Abstract

Stress-induced strand breaks in rRNA have been observed in many organisms, but the mechanisms by which they originate are not well-understood. Here we show that a chemical rather than an enzymatic mechanism initiates rRNA cleavages during oxidative stress in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). We used cells lacking the mitochondrial glutaredoxin Grx5 to demonstrate that oxidant-induced cleavage formation in 25S rRNA correlates with intracellular iron levels. Sequestering free iron by chemical or genetic means decreased the extent of rRNA degradation and relieved the hypersensitivity of grx5Δ cells to the oxidants. Importantly, subjecting purified ribosomes to an in vitro iron/ascorbate reaction precisely recapitulated the 25S rRNA cleavage pattern observed in cells, indicating that redox activity of the ribosome-bound iron is responsible for the strand breaks in the rRNA. In summary, our findings provide evidence that oxidative stress–associated rRNA cleavages can occur through rRNA strand scission by redox-active, ribosome-bound iron that potentially promotes Fenton reaction–induced hydroxyl radical production, implicating intracellular iron as a key determinant of the effects of oxidative stress on ribosomes. We propose that iron binding to specific ribosome elements primes rRNA for cleavages that may play a role in redox-sensitive tuning of the ribosome function in stressed cells.

Keywords: RNA, RNA degradation, ribosome, reactive oxygen species (ROS), oxidative stress, iron, iron metabolism, cell death, yeast, Fenton reaction, glutaredoxin, iron homeostasis

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)2 are omnipresent stressors for all biological systems. Low levels of ROS play roles in many biochemical processes and act as signaling molecules, but at supraphysiological levels, ROS can damage cellular components, including lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids (1, 2). Through oxidation of rRNA and proteins, ROS can influence the functionality of ribosomes, the complex ribonucleoprotein machines responsible for protein synthesis. For example, translation by the bacterial ribosome is inhibited by oxidation of the rRNA bases within the peptidyl transferase center (3). Reversible oxidation of cysteine residues in ribosome-associated proteins under conditions of increased ROS generation has been proposed to attenuate translation (4). Oxidative damage to rRNA has been hypothesized to play a role in neurodegenerative disease (5, 6). However, despite the central role of the ribosome in protein synthesis, our understanding of the impact of ROS on ribosome functions is still very limited.

In our previous work (7), we found that low, survivable levels of oxidative stress in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae lead to rRNA cleavages in a subset of cytoplasmic ribosomes. One prominent cleavage, located in the ES7 region of 25S rRNA in the large (60S) ribosomal subunit, starts at early stages of the adaptive oxidative stress response that helps cells to cope with ROS accumulation. The ES7 region is located on the surface of the 60S subunit and is one of the largest rRNA expansion clusters in the eukaryotic ribosome (8, 9). ES7-cleaved ribosomes are capable of reinitiating translation, suggesting that this type of rRNA cleavage does not inactivate ribosomes and may instead play a role in modulating their function during stress (7).

Aside from adaptable oxidative stress conditions, excessive ROS accumulation is a hallmark feature of apoptosis (10, 11). Induction of programmed cell death in various organisms has been shown to involve degradation of rRNA, presumably carried out by nucleases activated as part of apoptotic mechanisms (12–14). The identity of eukaryotic ribonucleases that initiate ribosome degradation during programmed cell death has remained uncertain.

In this study, we took advantage of the rapid yeast rRNA analysis techniques we developed recently (15) to survey genes encoding ribonucleases and proteins with function in redox regulation for possible effects on the ES7 cleavage in 25S rRNA. Unexpectedly, we found that the cellular control of iron but not ROS levels was the major determining factor in rRNA fragmentation during oxidative stress. Genetic and biochemical analyses confirmed that oxidant-induced cleavage of yeast rRNA is a nonenzymatic, iron-dependent process. Our results identify a previously unknown mechanism of site-specific changes in the ribosome that may have a biologically significant role in diverse oxidative stress conditions and during programmed cell death.

Results

Deletion of the monothiol glutaredoxin gene GRX5 causes severe rRNA degradation in yeast exposed to low-level oxidants

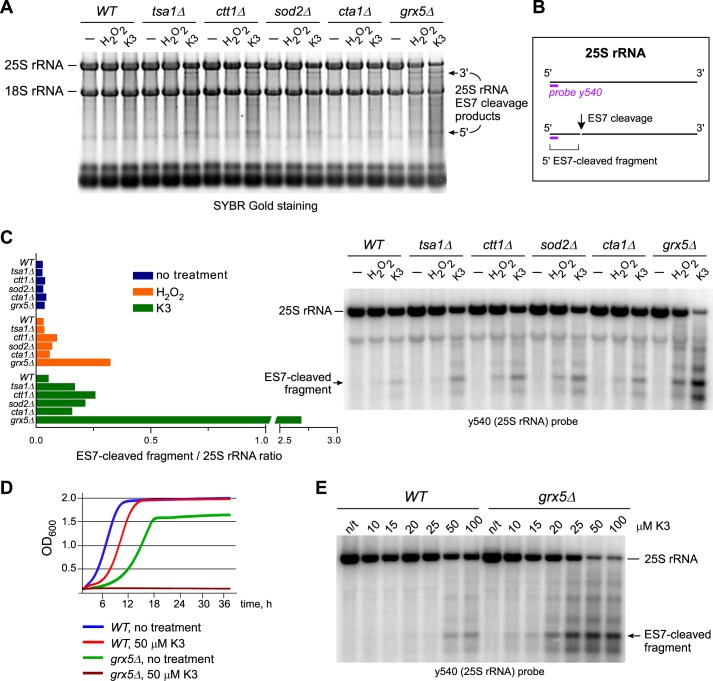

Previously, we identified cleavage in the expansion segment ES7 of the 25S rRNA as one of early molecular responses to elevated ROS levels in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae (7). To better understand cellular factors that affect ES7 cleavage, we screened a panel of ∼150 yeast strains deficient for antioxidant and oxidative stress–related genes as well as genes that encode various RNases. After growing cells to mid-log phase, we induced oxidative stress with low doses of inorganic peroxide (H2O2, 0.25 mm) or the redox-cycling agent menadione (vitamin K3, 50 μm) and isolated total RNA from the cells (15). Fig. 1A shows a representative set of five strains that were either left untreated or treated with the oxidants and compared with the WT BY4741 control. A number of deletion strains in our test panel showed increased accumulation of stress-induced RNA fragments, including products of ES7 cleavage in 25S rRNA (7), consistent with the involvement of multiple antioxidant systems in the cellular neutralization of ROS. To compare the strength of this phenotype in different strains, we performed Northern hybridizations with the probe y540, which detects both full-length 25S rRNA and the well-resolved 5′ fragment (∼600 nt) produced by ES7 cleavage (Fig. 1B) and determined the ES7 fragment/25S ratio in each lane (Fig. 1C). Control measurements in biological replicates showed that using this ratio minimizes variations resulting from loading and strain-specific differences in rRNA content. Among all tested mutants, deletion of the monothiol glutaredoxin gene GRX5 led to a particularly strong loss of rRNA stability in response to both H2O2 and menadione (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Treatment of grx5Δ cells with oxidants leads to extensive rRNA degradation and growth inhibition. A, increased rRNA degradation in strains deficient for antioxidant genes. Cells in mid-log phase were either left untreated (−) or treated with 50 μm menadione (K3) for 2 h or with 0.25 mm H2O2 for 30 min. Equal amounts of total RNA were separated on an agarose gel and stained with SYBR Gold. B, schematic representation of the sites of ES7 cleavage and probe y540 hybridization in 25S rRNA. C, cells lacking GRX5 demonstrate extensive ES7 cleavage in 25S rRNA. The same RNA samples as shown in A were analyzed by Northern hybridization with the 32P-labeled probe y540. Ratios of the ES7 cleavage 5′ fragment to full-length 25S rRNA (left panel) were obtained by phosphorimaging quantification of the corresponding bands (right panel). D, growth of grx5Δ cells is inhibited by 50 μm menadione. Mid-log cultures were diluted to A600 ∼0.1 and grown at 30 °C with shaking in YPDA in the absence or presence of 50 μm menadione. A600 of the cultures was measured every 5 min for 36 h, and representative growth curves are shown. E, ES7-cleaved fragment formation is detectable in a grx5Δ strain at lower menadione concentrations than in the WT. WT and grx5Δ cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of menadione for 2 h. 25S rRNA was analyzed as in C.

To ensure that the observed 25S rRNA degradation phenotype was due to lack of GRX5 rather than any secondary mutations that may have accumulated in a passaged knockout library strain, we backcrossed grx5Δ with WT BY4741 cells and generated several new grx5Δ strains by tetrad dissection. The newly derived grx5Δ strains were viable; however, they grew noticeably slower than the WT in fermentation medium (Fig. 1D). In agreement with a previous study (16), grx5Δ strains were deficient in respiration (Fig. S1A). Genetic tests and analysis of mitochondrial DNA showed grx5Δ cells to be ρ0 (Fig. S1, B–D), explaining their respiration deficiency. Testing the new grx5Δ strains confirmed their high sensitivity to oxidants. For example, grx5Δ cells were unable to grow in medium supplemented with 50 μm menadione, a dose that caused only a transient growth delay in the WT (Fig. 1D). Consistent with the screen data (Fig. 1C), Northern hybridization with the probe y540 showed severe 25S rRNA degradation in grx5Δ cells after treatment with either 0.25 mm H2O2 or 50 μm menadione (Fig. S2A). The ES7-cleaved fragment was detectable in grx5Δ cells after treatment with as little as 10 μm menadione, whereas 25S rRNA integrity in WT cells was unaffected by this dose (Fig. 1E).

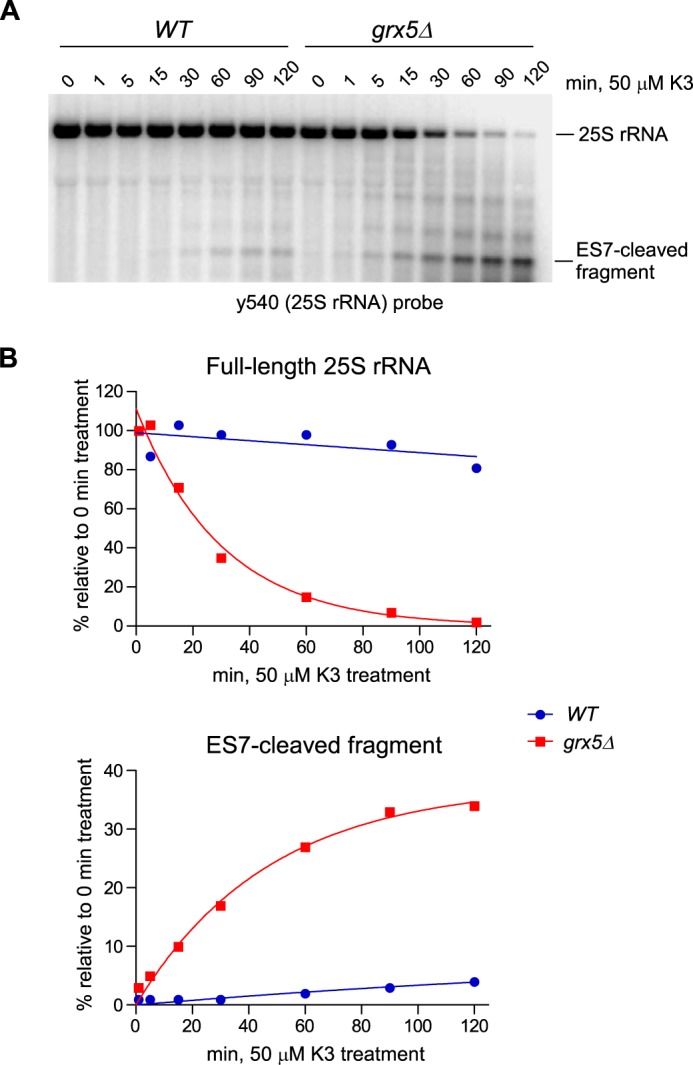

To better define the kinetics of the oxidant-induced 25S rRNA decay, we next analyzed rRNA at different time points after addition of 50 μm menadione to the culture medium (Fig. 2A). In grx5Δ cells, the ES7-cleaved fragment was apparent after a 1-min treatment and further increased in intensity over time, paralleled by decay of the full-length 25S rRNA (Fig. 2). By comparison, menadione treatment in WT cells led to a slower onset of rRNA degradation and affected only a small fraction of ribosomes (Fig. 2). This indicated that cleavage of the ES7 region of 25S rRNA occurs virtually instantaneously upon oxidant exposure of grx5Δ cells, arguing against lengthy mechanisms such as autophagic delivery of ribosomes to the vacuole (17) or induction of the apoptotic program (14). Northern hybridizations with probes for other RNA types revealed increased degradation of 5S rRNA, 5.8S rRNA, and tRNAs after treatment of grx5Δ cells with menadione or H2O2 (Fig. S2, C–F). However, large rRNAs (18S and 25S) were by far the most severely affected RNA species (Fig. S2, A and B), with only ∼2% of intact 25S rRNA remaining after 2-h treatment with 50 μm menadione (Fig. S2A). Hybridizations with additional 25S rRNA probes verified extensive degradation of the entire rRNA molecule in oxidant-treated grx5Δ cells (Fig. S3).

Figure 2.

25S rRNA fragmentation occurs rapidly in grx5Δ cells in response to oxidant treatment. A, RNA was sampled from mid-log cultures treated with 50 μm menadione (K3) for the indicated times. The full-length 25S rRNA and the ES7-cleaved fragment were detected by Northern hybridization using probe y540. B, change in relative levels of the full-length 25S rRNA and 5′ ES7-cleaved fragment over time. The phosphorimaging signals of the RNA bands in A were fit to a one-phase decay/growth model.

Collectively, these data show that Grx5 plays a crucial role in maintaining ribosome integrity during oxidative stress. Lack of Grx5 greatly intensifies the effects of oxidants on ribosomes. This not only increases the number of ES7-cleaved ribosomes, but can also lead to runaway ribosome degradation after treatment with low oxidant levels that are survivable in Grx5-expressing cells.

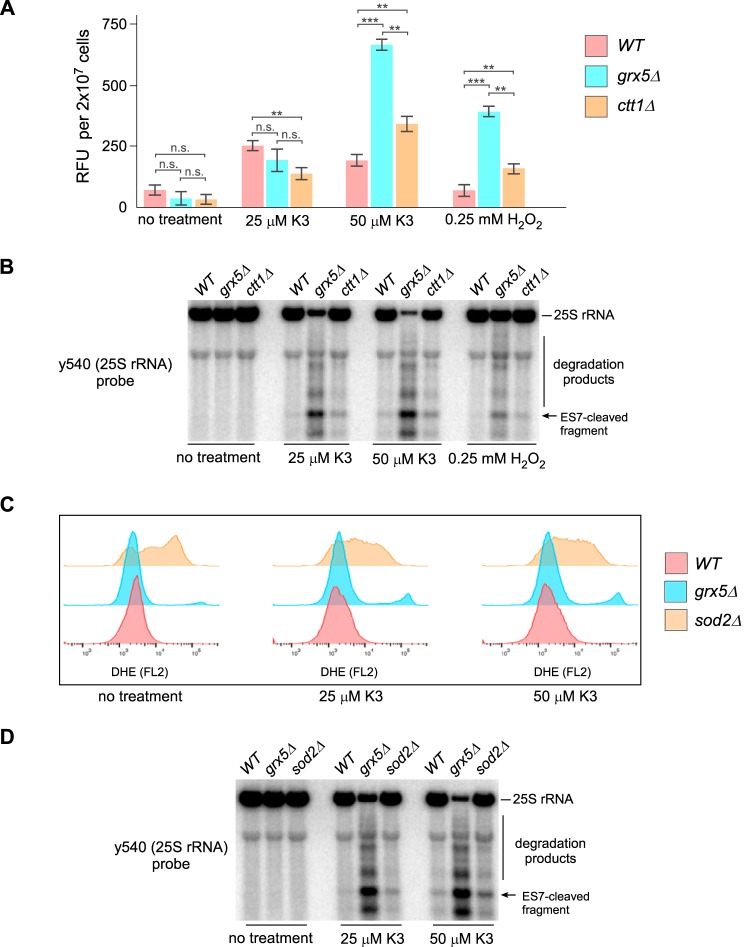

The increase in intracellular ROS levels is not sufficient to explain the ribosome degradation phenotype in grx5Δ cells

Grx5 belongs to the glutaredoxin family of enzymes, also known as GSH-dependent oxidoreductases, many of which help to maintain the redox state of proteins during oxidative stress (18). Because some glutaredoxins can also function as ROS scavengers (19, 20), we first sought to determine how lack of Grx5 affected the cellular ROS load. We estimated H2O2 levels in grx5Δ cells by using for comparison a ctt1Δ strain deficient for catalase, a key H2O2-inactivating enzyme. Amplex Red assays performed after treatment with 50 μm menadione or 0.25 mm H2O2 indeed revealed elevated H2O2 levels in grx5Δ cells as well as in the control ctt1Δ strain (Fig. 3A). However, the observed increases in H2O2 did not correlate well with the extent of rRNA degradation (Fig. 3B). For instance, grx5Δ cells exhibited more rRNA degradation after treatment with 25 μm menadione than the WT and ctt1Δ cells after 50 μm treatment (Fig. 3B) despite the lack of a comparable H2O2 increase (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Lack of direct correlation between ROS levels and the extent of 25S rRNA fragmentation. A, relative amounts of intracellular H2O2 as determined by an Amplex Red assay. Mid-log WT, grx5Δ, and ctt1Δ cells grown in YPDA were treated with 25 or 50 μm menadione (K3) for 2 h, 0.25 mm H2O2 for 30 min, or remained untreated. Data show mean relative fluorescence units (RFU) in three technical replicates; error bars represent S.D. Two-tailed Student's t test was used for statistical analysis. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. B, Northern hybridization analysis of 25S rRNA fragmentation from the same cultures as in A. SYBR Gold staining of the gel is shown in Fig. S4A. The experiment shown in A and B was performed twice with similar results. C, analysis of superoxide levels in WT, grx5Δ, and sod2Δ strains treated with menadione as above. Cells were stained with DHE and analyzed by flow cytometry using FlowJo software. D, Northern hybridization analysis of 25S rRNA fragmentation from the same cultures as in C. SYBR Gold staining of the gel is shown in Fig. S4B.

To assess the levels of the O2˙̄ radical in oxidant-treated grx5Δ cells, we used the superoxide-specific probe dihydroethidium (DHE) (21). Oxidized DHE was analyzed by a flow cytometry assay, which revealed moderately increased superoxide levels in grx5Δ cells compared with the WT cells (Fig. 3C). However, the O2˙̄ levels detected in grx5Δ cells were less pronounced than in the control sod2Δ strain lacking superoxide dismutase (Fig. 3C). Importantly, sod2Δ cells displayed significantly lower rRNA degradation than similarly treated grx5Δ cells (Fig. 3D). Thus, neither hydrogen peroxide nor superoxide radical levels reflect the severity of ribosome degradation during oxidant treatments of grx5Δ cells, suggesting that additional factor(s) may play a role in this process.

Increased levels of labile iron is a key factor in 25S rRNA degradation in grx5Δ cells

Previous studies have shown that Grx5 participates in iron–sulfur cluster (ISC) protein biogenesis (22–27), whereas the lack of Grx5 function causes iron accumulation in yeast cells (25, 28). Iron can both potentiate ROS production and exacerbate ROS-induced toxicity in the cell (28, 29). We therefore asked whether the disruption of iron homeostasis in grx5Δ cells contributes to the oxidant-induced effects on rRNA.

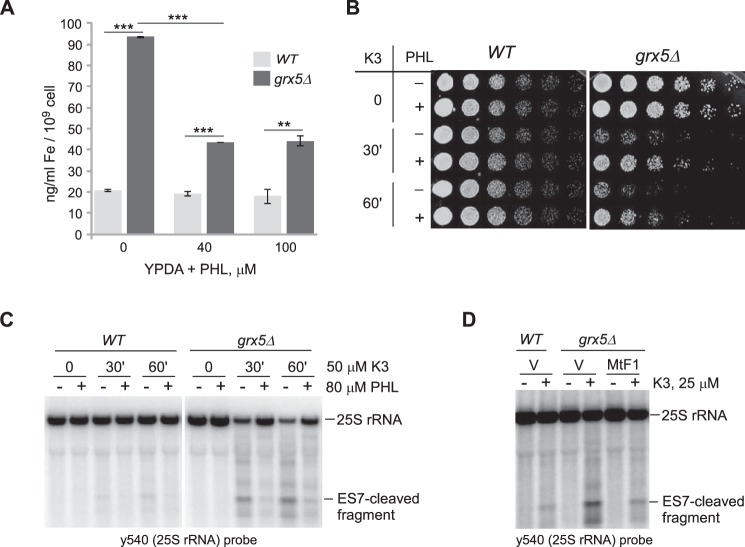

First, we analyzed the iron content of the grx5Δ cells and confirmed that it was significantly increased compared with the WT (Fig. 4A), in agreement with the results of a previous study (25). We also found that treatment of grx5Δ cells with the membrane permeable Fe2+ chelator 1,2-phenanthroline (PHL) (30) lowers the extent of the iron excess caused by Grx5 deficiency (Fig. 4A). We then assayed the viability of the WT and grx5Δ cells after short treatment (30 and 60 min) with 50 μm menadione in the presence or absence of PHL. This dose of menadione did not reduce survival in WT cells (Fig. 4B, left) but severely affected the viability of grx5Δ cells (Fig. 4B, right), consistent with the reported hypersensitivity of Grx5-deficient cells to oxidants (Fig. 1D and Ref. 16). Remarkably, the addition of PHL prior to menadione treatment alleviated the oxidant-induced loss of viability in grx5Δ cells (Fig. 4B, right). Analysis of RNA extracted from these cells showed protection of 25S rRNA from menadione-induced degradation by PHL (Fig. 4C and S5A). Similar protective effects of PHL were observed with H2O2 treatments (Fig. S5).

Figure 4.

Iron overload contributes to oxidant sensitivity and the degradation of ribosomes in grx5Δ cells. A, the intracellular iron level is increased in grx5Δ cells. Overnight cultures were diluted with YPDA to A600 ∼0.2, grown for 4 h, and treated or not with PHL for 1 h. Data show mean values in three biological replicates; error bars represent S.D. Two-tailed Student's t test was used for statistical analysis. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. B, PHL restores viability in menadione-treated grx5Δ cells. Cultures grown as in A were treated with 50 μm menadione for 30 or 60 min. Where indicated, cultures were pretreated with 80 μm PHL for 30 min prior to oxidant addition. After treatments, cells were washed, and 2 × 106 cells were serially diluted (1:5) and plated on YPDA agar plates. The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 2 days (WT) or 3 days (grx5Δ). C, PHL pretreatment suppresses the 25S rRNA degradation phenotype. RNA was extracted from the cultures shown in B and analyzed by Northern hybridization with probe y540. SYBR Gold staining of the gel is shown in Fig. S4C. D, suppression of rRNA degradation by ferritin expression. Cells transformed with an empty vector (V) or a mammalian ferritin expression construct (MtF1) were treated or not with 25 μm menadione for 2 h. RNA was analyzed as in C. SYBR Gold staining of the gel is shown in Fig. S4D.

To address the contribution of iron through an independent approach, we used overexpression of the human ferritin MtF1 to decrease the labile intracellular iron pool in grx5Δ cells. Human ferritins maintain proper iron homeostasis by sequestering excess iron in intracellular complexes (31). Expression of the human mitochondrial ferritin MtF1 has been shown previously to effectively reduce free iron concentration in yeast cells (32). Consistent with the results obtained via chemical chelation of iron, grx5Δ cells harboring the MtF1 expression construct displayed reduced degradation of 25S rRNA after oxidant treatment compared with cells transformed with an empty vector plasmid (Fig. 4D).

Based on these data, we conclude that the extent of oxidant-induced rRNA cleavages depends on intracellular iron levels. A defect in iron homeostasis, which leads to accumulation of excessive iron in cells deficient for Grx5 function, may thus explain why severe RNA damage is observed in grx5Δ cells but not in strains defective for various ROS-scavenging enzymes (Fig. 1C).

Iron-dependent site-specific cleavage of 25S rRNA in vitro

The above results indicate that the severe degradation of ribosomes in grx5Δ cells results from the combination of two factors: oxidants and high intracellular iron. Transition metal ions, including iron, can enhance ROS-induced damage in biomolecules, at least in part, through the generation of the highly reactive ·OH radicals in a Fenton reaction:

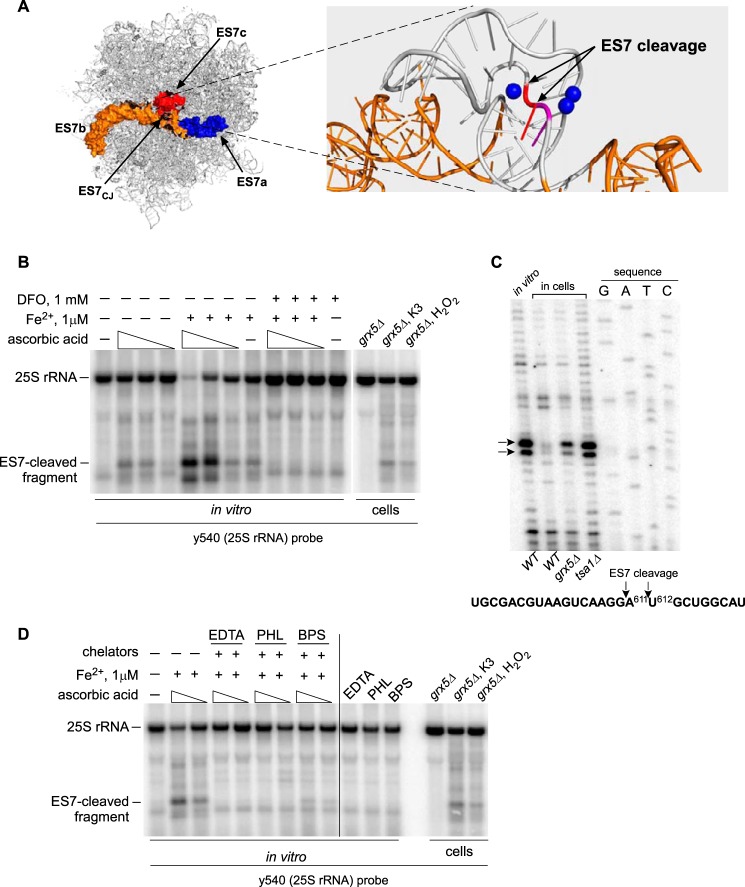

This led us consider the possibility that the rRNA cleavages might be a result of chemical rather than enzymatic hydrolysis. These cleavages might be directed by redox-reactive iron bound at specific ribosomal sites; for example, through interactions with rRNA or ribosomal proteins in the proximity of the RNA backbone. Previous studies have shown that binding of redox-active metals to remove DNA and RNA molecules can give rise to oxidizing species that are not freely diffusible, thereby producing site-specific cleavages (33–36). Studies have also shown that Fe2+ can substitute for Mg2+ in RNA (37), with highly structured RNA often exhibiting preferred sites for Fe2+ binding (33). Examination of the ES7 region in yeast 25S rRNA, where the major iron-dependent cleavage takes place, revealed three Mg2+ ions located 6–8 Å away from the ES7 cleavage site (Fig. 5A), providing potential sites for exchange with Fe2+ ions.

Figure 5.

25S rRNA undergoes iron-mediated ES7 cleavage in vitro. A, left panel, ribosomal location of the yeast ES7 expansion segment, with surface representation of the a, b, and c arms of 25S rRNA in blue, orange, and red, respectively. ES7CJ is the tripartite junction region. Right panel, enlarged image of the junction, with ES7c in gray and ES7a-b in orange. Nucleotides A611 and U612 at the cleavage site are shown in red and magenta, respectively. Mg2+ ions in the vicinity to the cleavage site are shown as blue spheres. B, left, in vitro cleavage of purified ribosomes with 500, 50, or 5 μm ascorbic acid. Where indicated, reactions contained 1 μm Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2. To chelate iron, ribosomes were pretreated with 1 mm DFO. Reaction products were analyzed by Northern blotting with probe y540. Right, rRNA from grx5Δ cells left untreated or treated with 50 μm menadione or 0.25 mm H2O2 was loaded for comparison on the same gel. C, primer extension analysis of the ES7 region in 25S rRNA after in vitro cleavage with 50 μm ascorbic acid and 1 μm Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2. Control RNAs were extracted from WT cells, grx5Δ cells treated with 50 μm menadione, and tsa1Δ cells treated with 20 mm DTT. Primer extensions were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide/urea gel next to a sequencing ladder. D, ribosomes were treated with 50 or 500 μm ascorbic acid in the presence of 1 μm Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 in the absence (−) or presence of 100 μm metal chelators EDTA, PHL or BPS. RNA was analyzed as described in B.

To test the hypothesis that the site-specific rRNA cleavages in vivo may be driven by redox-active iron bound to ribosomes, we sought to reconstitute the cleavage process in vitro. We devised reaction conditions based on earlier studies showing that ascorbic acid can induce localized redox reactions at the sites of metal binding (38, 39). Cleavage of nucleic acids by ascorbate in the presence of molecular oxygen is thought to occur by a multistage mechanism involving metal-catalyzed oxidation of ascorbic acid with molecular oxygen, leading to H2O2 formation (40) and reduction of the ligand-bound metal to the form capable of producing the highly reactive ·OH radicals from H2O2 (38):

We assembled the in vitro reactions with ribosomes that were purified from WT yeast cells using centrifugation through a sucrose cushion to remove soluble cytosolic components. To minimize the generation of hydroxyl radicals in solution, which can attack solvent-accessible regions of nucleic acids with little selectivity (41, 42), we did not add any exogenous H2O2, thus relying on ascorbate–iron redox cycling as the principal ROS source in the system. Fig. 5B shows the Northern blot analysis of 25S rRNA from ribosomes treated with varying concentrations of ascorbic acid and 1 μm Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2. The combination treatment efficiently induced ES7 cleavage, as evidenced by the accumulation of the ES7-cleaved fragment, and generated several additional minor bands on the gel that matched well the pattern of rRNA fragments appearing after oxidant treatment of grx5Δ cells (Fig. 5B). Primer extension analysis of the 25S rRNA from the ascorbic acid/iron-treated ribosomes (Fig. 5C) confirmed that the ES7 cleavage in vitro corresponds precisely to cleavage induced by redox stress in live cells, including grx5Δ cells and the previously studied thioredoxin peroxidase–deficient tsa1Δ cells (7).

One notable observation in these experiments was that ES7 cleavage could be obtained with ascorbic acid treatment alone (Fig. 5B), indicating that low levels of iron (or another redox-active metal) were already present in ribosomes isolated from cells. Supplementing the ribosome cleavage reaction with Fe2+ markedly increased the level of the ES7 cleavage product (Fig. 5B), showing that iron can indeed promote cleavage at this site. Conversely, addition of the iron chelator deferoxamine (DFO) completely blocked rRNA cleavage (Fig. 5B). Similar protective effects were observed with other chelating agents (EDTA, PHL, and BPS; Fig. 5D), consistent with their ability to displace iron from complexes with biomolecules. Because soluble Fe(EDTA) complexes can readily react with H2O2 and generate diffusible ·OH radicals (43, 44), this result further supports the idea that the site specificity of rRNA cleavages depends on the iron ion association with rRNA.

Discussion

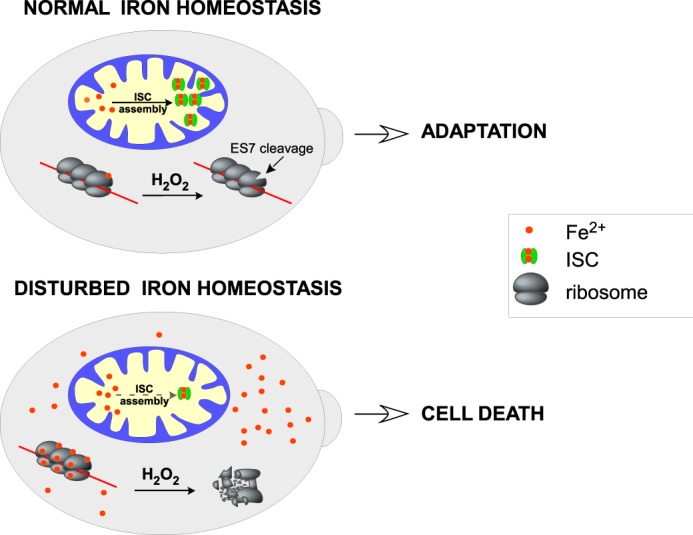

Site-specific cleavages of rRNA have been observed previously in different organisms that experience various types of stress (12–14, 45–47). Although these cleavages were ascribed to cellular nucleases, in most cases the enzymes responsible for initiating rRNA strand breaks were not conclusively identified. The results presented here provide several lines of evidence that rRNA cleavages associated with oxidative stress in yeast cells can occur through a nonenzymatic mechanism based on rRNA strand scission by redox-active iron bound to the ribosome. These findings implicate intracellular iron as a key determinant of the effects of oxidative stress on ribosomes (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

A working model of the dual role of iron in ribosomes. In cells with balanced iron metabolism, ROS cause limited, position-specific cleavages in rRNA at the sites of bound iron. This might affect ribosome function and optimize translation to conditions of oxidative stress, potentially serving as a stress adaptation mechanism. Accumulation of labile iron, such as in cells with defects in mitochondrial iron metabolism, increases iron binding to ribosomes and leads to extensive rRNA fragmentation, causing global inhibition of translation, which, in turn, may accelerate cell death.

Iron is an essential nutrient that acts as a co-factor for many enzymes and transport proteins and participates in a wide variety of physiological processes, including respiration, DNA metabolism, lipid biosynthesis, oxygen transport, and others (48, 49). Eukaryotes have developed complex systems for iron uptake, utilization, and storage (48–50). Disruption of these systems can result in either iron shortage or overload, with mitochondrial defects often playing a major role in iron homeostasis disturbances (49). For example, defects in the mitochondrial ISC biosynthesis pathways can increase iron uptake, resulting in excessive amounts of iron in the cytoplasm (51). In this study, we found that deletion of the yeast mitochondrial monothiol glutaredoxin gene GRX5, involved in ISC biogenesis (22–27), made ribosomes highly susceptible to ROS-induced damage. This manifested in the extensive degradation of rRNA after exposure of cells to low-dose oxidants (Figs. 1, A–C, and 2 and Figs. S2 and S3) and was accompanied by a rapid decline in cell viability (Fig. 4B). Although grx5Δ cells contain elevated levels of ROS (Fig. 3, A and C), we observed no direct correlation between ROS amounts and the extent of rRNA fragmentation (Fig. 3, B and D). Instead, we found that lowering the iron content of grx5Δ cells through a cell-permeable chemical chelator or expression of the human mitochondrial ferritin MtF1 (32) suppressed cleavage formation in rRNA (Fig. 4, C and D, and Fig. S5) and improved cell survival (Fig. 4B).

Crucially, we found that probing ribosomes for the presence of bound metals using an in vitro ascorbic acid redox cycling reaction recapitulated the 25S rRNA cleavage pattern observed in cells. Supplementing this reaction with inorganic iron was sufficient to increase the efficiency of the ES7 rRNA cleavage, whereas iron chelation completely blocked it (Fig. 5, B and D). These data imply that no additional nuclease is required to cleave the rRNA. Consistent with a role of iron in generating rRNA strand breaks, we observed a markedly increased rRNA degradation during oxidative stress in grx5Δ and other mutants with excessive iron content but not in strains with defective ROS scavenging systems (Fig. 1C).3

One significant observation is that the iron-mediated rRNA cleavages both in vivo and in vitro were not random but rather site-specific. This argues for the existence of high-affinity iron binding sites within the ribosome structure. One possibility is that iron may be brought in proximity to the rRNA's sugar phosphate backbone by a protein capable of coordinating iron ions without inhibiting their redox potential. An alternative possibility is that rRNA itself captures iron ions; for instance, by substitution of Mg2+ in permissive and accessible rRNA structures. Consistent with this scenario, structural data demonstrate three Mg2+ ions inside of the ES7/ES7CJ region of 25S rRNA and located ∼6–8 Å away from the ES7 cleavage site (Fig. 5A). These Mg2+ ions are exposed to the solvent side of the large subunit, allowing their potential replacement with Fe2+. In support of iron binding by rRNA, previous studies have shown that Fe2+, being a divalent cation with similar ionic radii and geometric properties as Mg2+, is capable of structural and functional replacement of Mg2+ in nucleic acids (33, 37, 52–55). It is clear, however, that not every Mg2+ ion bound to the ribosome could be substituted by iron with the same efficiency. The number of Mg2+ ions estimated to exist in the ribosome structure by structural studies (8) greatly exceeds the number of rRNA cleavages observed after oxidant treatments (Fig. S2). The site specificity of iron binding to rRNA could depend on local structural features, by analogy to the previously described differential binding of iron to DNA (34). In addition, sequence- and structure-specific interactions of RNA with iron have been observed in iron-responsive elements within mRNAs (56), group I intron RNAs (33), and, recently, bacterial ribosomes (57).

The reaction between ligand-bound Fe2+ and H2O2 is capable of generating hydroxyl radicals (·OH) through a Fenton mechanism and higher oxidation states of iron, including highly reactive ferryl (Fe4+) species (44, 58). Similarly to ·OH, ferryl oxygen [Fe4+ = O]2+ is capable of nucleic acid strand cleavages, as seen with DNAzymes (59). The exact nature of the reactive species produced in a given reaction may depend on multiple factors, including pH, the nature of the substrate, and the chelation state of iron. Although discernible in a controlled chemical system, these parameters are often difficult to account for in a cellular setting (discussed in Ref. 44). Given the complex molecular environment of the ribosome, it is possible that different types of chemistry may underlie rRNA hydrolysis at specific ribosomal locations.

The function of iron as an effector for the ribosome in oxidative stress may be significant in different biological contexts. The finding that the ES7 rRNA cleavage occurs during adaptive stages of the oxidative stress response (7) suggests that iron-mediated rRNA cleavages are not purely destructive but may serve a beneficial biological function in healthy cells. For example, these cleavages might temporarily down-regulate protein synthesis or alter some specific aspects of ribosome function during oxidative stress. By contrast, a failure to control intracellular iron levels, such as seen in strains defective in iron metabolism, predisposes ribosomes to rapid degradation even at low oxidant levels (Fig. 6). This may effectively prevent the synthesis of new proteins required for stress damage control and, hence, enforce a program of cellular self-destruction. In previous studies, ribosome degradation has been observed during apoptotic cell death (13, 14, 60). Recently, a form of programmed cell death in mammalian cells, termed ferroptosis (61), has been related to the induction of excessive lipid damage via iron-dependent peroxidation (reviewed in Ref. 62). Understanding the role of iron in ferroptosis is far from complete (48). It is possible that iron-dependent effects on the cell's ribosomes, analogous to those described here, may provide a convergence point for cell death mechanisms operating in diverse organisms.

Experimental procedures

Yeast media, chemicals, reagents, and treatment conditions

WT BY4742 (MATα his3–1 leu2–0 met15–0 ura3–0) and its derivative deletion strains (grx5Δ, sod1Δ, sod2Δ, ctt1Δ, cta1Δ, and tsa1Δ) were obtained from Thermo Fisher. New grx5Δ strains were generated by mating BY4741 (MATa his3–1 leu2–0 met15–0 ura3–0) with grx5Δ, followed by subsequent tetrad dissection as described previously (63). A ρ0 strain (MATa leu2–3, 112 trp1–1 can1–100 ura3–1 ade2–1 his3–11,15 [phi+]) was kindly provided by Randy Strich.

We used standard recipes for YPDA (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose, and 10 mg/l adenine), YPAc (1% KOAc, 2% peptone, and 1% yeast extract), and synthetic drop-out media. Unless indicated otherwise, overnight yeast cultures were diluted with fresh YPDA to A600 ∼ 0.2 and grown for an additional 4 h at 30 °C before each experiment.

Cells were treated with H2O2 (Avantor Performance Materials), menadione (Enzo), and PHL (VWR Life Science). For in vitro reactions, we used Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 (Sigma), ascorbic acid (Alfa Aesar), DFO (BioVision), 4,7-diphenyl-1,10-phenanthrolinedisulfonic acid (BPS, Alfa Aesar), and EDTA (Sigma).

The human mitochondrial ferritin gene MTF1 was cloned from human complementary DNA into the pNS6 vector using standard PCR-based techniques. The pNS6 vector was created by replacing the GAL1-GAL10 promoter region within PESC-his (Stratagene) with a 1.5-kb ADH1 promoter region from the PUAD plasmid (a kind gift from Randy Strich) (64).

RNA extraction, Northern blotting, and primer extension

Total RNA was isolated from cells using one-step extraction with formamide–EDTA as described previously (15). To analyze large rRNA species (25S and 18S rRNAs), RNA was separated on 1.2% agarose gels containing 1.3% formaldehyde (65). Small rRNAs and tRNAs were separated on 8% polyacrylamide gels containing 8 m urea as described previously (66). To visualize total RNA, agarose gels were stained with SYBR Gold (Invitrogen) at room temperature for 30 min, and the fluorescent signal was scanned using a Typhoon 9200 imager (GE Healthcare) at 532 nm. RNA was transferred to nylon membranes (Hybond N, GE Biosciences), and individual rRNA and tRNA species were visualized by Northern hybridizations using 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probes (67). The sequences of all probes used in this study are presented in Table S1. All hybridizations were analyzed using Typhoon 9200 in phosphorimaging mode and ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare). For quantification, the volume of the hybridization signal corresponding to the fragment(s) of interest was converted to phosphorimaging units, and the average image background value was subtracted. For primer extensions, a total of 3 μg of RNA was separated on a guanidine thiocyanate–containing gel, and rRNA was extracted from excised bands as described previously (68). RNA was annealed with 2 pmol of the 32P-labeled primer Prex1 and used for primer extensions (69). The Prex1 probe sequence can be found in Table S1. Reaction products were processed and analyzed on a 6% polyacrylamide/urea gel (7). Sequencing reactions were performed with SequiTherm EXCEL II (Epicenter) using 250 ng of the pJD694 plasmid containing rDNA (70) as a template and the Prex1 primer.

ROS detection

To measure H2O2 levels, Amplex Red assays were performed with a kit from Thermo Fisher as described previously (7) with a few minor modifications. Briefly, 2 × 107 mid-log phase cells were collected, washed with PBS, and resuspended in 300 μl of the reaction buffer supplied with the kit. Cells were incubated for 30 min in a 30 °C shaker and centrifuged, and 50 μl of supernatant was taken into an Amplex Red assay reaction performed in triplicate. The fluorescence of the reaction product resorufin was measured at 590 nm using a Synergy HT microplate reader (BioTek).

For analysis of the mitochondrial superoxide, we used a technique described previously (71). Briefly, 2 × 107 cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 500 μl of PBS, and stained with 2.5 μg/ml DHE (Molecular Probes) for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. Fluorescence was measured using a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer (excitation at 488 nm, emission at 585/40 nm), and histograms were analyzed in FlowJo version 10.

Measurement of iron levels

To determine levels of total cellular iron, we used a technique described previously (72). Briefly, cells were collected and counted, and the same amounts of cells (5 × 108) were washed and resuspended in 3% nitric acid. Cells were incubated for 16 h at 98 °C, followed by iron chelation with BPS. The absorbance was measured at 535 nm (73).

Ribosome isolation

Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed, and lysed by glass bead shearing in 30 mm HEPES–NaOH (pH 7.4), 100 mm KOAc, 3 mm MgOAc, 200 μg/ml heparin, and 100 μm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation, and the amount corresponding to 50–100 A260 units was loaded onto 500 μl of 50% (w/v) sucrose cushion prepared in 70 mm NH4Cl, 4 mm MgCl2, and 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). Lysates were centrifuged at 55,000 rpm at 4 °C for 1 h 20 min in a TLA-55 rotor (Beckman). Ribosomal pellets were washed with buffer K (20 mm HEPES–NaOH (pH 7.4), 40 mm KCl, and 4 mm MgCl2) and frozen at −80 °C.

In vitro redox cycling reaction

Pellets of purified ribosomes (see above) were resuspended in 100 μl of buffer K supplemented with RNaselock (Thermo Fisher). The RNA concentration was estimated spectrophotometrically, and 5 μg was used for one reaction. The reaction volume was adjusted to 100 μl with buffer K. Solutions of ascorbic acid, Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2, DFO, PHL, BPS, and EDTA were freshly prepared as 100× stocks. 1 μl of each reaction component was placed on a tube wall, and the tubes were briefly centrifuged to start all reactions simultaneously and incubated on ice for 10 min. The reactions were stopped with 50 μl of 0.1 m thiourea. RNA was precipitated by isopropanol, washed with 80% ethanol, and dissolved in 6 μl of FAE (98% formamide and 10 mm EDTA) (15). Reaction products were resolved on agarose gels and analyzed by Northern hybridizations as described above.

Structural analysis

PDB file 4V88 (8) was obtained from the Protein Data Bank and visualized with PyMOL 2.1 (Schrödinger).

Cell viability and growth assays

For growth assays, yeast cultures were adjusted to A600 ∼0.1 with appropriate media (with or without 50 μm menadione), 200 μl/well was inoculated into 96-well plates in three replicates, and the cultures were grown for 36 h at 30 °C with shaking. A600 measurements were taken every 5 min and automatically recorded using a BioTek Synergy HT microplate reader.

For viability assays, overnight cultures were diluted with YPDA to A600 ∼0.2, grown for 4 h, and incubated with 80 μm PHL for 1 h or left untreated. For oxidant treatment, cells were incubated with 50 μm menadione for 30 min to 1 h at 30 °C with shaking. Cells were washed, resuspended in fresh YPDA, and adjusted to the same concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml. Six 1:5 serial dilutions for each culture were plated on YPDA agar plates and incubated at 30 °C for 3–5 days.

Author contributions

D. G. P., and N. S. conceptualization; J. A. Z., A. G., B. M. T., and N. S. data curation; J. A. Z., A. G., and D. G. P. software; J. A. Z., A. G., D. S., D. G. P., and N. S. formal analysis; N. S. funding acquisition; J. A. Z., A. G., B. M. T., D. S., D. G. P., and N. S. investigation; B. M. T., A. G., D. G. P., and N. S. methodology; D. G. P. resources; D. G. P. and N. S. writing-review and editing; N. S. supervision; D. G. P and N. S. validation; N. S. writing-original draft; N. S. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Randy Strich, Katrina Cooper, and the members of their laboratories for critical evaluation of this work. We also thank Russell Sapio for help with cloning of the mammalian ferritin gene and constructive comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM114308 (to N. S.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S5 and Table S1.

J. A. Zinskie, A. Ghosh, B. M. Trainor, D. Shedlovskiy, D. G. Pestov, and N. Shcherbik, unpublished results.

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- DHE

- dihydroethidium

- ISC

- iron–sulfur cluster

- PHL

- 1,2-phenanthroline

- DFO

- deferoxamine

- BPS

- 4,7-diphenyl-1,10-phenanthrolinedisulfonic acid.

References

- 1. D'Autréaux B., and Toledano M. B. (2007) ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 813–824 10.1038/nrm2256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marinho H. S., Real C., Cyrne L., Soares H., and Antunes F. (2014) Hydrogen peroxide sensing, signaling and regulation of transcription factors. Redox Biol. 2, 535–562 10.1016/j.redox.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Willi J., Küpfer P., Evéquoz D., Fernandez G., Katz A., Leumann C., and Polacek N. (2018) Oxidative stress damages rRNA inside the ribosome and differentially affects the catalytic center. Nucleic Acids Res. 10.1093/nar/gkx1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Topf U., Suppanz I., Samluk L., Wrobel L., Böser A., Sakowska P., Knapp B., Pietrzyk M. K., Chacinska A., and Warscheid B. (2018) Quantitative proteomics identifies redox switches for global translation modulation by mitochondrially produced reactive oxygen species. Nat. Commun. 9, 324 10.1038/s41467-017-02694-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ding Q., Markesbery W. R., Cecarini V., and Keller J. N. (2006) Decreased RNA, and increased RNA oxidation, in ribosomes from early Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem. Res. 31, 705–710 10.1007/s11064-006-9071-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Honda K., Smith M. A., Zhu X., Baus D., Merrick W. C., Tartakoff A. M., Hattier T., Harris P. L., Siedlak S. L., Fujioka H., Liu Q., Moreira P. I., Miller F. P., Nunomura A., Shimohama S., and Perry G. (2005) Ribosomal RNA in Alzheimer disease is oxidized by bound redox-active iron. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 20978–20986 10.1074/jbc.M500526200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shedlovskiy D., Zinskie J. A., Gardner E., Pestov D. G., and Shcherbik N. (2017) Endonucleolytic cleavage in the expansion segment 7 of 25S rRNA is an early marker of low-level oxidative stress in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 18469–18485 10.1074/jbc.M117.800003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ben-Shem A., Garreau de Loubresse N., Melnikov S., Jenner L., Yusupova G., and Yusupov M. (2011) The structure of the eukaryotic ribosome at 3.0 Å resolution. Science 334, 1524–1529 10.1126/science.1212642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Melnikov S., Ben-Shem A., Garreau de Loubresse N., Jenner L., Yusupova G., and Yusupov M. (2012) One core, two shells: bacterial and eukaryotic ribosomes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 560–567 10.1038/nsmb.2313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perrone G. G., Tan S.-X., and Dawes I. W. (2008) Reactive oxygen species and yeast apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783, 1354–1368 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simon H. U., Haj-Yehia A., and Levi-Schaffer F. (2000) Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis 5, 415–418 10.1023/A:1009616228304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Erental A., Kalderon Z., Saada A., Smith Y., and Engelberg-Kulka H. (2014) Apoptosis-like death, an extreme SOS response in Escherichia coli. mBio. 5, e01426–01414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Houge G., Døskeland S. O., Bøe R., and Lanotte M. (1993) Selective cleavage of 28S rRNA variable regions V3 and V13 in myeloid leukemia cell apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 315, 16–20 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81123-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mroczek S., and Kufel J. (2008) Apoptotic signals induce specific degradation of ribosomal RNA in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2874–2888 10.1093/nar/gkm1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shedlovskiy D., Shcherbik N., and Pestov D. G. (2017) One-step hot formamide extraction of RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA Biol. 14, 1722–1726 10.1080/15476286.2017.1345417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rodríguez-Manzaneque M. T., Ros J., Cabiscol E., Sorribas A., and Herrero E. (1999) Grx5 glutaredoxin plays a central role in protection against protein oxidative damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 8180–8190 10.1128/MCB.19.12.8180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang H., Kawamata T., Horie T., Tsugawa H., Nakayama Y., Ohsumi Y., and Fukusaki E. (2015) Bulk RNA degradation by nitrogen starvation-induced autophagy in yeast. EMBO J. 34, 154–168 10.15252/embj.201489083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fernandes A. P., and Holmgren A. (2004) Glutaredoxins: glutathione-dependent redox enzymes with functions far beyond a simple thioredoxin backup system. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 6, 63–74 10.1089/152308604771978354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen X., Lv Q., Hong Y., Chen X., Cheng B., and Wu T. (2017) IL-1β maintains the redox balance by regulating glutaredoxin 1 expression during oral carcinogenesis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 46, 332–339 10.1111/jop.12502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laporte D., Olate E., Salinas P., Salazar M., Jordana X., and Holuigue L. (2012) Glutaredoxin GRXS13 plays a key role in protection against photooxidative stress in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 503–515 10.1093/jxb/err301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dikalov S. I., and Harrison D. G. (2014) Methods for detection of mitochondrial and cellular reactive oxygen species. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 372–382 10.1089/ars.2012.4886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alves R., Herrero E., and Sorribas A. (2004) Predictive reconstruction of the mitochondrial iron-sulfur cluster assembly metabolism: II: role of glutaredoxin Grx5. Proteins 57, 481–492 10.1002/prot.20228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bellí G., Polaina J., Tamarit J., De La Torre M. A., Rodríguez-Manzaneque M. T., Ros J., and Herrero E. (2002) Structure-function analysis of yeast Grx5 monothiol glutaredoxin defines essential amino acids for the function of the protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37590–37596 10.1074/jbc.M201688200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mühlenhoff U., Gerber J., Richhardt N., and Lill R. (2003) Components involved in assembly and dislocation of iron-sulfur clusters on the scaffold protein Isu1p. EMBO J. 22, 4815–4825 10.1093/emboj/cdg446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rodríguez-Manzaneque M. T., Tamarit J., Bellí G., Ros J., and Herrero E. (2002) Grx5 is a mitochondrial glutaredoxin required for the activity of iron/sulfur enzymes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13, 1109–1121 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tamarit J., Belli G., Cabiscol E., Herrero E., and Ros J. (2003) Biochemical characterization of yeast mitochondrial Grx5 monothiol glutaredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25745–25751 10.1074/jbc.M303477200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vilella F., Alves R., Rodríguez-Manzaneque M. T., Bellí G., Swaminathan S., Sunnerhagen P., and Herrero E. (2004) Evolution and cellular function of monothiol glutaredoxins: involvement in iron-sulphur cluster assembly. Comp. Funct. Genomics. 5, 328–341 10.1002/cfg.406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gomez M., Pérez-Gallardo R. V., Sánchez L. A., Díaz-Pérez A. L., Cortés-Rojo C., Meza Carmen V., Saavedra-Molina A., Lara-Romero J., Jiménez-Sandoval S., Rodríguez F., Rodríguez-Zavala J. S., and Campos-García J. (2014) Malfunctioning of the iron-sulfur cluster assembly machinery in Saccharomyces cerevisiae produces oxidative stress via an iron-dependent mechanism, causing dysfunction in respiratory complexes. PLoS ONE 9, e111585 10.1371/journal.pone.0111585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mahaseth T., and Kuzminov A. (2017) Potentiation of hydrogen peroxide toxicity: from catalase inhibition to stable DNA-iron complexes. Mutat. Res. 773, 274–281 10.1016/j.mrrev.2016.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee T. S., Kolthoff I. M., and Leussing D. L. (1948) Reaction of ferrous and ferric ions with 1,10-phenanthroline; kinetics of formation and dissociation of ferrous phenanthroline. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 70, 3596–3600 10.1021/ja01191a015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cazzola M., Invernizzi R., Bergamaschi G., Levi S., Corsi B., Travaglino E., Rolandi V., Biasiotto G., Drysdale J., and Arosio P. (2003) Mitochondrial ferritin expression in erythroid cells from patients with sideroblastic anemia. Blood 101, 1996–2000 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Campanella A., Isaya G., O'Neill H. A., Santambrogio P., Cozzi A., Arosio P., and Levi S. (2004) The expression of human mitochondrial ferritin rescues respiratory function in frataxin-deficient yeast. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13, 2279–2288 10.1093/hmg/ddh232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Berens C., Streicher B., Schroeder R., and Hillen W. (1998) Visualizing metal-ion-binding sites in group I introns by iron(II)-mediated Fenton reactions. Chem. Biol. 5, 163–175 10.1016/S1074-5521(98)90061-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Henle E. S., Han Z., Tang N., Rai P., Luo Y., and Linn S. (1999) Sequence-specific DNA cleavage by Fe2+-mediated Fenton reactions has possible biological implications. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 962–971 10.1074/jbc.274.2.962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oikawa S., and Kawanishi S. (1998) Distinct mechanisms of site-specific DNA damage induced by endogenous reductants in the presence of iron(III) and copper(II). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1399, 19–30 10.1016/S0167-4781(98)00092-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang Y., and Van Ness B. (1989) Site-specific cleavage of supercoiled DNA by ascorbate/Cu(II). Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 6915–6926 10.1093/nar/17.17.6915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Athavale S. S., Petrov A. S., Hsiao C., Watkins D., Prickett C. D., Gossett J. J., Lie L., Bowman J. C., O'Neill E., Bernier C. R., Hud N. V., Wartell R. M., Harvey S. C., and Williams L. D. (2012) RNA folding and catalysis mediated by iron (II). PLoS ONE 7, e38024 10.1371/journal.pone.0038024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morgan A. R., Cone R. L., and Elgert T. M. (1976) The mechanism of DNA strand breakage by vitamin C and superoxide and the protective roles of catalase and superoxide dismutase. Nucleic Acids Res. 3, 1139–1149 10.1093/nar/3.5.1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Samuni A., Aronovitch J., Godinger D., Chevion M., and Czapski G. (1983) On the cytotoxicity of vitamin C and metal ions: a site-specific Fenton mechanism. Eur. J. Biochem. 137, 119–124 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07804.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Khan M. M., and Martell A. E. (1967) Metal ion and metal chelate catalyzed oxidation of ascorbic acid by molecular oxygen: I: cupric and ferric ion catalyzed oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 89, 4176–4185 10.1021/ja00992a036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Latham J. A., and Cech T. R. (1989) Defining the inside and outside of a catalytic RNA molecule. Science 245, 276–282 10.1126/science.2501870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tullius T. D., and Dombroski B. A. (1986) Hydroxyl radical “footprinting”: high-resolution information about DNA-protein contacts and application to λ repressor and Cro protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 83, 5469–5473 10.1073/pnas.83.15.5469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Graf E., Mahoney J. R., Bryant R. G., and Eaton J. W. (1984) Iron-catalyzed hydroxyl radical formation: stringent requirement for free iron coordination site. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 3620–3624 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Winterbourn C. C. (1995) Toxicity of iron and hydrogen peroxide: the Fenton reaction. Toxicol. Lett. 82–83, 969–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Deutscher M. P. (2009) Maturation and degradation of ribosomal RNA in bacteria. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 85, 369–391 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)00809-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Narendrula R., Mispel-Beyer K., Guo B., Parissenti A. M., Pritzker L. B., Pritzker K., Masilamani T., Wang X., and Lannér C. (2016) RNA disruption is associated with response to multiple classes of chemotherapy drugs in tumor cell lines. BMC Cancer 16, 146 10.1186/s12885-016-2197-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Padmanabhan P. K., Samant M., Cloutier S., Simard M. J., and Papadopoulou B. (2012) Apoptosis-like programmed cell death induces antisense ribosomal RNA (rRNA) fragmentation and rRNA degradation in Leishmania. Cell Death Differ. 19, 1972–1982 10.1038/cdd.2012.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bogdan A. R., Miyazawa M., Hashimoto K., and Tsuji Y. (2016) Regulators of iron homeostasis: new players in metabolism, cell death, and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 41, 274–286 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mühlenhoff U., Hoffmann B., Richter N., Rietzschel N., Spantgar F., Stehling O., Uzarska M. A., and Lill R. (2015) Compartmentalization of iron between mitochondria and the cytosol and its regulation. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 94, 292–308 10.1016/j.ejcb.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Martínez-Pastor M. T., Perea-García A., and Puig S. (2017) Mechanisms of iron sensing and regulation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 33, 75 10.1007/s11274-017-2215-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lill R., Srinivasan V., and Mühlenhoff U. (2014) The role of mitochondria in cytosolic-nuclear iron–sulfur protein biogenesis and in cellular iron regulation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 22, 111–119 10.1016/j.mib.2014.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Aguirre J. D., and Culotta V. C. (2012) Battles with iron: manganese in oxidative stress protection. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 13541–13548 10.1074/jbc.R111.312181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hsiao C., Chou I.-C., Okafor C. D., Bowman J. C., O'Neill E. B., Athavale S. S., Petrov A. S., Hud N. V., Wartell R. M., Harvey S. C., and Williams L. D. (2013) RNA with iron(II) as a cofactor catalyses electron transfer. Nat. Chem. 5, 525–528 10.1038/nchem.1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Okafor C. D., Lanier K. A., Petrov A. S., Athavale S. S., Bowman J. C., Hud N. V., and Williams L. D. (2017) Iron mediates catalysis of nucleic acid processing enzymes: support for Fe(II) as a cofactor before the great oxidation event. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 3634–3642 10.1093/nar/gkx171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Petrov A. S., Bowman J. C., Harvey S. C., and Williams L. D. (2011) Bidentate RNA-magnesium clamps: on the origin of the special role of magnesium in RNA folding. RNA 17, 291–297 10.1261/rna.2390311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ma J., Haldar S., Khan M. A., Sharma S. D., Merrick W. C., Theil E. C., and Goss D. J. (2012) Fe2+ binds iron responsive element-RNA, selectively changing protein-binding affinities and regulating mRNA repression and activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 8417–8422 10.1073/pnas.1120045109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bray M. S., Lenz T. K., Bowman J. C., Petrov A. S., Reddi A. R., Hud N. V., Williams L. D., and Glass J. B. (2018) Ferrous iron folds rRNA and mediates translation. bioRxiv 10.1101/256958 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Imlay J. A., Chin S. M., and Linn S. (1988) Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science 240, 640–642 10.1126/science.2834821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Stefan L., Denat F., and Monchaud D. (2012) Insights into how nucleotide supplements enhance the peroxidase-mimicking DNAzyme activity of the G-quadruplex/hemin system. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 8759–8772 10.1093/nar/gks581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. King K. L., Jewell C. M., Bortner C. D., and Cidlowski J. A. (2000) 28S ribosome degradation in lymphoid cell apoptosis: evidence for caspase and Bcl-2-dependent and -independent pathways. Cell Death Differ. 7, 994–1001 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Dixon S. J., Lemberg K. M., Lamprecht M. R., Skouta R., Zaitsev E. M., Gleason C. E., Patel D. N., Bauer A. J., Cantley A. M., Yang W. S., Morrison B. 3rd, and Stockwell B. R. (2012) Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149, 1060–1072 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Stockwell B. R., Friedmann Angeli J. P., Bayir H., Bush A. I., Conrad M., Dixon S. J., Fulda S., Gascón S., Hatzios S. K., Kagan V. E., Noel K., Jiang X., Linkermann A., Murphy M. E., Overholtzer M., et al. (2017) Ferroptosis: a regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell 171, 273–285 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kim S. J., and Strich R. (2016) Rpl22 is required for IME1 mRNA translation and meiotic induction in S. cerevisiae. Cell Div. 11, 10 10.1186/s13008-016-0024-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Shcherbik N. (2013) Golgi-mediated glycosylation determines residency of the T2 RNase Rny1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Traffic 14, 1209–1227 10.1111/tra.12122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mansour F. H., and Pestov D. G. (2013) Separation of long RNA by agarose-formaldehyde gel electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 441, 18–20 10.1016/j.ab.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Shcherbik N., Chernova T. A., Chernoff Y. O., and Pestov D. G. (2016) Distinct types of translation termination generate substrates for ribosome-associated quality control. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 6840–6852 10.1093/nar/gkw566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pestov D. G., Lapik Y. R., and Lau L. F. (2008) Assays for ribosomal RNA processing and ribosome assembly. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. Chapter 22, Unit 22.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wang M., Parshin A. V., Shcherbik N., and Pestov D. G. (2015) Reduced expression of the mouse ribosomal protein Rpl17 alters the diversity of mature ribosomes by enhancing production of shortened 5.8S rRNA. RNA 21, 1240–1248 10.1261/rna.051169.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kent T., Lapik Y. R., and Pestov D. G. (2009) The 5′ external transcribed spacer in mouse ribosomal RNA contains two cleavage sites. RNA 15, 14–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rakauskaite R., and Dinman J. D. (2006) An arc of unpaired “hinge bases” facilitates information exchange among functional centers of the ribosome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 8992–9002 10.1128/MCB.01311-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bonawitz N. D., Rodeheffer M. S., and Shadel G. S. (2006) Defective mitochondrial gene expression results in reactive oxygen species-mediated inhibition of respiration and reduction of yeast life span. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 4818–4829 10.1128/MCB.02360-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Almeida T., Marques M., Mojzita D., Amorim M. A., Silva R. D., Almeida B., Rodrigues P., Ludovico P., Hohmann S., Moradas-Ferreira P., Côrte-Real M., and Costa V. (2008) Isc1p plays a key role in hydrogen peroxide resistance and chronological lifespan through modulation of iron levels and apoptosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 19, 865–876 10.1091/mbc.e07-06-0604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tamarit J., Irazusta V., Moreno-Cermeño A., and Ros J. (2006) Colorimetric assay for the quantitation of iron in yeast. Anal. Biochem. 351, 149–151 10.1016/j.ab.2005.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.