Abstract

Toxoplasmosis is caused by an obligate intracellular parasite, the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii. Discovery of novel drugs against T. gondii infection could circumvent the toxicity of existing drugs and T. gondii resistance to current treatments. The autophagy-related protein 8 (Atg8)–Atg3 interaction in T. gondii is a promising drug target because of its importance for regulating Atg8 lipidation. We reported previously that TgAtg8 and TgAtg3 interact directly. Here we validated that substitutions of conserved residues of TgAtg8 interacting with the Atg8 family–interacting motif (AIM) in Atg3 disrupt the TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction and reduce TgAtg8 lipidation and autophagosome formation. These findings were consistent with results reported previously for Plasmodium Atg8, suggesting functional conservation of Atg8 in Toxoplasma and Plasmodium. Moreover, using peptide and AlphaScreen assays, we identified the AIM sequence in TgAtg3 that binds TgAtg8. We determined that the core TgAtg3 AIM contains a Phe239-Ala240-Asp241-Ile242 (239FADI242) signature distinct from the 105WLLP108 signature in the AIM of Plasmodium Atg3. Furthermore, an alanine-scanning assay revealed that the TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction in T. gondii also depends strongly on several residues surrounding the core TgAtg3 AIM, such as Asn238, Asp243, and Cys244. These results indicate that distinct AIMs in Atg3 contribute to differences between Toxoplasma and Plasmodium Atg8–Atg3 interactions. By elucidating critical residues involved in the TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction, our work paves the way for the discovery of potential anti-toxoplasmosis drugs. The quantitative and straightforward AlphaScreen assay developed here may enable high-throughput screening for small molecules disrupting the TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction.

Keywords: Toxoplasma gondii, autophagy, protein complex, protein domain, protein–protein interaction, AlphaScreen, Atg3, Atg8, Atg8 family–interacting motif, peptide assay

Introduction

Toxoplasmosis is caused by infection with the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii, an obligate intracellular parasite. This disease is a major public health burden in the developing world because of the resulting morbidity and mortality in humans and animals (1, 2). Existing treatments remain ineffective because of drug toxicity and failure to eliminate the parasite (3, 4). The identification of novel anti-toxoplasmosis drug targets is thus essential for future intervention strategies.

Autophagy is a catabolic process in eukaryotic cells that consists of the targeted degradation of cellular organelles along with their cytoplasm. The process is also important in cell growth, development, differentiation, and survival under stress in parasitic protozoa (5–8). Recent data obtained in Toxoplasma have shed light on a very important role for this machinery (9–11). The discovery of autophagy, an important aspect of programmed cell death in T. gondii, offers novel therapeutic opportunities to treat toxoplasmosis.

In macroautophagy, henceforth called autophagy, the autophagic cargos are sequestered by a double membrane structure called the autophagosome and degraded by fusion of the autophagosome with the lysosome or vacuole (12). Over 30 autophagy-related proteins (Atg) involved in autophagy have been identified in many eukaryotes, and two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems, the Atg8–phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)4 and Atg12–Atg5 systems, are required for formation of the autophagosome (13). Although the Atg12–Atg5 system is absent in T. gondii, the intact Atg8–PE conjugation system, including Atg3, Atg4, Atg7, and Atg8, has been identified (9, 14, 15). In the Atg8–PE system, Atg8 is an indispensable component of autophagosome formation and membrane expansion (16). Currently, there is only one Atg8 protein identified in yeast, whereas seven Atg8 homolog proteins have been found in human cells (17, 18). During formation of the autophagosome, these Atg8 family proteins are first proteolytically processed by Atg4 to expose a C-terminal glycine (19). In contrast, T. gondii Atg8 (TgAtg8) exists in an active form with a free C-terminal glycine (15). The exposed C terminus glycine of Atg8 is activated by Atg7, an E1-like activating enzyme, through a thioester bond to form an Atg8–Atg7 intermediate (20) and is then transferred to Atg3, an E2-like conjugating enzyme, to form another Atg8–Atg3 thioester intermediate (21) prior to being conjugated to PE in the phagophore membrane. In addition to forming the thioester intermediate with Atg3, Atg8 binds noncovalently to Atg3 before attaching the substrate (22).

In the Atg8–PE conjugation system, therefore, Atg8–Atg3 interaction is a key step. A crystal structural study of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Atg3 (ScAtg3) and its interaction with Atg8 showed that Atg3 specifically binds to Atg8 through an Atg8 family–interacting motif (AIM) sequence, WXXL, which is a short linear sequence that has been found in a growing number of proteins interacting with Atg8 homologs (22, 23). We showed previously that TgAtg8 is able to interact with TgAtg3 in vivo and in vitro, but the detailed interaction mechanism is unknown (24). To better understand the TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction in T. gondii, we set out to discover the potential AIM sequence in TgAtg3 that interacts with TgAtg8 by combining an overlapping peptide array with AlphaScreen assay technology. Furthermore, point mutants of TgAtg3 reveal the importance of each residue in the AIM sequence of TgAtg3 for the TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction. We demonstrate that TgAtg3 interacts directly with TgAtg8 through a conserved AIM sequence, 239FADI242. Collectively, these results establish the importance of these residues for the TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction, providing mechanistic insights into the TgAtg8–PE conjugation cascade in T. gondii.

Results

TgAtg8 possesses conserved structure and function

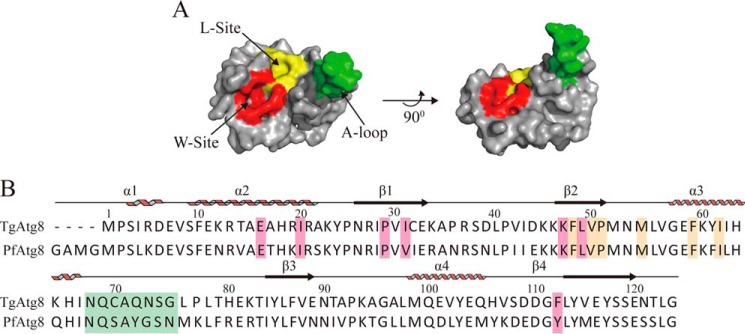

It has been reported that all Atg8 molecular structures from S. cerevisiae and its mammalian homologs possess three conserved regions: the N-terminal region, consisting of two tandem α-helical domains (α1 and α2); one exposed β strand (β2) and two hydrophobic pockets (W-site and L-site) near β2; and a C-terminal ubiquitin-like domain (23, 25). The W-site, consisting of Glu17, Ile21, Pro30, Ile32, Lys48, Leu50, and Phe104, is typically responsible for binding tryptophan in the AIM, whereas the L-site, consisting of Tyr49, Val51, Pro52, Leu55, Phe60, and Val63, is responsible for binding leucine in the AIM (26). In the case of Atg8, the β2 strand and two hydrophobic pockets, which are likewise identified in a protozoan Atg8 homolog (27, 28), are responsible for AIM binding (29). Recently, a unique A-loop region, which is conserved in Apicomplexa but absent in human Atg8 homologs, has been identified as another important structure for mediating the interaction between Atg8–Atg3 in Plasmodium (28).

To characterize the structure of TgAtg8, a sequence alignment and structural analysis of TgAtg8 and PfAtg8 were performed. Using the sequence and crystal structure of PfAtg8 (PDB code 4EOY) as a reference, the bioinformatics analysis revealed that TgAtg8 possesses a conserved molecular structure and sequences involved in the interaction with the AIM, such as the W-site, L-site, and A-loop (Fig. 1, A and B). Because of the high conservation of Atg8 in structure and sequence involved in the interaction with the AIM between Toxoplasma and Plasmodium, we mutated residues R27E, D44A/K45S/K46A, and deleted residues 68–76, which form the A-loop region, because they have been confirmed as key residues mediating the PfAtg8–PfAtg3 interaction (28).

Figure 1.

The structure and sequence of TgAtg8 is evolutionarily conserved with those of PfAtg8. A, predicted tertiary structure of TgAtg8, showing two hydrophobic pockets responsible for the recognition of Trp and Leu in the AIM (WXXL) motif, are the W-site (red) and L-site (yellow), and a unique A-loop structure (green). B, sequence alignment of TgAtg8. The secondary structural elements of TgAtg8 are shown above the alignment. Residues constituting the W-site, L-site, and A-loop are color-coded as in A. Residue numbers of TgAtg8 are shown above the alignment.

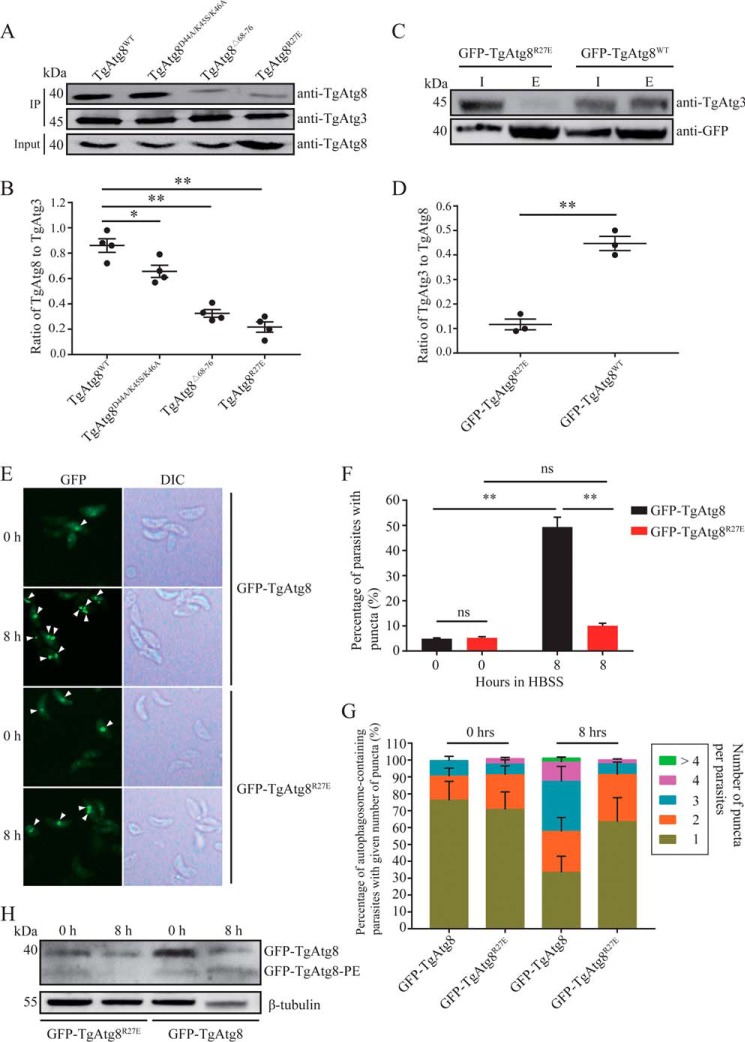

A pulldown assay with immobilized His6–TgAtg3 indicated that all three variants reduce the binding of TgAtg8 to His6–TgAtg3. In agreement with PfAtg8, the triple mutant TgAtg8D44A/K45S/K46A showed only a moderate decrease in binding, and both TgAtg8R27E and TgAtg8Δ68–76 binding showed the most remarkable decrease (Fig. 2, A and B). To test whether these residues of TgAtg8 are responsible for mediating the endogenous TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction in the tachyzoite stage, we examined the ability of TgAtg8R27E to bind to TgAtg3 using the GFP-TgAtg8R27E strain. Consistent with our in vitro pulldown assay, Western blotting using a specific anti-TgAtg3 antibody demonstrated that the amount of TgAtg3 binding to TgAtg8 was reduced significantly in the GFP-TgAtg8R27E strain compared with the GFP-TgAtg8 control (Fig. 2, C and D).

Figure 2.

Identification of TgAtg3-interacting residues in TgAtg8 and the impact of TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction on TgAtg8 lipidation and autophagosome formation. A, in vitro pulldown assay. His6–TgAtg3 was incubated with WT GST-TgAtg8 and GST-TgAtg8 mutants, followed by immobilization on an Ni-NTA column. Binding was assessed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Four independent experiments with a combination of in vivo immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blotting were performed. The image represents one of four independent experiments. B, binding was quantified with ImageJ as the ratio of bound TgAtg8 to TgAtg3. The mean values ± S.E. from four independent experiments are presented. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. C, in vivo immunoprecipitation using GFP antibodies. Protein extracts from either GFP-TgAtg8 cells or the GFP-TgAtg8R27E mutant were immunoprecipitated separately with anti-GFP beads. The input (I) and elution proteins (E) were analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Three independent experiments with a combination of in vivo immunoprecipitation and Western blotting were performed. The image represents one of three independent experiments. D, binding was quantified with ImageJ as the ratio of bound TgAtg3 to TgAtg8. The mean values ± S.E. from three independent experiments are presented. **, p < 0.01. E, extracellular tachyzoites were starved in HBSS medium for 8 h, and the GFP-TgAtg8 puncta were assessed using fluorescence microscopy. Puncta are indicated by white arrowheads. DIC, differential interference contrast. F, the proportions of parasites containing fluorescence-labeled TgAtg8-PE puncta from both GFP-TgAtg8 and GFP-TgAtg8R27E mutants. The mean values ± S.E. from three independent experiments are presented. **, p < 0.01; ns, not significant. G, the proportions of autophagosome-containing parasites with a given number of puncta from both GFP-TgAtg8 and GFP-TgAtg8R27E mutants. The mean values ± S.E. from three independent experiments are presented. H, protein lysates corresponding to tachyzoites incubated under the same starvation conditions as in E were separated by urea SDS-PAGE and analyzed with an anti-GFP antibody to detect TgAtg8 and the lipidated TgAtg8-PE form. Anti-β-tubulin was used as a loading control.

As mentioned above, the Atg8–Atg3 interaction has emerged as a crucial regulator of Atg8–PE autophagosome formation. We thus sought to measure the impact of the TgAtg8 variant on the formation of the TgAtg8 autophagosome by fluorescence microscopy on living tachyzoites. It has been verified that the number of parasites bearing GFP-labeled puncta increased quickly and reached a plateau after 8 h of starvation (15). Therefore, we carried out starvation experiments on either GFP-TgAtg8 or GFP-TgAtg8R27E extracellular tachyzoites for 8 h. In both strains, we found that the GFP-TgAtg8 signal is uniformly distributed throughout the cytoplasm and becomes recruited to GFP-labeled puncta, corresponding to autophagosomes, upon induction of autophagy by amino acid starvation (Fig. 2E). As a control, the proportion of parasites bearing GFP-labeled puncta in the GFP-TgAtg8 strain significantly increased from 4.9% ± 0.3% to 46.4% ± 3.9% after 8 h (p < 0.01) (Fig. 2F), as did the number of puncta per parasite (Fig. 2G and Table 1). As shown in Table 1, the proportion of parasites harboring three puncta significantly increased with time in the GFP-TgAtg8 strain (p < 0.05); there were even four and more puncta in some autophagosome-containing parasites after 8 h, indicating that autophagosome formation was induced successfully. However, we noticed that, after induction of the GFP-TgAtg8R27E mutant by starvation, although the number of parasites bearing GFP-labeled puncta slightly increased from 5.3% ± 0.4% to 10.1% ± 1% (p > 0.05), the number significantly decreased compared with the GFP-TgAtg8 control (p < 0.01) (Fig. 2F). In addition, the GFP-TgAtg8R27E mutant showed significant inhibition in autophagosome formation compared with the GFP-TgAtg8 control after 8-h starvation, as shown by the accumulation of autophagosome-containing parasites with mostly one or two puncta (Fig. 2G and Table 1), although the number of puncta per parasite did not significantly increase compared with preincubation. These results strongly suggest that the residues verified in this study are crucial for mediating the TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction and modulating the formation of autophagosomes in tachyzoites.

Table 1.

The proportions of parasites containing fluorescence-labeled TgAtg8–PE puncta

| Hours in HBSS | Group | Proportion of autophagosome-containing parasites with given number punctaa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1b | 2b | 3b | 4b | >4b | ||

| % | % | % | % | % | ||

| 0 | GFP-TgAtg8 | 76.2 ± 11.2 | 14.1 ± 4.9 | 9.3 ± 2.1a | 0 | 0 |

| GFP-TgAtg8R27E | 70.7 ± 10.4 | 20.4 ± 5.4 | 6.4 ± 2.6 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 0 | |

| 8 | GFP-TgAtg8 | 33.4 ± 9.6c | 24.2 ± 8.4 | 29.6 ± 9.0d | 11.4 ± 2.9 | 2.4 ± 0.7 |

| GFP-TgAtg8R27E | 63.4 ± 14.3c | 27.9 ± 7.4 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 0 | |

a The mean values ± S.E. from three independent experiments are presented.

b The number of puncta per parasite.

c There is a significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.05).

d There is a significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.01).

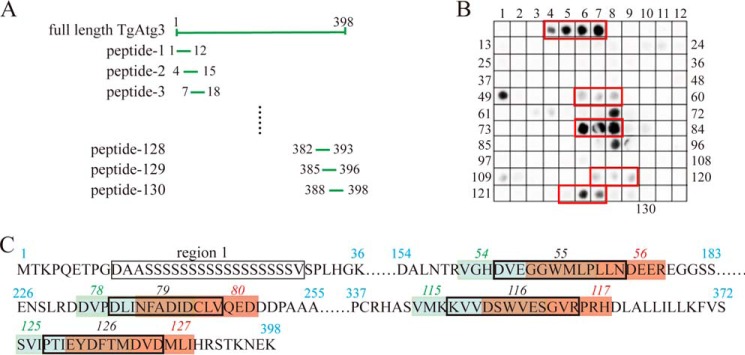

Detection of four candidate regions containing the TgAtg3 AIM by peptide array

To identify the candidate AIM sequence at which TgAtg3 may bind to TgAtg8, we performed an overlapping peptide assay containing 12-mers with a 3-amino acid shift to cover the full length of TgAtg3 (Fig. 3A). Considering the nature of the overlapping peptide sequences related to adjoining peptides, only series of consecutive positive spots were considered as potential binding regions. Additionally, the consensus for the core AIM is the ϴXXΓ motif, where ϴ is an aromatic residue, Γ is a hydrophobic residue, and X represents any other amino acid (23). Five separate and distinct regions were recognized on the TgAtg3 peptide array after incubation of the membrane with a recombinant TgAtg8 protein (Fig. 3, B and C). However, region 1 was considered a nonspecific reaction because all amino acid residues in this region are serines. These results indicate that four regions, TgAtg3163–174, TgAtg3235–246, TgAtg3346–357, and TgAtg3376–387, may be potential domains containing the AIM and are involved in the interaction with TgAtg8.

Figure 3.

Overlapping peptide assay screening of the peptide containing the AIM sequence in TgAtg3. A, schematic of full-length TgAtg3 and its peptides used to map the TgAtg8 interaction motif in TgAtg3. Arrays of 12-mer peptides covering the interacting region of full-length TgAtg3 were synthesized on cellulose membranes. Each peptide was shifted three amino acids relative to the previous peptide. B, peptide array scans analyzing the reaction of biotin-labeled TgAtg8 with 130 peptides of TgAtg3. The arrays were probed with biotin–His6–TgAtg8 and visualized with HRP-conjugated streptavidin. The spots in the red boxes indicate peptides containing a potential AIM sequence. C, sequence data for TgAtg8-interacting peptides. Blue numbers indicates the residue numbers of TgAtg3. Italic numbers represent the number of peptides. Sequences in brown boxes indicate the overlapping sequences between the sequences in blue boxes and those in red boxes.

The synthetic TgAtg3235–246 peptide remarkably inhibits the TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction

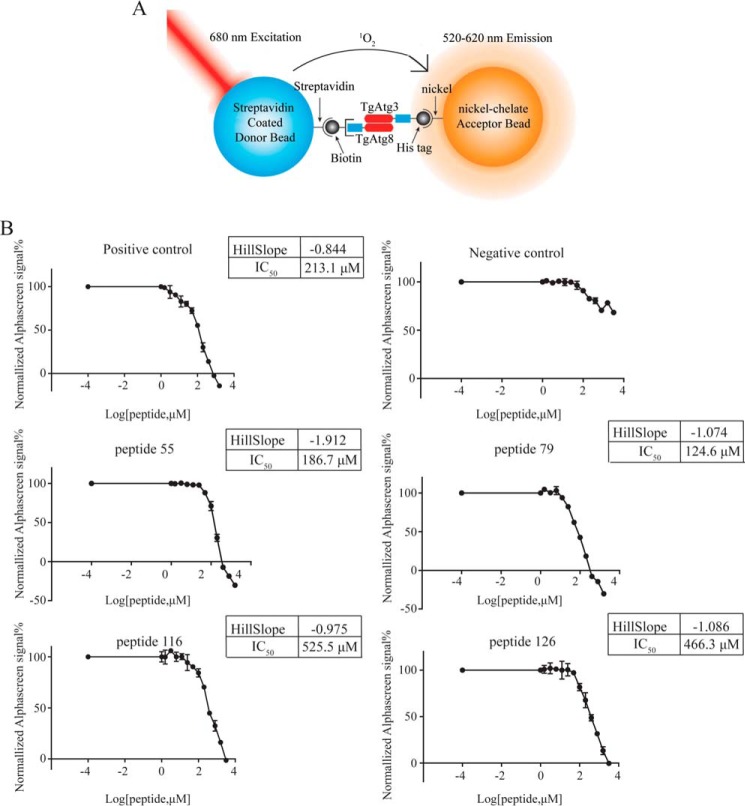

Although these potential regions were screened out, they may not represent actual binding domains because there are linear epitope peptides instead of conformational epitopes on the array membrane. To further verify which peptides contain the AIM sequence, the four peptides, indicated in Fig. 3C, were synthesized commercially and tested for their ability to block the interaction between full-length TgAtg8 and TgAtg3. In preliminary experiments, TgAtg8 incubated with peptides at a constant concentration of 200 μm was injected over a chip containing immobilized His6–TgAtg3, and the affinity of the interaction was measured. The BIAcore result showed that peptide 79 (TgAtg3235–246) dramatically inhibited the interaction of TgAtg8 with full-length TgAtg3 (Fig. S1). Based on this observation, we next employed the AlphaScreen assay to assess the inhibition ability of these peptides. A schematic illustration of the AlphaScreen assay is shown in Fig. 4A. In this assay, streptavidin-coated donor beads and nickel chelate acceptor beads were brought into close proximity through a biomolecular interaction. When the distance between donor and acceptor beads is within 200 nm, the excitation of the donor beads at 680 nm can release singlet oxygen molecules (1O2), triggering an energy conversion to the acceptor beads and leading to a sharp peak of emission at 570 nm (30). A significant reduction in luminescent signal intensity will be observed when the inhibitor disrupts the protein–protein interaction. To optimize the protein concentration for the assay, we performed independent matrix titrations of both interacting partners in the initial experiment. When the optimal concentration was determined to be 62.5 nm for both proteins, both the Z′ factor (0.60) and coefficient of variation (CV) (11.3%) exceeded the minimum pass criteria, indicating that the assay was robust and reliable.

Figure 4.

Identification of peptides containing a potential AIM sequence in TgAtg3 by AlphaScreen competition assay. A, schematic of the AlphaScreen assay. Biotinylated TgAtg8 and His-tag TgAtg3 are immobilized on streptavidin-coated donor beads and nickel-chelated acceptor beads, respectively. Excitation of donor beads produces singlet oxygen. Interaction between TgAtg8 and TgAtg3 brings donor and acceptor beads into close proximity, allowing energy from singlet oxygen to be transferred to the acceptor beads and produce a light signal. Addition of untagged competitor peptides will reduce the signal intensity. B, competition for binding to biotinylated TgAtg8 domain by untagged peptides of TgAtg3. Each competitor was tested in triplicate, with a representative data set shown. IC50 values were calculated using a nonlinear regression analysis (sigmoidal dose–response fitting with variable slope (four parameters)) using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software. Data were obtained from one of four independent experiments.

We next investigated whether the TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction could be disrupted by peptides using the AlphaScreen competitive binding assay. In the competitive binding assay, increasing concentrations of the unlabeled peptides were used to disrupt the association between the two interacting proteins, and the IC50 value was calculated from the range of increasing peptide concentrations. Given the high conservation of TgAtg8 and PfAtg8, a confirmed inhibitor of PfAtg8–PfAtg3 interaction, the PfAtg3103–110 peptide (28) was used as positive control. The TgAldolase421–432 peptide was used as a negative control. As shown in Fig. 4B, the negative control did not show the inhibitory effect. Compared with the negative control, all five peptides, including the positive control, exhibited considerable dose-dependent inhibitory activities. However, we only found that peptide 79 (TgAtg3235–246 peptide, 124.6 μm) and peptide 55 (TgAtg3163–174 peptide, 186.7 μm), particularly peptide 79, displayed significantly lower IC50 values for inhibiting the interaction of TgAtg8 and TgAtg3 than those of the positive control. We therefore selected the two peptides for further evaluation.

The core AIM in TgAtg3 is FADI, and several residues surrounding the AIM are crucial for the TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction

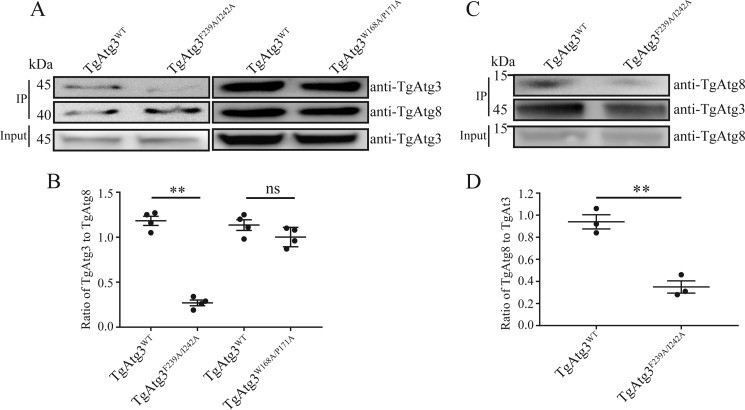

It has been verified that Atg8 directly recognizes a common motif, AIM, in Atg3. To identify the potential AIM in the two peptides of TgAtg3, therefore, we initially double-point-mutated residues in the TgAtg3235–246 peptide (Phe239 and Ile242) and in the TgAtg3163–174 peptide (Trp168 and Pro171) to alanine. The full-length mutants TgAtg3F239A/I242A and TgAtg3W168A/P171A fused separately to His tags were recombinantly expressed, and their ability of binding to TgAtg8 was tested using in vitro pulldown assays. As shown in Fig. 5, A and B, although the ability of TgAtg3W168A/P171A to bind to TgAtg8 was very similar to that of WT TgAtg3, TgAtg8 binding was remarkably reduced in TgAtg3F239A/I242A compared with the WT. Similar results were obtained from the ELISA (Fig. S2). We next tested whether recombinant TgAtg3 could interact with the endogenous TgAtg8 and evaluated the ability of TgAtg3F239A/I242A to bind to endogenous TgAtg8. Both TgAtg3WT and TgAtg3F239A/I242A were incubated separately with parasite lysate after being immobilized via a His tag. Bound proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using either anti-TgAtg3 or anti-TgAtg8 antibodies. A clear and similar density band could be observed in both samples with the anti-TgAtg3 antibody, indicating that similar recombinant TgAtg3 protein content was successfully purified. However, we found that the content of endogenous TgAtg8 decreased significantly in the TgAtg3F239A/I242A purified sample compared with the TgAtg3WT purified sample (Fig. 5, C and D). The result strongly suggests that the recombinant TgAtg3 proteins are properly folded and can interact with the endogenous TgAtg8. In addition, these findings clearly illustrate that the FADI sequence in TgAtg3 is the AIM.

Figure 5.

Confirmation of the AIM sequence in TgAtg3 and characterization of residues neighboring the core AIM. A, in vitro GST pulldown assays. GST-TgAtg8 was incubated with purified His6–TgAtg3 WT and mutant, followed by immobilization on GSH-Sepharose 4B. Binding was assessed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Four independent experiments with a combination of GST pulldown and Western blotting were performed. The image represents one of four independent experiments. IP, immunoprecipitation. B, binding was quantified with ImageJ as the ratio of bound TgAtg8 to TgAtg3. The mean values ± S.E. from four independent experiments are presented. **, p < 0.01; ns, not significant. C, TgAtg3 interaction with endogenous parasite TgAtg8. Both His6–TgAtg3 WT and mutant were incubated with protein extracts from tachyzoites of the RH ΔHX strain and then precipitated by Ni-NTA column elution. The precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Three independent experiments with a combination of His pulldown and Western blotting were performed. The image represents one of three independent experiments. D, binding was quantified with ImageJ as the ratio of bound TgAtg3 to TgAtg8. The mean values ± S.E. from three independent experiments are presented. **, p < 0.01.

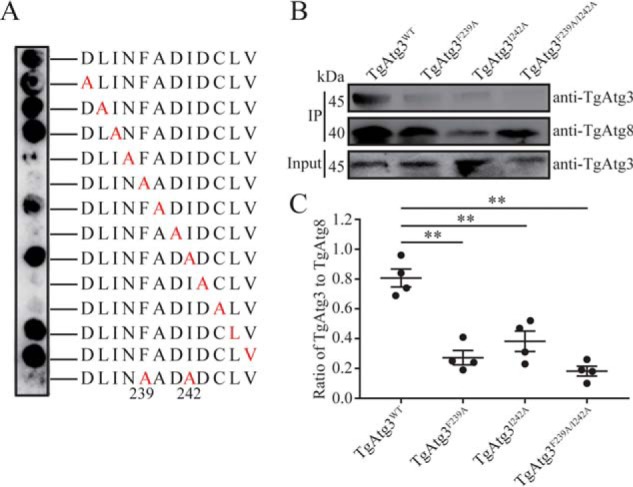

According to previously characterized AIM motifs, the consensus is X–3X–2X–1(W/Y/F)X1X2(L/I/V), with the (W/Y/F)X1X2(L/I/V) sequence as the core motif, in which the side chains of W/Y/F and L/I/V interact with the W-site and L-site of Atg8, respectively (23, 31). To further determine which residue in the TgAtg3235–246 peptide is important for the interaction, an alanine scanning assay was performed. We substituted each amino acid residue in the TgAtg3235–246 peptide with alanine successively and measured the interaction between these mutated peptides and TgAtg8 using a peptide array. Unexpectedly, within the FADI sequence, the I242A mutant was able to bind to TgAtg8, although the F239A and F239A/I242A mutants lost their ability to bind to TgAtg8 (Fig. 6A). Consideration of the spatial difference between linear peptide and full-length protein, recombinant full-length mutant His-TgAtg3F239A, and His-TgAtg3I242A was expressed separately, and their binding ability to TgAtg8 was tested using in vitro pulldown assays. As shown in Fig. 6, B and C, TgAtg8 binding was remarkably reduced in all TgAtg3 mutants compared with the WT. These results support the identification of an AIM sequence in TgAtg3, 239FADI242, responsible for TgAtg8 binding.

Figure 6.

Analyzing the effect of single amino acid substitutions at all positions of the indicated 12-mer peptides from TgAtg3 (amino acids 235–246). A, alanine scanning assay in which each position (red letters) of the 12-mer peptides was replaced with alanine. The array was probed with biotin–His6–TgAtg8 and visualized with HRP-conjugated streptavidin. B, in vitro GST pulldown assays. GST-TgAtg8 was incubated with purified His6–TgAtg3 WT and three mutants, followed by immobilization on GSH-Sepharose 4B. Binding was assessed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Four independent experiments with a combination of GST pulldown and Western blotting were performed. The image represents one of four independent experiments. IP, immunoprecipitation. C, binding was quantified with ImageJ as the ratio of bound TgAtg3 to TgAtg8. The mean values ± S.E. from four independent experiments are represented. **, p < 0.01.

In addition to the core AIM sequence, the X–3, X–2, and X–1 residues and the X1 and X2 residues are preferred by acidic residues. This preference is because acidic residues located at X–3, X–2, and X–1 may form ionic interactions with Lys46 and Lys48 of Atg8, whereas acidic residues located at X1 and X2 may form ionic interactions with Arg28 and Arg67 of Atg8, respectively. These characteristics could facilitate AIM to form a stretched β conformation upon binding to Atg8. However, in the case of the residues C-terminal to the L/I/V, there is no obvious preference for specific amino acids (23). In the TgAtg3235–246 peptide, the N238A, D241A, D243A, and C244A mutants also abolished their ability to bind to TgAtg8, indicating that these residues are important for the AIM to bind to TgAtg8 (Fig. 6). However, because of the spatial difference between linear peptide and full-length protein, more experiments should be designed to further evaluate the effect of these residues on the AIM-mediated TgAtg3–TgAtg8 interaction. Nevertheless, these findings still clearly indicate that the 239FADI242 sequence in TgAtg3 is the core and conserved AIM.

Discussion

The interaction between Atg8 and Atg3 has become a focus of the regulation of Atg8 lipidation and autophagosome formation. The TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction has been identified previously (24), but whether this interaction depends on a conserved mechanism, as determined in other species, has not been demonstrated. Here we show that TgAtg8 possesses conserved amino acid residues involved in the interaction with AIM. We also identified that TgAtg3 uses an AIM sequence (FADI) that is different from the AIM sequence (WLLP) in Plasmodium falciparum Atg3 (PfAtg3) to interact with TgAtg8. Furthermore, in vivo assays confirmed that TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction contributes to the TgAtg8–PE conjugation and formation of the autophagosome.

Recently, an apparently reduced but core autophagy machinery, Atg8 and its membrane conjugation system, has been identified in multiple species of protozoans. Several studies revealed that the Atg8 conjugation system in Plasmodium spp. and T. gondii is functionally conserved and indispensable for parasite survival (14, 15, 32). In Toxoplasma, the Atg8-decorated autophagosome-like structures could be found in tachyzoites upon stresses such as nutrient starvation or drug treatment (9, 15, 33). Moreover, the unusual apicoplast localization of Atg8 homologs in Plasmodium (34–36) and Toxoplasma (14, 37) suggests that Atg8 plays another important role distinct from autophagy. In Toxoplasma, prior to cytokinesis, TgAtg8 can be temporarily enriched to the elongating apicoplast for proper apicoplast division and inheritance into daughter cells (15, 37). Notably, in both Plasmodium and Toxoplasma, regardless of localization of Atg8 to either autophagosomal membranes or apicoplast membranes, the biological process is reliant on its conjugation to PE, highlighting the importance of the Atg8 conjugation system, particularly the Atg8–Atg3 interaction, in apicomplexans. In Plasmodium, PfAtg8–PfAtg3 interaction has been considered as an antimalarial drug target. Several small molecular inhibitors against Plasmodium in blood and liver stages have also been discovered (38, 39). However, a recent study verified that three PfAtg8–PfAtg3 interaction inhibitors identified in the Medicines for Malaria Venture Malaria Box do not block TgAtg8 lipidation, although all three inhibitors hinder Toxoplasma growth in a dose-dependent manner (40). Their findings suggest that the mechanism of Atg8–Atg3 interaction in Toxoplasma may be different from that in Plasmodium.

Structural characterization revealed that P. falciparum Atg8 contains conserved W- and L-site binding pockets and an Apicomplexa-specific loop (A-loop). To confirm the importance of these regions in mediating Atg8–Atg3 interaction, researchers mutated several residues in and near the two binding pockets and deleted residues 68–76, which formed the A-loop. Their results confirmed that, although the triple mutant E44A/K45S/K46A showed a moderate reduction in the binding of PfAtg8 to PfAtg3, the deletion of residues 68–76 and mutation of R27E strikingly decreased binding by 80% and 90%, respectively, suggesting that these two conserved pockets and the unique A-loop of PfAtg8 are necessary for interaction with PfAtg3 (28). In this work, TgAtg8 shows the greatest structural and sequence similarity to PfAtg8 and contains three conserved regions: the W-site, L-site, and A-loop. Our mutagenesis analysis confirms that these regions play an important role in mediating the TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction, which is consistent with the measured results of PfAtg8 (28). It has been verified that TgAtg8 is an essential protein for parasites and that its encoding gene cannot be knocked out. Therefore, elucidating the function of TgAtg8 in the Toxoplasma life cycle may be valuable and could be done using a specific small-molecule inhibitor or site-directed mutagenesis of these key residues mediating TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction in endogenous TgAtg8.

Because these residues of Atg8 involved in the interaction with the AIM are highly conserved in Toxoplasma and Plasmodium, we hypothesized that the difference in Atg8–Atg3 interaction is due to divergent AIM sequences. To date, only the crystal structure of Atg3 in S. cerevisiae has been solved. Structure studies revealed that ScAtg3 contains a conserved E2 core region and two insertions, the handle region (HR) and the flexible region (FR) (41). The HR, which is responsible for the interaction with the W-site and L-site of ScAtg8, has a conserved AIM sequence, WEDL (22). Our previous homology modeling has revealed that TgAtg3 contains the truncated HR (24), similar to that of the Plasmodium Atg3 (28). In this study, utilizing a combination of peptide array and AlphaScreen, we determined that the core AIM sequence in TgAtg3 is 239FADI242. The result coincides with the reported canonical AIMs in which the first position is tryptophan, phenylalanine, or tyrosine, and the fourth position is leucine, isoleucine, or valine (23). However, we noticed that the core AIM of TgAtg3 is different from that of PfAtg3, in which the core AIM sequence, 105WLLP108, is distinct from known motifs by the absence of leucine, isoleucine, or valine but the presence of proline at the fourth position in the motif (28). Moreover, it is worth noting that the TgAtg3163–174 peptide containing a WMLP sequence, similar to the AIM of PfAtg3, is also able to break the full-length TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction, although its inhibition effect is lower than that of the TgAtg3235–246 peptide. To exclude the unspecific inhibition, full-length mutant TgAtg3F239A/I242A and TgAtg3W168A/P171A were expressed to evaluate the ability of binding to full-length TgAtg8. These findings validated that the 239FADI242 sequence is the only AIM in TgAtg3. This result is not surprising because there are no acidic residues neighboring the WMLP sequence in TgAtg3. In contrast, neighboring the core AIM of PfAtg3, both X–3 (Asp102) and X–1 (Asp104) are acidic residues.

Furthermore, alanine scanning was performed to determine which amino acid in this motif is critical for the interaction with TgAtg8. Remarkably, besides the first and last residues of the core sequence, mutation of the third residue (X2), Asp241, also strongly abolished the ability of the motif to interact with TgAtg8, indicating that the third residue of the core motif is important. Additionally, residues neighboring the core motif, such as Asn238 at the N-terminal side of the core motif and Asp243 and Cys244 at the C-terminal side of the core motif, are also crucial to the interaction of TgAtg3 with TgAtg8. These results suggest that these acidic residues adjacent to the core motif should be considered when we want to ascertain the potential functional AIM sequences in TgAtg8-interacting proteins in T. gondii. For example, besides searching this core motif, the manual deletion of proline, glycine, and basic amino acid residues in the core motif must be applied.

Currently, targeting protein–protein interaction interfaces has been increasingly considered because of its importance and practicality (42–44). Recently, many compounds with antimalarial activity have been identified by inhibiting the recombinant PfAtg8–PfAtg3 interaction in vitro, suggesting that the Atg8–Atg3 interaction could be an attractive novel drug target in apicomplexan protozoans (28, 38, 39). In this study, we have developed a quantitative and straightforward AlphaScreen assay, which has enabled high-throughput screening of small-molecule modulators from compound libraries for multifarious biological targets. This platform would be beneficial for the identification of small molecular inhibitors specifically designed to disrupt the TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction in the future.

In summary, we report the core AIM sequence in TgAtg3 for T. gondii and elucidate the role of TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interactions in the regulation of TgAtg8 lipidation and autophagosome formation. In addition, we develop a high-throughput screening platform, AlphaScreen, that may not only offer a new strategy for identifying protein–protein interaction but can also be applied to screening small-molecule modulators against T. gondii.

Experimental procedures

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless specified otherwise. The primers used for cloning and mutagenesis are listed in Table S1.

Bioinformatics analysis

A sequence alignment between TgAtg8 and PfAtg8 was generated using Clustal Omega. Homology models were built by SWISS-MODEL using S. cerevisiae Atg8 (PDB code 3VH3) as a template. Three-dimensional structural analysis was performed using the PyMOL program. The crystal structure of P. falciparum Atg8 (PDB code 4EOY) was used as a reference. All calculations were carried out under default conditions.

Cloning, expression, and purification of TgAtg8

Recombinant protein His6–TgAtg8 was expressed and purified according to protocols reported previously (24). To generate both WT and mutant versions of GST-TgAtg8, coding sequences of TgAtg8R27E, TgAtg8D44A/K45S/K46A, and TgAtg8Δ68–76 were commercially synthetized (Genewiz, Suzhou, China) and directionally cloned into the pGEX-6p-1 expression vector, using BamH I and NotI to generate the corresponding plasmids pGST-TgAtg8R27E, pGST-TgAtg8D44A/K45S/K46A, and pGST-TgAtg8Δ68–76. All resulting plasmids were verified by restriction digestion and sequencing and then transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 cells. Protein expression was induced with 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at 37 °C for 4 h, and purification was performed with GSH-Sepharose 4B. All protein purification samples were assessed with SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Cloning, expression, and purification of TgAtg3

To express WT of TgAtg3, the plasmid pHis6–TgAtg3 constructed previously (24) was transformed into BL21 for expression and purification following the protocol published previously. The mutant versions of TgAtg3 and the mutant versions of TgAtg3, pHis6–TgAtg3F239A, pHis6–TgAtg3I242A, pHis6–TgAtg3F239A/I242A and pHis6–TgAtg3W168A/P171A, were synthesized using overlap PCR. Briefly, using pHis6–TgAtg3 as a template, the first round of PCR was performed using KAPA HiFi HotStart DNA polymerase (KAPA Biosystems) with corresponding primer sets: P1/P3 and P2/P10 for pHis6–TgAtg3F239A, P1/P5 and P4/P10 for pHis6–TgAtg3I242A, P1/P7 and P6/P10 for pHis6–TgAtg3F239A/I242A, as well as P1/P8 and P9/P10 for pHis6–TgAtg3W168A/P171A. The primer P1 contained an NdeI restriction enzyme site and His6 tag, and the primer P10 contained a HindIII restriction enzyme site. The primers P2/P3 and P4/P5 or P6/P7 and P8/P9 had 18-bp or 27-bp complementary sequences, respectively. Finally, the products of the first-round PCR were used separately as the templates to amplify the mutant full-length His6–TgAtg3 sequences with primer pair P1/P10. The resulting fragments were ligated into the pColdIII vector using NdeI and HindIII restriction sites. The resulting plasmids were verified with sequencing. The correct plasmids were transformed into BL21 cells, and protein expression was induced with 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at 15 °C for 22 h and further purified using an Ni-NTA–agarose affinity column as described previously.

Pulldown assays

All studies were carried out at 4 °C. To assess the interaction between TgAtg8 mutants and TgAtg3, purified His6–TgAtg3 was incubated separately with purified WT and mutant GST-TgAtg8 for 1 h and washed with 500 mm NaCl and 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.9). These mixtures were immobilized on an Ni-NTA–agarose affinity column (Qiagen) for 1 h. The bound proteins were washed with 1× PBS (pH 7.6) five times, resuspended in 100 μl of SDS-PAGE loading buffer, and denatured for 10 min at 95 °C. Finally, 20 μl of samples were used for SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

To assess the interaction between the TgAtg3 mutant and TgAtg8, purified GST-TgAtg8 was incubated separately with purified WT and mutant His6–TgAtg3 for 1 h prior to being immobilized on GSH-Sepharose 4B for 1 h. After washing, bound proteins were eluted with elution buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 50 mm reduced GSH) and analyzed as above.

To identify endogenous binding partners of TgAtg3 and evaluate the impact of Phe239 and Ile242 on TgAtg3 interaction, two 150-cm2 flasks of fresh extracellular tachyzoites of RH ΔHX were separately harvested and purified from host cell debris using 3.0-μm Nuclepore filters (Whatman, GE Healthcare). The parasite pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.5 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, and 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)) with Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche). Three cycles of freezing/unfreezing were performed to break the cells, followed by incubation for at least 1 h at 4 °C on a rotating wheel. The lysate was centrifuged for 20 min at 4 °C and 16,000 × g. The supernatant was incubated with purified His6–TgAtg3 or His6–TgAtg3F239A/I242A at 4 °C for 4 h. After immobilization on Ni-NTA columns for 1 h, the bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting as described.

Western blot analysis

Western blot assays were performed as described previously (24). For the identification of TgAtg8 lipidation, parasite lysates were separated by 6 m urea SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting.

Biotin conjugation

The biotin conjugation of TgAtg8 was performed using the EZ-LinkTM NHS-LC-LC-Biotin kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1 mg of either purified GST-TgAtg8 or His6–TgAtg8 was incubated separately with biotin for 2 h in an ice bath, followed by desalination. The biotin-TgAtg8 was quantified by the BCA method and further analyzed.

Peptide arrays

For the overlapping peptide array, peptides spanning the entire 398-amino acid sequence of TgAtg3 were prepared on derivatized cellulose membranes by Pepnoch Biotech Corp. Ltd. (Beijing, China). The peptides were 12 amino acids long and overlapped by nine residues. Therefore, each peptide on a membrane was shifted from the previous one by three amino acids toward the C-terminal end. The membrane was stored at −20 °C in a sealed bag until use. The arrangement of the 130 peptides on the membranes is illustrated in Fig. 3A.

For alanine scanning, each amino acid residue of the TgAtg3235–246 peptide fragment was mutated as alanine successively. Therefore, 14 peptides were synthesized and delivered to the derivatized cellulose membranes, which consisted of one original peptide, 12 peptides with a single mutation, and one peptide with a double mutation.

The peptide array membrane was activated by treating twice with methanol for 10 min at room temperature, followed by three washes with TBST (50 mm TBS and 0.2% Tween 20). After blocking with blocking buffer (4% skim milk and 5% sucrose in TBST) for 4 h at room temperature, the membrane was incubated with biotin–His6–TgAtg8 at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were then washed three times with TBST before being incubated with HRP-conjugated streptavidin (1:10,000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, specific binding on the membranes was then detected following treatment with ECL reagents. Visualization was performed using the ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Bio-Rad), and the optical densities of each positive spot were analyzed with the Spot Edge Average algorithm of TotalLab software.

AlphaScreen assay

The final concentrations of both biotin–TgAtg8 and His6–TgAtg3 were diluted to 62.5 nm with assay buffer (0.1% BSA in PBS (pH 7.4)). A volume of 4 μl of each diluted protein was added into a 384-well plate (OptiPlate-384, PerkinElmer Life Sciences, catalog no. 6007290) before addition of 4 μl of 12 2-fold dilution series of peptide starting at 1,600 μm in assay buffer for incubation at room temperature for 1 h. Preincubation of the mixture was followed by addition of 5 μl (0.1 μg) of nickel-chelated acceptor beads. After another 1-h incubation at room temperature, 5 μl (0.1 μg) of streptavidin-conjugated donor beads was added to the protein–peptide–acceptor beads mixture. This step was followed by a final incubation of 1 h in the dark at room temperature. The signal was detected by using multilabel reader Envision (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer's recommended settings (excitation, 680/30 nm, excitation time, 0.15 s; emission, 570/100 nm; measurement time, 600 ms). The mixture of biotin–TgAtg8 and His6–TgAtg3 without peptide was used as a positive signal control, and biotin–TgAtg8 protein alone was used as negative signal control. In total, six different peptides, TgAtg3163–174, TgAtg3235–246, TgAtg3346–357, TgAtg3376–387, TgAldolase421–432, and PfAtg3103–110, were tested in duplicate over a range of concentrations to determine IC50 value by AlphaScreen assay. Data were normalized to positive and negative signal controls. Individual IC50 curves for each peptide were plotted and fitted to a four-parameter sigmoidal model using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (San Diego, CA).

We calculated the inhibition rate with the following equation: inhibition rate (%) = [1 − (St − Sn)/(Sp − Sn)] × 100, where Sp (signal of positive control) is the value of the well containing both TgAtg8 and TgAtg3, Sn (signal of negative control) is the value of the well containing TgAtg8 alone, and St is the value of the well containing tested peptides.

To determine the robustness of the screening assay, three parameters, including the Z′ factor, CV, and signal/background (S/B) ratio were analyzed with the following equations,

| (Eq. 1) |

| (Eq. 2) |

| (Eq. 3) |

where SDn is the standard deviation of the negative signal control, SDp is the standard deviation of the positive signal control, Avgn is the average value of the negative signal control, and Avgp is the average value of the positive signal control. The primary screening data from the AlphaScreen campaigns were processed and subjected to the minimum pass criteria (Z′ ≥ 0.5, %CV ≤ 15%).

BIAcore analysis

The BIAcore analysis was conducted on a ProteOn XPR36 protein interaction array system (Bio-Rad). To measure the inhibition of TgAtg8–TgAtg3 interaction by peptides, the concentration of purified GST-TgAtg8 was adjusted to 75 μg/ml with PBS containing 0.1% SDS and 5% DMSO and incubated with peptides at a constant concentration of 200 μm for 30 min prior to BIAcore analysis. The sensor chip (ProteOnTM, 176-5033) was activated with 10 mm NiSO4 preconditioned with nickel prior to loading 50 μg/ml of purified His6–TgAtg3 in acetic acid buffer (pH 4.0). GST-TgAtg8 mixed with various peptides was injected over the chip at 30 μl/min. The association time was 80 s, and the dissociation time was 300 s. The data were collected and analyzed with ProteOn manager software as described previously (24).

ELISA

Flat-bottomed wells of 96-well ELISA plates (Corning) were coated with 100 μl of purified GST-TgAtg8 at 1 μg/ml overnight at 4 °C. After the plates were blocked with PBST containing 5% skim milk at 37 °C for 2 h, 100 μl of purified WT and mutant His6–TgAtg3 at 2 μg/ml was added and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After washing, the wells were incubated with 100 μl of 12 2-fold dilutions of rabbit anti-TgAtg3 antibody starting at 1:40 at 37 °C for 2 h. Afterward, 100 μl of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG was added for 1 h at 37 °C. The wells were washed extensively and incubated with 100 μl of tetramethylbenzidine substrate solution for 10 min, the reaction was stopped with 50 μl of 2.5 N H2SO4, and the optical density at 450 nm was detected with a microplate reader (Bio-Tek). All samples were run in triplicate.

Cloning of DNA plasmids for expression in Toxoplasma

To generate the pGFP-TgAtg8 mutant plasmids for expression of Atg8 in Toxoplasma, the coding sequences of full-length TgAtg8 were amplified using primer pair P11/P12 from the above plasmid pGST-TgAtg8R27E and cloned into the vector pGFP-TgAtg8 (15) using PstI and PacI to generate the corresponding plasmid pGFP-TgAtg8R27E. The resulting plasmid was verified with sequencing.

Host cells and parasite culture

Human foreskin fibroblast (hTERT) cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (pH 7.2) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. Cells were grown as monolayers in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Tachyzoites of either the RH ΔHX or GFP-TgAtg8 strain (15) were maintained by serial passage.

Generation of transgenic parasites

Freshly egressed tachyzoites of RH ΔHX were collected and filtered through a 3.0-μm Nuclepore filters (Whatman, GE Healthcare) to remove cellular debris. After centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 10 min, the pelleted parasites were resuspended in Cytomix (120 mm KCl, 0.15 mm CaCl2, 10 mm K2HPO4/KH2PO4 (pH 7.6), 25 mm HEPES, 2 mm EDTA, and 5 mm MgCl2 (pH 7.6)) complemented with 3 mm GSH and 3 mm ATP. The concentration of parasite was adjusted to 4–5 × 107/ml. Three hundred microliters of parasite suspension was transferred into a 4-mm gap cuvette for electroporation (900 V, 250-μs pulse length, 2 pulses with a 1-s interval on a BTX ECM 830 electroporator) with 100 μg of generated plasmids. Twenty-four hours after electroporation, transgenic parasites were selected with 25 μg/ml mycophenolic acid and 50 μg/ml xanthine for three passages, followed by cloning through limiting dilution in 96-well plates under drug selection. After isolation, GFP-expressing parasites were determined by observation under a Nikon ECLIPSE Ci-L epifluorescence microscope.

Immunoprecipitation of GFP-TgAtg8

One 75-cm2 flask of extracellular GFP-TgAtg8 or GFP-TgAtg8R27E parasites were collected and resuspended in 500 μl of lysis buffer as described above. At the end, 15 μl of lysate was collected as “input” for Western blot analysis. Centrifugation was performed at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to remove intact parasites. Supernatants were then diluted to half in wash buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, and 0.5 mm EDTA) with Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche) to decrease the detergent concentration. The diluted supernatant was added to 20 μl of Chromotek GFP-Trap magnetic agarose beads (GFP-Trap®_MA, gtma-10) and incubated at 4 °C for 4 h on a rotating wheel. The beads were washed three times in washing buffer, resuspended in 20 μl of SDS-PAGE loading buffer, and heated at 95 °C for 5 min for “elution.” The input and elution fraction were analyzed using SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-GFP and anti-TgAtg3 antibodies.

Induction of autophagy

To induce autophagy, extracellular tachyzoites cultured in 10% fetal bovine serum/Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium were collected from freshly lysed host cells and washed twice in prewarmed Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS, Invitrogen). The parasite pellets were resuspended in HBSS and incubated at 37 °C for 8 h. Autophagosomes were quantified by fluorescence microscopic observation, and the GFP punctum signals were counted.

Fluorescence microscopy

For fluorescence microscopy observation, parasites were made to adhere onto poly-l-lysine slides for at least 30 min and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Fluorescent images were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse Ci-L epifluorescence microscope, and the number of parasites bearing GFP-TgAtg8 puncta was quantified. At least 200 cells were counted in each TgAtg8 punctum experimental set.

Author contributions

S. Liu, F. Z., Y. W., H. W., X. C., M. C., S. Lan, C. W., and J. C. data curation; S. Liu, H. W., X. C., and S. Lan formal analysis; S. Liu, F. Z., X. H., and F. T. funding acquisition; S. Liu, F. Z., Y. W., H. W., Y. H., M. C., S. Lan, C. W., and J. C. methodology; F. Z. and Y. H. validation; Y. H. and X. H. conceptualization; M. C. resources; X. H. and F. T. supervision; X. H. project administration; F. T. writing-original draft.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. William J. Sullivan, Jr. (Indiana University School of Medicine) for providing the human foreskin fibroblast cells, Dr. Sébastien Besteiro (Universites de Montpellier) for the RH GFP-TgAtg8 parasite strain and pGFP-TgAtg8 plasmid, and Matt Young (La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology) for refining the language.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 81672052 and Zhejiang Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scientists Grant LR17H190001 (to F. T.), National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 81702024 and Commonwealth Technology Application Project Program of Zhejiang Province Grant 2015C33129 (to X. H.), Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province Grant LY16H190007 (to X. C.), Zhejiang Xinmiao Talent Plan Grant 2017R413062 (to S. L.), as well as Zhejiang Xinmiao Talent Plan Grant 2017R413019 (to F. Z.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1 and S2 and Table S1.

- PE

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- Tg

- Toxoplasma gondii

- AIM

- Atg8 family–interacting motif

- CV

- coefficient of variation

- FR

- flexible region

- HR

- handle region

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- HRP

- horseradish peroxidase

- HBSS

- Hanks' balanced salt solution

- Pf

- Plasmodium falciparum

- Sc

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae

- A-loop

- Apicomplexa-specific loop.

References

- 1. Sullivan W. J. Jr., and Jeffers V. (2012) Mechanisms of Toxoplasma gondii persistence and latency. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 717–733 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00305.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lüder C. G., Bohne W., and Soldati D. (2001) Toxoplasmosis: a persisting challenge. Trends Parasitol. 17, 460–463 10.1016/S1471-4922(01)02093-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cañón-Franco W. A., López-Orozco N., Gómez-Marín J. E. and Dubey J. P. (2014) An overview of seventy years of research (1944–2014) on toxoplasmosis in Colombia, South America. Parasit. Vectors 7, 427 10.1186/1756-3305-7-427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weiss L. M., and Dubey J. P. (2009) Toxoplasmosis: a history of clinical observations. Int. J. Parasitol. 39, 895–901 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sinai A. P., and Roepe P. D. (2012) Autophagy in Apicomplexa: a life sustaining death mechanism? Trends Parasitol. 28, 358–364 10.1016/j.pt.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lüder C. G., Campos-Salinas J., Gonzalez-Rey E., and van Zandbergen G. (2010) Impact of protozoan cell death on parasite-host interactions and pathogenesis. Parasit. Vectors 3, 116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reece S. E., Pollitt L. C., Colegrave N., and Gardner A. (2011) The meaning of death: evolution and ecology of apoptosis in protozoan parasites. PLOS Pathog. 7, e1002320 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Latré de Laté P., Pineda M., Harnett M., Harnett W., Besteiro S., and Langsley G. (2017) Apicomplexan autophagy and modulation of autophagy in parasite-infected host cells. Biomed. J. 40, 23–30 10.1016/j.bj.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ghosh D., Walton J. L., Roepe P. D., and Sinai A. P. (2012) Autophagy is a cell death mechanism in Toxoplasma gondii. Cell. Microbiol. 14, 589–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li X., Chen D., Hua Q., Wan Y., Zheng L., Liu Y., Lin J., Pan C., Hu X., and Tan F. (2016) Induction of autophagy interferes the tachyzoite to bradyzoite transformation of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitology 143, 639–645 10.1017/S0031182015001985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Besteiro S. (2012) Which roles for autophagy in Toxoplasma gondii and related apicomplexan parasites? Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 184, 1–8 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weidberg H., Shvets E., and Elazar Z. (2011) Biogenesis and cargo selectivity of autophagosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 125–156 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052709-094552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hurley J. H., and Schulman B. A. (2014) Atomistic autophagy: the structures of cellular self-digestion. Cell 157, 300–311 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kong-Hap M. A., Mouammine A., Daher W., Berry L., Lebrun M., Dubremetz J. F., and Besteiro S. (2013) Regulation of ATG8 membrane association by ATG4 in the parasitic protist Toxoplasma gondii. Autophagy 9, 1334–1348 10.4161/auto.25189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Besteiro S., Brooks C. F., Striepen B., and Dubremetz J. F. (2011) Autophagy protein Atg3 is essential for maintaining mitochondrial integrity and for normal intracellular development of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. PLOS Pathog. 7, e1002416 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nakatogawa H., Ichimura Y., and Ohsumi Y. (2007) Atg8, a ubiquitin-like protein required for autophagosome formation, mediates membrane tethering and hemifusion. Cell 130, 165–178 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Slobodkin M. R., and Elazar Z. (2013) The Atg8 family: multifunctional ubiquitin-like key regulators of autophagy. Essays Biochem. 55, 51–64 10.1042/bse0550051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stolz A., Ernst A., and Dikic I. (2014) Cargo recognition and trafficking in selective autophagy. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 495–501 10.1038/ncb2979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kirisako T., Ichimura Y., Okada H., Kabeya Y., Mizushima N., Yoshimori T., Ohsumi M., Takao T., Noda T., and Ohsumi Y. (2000) The reversible modification regulates the membrane-binding state of Apg8/Aut7 essential for autophagy and the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. J. Cell Biol. 151, 263–276 10.1083/jcb.151.2.263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tanida I., Mizushima N., Kiyooka M., Ohsumi M., Ueno T., Ohsumi Y., and Kominami E. (1999) Apg7p/Cvt2p: a novel protein-activating enzyme essential for autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 1367–1379 10.1091/mbc.10.5.1367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ichimura Y., Kirisako T., Takao T., Satomi Y., Shimonishi Y., Ishihara N., Mizushima N., Tanida I., Kominami E., Ohsumi M., Noda T., and Ohsumi Y. (2000) A ubiquitin-like system mediates protein lipidation. Nature 408, 488–492 10.1038/35044114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yamaguchi M., Noda N. N., Nakatogawa H., Kumeta H., Ohsumi Y., and Inagaki F. (2010) Autophagy-related protein 8 (Atg8) family interacting motif in Atg3 mediates the Atg3-Atg8 interaction and is crucial for the cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 29599–29607 10.1074/jbc.M110.113670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Noda N. N., Ohsumi Y., and Inagaki F. (2010) Atg8-family interacting motif crucial for selective autophagy. FEBS Lett. 584, 1379–1385 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen D., Lin J., Liu Y., Li X., Chen G., Hua Q., Nie Q., Hu X., and Tan F. (2016) Identification of TgAtg8-TgAtg3 interaction in Toxoplasma gondii. Acta Trop. 153, 79–85 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sugawara K., Suzuki N. N., Fujioka Y., Mizushima N., Ohsumi Y., and Inagaki F. (2004) The crystal structure of microtubule-associated protein light chain 3, a mammalian homologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Atg8. Genes Cells 9, 611–618 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00750.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Noda N. N., Kumeta H., Nakatogawa H., Satoo K., Adachi W., Ishii J., Fujioka Y., Ohsumi Y., and Inagaki F. (2008) Structural basis of target recognition by Atg8/LC3 during selective autophagy. Genes Cells 13, 1211–1218 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01238.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koopmann R., Muhammad K., Perbandt M., Betzel C., and Duszenko M. (2009) Trypanosoma brucei ATG8: structural insights into autophagic-like mechanisms in protozoa. Autophagy 5, 1085–1091 10.4161/auto.5.8.9611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hain A. U., Weltzer R. R., Hammond H., Jayabalasingham B., Dinglasan R. R., Graham D. R., Colquhoun D. R., Coppens I., and Bosch J. (2012) Structural characterization and inhibition of the Plasmodium Atg8-Atg3 interaction. J. Struct. Biol. 180, 551–562 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ho K. H., Chang H. E., and Huang W. P. (2009) Mutation at the cargo-receptor binding site of Atg8 also affects its general autophagy regulation function. Autophagy 5, 461–471 10.4161/auto.5.4.7696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ullman E. F., Kirakossian H., Singh S., Wu Z. P., Irvin B. R., Pease J. S., Switchenko A. C., Irvine J. D., Dafforn A., and Skold C. N. (1994) Luminescent oxygen channeling immunoassay: measurement of particle binding kinetics by chemiluminescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 5426–5430 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johansen T., and Lamark T. (2011) Selective autophagy mediated by autophagic adapter proteins. Autophagy 7, 279–296 10.4161/auto.7.3.14487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Walker D. M., Mahfooz N., Kemme K. A., Patel V. C., Spangler M., and Drew M. E. (2013) Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stage parasites require the putative autophagy protein PfAtg7 for normal growth. PLoS ONE 8, e67047 10.1371/journal.pone.0067047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lavine M. D., and Arrizabalaga G. (2012) Analysis of monensin sensitivity in Toxoplasma gondii reveals autophagy as a mechanism for drug induced death. PLoS ONE 7, e42107 10.1371/journal.pone.0042107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tomlins A. M., Ben-Rached F., Williams R. A., Proto W. R., Coppens I., Ruch U., Gilberger T. W., Coombs G. H., Mottram J. C., Müller S., and Langsley G. (2013) Plasmodium falciparum ATG8 implicated in both autophagy and apicoplast formation. Autophagy 9, 1540–1552 10.4161/auto.25832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kitamura K., Kishi-Itakura C., Tsuboi T., Sato S., Kita K., Ohta N., and Mizushima N. (2012) Autophagy-related Atg8 localizes to the apicoplast of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS ONE 7, e42977 10.1371/journal.pone.0042977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jayabalasingham B., Voss C., Ehrenman K., Romano J. D., Smith M. E., Fidock D. A., Bosch J., and Coppens I. (2014) Characterization of the ATG8 conjugation system in 2 Plasmodium species with special focus on the liver stage: possible linkage between the apicoplastic and autophagic systems? Autophagy 10, 269–284 10.4161/auto.27166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leveque M. F., Berry L., Cipriano M. J., Nguyen H. M., Striepen B., and Besteiro S. (2015) Autophagy-related protein ATG8 has a noncanonical function for apicoplast inheritance in Toxoplasma gondii. mBio 6, e1415–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hain A. U., Miller A. S., Levitskaya J., and Bosch J. (2016) Virtual screening and experimental validation identify novel inhibitors of the Plasmodium falciparum Atg8-Atg3 protein-protein interaction. ChemMedChem 11, 900–910 10.1002/cmdc.201500515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hain A. U., Bartee D., Sanders N. G., Miller A. S., Sullivan D. J., Levitskaya J., Meyers C. F., and Bosch J. (2014) Identification of an Atg8-Atg3 protein-protein interaction inhibitor from the Medicines for Malaria Venture Malaria Box Active in blood and liver stage Plasmodium falciparum parasites. J. Med. Chem. 57, 4521–4531 10.1021/jm401675a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Varberg J. M., LaFavers K. A., Arrizabalaga G., and Sullivan W. J. (2018) Characterization of Plasmodium Atg3-Atg8 interaction inhibitors identifies novel alternative mechanisms of action in Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 62, e01489–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yamada Y., Suzuki N. N., Hanada T., Ichimura Y., Kumeta H., Fujioka Y., Ohsumi Y., and Inagaki F. (2007) The crystal structure of Atg3, an autophagy-related ubiquitin carrier protein (E2) enzyme that mediates Atg8 lipidation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 8036–8043 10.1074/jbc.M611473200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dickson M. A., Okuno S. H., Keohan M. L., Maki R. G., D'Adamo D. R., Akhurst T. J., Antonescu C. R., and Schwartz G. K. (2013) Phase II study of the HSP90 inhibitor BIIB021 in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann. Oncol. 24, 252–257 10.1093/annonc/mds275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rudin C. M., Hann C. L., Garon E. B., Ribeiro de Oliveira M., Bonomi P. D., Camidge D. R., Chu Q., Giaccone G., Khaira D., Ramalingam S. S., Ranson M. R., Dive C., McKeegan E. M., Chyla B. J., Dowell B. L., et al. (2012) Phase II study of single-agent navitoclax (ABT-263) and biomarker correlates in patients with relapsed small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 3163–3169 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brennan R. C., Federico S., Bradley C., Zhang J., Flores-Otero J., Wilson M., Stewart C., Zhu F., Guy K., and Dyer M. A. (2011) Targeting the p53 pathway in retinoblastoma with subconjunctival Nutlin-3a. Cancer Res. 71, 4205–4213 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.