80 kDa) in the contralateral kidney (CLK) and Uni-IRI samples for both Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− and Meis1wt;FoxD1-GC+/− groups. Notice the slightly higher band for Kim-1 in the IRI group of the Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− group compared with control. GAPDH was used as loading control. E: qPCR showing increased Kim-1 mRNA expression at baseline in BALB/c mice compared with C57BL/6 mice. F: immunofluorescent staining for Kim-1 in C57BL/6, BALB/c, and Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GCwt. Notice the presence of Kim-1 expression in the outer medulla of the kidney of the Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GCwt mouse, which is similar to the baseline expression in the kidney of the BALB/c mouse. There is no Kim-1 expression at baseline in the C57BL/6 mouse kidney. Scale bars, 500 μm. In C, n = 3 in each group; data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by multiple-group comparison analysis with Tukey correction, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant. In E, n = 4 in each group; data were analyzed by unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05.

The completely normal kidney phenotype and response to injury in Meis1-deleted kidneys, despite increased baseline Kim-1 expression, led us to investigate the Kim-1 protein being expressed. We then discovered that the Kim-1 protein in the injured kidney of the Meis1-deleted group was slightly larger compared with the injured kidney from the control group (Fig. 8D). Polymorphic alleles do exist for Kim-1: the BALB/c allele encodes a 305-amino acid protein, whereas the DBA/2 strain (which is close to the C57BL/6 strain) encodes for a protein with a 15-amino acid deletion (30). However, the segregation of alleles was unexpected since both Meis1-deleted and control lines were on a mixed background. We therefore examined the genomic location of the Kim-1 and Meis1 genes and discovered that they are both on chromosome 11, separated by ~27 megabases. This strongly suggests that our Meis1 floxed allele is in linkage disequilibrium with the larger BALB/c allele for Kim-1 and that this larger allele is expressed at baseline, in healthy kidneys, in sharp distinction with the smaller DBA/2 allele.

To test our hypothesis, we obtained kidneys from young C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice, measured Kim-1 mRNA expression by qPCR, and stained for Kim-1 (Fig. 8, E and F). Surprisingly, we observed baseline Kim-1 expression in the kidney of wild-type BALB/c mice in exactly the same outer medullary location we observed in our Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− kidneys. No Kim-1 staining was observed in the kidneys of the C57BL/6 mice. In addition, we also stained kidney sections of Meis1f/f mice without the FoxD1-GC allele and observed the same pattern of Kim-1 expression in the outer medulla (Fig. 8F). We conclude that there is basal expression of Kim-1 protein in BALB/c mice and that Meis1 and Kim-1 were in linkage disequilibrium in our genetic models.

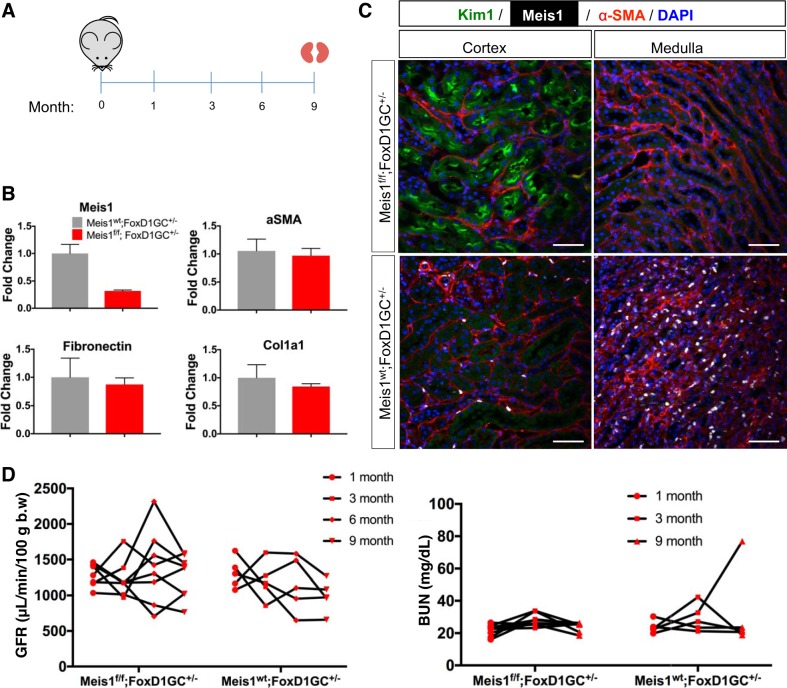

Stroma-specific deletion of Meis1 did not alter the fibrotic process over time.

To complete our analysis, we also evaluated whether Meis1 deletion might lead to a kidney phenotype that was only revealed with aging. We collected blood and measured the GFR from Meis1-deleted or control mice at 1, 3, 6, and 9 mo (Fig. 9A) and harvested the kidneys after 9 mo. We confirmed that there was still downregulation of Meis1 by qPCR (Fig. 9B) in the Meis1-deleted group. Evaluation by mRNA showed that there was no change in the fibrosis markers α-SMA, fibronectin, or Col1α1. Immunofluorescence staining showed that there was no change in α-SMA staining. There was still presence of Kim-1 in the Meis1-deleted group as previously shown in the younger group (Fig. 9C). We did not observe any difference in the renal function as assessed by GFR or BUN measurements in the Meis1-deleted group compared with controls (Fig. 9D).

Fig. 9.

Stromal homeobox protein Meis1 (Meis1) deletion does not alter kidney aging. A: Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− mice and littermate controls were followed over time (f/f, floxed/floxed; FoxD1-GC, forkhead box D1-green fluorescent protein-Cre). Blood collection and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) measurements were done at 1, 3, 6, and 9 mo. B: quantitative PCR for Meis1 showing downregulation as expected in the Meis1f/f group. There was no difference at the mRNA level of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), fibronectin, or collagen-α1(I) (Col1α1). Here, wt, wild type. C: immunostaining showing no difference in α-SMA expression between the groups. There is persistent kidney injury molecule-1 (Kim-1) expression in the Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/− group as previously shown. Scale bars, 50 μm. D: graphs showing the GFR and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) measurements at the stated time points for both groups; b.w., body weight. Meis1wt;FoxD1-GC+/−, n = 3; Meis1f/f;FoxD1-GC+/−, n = 6.

DISCUSSION

There are three main conclusions concerning kidney Meis1 from our study. First, Meis1 expression is expressed primarily in perivascular fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in mouse and human kidney, though it is only expressed in a small subset of healthy human kidney fibroblasts and pericytes. Second, acute and chronic injury and aging increase Meis1 expression specifically in kidney myofibroblasts during their differentiation and proliferation. Third, Meis1 is not required for normal kidney development or aging, and its absence has no effect on murine kidney fibrosis.

Although Meis1 is known as a marker of interstitial stroma in developing kidney and in human kidney organoids (8, 17, 35), no study to date has characterized its expression in adults or after injury. Our findings here indicate that Meis1 is a possible marker of pericytes and perivascular fibroblasts in health and of myofibroblasts in fibrosis and aging. We never observed Meis1 expression in tubular epithelium and only very rarely observed expression in other cell types such as endothelial cells or macrophages, further emphasizing its utility as a stromal marker. As a nuclear protein, Meis1 also lends itself to quantitation of cell number, since kidney stroma have long branched and overlapping cytoplasmic processes, making cell quantitation a challenge.

This is the first study to show that Meis1 is upregulated with kidney injury and aging. A prior work reported higher levels of Meis1 during nephrogenesis than in adult kidney; however, injury models and aging were not examined (9). Our lineage analysis demonstrates that Meis1-positive stromal progenitors proliferate and differentiate into myofibroblasts. We have previously defined zinc finger protein GLI1 (Gli1) as a specific marker of myofibroblast progenitors in kidney (12, 23, 24). Since Meis1 expression is widespread through renal interstitium and tracks closely with PDGFRβ expression, we speculate that Gli1 is expressed in a smaller subset of Meis1-positive renal stroma. We were unable to test this hypothesis because of the absence of a suitable Gli1 antibody, but the lineage-tracing results are consistent with overlapping Meis1 and Gli1 expression domains.

The specific expression of Meis1 in kidney stroma during development and its upregulation in injury and kidney aging suggested to us a possible role in stromal development and differentiation. Two separate models of Meis1 deletion, a global deletion model and stroma-specific model, both failed to show any kidney phenotype in development, homeostasis, injury response, and aging. We hypothesize that other regulatory pathways compensate for the absence of Meis1. Other Meis family members exist including Meis2 and Meis3 (16), and previous studies have suggested linked expression between Meis family members. For example, knockdown of Meis2 in a leukemia cell line caused 10-fold decreased Meis1 expression (26). It has been observed that mice with conditional deletion of Meis1 still populate all hematopoietic lineages suggesting that other Meis1 family members such as Meis2 can compensate for the lack of Meis1 (1, 15). This redundancy among the Meis1 family members might account for our lack of observed kidney phenotype, although whether Meis2 or Meis3 is expressed in kidney is unknown. Meis proteins form stable heteromeric complexes with other transcriptional regulators, enhancing their affinity and specificity of binding to DNA sites in the target gene locus. In the case of Meis1, it partners with pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor 1 (PBX1) because of lack of a nuclear localization signal (3). Therefore, it is also possible that in order to see an effect in Meis1, simultaneous knockdown of its binding partner might be required.

Our characterization of Meis1 mutants revealed the unexpected finding that all Meis1f/f mice have baseline expression of Kim-1 in normal kidney and that this Kim-1 allele is the 15 amino acid-longer BALB/c allele. Our explanation for this finding is that the Meis1 gene is in linkage disequilibrium with the Kim-1 gene, since they are located near each other on chromosome 11. That wild-type BALB/c mice also express Kim-1 in healthy kidney, as we show here, strongly supports this interpretation. Kim-1 has been extensively characterized as a molecule only expressed after injury, when it acts as a phosphatidylserine receptor and converts epithelial cells into phagocytes to clear the tubular lumen of apoptotic cell debris (5, 21). To our knowledge, this BALB/c phenotype has not yet been explicitly reported. However, we have noticed a study where there is a faint band in a Kim-1 Western blot experiment on uninjured BALB/c mouse kidneys (28), consistent with our findings here.

We have previously shown that tubular overexpression of Kim-1 using a genetic model (Kim1RECtg mice; Kim1 renal epithelial cell transgenic) is sufficient to drive fibrosis and progressive kidney disease (20). In distinct contrast, neither our Meis1 mutants nor wild-type BALB/c mice develop renal fibrosis despite persistent Kim-1 expression in the outer medullary proximal tubule. It should be noted that Kim1RECtg were designed to overexpress the shorter DBA allele, so one possible explanation for these divergent results is that the additional 15 amino acids located in the mucin domain of Kim-1 confer protection against its profibrotic effects. Indeed, the mucin domain has been shown to exert potent suppressive effects on regulatory B cells (20, 38). Alternatively, expression level may account for these differences, since Kim1RECtg utilized the strong CAG promoter. Further studies are required to understand the genetic elements that regulate baseline expression on the BALB/c background and the reasons for the absence of any associated fibrotic phenotype.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Grants DK-107274, DK-103740, DK-107374, and DK-103050; by an Established Investigator Award of the American Heart Association to B. D. Humphreys; and by NIDDK Grant F32-DK-103441 to M. Chang-Panesso.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.C.-P. and B.D.H. conceived and designed research; M.C.-P., F.F.K., and F.G.M. performed experiments; M.C.-P., F.F.K., F.G.M., and B.D.H. analyzed data; M.C.-P., F.F.K., F.G.M., and B.D.H. interpreted results of experiments; M.C.-P. prepared figures; M.C.-P. and B.D.H. drafted manuscript; M.C.-P., F.F.K., and B.D.H. edited and revised manuscript; M.C.-P., F.F.K., F.G.M., A.K., and B.D.H. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Dr. Miguel Torres for kindly donating the Meis1CreERt2 and Meis1-eCFP mouse lines. Also, we thank Lucy Fan for management of the mouse breeding.

REFERENCES

- 1.Argiropoulos B, Yung E, Humphries RK. Unraveling the crucial roles of Meis1 in leukemogenesis and normal hematopoiesis. Genes Dev 21: 2845–2849, 2007. doi: 10.1101/gad.1619407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azcoitia V, Aracil M, Martínez-A C, Torres M. The homeodomain protein Meis1 is essential for definitive hematopoiesis and vascular patterning in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol 280: 307–320, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasi F, Bruckmann C, Penkov D, Dardaei L. A tale of TALE, PREP1, PBX1, and MEIS1: interconnections and competition in cancer. BioEssays 39: 1600245, 2017. doi: 10.1002/bies.201600245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun H, Schmidt BM, Raiss M, Baisantry A, Mircea-Constantin D, Wang S, Gross ML, Serrano M, Schmitt R, Melk A. Cellular senescence limits regenerative capacity and allograft survival. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1467–1473, 2012. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011100967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks CR, Yeung MY, Brooks YS, Chen H, Ichimura T, Henderson JM, Bonventre JV. KIM-1-/TIM-1-mediated phagocytosis links ATG5-/ULK1-dependent clearance of apoptotic cells to antigen presentation. EMBO J 34: 2441–2464, 2015. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunskill EW, Aronow BJ, Georgas K, Rumballe B, Valerius MT, Aronow J, Kaimal V, Jegga AG, Yu J, Grimmond S, McMahon AP, Patterson LT, Little MH, Potter SS. Atlas of gene expression in the developing kidney at microanatomic resolution. Dev Cell 15: 781–791, 2008. [Erratum in Dev Cell 16: 482, 2009.] 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crijns AP, de Graeff P, Geerts D, Ten Hoor KA, Hollema H, van der Sluis T, Hofstra RM, de Bock GH, de Jong S, van der Zee AG, de Vries EG. MEIS and PBX homeobox proteins in ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer 43: 2495–2505, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Das A, Tanigawa S, Karner CM, Xin M, Lum L, Chen C, Olson EN, Perantoni AO, Carroll TJ. Stromal-epithelial crosstalk regulates kidney progenitor cell differentiation. Nat Cell Biol 15: 1035–1044, 2013. [Erratum in Nat Cell Biol 15: 1260, 2013. 10.1038/ncb2853.] 10.1038/ncb2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dekel B, Metsuyanim S, Schmidt-Ott KM, Fridman E, Jacob-Hirsch J, Simon A, Pinthus J, Mor Y, Barasch J, Amariglio N, Reisner Y, Kaminski N, Rechavi G. Multiple imprinted and stemness genes provide a link between normal and tumor progenitor cells of the developing human kidney. Cancer Res 66: 6040–6049, 2006. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiRocco DP, Bisi J, Roberts P, Strum J, Wong KK, Sharpless N, Humphreys BD. CDK4/6 inhibition induces epithelial cell cycle arrest and ameliorates acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F379–F388, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00475.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edeling M, Ragi G, Huang S, Pavenstädt H, Susztak K. Developmental signalling pathways in renal fibrosis: the roles of Notch, Wnt and Hedgehog. Nat Rev Nephrol 12: 426–439, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fabian SL, Penchev RR, St-Jacques B, Rao AN, Sipilä P, West KA, McMahon AP, Humphreys BD. Hedgehog-Gli pathway activation during kidney fibrosis. Am J Pathol 180: 1441–1453, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.González-Lázaro M, Roselló-Díez A, Delgado I, Carramolino L, Sanguino MA, Giovinazzo G, Torres M. Two new targeted alleles for the comprehensive analysis of Meis1 functions in the mouse. Genesis 52: 967–975, 2014. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrera Pérez Z, Weinfurter S, Gretz N. Transcutaneous assessment of renal function in conscious rodents. J Vis Exp 109: e53767, 2016. doi: 10.3791/53767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hisa T, Spence SE, Rachel RA, Fujita M, Nakamura T, Ward JM, Devor-Henneman DE, Saiki Y, Kutsuna H, Tessarollo L, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. Hematopoietic, angiogenic and eye defects in Meis1 mutant animals. EMBO J 23: 450–459, 2004. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang H, Rastegar M, Bodner C, Goh SL, Rambaldi I, Featherstone M. MEIS C termini harbor transcriptional activation domains that respond to cell signaling. J Biol Chem 280: 10119–10127, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413963200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hum S, Rymer C, Schaefer C, Bushnell D, Sims-Lucas S. Ablation of the renal stroma defines its critical role in nephron progenitor and vasculature patterning. PLoS One 9: e88400, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humphreys BD. Mechanisms of renal fibrosis. Annu Rev Physiol 80: 309–326, 2018. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphreys BD, Lin SL, Kobayashi A, Hudson TE, Nowlin BT, Bonventre JV, Valerius MT, McMahon AP, Duffield JS. Fate tracing reveals the pericyte and not epithelial origin of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Am J Pathol 176: 85–97, 2010. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humphreys BD, Xu F, Sabbisetti V, Grgic I, Movahedi Naini S, Wang N, Chen G, Xiao S, Patel D, Henderson JM, Ichimura T, Mou S, Soeung S, McMahon AP, Kuchroo VK, Bonventre JV. Chronic epithelial kidney injury molecule-1 expression causes murine kidney fibrosis. J Clin Invest 123: 4023–4035, 2013. doi: 10.1172/JCI45361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ichimura T, Asseldonk EJ, Humphreys BD, Gunaratnam L, Duffield JS, Bonventre JV. Kidney injury molecule-1 is a phosphatidylserine receptor that confers a phagocytic phenotype on epithelial cells. J Clin Invest 118: 1657–1668, 2008. doi: 10.1172/JCI34487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi A, Mugford JW, Krautzberger AM, Naiman N, Liao J, McMahon AP. Identification of a multipotent self-renewing stromal progenitor population during mammalian kidney organogenesis. Stem Cell Reports 3: 650–662, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramann R, Fleig SV, Schneider RK, Fabian SL, DiRocco DP, Maarouf O, Wongboonsin J, Ikeda Y, Heckl D, Chang SL, Rennke HG, Waikar SS, Humphreys BD. Pharmacological GLI2 inhibition prevents myofibroblast cell-cycle progression and reduces kidney fibrosis. J Clin Invest 125: 2935–2951, 2015. doi: 10.1172/JCI74929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kramann R, Schneider RK, DiRocco DP, Machado F, Fleig S, Bondzie PA, Henderson JM, Ebert BL, Humphreys BD. Perivascular Gli1+ progenitors are key contributors to injury-induced organ fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell 16: 51–66, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishnamurthy J, Torrice C, Ramsey MR, Kovalev GI, Al-Regaiey K, Su L, Sharpless NE. Ink4a/Arf expression is a biomarker of aging. J Clin Invest 114: 1299–1307, 2004. doi: 10.1172/JCI22475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai CK, Norddahl GL, Maetzig T, Rosten P, Lohr T, Sanchez Milde L, von Krosigk N, Docking TR, Heuser M, Karsan A, Humphries RK. Meis2 as a critical player in MN1-induced leukemia. Blood Cancer J 7: e613, 2017. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2017.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawrence HJ, Rozenfeld S, Cruz C, Matsukuma K, Kwong A, Kömüves L, Buchberg AM, Largman C. Frequent co-expression of the HOXA9 and MEIS1 homeobox genes in human myeloid leukemias. Leukemia 13: 1993–1999, 1999. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim AI, Chan LY, Lai KN, Tang SC, Chow CW, Lam MF, Leung JC. Distinct role of matrix metalloproteinase-3 in kidney injury molecule-1 shedding by kidney proximal tubular epithelial cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 44: 1040–1050, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahmoud AI, Kocabas F, Muralidhar SA, Kimura W, Koura AS, Thet S, Porrello ER, Sadek HA. Meis1 regulates postnatal cardiomyocyte cell cycle arrest. Nature 497: 249–253, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nature12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McIntire JJ, Umetsu SE, Akbari O, Potter M, Kuchroo VK, Barsh GS, Freeman GJ, Umetsu DT, DeKruyff RH. Identification of Tapr (an airway hyperreactivity regulatory locus) and the linked Tim gene family. Nat Immunol 2: 1109–1116, 2001. doi: 10.1038/ni739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melk A, Schmidt BM, Braun H, Vongwiwatana A, Urmson J, Zhu LF, Rayner D, Halloran PF. Effects of donor age and cell senescence on kidney allograft survival. Am J Transplant 9: 114–123, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melk A, Schmidt BM, Takeuchi O, Sawitzki B, Rayner DC, Halloran PF. Expression of p16INK4a and other cell cycle regulator and senescence associated genes in aging human kidney. Kidney Int 65: 510–520, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moskow JJ, Bullrich F, Huebner K, Daar IO, Buchberg AM. Meis1, a PBX1-related homeobox gene involved in myeloid leukemia in BXH-2 mice. Mol Cell Biol 15: 5434–5443, 1995. doi: 10.1128/MCB.15.10.5434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sis B, Tasanarong A, Khoshjou F, Dadras F, Solez K, Halloran PF. Accelerated expression of senescence associated cell cycle inhibitor p16INK4A in kidneys with glomerular disease. Kidney Int 71: 218–226, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takasato M, Little MH. A strategy for generating kidney organoids: Recapitulating the development in human pluripotent stem cells. Dev Biol 420: 210–220, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thorsteinsdottir U, Kroon E, Jerome L, Blasi F, Sauvageau G. Defining roles for HOX and MEIS1 genes in induction of acute myeloid leukemia. Mol Cell Biol 21: 224–234, 2001. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.1.224-234.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unnisa Z, Clark JP, Roychoudhury J, Thomas E, Tessarollo L, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Grimes HL, Kumar AR. Meis1 preserves hematopoietic stem cells in mice by limiting oxidative stress. Blood 120: 4973–4981, 2012. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-435800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiao S, Brooks CR, Zhu C, Wu C, Sweere JM, Petecka S, Yeste A, Quintana FJ, Ichimura T, Sobel RA, Bonventre JV, Kuchroo VK. Defect in regulatory B-cell function and development of systemic autoimmunity in T-cell Ig mucin 1 (Tim-1) mucin domain-mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 12105–12110, 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120914109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]