Abstract

Objective

Osteoarthritis (OA) is induced by accumulated mechanical stress to joints; however, little has been reported regarding the cause among detailed mechanical stress on cartilage degeneration. This study investigated the influence of the control of abnormal joint movement induced by anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury in the articular cartilage.

Design

The animals were divided into 3 experimental groups: CAJM group (n = 22: controlling abnormal joint movement), ACL-T group (n = 22: ACL transection or knee anterior instability increased), and INTACT group (n = 12: no surgery). After 2 and 4 weeks, the knees were harvested for digital microscopic observation, soft X-ray analysis, histological analysis, and synovial membrane molecular evaluation.

Results

The 4-week OARSI scores showed that cartilage degeneration was significantly inhibited in the CAJM group as compared with the ACL-T group (P < 0.001). At 4 weeks, the osteophyte formation had also significantly increased in the ACL-T group (P < 0.001). These results reflected the microscopic scoring and soft X-ray analysis findings at 4 weeks. Real-time synovial membrane polymerase chain reaction analysis for evaluation of the osteophyte formation–associated factors showed that the mRNA expression of BMP-2 and VEGF in the ACL-T group had significantly increased after 2 weeks.

Conclusions

Typically, abnormal mechanical stress induces osteophyte formation; however, our results demonstrated that CAJM group inhibited osteophyte formation. Therefore, controlling abnormal joint movement may be a beneficial precautionary measure for OA progression in the future.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, articular cartilage, osteophyte, animal model

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a type of joint disease that results from cartilage degradation and osteophyte formation in joints, and believed to be caused by accumulated mechanical stress.1 Generally, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) transection model is widely used to elucidation for a mechanism of OA progression.2,3 ACL transection promotes abnormal joint motion, such as anterior translation of tibia, and the abnormal mechanical stress may develop between the femur and tibia cartilage.

In our previous studies, to establish abnormal joint motion of the tibia and its controlled effect, we created a controlled abnormal joint movement (CAJM) model to restore the biomechanical function following ACL transection through a nylon suture placed on the outer aspect of the knee joint.4 Using the CAJM model, we reported the controlled abnormal joint movement suppress inflammatory cytokines may help delay the progression of OA.5

Other studies indicated that anterior translation of the tibia induced by ACL injury was related to osteophyte formation.6-8 Anterior translation of the tibia causes abnormal joint mechanics by changes in contact stress. This change in contact stress results in an increase to various growth factors during osteophyte progression in the knee. In particular, the synovial membrane exhibits increased transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which play an initial and terminal role in differentiation.9-11 Although symptoms are not always present, various growth factors are expressed during the progression of osteophytes in the knees of patients with OA, and osteophytes are understood to be a result of abnormal mechanical stress.

We hypothesized that the abnormal joint movement is probably more from increased contact stresses on the joint, which the bone osteocytes will sense via Wolff’s law, and then the bone “senses” that it needs to “grow” osteophytes in order to limit the abnormal movement. The objective this study was to evaluate osteophyte formation and cartilage degeneration on controlled abnormal joint movement using histological and molecular biological analyses. These findings may help to understand the progression of OA and to provide new prevention methods for patients with OA.

Material and Methods

Animals and Experimental Design

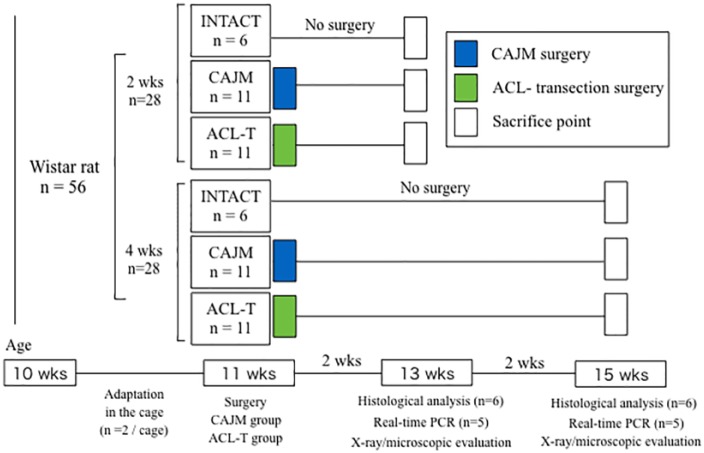

All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Saitama Prefectural University (approval number: 27-9). A new protocol was devised according to the “Animal Research: Reporting of in Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE)” guidelines.12 A total of 56 ten-week-old Wistar rats (Sankyo Labo Service Corp., Tokyo, Japan) were obtained for use in this study ( Fig. 1 ). The animals were divided into 3 experimental groups: an intact group (INTACT, n = 12: the rats did not undergo any surgery), a CAJM group (CAJM, n = 22: external support was provided to decrease anterior translation after complete ACL transection), and an ACL transection group (ACL-T, n = 22: bone tunnel with complete ACL transection, anterior translation increased). All rats were housed and maintained on a 12-hour light-dark cycle at a constant temperature of 23°C, with free access to food and tap water.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating experimental protocol.

Surgical Procedures

As described previously,4,5,13 the ACL-T and CAJM models were established after anesthetization of the rats with pentobarbital (0.8 mL/kg) (Supplementary methods). The medial capsule of the right knee joint was exposed without disrupting the patellar tendon, and the ACL was completely transected. Both models were established by creating a bone tunnel along the anterior aspect of the proximal tibia. In the ACL-T group, the skin was closed with a nylon suture and was disinfected. In the CAJM group, a nylon thread was passed through the bone tunnel and was tied to the posterior aspect of the distal femur. A reduction in abnormal joint movements was achieved without intra-articular suturing of the ligament.

Functional Recovery and Anterior Translation Examination

The postoperative recovery of motor function was evaluated by placing rats randomly selected from different groups onto an accelerating rotarod (Muromachi Kikai Co., Tokyo, Japan) for rotarod analysis. To rule out differences in learning skills between the 3 groups of rats, each group was assessed over 3 trials (the rotation speed was adjusted to 10 rotations per minute). The motor function of each animal was determined by averaging the scores of 3 trials.

At 2 and 4 weeks, 6 rats from each group (n = 36) were sacrificed following anesthetization with pentobarbital, and their right lower limbs were examined radiographically. The femur was subjected to examination systems,5 and the anterior translation of the tibia was evaluated with anterior traction using a 0.2 kgf constant force spring (Sunco Spring Corp., Kanagawa, Japan). Radiographs were captured with a soft radiogram M-60 (Softex Corp., Kanagawa, Japan). X-ray radiography was performed at 28 kV and 1 mA for 1.5 seconds, and images were captured with a NAOMI digital X-ray sensor (RF Corp., Nagano, Japan). Digital images were used to quantify the anterior displacement relative to control rats under normal conditions using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Osteophyte Scoring from Radiographic Examination

To evaluate the changes in OA, the rats were positioned with their knee flexed at 90°. Following scanning, the osteophyte score was evaluated based on a previous study14 (Supplemental Table 1). The scoring comprised osteophyte, cyst, joint space, and sclerosis measurements.

Histological Analysis

The rat knees were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 48 hours and were decalcified in a Super Decalcifier I solution (Polysciences Inc., Taipei, Taiwan) for 24 hours. They were subsequently washed with phosphate-buffered saline and were embedded in an optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetek Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The specimens were cut 16 μm from the tibial plateau and femur on the frontal plane. Sections were stained with safranin-O/fast green staining and alizarin red/Alcian blue staining, and were rated according to the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) scoring system for cartilage.15 Every 3 sections of the 4 areas (i.e., the medial tibia, lateral tibia, medial femur, and lateral femur) were evaluated according to previously reported methods.16 This scoring system consists of 2 subcategories: the grade (6 points) and the stage (4 points). The total OARSI scores were calculated as the “grade × stage.” A total score of 24 indicated severe OA, while a score of 0 indicated a normal joint. Four areas per section calculated the summed total score (0 to 96). According to a previous study,17 the osteophytes were evaluated semiquantitatively using osteophyte formation scores consisting of 2 dimensions: the size and maturity (Supplemental Table 2). Four areas per section (i.e., the medial tibia, lateral tibia, medial femur, and lateral femur) were evaluated to calculate the summed total score (0 to 24).

Microscopic Examination

Five knee joints were harvested from each of the CAJM and ACL-T groups (n = 20) at 2 and 4 weeks after the surgery, and the samples were carefully separated from the tibia and femur. The contralateral articular cartilage (left side) of the ACL-T group was used for INTACT. The tibia and femur were stained with Indian ink to visualize the damaged region. Microscopic pictures of the femur and tibia were captured with a digital microscopic system (Keyence, Tokyo, Japan). Based on a previous study,18 the cartilage degeneration of the femur and the tibial surface was evaluated through macroscopic scoring on a scale of 0 to 5 points (Supplemental Table 3).

Quantitative mRNA Expression

The TGF-β, BMP-2, and VEGF mRNA expression levels associated with bone marrow progression in the synovial membranes were evaluated with a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) 2 weeks and 4 weeks after the surgery in the CAJM and ACL-T groups. The contralateral articular cartilage (left side) of the ACL-T group was used for standardization (normal tissue samples). The synovial membranes were isolated and immersed in an RNA-stabilizing solution (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). The total RNA was extracted with an RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The synthesis of the cDNA was conducted with a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). A real-time PCR was performed with a StepOne-Plus real-time system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using 2 μL of cDNA in the presence of the appropriate primers (TaqMan primers, NE, USA): BMP-2, TGF-β, and VEGF (Table 1). The relative expression levels of the genes were normalized to a housekeeping gene (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GAPDH) using the 2−ΔΔCt method to calculate the relative levels of mRNA expression.

Table 1.

Gene Expression Assays Used for Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).

| Primer used in Real-Time PCR | |

|---|---|

| Gene | Assay Number |

| BMP-2 | Rn00567818_m1 |

| TGF-β | Rn00572010_m1 |

| VEGF | Rn01511602_m1 |

| GAPDH | Rn01775763_g1 |

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 21.0 software (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The normality of the value distribution for each variable was evaluated with a Shapiro-Wilk test. A parametric statistical analysis of the 3 groups was performed with a 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Tukey post hoc analysis. A nonparametric statistical analysis was performed with a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a Mann-Whitney U test for pairwise differences. The resulting P values were compared with Bonferroni’s corrected value (P = 0.017), which was calculated based on the number of pairwise comparisons made. To compare the 2 groups, a parametric statistical analysis was performed with the Student t test. A nonparametric statistical analysis was performed with the Mann-Whitney U test. Moreover, the correlation coefficient between the anterior translation and scores were calculated. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

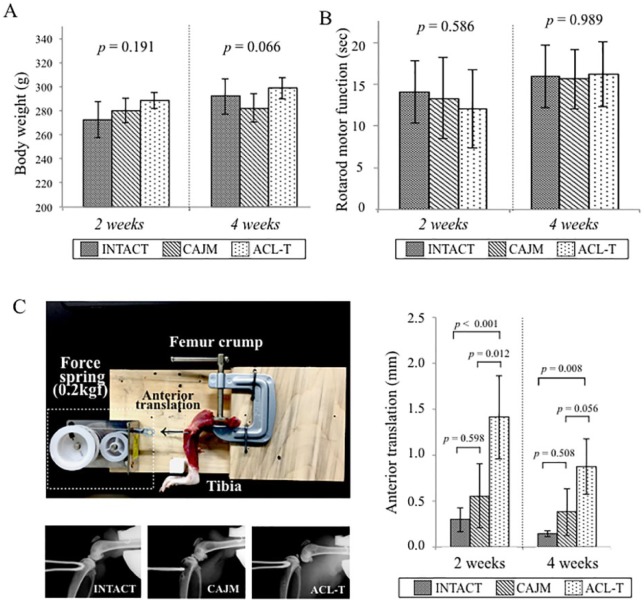

There were no significant changes in the weight of the normal rats 2 weeks after surgery (P = 0.191 with ANOVA; INTACT, 273 [252-293] g; CAJM, 279 [269-290] g; ACL-T, 287 [278-297] g) and 4 weeks after surgery: (P = 0.066 with ANOVA; INTACT, 297 [277-316] g; CAJM, 282 [271-292] g; ACL-T, 299 [287-310] g) ( Fig. 2A ). The evaluation through the rotarod test after surgery demonstrated that the results did not differ between the 3 groups at 2 weeks (P = 0.586 with ANOVA; INTACT, 14.1 [10.4-17.8] seconds; CAJM, 13.3 [8.5-18.2] seconds; ACL-T, 12.1 [7.4-16.7] seconds) and 4 weeks (P = 0.989 with ANOVA; INTACT, 15.3 [12.3-19.6] seconds; CAJM, 15.6 [12.1-19.2] seconds; ACL-T, 16.9 [12.3-20.1] seconds) after surgery ( Fig. 2B ).

Figure 2.

Verification of the CAJM (controlling abnormal joint movement) model (weight, motor function, and anterior translation of tibia). (A) Change of body weight at each point. There was no different among 3 groups at 2 weeks (P = 0.191 with analysis of variance [ANOVA]) and 4 weeks (P = 0.066 with ANOVA). (B) Motor function evaluation using rotarod analysis at each point. There was no different among 3 groups at 2 weeks (P = 0.586 with ANOVA) and 4 weeks (P = 0.989 with ANOVA). (C) Anterior translation evaluation method and results. A custom knee instability evaluation system was used to quantify the anterior laxity. The femur was held with a manual clamp, and the tibia was retracted forward by a 0.2 kgf constant force spring. A soft X-ray radiography was used to evaluate the anterior translation, and the displacement was calculated. At 2 weeks, the degree of anterior translation was significantly increased in the ACL-T (anterior cruciate ligament transection) group as compared with that in the CAJM group (P < 0.001 with post hoc Tukey method). At 4 weeks, the ACL-T group showed significantly increased anterior translation as compared with that in the INTACT (no surgery) group (P = 0.008 with post hoc Tukey method). All data are expressed as means with 95% confidence interval limits. The exact P-values between the compared groups (based on a 1-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test) are displayed on the graph.

To evaluate the anterior translation after surgery, an X-ray was performed with our original anterior joint instability measurement system at 2 and 4 weeks. At 2 weeks, the anterior translation of the CAJM group had significantly decreased relative to the ACL-T group (INTACT, 0.301 [0.165-0.427] mm; CAJM, 0.556 [0.205-0.907] mm; ACL-T, 1.414 [0.959-1.868] mm). The anterior translation had also increased in the ACL-T group at 4 weeks (INTACT, 0.144 [0.114-0.173] mm; CAJM, 0.379 [0.122-0.636] mm; ACL-T, 0.876 [0.573-1.179] mm). Exact P values are given in Figure 2C .

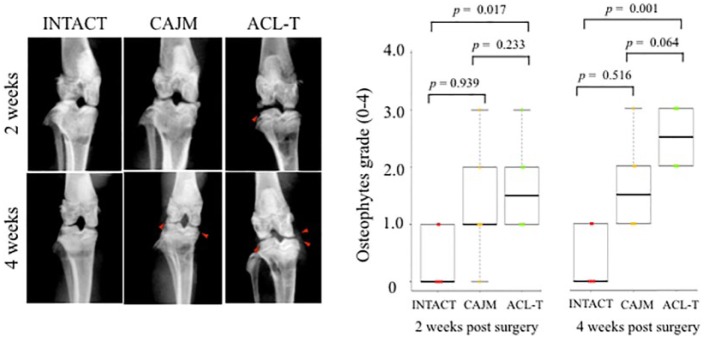

Osteophyte Scoring Using Radiographic Examination

To evaluate the knee OA, soft X-ray digital scanning was performed at 2 and 4 weeks, respectively, and was graded with Oprenyeszk’s score18 ( Fig. 3 ). At 2 weeks, the scores of the ACL-T groups were significantly higher than those of the INTACT groups (INTACT, 0 [0-1]; CAJM, 1 [1-2]; ACL-T, 1.5 [1-2]); however, no significant differences were detected between the CAJM and ACL-T groups (P = 0.233 with post hoc Mann-Whitney U test; Bonferroni correction). At 4 weeks, the scores of the ACL-T groups were significantly lower than those of the CAJM and INTACT groups (INTACT, 0 [0-1]; CAJM, 1 [1-2]; ACL-T, 2.5 [2-3]). No significant differences were noted between the CAJM and ACL-T groups (P = 0.064 with post hoc Mann-Whitney U test; Bonferroni correction).

Figure 3.

Knee osteophyte formation evaluation with radiography. Time course of soft X-ray radiography of knee joints in INTACT (no surgery), CAJM (controlling abnormal joint movement), and ACL-T (anterior cruciate ligament transection) groups at 2 and 4 weeks. Both the ACL-T and CAJM groups showed osteophyte formation (red triangle). The radiographic images were graded, and the ACL-T group scored higher than the INTACT group at 2 weeks (P = 0.017 with post hoc Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction) and 4 weeks (P = 0.001 with post hoc Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction), respectively. The data are expressed as the median at 25% and 75%. The exact P values between the compared groups (based on the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Mann-Whitney U test for pairwise difference) are shown on the graph.

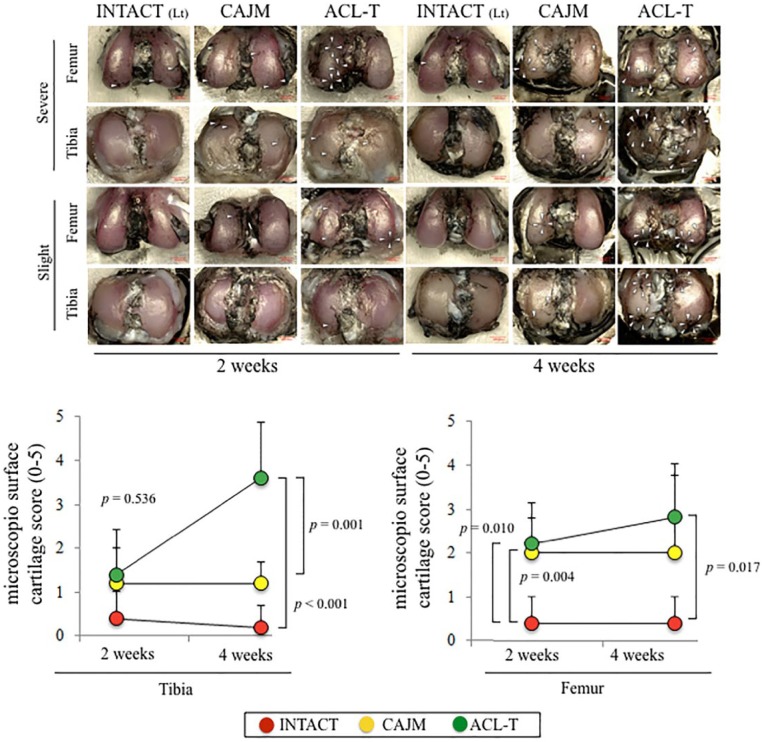

Microscopic Examination

The articular cartilage was graded according to the degeneration progression in the tibia and femur based on a macroscopic examination ( Fig. 4 ). At 2 weeks, in the tibial cartilage, no significant differences were detected among the 3 groups (P = 0.536 with ANOVA; INTACT, 0.4 [0.0-1.0]; CAJM, 1.2 [0.0-2.2]; ACL-T, 1.4 [0.8-2.0]). At 4 weeks, the ACL-T group had higher tibia scores than the CAJM group and the INTACT group (INTACT, 0.2 [0.0-0.7]; CAJM, 1.2 [0.7-1.6]; ACL-T, 3.6 [2.3-4.9]). In comparison with the INTACT group, the femoral cartilage was significantly increased in the CAJM and ACL-T groups at 2 weeks (INTACT, 0.4 [0.0-1.0]; CAJM, 2.0 [1.2-2.6]; ACL-T, 2.2 [1.3-3.1]) and 4 weeks (INTACT, 0.4 [0.0-1.0]; CAJM, 2.0 [0.2-3.4]; ACL-T, 2.8 [1.6-4.0]).

Figure 4.

Macroscopic analysis of tibial and femoral cartilage. Representative imaging of Indian ink staining. The most severe change and slightest change in each group were selected. The white arrow heads indicate the cartilage degeneration point and area. Semiquantification of microscopic features with analysis based on previous scoring systems. The data are expressed as means with lower and upper 95% confidence interval limits. The exact P values between the compared groups (based on a 1-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s post hoc test) are shown on the graph.

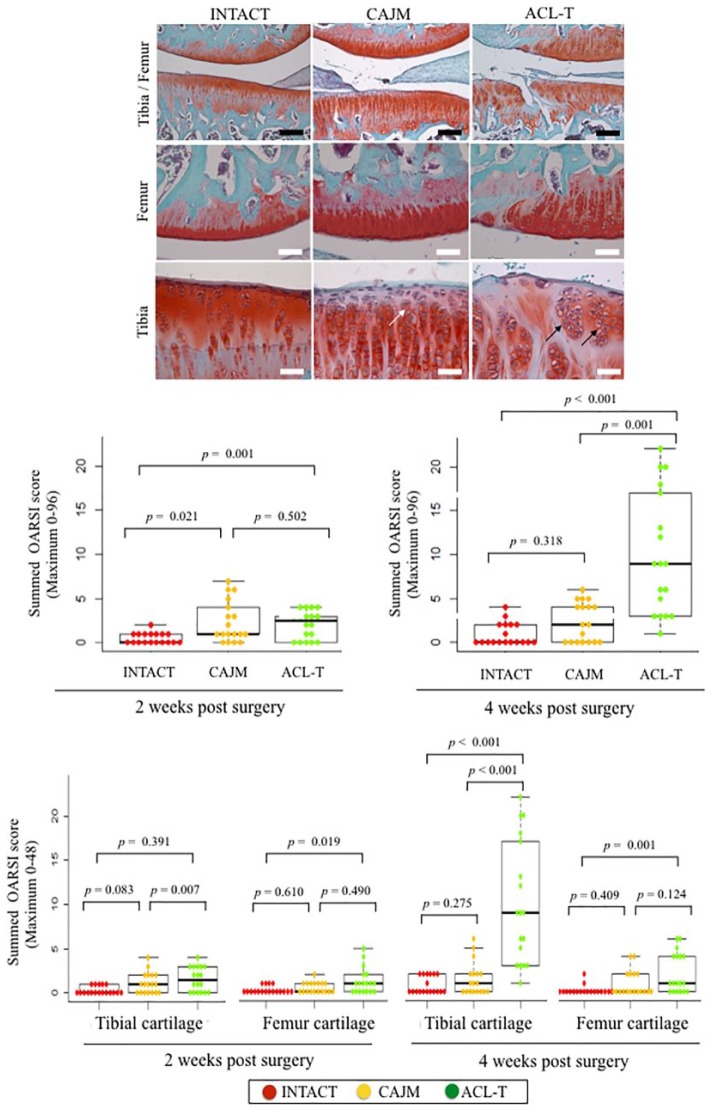

Histological Analysis of Cartilage Degeneration

Histological characteristics at 4 weeks are presented in Figure 5 . The CAJM group exhibited enlargement of the cartilage lacuna and increased the number of chondrocytes. Moreover, the ACL-T group exhibited a confirmed cluster of chondrocytes and surface fibrillation.

Figure 5.

Specific histological findings of articular cartilage at 4 weeks, and OARSI (Osteoarthritis Research Society International) scoring at 2 and 4 weeks. Cartilage sections with safranin O and fast green staining in the INTACT (no surgery), CAJM (controlling abnormal joint movement), and ACL-T (anterior cruciate ligament transection) groups. The CAJM group exhibited enlargement of the cartilage lacuna and increased chondrocytes (white arrow), whereas the ACL-T group exhibited a confirmed cluster of chondrocytes (block arrow) and surface fibrillation. OARSI scores at 2 and 4 weeks. At 2 weeks, the INTACT group’s “Summed OARSI” scores were significantly maintained as compared with those of the CAJM group (P = 0.021 with post hoc Mann Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction) and ACL-T group (P = 0.001 with post hoc Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction). At 4 weeks, the ACL-T group showed a significantly increased OARSI score (Summed OARSI) as compared with that of the INTACT group (P < 0.001 with post hoc Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction) and of the CAJM group (P < 0.001 with post hoc Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction). The exact P values between the compared groups (based on the Kruskal-Wallis test with the Mann-Whitney U test) are shown on the graph.

To evaluate the articular cartilage at 2 and 4 weeks, the latter was graded based on the OARSI histological scoring system ( Fig. 5 ). At 2 weeks, the total OARSI score was significantly higher in the ACL-T group and CAJM group than in the INTACT groups (INTACT, 0 [0-1]; CAJM, 1 [1-4]; ACL-T, 2.5 [0-3]). However, there were no differences between the CAJM and ACL-T groups (P = 0.502, with post hoc Mann-Whitney U test; Bonferroni correction). At 4 weeks, the total OARSI score was significantly higher in the ACL-T group than in the CAJM and INTACT groups (INTACT, 0 [0-2]; CAJM, 2 [0-4]; ACL-T, 9 [3-17]). Exact P values are given in Figure 5 .

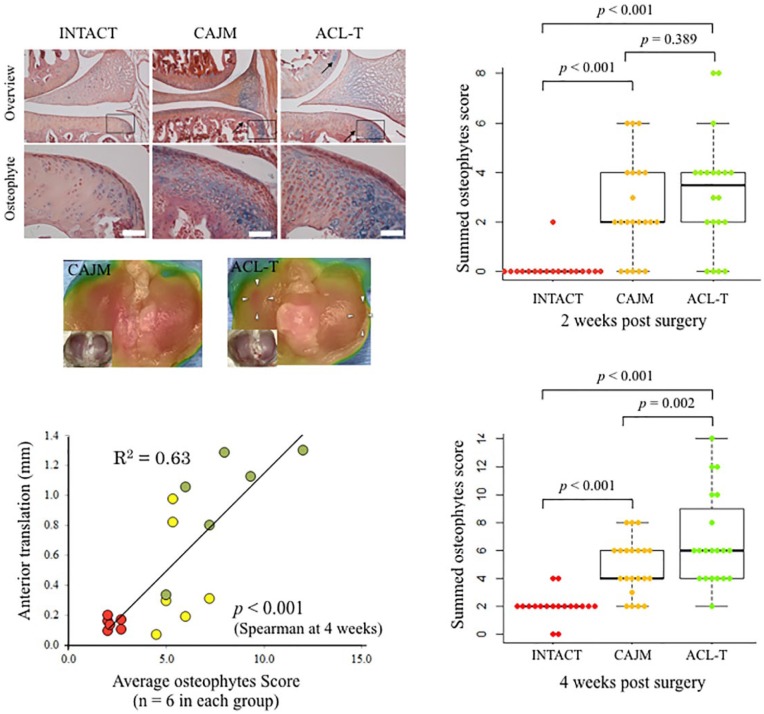

Histological Analysis of Osteophyte Formation

The total osteophyte formation score was significantly higher in the ACL-T group and CAJM group than in the INTACT groups (INTACT, 0 [0-9]; CAJM, 2 [0-4]; ACL-T, 3 [2-4]) at 2 weeks. However, there were no differences between the CAJM and ACL-T groups (P = 0.389, with post hoc Mann-Whitney U test; Bonferroni correction). The scores at 4 weeks were significantly higher in the ACL-T group than in the CAJM group or the INTACT group (INTACT, 2 [2-2]; CAJM, 4 [3-6]; ACL-T, 6 [4-6]). Moreover, the correlation coefficient between the anterior translation weight and score were significant (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.63). Exact P values are given in Figure 6 .

Figure 6.

Histological findings of osteophyte formation at 4 weeks, and osteophyte scoring at 2 and 4 weeks. Cartilage sections with alizarin-red/Alcian-blue staining in the INTACT (no surgery), CAJM (controlling abnormal joint movement), and ACL-T (anterior cruciate ligament transection) groups. The CAJM and ACL-T groups exhibited confirmed osteophyte formation. Osteophyte scoring at 2 and 4 weeks. At 2 weeks, the scores were higher in the CAJM and ACL-T groups than in the INTACT group (both group, P < 0.001 with post hoc Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction). At 4 weeks, the ACL-T group exhibited significantly higher scores than the INTACT and CAJM groups (INTACT vs. ACL-T, P < 0.001; CAJM vs. ACL-T, P = 0.002, with post hoc Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction). The correlation coefficient between the front drawer weight and score were significant (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.63). The exact P values between the compared groups (based on the Kruskal-Wallis test with the Mann-Whitney U test) are shown on the graph.

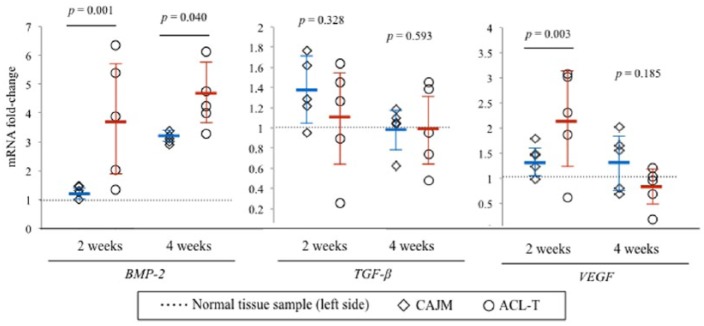

mRNA Expression Levels in Synovial Membranes

The synovial membrane of the rats in the CAJM and ACL-T groups was harvested 2 and 4 weeks after the surgery. A real-time PCR was used to assess the alterations in the expression levels of the genes associated with osteophyte progression, and the changes in the CAJM and ACL-T groups were compared with the expression levels of the normal tissues (i.e., normal tissue samples harvested from the opposite knee) at the baseline. As shown in Figure 7 , at 2 weeks, the BMP-2, TGF-β, and VEGF mRNA expression levels were approximately 3.80-fold, 1.01-fold, and 2.18-fold higher in the ACL-T group, and 1.29-fold, 1.37-fold, and 1.40-fold higher in the CAJM group, respectively. The mRNA expression levels of BMP-2 and VEGF in the ACL-T group were aberrantly significantly upregulated as compared with those in the CAJM group. The BMP-2, TGF-β, and VEGF mRNA expression levels were approximately 4.46-fold, 1.00-fold, and 0.81-fold higher in the ACL-T group, and 3.11-fold, 1.00-fold, and 1.33-fold higher in the CAJM group, respectively. The mRNA expression levels of the BMP-2 and VEGF in the CAJM group were aberrantly significantly upregulated as compared with those in the ACL-T group.

Figure 7.

mRNA expression levels in the synovial membrane. Synovial membrane tissue samples harvested at the 2- and 4-week time points were evaluated to investigate the mRNA expression of factors associated with osteophyte formation as a proportion of the normal tissue samples (ratio: 1.0). At 2 weeks, the mRNA expression levels of the BMP-2 (bone morphogenetic protein–2) had significantly increased in the ACL-T (anterior cruciate ligament transection) group as compared with those in the CAJM (controlling abnormal joint movement) group (P = 0.001 based on post hoc Mann-Whitney U test). The VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) mRNA expression was also significantly increased in the ACL-T group (P = 0.003 based on post hoc Mann-Whitney U test). At 4 weeks, the BMP-2 mRNA expression was significantly increased in the CAJM group. The data are expressed as the fold change with 95% confidence interval limits.

Discussion

Based on a previous study,4,5,13 the present study used the CAJM model to understand the relationship of abnormal joint movements to the progression of articular cartilage degeneration and osteophyte formation. This model used a nylon suture to induce normal joint movement. As a result, the histological data indicated that the CAJM model significantly decreased cartilage degeneration and limited osteophyte formation and certain mRNA expressions according to osteophyte growth factors in the synovial membrane.

The abnormal joint motion caused by knee injury is a predominant factor in OA progression.19 In animal models, abnormal joint movement, such as joint instability, leads to long-term alterations of the knee articular cartilage, as evidenced in mouse,3,6,20 rat,5,13 and rabbit models.2,21 In particular, in rabbit model, the degree of anterior translation induced by ACL transection model was associated with degeneration of the articular cartilage.2 Our model was designed to induce a biomechanical change, such as anterior translation, with nylon sutures. The results demonstrated different anterior translation between the ACL-T and CAJM models at 2 and 4 weeks, and the CAJM model inhibited the degeneration of the articular cartilage more than the ACL-T model. These findings indicated that the control of anterior joint instability had a beneficial effect on the articular cartilage, our model has obtained an analogous result to the previous research.

On the other hand, osteophytes are small spurs that form in and around the knee joint as a result of chronic inflammation. Although the mechanism of osteophyte formation in OA remains unclear, the involvement of the synovial membrane in osteophyte formation appeared within 2 weeks of the induction of experimental OA. According to our hypothesis, abnormal anterior translation of the tibia probably results from increased contact stresses on the bone, which the bone osteocytes will sense via Wolff’s law, and then the bone will “sense” that it needs to “grow” osteophytes in order to limit the abnormal motion. In particular, in animal models, anterior translation at a relatively early stage has been reported to reduce the range of motion with osteophytes.7,21 As the present model was a method to reduce abnormal joint movement at an early stage, the formation of osteophytes may have been mild.

In addition, the synovial membrane is an important site of osteophyte formation. The edges of the cartilage, which receive appropriate nutrition from the synovial membrane, induce the formation of osteophytes. Various growth factors are expressed in the osteophytes of experimental models and clinical patients. Both the TGF-β and BMP-2 can induce major osteophytes in murine knee joints. Moreover, in animal models,9-11 newborn blood vessel factors such as the VEGF, VEGF-receptor, vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM), and fibroblast growth factor–2 (FGF-2) also contribute to the growth of osteophytes as they supply nutrition. In the present study, the ACL-T model exhibited osteophyte formation at 4 weeks, and the synovial membrane mRNA expression levels of the BMP-2 and VEGF were increased at the 2- and 4-week time points in the ACLT model. These results indicated that the control of anterior translation inhibited osteophyte formation. Previous research has shown that anterior translation at 4 weeks after surgery was reduced in an ACL transection rat model, as the recovery process for animal models was expedited compared to that for humans.22 Moreover, anterior translation induced by ACL injury requires osteophyte formation, and the range of motion and joint mobility is subsequently reduced.20 Considering these various findings, osteophytes are probably a result of instability and may limit joint motion, but they form as a result of bone growth due to increased contact stress resulting from abnormal joint mechanics. On the other hand, for articular cartilage, the factors associated with osteophyte formation have been shown to induce OA. These abnormal contact stresses play a crucial role in the physiology of various tissues: mechanical signals are critical determinants of tissue morphogenesis and maintenance; however, high-strain mechanotransduction by cartilage mechanical stress is relevant to the pathogenesis of OA. The present results indicate that the control of contact stress resulting from abnormal anterior instability suppressed cartilage degeneration, which was associated with osteophyte formation in the histological and real-time PCR analyses. These findings showed that an appropriate contact stress condition maintained cartilage formation, and restabilization of the joint provided a good mechanical condition for the knee after ACL injury.

In order to interpret and apply the findings of the study properly, its limitations should be acknowledged. First, the experimental period only included the 2- and 4-week points after surgery; the long-term effects of cartilage degeneration and osteophyte formation were not examined. However, one of our previous studies showed that the CAJM model induced lower cartilage degeneration than the ACL-T model 12 weeks after surgery. Therefore, this study focused on controlling abnormal joint movement of the knee in an early stage. Second, the use of an experimental rat model, which implied a small knee joint size, meant that changes in the joint kinematics (including the tibial rotation) following ACL transection could not be accurately evaluated. Although, anterior displacement was measured by the distance between the non-traction condition and the anterior traction condition at each sacrifice time point, the anterior displacement differences at the later postoperative times between the control, CAJM, and ACL-T knees may also be due to changes in the knee soft tissues resulting from the surgical procedures and tissue responses.

In conclusion, this study examined the association between anterior translation and osteophyte formation in the progression of articular cartilage degeneration. It appeared that the control of abnormal joint movement was indeed associated with the inhibition of cartilage degeneration and osteophyte formation, as evidenced with microscopic, histological, and biochemical analyses. However, further research is required to characterize the features of mechanical stress associated with the development of OA and to gather information to guide the development of interventions intended to optimize the cartilage health of the knee joint.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Acknowledgments and Funding: The authors would like to thank Yuki Minegishi (Koseikai Hospital, PT), Daisuke Shimizu (Kasukabe-kose Hospital, PT), Mitsuhiro Kameda (Kasukabe Chuo General Hospital), Namine Kiso, Kanae Mastui, Kaichi Ozone, Shiori Tsukamoto, Yuichiro Oka, Yoko Shirose, and Nozomi Kuwabara (students at Saitama Prefectural University) for their assistance with the surgery and sample collection. The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Sasakawa Scientific Research Grant from The Japan Science Society (28-621).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Saitama Prefectural University (approval number: 27-9).

Animal Welfare: The present study followed international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for humane animal treatment and complied with relevant legislation.

Supplemental Material: The supplemental material for this article is available at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/1947603517700955

References

- 1. Buckwalter JA, Anderson DD, Brown TD, Tochigi Y, Martin JA. The roles of mechanical stresses in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: implications for treatment of joint injuries. Cartilage. 2013;4(4):286-94. doi: 10.1177/1947603513495889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tochigi Y, Vaseenon T, Heiner AD, Fredericks DC, Martin JA, Rudert MJ, et al. Instability dependency of osteoarthritis development in a rabbit model of graded anterior cruciate ligament transection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(7):640-7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kamekura S, Hoshi K, Shimoaka T, Chung U, Chikuda H, Yamada T, et al. Osteoarthritis development in novel experimental mouse models induced by knee joint instability. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(7):632-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kokubun T, Kanemura N, Murata K, Moriyama H, Morita S, Jinno T, et al. Effect of changing the joint kinematics of knees with a ruptured anterior cruciate ligament on the molecular biological responses and spontaneous healing in a rat model. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(11):2900-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murata K, Kanemura N, Kokubun T, Fujino T, Morishita Y, Onitsuka K, et al. Controlling joint instability delays the degeneration of articular cartilage in a rat model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(2):297-308. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hsia AW, Anderson MJ, Heffner MA, Lagmay EP, Zavodovskaya R, Christiansen BA. Osteophyte formation after ACL rupture in mice is associated with joint restabilization and loss of range of motion. J Orthop Res. 2017;35(3):466-73. doi: 10.1002/jor.23252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Kraan PM, van den Berg WB. Osteophytes: relevance and biology. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(3):237-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dayal N, Chang A, Dunlop D, Hayes K, Chang R, Cahue S, et al. The natural history of anteroposterior laxity and its role in knee osteoarthritis progression. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(8):2343-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davidson EB, Vitters EL, Van Der Kraan PM, van den Berg WB. Expression of transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) and the TGFβ signalling molecule SMAD-2P in spontaneous and instability-induced osteoarthritis: role in cartilage degradation, chondrogenesis and osteophyte formation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1414-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kaneko H, Ishijima M, Futami I, Tomikawa N, Kosaki K, Sadatsuki R, et al. Synovial perlecan is required for osteophyte formation in knee osteoarthritis. Matrix Biol. 2013;32(3-4):178-87. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hashimoto S, Creighton-Achermann L, Takahashi K, Amiel D, Cooutts RD, Lotz M. Development and regulation of osteophyte formation during experimental osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;10(3):180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(4):256-60. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Murata K, Kanemura N, Kokubun T, Morishita Y, Fujino T, Takayanagi K. Acute chondrocyte response to controlling joint instability in an osteoarthritis rat model. Sport Sci Health. Epub 2016. September 29. doi: 10.1007/s11332-016-0320-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oprenyeszk F, Chausson M, Maquet V, Dubuc JE, Henrotin Y. Protective effect of a new biomaterial against the development of experimental osteoarthritis lesions in rabbit: a pilot study evaluating the intra-articular injection of alginate-chitosan beads dispersed in a hydrogel. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(8):1099-107. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gerwin N, Bendele AM, Glasson S, Carlson CS. The OARSI histopathology initiative—recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the rat. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(Suppl 3):S24-34. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pritzker KPH, Gay S, Jimenez SA, Ostergaard K, Pelletier JP, Revell PA, et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(1):13-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Little CB, Barai A, Burkhardt D, Smith SM, Fosang AJ, Werb Z, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 13-deficient mice are resistant to osteoarthritic cartilage erosion but not chondrocyte hypertrophy or osteophyte development. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(12):3723-33. doi: 10.1002/art.25002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Udo M, Muneta T, Tsuji K, Ozeki N, Nakagawa Y, Ohara T, et al. Monoiodoacetic acid induces arthritis and synovitis in rats in a dose- and time-dependent manner: proposed model-specific scoring systems. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(7):1284-91. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arunakul M, Tochigi Y, Goetz JE, Diestelmeier BW, Heiner AD, Rudert J, et al. Replication of chronic abnormal cartilage loading by medial meniscus destabilization for modeling osteoarthritis in the rabbit knee in vivo. J Orthop Res 2013;31(10):1555-60. doi: 10.1002/jor.22393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Onur TS, Wu R, Chu S, Chang W, Kim HT, Dang AB. Joint instability and cartilage compression in a mouse model of posttraumatic osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2014;32(2):318-23. doi: 10.1002/jor.22509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Egloff C, Hart DA, Hewitt C, Vavken P, Valderrabano V, Herzog W. Joint instability leads to long-term alterations to knee synovium and osteoarthritis in a rabbit model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(6):1054-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mansour JM, Wentorf FA, Degoede KM. In vivo kinematics of the rabbit knee in unstable models of osteoarthrosis. Ann Biomed Eng. 1998;26(3):353-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.