Abstract

Mainstay therapeutics are ineffective in some people with asthma, suggesting a need for additional agents. In the current study, we used vagal ganglia transcriptome profiling and connectivity mapping to identify compounds beneficial for alleviating airway hyperreactivity (AHR). As a comparison, we also used previously published transcriptome data from sensitized mouse lungs and human asthmatic endobronchial biopsies. All transcriptomes revealed agents beneficial for mitigating AHR; however, only the vagal ganglia transcriptome identified agents used clinically to treat asthma (flunisolide, isoetarine). We also tested one compound identified by vagal ganglia transcriptome profiling that had not previously been linked to asthma and found that it had bronchodilator effects in both mouse and pig airways. These data suggest that transcriptome profiling of the vagal ganglia might be a novel strategy to identify potential asthma therapeutics.

Keywords: airway hyperreactivity, asthma, neurons, therapeutics, transcriptome sequencing, vagus

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a chronic airway disease characterized by wheezing, chest tightness, cough, and variable airflow obstruction (31). Exaggerated airway narrowing in response to a variety of stimuli, termed airway hyperreactivity (AHR), is a hallmark feature of asthma (13). Our current understanding of AHR places inflammation at the center of its pathogenesis (34). However, therapeutics that directly target inflammation, such as glucocorticoids, are not effective in all people with asthma (65). Thus the identification and development of additional therapeutics that do not directly target inflammatory pathways might be of significant clinical value.

One attractive candidate is the nervous system and specifically, the vagus nerve. As early as the 17th century, anticholinergics, which prevent the postsynaptic actions of acetylcholine released from the vagus nerve, were explored as therapeutics for asthma (64). However, the contribution of the nervous system to AHR is complex and involves inflammation-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Specifically, Tränkner and colleagues (91) found that ablation of vagal sensory neurons expressing the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1, prevented AHR in ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitized mice without decreasing airway inflammation. In our previous work (66), we found that loss of acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) 1a, a proton-gated neuronal cation channel expressed in the vagal ganglia and other neural compartments, also prevented AHR without decreasing airway inflammation.

Yet others have found that the silencing of vagal sensory neurons that express Nav1.8 (88) or elimination of the transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily A, member 1, decreases both AHR and airway inflammation (10). Thus two contrasting roles for vagal sensory neurons have been described: those that modify AHR, independent of inflammation, and those that modify AHR and inflammation. This observation makes vagal ganglion neurons an appealing target for therapeutics.

Molecular profiling has enhanced therapeutic discovery for several diseases (17, 40, 81). In light of this and in light of our recent observation that mice with targeted disruptions to ASIC1a lack AHR despite robust inflammation (66), we hypothesized that vagal ganglia transcriptome profiling might provide unique insight into potential asthma therapeutics. To test this hypothesis, we probed the vagal ganglia of nonsensitized and OVA-sensitized wild-type (WT) and ASIC1a−/− mice. This enabled the comparison of transcripts from animals that lacked AHR but exhibited inflammation (OVA-sensitized ASIC1a−/− mice) with transcripts from animals that displayed both inflammation and AHR (OVA-sensitized WT mice) (66). We also used previously published transcriptome data of OVA-sensitized murine lung tissue (12) and endobronchial biopsies of human asthmatics (100) as a comparison and control.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Adult (8–9 wk old) male ASIC1a−/− (62) and WT mice were maintained on a congenic C57BL/6J background. Additional C57BL/6 WT mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and were used only for testing acute effects of alverine citrate and for making lung slices. Male piglets (2–3 days old) were euthanized by intracardiac Euthasol (Vibrac, Fort Worth, TX), as previously described (85). All procedures adhered to and were approved by the University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee.

OVA sensitization.

Mice were sensitized, as previously described (66, 72). Briefly, 8- to 9-wk-old male mice were sensitized by intraperitoneal injection of 10 μg OVA (MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, MO), mixed with 1 mg alum in 0.9% saline on days 0 and 7. Control mice received saline with 1 mg alum on days 0 and 7. Starting on day 14, a 1% OVA or 0.9% saline solution was nebulized for 40 min to the mice for 3 consecutive days. This equated to each mouse seeing three total challenges, with a single challenge occurring each day for 3 consecutive days (days 14–16).

For testing the effect of alverine citrate during the OVA-sensitization protocol, alverine citrate was provided as a multiple dose regimen. Specifically, alverine citrate or 0.5% DMSO vehicle was dissolved in the alum/OVA mixture at dose 15 mg/kg and delivered at days 0 and 7. On days 14–16, alverine citrate or 0.5% DMSO vehicle was delivered intraperitoneally in 0.9% saline, 30 min before nebulization with 1% OVA. On the day of flexiVent measurements (day 17), alverine citrate or 0.5% DMSO was delivered intraperitoneally in 0.9% saline, 30 min before testing by flexiVent.

Bronchoalveolar lavage and analyses.

Lungs received three sequential, 1-ml lavages of 0.9% sterile saline delivered into the airways through a cannula secured in the euthanized mouse trachea, as previously described (66). All collected material from one mouse was pooled and spun at 500 g, and the supernatant was removed and frozen at −80°C. Cells were counted on a hemocytometer, as previously described (66). IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 were assayed by DuoSet ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Vagal ganglia isolation.

Mice were euthanized by overdose of isoflurane inhalation following the OVA-sensitization protocol (on day 17 of protocol). Mice used for vagal ganglia collection did not undergo flexiVent procedures because of the potential confound that methacholine and mechanical stimulation of the airways (i.e., methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction) might impart on the vagal ganglia transcriptome. This approach is consistent with previous studies in which transcriptome sequencing has been performed in OVA-sensitized mouse lung tissues without analysis of airway resistance (12). Following euthanasia, the vagal ganglia were exposed by gently tracing the vagus nerve back to the base of the skull using protocols similar to those previously described (50, 66). The ganglia were delicately removed and immediately placed in TRIzol stored at −80°C until RNA isolation. The total ganglia, including any connective tissues of the ganglion capsule, inflammatory cells that may have migrated to the ganglion, satellite cells, blood cells, and blood vessels covering the ganglia, were not removed and were therefore included.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR.

RNA from the vagal ganglia was isolated using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue kit (a chloroform/phenol-based RNA extraction kit; Qiagen, Germantown, MD), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The optional DNase digestion was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using an RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen). RNA integrity was assessed with an Agilent bioanalyzer by the University of Iowa DNA Core. To confirm RNA sequencing results, RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript VILO Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the RNA and Master Mix were allowed to incubate for 10 min at 25°C, followed by 60 min at 42°C, followed by 5 min at 85°C. Primer and probes for murine peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (ppar)γc1A, cluster of differentiation (CD)93, chondrolectin (chodl), and actin were obtained from GeneCopoeia (Rockville, MD) and run on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturers’ protocol. pparγc1A, a gene identified by signature 1, was chosen because of the proposed bronchodilatory effect of PPARγ1 agonists (82). CD93, a gene that increased in response to OVA sensitization in ASIC1a−/− mice, compared with nonsensitized ASIC1a−/− mice, was chosen because it is reportedly involved in nervous system inflammation (47). Chodl, a gene that showed differential regulation in OVA-sensitized ASIC1a−/− and OVA-sensitized WT mice, was chosen because it affects neuronal outgrowth and survival (79).

RNA from total mouse lung was isolated using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue kit (according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The optional DNase digestion was also Qiagen), performed using a RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen), as detailed by the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA integrity was assessed by an Agilent nioanalyzer by the University of Iowa DNA Core. The lung RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript VILO Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the RNA and Master Mix were allowed to incubate for 10 min at 25°C, followed by 60 min at 42°C, followed by 5 min at 85°C. Quantitative PCR for mucin 5AC (muc5AC) was performed using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Qiagen) and run on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Primers were designed for murine muc5AC, as previously described (66, 72): muc5ac forward 5′-GTGGTGGAAACTGACATTGG-3′; muc5ac reverse 5′-CATCAAAGTTCCCACACAGG-3′. Primers for mouse actin were used as a housekeeping gene: actin forward 5′-CTGTGGCATCCATGAAACTACA-3′; actin reverse 5′-GTAATCTCCTTCTGCATCCTGTCA-3′.

flexiVent.

flexiVent procedures were performed as previously described (66, 72). Briefly, a tracheotomy was performed in anesthetized mice (ketamine-xylazine), and a cannula (blunted 18-gauge needle) was inserted into the tracheas. Mice were ventilated at 150 breaths/min at a volume of 10 ml/kg body mass and then administered a paralytic (rocuronium bromide). Increasing doses of methacholine were aerosolized using an ultrasonic nebulizer. The aerosols were delivered for 10 s into the inspiratory line of the ventilator. Measurements for each methacholine dose were taken at 10-s intervals over the course of 5 min. Airway resistance was measured using a single compartment model (i.e., dynamic resistance of the respiratory system). For drug studies, alverine citrate or vehicle was delivered at designated doses, 30 min before the start of flexiVent measurements.

Chemicals.

Alverine citrate (Selleckchem.com, Houston, TX) was dissolved in 0.5% DMSO/0.9% saline solution at a dose of 15 mg/ml. The pH of nebulized alverine citrate was titrated with NaOH to equal the pH of 0.9% saline (pH ~5.5). Substance P (MilliporeSigma) was dissolved in PBS, not containing calcium or magnesium ions (PBS−/−). Acetyl-β-methacholine-chloride (MilliporeSigma) was dissolved in 0.9% saline for flexiVent studies or PBS−/− for lung slice studies.

Histopathology.

Following mouse euthanasia, the left lung was removed and placed in 10% normal-buffered formalin. Samples were sectioned and stained as previously described (51, 66). A pathologist masked to groups performed scoring on hematoxylin-eosin-stained mouse lung sections (30). The following scores were assigned for bronchoperivascular inflammation severity: 1, within normal limits; 2, focal solitary cells with uncommon aggregates; 3, multifocal nominal- to moderate-sized aggregates; and 4, moderate to high cellularity, multifocal, large cellular aggregates that may be expansive into adjacent tissues. The following scores were assigned for perivascular inflammation distribution: 1, within normal limits; 2, minor to localized aggregates, <33% of lung; 3, multifocal aggregates, 33–66% of lung; 4, coalescing to widespread, >66% of lung.

RNA sequencing.

The vagal ganglia cDNA library construction and RNA sequencing were performed by the University of Iowa DNA Core. Briefly, 5 ng total RNA was used to prepare cDNA using the Ovation RNA-Seq System V2 (NuGen Technologies, San Carlos, CA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting cDNA was sheared using the Covaris E220-focused ultrasonicator (Covaris, Woburn, MA), such that the majority of the fragments were in the range of 150–500 bp. Sheared cDNA (500 ng) was taken into the KAPA Hyper Prep kit for Illumina sequencing (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA), and the indexed sequencing libraries generated were pooled in equimolar concentrations. The pooled libraries were sequenced on the HiSeq Sequencer 2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA) with a 100-bp paired-end sequencing by synthesis chemistry. The vagal ganglia of three individual mice for each condition were prepared separately and used.

Mapping and differential gene expression.

Fastq files were aligned to the mouse mm9 genome using tophat2 (v. 2.0.13). Aligned files were summarized to counts via the featureCount tool, part of the subread package (v. 1.4.6). Count files were imported into R, and differential expression was assessed using the DESeq2 package (v. 1.5.3). We considered all transcript changes with P ≤ 0.05 as significant.

Lung slices.

Mouse lungs were excised and filled with a 2% low-melt agarose/DMEM solution by cannulating the trachea with a 22-gauge needle. For porcine lung slices, the porpoise lobe was removed and inflated with 2% low-melt agarose, as previously described (18). Both murine and porcine lungs were sectioned on a sliding microtome at a thickness of 300 µm. Slices were cultured in 90% DMEM-10% FBS-1% penicillin-streptavidin for 2 days. They were imaged with an Olympus X81 inverted microscope. Time-lapse video was taken with images captured every 5 s.

CMAP Build 02.

Transcripts were converted to Affymetrix U133A identifiers when identifiers were available (signature 1: 11/15, 31/44; signature 2: 318/448, 83/136; signature 3: 90/139, 4/9; signature 4: 19/28, 12/18). The connectivity map (CMAP) was queried and compound lists obtained using the “detailed results” function. Compound classifications were assigned using DrugCentral (95), ChEMBL (56), and PubChem (75).

Literature mining.

The name of each compound and the word “asthma” were searched in PubMed. Titles of articles were used for initial screening; a clear relevance to asthma or AHR was needed to merit further screening. Key words for title screening included airway, allergic, sensitization, disease, bronchoconstriction, hyperreactivity, hyperresponsiveness, and asthma. Abstracts and articles that were selected based on title were read. Attention was paid to whether a compound provided benefit in asthma, AHR, or bronchoconstriction. In cases where there were greater than three studies, more than two studies needed to show a negative effect for a compound to be deemed as having a worsening effect. In cases where there were greater than three studies, more than two studies needed to show a beneficial effect for the compound to be deemed as having a beneficial effect.

DisGeNET.

The list of transcripts comprising signatures 1–3 was individually queried using the “gene” database. The diseases associated with each individual transcript were downloaded in Excel and compiled into a single worksheet.

Statistical analysis.

A two-way ANOVA was performed for studies with two or more groups and two or more treatments. When two or more groups were present, but only one condition was being tested, a one-way ANOVA was performed. Post hoc comparisons were performed using a Sidak’s multiple comparison test or least significant difference test. For RNA sequencing, only two treatments were compared at a time using DeSeq2 analysis in R. For histopathological scoring, a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was performed. Contingency tables and χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact test were used to examine the dependency of a compound being beneficial or negative on the signature being queried. For all other studies, a Student’s unpaired t-test was performed. All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0a. Significance for all tests was assessed as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Loss of ASIC1a and OVA sensitization influence the vagal ganglia transcriptome.

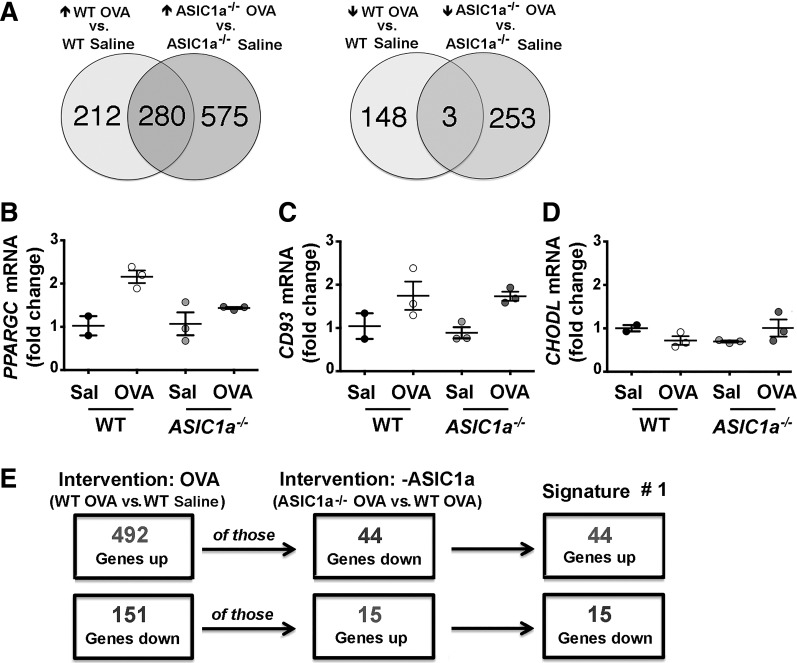

OVA sensitization is a common model that induces AHR in laboratory animals (58). Therefore, we first evaluated the vagal ganglia transcriptional response to OVA sensitization. We found that OVA sensitization increased 492 transcripts and decreased 151 transcripts in the vagal ganglia of WT mice compared with nonsensitized WT mice (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Table S1). By contrast, in ASIC1a−/− mice, OVA sensitization increased 855 transcripts and decreased 256 transcripts compared with nonsensitized ASIC1a−/− mice (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Table S1). Because previous studies have shown that the disruption of the ASIC1a gene or inhibition of ASIC currents changes neural activity (102, 103), we also examined the effect of loss of ASIC1a on the vagal ganglion transcriptome in nonsensitized mice. We found that loss of ASIC1a increased 159 transcripts and decreased 269 transcripts in the vagal ganglia compared with WT mice (Supplemental Table S2). The use of primer and probe sets for a few select transcripts, with our limited RNA remaining, revealed transcript changes consistent with those found by RNA sequencing (Fig. 1, B–D). Thus OVA sensitization impacted the vagal ganglia transcriptomes in both WT and ASIC1a−/− mice. Moreover, the presence or absence of ASIC1a influenced the vagal ganglia transcriptional response to OVA sensitization.

Fig. 1.

Ovalbumin (OVA)-responsive transcripts in the vagal ganglia of wild-type (WT) and acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC)1a−/− mice. A: Venn diagram showing numbers of transcripts that were increased or decreased by OVA sensitization in WT (left) or ASIC1a−/− (right) mice. Data are from RNA sequencing of the vagal ganglia of 3 individual mice for each condition. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to validate transcript changes identified by RNA sequencing for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPARGC; B), cluster of differentiation (CD)93 (C), and chondrolectin (CHODL; D). Data are expressed as means ± SE and are relative to their respective nonsensitized control. Individual points are data collected from a single mouse. E: flow chart depicting the strategy to obtain signature 1. Sal, saline (nonsensitized).

A portion of OVA-responsive vagal ganglion transcripts are normalized by loss of ASIC1a and offer potential therapeutic value.

We next implemented a nonconventional analysis akin to identifying transcripts that were increased or decreased in a disease state (i.e., OVA sensitization) but reversed following an intervention that elicited benefit (i.e., loss of ASIC1a). That is, we asked whether any of the 492 transcripts elevated by OVA sensitization in WT mice were decreased or “normalized” by loss of ASIC1a; we identified 44 transcripts (Fig. 1E and Supplemental Table S1). We also asked whether any of the 151 transcripts repressed by OVA sensitization in WT mice were increased or normalized by loss of ASIC1a; we identified 15 transcripts (Fig. 1E and Supplemental Table S1). We termed this list of 59 (i.e., 44 + 15) transcripts signature 1.

We predicted that some transcripts comprising signature 1 might be of therapeutic significance. For example, if a transcript played a causal role in the manifestation of AHR, then its expression might appear normalized by loss of ASIC1a (i.e., ASIC1a−/− mice lack AHR) (66). Alternatively, if a transcript’s expression was induced or suppressed as part of a compensatory and/or adaptive response to AHR, then its expression might also appear normalized by loss of ASIC1a, since ASIC1a−/− mice lack AHR (66). In the latter case, such transcripts might be beneficial and/or have protective effects (38, 78, 84). We also conceived that signature 1 transcripts might have no bearing or role in AHR.

To explore these possibilities, we performed connectivity mapping. The CMAP is a database of gene signatures derived from 6,100 compounds applied to human cell lines (41). It provides information regarding the connectedness of genes, drugs, and disease states through identification of common gene-expression signatures (86). If signature 1 transcripts participated in the manifestation of AHR, then compounds with gene signatures that mimicked signature 1 might induce AHR or worsen asthma symptoms (Fig. 2). The converse might also be true, in which compounds with gene signatures that reversed signature 1 might be beneficial and mitigate AHR or alleviate asthma symptoms. On the other hand, if transcripts represented protective, beneficial adaptations secondary to AHR, then compounds with gene signatures that mimicked signature 1 might be beneficial. If true, then compounds with gene signatures that reversed signature 1 might also be beneficial or at least not be of negative consequences. For example, imagine a gene with a baseline expression of one. In response to inflammation, it increases its expression to 10 as means to compensate and/or protect against inflammation. If reversed back to one, a negative consequence would not be expected, as that was the resting (baseline) expression. Therefore, if transcripts comprising signature 1 were beneficial due to compensatory changes, then compounds that reversed signature 1 would not be of anticipated negative consequence, since reversal would effectively be returning to a resting state. As a comparison, we also probed CMAP with transcriptome data of OVA-sensitized murine lung tissue (12) (signature 2; Fig. 3 and Supplemental Table S3) and endobronchial biopsies of human asthmatics (100) (signature 3; Fig. 4 and Supplemental Table S3).

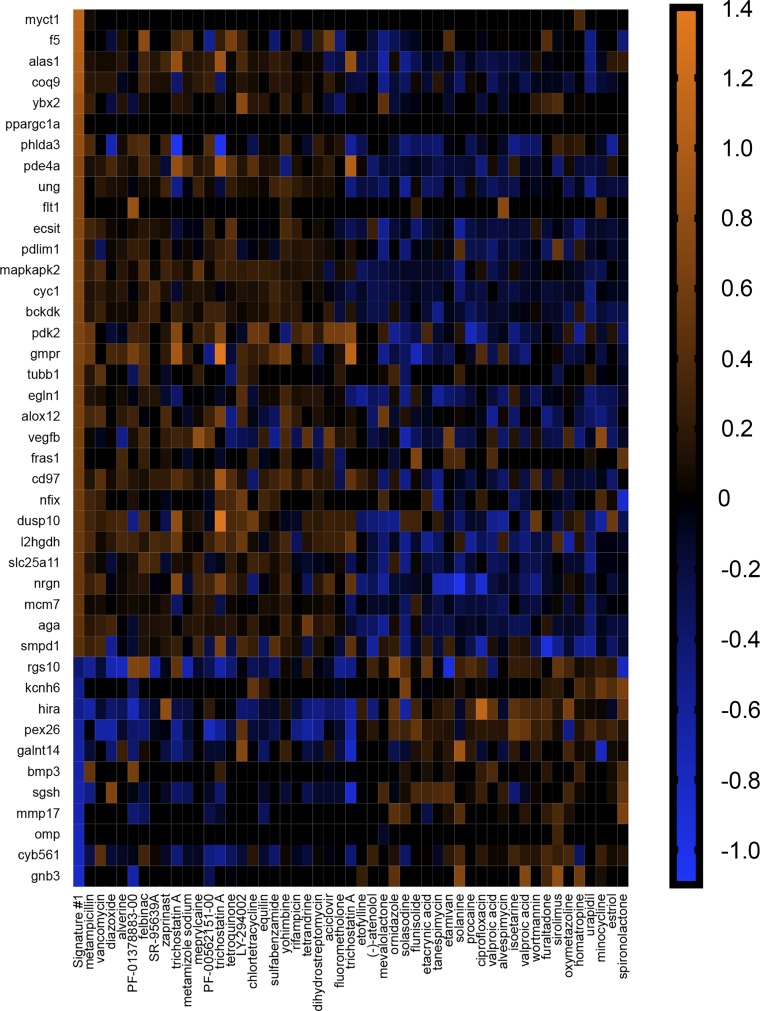

Fig. 2.

Signature 1 identifies agents useful for treating airway hyperreactivity. Heatmap illustrating the log2 fold changes of transcripts comprising signature 1 and associated compounds inducing the same (left-most 25 compounds) or opposite (right-most 25 compounds) gene signatures. Compounds were obtained through query of the connectivity map (CMAP). Genes (11/15 and 31/44) had Affymetrix identifiers that could be used in CMAP. Original scale is in log2 fold change.

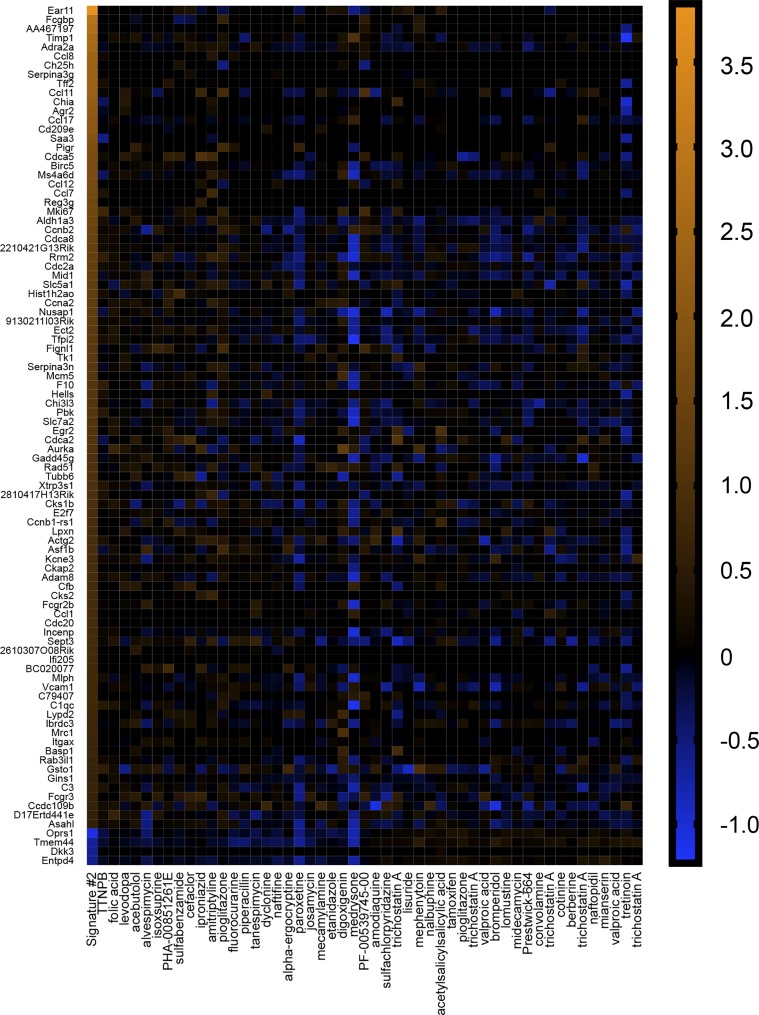

Fig. 3.

Signature 2 identifies agents useful for treating airway hyperreactivity. Heatmap illustrating the log2 fold changes of transcripts comprising signature 2 and associated compounds inducing the same (left-most 25 compounds) or opposite (right-most 25 compounds) gene signatures. Compounds were obtained through query of the connectivity map (CMAP). Genes (90/139 and 4/9) had Affymetrix identifiers that could be used in CMAP. Original scale is in log2 fold change.

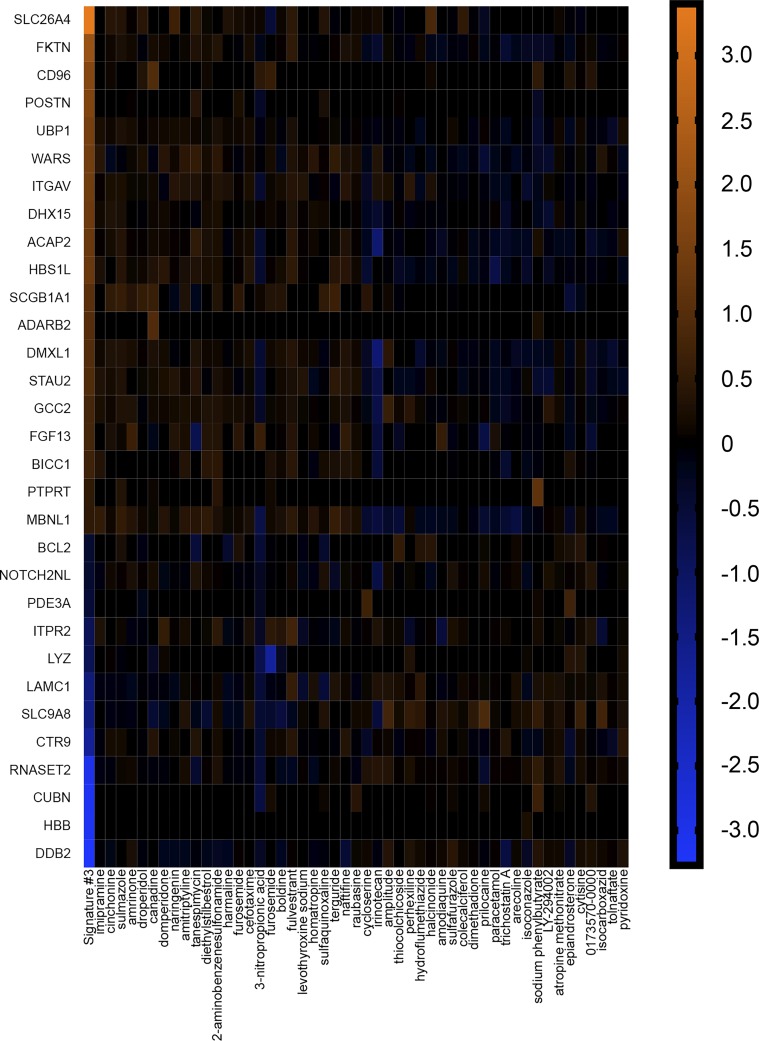

Fig. 4.

Signature 3 identifies agents useful for treating airway hyperreactivity. Heatmap illustrating the log2 fold changes of transcripts comprising signature 3 and associated compounds inducing the same (left-most 25 compounds) or opposite (right-most 25 compounds) gene signatures. Compounds were obtained through query of the connectivity map (CMAP). Genes (19/28 and 12/18) had Affymetrix identifiers that could be used in CMAP. Original scale is in log2 fold change.

We first looked at compounds that mimicked each signature. We found that three of the top 25 (vancomycin, metamizole sodium, and rifampicin) that mimicked signature 1 (Fig. 2) worsened asthma symptoms in people (14, 21, 39) (Table 1), whereas seven were beneficial and decreased airway obstruction (57), smooth muscle contraction (6, 99), and AHR (3, 22) (Table 1). For signature 2 (Fig. 3), two compounds were of negative consequence and increased risk (7) or induced (52) asthma, whereas four were beneficial and decreased bronchoconstriction (2, 5, 28) or AHR (55) (Table 2). Similar results were observed with signature 3 (Fig. 4), in which two compounds were of negative consequence and increased risk (97) or induced (9) asthma, and eight were of benefit and decreased bronchoconstriction (2, 44, 48, 60, 73) or AHR (37, 76) (Table 3). One compound that mimicked signature 2—isoxsuprine—had a single report, suggesting that it decreased bronchoconstriction in asthma (93), and an additional single report, suggesting its use was a risk factor for the development of asthma (11). A 3 × 2 contingency table analysis and a two-tailed χ2 test revealed that the chance of identification of a compound that was of beneficial consequence in asthma/AHR was not different among signatures [χ2 (2, n = 75) = 1.83, P = 0.41].

Table 1.

CMAP compounds that mimicked signature 1

| Rank | Drug | Condition (Reference) | Classification/Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Metampicillin | Antibiotic | |

| 2 | Vancomycin | Asthma* (14) | Antibiotic |

| 3 | Diazoxide | Vasodilator | |

| 4 | Alverine | Spasmolytic | |

| 5 | PF-01378883-00 | Unknown | |

| 6 | Felbinac | Anti-inflammatory | |

| 7 | SR-95639A | Unknown | |

| 8 | Zaprinast | Bronchoconstriction (6) | Phosphodiesterase inhibitor |

| 9 | Trichostatin A | Hyperresponsiveness (3) | Histone deacetylase inhibitor |

| 10 | Metamizole sodium | Asthma* (39) | Analgesic |

| 11 | Meprylcaine | Local anesthetic | |

| 12 | PF-00562151-00 | Unknown | |

| 13 | Trichostatin A | Hyperresponsiveness (3) | Histone deacetylase inhibitor |

| 14 | Tetroquinone | Chemical compound | |

| 15 | LY-294002 | Hyperresponsiveness (22) | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor |

| 16 | Chlortetracycline | Antibiotic | |

| 17 | Equilin | Conjugated estrogen | |

| 18 | Sulfabenzamide | Anti-infective | |

| 19 | Yohimbine | Alkaloid | |

| 20 | Rifampicin | Asthma* (21) | Antibiotic |

| 21 | Tetrandrine | Asthma (99) | Calcium channel blocker |

| 22 | Dihydrostreptomycin | Antibiotic | |

| 23 | Acyclovir | Asthma (57) | Antiviral |

| 24 | Fluorometholone | Corticosteroid | |

| 25 | Trichostatin A | Hyperresponsiveness (3) | Histone deacetylase inhibitor |

Rank is order of correlation. CMAP, connectivity map.

Adverse effect.

Table 2.

CMAP compounds that mimicked signature 2

| Rank | Drug | Condition (Reference) | Classification/Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arotinoid acid | Arotinoid | |

| 2 | Folic acid | Asthma* (7) | Vitamin |

| 3 | Levodopa | Dopamine agonist | |

| 4 | Acebutolol | Beta adrenergic receptor blocker | |

| 5 | Alvespimycin | HSP90 inhibitor | |

| 6 | Isoxsuprine | Asthma (mixed) (11, 93) | Beta adrenergic receptor agonist |

| 7 | PHA-00851261E | Unknown | |

| 8 | Sulfabenzamide | Antibiotic | |

| 9 | Cefaclor | Antibiotic | |

| 10 | Iproniazid | Bronchoconstriction (5) | Antidepressant |

| 11 | Amitriptyline | Bronchoconstriction (2) | Antidepressant |

| 12 | Pioglitazone | Asthma (55) | PPAR agonist |

| 13 | Fluorocurarine | Sympathetic ganglion blocker | |

| 14 | Piperacillin | Bronchoconstriction* (52) | Antibiotic |

| 15 | Tanespimycin | HSP90 inhibitor | |

| 16 | Dyclonine | Local anesthetic | |

| 17 | Naftifine | Antifungal | |

| 18 | Alpha ergocryptine | Alkaloid | |

| 19 | Paroxetine | Antidepressant | |

| 20 | Josamycin | Antibiotic | |

| 21 | Mecamylamine | Bronchoconstriction (28) | Cholinergic antagonist |

| 22 | Etanidazole | Decreases glutathione | |

| 23 | Digoxigenin | Steroid | |

| 24 | Medrysone | Corticosteroid | |

| 25 | PF-00539745-00 | Unknown |

Rank is order of correlation. CMAP, connectivity map; HSP, heat shock protein; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor.

Adverse effect.

Table 3.

CMAP compounds that mimicked signature 3

| Rank | Drug | Condition (Reference) | Classification/Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Imipramine | Antidepressant | |

| 2 | Cinchonine | Alkaloid | |

| 3 | Sulmazole | Bronchoconstriction (60) | Adenosine receptor antagonist |

| 4 | Amrinone | Bronchoconstriction (44) | Phosphodiesterase inhibitor |

| 5 | Droperidol | Bronchoconstriction (73) | Dopamine antagonist |

| 6 | Canadine | Alkaloid | |

| 7 | Domperidone | Asthma (37) | Dopamine antagonist |

| 8 | Naringenin | Asthma (76) | Flavinoid |

| 9 | Amitriptyline | Bronchoconstriction (2) | Antidepressant |

| 10 | Tanespimycin | HSP90 inhibitor | |

| 11 | Diethylstilbestrol | Asthma* (97) | Nonsteroidal estrogen |

| 12 | 2-Aminobenzenesulfonamide | Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor | |

| 13 | Harmaline | Alkaloid | |

| 14 | Furosemide | Asthma (48) | Diuretic |

| 15 | Cefotaxime | Antibiotic | |

| 16 | 3-Nitropropionic acid | Mycotoxin | |

| 17 | Furosemide | Asthma (48) | Diuretic |

| 18 | Boldine | Alkaloid | |

| 19 | Fulvestrant | Chemotherapy | |

| 20 | Levothyroxine sodium | Asthma* (9) | Synthetic thyroxine |

| 21 | Homatropine | Anticholinergic | |

| 22 | Sulfaquinoxaline | Antiprotazoal | |

| 23 | Terguride | Serotonin antagonist and dopamine agonist | |

| 24 | Naftifine | Antifungal | |

| 25 | Raubasine | Antihypertensive |

Rank is order of correlation. CMAP, connectivity map; HSP, heat shock protein.

Adverse effect.

We also examined the top 25 compounds that reversed each signature. For signature 1, we found that ~50% were beneficial in experimental or clinical airway disease (Table 4) (19, 26, 35, 53, 54, 63, 68, 80, 83, 94). Notably, two compounds—isoetarine and flunisolide—were identified as stand-alone or combination therapies for asthma (20, 45). None of the compounds that reversed signature 1 were found to worsen or induce asthma. Of the compounds that reversed signature 2, 13 were beneficial and decreased bronchoconstriction (15, 43, 71) or AHR (3, 43, 49, 55, 67, 68) (Table 5), and one induced asthma (87). For signature 3, eight were beneficial and mitigated bronchoconstriction (29, 32) or AHR (3, 22, 26) and decreased asthma symptoms (16, 74) or incidence of asthma (46) (Table 6). An additional two increased the risk of (27) or induced (89) asthma. None of the compounds that reversed signature 2 or 3 had evidence for clinical use. A 3 × 2 contingency table analysis and a two-tailed χ2 test revealed that the chance of identification of a compound that was of potential benefit in asthma/AHR was not different among signatures [χ2 (2, n = 75) = 2.69, P = 0.26]. The performance of a Fisher’s exact test on the number of combined clinical agents identified 0by the vagal ganglia (two of 50) and the number of combined clinical agents identified by the airway samples (zero of 100) revealed a trend in the vagal ganglia to identify a greater number of clinical agents (P = 0.10). Thus three important observations arose from these studies: 1) the vagal ganglion transcriptome was as effective as the airway tissue in identification of potential therapeutics; 2) clinical agents were only identified by the vagal ganglia transcriptome; and 3) compounds that mimicked or reversed a signature were both of potential significance in therapeutic discovery (Tables 7 and 8).

Table 4.

CMAP Compounds that reversed signature 1

| Rank | Drug | Condition (Reference) | Classification/Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6076 | Etofylline | Asthma (94) | Bronchodilator |

| 6077 | (−)-Atenolol | Beta adrenergic receptor antagonist | |

| 6078 | Mevalolactone | Chemical compound | |

| 6079 | Ornidazole | Antiprotozoal | |

| 6080 | Solasodine | Alkaloid | |

| 6081 | Flunisolide | Asthma* (20) | Glucocorticoid |

| 6082 | Etacrynic acid | Bronchoconstriction (63) | Diuretic |

| 6083 | Tanespimycin | HSP90 inhibitor | |

| 6084 | Etamivan | Asthma (83) | Respiratory stimulant |

| 6085 | Solanine | Alkaloid | |

| 6086 | Procaine | Asthma (80) | Local anesthetic |

| 6087 | Ciprofloxacin | Antibiotic | |

| 6088 | Valproic acid | Hyperresponsiveness (68) | Anticonvulsant |

| 6089 | Alvespimycin | HSP90 inhibitor | |

| 6090 | Isoetarine | Asthma* (45) | Bronchodilator |

| 6091 | Valproic acid | Hyperresponsiveness (68) | Anticonvulsant |

| 6092 | Wortmannin | Hyperresponsiveness (26) | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor |

| 6093 | Furaltadone | Antibiotic | |

| 6094 | Sirolimus | Asthma (54) | Immunosuppressant |

| 6095 | Oxymetazoline | Asthma (35) | Decongestant |

| 6096 | Homatropine | Anticholinergic | |

| 6097 | Urapidil | Bronchospasm (53) | Antihypertensive |

| 6098 | Minocycline | Asthma (19) | Antibiotic |

| 6099 | Estriol | Estradiol metabolite | |

| 6100 | Spironolactone | Diuretic |

Rank is order of correlation. CMAP, connectivity map; HSP, heat shock protein.

Approved for clinical treatment of asthma.

Table 5.

CMAP compounds that reversed signature 2

| Rank | Drug | Condition (Reference) | Classification/Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6076 | Amodiaquine | Bronchoconstriction (15) | Antimalarial |

| 6077 | Sulfachlorpyridazine | Sulfonamide | |

| 6078 | Trichostatin A | Hyperresponsiveness (3) | Histone deacetylase inhibitor |

| 6079 | Lisuride | Anti-Parkinson reagent | |

| 6080 | Mephenytoin | Anticonvulsant | |

| 6081 | Nalbuphine | Opioid antagonist | |

| 6082 | Acetylsalicylsalicylic acid | Asthma* (87) | Aspirin impurity |

| 6083 | Tamoxifen | Asthma (67) | Estrogen receptor blocker |

| 6084 | Pioglitazone | Asthma (55) | PPAR agonist |

| 6085 | Trichostatin A | Hyperresponsiveness (3) | Histone deacetylase inhibitor |

| 6086 | Valproic acid | Hyperresponsiveness (68) | Anticonvulsant |

| 6087 | Bromperidol | Neuroleptic | |

| 6088 | Lomustine | Chemotherapy | |

| 6089 | Midecamycin | Antibiotic | |

| 6090 | Prestwick-664 | Unknown | |

| 6091 | Convolamine | Sensory nerve blocker | |

| 6092 | Trichostatin A | Hyperresponsiveness (3) | Histone deacetylase inhibitor |

| 6093 | Cotinine | Alkaloid | |

| 6094 | Berberine | Bronchoconstriction (71) | Alkaloid |

| 6095 | Trichostatin A | Hyperresponsiveness (3) | Histone deacetylase inhibitor |

| 6096 | Naftopidil | Alpha adrenergic blocker | |

| 6097 | Mianserin | Bronchoconstriction (43) | Antidepressant |

| 6098 | Valproic acid | Hyperresponsiveness (68) | Anticonvulsant |

| 6099 | Tretinoin | Hyperresponsiveness (49) | All-trans retinoic acid |

| 6100 | Trichostatin A | Hyperresponsiveness (3) | Histone deacetylase inhibitor |

Rank is order of correlation. CMAP, connectivity map; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor.

Adverse effect.

Table 6.

CMAP compounds that reversed signature 3

| Rank | Drug | Condition (Reference) | Classification/Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6076 | Cycloserine | Antibiotic | |

| 6077 | Irinotecan | Chemotherapy | |

| 6078 | Wortmannin | Hyperresponsiveness (26) | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor |

| 6079 | Thiocolchicoside | Muscle relaxant | |

| 6080 | Perhexiline | Bronchoconstriction (29) | Antianginal |

| 6081 | Hydroflumethiazide | Diuretic | |

| 6082 | Halcinonide | Corticosteroid | |

| 6083 | Amodiaquine | Antimalarial | |

| 6084 | Sulfafurazole | Asthma (74) | Sulfonamide |

| 6085 | Colecalciferol | Asthma (46) | Vitamin D |

| 6086 | Dimethadione | Anticonvulsant | |

| 6087 | Prilocaine | Local anesthetic | |

| 6088 | Paracetamol | Asthma* (27) | Acetaminophen |

| 6089 | Trichostatin A | Hyperresponsiveness (3) | Histone deacetylase inhibitor |

| 6090 | Arecoline | Bronchoconstriction* (89) | Alkaloid |

| 6091 | Isoconazole | Antifungal | |

| 6092 | Sodium phenylbutyrate | Aromatic fatty acid | |

| 6093 | LY-294002 | Hyperresponsiveness (22) | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor |

| 6094 | Atropine methonitrate | Bronchoconstriction (32) | Anticholinergic; bronchodilator |

| 6095 | Epiandrosterone | Steroid hormone | |

| 6096 | Cytisine | Alkaloid | |

| 6097 | 0173570-0000 | Unknown | |

| 6098 | Isocarboxazid | Antidepressant | |

| 6099 | Tolnaftate | Antifungal | |

| 6100 | Pyridoxine | Asthma (16) | Vitamin B |

Rank is order of correlation. CMAP, connectivity map.

Adverse effect.

Table 7.

Summary of compounds examined in signatures 1–3

| Signature 1 | Signature 2 | Signature 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mimic | |||

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| “Beneficial” | 7 | 4 | 8 |

| “Worsen” | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Mixed | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Effect unknown | 15 | 18 | 15 |

| Clinical | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reverse | |||

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| “Beneficial” | 13 | 13 | 8 |

| “Worsen” | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Mixed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Effect unknown | 12 | 11 | 15 |

| Clinical | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Summary | |||

| n | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| “Beneficial” | 20 | 17 | 16 |

| “Worsen” | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Mixed | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Effect unknown | 27 | 29 | 30 |

| Clinical | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Table 8.

Common classifications of beneficial drugs

| Categorization | Drug Name | Signature |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphodiesterase inhibitor | Zaprinast | 1 |

| Amrinone | 2 | |

| Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor | LY-294002 | 1, 3 |

| Wortmannin | 1, 3 | |

| Bronchodilator | Etofylline | 1 |

| Isoetarine | 1 | |

| Atropine methonitrate | 3 | |

| Diuretic | Etacrynic acid | 1 |

| Furosemide | 3 | |

| Anticonvulsant | Valproic acid | 1, 2 |

| Histone deacetylase inhibitor | Trichostatin A | 1, 2, 3 |

| Antidepressant | Iproniazid | 2 |

| Amitriptyline | 2 | |

| Paroxetine | 2 | |

| Mianserin | 2 | |

| Amitriptyline | 3 | |

| Vitamin or vitamin derivative | Tretinoin | 2 |

| Colecalciferol | 3 | |

| Pyridoxine | 3 | |

| Anticholinergic | Mecamylamine | 2 |

| Atropine methonitrate | 3 |

Some differentially expressed transcripts in both the vagal ganglia and airway are asthma-associated genes.

The finding that signatures 1–3 identified potential or known therapeutic compounds suggested that each signature might contain transcripts of known significance to asthma. To examine this possibility, we queried DisGeNET, a catalog of genes and variants associated with human disease (59). We also assessed each transcript for associations with nervous system disorders for a comparison.

There were many transcripts not found in the DisGeNET database (Supplemental Tables S4–S6; shown as continuous “///”). For transcripts that were found in the DisGeNET database, ~5.5% (signature 1), 12.2% (signature 2), and 8.9% (signature 3) were categorized as being a biomarker, gene of altered expression, or genetic variant of asthma (Supplemental Tables S4–S9; blue rows). Signature 1 had the greatest percentage (70.7%) of transcripts associated with nervous system disorders (Supplemental Tables S4 and S7; gray-shaded rows). By comparison, 44.3% of transcripts comprising signature 2 (Supplemental Tables S5 and S8; gray-shaded rows) and 62.9% of transcripts comprising signature 3 were associated with nervous system disorders (as a biomarker, gene of altered expression, or genetic variant; Supplemental Tables S6 and S9; gray-shaded rows). Therefore, DisGeNET revealed that all signatures contained asthma-associated genes, with signature 1 containing the fewest asthma-associated genes and the greatest number of those related to the nervous system.

The vagal ganglia transcriptome reveals a compound that behaves like a bronchodilator.

One of the goals of this study was to identify potential asthma therapeutics through vagal ganglia transcriptome profiling. We thought this might be especially important, given that some mainstay therapeutics that directly target inflammation, such as glucocorticoids, are not effective in all people with asthma (65). The transcriptome analysis and connectivity mapping proved useful in this regard; however, we wondered whether any of the compounds identified by signature 1, which had not previously been linked to AHR or asthma and not classified as anti-inflammatories, might also have potential benefit.

To examine this possibility, we assessed all 50 signature 1 compounds and identified 25 that were of potential interest (i.e., those that had not been linked to asthma and were not anti-inflammatories). We then eliminated those that were of unknown classification or not of obvious neural significance (i.e., antibiotics, antiprotozoals, diuretics, estrogen, heat shock protein 90 inhibitor). This left eight candidates (diazoxide, alverine, meprylcaine, yohimbine, atenolol, solasodine, solanine, and homatropine). Of those, only homatropine and alverine citrate were of continued interest, due to their ability to modulate vagal nerve activity (1, 4, 8, 23). Because anticholinergics are currently used in asthma (61), we did not further explore homatropine. Thus we selected alverine citrate, a spasmolytic with a proposed mechanism of action different from traditional smooth muscle relaxants (90), for further investigation.

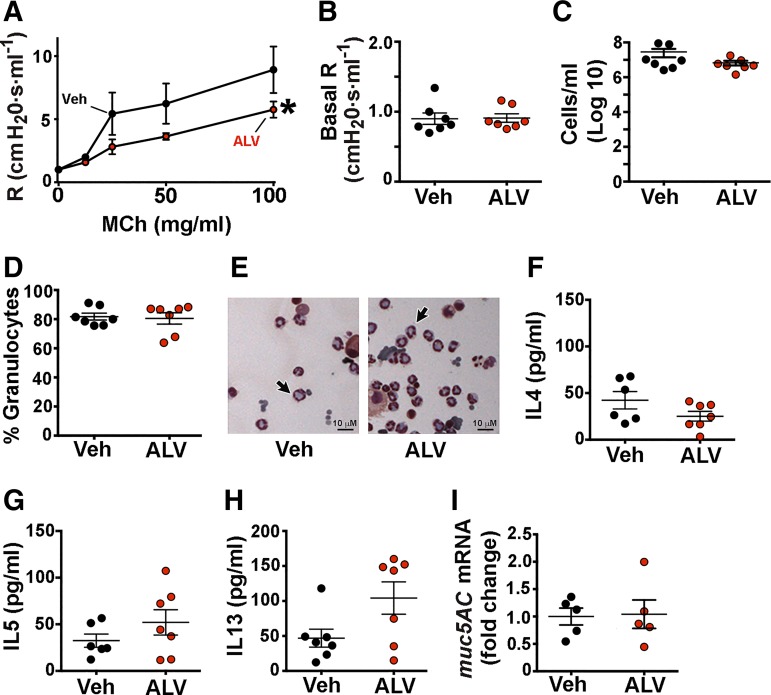

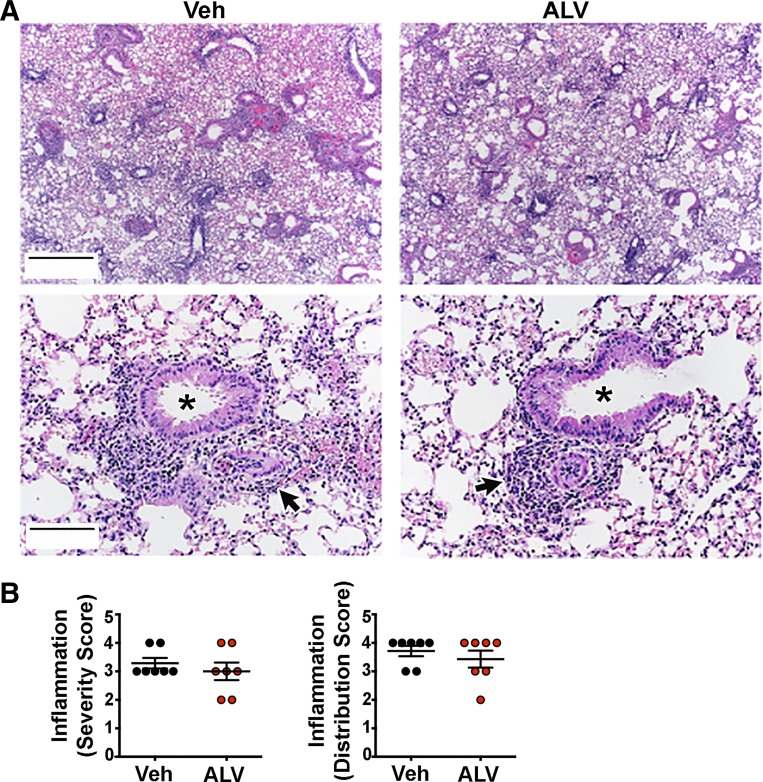

We treated OVA-sensitized WT mice with alverine citrate using a multiple dosing regimen and found decreased airway resistance in response to methacholine compared with vehicle-treated, OVA-sensitized mice (Fig. 5A). This decrease was not likely due to an effect of alverine citrate on baseline airway caliber, as alverine citrate- and vehicle-treated mice had similar basal airway resistance (Fig. 5B). We also did not find differences in the number of cells recovered from or the percentage of granulocytes observed in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid retrieved from alverine citrate-treated and vehicle mice (Fig. 5, C–E). Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid concentrations of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 were also not different between mice that received alverine citrate and vehicle (Fig. 5, F–H). Although IL-13 levels tended to be higher in alverine citrate-treated mice, this elevation did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.094). Since mucus obstruction can increase airway resistance (24), we also examined transcript abundance of muc5AC, the major mucus glycoprotein of allergic murine airways (25). We found no effect of alverine citrate (Fig. 5I), suggesting that a reduction in mucin expression was not a likely factor mediating alverine citrate’s beneficial effect. The severity and distribution of bronchoperivascular inflammation also did not differ between treatment groups (Fig. 6). We did not test alverine citrate in OVA-sensitized ASIC1a−/− mice because OVA-sensitized ASIC1a−/− mice lack AHR.

Fig. 5.

Alverine citrate decreases airway resistance. A: airway resistance in wild-type (WT) mice sensitized to ovalbumin (OVA) and treated intraperitoneally with either 15 mg/kg alverine citrate (ALV) or vehicle control (Veh) during the sensitization protocol and then 30 min before the methacholine (MCh) challenge. Resistance (R) was measured after increasing doses of methacholine. Data are means ± SE. For both conditions, n = 7 mice. *P < 0.05 by 2-way ANOVA. B: baseline airway resistance measured before administration of methacholine. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was assayed for total number of cells (C) and percentage of granulocyte cells (D). E: representative hematoxylin and eosin stain of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from OVA-sensitized WT mice treated with alverine citrate or vehicle control. Arrows indicate examples of granulocytes. Bronchoalveolar lavage concentrations of IL-4 (F), IL-5 (G), and IL-13 (H). I: quantitative RT-PCR of mucin 5AC (muc5AC) mRNA in airways. Individual data points represent data collected from an individual mouse. Bars and whiskers indicate means ± SE.

Fig. 6.

Alverine citrate (ALV) does not decrease bronchoperivascular inflammation in ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitized mice. A: representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of mouse lung sections. Asterisks indicate airways; arrows indicate examples of perivascular inflammation. Original scale bars, 700 μm (top); 140 μm (bottom). B: perivascular inflammation score. Individual data points represent data collected from an individual mouse. Data were examined for statistical significance using a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Veh, vehicle control.

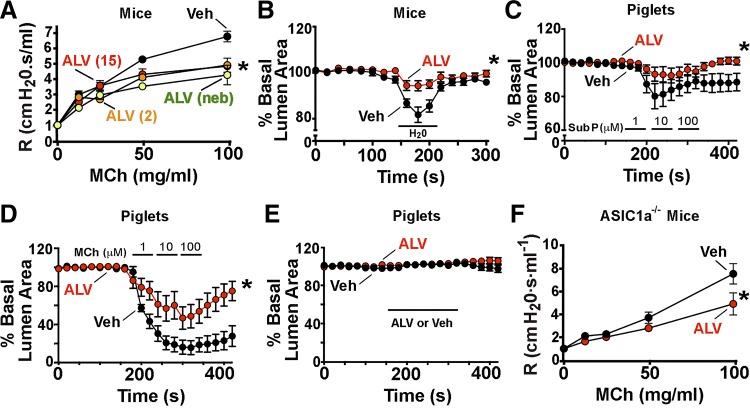

The ascertainment that alverine citrate reduced AHR without affecting inflammation suggested that it might act as a bronchodilator. We confirmed bronchodilator activity in nonsensitized WT mice and found that either acute intraperitoneal or nebulized delivery of alverine citrate decreased airway resistance (Fig. 7A). Similar effects were observed when alverine citrate was tested in porcine and murine lung slices. In murine lung slices, alverine citrate blunted water-mediated bronchoconstriction (Fig. 7B). In porcine lung slices, alverine citrate acutely reduced substance P- and methacholine-mediated airway contraction. Alverine citrate did not relax porcine airways in the absence of a procontractile stimulus (Fig. 7, C–E). We also tested whether the actions of alverine citrate were independent of ASIC1a. To do this, we delivered intraperitoneal alverine citrate acutely to nonsensitized ASIC1a−/− mice and found it reduced airway resistance (Fig. 7F). Thus the bronchodilator effect of alverine citrate did not require ASIC1a. Moreover, these findings suggested that other compounds identified by signature 1 might also have potential therapeutic value.

Fig. 7.

Alverine citrate decreases airway contraction to multiple stimuli and in 2 species. A: alverine (ALV; 15 or 2 mg/kg) or vehicle control (Veh) was administered intraperitoneally, 30 min before airway-resistance (R) measurements. Alverine citrate was also nebulized (neb; 15 mg/ml). Data are means ± SE; Veh, n = 4 mice; ALV (15 mg/kg ip), n = 4 mice; ALV (2 mg/kg ip), n = 3 mice; nebulized ALV, n = 3 mice. B: murine lung slices were incubated with 20 μM alverine citrate or vehicle control and stimulated to contract by perfusion with distilled water for 1 min (marked line, H2O). Data are means ± SE of lumen area as a percent of basal area. Veh, n = 9; ALV, n = 8. C: porcine lung slices were incubated with 20 μM alverine citrate or vehicle control and then stimulated to contract by perfusion with increasing concentrations of substance P (Sub P; 1, 10, and 100 μM). Veh, n = 5; ALV, n = 5. D: porcine lung slices were incubated with 20 μM alverine citrate or vehicle control and then stimulated to contract by perfusion with increasing concentrations of methacholine (MCh; 1, 10, and 100 μM). Veh, n = 4; ALV, n = 5. E: porcine lung slices were perfused with 20 μM alverine citrate or vehicle control during the time indicated. No agents were administered to stimulate contraction. Veh, n = 5; ALV, n = 5. F: alverine (15 mg/kg) or vehicle control was given intraperitoneally to nonsensitized acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC)1a−/− mice, 30 min before measurement of airway resistance at increasing doses of methacholine. Veh, n = 3; ALV, n = 3. For all panels, *P < 0.05 for treatment in 2-way ANOVA.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we developed transcriptome signatures from the vagal ganglia of nonsensitized and OVA-sensitized WT and ASIC1a−/− mice to identify potential therapeutics for AHR and asthma. By treating OVA sensitization and loss of ASIC1a as “interventions,” we identified a subset of transcripts that were responsive to OVA sensitization in the vagal ganglia of WT mice, which upon loss of ASIC1a, were normalized (signature 1). For comparison, we developed signatures from previously published transcriptomes of OVA-sensitized WT mouse lung tissues (signature 2) (12) and from endobronchial biopsies of human asthmatics (signature 3) (100). The use of those transcript signatures to query CMAP revealed many compounds that have already been investigated for AHR and some that are currently used as asthma therapeutics. Of particular interest, only signature 1, which was derived from vagal ganglia, identified two clinical agents used to treat asthma (flunisolide, isoetarine). Thus transcriptome profiling of vagal ganglia might be a novel means to discover potential asthma therapeutics.

In our study, we hypothesized that the probing of the vagal ganglia transcriptome might reveal agents important for alleviating AHR with mechanisms independent of dampening inflammation. Indeed, we were able to find several agents. It is possible that the airway tissues used in our study were dominated by inflammatory-induced changes, whereas the vagal ganglia were not. In this case, one might predict that a greater number of beneficial agents, independent of inflammation, would be detected by the vagal ganglia transcriptome compared with the airway tissues. Thus although our study was not designed to answer this question, it is possible that tissue responses to inflammation ultimately impacted the types of drugs identified by each transcriptome.

Many of the compounds identified by signature 1 were beneficial, independent of whether they mimicked or reversed signature 1. This finding suggests that the majority of transcripts comprising signature 1 were likely compensatory and/or potentially protective in nature. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated that a sublethal stressor in the nervous system can produce a “damage refractory” state that protects the nervous system from subsequent injury (preconditioning and tolerance) (38, 78, 84). In rats preconditioned with brief seizures, the transcriptional response of the hippocampus to a subsequent seizure is characterized by a neuroprotective suppression of Ca2+ signaling (38). Thus it is possible that the vagal ganglia display a similar preconditioning effect during the antigen-exposure process. If true, then perhaps the examination of the temporal pattern of changes in gene expression, as opposed to a single time point, might provide additional insight.

The DisGeNET analysis revealed asthma-associated genes in each signature. Only one gene, solute carrier family 26, member 4, overlapped between signatures 2 and 3. All other asthma-associated genes were unique across signatures. Given this distinct pattern, it is interesting to speculate whether signatures 1–3 contain a unique, predictive value regarding asthma symptoms and/or response to asthma therapeutics. It is also interesting to consider whether some genes comprising each signature, that are not currently associated with asthma, might be new asthma candidate genes and/or biomarkers.

We identified alverine citrate as a bronchodilator that reduced airway constriction and decreased airway resistance. Alverine citrate is approved in Europe and other countries for treating irritable bowel syndrome (98). Earlier reports indicated that alverine citrate is not a narcotic or anticholinergic (70, 92). Interestingly, subsequent studies determined that alverine citrate blocks Ca2+ entry into smooth muscle and neurons (8). Two additional reports found that alverine citrate blocked action potentials and reduced vagal sensory nerve hyperexcitability (1, 23). We speculate that alverine citrate’s prevention of bronchoconstriction likely involves vagal neurons and/or airway smooth muscle, probably by inhibiting Ca2+ channels. It is also interesting to consider the potential benefit of alverine citrate for people with asthma. Alverine citrate is prescribed for nonasthmatic conditions, is a readily available oral agent, and has a good safety profile. Although no data are presently available to evaluate whether alverine citrate modifies AHR in humans, we speculate that it, or perhaps its derivatives, may provide relief and have a beneficial effect in some people with asthma. Perhaps those that are resistant to anti-inflammatory therapy would benefit most.

A potential limitation of our study is that we examined the entire vagal ganglia, including any satellite cells, blood cells, collagen cells, and/or immune cells (42) that might be present at the time of ganglia dissection. However, this approach allowed for the probing of the entire ganglia and was more similar to strategies used to assess transcriptomes of airway tissues (i.e., mixed cell types) (12, 100). The presumed diversity of cells present in the ganglia at the time of dissection might also explain the vast array of compounds that were identified by the vagal ganglia transcriptome. We also recognize that by not querying airway-specific vagal neurons, some signal detected in the vagal ganglia might have arisen from esophageal sensitization and not airway sensitization (101). Thus whereas single-cell RNA sequencing has challenges that can diminish information obtained (36, 69), it is possible that the performance of single-cell RNA sequencing on pulmonary-innervating neurons might provide neuron-specific transcripts important for AHR and eliminate potential noise (96).

It is also important to note that signatures 1 and 2 were derived from mice, whereas CMAP is a collection of gene signatures derived from human cell lines (41). Yet even with species differences, we were able to identify two clinical drugs for treating asthma using signature 1. Others have also found beneficial the use of mouse data to query CMAP for human conditions (33). Another consideration is that the cell lines in CMAP were cancer cell lines (41). Perhaps a more useful data set would be one derived from a panel of drugs applied to vagal ganglia neurons; however, to the best of our knowledge, such a data set does not exist.

We used ASIC1a−/− mice as a tool to identify potential therapeutics. Yet it is possible that the involvement of nerves in asthma may be via distinct receptors and mechanisms that were not considered in the current study (10, 88, 91, 96). An additional consideration is that whereas OVA sensitization is a good model for allergic inflammation, it might not fully recapitulate the human condition of asthma (77). However, the use of transcripts derived from endobronchial biopsies of human asthmatics (100) to query CMAP did not yield any clinical agents useful for treating asthma, whereas use of transcripts derived from the OVA-sensitization model did. Therefore, whereas care should be taken in extrapolating our findings to a clinical perspective, our data suggest that the OVA-sensitization model can provide meaningful and clinically relevant information regarding asthma therapeutics.

Finally, we identified several additional compounds, not previously linked to asthma and not yet tested in airway disease. Perhaps some of them might be useful for attenuating AHR and treating asthma or other airway diseases. It is also possible that the adaption of a similar strategy that was developed for the vagal ganglia and the application of it to other tissues might reveal unanticipated insight into asthma pathogenesis and potential therapeutics.

GRANTS

This work was supported, in part, by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants 1K99-HL-119560-01A1 and 4R00-HL-119560-03 (to L. R. Reznikov) and 1P01-HL-091842 (to M. J. Welsh), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant 10T2TR001983-01 (to L. R. Reznikov), America Asthma Foundation (to D. A. Stoltz), and Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust. M. J. Welsh is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.R.R., D.K.M., M.A.A., N.L.B., T.B.B., D.A.S., and M.J.W. conceived and designed research; L.R.R., D.K.M., M.A.A., S.-P.K., Y.-S.J.L., N.L.B., and M.P. performed experiments; L.R.R., N.L.B., and T.B.B. analyzed data; L.R.R., D.K.M., M.A.A., S.-P.K., Y.-S.J.L., N.L.B., T.B.B., and M.J.W. interpreted results of experiments; L.R.R. prepared figures; L.R.R., D.K.M., M.A.A., D.A.S., and M.J.W. drafted manuscript; L.R.R., D.K.M., M.A.A., S.-P.K., Y.-S.J.L., N.L.B., T.B.B., M.P., D.A.S., and M.J.W. edited and revised manuscript; L.R.R., D.K.M., M.A.A., S.-P.K., Y.-S.J.L., N.L.B., T.B.B., M.P., D.A.S., and M.J.W. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplemental Data

Table S1: Transcripts induced or repressed by OVA-sensitization in wild-type and ASIC1a-/- mice - .xlsx (95 KB)

Table S2: Transcripts differentially expressed in the vagal ganglia of saline-treated wild-type (WT) and ASIC1a-/- mice - .xlsx (49 KB)

Table S3: Transcripts induced or repressed by OVA-sensitization in wild-type (WT) mouse lung or bronchial samples from human asthmatics. Blue indicates transcripts in which Affymetrix identifiers wer - .xlsx (60 KB)

Table S4: DisGeNET analysis of Signature #1 - .xlsx (17 KB)

Table S5: DisGeNET analysis of Signature #2 - .xlsx (15 KB)

Table S6: DisGeNET analysis of Signature #3 - .xlsx (11 KB)

Table S7: Full DisGeNET analysis of transcripts comprising Signature #1 - .xls (3 MB)

Table S8: Full DisGeNET analysis of transcripts comprising Signature #2 - .xls (7 MB)

Table S9: Full DisGeNET analysis of transcripts comprising Signature #3 - .xls (4 MB)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Giselle Edwards, Jennifer Bair, Dr. Kevin Knutson, the University of Iowa DNA Core, Paul Naumann, Dan Grigsby, Austin Stark, and Katelyn Davis. We also thank Dr. Kalina Atanasova for helpful comments and suggestions in the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abysique A, Lucchini S, Orsoni P, Mei N, Bouvier M. Effects of alverine citrate on cat intestinal mechanoreceptor responses to chemical and mechanical stimuli. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 13: 561–566, 1999. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ananth J. Letter: antiasthmatic effect of amitriptyline. Can Med Assoc J 110: 1131-passim, 1974. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee A, Trivedi CM, Damera G, Jiang M, Jester W, Hoshi T, Epstein JA, Panettieri RA Jr. Trichostatin A abrogates airway constriction, but not inflammation, in murine and human asthma models. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 46: 132–138, 2012. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0276OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassareo PP, Bassareo V, Manca D, Fanos V, Mercuro G. An old drug for use in the prevention of sudden infant unexpected death due to vagal hypertonia. Eur J Pediatr 170: 1569–1575, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumanis EA, Kalnina IE, Kaminka ME, Mashkovsky MD, Gorkin VZ. Modification of the activity of mitochondrial monoamine oxidases in vitro and in vivo. Agents Actions 11: 685–692, 1981. doi: 10.1007/BF01978790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernareggi MM, Belvisi MG, Patel H, Barnes PJ, Giembycz MA. Anti-spasmogenic activity of isoenzyme-selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors in guinea-pig trachealis. Br J Pharmacol 128: 327–336, 1999. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blatter J, Han YY, Forno E, Brehm J, Bodnar L, Celedón JC. Folate and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188: 12–17, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0317PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouvier M, Grimaud JC, Abysique A, Chiarelli P. Effects of alverine on the spontaneous electrical activity and nervous control of the proximal colon of the rabbit. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 16: 334–338, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bush RK, Ehrlich EN, Reed CE. Thyroid disease and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 59: 398–401, 1977. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(77)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caceres AI, Brackmann M, Elia MD, Bessac BF, del Camino D, D’Amours M, Witek JS, Fanger CM, Chong JA, Hayward NJ, Homer RJ, Cohn L, Huang X, Moran MM, Jordt SE. A sensory neuronal ion channel essential for airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 9099–9104, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900591106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calvani M, Alessandri C, Sopo SM, Panetta V, Tripodi S, Torre A, Pingitore G, Frediani T, Volterrani A; Lazio Association of Pediatric Allergology (APAL) Study Group . Infectious and uterus related complications during pregnancy and development of atopic and nonatopic asthma in children. Allergy 59: 99–106, 2004. doi: 10.1046/j.1398-9995.2003.00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camateros P, Kanagaratham C, Henri J, Sladek R, Hudson TJ, Radzioch D. Modulation of the allergic asthma transcriptome following resiquimod treatment. Physiol Genomics 38: 303–318, 2009. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00057.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman DG, Irvin CG. Mechanisms of airway hyper-responsiveness in asthma: the past, present and yet to come. Clin Exp Allergy 45: 706–719, 2015. doi: 10.1111/cea.12506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi GS, Sung JM, Lee JW, Ye YM, Park HS. A case of occupational asthma caused by inhalation of vancomycin powder. Allergy 64: 1391–1392, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collier HO, Shorley PG. Analgesic antipyretic drugs as antagonists of bradykinin. Br J Pharmacol Chemother 15: 601–610, 1960. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1960.tb00288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collipp PJ, Goldzier S III, Weiss N, Soleymani Y, Snyder R. Pyridoxine treatment of childhood bronchial asthma. Ann Allergy 35: 93–97, 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook DP, Adam RJ, Zarei K, Deonovic B, Stroik MR, Gansemer ND, Meyerholz DK, Au KF, Stoltz DA. CF airway smooth muscle transcriptome reveals a role for PYK2. JCI Insight 2: e95332, 2017. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.95332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook DP, Rector MV, Bouzek DC, Michalski AS, Gansemer ND, Reznikov LR, Li X, Stroik MR, Ostedgaard LS, Abou Alaiwa MH, Thompson MA, Prakash YS, Krishnan R, Meyerholz DK, Seow CY, Stoltz DA. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in sarcoplasmic reticulum of airway smooth muscle: implications for airway contractility. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193: 417–426, 2016. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201508-1562OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daoud A, Gloria CJ, Taningco G, Hammerschlag MR, Weiss S, Gelling M, Roblin PM, Joks R. Minocycline treatment results in reduced oral steroid requirements in adult asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc 29: 286–294, 2008. doi: 10.2500/aap.2008.29.3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Decimo F, Maiello N, Miraglia Del Giudice M, Amelio R, Capristo C, Capristo AF. High-dose inhaled flunisolide versus budesonide in the treatment of acute asthma exacerbations in preschool-age children. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 22: 363–370, 2009. doi: 10.1177/039463200902200213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhanoa J, Natu M, Massey S. Worsening of steroid depending bronchial asthma following rifampicin administration. J Assoc Physicians India 46: 242, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan W, Aguinaldo Datiles AM, Leung BP, Vlahos CJ, Wong WS. An anti-inflammatory role for a phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 in a mouse asthma model. Int Immunopharmacol 5: 495–502, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ducreux C, Clerc N, Puizillout JJ. Effects of alverine on electrical properties of vagal afferent neurons in isolated rabbit nodose ganglion. In: Primary Sensory Neuron. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1997, p. 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans CM, Kim K, Tuvim MJ, Dickey BF. Mucus hypersecretion in asthma: causes and effects. Curr Opin Pulm Med 15: 4–11, 2009. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32831da8d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans CM, Raclawska DS, Ttofali F, Liptzin DR, Fletcher AA, Harper DN, McGing MA, McElwee MM, Williams OW, Sanchez E, Roy MG, Kindrachuk KN, Wynn TA, Eltzschig HK, Blackburn MR, Tuvim MJ, Janssen WJ, Schwartz DA, Dickey BF. The polymeric mucin Muc5ac is required for allergic airway hyperreactivity. Nat Commun 6: 6281, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ezeamuzie CI, Sukumaran J, Philips E. Effect of wortmannin on human eosinophil responses in vitro and on bronchial inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in Guinea pigs in vivo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 1633–1639, 2001. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.9.2101104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan G, Wang B, Liu C, Li D. Prenatal paracetamol use and asthma in childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 45: 528–533, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang LB, Morton RF, Wang AL, Lee LY. Bronchoconstriction and delayed rapid shallow breathing induced by cigarette smoke inhalation in anesthetized rats. Lung 169: 153–164, 1991. doi: 10.1007/BF02714151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feinsilver O, Cho YW, Aviado DM. Pharmacology of a new antianginal drug: perhexiline. 3. Bronchopulmonary system in the dog and humans. Chest 58: 558–561, 1970. doi: 10.1378/chest.58.6.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibson-Corley KN, Olivier AK, Meyerholz DK. Principles for valid histopathologic scoring in research. Vet Pathol 50: 1007–1015, 2013. doi: 10.1177/0300985813485099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Global Inititative for Asthma Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (Online) https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/GINA-Appendix-2016-final.pdf. [Last accessed, June 2018].

- 32.Gross NJ, Skorodin MS. Anticholinergic, antimuscarinic bronchodilators. Am Rev Respir Dis 129: 856–870, 1984. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guedj F, Pennings JL, Massingham LJ, Wick HC, Siegel AE, Tantravahi U, Bianchi DW. An integrated human/murine transcriptome and pathway approach to identify prenatal treatments for Down syndrome. Sci Rep 6: 32353, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep32353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hargreave FE, Ramsdale EH, Kirby JG, O’Byrne PM. Asthma and the role of inflammation. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl 147: 16–21, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hellgren J, Torén K, Balder B, Palmqvist M, Löwhagen O, Karlsson G. Increased nasal mucosal swelling in subjects with asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 32: 64–69, 2002. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-0477.2001.01253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Islam S, Zeisel A, Joost S, La Manno G, Zajac P, Kasper M, Lönnerberg P, Linnarsson S. Quantitative single-cell RNA-seq with unique molecular identifiers. Nat Methods 11: 163–166, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang SP, Liang RY, Zeng ZY, Liu QL, Liang YK, Li JG. Effects of antireflux treatment on bronchial hyper-responsiveness and lung function in asthmatic patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 9: 1123–1125, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i5.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jimenez-Mateos EM, Hatazaki S, Johnson MB, Bellver-Estelles C, Mouri G, Bonner C, Prehn JH, Meller R, Simon RP, Henshall DC. Hippocampal transcriptome after status epilepticus in mice rendered seizure damage-tolerant by epileptic preconditioning features suppressed calcium and neuronal excitability pathways. Neurobiol Dis 32: 442–453, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karakaya G, Kalyoncu AF. Metamizole intolerance and bronchial asthma. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 30: 267–272, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0546(02)79136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kunkel SD, Suneja M, Ebert SM, Bongers KS, Fox DK, Malmberg SE, Alipour F, Shields RK, Adams CM. mRNA expression signatures of human skeletal muscle atrophy identify a natural compound that increases muscle mass. Cell Metab 13: 627–638, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lamb J, Crawford ED, Peck D, Modell JW, Blat IC, Wrobel MJ, Lerner J, Brunet JP, Subramanian A, Ross KN, Reich M, Hieronymus H, Wei G, Armstrong SA, Haggarty SJ, Clemons PA, Wei R, Carr SA, Lander ES, Golub TR. The connectivity map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science 313: 1929–1935, 2006. doi: 10.1126/science.1132939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le DD, Rochlitzer S, Fischer A, Heck S, Tschernig T, Sester M, Bals R, Welte T, Braun A, Dinh QT. Allergic airway inflammation induces the migration of dendritic cells into airway sensory ganglia. Respir Res 15: 73, 2014. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leitch IM, Boura AL, Edwards P, King RG, Rawlow A, Rechtman MP. In-vivo pharmacological studies of 2-N-carboxamidinonormianserin, a histamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine antagonist lacking central effects. J Pharm Pharmacol 44: 841–846, 1992. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1992.tb03216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lenox WC, Hirshman CA. Amrinone attenuates airway constriction during halothane anesthesia. Anesthesiology 79: 789–794, 1993. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199310000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lew DB, Herrod HG, Crawford LV. Combination of atropine and isoetharine aerosol therapy in pediatric acute asthma. Ann Allergy 64: 195–200, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Litonjua AA, Carey VJ, Laranjo N, Harshfield BJ, McElrath TF, O’Connor GT, Sandel M, Iverson RE Jr, Lee-Paritz A, Strunk RC, Bacharier LB, Macones GA, Zeiger RS, Schatz M, Hollis BW, Hornsby E, Hawrylowicz C, Wu AC, Weiss ST. Effect of prenatal supplementation with vitamin D on asthma or recurrent wheezing in offspring by age 3 years: the VDAART Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 315: 362–370, 2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu C, Cui Z, Wang S, Zhang D. CD93 and GIPC expression and localization during central nervous system inflammation. Neural Regen Res 9: 1995–2001, 2014. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.145383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lockhart A, Slutsky AS. Furosemide and loop diuretics in human asthma. Chest 106: 244–249, 1994. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.1.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGowan SE, Holmes AJ, Smith J. Retinoic acid reverses the airway hyperresponsiveness but not the parenchymal defect that is associated with vitamin A deficiency. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 286: L437–L444, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00158.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyerholz DK, Reznikov LR. Simple and reproducible approaches for the collection of select porcine ganglia. J Neurosci Methods 289: 93–98, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meyerholz DK, Stoltz DA, Pezzulo AA, Welsh MJ. Pathology of gastrointestinal organs in a porcine model of cystic fibrosis. Am J Pathol 176: 1377–1389, 2010. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moscato G, Galdi E, Scibilia J, Dellabianca A, Omodeo P, Vittadini G, Biscaldi GP. Occupational asthma, rhinitis and urticaria due to piperacillin sodium in a pharmaceutical worker. Eur Respir J 8: 467–469, 1995. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murai T, Sanai K, Miyao Y, Kanai T. Pharmacological effects of urapidil on bronchospasm, myocardial hypoxia and postural hypotension in experimental animals. J Hypertens Suppl 6, Sup 2: S55–S58, 1988. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198812001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mushaben EM, Kramer EL, Brandt EB, Khurana Hershey GK, Le Cras TD. Rapamycin attenuates airway hyperreactivity, goblet cells, and IgE in experimental allergic asthma. J Immunol 187: 5756–5763, 2011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Narala VR, Ranga R, Smith MR, Berlin AA, Standiford TJ, Lukacs NW, Reddy RC. Pioglitazone is as effective as dexamethasone in a cockroach allergen-induced murine model of asthma. Respir Res 8: 90, 2007. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nowotka MM, Gaulton A, Mendez D, Bento AP, Hersey A, Leach A. Using ChEMBL web services for building applications and data processing workflows relevant to drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov 12: 757–767, 2017. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2017.1339032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Okada H, Ohnishi T, Hirashima M, Fujita J, Yamaji Y, Takahara J, Todani T. Anti-asthma effect of an antiviral drug, acyclovir: a clinical case and experimental study. Clin Exp Allergy 27: 431–437, 1997. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1997.tb00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Padrid PA, Mathur M, Li X, Herrmann K, Qin Y, Cattamanchi A, Weinstock J, Elliott D, Sperling AI, Bluestone JA. CTLA4Ig inhibits airway eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness by regulating the development of Th1/Th2 subsets in a murine model of asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 18: 453–462, 1998. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.4.3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Piñero J, Bravo À, Queralt-Rosinach N, Gutiérrez-Sacristán A, Deu-Pons J, Centeno E, García-García J, Sanz F, Furlong LI. DisGeNET: a comprehensive platform integrating information on human disease-associated genes and variants. Nucleic Acids Res 45: D833–D839, 2017. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Post MJ, te Biesebeek JD, Wemer J, van Rooij HH, Porsius AJ. Effects of milrinone, sulmazole and theophylline on adenosine enhancement of antigen-induced bronchoconstriction and mediator release in rat isolated lungs. Pulm Pharmacol 4: 239–246, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0952-0600(91)90017-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prakash YS. Airway smooth muscle in airway reactivity and remodeling: what have we learned? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 305: L912–L933, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00259.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Price MP, Lewin GR, McIlwrath SL, Cheng C, Xie J, Heppenstall PA, Stucky CL, Mannsfeldt AG, Brennan TJ, Drummond HA, Qiao J, Benson CJ, Tarr DE, Hrstka RF, Yang B, Williamson RA, Welsh MJ. The mammalian sodium channel BNC1 is required for normal touch sensation. Nature 407: 1007–1011, 2000. doi: 10.1038/35039512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pye S, Pavord I, Wilding P, Bennett J, Knox A, Tattersfield A. A comparison of the effects of inhaled furosemide and ethacrynic acid on sodium-metabisulfite-induced bronchoconstriction in subjects with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 151: 337–339, 1995. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.2.7842188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rebuck AS, Chapman KR, Braude AC. Anticholinergic therapy of asthma. Chest 82, Suppl: 55S–57S, 1982. doi: 10.1378/chest.82.1.55S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reddy D, Little FF. Glucocorticoid-resistant asthma: more than meets the eye. J Asthma 50: 1036–1044, 2013. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2013.831870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reznikov LR, Meyerholz DK, Adam RJ, Abou Alaiwa M, Jaffer O, Michalski AS, Powers LS, Price MP, Stoltz DA, Welsh MJ. Acid-sensing ion channel 1a contributes to airway hyperreactivity in mice. PLoS One 11: e0166089, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Riffo-Vasquez Y, Ligeiro de Oliveira AP, Page CP, Spina D, Tavares-de-Lima W. Role of sex hormones in allergic inflammation in mice. Clin Exp Allergy 37: 459–470, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Royce SG, Dang W, Ververis K, De Sampayo N, El-Osta A, Tang ML, Karagiannis TC. Protective effects of valproic acid against airway hyperresponsiveness and airway remodeling in a mouse model of allergic airways disease. Epigenetics 6: 1463–1470, 2011. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.12.18396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saliba AE, Westermann AJ, Gorski SA, Vogel J. Single-cell RNA-seq: advances and future challenges. Nucleic Acids Res 42: 8845–8860, 2014. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Salim EF, Ebert WR. Qualitative and quantitative tests for alverine citrate. J Pharm Sci 56: 1162–1163, 1967. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600560924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sánchez-Mendoza ME, Castillo-Henkel C, Navarrete A. Relaxant action mechanism of berberine identified as the active principle of Argemone ochroleuca Sweet in guinea-pig tracheal smooth muscle. J Pharm Pharmacol 60: 229–236, 2008. doi: 10.1211/jpp.60.2.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sanders PN, Koval OM, Jaffer OA, Prasad AM, Businga TR, Scott JA, Hayden PJ, Luczak ED, Dickey DD, Allamargot C, Olivier AK, Meyerholz DK, Robison AJ, Winder DG, Blackwell TS, Dworski R, Sammut D, Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Pope RM, Miller FJ Jr, Dibbern ME, Haitchi HM, Mohler PJ, Howarth PH, Zabner J, Kline JN, Grumbach IM, Anderson ME. CaMKII is essential for the proasthmatic effects of oxidation. Sci Transl Med 5: 195ra97, 2013. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sato T, Hirota K, Matsuki A, Zsigmond EK, Rabito SF. Droperidol inhibits tracheal contraction induced by serotonin, histamine or carbachol in guinea pigs. Can J Anaesth 43: 172–178, 1996. doi: 10.1007/BF03011259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schuller DE. Prophylaxis of otitis media in asthmatic children. Pediatr Infect Dis 2: 280–283, 1983. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shang S, Tan DS. Advancing chemistry and biology through diversity-oriented synthesis of natural product-like libraries. Curr Opin Chem Biol 9: 248–258, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shi Y, Dai J, Liu H, Li RR, Sun PL, Du Q, Pang LL, Chen Z, Yin KS. Naringenin inhibits allergen-induced airway inflammation and airway responsiveness and inhibits NF-kappaB activity in a murine model of asthma. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 87: 729–735, 2009. doi: 10.1139/Y09-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shin YS, Takeda K, Gelfand EW. Understanding asthma using animal models. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 1: 10–18, 2009. doi: 10.4168/aair.2009.1.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]