Abstract

Intestinal ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) occurs in various clinical settings, such as transplantation, acute mesenteric arterial occlusion, trauma, and shock. I/R injury causes severe systemic inflammation, leading to multiple organ dysfunction associated with high mortality. The ubiquitin proteasome pathway has been indicated in the regulation of inflammation, particularly through the NF-κB signaling pathway. PYR-41 is a small molecular compound that selectively inhibits ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1. A mouse model of intestinal I/R injury by clamping the superior mesenteric artery for 45 min was performed to evaluate the effect of PYR-41 treatment on organ injury and inflammation. PYR-41 was administered intravenously at the beginning of reperfusion. Blood and organ tissues were harvested at 4 h after reperfusion. PYR-41 treatment improved the morphological structure of gut and lung after I/R, as judged by hematoxylin and eosin staining. It also reduced the number of apoptotic terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end-labeling-positive cells and caspase-3 activity in the organs. PYR-41 treatment decreased the expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β as well as chemokines keratinocyte chemoattractant and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 in the gut and lung, which leads to inhibition of neutrophils infiltrating into these organs. The serum levels of IL-6, aspartate aminotransferase, and lactate dehydrogenase were reduced by the treatment. The IκB degradation in the gut increased after I/R was inhibited by PYR-41 treatment. Thus, ubiquitination may be a potential therapeutic target for treating patients suffering from intestinal I/R.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Excessive inflammation contributes to organ injury from intestinal ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) in many clinical conditions. NF-κB signaling is very important in regulating inflammatory response. In an experimental model of gut I/R injury, we demonstrate that administration of a pharmacological inhibitor of ubiquitination process attenuates NF-κB activation, leading to reduction of inflammation, tissue damage, and apoptosis in the gut and lungs. Therefore, ubiquitination process may serve as a therapeutic target for treating patients with intestinal I/R injury.

Keywords: gut ischemia-reperfusion, inflammation, inhibitor, organ injury, ubiquitination

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) is considered to be a major clinical problem during abdominal and thoracic vascular surgery, small intestine transplantation, hemorrhagic shock, and surgery using cardiopulmonary bypass, leading to high morbidity and mortality (2, 7, 48). Multiple organ failure (MOF), including acute lung injury (ALI), is a common complication that occurs after intestinal I/R (10, 13, 28). MOF can result from a systemic inflammatory response due to the release of proinflammatory cytokines and bacteria-derived endotoxin from reperfused intestinal tissues after ischemic insult (12, 13). Currently, only a limited number of pharmacological treatment options are available to provide some benefits in patients with intestinal I/R. Because inflammation plays a role in the damage caused by intestinal I/R, targeting or controlling the inflammatory progression will be very crucial to reduce the organ injury and mortality after intestinal I/R.

NF-κB signaling is one of the key pathways that regulates the production of proinflammatory mediators, such as cytokines and chemokines, in response to various stimuli (22, 50). Under unstimulated conditions, transcription factor NF-κB is located in the cytoplasm and binds to its inhibitor molecule IκB (31). When extracellular stimuli engage with the receptors, IκB will be degraded to release NF-κB. NF-κB next translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and binds to the promoter region of the targeted genes to increase their expression (31). Moreover, the NF-κB pathway plays a central role in the pathogenesis of various human diseases (6) and thus is widely considered as an attractive therapeutic target for drug development. However, despite tremendous efforts devoted by the pharmaceutical industry to develop a specific NF-κB inhibitor, none has been clinically approved because of the dose-limiting toxicities (4). Instead, efforts have switched to target other molecules involved in regulating the NF-κB signaling pathway (4). During the NF-κB activation process, preventing the degradation of IκB can be a control point to inhibit NF-κB activity for proinflammatory cytokine production.

IκB degradation is regulated by the ubiquitin proteasome pathway (UPP) (23). The UPP, consisting of ubiquitination and degradation steps, is essential in controlling protein turnover in cells (9, 19). The ubiquitination step requires a series of enzymatic activities to attach a small ubiquitin protein on the target protein (19). First, the E1 enzyme activates ubiquitin for conjugation and transfers it to an E2 enzyme. The E2 enzyme interacts with an E3 enzyme to transfer the ubiquitin to the target protein. When the target proteins are ubiquitinated, they will be recognized by the proteasome enzyme complex for degradation (9). Therefore, targeting the ubiquitination process to prevent IκB degradation may be a way to inhibit NF-κB activation.

In this study, we hypothesized that inhibition of the ubiquitination process could attenuate inflammation and organ damage after intestinal I/R. A small cell-permeable chemical compound, 4[4-(5-nitro-furan-2-ylmethylene)-3,dioxo-pyrazolidin-1-yl]-benzoic acid ethyl ester (PYR-41), is a selective inhibitor of the E1 enzyme (47). By using a mouse model of gut I/R injury, we first examined the effect of PYR-41 treatment on gut injury, apoptosis, and inflammation. We also examined the expression of IκB in the gut and intestinal epithelial cells after I/R and hypoxia/reoxygenation stresses, respectively. We then demonstrated the effect of PYR-41 treatment on systemic inflammation and serum organ injury markers after gut I/R. Finally, we examined the alteration of lung injury, apoptosis, and inflammation after gut I/R by PYR-41 treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal model of gut I/R injury.

Male C57BL/6 mice (20–25 g; Taconic, Albany, NY) were housed in a temperature-controlled room on a 12-h:12-h light/dark cycle and fed Purina chow diet. Mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation, and the abdomen was shaved and washed with 10% povidone iodine. An upper midline laparotomy was performed to expose the abdomen, and the superior mesenteric artery (SMO) was occluded by fastening with 4-0 silk suture and a PE-50 catheter. Cessation of blood flow to the intestines was judged by color changes to paleness of peripheral mesenteric vessels of the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. After 45 min, the SMO suture was removed, and mice were administered 5 mg/kg body wt of PYR-41 (Tocris, Park Ellisville, MO) or vehicle (20% DMSO in normal saline) by intravenous injection from the jugular vein at the beginning of reperfusion. After surgery, mice were resuscitated with 1 ml isotonic sodium chloride solution by subcutaneous injection. Sham animals underwent only midline laparotomy without gut I/R and treatment. At 4 h after reperfusion, blood, gut, and lung tissues were collected and stored at −80°C for further analyses. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines for the use of experimental animals by the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Feinstein Institute of Medical Research.

Cell culture and hypoxia exposure.

Rat intestinal epithelial cells (IEC)-6 obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) were cultured with DMEM media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% glutamate at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. IEC-6 cells were subjected to hypoxia in a sealed modular incubator chamber (Billups-Rothenberg, Delmar, CA) with 94% N2-5% CO2-1% O2 at 37°C for 20 h. After hypoxia exposure, cells were reoxygenated in a regular CO2 incubator for another 20 h.

Histological analysis.

Gut and lung tissues were fixed in 10% formalin and then embedded in paraffin. Tissue blocks were sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E). Morphological examination of these tissues was evaluated under a light microscope in a blinded manner. The mucosal damage of the gut was quantified by using the score of Park et al. (35) as follows: 0, normal mucosa; 1, subepithelial space at villus tip; 2, more extended subepithelial space; 3, epithelial lifting along villus sides; 4, denuded villi; 5, loss of villus tissue; 6, crypt layer infarction; 7, transmucosal infarction; and 8, transmural infarction. The severity of lung injury was judged by a semiquantitative scoring system according to the following pathological features (29): 1) focal alveolar membrane thickening, 2) capillary congestion, 3) intra-alveolar hemorrhage, 4) interstitial neutrophil infiltration, and 5) intra-alveolar neutrophil infiltration. Each feature was scored from 0 to 3 based on its absence (0) or presence to a mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3) degree, and a cumulative total histology score was determined.

Measurement of myeloperoxidase activity.

Gut and lung tissues were homogenized in potassium phosphate buffer containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide. After centrifugation the supernatant was diluted in a reaction solution, and the rate of change in optimal density for 2 min was measured at 460 nm to calculate myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (8).

Real-time PCR analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from gut and lung tissues using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and was reverse transcribed into cDNA using murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). A PCR reaction was carried out in 25 μl of a final volume containing 0.08 μmol of each forward and reverse primer, cDNA, and 12.5 μl SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Amplification was conducted in an Applied Biosystems 7300 real-time PCR machine under the thermal profile of 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. The level of mouse β-actin mRNA was used for normalization. Relative expression of mRNA was expressed as the fold change compared with the sham tissues. The sequences for the primers used in this study are as follows: mouse IL-6, 5′-CCGGAGAGGAGACTTCACAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGAATTGCCATTGCACAAC-3′ (reverse); mouse IL-1β, 5′-CAGGATGAGGACATGAGCACC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTCTGCAGACTCAAACTCCAC-3′ (reverse); mouse keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC), 5′-GCTGGGATTCACCTCAAGAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACAGGTGCCATCAGAGCAGT-3′ (reverse); mouse macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2), 5′-CCCTGGTTCAGAAAATCATCCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTCCTCCTTTCCAGGTCAGT-3′ (reverse); and mouse β-actin, 5′-CGTGAAAAGATGACCCAGATCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGGTACGACCAGAGGCATACAG-3′ (reverse).

Measurements of cytokines and serum organ injury markers.

IL-6 and IL-1β were quantified by using specific mouse ELISA kits from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were measured using assay kits from Pointe Scientific (Lincoln Park, MI).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end-labeling assay.

Gut and lung tissue slides were dewaxed and incubated with proteinase K. Slides were stained using a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) kit from Roche (Indianapolis, IN), counterstained with propidium iodide (red fluorescence), and examined under a fluorescence microscope. Apoptotic cells appeared green under a fluorescence microscope and were counted at ×200 magnification in 10 visual fields/section. The average of the number of apoptotic cells/field was calculated.

Western blotting analysis.

Gut and lung tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer, concisting of 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 120 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) by sonication. Total tissue homogenate and cell lysate were fractionated on Bis-Tris gels (4–12%) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Nitrocellulose membranes were blocked by incubation in 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) containing 10% nonfat dry milk for 1 h. Membranes were incubated with anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), anti-IκB (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), or anti-β-actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) antibodies overnight at 4°C. After wash with TBST, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Specific proteins were visualized by using Pierce ECL 2 Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Southfield, MI). Band densities were determined by using a Bio-Rad image system.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SE and compared with one-way analysis of variance and the Student-Newman-Keul's test for multiple group analyses. Differences in values were considered significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Administration of PYR-41 attenuates gut damage after gut I/R.

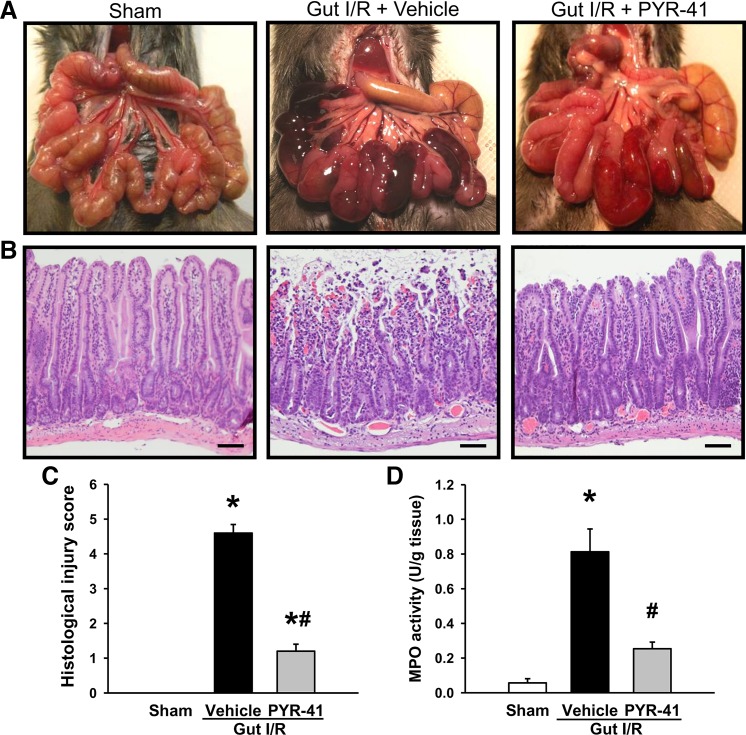

We first examined the gross appearance of intestine in the mice at 4 h after gut I/R. The intestine in the vehicle-treated mice exhibited vascular congestion as indicated in the dark areas, where it was not observed in sham mice (Fig. 1A). The darkness of the congested areas was much lighter in the PYR-41-treated mice than those in vehicle (Fig. 1A). We then further performed histological examination of the intestines in these mice. In contrast to sham, the integrity at the top of villi was lost in the vehicle-treated mice, where it was much well persevered in the PYR-41-treated mice (Fig. 1B). The severity of gut injury among these groups was quantified by Park et al.’s score system as described in materials and methods (35). The gut injury score of vehicle-treated mice reached 4.6, whereas it was reduced by 74% to 1.2 with PYR-41 treatment (Fig. 1C). To validate neutrophil infiltration, we measured MPO activity in the gut. As shown in Fig. 1D, MPO activity in the gut of vehicle-treated mice was markedly increased compared with sham. There was a 69% reduction on MPO activity in the PYR-41-treated group compared with vehicle (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Administration of PYR-41 attenuates intestine damage in the mice after gut ischemia-reperfusion (I/R). Mice were subjected to gut ischemia for 45 min and administered vehicle (20% DMSO in normal saline) or PYR-41 (5 mg/kg) at the beginning of reperfusion. At 4 h after reperfusion, mice were euthanized, and intestines were harvested. A: representative images for the gross appearance of the gut in different groups before dissection. B: representative images of inessential tissues stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) from different groups and examined under light microscopy at ×200 magnification. Scale bar, 100 µm. C: histological injury scores (Park’s score) of the gut in different groups were quantified as described in materials and methods. D: myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in the intestine of each group was determined spectrophotometrically. Data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5/group). P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vehicle (#).

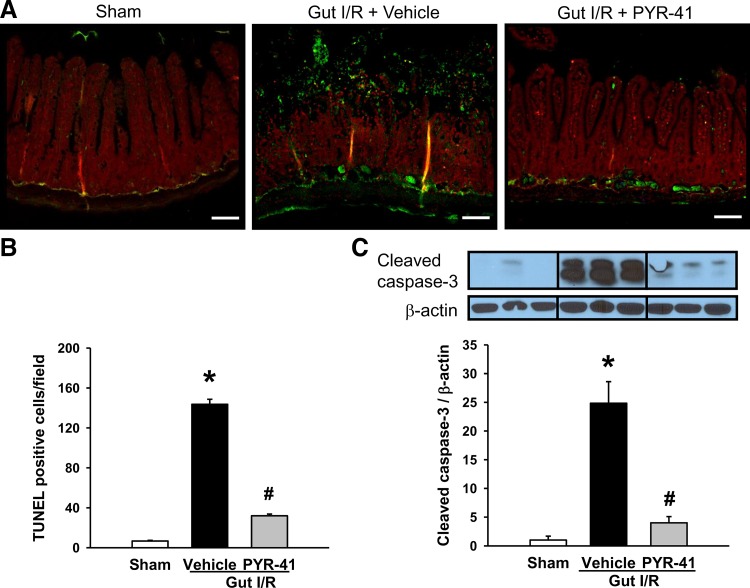

Administration of PYR-41 decreases apoptosis in the gut after gut I/R.

To examine the effect of PYR-41 on apoptosis in the gut after gut I/R, we performed a TUNEL assay to detect DNA fragmentation by immunohistochemistry. The apoptotic cells shown with green fluorescence were well detected in the gut of vehicle-treated mice but rarely spotted in sham and more weakly shown in PYR-41-treated mice (Fig. 2A). After quantification, the number of apoptotic cells in the vehicle-treated group reached 144 cells/field and reduced to 32 cells/field with PYR-41 treatment (Fig. 2B). To further validate the occurrence of apoptosis, we examined the expression of cleaved caspase-3 expression by Western blot analysis. Like TUNEL assay, the levels of cleaved caspase-3 were dramatically increased after gut I/R (Fig. 2C). In contrast, cleaved caspase-3 levels with PYR-41 treatment were reduced to levels comparable with those of sham (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Administration of PYR-41 inhibits apoptosis in the gut after gut ischemia-reperfusion (I/R). Mice were subjected to gut ischemia for 45 min and administered vehicle (20% DMSO in normal saline) or PYR-41 (5 mg/kg) at the beginning of reperfusion. At 4 h after reperfusion, intestines were harvested. A: representative images of the inessential tissues in different groups subjected to terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) staining (green fluorescence) and counterstaining with propidium iodide (red fluorescence). ×200 Magnification. Scale bar, 100 µm. B: graphical representation of TUNEL-positive cells averaged over 10 microscopic fields/animal in each group. C: expression of cleaved caspase-3 in the gut of each group was determined by Western blotting. Representative blots are shown on top. Blots were scanned and quantified with densitometry. Protein levels in the sham group are designated as 1 for comparison. Data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5/group). P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vehicle (#).

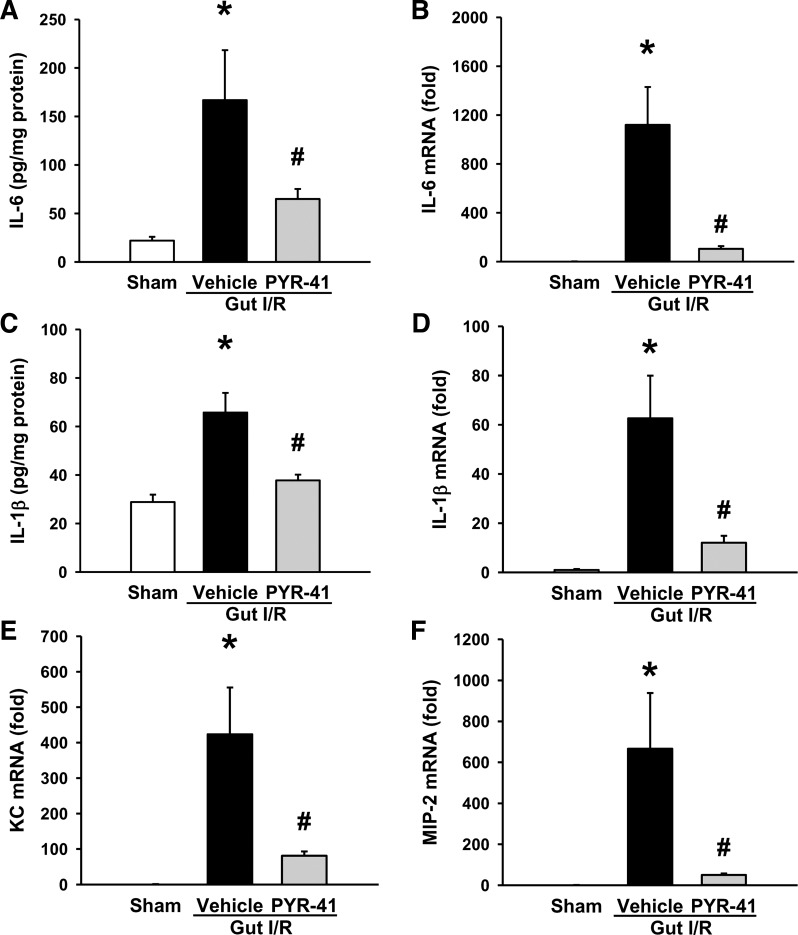

Administration of PYR-41 inhibits inflammation in the gut after gut I/R.

To determine the effect of PYR-41 on inflammation, we measured several proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the gut at 4 h after gut I/R. Protein and mRNA levels of gut IL-6 in vehicle-treated mice were increased by 7.9- and 1,120-fold, respectively, compared with sham (Fig. 3, A and B). With PYR-41 treatment, their levels were decreased by 61 and 91%, respectively, compared with vehicle (Fig. 3, A and B). Similarly, the protein and mRNA levels of gut IL-1β were significantly elevated after gut I/R, whereas their levels were reduced by 43 and 81%, respectively, with PYR-41 treatment (Fig. 3, C and D). The mRNA levels of gut KC and MIP-2, chemoattractants for neutrophils, were dramatically increased by 423- and 667-fold in vehicle-treated mice compared with sham (Fig. 3, E and F). Administration of PYR-41 resulted in 81 and 92% reduction in the expression of gut KC and MIP-2, respectively (Fig. 3, E and F).

Fig. 3.

Administration of PYR-41 reduces the expression of proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine in the gut after gut ischemia-reperfusion (I/R). Mice were subjected to gut ischemia for 45 min and administered vehicle (20% DMSO in normal saline) or PYR-41 (5 mg/kg) at the beginning of reperfusion. At 4 h after reperfusion, intestines were harvested. Total protein from the gut tissue was isolated to measure protein levels of IL-6 (A) and IL-1β (C) by ELISA. Total RNA from the gut tissue was isolated to determine the mRNA levels of IL-6 (B), IL-1β (D), keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC, E), and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2, F) by qPCR. mRNA levels in the sham group are designated as 1 for comparison. Data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5/group). P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vehicle (#).

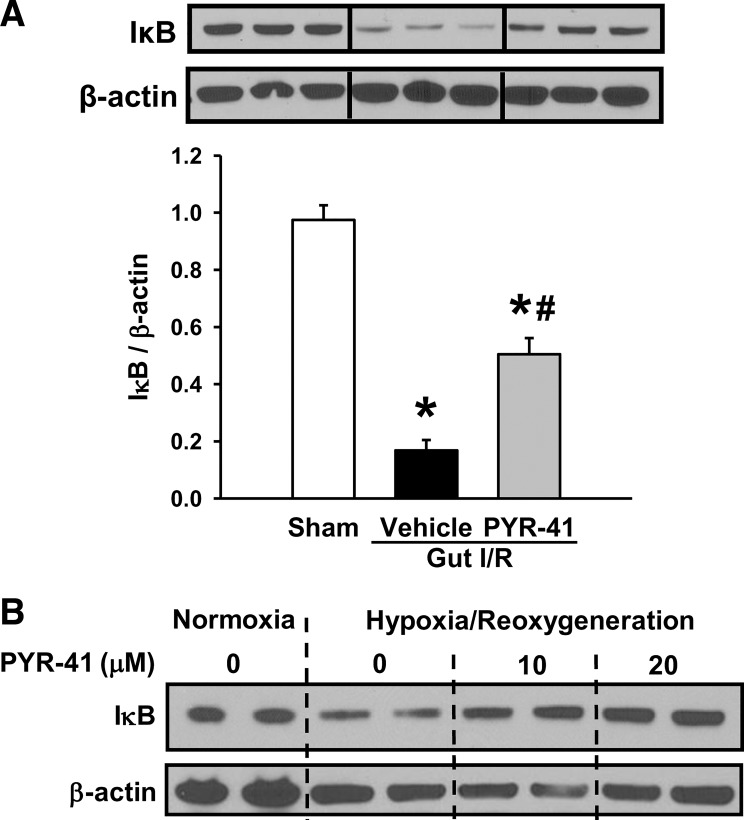

PYR-41 inhibits NF-κB activation signaling in the gut.

After demonstrating the attenuation of inflammation in the gut by PYR-41 treatment, we then examined the effect of PYR-41 on activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. The protein levels of IκB, an NF-κB inhibitor, were significantly decreased in vehicle-treated mice compared with sham (Fig. 4A). PYR-41 treatment prevented the degradation of IκB in the gut after gut I/R (Fig. 4A). To test whether PYR-41 had a direct effect on regulating NF-κB signaling in gut epithelial cells, we exposed IEC-6 cells to hypoxia, followed by reoxygenation in the absence or presence of PYR-41. As shown in Fig. 4B, IκB protein was degraded in IEC-6 cells exposed to hypoxia. However, in the presence of PYR-41 at 20 µM, the expression levels of IκB were comparable to those grown under normoxia conditions (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Administration of PYR-41 inhibits IκB degradation after stimulus. A: mice were subjected to gut ischemia for 45 min and administered vehicle (20% DMSO in normal saline) or PYR-41 (5 mg/kg) at the beginning of reperfusion. At 4 h after reperfusion, intestines were harvested. B: cultured intestinal epithelial cells (IEC)-6 intestinal epithelial cells were subjected to hypoxia at 1% O2 for 20 h followed by reoxygenation for another 20 h in the presence of 10 or 20 µM PYR-41. Total protein from the gut tissues (same as Fig. 2C) and cells was isolated to determine the protein levels of IκB by Western blotting. Blots were scanned and quantified with densitometry. Protein levels in the sham group are designated as 1 for comparison. Data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5/group). P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vehicle (#).

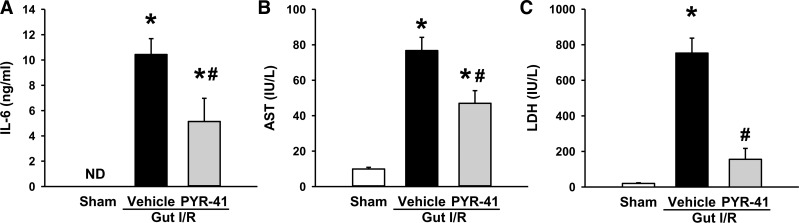

Administration of PYR-401 decreases systemic inflammation and organ injury markers after gut I/R.

After identifying the inhibition of PYR-41 treatment on gut inflammation, we examined its effect on systemic inflammation. As expected, serum levels of IL-6 were dramatically increased to 10.5 ng/ml after gut I/R, whereas they were nondetectable in sham (Fig. 5A). With PYR-41 treatment, serum IL-6 levels were decreased by 51% compared with vehicle (Fig. 5A). We also evaluated the severity of overall organ injury by measuring serum organ injury markers, AST and LDH. After gut I/R, the serum levels of AST and LDH were increased by 7.7- and 37-fold, respectively, compared with sham (Fig. 5, B and C). PYR-41 treatment resulted in a reduction of AST and LDH levels by 39 and 79%, respectively, compared with vehicle (Fig. 5B and C).

Fig. 5.

Administration of PYR-41 decreased serum levels of proinflammatory cytokine and organ injury markers in the mice after gut ischemia-reperfusion (I/R). Mice were subjected to gut ischemia for 45 min and administered vehicle (20% DMSO in normal saline) or PYR-41 (5 mg/kg) at the beginning of reperfusion. At 4 h after reperfusion, blood was collected. Protein levels of IL-6 (A) were measured by ELISA. Serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST, B) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, C) were determined by an enzymatic method. Data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5/group). P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vehicle (#). ND, nondetectable.

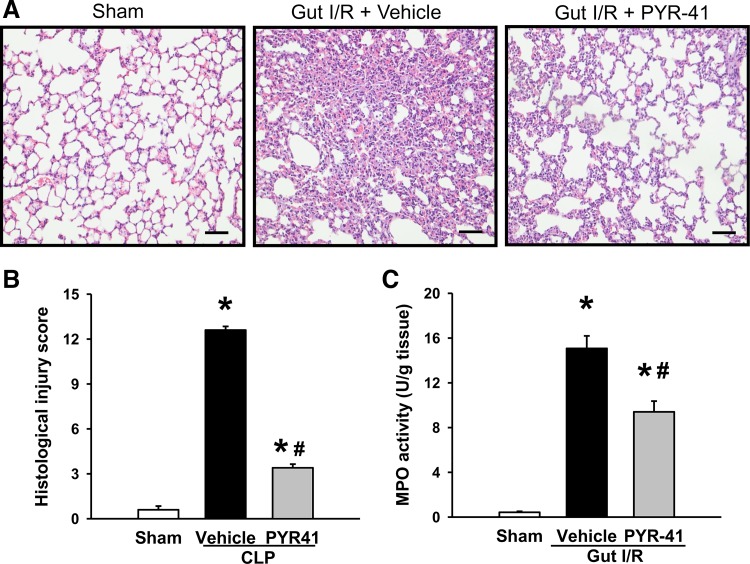

Administration of PYR-41 attenuates lung damage after gut I/R.

Lung is regarded as the most vulnerable remote organ to be damaged after gut I/R (25, 28). Lung tissues from vehicle-treated mice showed substantial morphological changes, including alveolar collapse, edema, hemorrhage, and infiltration of inflammatory cells, compared with sham (Fig. 6A). In contrast, administration of PYR-41 reduced the microscopic deterioration compared with the vehicle group (Fig. 6A). By semiquantification as described in materials and methods, the lung histological injury score in the vehicle-treated group reached to 12.6, whereas it was reduced by 73% to 3.4 with PYR-41 treatment (Fig. 6B). Correspondingly, lung MPO activity in vehicle-treated mice was increased by 38-fold compared with sham, whereas it was decreased by 37% in PYR-41-treated mice compared with vehicle (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Administration of PYR-41 attenuates lung damage in mice after gut ischemia-reperfusion (I/R). Mice were subjected to gut ischemia for 45 min and administered vehicle (20% DMSO in normal saline) or PYR-41 (5 mg/kg) at the beginning of reperfusion. At 4 h after reperfusion, lungs were harvested. A: representative images of lung tissues stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) from different groups and examined under light microscopy at ×200 magnification. Scale bar, 100 µm. B: histological injury scores of the lung in different groups were quantified as described in materials and methods. C: myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in the lung of each group was determined spectrophotometrically. Data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5/group). P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vehicle (#).

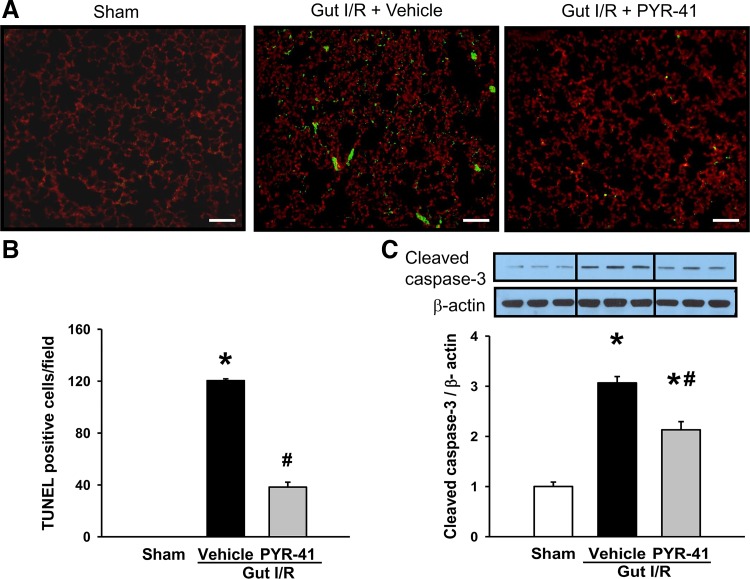

Administration of PYR-41 inhibits apoptosis in the lungs after gut I/R.

By performing the TUNEL assay on lung tissues at 4 h after gut I/R, many green fluorescent cells were observed in vehicle-treated mice, whereas they were not detected in sham (Fig. 7A). Lung tissues of the PYR-41-treated mice exhibited much less green fluorescent cells than vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 7A). By counting green fluorescent cells per field, the number of apoptotic cells in the lungs of the PYR-41-treated mice was decreased by 68% compared with the vehicle (Fig. 7B). The expression of cleaved caspase-3, as determined by Western blot analysis, was increased by 3.1-fold in vehicle-treated mice compared with sham, whereas it was decreased by 32% in PYR-41-treated mice compared with vehicle (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

Administration of PYR-41 inhibits apoptosis in the lungs after gut ischemia-reperfusion (I/R). Mice were subjected to gut ischemia for 45 min and administered vehicle (20% DMSO in normal saline) or PYR-41 (5 mg/kg) at the beginning of reperfusion. At 4 h after reperfusion, lungs were harvested. A: representative images of lung tissues in different groups subjected to terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) staining (green fluorescence) and counterstaining with propidium iodide (red fluorescence). ×200 Magnification. Scale bar, 100 µm. B: graphical representation of TUNEL-positive cells averaged over 10 microscopic fields/animal in each group. C: expression of cleaved caspase-3 in the lung of each group was determined by Western blotting. Representative blots are shown on top. Blots were scanned and quantified with densitometry. Protein levels in the sham group are designated as 1 for comparison. Data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5/group). P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vehicle (#).

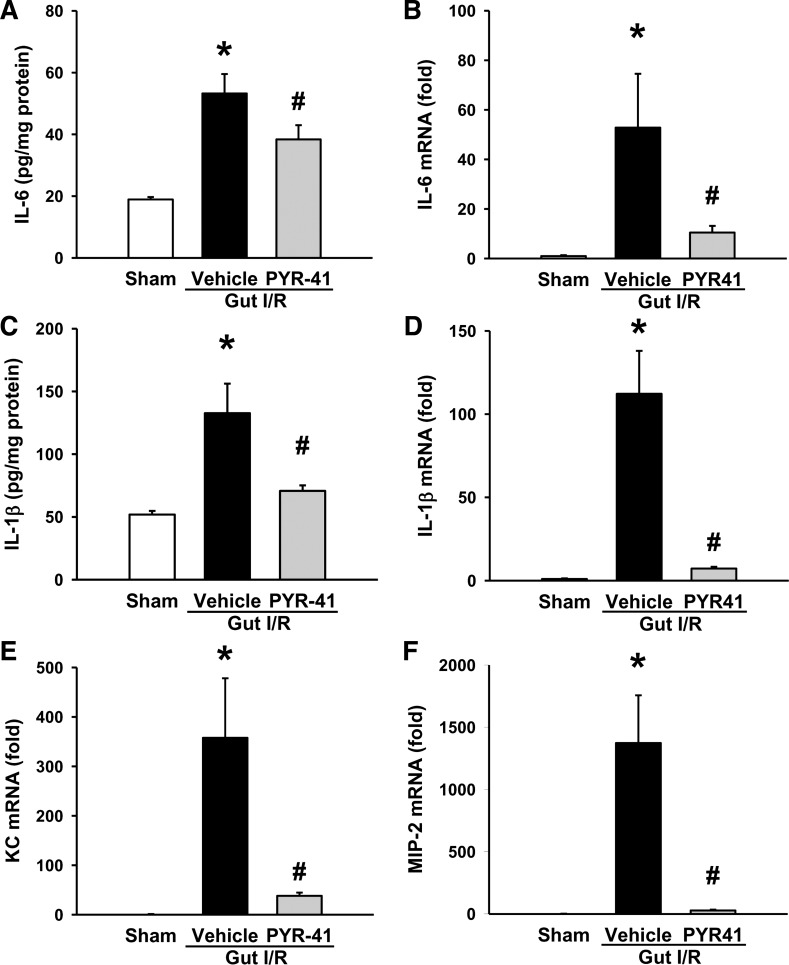

Administration of PYR-41 inhibits inflammation in the lungs after gut I/R.

We also examined lung inflammation at 4 h after gut I/R. The protein and mRNA levels of lung IL-6 were increased by 2.8- and 53-fold, respectively, after gut I/R (Fig. 8, A and B). PYR-41 treatment resulted in a reduction by 28 and 80%, respectively, compared with vehicle (Fig. 8, A and B). The protein and mRNA levels of lung IL-1β were also significantly elevated after gut I/R, whereas their levels were reduced by 47 and 94%, respectively, with PYR-41 treatment (Fig. 8, C and D). mRNA levels of lung KC and MIP-2 were dramatically increased by 358- and 1,373-fold, respectively, in vehicle-treated mice compared with sham (Fig. 8, E and F). Administration of PYR-41 resulted in 89 and 98% reduction in the expression of lung KC and MIP-2, respectively (Fig. 8, E and F).

Fig. 8.

Administration of PYR-41 reduces the expression of proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine in the lungs after gut ischemia-reperfusion (I/R). Mice were subjected to gut ischemia for 45 min and administered vehicle (20% DMSO in normal saline) or PYR-41 (5 mg/kg) at the beginning of reperfusion. At 4 h after reperfusion, lungs were harvested. Total protein from the lung tissue was isolated to measure the protein levels of IL-6 (A) and IL-1β (C) by ELISA. Total RNA from the lung tissue was isolated to determine mRNA levels of IL-6 (B), IL-1β (D), keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC, E), and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2, F) by qPCR. mRNA levels in the sham group are designated as 1 for comparison. Data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5/group). P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vehicle (#).

DISCUSSION

Intestinal ischemia often occurs in many clinical conditions after surgery. Following ischemia, the reperfusion stage can cause even more damage than the ischemia itself (36). The pathophysiology of I/R is complex. It starts with the lack of oxygen and nutrients, followed by mass generation of oxidative stress and inflammation, ultimately leading to cellular death and organ damage (24). In this study, we examined whether targeting ubiquitination, a process of controlling NF-κB activation, can be beneficial in reducing organ injury and inflammation under intestinal I/R injury. We have treated the mice that underwent gut I/R with PYR-41, an inhibitor of E1 enzyme for the initiation of ubiquitination. The results show that PYR-41 treatment improves the integrity of gut morphological structure and reduces apoptosis and inflammation in mice after gut I/R. We have validated the attenuation of IκB degradation in the gut by PYR-41 treatment. We have also shown that PYR-41 treatment decreases serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines and organ injury markers. We have further demonstrated that tissue damage, apoptosis, and inflammation in the lungs of the mice after gut I/R are reduced by PYR-41 treatment. PYR-41 is the first E1 inhibitor to be identified (47). Subsequently, PYZD-4409 (45) and NSC-624206 (44) are also discovered as E1 inhibitors. However, PYR-41 has a lower IC50 and thus is more potent than the other two compounds (44, 45). Therefore, PYR-41 is selected in this proof-of-concept study to demonstrate that E1 is a potential target for treating intestinal I/R injury.

In this mouse model, gut I/R causes the rupture of the mucosa barrier, as shown in histological H&E staining, with an association of increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and IL-1β, in the gut. Early inflammation has been indicated as a contributing factor for organ injury and dysfunction in I/R injuries, trauma, and sepsis (3, 38). With PYR-41 treatment, the protein levels of IL-6 and IL-1β in the gut of the mice are significantly decreased after gut I/R, which correlates with the improvement of gut morphology. Examining the change in expression of IL-6 and IL-1β mRNA with PYR-41 treatment clearly indicates that the change in levels of these two cytokines is regulated at the transcriptional level. The promoter regions of IL-6 and IL-1β genes contain NF-κB-binding sites (42), suggesting that attenuation of the expression of these two cytokines is mediated through the NF-κB signaling pathway. In the Western blot analysis, expression of IκB, an inhibitor of NF-κB, is dramatically reduced in the gut after I/R and rescued by PYR-41 treatment. In the in vitro study, we also demonstrated that degradation of IκB in the intestinal epithelial cells, which is activated by hypoxia/reoxygenation, can be inhibited by PYR-41. This result is consistent with the previous study showed that PYR-41 prevented the degradation of IκB in HeLa cells stimulated with IL-1α and 2B4 T cell hybridoma cells stimulated with TNF-α (47). However, the detailed mechanisms by which PYR-41 inhibits the ubiquitination of IκB in IEC-6 cells and nuclear translocation of NF-κB in gut tissues need further investigation. Although we did not examine the effect of PYR-41 on cytokine expression in IEC-6 cells, we previously demonstrated that PYR-41 inhibited the expression of proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α in macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide in a dose-dependent manner (26). Taken together, these results indicate that targeting ubiquitination by PYR-41 inhibits NF-κB activation and results in reduction of proinflammatory cytokine expression in the gut after I/R.

When neutrophils are recruited to the inflamed organs, these activated neutrophils will release proteolytic enzymes and reactive oxygen species to eradicate invading pathogens (20). However, excessive release of these molecules from neutrophils will also cause extravascular tissue damage and contribute to multiple organ failure and lethality (1). In analyzing the gut tissues, we have detected a marked increase of MPO activity, a marker of neutrophils (39). PYR-41 treatment can effectively lower the amount of neutrophils entering the gut. The migration of neutrophils to the tissue is promoted by chemokines (18). We have shown that the expression of chemokines KC and MIP-2 in the gut increases after I/R, whereas PYR-41 treatment inhibits their expression. The expression of KC and MIP-2 can be regulated at the transcriptional level by NF-κB (33). Consistently, both proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines as downstream targets of the NF-κB signaling pathway are attenuated by PYR-41 treatment.

As we have observed the disruption of the mucosa barrier in the gut after I/R, it can result in bacterial translocation (41). In addition, the cell injury induced by I/R can also release intracellular molecules as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) (21). Bacteria and DAMPs serve as stimuli to provoke inflammation in the host (27, 32). We have observed an increase of proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 in serum. Macrophages are the major cell type to produce proinflammatory cytokines. The reduction of serum IL-6 after I/R by PYR-41 treatment can be because of its protective effect on the gut to prevent bacterial translocation and DAMP release and inhibit NF-κB activation in macrophages. To check the association between hyperinflammation and multiple organ injury, we also measured the serum levels of AST and LDH. PYR-41 treatment also reduces the levels of these two organ injury markers in the mice after gut I/R.

For the distant organ injury induced by gut I/R, we have focused on the lung. As in the gut, we first observed the beneficial effect of PYR-41 treatment on the improvement of the integrity of lung morphology. We then examined the effect of PYR-41 treatment on inflammation in the lungs. The expression of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and IL-1β, as well as chemokines, KC and MIP-2, is inhibited by PYR-41 treatment. Such inhibition also links to the reduction of MPO activity in the lungs. Apoptosis is another contributing factor for organ damage (14). The mechanism of triggering apoptosis can also be induced by proinflammatory cytokines (5). By using TUNEL assay and measuring cleaved caspase-3 expression, the results clearly indicate that apoptosis occurred in the gut and lung of mice after gut I/R. PYR-41 treatment decreases the number of apoptotic cells in these two organs after gut I/R, which may be through inhibiting the proinflammatory cytokine production. Inhibition of apoptosis as a strategy to lower organ injury has also shown positive effect in other ischemic conditions, such as heart (40), liver (46), and kidney (49). Although PYR-41 can induce apoptotic cell death in the transformed cells, the untransformed cells are relatively resistant (47). Similarly, PYZD-4409 inhibits the clonogenic growth of leukemia cells but does not reduce the growth of normal hematopoietic cells (45). Our previous study also shows that PYR-41 does not affect the cell viability of macrophages (26). However, with long time incubation, PYR-41 can affect cell survival (47).

Ubiquitination is an important process of posttranslational modification needed to maintain cellular homeostasis and to regulate various cellular functions. However, targeting enzymes involved in ubiquitination as a therapeutic approach has also been proposed in other inflammatory diseases such as obesity, insulin resistance, atherosclerosis, angiotensin II-induced cardiac inflammation, and asthma (11). In our previous study, we have reported that PYR-41 treatment can inhibit inflammatory response and improve survival in the animal model of sepsis (26). At the same token, the inhibition of the proteasome degradation step, another component of the UPP pathway, has also shown beneficial effect in other inflammatory-related disease conditions, such as lactacystin for renal and gut I/R injury (17, 43), bortezomib for renal I/R injury (15), bortezomib for liver transplantation (34), and MG-132 for sepsis (37) and inflammatory bowel disease (16). Because the UPP pathway is important for cell survival, the deleterious effects of its inhibition are a concern. To move a drug candidate forward, a series of rigorous toxicity tests in animals followed by clinical phase I safety and dose-escalation studies are required. The severity of deleterious effects may be minimized by the dosage and frequency of the drugs administered. Our finding provides a proof of concept that ubiquitination may be targeted for the drug development to treat intestinal I/R injury. With the approval of bortezomib by the Food and Drug Administration for treating multiple myeloma in patients (30), it is very encouraging in developing the drug candidates by targeting the UPP pathway.

In summary, PYR-41 treatment prevents IκB degradation to activate the NF-κB pathway, controlling inflammation in mice that underwent gut I/R. It also reduces tissue damage and apoptosis in the gut and lung. Therefore, targeting ubiquitination as a therapeutic strategy, like PYR-41, for treating patients with intestinal I/R warrants further development.

GRANTS

This study was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant R35-GM-118337 (to P. Wang).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.M., A.C., and D.L. performed experiments; S.M. analyzed data; S.M., P.W., and W.-L.Y. interpreted results of experiments; S.M. prepared figures; S.M. drafted manuscript; P.W. and W.-L.Y. conceived and designed research; P.W. and W.-L.Y. edited and revised manuscript; P.W. and W.-L.Y. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present address for S. Matsuo: Dept. of Surgery II, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, Tokyo, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham E. Neutrophils and acute lung injury. Crit Care Med Suppld 31: S195–S199, 2003. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057843.47705.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acosta S. Epidemiology of mesenteric vascular disease: clinical implications. Semin Vasc Surg 23: 4–8, 2010. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arumugam TV, Okun E, Tang SC, Thundyil J, Taylor SM, Woodruff TM. Toll-like receptors in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Shock 32: 4–16, 2009. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318193e333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begalli F, Bennett J, Capece D, Verzella D, D'Andrea D, Tornatore L, Franzoso G. Unlocking the NF-kappaB conundrum: embracing complexity to achieve specificity. Biomedicines 5: 2017. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines5030050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner C, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Kroemer G. Decoding cell death signals in liver inflammation. J Hepatol 59: 583–594, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cartwright T, Perkins ND, L Wilson C. NFKB1: a suppressor of inflammation, ageing and cancer. FEBS J 283: 1812–1822, 2016. doi: 10.1111/febs.13627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corcos O, Nuzzo A. Gastro-intestinal vascular emergencies. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 27: 709–725, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui T, Miksa M, Wu R, Komura H, Zhou M, Dong W, Wang Z, Higuchi S, Chaung W, Blau SA, Marini CP, Ravikumar TS, Wang P. Milk fat globule epidermal growth factor 8 attenuates acute lung injury in mice after intestinal ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181: 238–246, 2010. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-625OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finley D. Recognition and processing of ubiquitin-protein conjugates by the proteasome. Annu Rev Biochem 78: 477–513, 2009. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081507.101607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fishman JE, Sheth SU, Levy G, Alli V, Lu Q, Xu D, Qin Y, Qin X, Deitch EA. Intraluminal nonbacterial intestinal components control gut and lung injury after trauma hemorrhagic shock. Ann Surg 260: 1112–1120, 2014. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goru SK, Pandey A, Gaikwad AB. E3 ubiquitin ligases as novel targets for inflammatory diseases. Pharmacol Res 106: 1–9, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grootjans J, Lenaerts K, Derikx JP, Matthijsen RA, de Bruïne AP, van Bijnen AA, van Dam RM, Dejong CH, Buurman WA. Human intestinal ischemia-reperfusion-induced inflammation characterized: experiences from a new translational model. Am J Pathol 176: 2283–2291, 2010. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassoun HT, Kone BC, Mercer DW, Moody FG, Weisbrodt NW, Moore FA. Post-injury multiple organ failure: the role of the gut. Shock 15: 1–10, 2001. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200115010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Havasi A, Borkan SC. Apoptosis and acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 80: 29–40, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huber JM, Tagwerker A, Heininger D, Mayer G, Rosenkranz AR, Eller K. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib aggravates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F451–F460, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90576.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue S, Nakase H, Matsuura M, Mikami S, Ueno S, Uza N, Chiba T. The effect of proteasome inhibitor MG132 on experimental inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Immunol 156: 172–182, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itoh M, Takaoka M, Shibata A, Ohkita M, Matsumura Y. Preventive effect of lactacystin, a selective proteasome inhibitor, on ischemic acute renal failure in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 298: 501–507, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi Y. The role of chemokines in neutrophil biology. Front Biosci 13: 2400–2407, 2008. doi: 10.2741/2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komander D, Rape M. The ubiquitin code. Annu Rev Biochem 81: 203–229, 2012. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060310-170328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee WL, Downey GP. Neutrophil activation and acute lung injury. Curr Opin Crit Care 7: 1–7, 2001. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lenaerts K, Ceulemans LJ, Hundscheid IH, Grootjans J, Dejong CH, Olde Damink SW. New insights in intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury: implications for intestinal transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 18: 298–303, 2013. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32835ef1eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun SC. NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2: 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magnani M, Crinelli R, Bianchi M, Antonelli A. The ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic system and other potential targets for the modulation of nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB). Curr Drug Targets 1: 387–399, 2000. doi: 10.2174/1389450003349056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mallick IH, Yang W, Winslet MC, Seifalian AM. Ischemia-reperfusion injury of the intestine and protective strategies against injury. Dig Dis Sci 49: 1359–1377, 2004. doi: 10.1023/B:DDAS.0000042232.98927.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuda A, Yang WL, Jacob A, Aziz M, Matsuo S, Matsutani T, Uchida E, Wang P. FK866, a visfatin inhibitor, protects against acute lung injury after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion in mice via NF-κB pathway. Ann Surg 259: 1007–1017, 2014. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuo S, Sharma A, Wang P, Yang WL. PYR-41, a ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 inhibitor, attenuates lung injury in sepsis. Shock 49: 442–450, 2018. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 454: 428–435, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mura M, Andrade CF, Han B, Seth R, Zhang Y, Bai XH, Waddell TK, Hwang D, Keshavjee S, Liu M. Intestinal ischemia-reperfusion-induced acute lung injury and oncotic cell death in multiple organs. Shock 28: 227–238, 2007. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000278497.47041.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murao Y, Loomis W, Wolf P, Hoyt DB, Junger WG. Effect of dose of hypertonic saline on its potential to prevent lung tissue damage in a mouse model of hemorrhagic shock. Shock 20: 29–34, 2003. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000071060.78689.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nalepa G, Rolfe M, Harper JW. Drug discovery in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5: 596–613, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nrd2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Napetschnig J, Wu H. Molecular basis of NF-κB signaling. Annu Rev Biophys 42: 443–468, 2013. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oppenheim JJ, Yang D. Alarmins: chemotactic activators of immune responses. Curr Opin Immunol 17: 359–365, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orlichenko LS, Behari J, Yeh TH, Liu S, Stolz DB, Saluja AK, Singh VP. Transcriptional regulation of CXC-ELR chemokines KC and MIP-2 in mouse pancreatic acini. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 299: G867–G876, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00177.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Padrissa-Altés S, Zaouali MA, Boncompagni E, Bonaccorsi-Riani E, Carbonell T, Bardag-Gorce F, Oliva J, French SW, Bartrons R, Roselló-Catafau J. The use of a reversible proteasome inhibitor in a model of Reduced-Size Orthotopic Liver transplantation in rats. Exp Mol Pathol 93: 99–110, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park PO, Haglund U, Bulkley GB, Fält K. The sequence of development of intestinal tissue injury after strangulation ischemia and reperfusion. Surgery 107: 574–580, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parks DA, Granger DN. Contributions of ischemia and reperfusion to mucosal lesion formation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 250: G749–G753, 1986. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1986.250.6.G749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Safránek R, Ishibashi N, Oka Y, Ozasa H, Shirouzu K, Holecek M. Modulation of inflammatory response in sepsis by proteasome inhibition. Int J Exp Pathol 87: 369–372, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2006.00490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sauaia A, Moore FA, Moore EE. Postinjury inflammation and organ dysfunction. Crit Care Clin 33: 167–191, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmekel B, Karlsson SE, Linden M, Sundström C, Tegner H, Venge P. Myeloperoxidase in human lung lavage. I. A marker of local neutrophil activity. Inflammation 14: 447–454, 1990. doi: 10.1007/BF00914095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh SS, Kang PM. Mechanisms and inhibitors of apoptosis in cardiovascular diseases. Curr Pharm Des 17: 1783–1793, 2011. doi: 10.2174/138161211796390994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Souza DG, Vieira AT, Soares AC, Pinho V, Nicoli JR, Vieira LQ, Teixeira MM. The essential role of the intestinal microbiota in facilitating acute inflammatory responses. J Immunol 173: 4137–4146, 2004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.4137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tak PP, Firestein GS. NF-kappaB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest 107: 7–11, 2001. doi: 10.1172/JCI11830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian XF, Zhang XS, Li YH, Wang ZZ, Zhang F, Wang LM, Yao JH. Proteasome inhibition attenuates lung injury induced by intestinal ischemia reperfusion in rats. Life Sci 79: 2069–2076, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ungermannova D, Parker SJ, Nasveschuk CG, Chapnick DA, Phillips AJ, Kuchta RD, Liu X. Identification and mechanistic studies of a novel ubiquitin E1 inhibitor. J Biomol Screen 17: 421–434, 2012. doi: 10.1177/1087057111433843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu GW, Ali M, Wood TE, Wong D, Maclean N, Wang X, Gronda M, Skrtic M, Li X, Hurren R, Mao X, Venkatesan M, Beheshti Zavareh R, Ketela T, Reed JC, Rose D, Moffat J, Batey RA, Dhe-Paganon S, Schimmer AD. The ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 as a therapeutic target for the treatment of leukemia and multiple myeloma. Blood 115: 2251–2259, 2010. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-231191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamanaka K, Houben P, Bruns H, Schultze D, Hatano E, Schemmer P. A systematic review of pharmacological treatment options used to reduce ischemia reperfusion injury in rat liver transplantation. PLoS One 10: e0122214, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Y, Kitagaki J, Dai RM, Tsai YC, Lorick KL, Ludwig RL, Pierre SA, Jensen JP, Davydov IV, Oberoi P, Li CC, Kenten JH, Beutler JA, Vousden KH, Weissman AM. Inhibitors of ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), a new class of potential cancer therapeutics. Cancer Res 67: 9472–9481, 2007. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yasuhara H. Acute mesenteric ischemia: the challenge of gastroenterology. Surg Today 35: 185–195, 2005. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-2924-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshida T, Kumagai H, Kohsaka T, Ikegaya N. Relaxin protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F1169–F1176, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00654.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Q, Lenardo MJ, Baltimore D. 30 Years of NF-κB: a blossoming of relevance to human pathobiology. Cell 168: 37–57, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]