Abstract

Background

In the management of knee osteoarthritis (OA), patient-reported-outcomes (PROs) are being developed for relevant assessment of pain. The patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) is a relevant cutoff, which allows classifying patients as being in “an acceptable state” or not. Viscosupplementation is a therapeutic modality widely used in patients with knee OA that many patients are satisfied with despite meta-analyses give conflicting results.

Objectives

To compare, 6 months after knee viscosupplementation, the percentage of patients who reached the PASS threshold (PASS +) with that obtained from other PROs.

Methods

Data of 53 consecutive patients treated with viscosupplementation (HANOX-M-XL) and followed using a standardized procedure, were analyzed at baseline and month 6. The PROs were Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain and function, patient’s global assessment of pain (PGAP), patient’s self-assessment of satisfaction, PASS for WOMAC pain and PGAP.

Results

At baseline, WOMAC pain and PGAP (range 0-10) were 4.6 (1.1) and 6.0 (1.1). At month 6, they were 1.9 (1.2) and 3.1 (5) (P < 0.0001). At 6 months, 83% of patients were “PASS + pain,” 100% “PASS + function,” 79% “PASS + PGAP,” 79% were satisfied, and 73.6% experienced a ≥50% decrease in WOMAC pain. Among “PASS + pain” and “PASS + PGAP” subjects, 90% and 83.3% were satisfied with the treatment, respectively.

Conclusion

In daily practice, clinical response to viscosupplementation slightly varies according to PROs. “PASS + PGAP” was the most related to patient satisfaction.

Keywords: hyaluronic acid, viscosupplementation, knee osteoarthritis, intra-articular injection, PASS, WOMAC, patient-reported outcome

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a major cause of pain and disability in subjects older than 50 years with a significant impact on physical performance and quality of life. However, knee OA is not the exclusive preserve of elderly and also affects younger people, especially those having had a severe knee injury.1 Total knee replacement (TKR) is an effective intervention for patients with severe knee OA symptoms. However, the decision-making process of TKR surgery is extremely complex and depends on numerous factors.2 Furthermore, a number of patients never progress to a level where surgery is considered necessary. Consequently, standard conservative therapy for knee OA should last many years. It includes a combination of non-pharmacological (i.e., weight loss, physical activity development, rehabilitation, etc.) and pharmacological approaches,3-6 as none individually can be considered highly effective, if one refers to the size effect of each of them.4,5 The size effects of the recommended pharmacological modalities range from 0.18 for the least efficacious treatment (acetaminophen) to 0.63 for viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid (HA).7 Compared with intra-articular (IA) steroids, from injection to week 4, IA HA injections were shown to be less effective than steroids. However, by week 4, the 2 approaches had equal efficacy, and beyond week 8, HA had greater efficacy.8 A large scale internet-based survey, performed in 5 European countries, including 2073 patients, ranked IA injections of HA as the patients’ preferred treatment for knee OA.9 However, many controversies exist in the clinical relevance of their effects.10-15 Rutjes et al10 concluded from their meta-analysis that viscosupplementation was associated with a small and clinically irrelevant benefit and an increased risk for serious adverse events. The same conclusions were drawn by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons15 who recommended against the use of viscosupplementation for failing to meet the criterion of minimum clinically important improvement (MCII)16 to which Bannuru et al17 replied that even applied appropriately, MCII can be a useful tool for comprehensive presentation of study results but should not be a cornerstone of clinical decision making. Indeed, the choice of outcome measures is a major step in the design of clinical trials and to interpret adequately their results. There are many other tools for assessing pain and disability in OA patients18-22 that can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments. Trials in the field of OA, usually evaluate pain, functional impairment, and patient global assessment. However, none of the validated patient-reported outcomes (PROs) can be considered individually as “the gold standard.” Thus, the choice of the PROs can lead to significant differences in the interpretation of the results, which might explain, at least in part, discrepancy between the self-reported patients’ opinion in daily practice, and the conclusions of several studies and meta-analyses.23 It should, however, be pointed out other explanations of controversy such as the insufficient statistical power of some trials, poor techniques of injection and poor patient selection.

Chronic pain, the main symptom of OA, is a very complex phenomenon.24,25 The International Association for the Study of Pain defines chronic pain as an “unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described by the patient in terms of such damage.”26 The relationship between pain perception and cognitive function is of major importance in the understanding of the information that can be obtained from the measurement of pain and disability. In daily clinical practice, physicians frequently ask 2 questions to patients for assessing the effectiveness of a treatment: “are you feeling better” and “are you feeling good?” Unsurprisingly it has been demonstrated that patients prioritize on feeling good than on feeling better.27 The patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) is a clinically relevant cutoff, which allows to assess the individual clinical status of a patient, at a given time, by classifying him or her as being in “an acceptable state” (score ≤PASS threshold) or not (score >the PASS threshold).28 In other words, PASS can be defined as the highest level of symptoms beyond which patients consider themselves well. The PASS introduces the concept of wellbeing or remission of symptoms and has been demonstrated to be a clinically relevant outcome for the patient.16,28 The PASS for the normalized Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain subscore (0-10) was shown to be 4/10 in patients with knee and hip OA, subject to some variations related to the country or method of collection.29,30 For example, the average PASS, obtained from WOMAC pain subscore, was 39/100, varying according the countries, from 26 (France) to 53 (Italy). When PASS was obtained from WOMAC function subscore its mean value was 45 ranging from 29 (Spain) to 53 (Italy).30 In a large-scale multicenter cohort study of 2414 patients with painful knee or hip OA, Perrot and Bertin31 showed that the improvement, assessed with PASS, was smaller in daily practice conditions than that recorded in randomized controlled trials. On the contrary we feel, from our long-time experience in viscosupplementation therapy, the percentage of patients with knee OA who are satisfied with HA injections is higher in the daily practice than that reported in controlled trials. In a recent review, effectiveness of IA HA has been highlighted based on “real-life” data, together with the clinical benefit of systematic repeated treatment cycles, and the influence of the molecular weight of HA on treatment outcome.32

Assuming that the caregiver’s objective is that patients are satisfied with the treatment, we hypothesized that a state-attainment criterion, such as the PASS, has to be preferred to a responder criterion to assess the individual clinical status of a patient at a given time. To confirm or refute this hypothesis we have studied the relationship between patient’s satisfaction (yes/no) and several validated PROs, including PASS pain and function, PASS global assessment of pain and changes over time of WOMAC score.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

The present work is the analysis of data obtained, in daily practice conditions, from a cohort of patients with knee OA, referred to the department of rheumatology of the North Franche-Comté hospital for viscosupplementation. In accordance with the French Authorities recommendations viscosupplementation is performed only in patients suffering from knee OA not sufficiently improved by the first-line treatments, including analgesics and non-pharmacological modalities. In our department, all patients requiring HA injections for knee OA are assessed using the same standardized questionnaire at the time of injection(s) and then at each visit, irrespective of the time interval or the viscosupplement agent. Before treatment, patients consented to the scientific and anonymous usage of the data collected during consultations. This prospective analysis fell within the scope of observational study and did not need a National Ethics Committee approval. The Hôpital Nord Franche-Comté scientific and ethics committee approved the study protocol. The standardized questionnaires included anthropometric and demographic data, medical history of knee OA, prior and present treatments for knee OA, Patient’s Global Assessment of the Knee Pain (PGAP) using a 11-box numerical rating scale (NRS, range 0-10) and WOMAC19 using NRS for each of the 24 items (0-24). For easier comparison of PASS obtained from different questionnaires (WOMAC pain 50 points, WOMAC function 170 points, PGAP 10 points) all values were normalized to scores with a 0–10 range, by dividing the total score by the number of items of the questionnaire). A radiographic evaluation of the target knee at baseline was performed by a single experienced observer to determine the involved compartment(s) (medial tibiofemoral, lateral tibiofemoral, patella-femoral) and to score the most affected one using the Kellgren-Lawrence33 and the OARSI (Osteoarthritis Research Society International) grading scales.34

Treatment

To avoid bias due to differential effects between treatments our study group included only patients who were treated with a single IA injection of HAnox-M-XL (Happycross, LABRHA SAS, Lyon, France). This particular viscosupplement was chosen as it was the most used one during the selected period. HAnox-M-XL is a cross-linked sodium hyaluronate concentrated at 16 mg/mL combined with a high concentration (3.5%) of mannitol, conferring a very high viscosity35 allowing a single injection regimen. HAnox-M-XL is supplied as a syringe containing 2.2 mL of solution. The content of one syringe was injected into the target knee through a 21-gauge needle, after careful removal of synovial fluid effusion if present, by experienced rheumatologists using a lateral mid-patellar approach.

Because the present study was not a clinical trial but the retrospective analysis of data, obtained prospectively from standardized questionnaires, no concomitant treatment was prohibited. The names and daily doses of concomitant therapies, such as analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), symptomatic slow acting drugs for OA were collected and recorded. In the event that a subject has been treated with IA steroids during the follow-up, it would not be included in the analysis

Efficacy Outcome Measures

The primary efficacy PRO was the number and percentage of patients reaching the PASS threshold (PASS +) for normalized WOMAC pain subscore (0-10) at 6 months after injection.

As the WOMAC pain is a composite index made of 5 questions, we also analyzed the PASS obtained from the Patient’s Global Assessment of Pain (PASS PGAP), which summarized in only one question as the pain perceived by the patient in his or her daily life. PASS function was also assessed from WOMAC function subscore. PASS thresholds were those previously published: “PASS+” if WOMAC pain ≤4/10, “PASS+ PGAP” if PGAP <4/10,22 and “PASS+ function” if WOMAC function <5/10.23,24 Other PROs were the absolute and relative changes in WOMAC total and subscores, and PGAP scores between injection and month 6. At month 6, patients were also asked to self-assess the treatment efficacy (0 = null, 1 = mild, 2 = good, 3 = very good) and their level of satisfaction with the therapy (0 = not satisfied, 1 = rather satisfied, 2 = satisfied, 3 = very satisfied). The variation in analgesic consumption was also self-assessed by the patient using a 5-point scale (0; ≤25%; 26%-50%, 51%-75%; >75%).

Safety Evaluation

Despite not being a drug evaluation study, adverse events (AEs) were recorded because satisfaction with a treatment may be widely influenced by the tolerability. AEs were collected in accordance with the European standard EN ISO 14155: 2011. They were recorded with particular note for those occurring immediately and the very next days after injection. The investigator scored all recorded AE for severity as “mild, moderate, or severe.” The investigator also assessed the causal relationship as “excluded” or “not excluded” with the treatment and/or the procedure of IA injection. All AEs whose occurrence could not reasonably be attributed to causes other than the injected treatment were considered potential reactions to it and the relationship was hence assessed as “not excluded.”

Statistics

The XLstats 2015 (Addinsoft) software was used for carrying out the statistical analyses. Descriptive statistical analyses (means, standard deviations, medians, percentages, confidence intervals) were used to describe the demographics, history of the disease, treatments, clinical and radiological examinations, treatment effectiveness and AEs. Baseline and 6-month follow-up characteristics are presented as number (%) or mean (95% CI). A Mann-Whitney or a chi-square was used to assess the association of quantitative or qualitative factors and PASS. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify predictors of PASS+ and included sex, age, body mass index (BMI), WOMAC pain and function at baseline and other factors with P < 0.20 on univariate analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed on the intent-to-treat population.

Results

During the 6-month study period, 53 consecutive patients were treated with HAnox-M-XL injection using the same default technique. Thirty-five were women and 18 were men, with bilateral knee involvement in 35 patients. Fifty patients had concomitant simple analgesics or NSAIDS and 28 patients had SYSADOA (symptomatic slow acting drugs for osteoarthitis). Previous IA injection(s) of corticosteroids or HA were reported in 33 and 35 patients, respectively. Osteoarthritis affected the tibiofemoral compartments in 93 %, (medial in 65% and lateral in 28%) while in 7% only the patellofemoral joint was involved. The grade of OA—Kellgren-grade—was I, II, III, and IV in 2, 18, 23, and 10 patients, respectively. Other demographic and clinical data at baseline are summarized in Table 1 . Complete data sets were available for all subjects with an average follow-up of 28 weeks (range 18-32).

Table 1.

Patients Characteristics at Baseline (N = 53).

| Items | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 62.6 | 12.3 | 39-87 |

| Height, cm | 164.9 | 7.2 | 150-179 |

| Weight, kg | 74.9 | 15.2 | 40-107 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.5 | 5.2 | 17.8-40.2 |

| Disease duration months | 54 | 36.5 | 3-180 |

| Normalized WOMAC pain subscore (0-10) | 4.5 | 1.2 | 2.6-7.2 |

| Normalized WOMAC function subscore (0-10) | 3.9 | 1.2 | 1.6-6.3 |

| Normalized WOMAC total (0-10) | 3.9 | 1.2 | 1.1-6.5 |

| PGAP (0-10) | 6.0 | 1.1 | 4-8 |

BMI = body mass index; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; PGAP = Patient’s Global Assessment of Pain.

Tables 2 and 3 summarizes the efficacy outcomes at baseline and at month 6. Mean (SD) variations in WOMAC pain and function subscores over follow-up were −2.6 (1.1) and −2.1 (0.9), respectively (P = 0.0001) It was −2.9 (1.3) for PGAP. This corresponded to relative changes of 58%, 51.2%, and 48.5%, respectively, in these parameters. All efficacy outcome and their variations highly correlated between themselves (all Ps <0.0001). PGAP score was significantly higher than WOMAC pain and WOMAC function subscores as well as than the items 1, 3, 4, and 5 of WOMAC pain (all Ps <0.001). However, there was no statistically significant difference between PGAP and item 2 of WOMAC pain (pain at stair climb up and down), suggesting that pain score reported by patients in PGAP is mainly due to pain occurring in the most painful situation such as going up and down the stairs.

Table 2.

Efficacy Outcome Measures at Baseline.

| Outcomes | WA1 | WA2 | WA3 | WA4 | WA5 | WA1-5 | PGAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 |

| Median | 5 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4.4 | 6 |

| Mean | 2.74 | 3.98 | 4.02 | 4.48 | |||

| SD | 1.28 | 1.19 | 2.50 | 1.88 | 2.16 | 1.17 | 1.15 |

WA1 to WA5 = Items 1 to 5 of WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) pain subscore on a 11-point rating numeric scale (0-10); WA1-5: WOMAC pain subscore normalized on a 11-point rating numeric scale (0-10); PGAP = Patient’s Global Assessment of Pain on a 11-point rating numeric scale (0-10).

Table 3.

Efficacy Outcome Measures at Month 6.

| Outcomes | WA1 | WA2 | WA3 | WA4 | WA5 | WA1-5 | PGAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 |

| Median | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1.6 | 3 |

| Mean | 2.45 | 0.59 | 1.36 | 1.81 | 1.83 | ||

| SD | 1.62 | 1.50 | 1.24 | 1.48 | 1.61 | 1.05 | 1.51 |

WA1 to WA5 = Items 1 to 5 of WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) pain subscore on a 11-point rating numeric scale (0-10); WA1-5 = WOMAC pain subscore normalized on a 11-point rating numeric scale (0-10); PGAP = Patient global assessment of pain on a 11-point rating numeric scale (0-10).

In paired Student t test WA2 and PGAP were significantly higher than other outcomes measures (all P values <0.001) and were not statistically different between themselves (P > 0.05).

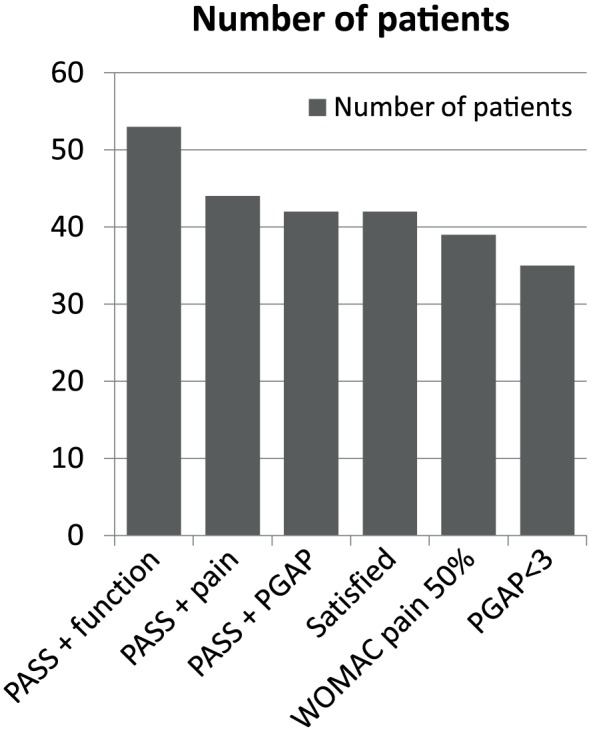

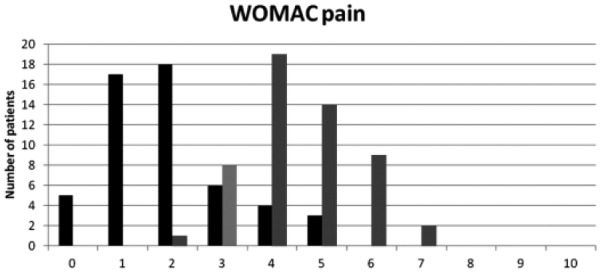

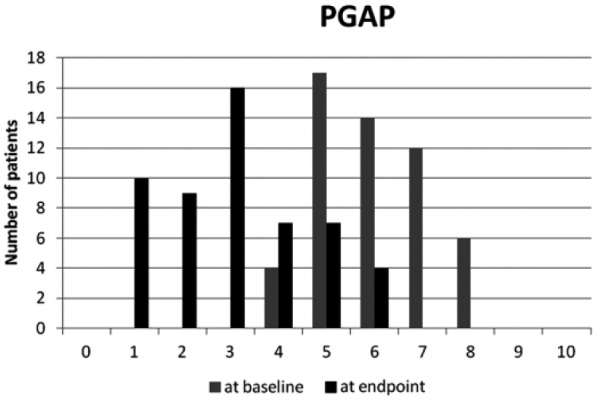

The number and percentage of patients fulfilling the response criteria at 6 months are summarized in Table 4 and Figure 1 . Unsurprisingly efficacy and satisfaction were highly correlated (P < 0.0001). Among “PASS+ pain” subjects 90% were satisfied with treatment whereas among the patients “PASS− pain,” 33% were still satisfied. Among “PASS+ PGAP” subjects, 83.3% were satisfied with treatment whereas among the “PASS− PGAP” patients 26.4% were still satisfied. In the 35 patients (66%) with PGAP ≤3 at month 6, 100% considered treatment as efficacious and were satisfied with it. In those with PGAP >3 at month 6, seven (39%) patients remain however satisfied. Interestingly “PASS+ PGAP” was better correlated with satisfaction (χ2 = 8.38, P = 0.004) than “PASS+ pain” (χ2 = 4.21, P = 0.04). Figure 2 shows the number of patients according to WOMAC pain subscore categories (numerical rating scale 0-10) at baseline and 6 months. It is clear that a large majority of patients score below 4, six months after treatment while most of them were over 4 before HA injection. Figure 3 shows the number of patients according to PGAP categories at baseline and 6 months after viscosupplementation.

Table 4.

Number and Percentage of Patients Fulfilling the Response Criteria at Month 6.

| Patient-Reported Outcomes | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| PASS+ pain | 44 (83) | 16 (17) |

| PASS+ function | 53 (100) | 0 (0) |

| PASS+ PGAP | 42 (79) | 11 (21) |

| PGAP < 3 | 35 (6) | 18 (44) |

| WOMAC pain decrease >50% | 40 (73.6) | 13 (26.4) |

| Efficacy | 41 (77.3) | 12 (22.7) |

| Satisfaction | 42 (79) | 11 (21) |

PGAP = Patient’s Global Assessment of Pain on a 11-point rating numeric scale (0-10); WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; PASS + pain = WOMAC pain subscore ≤4 normalized on a 11-point rating numeric scale (0-10); PASS + function = WOMAC function subscore ≤5 normalized on a 11-point rating numeric scale (0-10); PASS + PGAP = Patient’s Global Assessment of Pain ≤4 on a 11-point rating numeric scale (0-10).

Figure 1.

Number of patients (N = 53) fulfilling the responder criteria according to the outcome measures (N = 53).

PASS = Patient Acceptable Symptom State; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index; WOMAC pain 50% = Decrease of 50% or more in WOMAC pain subscore; PGAP = Patient’s Global Assessment of Pain (on a 10-point numerical rating scale).

Figure 2.

Number of patients according to WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index) pain subscore categories (numerical rating scale 0-10) at baseline (gray bars) and 6 months after viscosupplementation (black bars) (N = 53). The figure shows that 44 patients ranked pain 4 to 7 at baseline. They were only 7 at 6 months. Conversely, only 9 patients ranked pain at less than 4 at baseline versus 46 at 6 months.

Figure 3.

Number of patients according to Patient’s Global Assessment of Pain (PGAP) categories (numerical rating scale 0-10) at baseline and 6 months after viscosupplementation (N = 53).

On predictive factors of response to treatment, a higher BMI was associated with a lower rate of PASS+ (P = 0.1). The difference was more significant between obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) and nonobese subjects (P = 0.03). Improvement was unrelated to age, gender, X-ray grade, joint space narrowing location, presence or absence of joint effusion and disease duration (all Ps >0.05). At baseline, 39 patients were taking analgesics or NSAIDs. Among them 84.7% reduced their analgesic/NSAIDs consumption between baseline and 6 months. The reduction was more than 50% in 66.6% of the cases.

AEs were observed in 3 patients (5.7%). These 3 patients were PASS+ pain at month 6 and 2 were satisfied with the treatment. All adverse reactions were transient worsening of pain in the target knee that occurred a few hours after injection, which resolved without sequel between 36 and 72 hours. Neither occurrence of effusion, nor systemic AE was reported. No SAE occurred during the follow-up.

Discussion

The present study was not designed to demonstrate the efficacy of knee viscosupplementation. In the absence of a control group, and because other treatments for OA were continued throughout the follow-up, its real effectiveness cannot be asserted conclusively. The goal of the trial was to define the PRO(s) that match(es) the best with the patient’s satisfaction 6 months after injection. The main conclusion was that there was very few differences between the studied PROs but that PASS better correlates with patient’s satisfaction than the decrease of pain.

Three main issues are emphasized by these results. First, they begin to address some of those unanswered questions about discrepancies between results of clinical trials and daily clinical practice that are frequently observed. Most of the controlled clinical studies demonstrate, at best, a mild to moderate effect of viscosupplementation in patients with knee OA.8,10-14 On the contrary, several studies showed that about 75% of patients are satisfied with viscosupplementation.9,36,37 In our cohort of patients, the decrease of pain over time was statistically very significant but its clinical relevance (i.e., −2.6 points on NRS) can be considered debatable. WOMAC pain subscore, the PRO that is usually chosen as the primary criterion of efficacy in most of randomized controlled trials, decreased from 4.5 to 1.8 throughout the follow-up making a 60% improvement that is much greater than the MCII threshold.16 However, if one considers the clinical effect of viscosupplementation from 82%38 to 46%8 may be due to contextual effects (i.e., IA administration and/or placebo effect), then the real benefit related to HA itself should be, in absolute values, ranging from 0.45 to 1.35 points on 10-NRS WOMAC pain subscore. Such a difference can be considered as not clinically relevant. The main concern with WOMAC variations over time and MCII is that both are closely dependent on baseline values. A 3-point decrease does not have the same clinical impact on patients with WOMAC pain of 9 and 5. Conversely a 50% decrease of pain is likely to be more easily obtained when baseline value is 4 (−2 points) rather than 8 (−4 points). Similarly, a patient’s evaluation of his or her pain and disability at a given time (here 6 months after injection) gives a diametrically opposed vision, since there are assessed without taking into account the previous clinical status. This is the difference between “I am getting well” and “I am getting better.” In our cohort, about 80% of patients who reached the PASS+ threshold were satisfied with viscosupplementation and considered it effective for alleviating their symptoms. A similar percentage of satisfaction (78%) was reported in a cohort of patients retrospectively questioned 6 months after 3 weekly hylan GF-20 injections for knee OA.36 For this reason, PASS can be considered as the most reliable and simple PRO for decision of retreatment with HA, as advised by the experts of the European Viscosupplementation Consensus Group.39 However, despite PASS and satisfaction being highly correlated some patients fulfilling PASS+ definition were not fully satisfied whereas others who did not were satisfied, probably because the threshold of 4/10 was not sufficiently discriminant. Indeed, when using a threshold of 3/10 for PGAP, 100% of patients who reached it were satisfied.

A second important issue to be considered is the excellent benefit/risk ratio that may influence patient’s satisfaction. The effect size, usually used in meta-analyses to compare interventions, is ranked out of context as “small,” “medium,” and “large.” However, the effectiveness of a particular intervention must be interpreted in relation to other interventions that seek to produce the same effect (i.e., NSAIDS, acetaminophen, tramadol, IA corticosteroids). If an intervention gives a moderate clinical improvement with effect size of even as low as 0.37 while being absolutely safe and moderately expensive, this could be considered as a very significant improvement.10 This effect is amplified if it is reproduced in a large majority of patients and even more so if the effects are cumulative over time40,41 as seen with viscosupplementation. In our cohort, the safety and efficacy of the treatment is established by an overall satisfaction rate of 80%, with an average decrease of pain over 6 months by about 50% with only 6% transient and minor local AEs.

The main strength of the present work is that the data are obtained from daily practice conditions and represent results in “real-life setting” using the same assessment tools as in interventional trials. There was no clinical or radiological inclusion/exclusion criterion and all patients were assessed at both baseline and 6 (±1.5) months. Our study has of course several limitations. As it was not an interventional trial, patients could take concomitant NSAIDs, analgesics, SYSADOA as well as all recommended nonpharmacological therapies for OA. We could not assess this multimodal influence on pain and function changes. However, the study showed that a majority of patients reduced the use of analgesics confirming previous data.37,42 The sample size is limited and this might explain the lack of relationship between radiographic features and clinical response as has been demonstrated recently.43 Another limitation is the homogeneity of the study patients. We excluded patients with very severe disease, those with major risk factors of treatment failure and those with failure of a previous viscosupplementation thus introducing a selection bias. This was intentional to provide a real-life sample cohort. As recommended, in our rheumatology department, patients with Kellgren grade IV OA, obesity, large knee effusion or major joint malalignment, and those waiting for knee replacement were not eligible for viscosupplementation. This may explain the relatively low level of WOMAC scores at baseline, the lack of correlation between clinical response and Kellgren grade, and the high percentage of patients who reached the PASS+ definition. Finally, a further limitation is that the choice of a single viscosupplement might limit the extrapolation of our results to other HA products.44

In summary, the present retrospective analysis of data, prospectively recorded in daily practice conditions, suggests that the choice of the PROs influences the interpretation of the effectiveness of viscosupplementation. Our data showed that all the studied PROs are valuable assessment tools but that PASS PGAP is that which correlates the best with patients’ level of satisfaction. The effectiveness appears better when a state-attainment criterion such as PASS, which represents the patient’s perception at a given time, than when the decrease of WOMAC score is used. Health authorities and guideline developers should take this in consideration while decision making and be cautious in not to recommend and lose therapeutic options that may benefit a significant number of patients in a chronic and debilitating pathology in which few effective and safe treatments are available.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments and Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Thierry Conrozier has received honorarium from Aptissen, Bioventus, Expanscience, Labrha and Sanofi for expert, speaker, and consultant services. Raghu Raman has received honorarium from Sanofi, Labrha, CeramTec, Peter Brehm, Join Replacement Industry and Aesculap for consultant services.

Informed Consent: Verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval for this study was waived by Hôpital Nord Franche-Comté because the study was a retrospective analysis of data obtained in daily practice conditions.

Trial Registration: Not applicable.

References

- 1. Wang X, Wang Y, Bennell KL, Wrigley TV, Cicuttini FM, Fortin K, et al. Cartilage morphology at 2-3 years following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with or without concomitant meniscal pathology. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:426-36. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3831-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O’Neill T, Jinks C, Ong BN. Decision-making regarding total knee replacement surgery: a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, Bannwarth B, Bijlsma JW, Dieppe P, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials [ESCISIT]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1145-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:465-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22:363-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bruyère O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP, Branco J, Luisa Brandi M, Guillemin F, et al. An algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis in Europe and internationally: a report from a task force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44:253-63. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bannuru RR, Schmid CH, Kent DM, Vaysbrot EE, Wong JB, McAlindon TE. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:46-54. doi: 10.7326/M14-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bannuru RR, Natov NS, Obadan IE, Price LL, Schmid CH, McAlindon TE. Therapeutic trajectory of hyaluronic acid versus corticosteroids in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1704-11. doi: 10.1002/art.24925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Posnett J, Dixit S, Oppenheimer B, Kili S, Mehin N. Patient preference and willingness to pay for knee osteoarthritis treatments. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:733-44. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S84251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rutjes AW, Jüni P, da Costa BR, Trelle S, Nüesch E, Reichenbach S. Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:180-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Campbell KA, Erickson BJ, Saltzman BM, Mascarenhas R, Bach BR, Jr, Cole BJ, et al. Is local viscosupplementation injection clinically superior to other therapies in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:2036-45.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Trojian TH, Concoff AL, Joy SM, Hatzenbuehler JR, Saulsberry WJ, Coleman CI. AMSSM scientific statement concerning viscosupplementation injections for knee osteoarthritis: importance for individual patient outcomes. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:84-92. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jevsevar D, Donnelly P, Brown GA, Cummins DS. Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review of the evidence. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:2047-60. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miller LE, Block JE. US-approved intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections are safe and effective in patients with knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized saline-controlled trials. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord 2013;6:57-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jevsevar DS. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd edition. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:571-6. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-09-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tubach F, Ravaud P, Baron G, Falissard B, Logeart I, Bellamy N, et al. Evaluation of clinically relevant changes in patient reported outcomes in knee and hip osteoarthritis: the minimal clinically important improvement. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:29-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bannuru RR, Vaysbrot EE, McIntyre LF. Did the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons osteoarthritis guidelines miss the mark? Arthroscopy. 2014;30:86-9. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lequesne MG. The algofunctional indices for hip and knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:779-81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pham T, Van Der Heijde D, Lassere M, Altman RD, Anderson JJ, Bellamy N, et al. Outcome variables for osteoarthritis clinical trials: The OMERACT-OARSI set of responder criteria. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1648-54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, Ekdahl C, Beynnon BD. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score [KOOS]—development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28:88-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Golightly YM, Allen KD, Nyrop KA, Nelson AE, Callahan LF, Jordan JM. Patient-reported outcomes to initiate a provider-patient dialog for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:123-31. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Migliore A, Bizzi E, Herrero-Beaumont J, Petrella RJ, Raman R, Chevalier X. The discrepancy between recommendations and clinical practice for viscosupplementation in osteoarthritis: mind the gap! Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:1124-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mills S, Torrance N, Smith BH. Identification and management of chronic pain in primary care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18:22. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0659-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sofat N, Ejindu V, Kiely P. What makes osteoarthritis painful? The evidence for local and central pain processing. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:2157-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. International Association for the Study of Pain. IASP taxonomy. http://www.iasp-pain.org/Taxonomy.

- 27. Tubach F, Dougados M, Falissard B, Baron G, Logeart I, Ravaud P. Feeling good rather than feeling better matters more to patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:526-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tubach F, Ravaud P, Baron G, Falissard B, Logeart I, Bellamy N, et al. Evaluation of clinically relevant states in patient reported outcomes in knee and hip osteoarthritis: the patient acceptable symptom state. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:34-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tubach F, Ravaud P, Martin-Mola E, Awada H, Bellamy N, Bombardier C, et al. Minimum clinically important improvement and patient acceptable symptom state in pain and function in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, chronic back pain, hand osteoarthritis, and hip and knee osteoarthritis: results from a prospective multinational study. Arthritis Care Res [Hoboken]. 2012;64:1699-707. doi: 10.1002/acr.21747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bellamy N, Hochberg M, Tubach F, Martin-Mola E, Awada H, Bombardier C, et al. Development of multinational definitions of minimal clinically important improvement and patient acceptable symptomatic state in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res [Hoboken]. 2015;67:972-80. doi: 10.1002/acr.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Perrot S, Bertin P. ‘Feeling better’ or ‘feeling well’ in usual care of hip and knee osteoarthritis pain: determination of cutoff points for patient acceptable symptom state [PASS] and minimal clinically important improvement [MCII] at rest and on movement in a national multicenter cohort study of 2414 patients with painful osteoarthritis. Pain. 2013;154:248-56. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cooper C, Rannou F, Richette P, Bruyère O, Al-Daghri N, Altman RD, et al. Use of intra-articular hyaluronic acid in the management of knee osteoarthritis in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). Epub 2017. January 24. doi: 10.1002/acr.23204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteoarthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494-501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Altman RD, Gold GE. Radiographic atlas for osteoarthritis of the hand, hip and knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2007;15(Suppl A):A1-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Conrozier T, Patarin J, Mathieu P, Rinaudo M. Steroids, lidocain and ioxaglic acid modify the viscosity of hyaluronic acid: in vitro study and clinical implications. Springerplus. 2016;5:170. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-1762-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Conrozier T, Mathieu P, Schott AM, Laurent I, Hajri T, Crozes P, et al. Factors predicting long-term efficacy of Hylan GF-20 viscosupplementation in knee osteoarthritis. J Bone Spine. 2003;70:128-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Conrozier T, Eymard F, Afif N, Balblanc JC, Legré-Boyer V, Chevalier X; Happyvisc Study Group. Safety and efficacy of intra-articular injections of a combination of hyaluronic acid and mannitol [HAnOX-M] in patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: results of a double-blind, controlled, multicenter, randomized trial. Knee. 2016;23:842-8. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zou K, Wong J, Abdullah N, Chen X, Smith T, Doherty M, et al. Examination of overall treatment effect and the proportion attributable to contextual effect in osteoarthritis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1964-70. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Raman R, Henrotin Y, Chevalier X, Migliore A, Jerosch J, Monfort J, et al. Decision algorithms for the retreatment with viscosupplementation in patients suffering from knee osteoarthritis. recommendations from the European Viscosupplementation Consensus group (EUROVISCO). Cartilage. Epub 2017. February 1. doi: 10.1177/1947603517693043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Navarro-Sarabia F, Coronel P, Collantes E, Navarro FJ, de la Serna AR, Naranjo A, et al. AMELIA Study Group. A 40-month multicentre, randomised placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and carry-over effect of repeated intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid in knee osteoarthritis: the AMELIA project. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1957-62. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.152017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Altman RD, Rosen JE, Bloch DA, Hatoum HT. Safety and efficacy of retreatment with a bioengineered hyaluronate for painful osteoarthritis of the knee: results of the open-label Extension Study of the FLEXX Trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:1169-75. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Conrozier T, Bozgan AM, Bossert M, Sondag M, Lohse-Walliser A, Balblanc JC. Standardized follow-up of patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis treated with a single intra-articular injection of a combination of cross-linked hyaluronic acid and mannitol. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;9:175-9. doi: 10.4137/CMAMD.S39432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Eymard F, Chevalier X, Conrozier T. Obesity and radiological severity are associated with viscosupplementation failure in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. Epub 2017. January 27. doi: 10.1002/jor.23529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Henrotin Y, Raman R, Richette P, Bard H, Jerosch J, Conrozier T, et al. Consensus statement on viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid for the management of osteoarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:140-9. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]