Abstract

Recent smooth muscle cell (SMC) lineage-tracing studies have revealed that SMCs undergo remarkable changes in phenotype during development of atherosclerosis. Of major interest, we demonstrated that Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) in SMCs is detrimental for overall lesion pathogenesis, in that SMC-specific conditional knockout of the KLF4 gene (Klf4) resulted in smaller, more-stable lesions that exhibited marked reductions in the numbers of SMC-derived macrophage- and mesenchymal stem cell-like cells. However, since the clinical consequences of atherosclerosis typically occur well after our reproductive years, we sought to identify beneficial KLF4-dependent SMC functions that were likely to be evolutionarily conserved. We tested the hypothesis that KLF4-dependent SMC transitions play an important role in the tissue injury-repair process. Using SMC-specific lineage-tracing mice positive and negative for simultaneous SMC-specific conditional knockout of Klf4, we demonstrate that SMCs in the remodeling heart after ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) express KLF4 and transition to a KLF4-dependent macrophage-like state and a KLF4-independent myofibroblast-like state. Moreover, heart failure after IRI was exacerbated in SMC Klf4 knockout mice. Surprisingly, we observed a significant cardiac dilation in SMC Klf4 knockout mice before IRI as well as a reduction in peripheral resistance. KLF4 chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing analysis on mesenteric vascular beds identified potential baseline SMC KLF4 target genes in numerous pathways, including PDGF and FGF. Moreover, microvascular tissue beds in SMC Klf4 knockout mice had gaps in lineage-traced SMC coverage along the resistance arteries and exhibited increased permeability. Together, these results provide novel evidence that Klf4 has a critical maintenance role within microvascular SMCs: it is required for normal SMC function and coverage of resistance arteries.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY We report novel evidence that the Kruppel-like factor 4 gene (Klf4) has a critical maintenance role within microvascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs). SMC-specific Klf4 knockout at baseline resulted in a loss of lineage-traced SMC coverage of resistance arteries, dilation of resistance arteries, increased blood flow, and cardiac dilation.

Keywords: Kruppel-like factor 4, lineage tracing, smooth muscle cells, smooth muscle cell maintenance

INTRODUCTION

Smooth muscle cells (SMCs) are nonterminally differentiated, highly plastic cells that can undergo reversible phenotypic switching from a differentiated, contractile state to a proliferative, migratory state that also exhibits increased extracellular matrix synthesis (1). This plasticity is essential for the development of new blood vessels and repair of those that are damaged. Upon vascular injury or stimulation with a variety of cytokines, including PDGF-BB and IL-1β, SMCs upregulate the stem cell pluripotency factor Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4), resulting in the downregulation of SMC contractile/marker genes, such as myosin heavy chain 11 (Myh11), α-smooth muscle actin (Acta2), and transgelin (Tagln) (43). Indeed, recent SMC lineage-tracing studies by our laboratory and others have shown that attempts to identify SMC-derived cells after injury or during development of atherosclerosis by means of typical SMC marker panels not only failed to identify the majority of SMC-derived cells but also misidentified them as other cell types (8, 13, 37). For example, we showed that >80% of SMC-derived cells are negative for SMC markers such as ACTA2; of these, >50% have activated multiple markers of macrophages, including galectin-3 (LGALS3), CD11b, F4/80, and CD11c, myofibroblasts (ACTA2+MYH11−), and/or mesenchymal stem cells [stem cell antigen-1 (SCA) 1+CD105+] (37). Similar SMC lineage-tracing model systems have been used by other laboratories to show that SMCs also transition to a variety of other cell types, including beige adipocytes in response to cold stress (27) and myofibroblasts after myocardial infarction (MI) induced by permanent ligation of the left anterior descending artery (20).

One of the key proteins that controls SMC phenotypic switching is the zinc finger transcription factor KLF4. KLF4 is not normally expressed within SMCs in large conduit arteries but is rapidly induced upon vascular injury (26). Upon induction, KLF4 contributes to the downregulation of SMC marker genes through several known mechanisms, including KLF4 recruitment by pELK-1 to the G/C repressor regions of SMC marker gene promoters and subsequent recruitment of histone deacetylase (HDAC)2, HDAC4, and HDAC5, resulting in epigenetic silencing of the locus through deacetylation (36, 42). KLF4 induction also reduces expression of the SMC master differentiation control gene myocardin and destabilizes serum response factor binding to SMC marker gene promoters (26). KLF4 can also repress SMC growth, at least in part, through binding to the p21WAF1/Cip1 promoter along with p53 (43). Together, the preceding results indicate that Klf4 is activated upon vascular injury and plays a critical role in regulating phenotypic transitions of arterial SMCs but is not normally expressed in healthy conduit arteries.

Little is known about the factors and mechanisms that control SMC phenotypic transitions in vivo. However, recent studies in our laboratory have shown that KLF4-dependent transitions in SMC phenotype and function play a critical role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. SMC-specific conditional knockout of Klf4 within Western diet-fed apolipoprotein E (ApoE)−/− mice resulted in marked reductions in lesion size and increased multiple indexes of plaque stability, including a doubling of the fibrous cap thickness (37). Notably, loss of Klf4 in SMCs did not change the overall number of SMCs within lesions but significantly reduced the number of SMC-derived macrophage- and mesenchymal stem cell-like cells while increasing the number of ACTA2+ cells that invested in the fibrous cap (37). Comparative in vivo chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-Seq) analyses of advanced atherosclerotic lesions from wild-type and SMC Klf4 knockout mice identified >800 putative KLF4-regulated genes, including >70 genes encoding for markers of macrophage activation, antigen processing, and immune responses (37). These results suggest that Klf4 is critical for the transition of SMCs to a macrophage-like state and that activation of Klf4 within SMCs in atherosclerotic lesions has detrimental consequences in terms of overall lesion pathogenesis. This suggests that Klf4 activation in atherosclerosis is maladaptive and that the activation and function of Klf4 in SMCs evolved for another purpose.

Klf4 activation in SMCs may be beneficial and thus evolutionarily conserved in the setting of the injury-repair process. During the injury-repair process, SMCs need to phenotypically modulate to contribute to the angiogenic process (3). Macrophages and other inflammatory cells, potentially including phenotypically modulated SMCs, are also recruited to the site of injury (40). One example of such an injury-repair process is the healing myocardium after ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI)-induced MI (IRI-MI). After acute IRI-MI, healing of the injured myocardium begins with an influx of inflammatory cells, including large numbers of phagocytic cells positive for macrophage markers that infiltrate the infarct zone and release cytokines as well as matrix metalloproteinases (9, 14). These phagocytic cells also play a critical role in clearing the infarct zone of dead cells and extracellular matrix debris while stimulating myofibroblasts to produce new collagen for formation of fibrotic scar tissue (39a) as well as stimulating angiogenesis and revascularization of the infarct zone (31). SMCs may contribute to the expansion of these groups of phagocytic cells by transitioning to a macrophage-like state through a KLF4-dependent mechanism, similar to that previously seen in atherosclerosis (8, 37). Moreover, additional KLF4-dependent changes in SMC function may influence neovascularization of the infarct zone, including through the secretion of various growth factors and cytokines by SMCs.

The present study used our novel SMC lineage-tracing and conditional Klf4 knockout mice to test the hypothesis that the summation of KLF4-dependent transitions in SMC phenotype and function plays a critical, beneficial role in maintenance of vascular integrity and/or neovascularization during tissue repair. Using an IRI model, we found that SMCs are a relatively minor source of myofibroblasts and macrophages post-IRI-MI, with the macrophage-like transitions being KLF4 dependent. However, contrary to expectations, we discovered that Klf4 plays a critical protective role within resistance vessels at baseline, in that conditional SMC-specific Klf4 knockout resulted in acute reductions in peripheral resistance, a dilated heart, and evidence of increased vascular leakage. These changes appear to be due, at least in part, to reduced coverage of resistance vessels with SMCs and SMC derivatives, as well as dysregulation of key SMC signaling pathways, including PDGF and FGF signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals.

All animal protocols and procedures were performed in accordance with a University of Virginia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol. Myh11-CreERT2 ROSA floxed STOP eYFP, Myh11-CreERT2 ROSA floxed STOP eYFP Klf4WT/WT, and Myh11-CreERT2 ROSA floxed STOP eYFP Klf4fl/fl male littermate control mice were genotyped as previously described (13, 37). Because the Myh11-CreERT2 transgene is located on the Y chromosome, experimental mice were exclusively male. Cre recombinase was activated in male mice with a series of ten 1-mg intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen (catalog no. T-5648, Sigma) from 6 to 8 wk of age, for a total of 10 mg tamoxifen/mouse. Animals were allowed to recover for ≥2 wk to allow residual tamoxifen to leave the system before experiments/tissue isolation.

IRI-MI.

SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 10) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 12) mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg ip) or ketamine-xylazine (80 and 8 mg/kg body wt ip, respectively) and orally intubated. Mice were ventilated with a small animal respirator (150 strokes/min, 150- to 200-µl stroke volume). The heart was exposed by left thoracotomy, and a suture was passed beneath the left anterior descending artery and tightened over a piece of polyethylene-60 tubing for 60 min to occlude the coronary artery. Reperfusion was induced by removal of the tubing. Ketoprofen or buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg body wt sc) was administered as postoperative analgesic.

Tissue harvest and processing.

Mice were euthanized via CO2 asphyxiation. After euthanasia, mice whose tissues were to be used for whole mount preparations or paraffin embedding were perfused through the left ventricle of the heart near the apex with 5 ml PBS followed by 10 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde and another 5 ml PBS. Hearts, mesentery, retinas, and spinotrapezius muscle were dissected, postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min (whole mount preparations) or 2 h (paraffin-embedded tissues), and either embedded in paraffin or processed for whole mount imaging. Paraffin-embedded sections were sectioned serially at 10 µm thickness for further analysis. Heart tissues that were used for frozen sections were processed as described above except that periodate-lysine-paraformaldehyde was used in the place of 4% paraformaldehyde. After postfixation, frozen sections were equilibrated in increasing sucrose gradients (7.5% sucrose overnight, 15% sucrose for 4 h, and 30% sucrose for 2 h) at 4°C. After the final sucrose equilibration, tissues were embedded in OCT, cooled in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until being sectioned. Frozen tissues were sectioned serially at 5 µm thickness for further analysis.

Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence analysis.

Hearts were stained with hematoxylin-eosin 7 days post-IRI. Masson’s trichrome staining was also done 7 days post-IRI. Immunohistochemical staining was done at baseline and 7 days post-IRI using an antibody specific for KLF4 (catalog no. sc20691, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and visualized by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Acros Organic). For immunofluorescent staining of paraffin-embedded, frozen, and whole mount tissues (heart, retina, and spinotrapezius muscle) from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ mice, we used primary antibodies specific for green fluorescent protein (catalog no. ab6673, Abcam, 4 μg/ml), KLF4 (catalog no. AF3158, R&D Systems, 1 µg/ml), LGALS3 (catalog no. CL8942AP, Cedarlane, 2 μg/ml), MYH11 (catalog no. MC-352, Kamiya Biomedical, 1 µg/ml), green fluorescent protein biotinylated (catalog no. ab6658, Abcam, 4 μg/ml), and CD31 (catalog no. DIA-310, dianova, 0.8 μg/ml). Primary conjugated ACTA2-FITC antibody (catalog no. F3777, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:500 dilution) was also used. Secondary antibodies used for immunofluorescence included donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 555 (catalog no. A21432, Life Technologies, 1:250 dilution), donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 647 (catalog no. A21447, Life Technologies, 1:250 dilution)-streptavidin, Alexa Fluor 555 (catalog no. S32355, Life Technologies, 1:250 dilution), and donkey anti-rat DyLight 650 (catalog no. ab102263, Abcam, 1:200 dilution). DAPI (catalog no. D3571, ThermoFisher Scientific, 0.05 mg/ml) was used to label DNA.

Image capture and analysis.

Hematoxylin-eosin, Masson’s trichrome, and KLF4 DAB staining was captured using a Zeiss Axioskop 2 microscope fitted with an AxioCamMR3 camera. Images were acquired using AxioVision v4.6.3.0 software (Carl Zeiss Imaging Solution). Digitized images of Masson’s trichrome staining were analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 7.0 software (Media Cybernetics). Areas of interest were drawn within the software to demarcate the infarct zone and the left ventricle, and the areas of these regions were calculated.

Immunofluorescence images were captured using a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope. Zen 2009 Lite software (Zeiss) was used to acquire a z-stack image at 1-µm intervals at 2,048 × 2,048 or 1,024 × 1,024 resolution. Analysis of z-stack images was performed in Zen 2009 Lite software. Cell markers were quantified manually in the Zen 2009 software on z-stack images to assess colocalization of markers within a single cell (DAPI+ nucleus). Gaps in eYFP+ cell coverage were quantified using the line segment distance tool in the Zen 2009 software. Images are maximum-intensity projections of the confocal z stacks. CD31 immunofluorescence pixilation was done in Image-Pro Plus 7.0 software (Media Cybernetics). Positive staining color in the left ventricle was chosen at the pixel level and defined using a color cube-based method. The area of the left ventricle was calculated as described for Masson’s trichrome analysis.

Echocardiography.

Echocardiography was performed on a FUJIFILM VisualSonics Vevo 2100 system. Briefly, mice were anesthetized via inhaled isoflurane induction at 2.5% + 500 ml/min O2 flow and maintained at 1% + 500 ml/min O2 flow. Body temperature, heart rate, and respiration rate were monitored throughout the procedure. Warmed Aquasonic ultrasound gel (catalog no. 01-08, Parker Laboratories) was applied over the thorax, and a 30-MHz probe was positioned over the chest in a parasternal position for image acquisition. Long- and short-axis B- and M-mode images were captured at heart rates between 400 and 600 beats/min and respiration rates between 100 and 120 breaths/min. Heart parameters and function were analyzed using Vevo 2100 linear-array imaging system software and Simpson’s method.

Blood pressure measurements.

SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 5) mice were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane + O2 and placed on a heated surgery table. The right carotid artery was exposed and cannulated with a Millar catheter. Blood pressure was measured, and animals were euthanized.

Blood flow measurements.

Perfluorobutane microbubbles stabilized with the lipid monolayer shell were prepared as previously described (23). Microbubbles were subjected to flotation to remove large particles to ensure lack of microbubble retention in the capillaries. Microbubbles (~9 × 108 particles/ml, mean size: ~2 μm, as determined by Coulter counter) were injected as an intravenous bolus into isoflurane-anesthetized SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 5) animals on a warming pad. Contrast ultrasound imaging of hindlimb vasculature was performed with a clinical-grade Sequoia c512 instrument equipped with a 15L8 probe in contrast pulse-sequencing mode at 7 MHz. Lateral spatial resolution of contrast ultrasound imaging at 7 MHz is ~0.2 mm; beam elevation at the focal zone is <1 mm. Coupling between the tissue and the probe was achieved with ultrasound gel. Microbubbles in the target vasculature were destroyed by a high-intensity pulse (mechanical index: 1.9), and inflow of microbubbles into the muscle was observed as replenishment of contrast, in real time (10 Hz), at a mechanical index of 0.2, which is not destructive to the microbubbles in the field of view. Contrast replenishment video was processed using Siemens Syngo software to compute the time constant of the replenishment curve according to a single-exponential equation: y = A(1 − e−βt), where A is the plateau video intensity or microvascular cross-sectional area and β is the rate of rise of the video intensity or microbubble velocity. Relative volumetric flow (F) was calculated using the following equation: F = Aβ (41). Flow was measured within a region of interest in the microvasculature of the quadriceps femoris (adjacent to the femoral artery).

Pressure myography.

Pressure myography was done on SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 3) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 3) animals, as previously described (4). Briefly, mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, and first-order mesenteric arteries were isolated and placed in Krebs-HEPES buffer containing (in mM) 118.4 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 4 NaHCO3, 1.2 KH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, and 6 glucose. Isolated vessels were transferred to a pressure arteriograph (Danish MyoTechnology), cannulated at each end with a glass micropipette, and secured with 10-0 nylon monofilament suture. Arteries were perfused with Krebs-HEPES buffer supplemented with 1% BSA and superfused with Krebs-HEPES buffer. Arteries were pressurized to 80 mmHg and heated to 37°C for 30 min for equilibration.

After equilibration, vessels were stimulated with cumulative concentrations of phenylephrine (PE; 2 vessels/animal, 10−9−10−4 M, Sigma), acetylcholine (ACh; 4 wild-type vessels and 3 knockout vessels, 10−9−10−3 M), or sodium nitroprusside (SNP; 7 wild-type vessels and 8 knockout vessels, 10−10−10−3 M), and luminal diameter (in µm) was assessed using the DMT data acquisition suite. Values are means ± SE or percent maximal luminal diameter. Maximal luminal diameter was determined at the end of the PE dose response by incubation of arteries in Ca2+-free Krebs-HEPES buffer containing EGTA (2 mmol/l) and SNP (10 μmol/l).

Passive diameter (2 vessels/animal) was measured by increasing intraluminal pressure from 0 to 140 mmHg in 20-mmHg increments in Ca2+-free Krebs-HEPES buffer supplemented with EGTA and SNP, as described above. Luminal diameter was measured as described above and expressed as means ± SE or the percent increase from 0 mmHg.

KLF4 ChIP-Seq analysis.

Mesenteric arcades were isolated from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ mice (n = 7) and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen tissues were ground in a mortar and pestle, resuspended in PBS with sodium butyrate (catalog no. B5887, Sigma-Aldrich, 20 mM), and spun at 500 g in a centrifuge to remove lipids. The remaining cells were pooled by mouse genotype and processed for ChIP-Seq as previously described (37). Briefly, cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Cross-linked chromatin was then sheared by sonication into 200- to 600-bp fragments, which were immunoprecipitated with anti-KLF4 (catalog no. sc20691, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 2 µg) antibody complexed with magnetic bead-coupled protein G (catalog no. 10004D, ThermoFisher Scientific, 10 µl/sample). Genomic DNA was eluted and purified off the bead complexes, and a library was constructed using the TruSeq DNA sample guide protocol (Illumina) following the manufacturer's instructions. Sequencing was performed at the University of Virginia Genomics Core using an Illumina MiSeq sequencing system.

Sequencing reads from an Illumina MiSeq sequencing system were aligned to the mouse genome (mm9 assembly) using the Bowtie alignment tool (24). These aligned reads were processed and converted to bam.bai format (http://genome.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/help/bam.html) and then loaded in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (http://www.broadinstitute.org/igv/) for visualization. The processing steps involved removal of duplicate reads and format conversions using the SAMTools suite (25). The reads were also converted to BED format (http://genome.ucsc.edu/FAQ/FAQformat#format1) for further data analyses, such as peak calling. KLF4 peaks were identified using MACS14 (44) with SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ as input and P ≤ 1 × 10−6 for significant peak calling. Once peaks were obtained, BEDTools (34) was used to identify the genes closest to each peak. Functional annotation was performed using Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (18) and Protein Analysis Through Evolutionary Relationships (PANTHER; http://pantherdb.org/) (29). The Gene Expression Omnibus accession number is GSE107641.

Intravital confocal microscopy.

Intravital confocal microscopy of the cornea was performed as previously described (22). Briefly, SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 7) mice were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine-atropine [60, 4, and 0.2 mg/kg body wt ip, respectively, Zoetis (Kalamazoo, MI), West-Ward (Eatontown, NJ), and Lloyd Laboratories (Shenandoah, IA), respectively]. The eye was numbed by administration of topical anesthetic (a drop of sterile 0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution) before imaging. Mice were imaged on a confocal microscope (model TE200-E2, Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, ×20 objective optimized for 2 channels, laser excitation wavelengths at 488 and 543 nm). Ophthalmic lubricant (GenTeal, Alcon, Fort Worth, TX) was applied to the eye to prevent drying during imaging. Eyelashes and whiskers were gently pushed back with GenTeal gel, mice were placed on a microscope stage with a warming pad, and the snout was gently restrained with a nose cone.

Permeability measurements and quantification.

After the mice had been anesthetized, 70-kDa dextran-rhodamine B (catalog no. D1841, ThermoFisher, 5 mg/ml) was administered via a retroorbital injection immediately before imaging, such that movie recording started <5 min postinjection. Digital images of the vascular networks were acquired using a NikonTE200-E2 confocal microscope, as described above. One field of view per cornea was imaged with full-thickness z-stacks (25–30 slices at 3-μm intervals) on repetition for 60 min. To capture the entire corneal vascular network in the field of view, we used the maximum-intensity projection to create volume renders of z-stacks. Using ImageJ, we measured the mean pixel intensity in three equal-size regions of interest (ROIs), which were evenly distributed across three different areas in the field of view (above the limbus, in vascular loops within the limbus, and below the arterial-venous pair defining the start of the limbus) for a total of nine ROIs analyzed per frame. These values were plotted against time. Finally, we quantified the area under the curve to capture the total leakage of dextran from the vasculature over time. Researchers were blinded to the genotype of the animals until the end of analysis.

Bone marrow transfer.

Bone marrow transfers were performed as previously described (19). Briefly, eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 3) recipient mice were lethally irradiated with a dose of 1,200 rad (2 exposures to 600 rad, 3 h apart). At 30 min after irradiation, unfractionated bone marrow cells taken from femurs of whole body DsRED+ mice were administered to recipient mice via retroorbital injections at 1 × 106 cells/mouse. Bone marrow was allowed to reconstitute for 6 wk. After 6 wk, mice received the normal series of 10 intraperitoneal tamoxifen injections (1 mg tamoxifen, catalog no. T-5648, Sigma). After 2 wk of rest, mice received a retroorbital injection of isolectin-Alexa Fluor 647 (catalog no. I32450, ThermoFisher) 30 min before euthanasia. Tissues were then isolated and processed for whole mount imaging.

Statistical analysis.

Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software. The Kolmogorov-Smirnoff test was used to determine if data were normal. Two-way ANOVA was performed to assess genotype contributions to various echocardiography parameters across multiple time points and also to compare groups in pressure myography experiments. For individual comparisons between data, unpaired two-tailed t-tests were performed. Welch’s correction was applied when variance was not equal between groups. Mann-Whitney U-tests, instead of t-tests, were performed if the data were nonnormally distributed.

RESULTS

KLF4 is upregulated in SMCs within the infarct zone after IRI-MI.

Using our previously described tamoxifen-inducible SMC lineage-tracing system (Myh11-CreERT2 ROSA floxed STOP eYFP, SMC YFP+/+) (13), we began by determining if SMCs express KLF4 post-IRI-MI. In agreement with the literature, we found no evidence of eYFP+ lineage-traced SMCs expressing KLF4 at baseline (Fig. 1A, yellow arrows). However, after 1 h of left anterior descending artery occlusion followed by reperfusion, there was a marked increase in KLF4 expression within the heart, especially within the infarct zone (Fig. 1B). A subset of these KLF4-expressing cells were eYFP+, indicating that they were of SMC origin (Fig. 1C, white arrows). Based on these observations, we proceeded to test how SMC-specific conditional knockout of Klf4 impacted cardiac function before and after IRI-MI induced by a 60-min ligation of the left anterior descending artery. Myh11-CreERT2 ROSA floxed STOP eYFP Klf4fl/wt male and ROSA floxed STOP eYFP Klf4fl/wt female mice were bred, yielding a 1:2:1 ratio of Myh11-CreERT2 ROSA floxed STOP eYFP Klf4wt/wt and Myh11-CreERT2 ROSA floxed STOP eYFP Klf4fl/fl male littermate control mice for experimental use. After a series of 10 tamoxifen injections at 6–8 wk of age, we observed high-efficiency (>95%), simultaneous activation of the eYFP reporter gene and knockout of Klf4 exclusively in SMCs in Klf4fl/fl mice, yielding Myh11-CreERT2 ROSA floxed STOP eYFP Klf4Δ/Δ mice (Fig. 1, C and D) [henceforth referred to as SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT littermate control mice for simplicity].

Fig. 1.

Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) is upregulated in smooth muscle cells (SMCs) in the infarct zone after ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI)-induced myocardial infarction (MI). A: representative immunofluorescence images of hearts from SMC eYFP+/+ mice (n = 8) at baseline. Yellow arrows highlight eYFP+KLF4− cells; white arrows highlight eYFP−Klf4+ cells. ACTA2, α-smooth muscle actin. Scale bars = 20 µm. B: representative 3,3′-diaminobenzidine staining for KLF4 within hearts at baseline and 7 days post-IRI-MI. C: representative immunofluorescence images from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 9) animals 7 days post-IRI-MI. Note marked decrease in eYFP+KLF4+ cells in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals. White arrows highlight eYFP+KLF4+ cells; yellow arrows highlight eYFP+KLF4− cells. Scale bars = 20 µm. D: quantification of eYFP+KLF4+ cells in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 9) animals 7 days post-IRI-MI. **P < 0.01 (by unpaired, 2-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction).

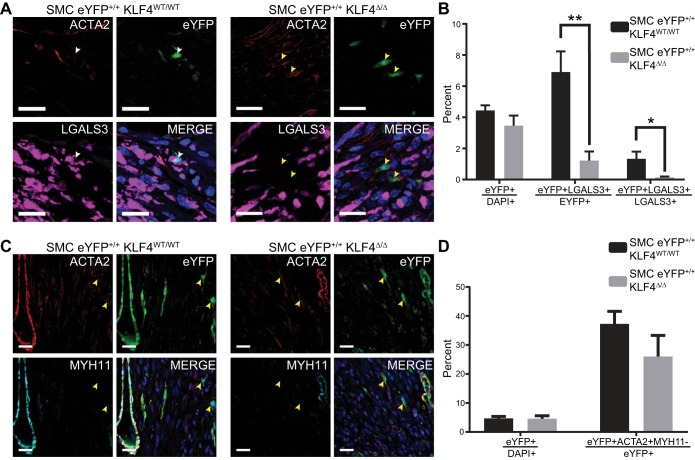

A subset of SMCs transitioned to macrophage- and myofibroblast-like cells after IRI-MI.

To determine if SMCs contribute to macrophage and myofibroblast cell populations post-IRI-MI, we used our SMC YFP+/+ mice to ascertain SMC phenotypic switching. At 7 days post-IRI-MI, a subset of SMCs transitioned to a LGALS3+ macrophage-like state (Fig. 2A). However, these macrophage-like SMCs comprised <2% of the overall LGALS3+ macrophage population (Fig. 2B). Using our SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ mice, we found that Klf4 knockout significantly reduced the number of SMCs that transitioned to a LGALS3+ macrophage-like state (Fig. 2, A and B). This reduction in SMC-derived LGALS3+ macrophage-like cells after SMC-specific Klf4 knockout is consistent with our previous work in the setting of atherosclerosis (37). We also examined whether the previously reported SMC-to-myofibroblast transitions (20) were KLF4 dependent. Knockout of Klf4 had no effect on SMC transitions to a myofibroblast-like state (eYFP+Acta2+Myh11−), again consistent with our published work on late-stage atherosclerosis (Fig. 2, C and D). Together, these results demonstrate a role for Klf4 in the phenotypic switching of SMCs to a macrophage-like, but not a myofibroblast-like, state. However, the overall contributions of SMCs to these populations was <1% for myofibroblasts (20) and <2% for macrophages. Nevertheless, given that Klf4 regulates multiple SMC responses, including growth and suppression of SMC marker genes (36, 42, 43), as well as our previous evidence of >800 KLF4 target genes in SMCs, we proceeded to determine if knockout of Klf4 in SMCs had any functional effects after IRI-MI.

Fig. 2.

Smooth muscle cell (SMC)-specific Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) knockout impairs SMC phenotypic switching to macrophage-, but not myofibroblast-like, cells. A: representative immunofluorescence images of SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 9) animals 7 days after ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced myocardial infarction (IRI-MI). Note marked decrease in eYFP+LGALS3+ cells in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals. White arrows highlight eYFP+LGALS3+ cells; yellow arrows highlight eYFP+LGALS3− cells. ACTA2, α-smooth muscle actin; LGALS3, galectin 3. Scale bars = 20 µm. B: percent eYFP+ cells within the infarct zone, percent eYFP+ cells that are LGALS3+ within the infarct zone, and percent LGALS3+ cells that are eYFP+. Knockout of Klf4 resulted in a decrease of eYFP+LGALS3+ cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (by unpaired, 2-tailed t-test for percent eYFP+ cells and by unpaired, 2-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction for percent eYFP+ cells that are LGALS3+ and percent LGALS3+ cells that are eYFP+). C: representative immunofluorescence images of SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 7) animals 7 days post-IRI-MI. Note no difference in eYFP+ACTA2+MYH11− cells in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ compared with SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT animals. Yellow arrows highlight eYFP+ACTA2+MYH11− cells. MYH11, myosin heavy chain 11. Scale bars = 20 µm. D: quantification of percent eYFP+ cells within the infarct zone and percent eYFP+ cells that are eYFP+ACTA2+MYH11− myofibroblast-like cells within the infarct zone. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (by unpaired, 2-tailed t-test).

SMC-specific Klf4 knockout induced cardiac dilation at baseline and exacerbated development of ischemia-dilated cardiomyopathy.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining of hearts 7 days post-IRI-MI revealed that SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals had dilated hearts compared with wild-type littermate control mice (Fig. 3A) and also exhibited an increase in heart weight-to-body weight ratio at 21 days post-IRI-MI (Fig. 3B). Infarct size relative to left ventricle size was not increased in knockout compared with wild-type animals 7 days post-IRI-MI (Fig. 3C). Cardiac dilation in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ mice was further confirmed by echocardiographic analyses of the left ventricle. After IRI-MI, SMC-specific Klf4 knockout animals had significantly increased end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes (Fig. 3, D and E). Functional parameters, including ejection fraction and cardiac output, were not different between knockout and wild-type animals but decreased over time, as expected, after IRI-MI (Fig. 3, F–I).

Fig. 3.

Smooth muscle cell (SMC)-specific Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) knockout leads to increased cardiac dilation after myocardial infarction (MI). A: representative images of hematoxylin-eosin staining of SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 9) animals 7 days after ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI)-induced MI (IRI-MI). Note cardiac dilation in knockout animals. Scale bars = 1 mm. B: heart weight-to-body weight ratios for SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 3) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 4) animals 21 days post-IRI-MI. *P < 0.05 (by unpaired, 2-tailed t-test). C: quantification of infarct area as a ratio of left ventricle area for SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 9) animals 7 days post-IRI-MI. D and E: echocardiography time course of SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT animals at 0 (n = 12), 7 (n = 6), 14 (n = 3), and 21 (n = 2) days post-MI and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals at 0 (n = 14), 7 (n = 9), 14 (n = 5), and 21 (n = 5) days post-MI. End-systolic and end-diastolic volumes and cardiac dilation were increased in knockout animals. **P < 0.01 (by 2-way ANOVA). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 (by unpaired, 2-tailed t-test). There was also a significant increase in end-systolic and end-diastolic volume at baseline. F–I: echocardiography time courses examining stroke volume, ejection fraction, fractional shortening, and cardiac output. Note decreases, as expected, post-IRI-MI but no difference between knockout and wild-type animals.

Closer examination of the echocardiography data showed significant increases in end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes at baseline, i.e., before IRI-MI (Fig. 4, A and B), which is only 2 wk after the last tamoxifen injection and 4 wk since the first of our series of 10 tamoxifen injections required to induce >95% Cre recombinase-dependent eYFP activation and genetic knockout of Klf4 in SMCs (37). The increase in end-diastolic volume was larger than the increase in end-systolic volume, resulting in an increase in stroke volume (Fig. 4C). These data suggest that SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals had a preexisting cardiac dilation as a consequence of Klf4 knockout in SMCs. This preexisting cardiac dilation would likely negatively impact recovery of knockout animals after IRI-MI.

Fig. 4.

Smooth muscle cell (SMC)-specific knockout of Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) leads to left ventricular dilation, decreased blood pressure, and increased blood flow at baseline. A–C: echocardiography analysis of end-systolic volume, end-diastolic volume, and stroke volume at baseline in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 12) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 14) animals. D: CD31+ pixel density within the left ventricle of SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 6) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 6) animals at baseline. E: blood pressure measured using a carotid blood pressure probe shows an ~5-mmHg drop in blood pressure in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 5) animals at baseline. F: relative volumetric blood flow rate measured by contrast ultrasound in an area of interest near the femoral artery in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 5) animals. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (by unpaired, 2-tailed t-test).

To investigate whether an altered myocardial capillary density, previously shown to be associated with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy in humans (39), contributes to the cardiac dilation we found in our baseline SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals, we examined CD31+ vascular density within the left ventricle (Fig. 4D). CD31+ vascular density was not altered in baseline SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ compared with SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT animals. Another potential cause of left ventricular dilation is a reduction in peripheral resistance. Thus, we next examined blood pressure (P) and blood flow rate (Q̇), the two main determinants of peripheral resistance (R), in our mice (Q̇ = P/R). A ~5-mmHg drop in mean arterial blood pressure in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals at baseline was measured using a carotid blood pressure probe (Fig. 4E). To calculate blood flow within the resistance arteries, we used contrast ultrasound combined with injectable microbubbles. We began by destroying the bubbles within the vasculature of the leg with an ultrasonic pulse and measured the subsequent bubble refill rate in a ROI within the microvasculature of the quadriceps femoris. In SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals, relative volumetric flow rate within the ROI was increased (Fig. 4F). Together, these data support the conclusion that Klf4 has a previously unknown, protective role in SMC homeostasis and that its loss results in a reduction in peripheral resistance. The main vessels responsible for peripheral resistance and blood pressure control are the resistance arteries, so we next investigated the contractile properties of the resistance arteries in our SMC Klf4 knockout and wild-type control mice.

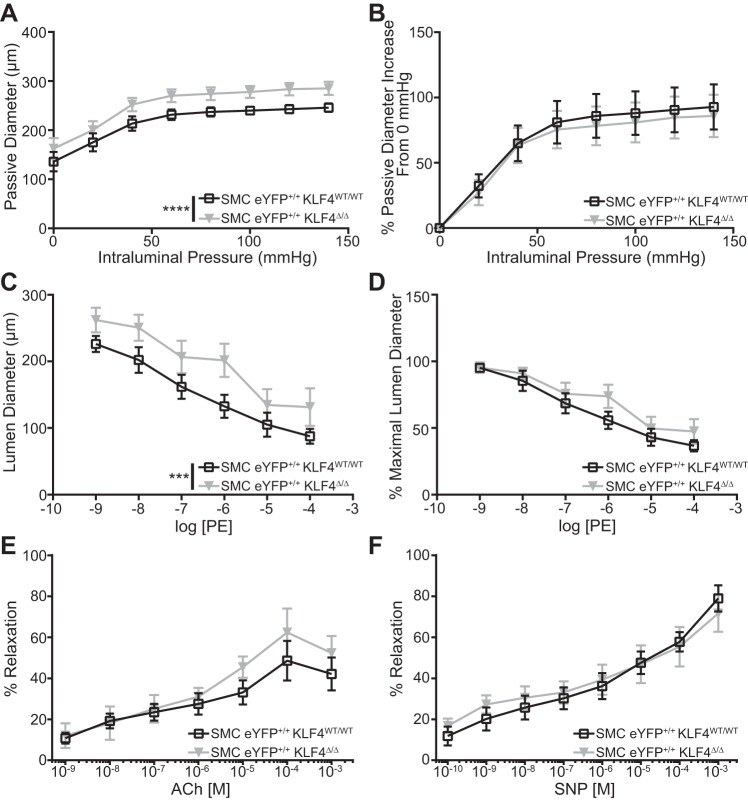

SMC Klf4 knockout resulted in increased resistance vessel passive diameter indicative of outward remodeling.

To investigate the effect of knockout of Klf4 in SMCs on resistance artery function, we performed pressure myography on first-order mesenteric arteries. Under Ca2+-free conditions, the diameter of first-order arteries from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ mice was increased at all pressures compared with these same resistance vessels from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT littermate control mice (Fig. 5A). However, the vessel response to increasing pressure was the same in knockout and wild-type mice, indicating that SMC Klf4 knockout did not alter the mechanical properties of the vessel (Fig. 5B). Similarly, diameter was increased in resistance vessels from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ mice compared with SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT littermate control mice during PE-induced contraction in Ca2+-containing medium (Fig. 5C). However, there was no change in the ability of knockout vessels to contract in response to PE stimulation compared with wild-type vessels (Fig. 5D). A possible explanation for changes in vessel diameter in our SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ mice is an alteration in the vessel’s response to the vasodilator nitric oxide (NO). Thus, we examined whether there was a change in endothelial-dependent (ACh-treated; Fig. 5E) or endothelium-independent (SNP-treated; Fig. 5F) activation of the NO axis in isolated first-order mesenteric vessels from our SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals. We observed no difference between the knockout and wild-type vessels (Fig. 5, E and F). Together, these results indicate that the reduced blood pressure and cardiac dilation in SMC-specific Klf4 knockout mice is due, at least in part, to outward remodeling and/or dilation of resistance arteries. This remodeling and/or dilation is not accompanied by a change in PE dose responsiveness or the vessel’s response to NO. That is, results indicate that Klf4 appears to be required for the maintenance of normal resistance vessel structure (i.e., size).

Fig. 5.

First-order mesenteric resistance arteries from smooth muscle cell (SMC)-specific Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) knockout animals are dilated compared with those from their wild-type counterparts. A: pressure myography assessment of passive properties of 1st-order mesenteric vessels from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 3) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 3) animals (2 vessels per animal) at baseline. SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ vessels were significantly dilated compared with SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT vessels under all pressures. B: passive diameters normalized to respective diameters at 0 mmHg. C: pressure myography assessment of phenylephrine (PE) response of 1st-order mesenteric vessels from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 3) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 3) animals at baseline (2 vessels per animal). Vessels from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals were significantly dilated compared with those from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT animals at all PE concentrations. D: PE-stimulated luminal diameter normalized to respective maximal luminal diameter. E: pressure myography assessment of endothelial-dependent acetylcholine (ACh) response of 1st-order mesenteric vessels from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 3, total vessels = 4) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 3, total vessels = 3) animals at baseline. F: pressure myography assessment of endothelial-independent sodium nitroprusside (SNP) response of 1st-order mesenteric vessels from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 3, total vessels = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 3, total vessels = 8) animals at baseline. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 (by 2-way ANOVA).

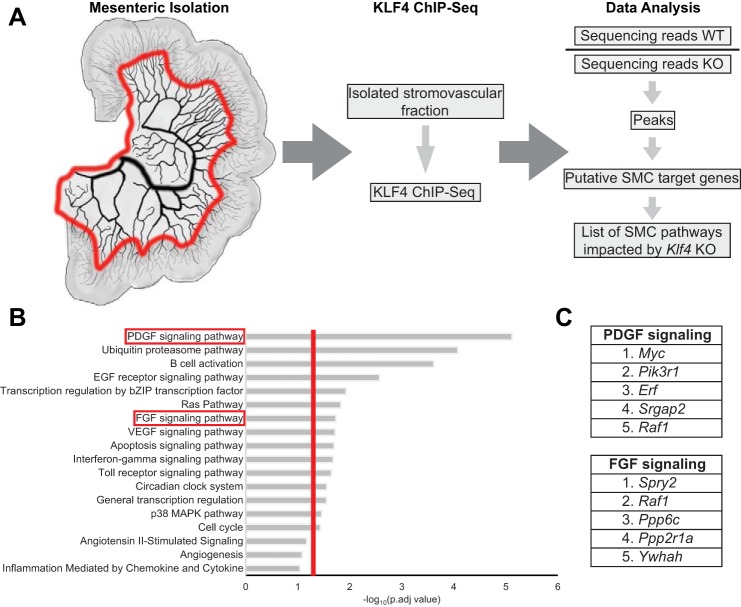

In vivo KLF4 ChIP-Seq identified PDGF signaling as a key pathway regulated by KLF4 within the mesenteric vascular bed.

To begin to understand the genes that might be regulated by KLF4 to cause these unexpected baseline changes in resistance vessel structure and function associated with acute SMC-specific Klf4 knockout, we used comparative in vivo KLF4 ChIP-Seq analysis of the mesenteric resistance vessel arcade from our SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT control mice to identify SMC KLF4-regulated genes and gene pathways. ChIP-Seq analysis of complex tissue samples that consist of numerous different cell types and phenotypes is usually highly problematic, in that it is nearly impossible to ascertain the changes contributed by one cell type versus another. Moreover, many differences may be lost due to inadequate sensitivity in detecting even large changes in relatively low-abundance, but functionally important, cell types, including SMCs. In contrast, ChIP-Seq analysis in our experimental SMC Klf4 knockout model allows us to ascertain overall changes (i.e., primary and secondary) resulting from initial conditional loss of a single gene (i.e., Klf4) exclusively in SMCs. As such, to identify putative KLF4 target genes within SMCs in resistance vessels that could mediate our structural and functional changes, we used KLF4 ChIP-Seq to analyze chromatin extracted from mesenteric resistance vessel arcades from our SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals 2 wk after the last tamoxifen injection (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-Seq) identified the PDGF signaling pathway as differentially regulated between smooth muscle cell (SMC) Klf4 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) animals. A: cartoon representation of the area taken for the KLF4 ChIP-Seq and analysis work flow. Red line on mesentery indicates where the tissue was cut. B: Enriched Protein Analysis Through Evolutionary Relationships (PANTHER) pathways in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) compared with SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 7) animals. Vertical red line indicates P = 0.05 [calculated using Database for Annotation Bioinformatics Microarray Analysis (DAVID) software]. C: top-5 enriched genes in PDGF and FGF signaling pathways.

Briefly, SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT sequencing reads were normalized to SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ reads to identify those that were enriched in wild-type animals. The remaining reads were tabulated as peaks and associated with genes, resulting in a list of putative SMC KLF4 target genes that were subjected to pathway enrichment analysis (Fig. 6A). Of major interest, these analyses identified the PDGF signaling pathway as the most significantly enriched pathway (P < 0.0001; Fig. 6B). PDGF signaling is known to be critical for SMC investment of nascent blood vessels during vascular development and angiogenesis (2, 12, 38). However, surprisingly, there is no known role of PDGF signaling in homeostasis of the normal vasculature (2). Other enriched pathways include FGF signaling and angiogenesis as well as several inflammatory pathways, such as interferon-γ signaling and Toll-like receptor signaling (Fig. 6B). The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, which is involved not only in protein degradation but also in trafficking (17), was also enriched in our Klf4 ChIP-Seq (Fig. 6B). Intriguingly, the enriched genes within these pathways do not simply include the receptors but also a host of kinases, phosphatases, and transcription factors (Fig. 6C).

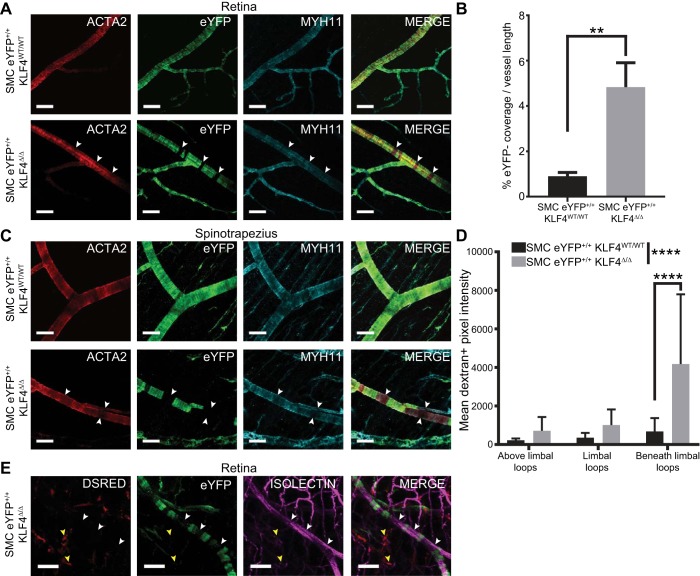

Resistance vessels from SMC Klf4 knockout mice exhibit gaps in SMC coverage.

Given our results showing that KLF4 regulates several pathways previously shown to be critical in regulating SMC growth, migration, and investment of blood vessels, we next sought to determine if SMC loss of KLF4 expression and subsequent reductions in blood pressure and peripheral resistance might be associated with morphological changes in resistance vessels. We focused our evaluations of resistance vessel morphology on the retina 2 wk after the last tamoxifen injection, given the ease of obtaining very high-resolution, low-background images of the entire vascular network by use of whole mount preparations. Of major interest, an approximately fourfold increase in prominent gaps in eYFP+ perivascular cell coverage (eYFP− vascular area) was found in resistance arteries of SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ mice compared with SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT mice, which had small eYFP+ coverage gaps (Fig. 7A, white arrows, and Fig. 7B).These gaps in eYFP+ coverage still had ACTA2+MYH11+ perivascular cells investing the arteriole (Fig. 7A, white arrows) and were not bulging outward, suggesting that these replacement perivascular cells are functional. These eYFP− gaps were also present in other vascular beds, including the spinotrapezius muscle (Fig. 7C). Notably, the eYFP− cells within the gaps are unlikely to represent SMCs that failed to undergo Cre recombination, given that we observed no differences in recombination frequencies within large vessels of SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ compared with SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT mice in our previous studies in this model (13, 37) and that the Cre recombination frequency of the eYFP reporter gene locus is extremely unlikely to differ between SMC Klf4 knockout and wild-type mice. As such, the gaps are likely to represent loss of SMC coverage of resistance vessels and subsequent replacement by a non-SMC source that did not express Myh11 at the time of tamoxifen injections.

Fig. 7.

Smooth muscle cell (SMC)-specific knockout of Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) results in noncontinuous lineage-traced SMC coverage along vessels in the microvasculature. A: representative whole-mount immunofluorescence images of retinas from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 8) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 8) animals. White arrows highlight gaps in eYFP+ cell coverage that have been filled with cells expressing α-smooth muscle actin (ACTA2) and myosin heavy chain 11 (MYH11) but not eYFP. Scale bars = 50 µm. B: percent eYFP− length compared with whole vessel length in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 5) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 6) retinas. **P < 0.01 (by Mann-Whitney U-test). C: representative whole-mount immunofluorescence images of spinotrapezius muscle from SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 8) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 8) animals. White arrows highlight gaps in eYFP+ cell coverage that have been filled with cells expressing ACTA2 and MYH11 but not eYFP. Scale bars = 50 µm. D: vascular leakage within the limbal vascular bed of the cornea based on intravital microscopic evaluation of interstitial levels of 70-kDa dextran at 0–1 h postinjection. Results show area under the curve for dextran+ pixels in the interstitial space near the vasculature in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT (n = 7) and SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ (n = 7) animals. ****P < 0.0001 (by 2-way ANOVA for comparisons across the entire vascular network and Sidak’s multiple comparisons between individual locations). E: lethally irradiated SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals received a bone marrow transfer from whole animal constitutive DsRED+ mice. No DsRED+ cells (yellow arrows) were found in the eYFP+ SMC gaps in the spinotrapezius muscle (white arrows). Scale bars = 50 µm.

To determine if the areas of incomplete eYFP+ cell coverage were leaky, mice were perfused with a 70-kDa dextran-rhodamine dye, and real-time in vivo confocal microscopy was used to examine the corneas for presence of the dye outside the vasculature. Significant leakage of dye into the interstitium was seen in the areas beneath the limbal vessels in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ mice (Fig. 7D). Leakage across the entire network increased significantly in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ compared with SMC eYFP+/+Klf4WT/WT mice. There was no evidence of red blood cells or fibrin deposits adjacent to the gaps, suggesting that there was no frank loss of endothelial integrity in these regions, although the possibility of a transient loss of endothelial integrity that did not persist cannot be ruled out.

Next, we investigated whether bone marrow-derived cells were the source of the replacement cells within the eYFP+ gaps. Six-week-old SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ mice underwent lethal irradiation and a bone marrow transfer from constitutive globally labeled DsRED+ mice. Mice were allowed 6 wk to recover, treated with a series of 10 tamoxifen injections over 2 wk, and harvested 2 wk later to simulate our original SMC Klf4 knockout experiments. DsRED+ cells were observed in the interstitium of retina whole mounts, an indication of successful bone marrow reconstitution (Fig. 7E, yellow arrows). The microvasculature of these mice showed that the cells occupying the gaps in eYFP+ coverage (eYFP− vascular area) in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ animals were not DsRED+ and, thus, were not derived from a bone marrow cell source (Fig. 7E, white arrows).

Together, these results indicate the following. First, preexisting SMCs normally maintain continuous SMC coverage of resistance vessels through a process that is KLF4 dependent. Second, upon SMC-specific conditional knockout of Klf4, preexisting differentiated SMC coverage of resistance vessels is lost. These lost SMCs are rapidly replaced from a non-bone marrow-derived source of undetermined origin. Third, the replacement cells express classical SMC marker genes such as Acta2 and Myh11 but fail to maintain normal vascular integrity. Finally, the overall consequence of conditional genetic loss of Klf4 in SMCs is impaired maintenance of peripheral resistance likely due, in part, to outward remodeling and functional dilation of resistance vessels.

DISCUSSION

Klf4 has been shown to be undetectable within large conduit arteries at baseline but is rapidly upregulated upon vascular injury (26, 43). We show compelling evidence that Klf4 has a previously unknown, beneficial, functional role in microvascular SMCs within resistance arteries at baseline. Knockout of Klf4 specifically in SMCs resulted in far-reaching cardiovascular effects, including loss of SMC perivascular coverage (Fig. 7), leaky vasculature (Fig. 7C), dilation of resistance arteries (Fig. 5), overall reduction in peripheral resistance (Fig. 4, E and F), and heart dilation (Fig. 4, A and B). We postulate that loss of KLF4 expression within SMCs in resistance vessels resulted in transient loss of SMC perivascular coverage but ultimate replacement with ACTA2+MYH11+ cells derived from a non-SMC and non-myeloid source yet to be determined. This replacement results in an increased permeability of the vasculature and was associated with significant dilation of resistance vessels. Although this dilation was modest, it was sufficient to result in reduced peripheral resistance, as peripheral resistance changes as a function of the fourth power of changes in vessel radius. The extent to which the resistance vessel dilation is a function of outward vessel remodeling is unclear. It is also unclear whether these functional changes may be related to the loss of SMC coverage of resistance vessels in SMC Klf4 knockout mice and/or replacement of the lost SMCs by cells from a non-SMC source. However, the net result was an increased diameter at any given intraluminal pressure, which likely is the primary cause of reductions in peripheral resistance. This increased vessel diameter was not due to changes in the response to NO but may have been the result of a change in the availability of NO, which has been shown to play a key role in flow-induced arteriolar remodeling (15, 35).The reductions in peripheral resistance (and accompanying hypotension) may contribute to the heart dilation, as very low diastolic blood pressures have been associated with increased cardiovascular risk (10, 11, 21), even in nonhypertensive individuals (28, 33), although the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood.

We also demonstrated KLF4-dependent phenotypic switching of SMCs to a macrophage-like state after IRI-MI. The eYFP+ population of lineage-traced SMCs made up <2% of macrophages within the myocardium, suggesting a limited role for this process within the healing myocardium. However, this limited number of macrophage-like SMCs may still influence the infarct zone through paracrine signaling. Our KLF4 ChIP-Seq on mesenteric arcades (Fig. 6), as well as our previous KLF4 ChIP-Seq on atherosclerotic lesions (37), identified >70 KLF4-regulated proinflammatory genes, including numerous cytokines known to be involved in regulating recruitment and/or the function of inflammatory cells such as macrophages and T cells. These data, coupled with the enrichment in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (Fig. 6B), suggest that macrophage-like SMCs may indeed have a paracrine role following IRI-MI, by influencing the abundant populations of inflammatory cells that infiltrate the infarct zone post-IRI-MI. The data also more broadly suggest that SMC paracrine signaling may be important in a variety of other pathological conditions, such as diabetes, metabolic disease, and cancer. Indeed, Murgai et al. (30) recently demonstrated that KLF4-dependent changes in SMC phenotype and function, including SMC deposition of fibronectin, are critical for premetastatic niche formation in mouse models of lung cancer. Much like in the setting of atherosclerosis, the KLF4 dependence of premetastatic niche formation in mouse models of lung cancer is likely a maladaptive function of Klf4 in SMCs.

Surprisingly, our data suggest that Klf4 is required for the maintenance of perivascular coverage at baseline. Within 2 wk of the last tamoxifen injection, SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ mice already have developed gaps in eYFP+ coverage, suggesting that microvascular SMCs have a higher turnover rate than previously thought and that the source of their normal replacement cells is preexisting, lineage-traced SMCs through a KLF4-dependent process. Our KLF4 ChIP-Seq implicates several key SMC signaling pathways, including PDGF and FGF, not only as being KLF4 targets but also as having an important role in the maintenance of continuous SMC coverage (Fig. 6B). When KLF4 is lost, these pathways become dysregulated. However, the direction of change is unclear, as KLF4 has been shown to act as both a repressor and an activator of gene transcription (8, 36). One potential explanation for the loss of eYFP+ SMC coverage in SMC eYFP+/+Klf4Δ/Δ mice is a dysregulation of potent mitogen pathways that results in migration of SMCs away from the vessel. This would appear to be unlikely, as we saw no eYFP+ cells in the interstitium, away from blood vessels, in the retinas and spinotrapezius muscle of our knockout mice. Ultimately, Klf4 loss in SMCs results in activation of a compensatory process wherein a non-SMC, nonmyeloid source of SMC progenitors fills the gaps in perivascular coverage and activates SMC marker genes, including Acta2 and Myh11. Although these replacement cells have activated the SMC gene expression profile, they may not be perfect replacements, as we are able to detect functional changes in vessel diameter by pressure myography as well as an increase in vessel permeability. However, we cannot ascribe the functional changes simply to these replacement cells. Rather, we can only conclude that the functional changes are the overall consequence of initial loss of Klf4 exclusively in SMCs plus any possible downstream secondary effects. Given the hundreds of putative KLF4 target genes in SMCs identified in our KLF4 ChIP-Seq analyses, the underlying mechanisms responsible for the functional changes in resistance vessels are likely to be extraordinarily complex.

The source of the MYH11+ACTA2+ replacement cells remains unknown, although we know it is not the bone marrow (Fig. 7E). One possible source would be an unlabeled MYH11− SMC progenitor cell. This would be difficult to investigate, as no marker is known to label such a population. Other possible sources of replacement cells include endothelial cells undergoing endothelial-to-mesenchymal transitions and SCA1+ adventitial stem cells (6, 7, 32). Unfortunately, these possibilities cannot be tested, as lineage tracing of these populations would require a Cre recombinase-independent system, since we require use of the Myh11ERT2-Cre lineage tracing and simultaneous Klf4 knockout systems to generate the gaps. There is also no definitive model system for rigorous lineage tracing of SCA1+ stem cell populations, since Sca1 is also expressed by numerous other cell types.

In conclusion, results of the present studies show that Klf4 has a previously unknown, crucial maintenance role within resistance vessels, in that its loss is associated with dilation of resistance vessels, reduced blood pressure, and development of cardiac dilation. Further studies are needed to identify the complex mechanisms by which Klf4 regulates SMC function within resistance vessels and the extent to which this process is conserved across species, including humans. Indeed, identification of unique KLF4 targets in atherosclerosis and cancer will be necessary for development of targeted treatment strategies to avoid disruption of the critical homeostatic role of Klf4 within baseline SMCs. In addition, based on recent genome association studies showing that Klf4 polymorphisms are highly associated with coronary artery disease (16), it will be important to determine how dysregulation of KLF4 expression might contribute to microvascular dysfunction associated with type 2 diabetes, metabolic disease, and obesity.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-HL-057353, R01-HL-135018, and R01-HL-132904 (to G. K. Owens), R01-HL-088554 (to B. E. Isakson), F32-HL-131399 (to M. E. Good), T32-HL-007284 (to R. M. Haskins, G. F. Alencar, and M. E. Good), and S10-RR-022582 (shared instrumentation) and American Heart Association Grants 14PRE20430020 (to R. M. Haskins), 12POST11630032 (to A. T. Nguyen), and 15PRE25730011 (to G. F. Alencar).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.M.H., A.T.N., A.L.K., and G.K.O. conceived and designed research; R.M.H., A.T.N., M.B., M.R.K.-G., K.B., and A.L.K. performed experiments; R.M.H., A.T.N., G.F.A., M.B., M.R.K.-G., and M.E.G. analyzed data; R.M.H., A.T.N., G.F.A., M.B., M.R.K.-G., M.E.G., B.E.I., and G.K.O. interpreted results of experiments; R.M.H. and G.F.A. prepared figures; R.M.H. drafted manuscript; R.M.H., A.T.N., G.F.A., M.B., M.R.K.-G., M.E.G., K.B., A.L.K., B.A.F., T.E.H., S.M.P., B.E.I., and G.K.O. edited and revised manuscript; R.M.H., A.T.N., G.F.A., M.B., M.R.K.-G., M.E.G., K.B., A.L.K., B.A.F., T.E.H., S.M.P., B.E.I., and G.K.O. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank M. Bevard and M. McCanna for histology expertise as well as M. Adli and J. Thorpe for assistance and expertise with the ChIP-Seq library preparation and preliminary read alignment. The authors acknowledge Y. Xu, B. Thornhill, S. Sathyanarayana, and J. Hossack for intellectual contributions and assistance at various points throughout the project.

Present address of M. Billaud: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15219.

Present address of K. Bottermann: Goethe-University Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt 60323, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander MR, Owens GK. Epigenetic control of smooth muscle cell differentiation and phenotypic switching in vascular development and disease. Annu Rev Physiol 74: 13–40, 2012. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrae J, Gallini R, Betsholtz C. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev 22: 1276–1312, 2008. doi: 10.1101/gad.1653708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armulik A, Genové G, Betsholtz C. Pericytes: developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev Cell 21: 193–215, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billaud M, Lohman AW, Straub AC, Parpaite T, Johnstone SR, Isakson BE. Characterization of the thoracodorsal artery: morphology and reactivity. Microcirculation 19: 360–372, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2012.00172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen PY, Qin L, Baeyens N, Li G, Afolabi T, Budatha M, Tellides G, Schwartz MA, Simons M. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition drives atherosclerosis progression. J Clin Invest 125: 4514–4528, 2015. doi: 10.1172/JCI82719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen PY, Qin L, Barnes C, Charisse K, Yi T, Zhang X, Ali R, Medina PP, Yu J, Slack FJ, Anderson DG, Kotelianski V, Wang F, Tellides G, Simons M. FGF regulates TGF-β signaling and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via control of let-7 miRNA expression. Cell Reports 2: 1684–1696, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherepanova OA, Gomez D, Shankman LS, Swiatlowska P, Williams J, Sarmento OF, Alencar GF, Hess DL, Bevard MH, Greene ES, Murgai M, Turner SD, Geng YJ, Bekiranov S, Connelly JJ, Tomilin A, Owens GK. Activation of the pluripotency factor OCT4 in smooth muscle cells is atheroprotective. Nat Med 22: 657–665, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nm.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dobaczewski M, Gonzalez-Quesada C, Frangogiannis NG. The extracellular matrix as a modulator of the inflammatory and reparative response following myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 504–511, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franklin SS, Gokhale SS, Chow VH, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, Mitchell GF, Wong ND. Does low diastolic blood pressure contribute to the risk of recurrent hypertensive cardiovascular disease events? The Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension 65: 299–305, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franklin SS, Lopez VA, Wong ND, Mitchell GF, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Levy D. Single versus combined blood pressure components and risk for cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 119: 243–250, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.797936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.French WJ, Creemers EE, Tallquist MD. Platelet-derived growth factor receptors direct vascular development independent of vascular smooth muscle cell function. Mol Cell Biol 28: 5646–5657, 2008. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00441-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez D, Shankman LS, Nguyen AT, Owens GK. Detection of histone modifications at specific gene loci in single cells in histological sections. Nat Methods 10: 171–177, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.González A, Ravassa S, Beaumont J, López B, Díez J. New targets to treat the structural remodeling of the myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol 58: 1833–1843, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guzman RJ, Abe K, Zarins CK. Flow-induced arterial enlargement is inhibited by suppression of nitric oxide synthase activity in vivo. Surgery 122: 273–279, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(97)90018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Harst P, Verweij N. Identification of 64 novel genetic loci provides an expanded view on the genetic architecture of coronary artery disease. Circ Res 122: 433–443, 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hicke L, Dunn R. Regulation of membrane protein transport by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 19: 141–172, 2003. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.154617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 4: 44–57, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwata H, Manabe I, Fujiu K, Yamamoto T, Takeda N, Eguchi K, Furuya A, Kuro-o M, Sata M, Nagai R. Bone marrow-derived cells contribute to vascular inflammation but do not differentiate into smooth muscle cell lineages. Circulation 122: 2048–2057, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.965202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanisicak O, Khalil H, Ivey MJ, Karch J, Maliken BD, Correll RN, Brody MJ, J Lin SC, Aronow BJ, Tallquist MD, Molkentin JD. Genetic lineage tracing defines myofibroblast origin and function in the injured heart. Nat Commun 7: 12260, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kannel WB, Wilson PWF, Nam BH, D’Agostino RB, Li J. A likely explanation for the J-curve of blood pressure cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol 94: 380–384, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly-Goss MR, Ning B, Bruce AC, Tavakol DN, Yi D, Hu S, Yates PA, Peirce SM. Dynamic, heterogeneous endothelial Tie2 expression and capillary blood flow during microvascular remodeling. Sci Rep 7: 9049, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08982-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klibanov AL, Rychak JJ, Yang WC, Alikhani S, Li B, Acton S, Lindner JR, Ley K, Kaul S. Targeted ultrasound contrast agent for molecular imaging of inflammation in high-shear flow. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 1: 259–266, 2006. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10: R25, 2009. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup . The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079, 2009. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y, Sinha S, McDonald OG, Shang Y, Hoofnagle MH, Owens GK. Kruppel-like factor 4 abrogates myocardin-induced activation of smooth muscle gene expression. J Biol Chem 280: 9719–9727, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long JZ, Svensson KJ, Tsai L, Zeng X, Roh HC, Kong X, Rao RR, Lou J, Lokurkar I, Baur W, Castellot JJ Jr, Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. A smooth muscle-like origin for beige adipocytes. Cell Metab 19: 810–820, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lubsen J, Wagener G, Kirwan B-A, de Brouwer S, Poole-Wilson PA; ACTION (A Coronary disease Trial Investigating Outcome with Nifedipine GITS) Investigators . Effect of long-acting nifedipine on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity in patients with symptomatic stable angina and hypertension: the ACTION trial. J Hypertens 23: 641–648, 2005. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000160223.94220.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Casagrande JT, Thomas PD. Large-scale gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system. Nat Protoc 8: 1551–1566, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murgai M, Ju W, Eason M, Kline J, Beury DW, Kaczanowska S, Miettinen MM, Kruhlak M, Lei H, Shern JF, Cherepanova OA, Owens GK, Kaplan RN. KLF4-dependent perivascular cell plasticity mediates pre-metastatic niche formation and metastasis. Nat Med 23: 1176–1190, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nm.4400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Aikawa E, Stangenberg L, Wurdinger T, Figueiredo J-L, Libby P, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J Exp Med 204: 3037–3047, 2007. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Passman JN, Dong XR, Wu S-P, Maguire CT, Hogan KA, Bautch VL, Majesky MW. A sonic hedgehog signaling domain in the arterial adventitia supports resident Sca1+ smooth muscle progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 9349–9354, 2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711382105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Protogerou AD, Safar ME, Iaria P, Safar H, Le Dudal K, Filipovsky J, Henry O, Ducimetière P, Blacher J. Diastolic blood pressure and mortality in the elderly with cardiovascular disease. Hypertension 50: 172–180, 2007. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26: 841–842, 2010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudic RD, Shesely EG, Maeda N, Smithies O, Segal SS, Sessa WC. Direct evidence for the importance of endothelium-derived nitric oxide in vascular remodeling. J Clin Invest 101: 731–736, 1998. doi: 10.1172/JCI1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salmon M, Gomez D, Greene E, Shankman L, Owens GK. Cooperative binding of KLF4, pELK-1, and HDAC2 to a G/C repressor element in the SM22α promoter mediates transcriptional silencing during SMC phenotypic switching in vivo. Circ Res 111: 685–696, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shankman LS, Gomez D, Cherepanova OA, Salmon M, Alencar GF, Haskins RM, Swiatlowska P, Newman AA, Greene ES, Straub AC, Isakson B, Randolph GJ, Owens GK. KLF4-dependent phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells has a key role in atherosclerotic plaque pathogenesis. Nat Med 21: 628–637, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nm.3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith CL, Baek ST, Sung CY, Tallquist MD. Epicardial-derived cell epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and fate specification require PDGF receptor signaling. Circ Res 108: e15–e26, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.235531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsagalou EP, Anastasiou-Nana M, Agapitos E, Gika A, Drakos SG, Terrovitis JV, Ntalianis A, Nanas JN. Depressed coronary flow reserve is associated with decreased myocardial capillary density in patients with heart failure due to idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 52: 1391–1398, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39a.van den Borne SWM, Diez J, Blankesteijn WM, Verjans J, Hofstra L, Narula J. Myocardial remodeling after infarction: the role of myofibroblasts. Nat Rev Cardiol 7: 30–37, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vannella KM, Wynn TA. Mechanisms of organ injury and repair by macrophages. Annu Rev Physiol 79: 593–617, 2017. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei K, Jayaweera AR, Firoozan S, Linka A, Skyba DM, Kaul S. Quantification of myocardial blood flow with ultrasound-induced destruction of microbubbles administered as a constant venous infusion. Circulation 97: 473–483, 1998. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.97.5.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshida T, Gan Q, Owens GK. Kruppel-like factor 4, Elk-1, and histone deacetylases cooperatively suppress smooth muscle cell differentiation markers in response to oxidized phospholipids. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C1175–C1182, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00288.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshida T, Kaestner KH, Owens GK. Conditional deletion of Krüppel-like factor 4 delays downregulation of smooth muscle cell differentiation markers but accelerates neointimal formation following vascular injury. Circ Res 102: 1548–1557, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, Liu XS. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol 9: R137, 2008. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]