Abstract

While primary cystic fibrosis (CF) and non-CF human bronchial epithelial basal cells (HBECs) accurately represent in vivo phenotypes, one barrier to their wider use has been a limited ability to clone and expand cells in sufficient numbers to produce rare genotypes using genome-editing tools. Recently, conditional reprogramming of cells (CRC) with a Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor and culture on an irradiated fibroblast feeder layer resulted in extension of the life span of HBECs, but differentiation capacity and CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) function decreased as a function of passage. This report details modifications to the standard HBEC CRC protocol (Mod CRC), including the use of bronchial epithelial cell growth medium, instead of F medium, and 2% O2, instead of 21% O2, that extend HBEC life span while preserving multipotent differentiation capacity and CFTR function. Critically, Mod CRC conditions support clonal growth of primary HBECs from a single cell, and the resulting clonal HBEC population maintains multipotent differentiation capacity, including CFTR function, permitting gene editing of these cells. As a proof-of-concept, CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing and cloning were used to introduce insertions/deletions in CFTR exon 11. Mod CRC conditions overcome many barriers to the expanded use of HBECs for basic research and drug screens. Importantly, Mod CRC conditions support the creation of isogenic cell lines in which CFTR is mutant or wild-type in the same genetic background with no history of CF to enable determination of the primary defects of mutant CFTR.

Keywords: conditional reprogramming, CRISPR, cystic fibrosis, human bronchial epithelial cells, ROCK inhibitor

INTRODUCTION

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a common recessive genetic disorder characterized by abnormally viscous secretions in multiple organ systems, but lung obstruction is the primary cause of morbidity and mortality in CF patients (1, 7). Although defects in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), an anion channel, were identified as the cause of CF in 1989 (25), there remains no effective treatment to reverse the early mortality. Because of improvements in diagnosis and clinical treatment, the average life expectancy of CF patients has doubled but remains only about half the average human life expectancy worldwide (United Nations World Population Prospects 2012 Revision). The therapeutic regimen for CF patients is rigorous, costly, and time consuming (up to 3 h physical therapy/day) and markedly impairs quality of life (11).

Novel techniques to culture primary human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) long term would provide powerful tools for the study of CF lung pathophysiology and development of drug therapies. Primary CF HBECs have proven central to the clinical development pathway for CF, including the development of Kalydeco (ivacaftor) to treat a subset of CF patients with the G551D mutation (4%) and Orkambi (lumacaftor/ivacaftor) to treat CF patients homozygous for the ∆F508 mutation (~50%). To create in vitro models of human CF disease phenotypes, many lung epithelial cell lines have been developed. Primary cells isolated from tissue most closely represent in vivo conditions, but CF tissue is difficult to access and often infected with bacteria and fungi, and most of the rarer CF genotypes are underrepresented. To address these issues, several CF and non-CF lung epithelial cells have been immortalized by overexpression of viral oncogenes or the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) gene (12). Immortalization allows for production of an exponential number of cells, permitting long-term experimentation with stable cell reagents (27). However, CF tracheobronchial glandular cells immortalized by SV40 transfection, CFSMEo− and 6CFSMEo, produce residual amounts of CFTR mRNA and do not establish transepithelial resistance at the air-liquid interface (ALI) (5), similar to a variety of CF HBECs immortalized by SV40 (12). Zabner and colleagues used human papilloma virus E6/E7 and hTERT to create three CF HBEC lines (CuFi-1, -3, and -4) and one non-CF HBEC line (NuLi-1) (33). While the NuLi-1 cell line was able to grow for an extended number of passages in vitro compared with unimmortalized HBECs, it exhibited a linear and rapid decrease in CFTR function as well as a decrease in ciliated cell formation at late passages in ALI cultures.

Recently, viral oncogene-independent methods whereby endogenous proteins that control cell cycle are overexpressed along with hTERT have been used to immortalize HBECs (8, 21). While overexpression of hTERT in combination with other genes effectively immortalizes HBECs, the resulting cells lose the ability to differentiate into different cell types and express CFTR and also exhibit genetic instability. For example, Fulcher et al. created a set of three CF (ΔF508/ΔF508) and three non-CF life-extended HBECs by overexpressing the protooncogene B cell Moloney murine leukemia retrovirus-specific integration site 1 (Bmi1) and hTERT with lentiviral vectors (8). While the cells grow in culture for ~50 population doublings (PDs), the six cell lines differentiated at the ALI to an in vitro epithelium are dominated by goblet cells with few ciliated cells.

Additionally, we also immortalized several normal HBEC lines with expression of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (Cdk4) and hTERT by retroviral transfection (21) that grow in culture for >100 PDs. While these immortalized HBECs maintain the ability to differentiate into multiple organotypic structures dictated by the extracellular environment (6), CFTR mRNA expression in ALI cultures is low (data not shown). Thus, while expression of hTERT in combination with other genes effectively immortalizes HBECs, the resulting cells lose the ability to differentiate and express CFTR and also exhibit genetic instability.

More recently, a genetic modification-independent technique consisting of a combination of a Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor and coculture of primary HBECs with irradiated fibroblasts resulted in greatly extended cell culture proliferation (15). The technique conditionally maintains epithelial cells in a stem cell-like state that enables long-term growth. Conditional reprogramming is rapidly reversible upon removal of both the ROCK inhibitor and the fibroblast feeder layer, permitting the cells to differentiate into an in vitro epithelium with ciliated and goblet cells (28). While the life span of conditionally reprogrammed HBECs (CRCs) has been shown to be extended, morphology of the resulting ALI cultures is altered and, again, CFTR function declines with passage in culture (10), although not to the same extent as in immortalized HBEC lines. Therefore, a need remains for a method that extends the life span of CF and non-CF HBECs and maintains primary-like cell characteristics, including multipotent differentiation potential and CFTR expression.

The objectives of the present study were twofold: 1) to determine a set of conditions (modified CRC) that not only extend in vitro life span but preserve differentiation capacity, including CFTR function, and 2) to test if the modified CRC method can support cloning for genome editing with CRISPR/Cas9 to introduce CFTR mutations in non-CF HBECs.

Building on methods previously reported (10, 15, 28), we modified the standard CRC protocol to allow for the long-term growth of normal and CF HBECs and maintain the capacity to differentiate at the ALI for ≥47 PDs (more than sufficient time to isolate genome-edited clones and expand them for basic research/drug screens). These methods significantly extend the life span in vitro of primary-like cells with characteristics similar to those freshly isolated from lung tissue, making them primary-like, but with the advantage of being able to undergo an extended number of passages. These cells more accurately reflect lung tissue than other cells previously used to study CF that were derived from lung cancer tumors or altered by expression of viral oncogenes or telomerase.

CRISPR/Cas9 is a genome-editing technique derived from a microbial adaptive immune response to foreign DNA (17) in which RNA with complementary sequence to target genomic DNA guides the Cas9 nuclease to make double-stranded breaks (16). Double-stranded breaks repaired by error-prone nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) will likely result in knockout of the target gene. Alternatively, specific mutations can be introduced or repaired when homologous sequences are provided as a template for high-fidelity homologous recombination. CRISPR/Cas9 has been used successfully to edit the genomes of mammalian cells (22), including correction of mutant CFTR in human intestinal stem cell organoids (26) and lung epithelial cells generated from CF patient-induced pluripotent stem cells (4). Genome editing holds great promise for discovery of therapeutic interventions for treatment of patients with CF. However, a limiting step in using CRISPR/Cas9 editing is that cells must be able to proliferate long-term to allow identification of specific clones with introduced mutations. HBECs immortalized with telomerase (8, 21, 33) are a less-than-ideal starting reagent, since these cells rapidly lose appropriate cilia-to-goblet cell ratios upon differentiation and have an altered gene expression profile. Thus an improved approach would be to use primary normal and CF HBECs capable of long-term clonal proliferation in vitro that, upon differentiation, maintain CFTR function and appropriate cilia-to-goblet cell ratios. Here we show that the long-term proliferative ability of HBECs grown using our modified CRC protocol facilitates the introduction of CRISPR/Cas9 mutations in the CFTR gene of primary non-CF CRCs.

METHODS

Conventional culture of primary HBECs.

Primary CF and non-CF HBECs were obtained from the CF Center Tissue Procurement and Cell Culture Core at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Marisco Lung Institute or were harvested and cultured from CF lung explant tissue under a University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Institutional Review Board-approved protocol (no. CR00013395/STU052011020). The source of lung explant tissue and established cell lines, along with donor characteristics, are outlined in Table 2. Standard published protocols for HBEC expansion were followed with some minor modifications (9). Passage 1 cells were expanded twice in bronchial epithelial cell growth medium (BEGM; Lonza, Walkersville, MD), a 1:1 mixture of BEGM-DMEM-high glucose (GE Healthcare, Logan, UT) supplemented with a SingleQuots kit (Lonza), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-amphotericin B (Gemini Bioproducts, West Sacramento, CA). All primary cells tested negative for Mycoplasma. Dishes were coated with porcine gelatin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) only for initial thawing of cells. HBECs were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2-21% atmospheric O2 or in tri-gas chambers with 2% O2-7% CO2-91% N2 at 37°C, as described previously (32).

Table 2.

Demographics of CF and non-CF donors

| Donor | NHBEC1 | NHBEC2 | NHBEC3 | CFHBEC1 | CFHBEC2 | CFHBEC3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFTR genotype | Wild-type | Wild-type | Wild-type | ΔF508/ΔF508 | ΔF508/ΔF508 | ΔF508/ΔF508 |

| Sex | Male | Female | Male | Male | Female | Female |

| Age, yr | 21 | 19 | 19 | 27 | 28 | 22 |

| Cause of death | Head trauma | Head trauma | Head trauma | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Smoking status | Quit at age 20 | Smoker | Smoker | Nonsmoker | Nonsmoker | Nonsmoker |

| Source of tissue/primary cells | UNC | UNC | UNC | UTSW | UNC | UNC |

UNC, CF Tissue Procurement and Cell Culture Core at the Marisco Lung Institute, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; UTSW, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas.

3T3 J2 cell culture.

The 3T3 (J2 strain) Swiss mouse fibroblast cell line was purchased from Tissue Culture Shared Resource (Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Georgetown University) and tested negative for Mycoplasma. This cell line does not produce murine viruses and was irradiated (IR) at 30 Gy with γ-radiation to provide an IR fibroblast feeder layer.

HBEC coculture with IR 3T3 J2 feeder cells.

Primary HBECs were cocultured with IR 3T3 J2 feeder cells with several modifications (termed “modified CRC” or “Mod CRC”) to the published human bronchial epithelial CRC protocol (10), as described in Table 1 and the appendix. Briefly, freshly IR (30 Gy) 3T3 J2 cells and primary HBECs were seeded in a 1:1 ratio on uncoated dishes in BEGM supplemented with 5% FBS and 10 µM ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632; catalog no. ALX-270-333, Enzo Lifesciences, Farmingdale, NY). Cocultures were maintained in tri-gas chambers with 2% O2-7% CO2-91% N2 at 37°C. PDs were calculated as follows: cocultures were washed with 2% EDTA in PBS for 5 min at 37°C to remove fibroblasts and then washed briefly with PBS before trypsinization; HBECs were single-cell-suspended and counted with an automated cell counter (model TC20, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA); and the number of PDs gained at each passage was calculated as follows: n = log(NH/NI)/log2, where n is the number of PDs, NH is the number of cells harvested at the end of the growth period, and NI is the initial number of cells seeded. Gained PDs were cumulatively added at each passage and plotted against time for the growth curves.

Table 1.

Conditions used for coculture of HBECs

| Culture Condition |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional (Cnv) (9) | Standard (Std) CRC (10, 15, 28) | Modified (Mod) CRC (this report) | |

| T1, P0–P3+ | |||

| Expansion in 10-cm dishes | BEGM + 25 ng/ml EGF + 0.5 mg/ml BSA Purecol coating 21% O2 |

BEGM + 25 ng/ml EGF + 0.5 mg/ml BSA Purecol coating 21% O2 |

BEGM + 0.5 ng/ml EGF Porcine gelatin coating 2% O2 |

| T2, P3+ | |||

| Conditional reprogramming in dishes | N/A | F medium + 5% FBS + 5 µM Y | BEGM + 5% FBS + 10 µM Y |

| 2.6 × 106 cryopreserved IR 3T3 | 5 × 105 freshly IR 3T3 | ||

| HBECs cocultured at 1:3 or 1:4 with IR 3T3 | HBECs cocultured at 1:1 with IR 3T3 (5 × 105) | ||

| Purecol coating | No coating | ||

| 21% O2 | 2% O2 | ||

| T3, P5+ | |||

| Expansion on Transwell supports | BEGM Col IV coating 21% O2 |

F medium + 5% FBS + 5 µM Y Col IV coating 21% O2 |

BEGM + 10 µM Y Col IV coating 21% O2 |

| T4, P5+ | |||

| Differentiation on Transwell supports | BEGM + 0.5 ng/ml EGF + 0.11 mM CaCl2 + 0.01 mg/ml BPE + 0.5 mg/ml BSA | BEGM + 0.5 ng/ml EGF + 0.11 mM CaCl2 + 0.01 mg/ml BPE + 0.5 mg/ml BSA | BEGM + 0.5 ng/ml EGF + 0.11 mM CaCl2 + 0.1 mg/ml BPE |

| 21% O2 | 21% O2 | 21% O2 | |

Key differences between standard (Std) and modified (Mod) methods are underscored. HBECs, human bronchial epithelial cells; CRC, conditional reprogramming of cells; T, time; P, passage; BEGM, bronchial epithelial cell growth medium; Y, Y-27632; N/A, not applicable; IR 3T3, irradiated 3T3 fibroblasts; Col IV, collagen type IV; BPE, bovine pituitary extract.

ALI cultures.

Upon reaching semiconfluence (70–90%), HBECs at the desired passage were trypsinized before they were counted for seeding. HBECs were seeded onto human placental type IV collagen-coated (Sigma), 0.4-µm-pore Transwell membrane inserts (Costar, Corning, NY) at a density of 1 × 105 cells/cm2. HTS Transwell 24-well permeable supports (catalog no. 3378, Corning) were used for bioelectric analysis with a 24-channel transepithelial current clamp (TECC-24; EP Devices, Bertem, Belgium). In some experiments, six-well Transwell permeable supports (catalog no. 3450, Corning) were used for immunofluorescence staining. Cells were grown submerged in BEGM until they reached confluence (~3–5 days) in the absence of a feeder layer and in the presence of 10 µM Y-27632. Once the cells attained 100% confluence, the apical medium was removed and the cells were grown at the ALI with differentiation medium (Table 1; see appendix) added only to the basal compartment. For morphological and physiological comparison of standard (Std) with Mod CRC conditions in Figs. 3, 4, and 5A, cells were differentiated in the same differentiation medium with the lower 0.01 mg/ml bovine pituitary extract (BPE) concentration described for the Std CRC condition in Table 1. For Figs. 5B, 5C, 7G, 9B, and 9C, differentiation medium with the log-fold higher BPE concentration described for the Mod CRC condition in Table 1 was used. Basal medium was replaced three times per week, and cells were incubated at 37°C in 21% atmospheric O2 and 5% CO2; HBEC cultures were maintained at the ALI for 4–5 wk before analysis.

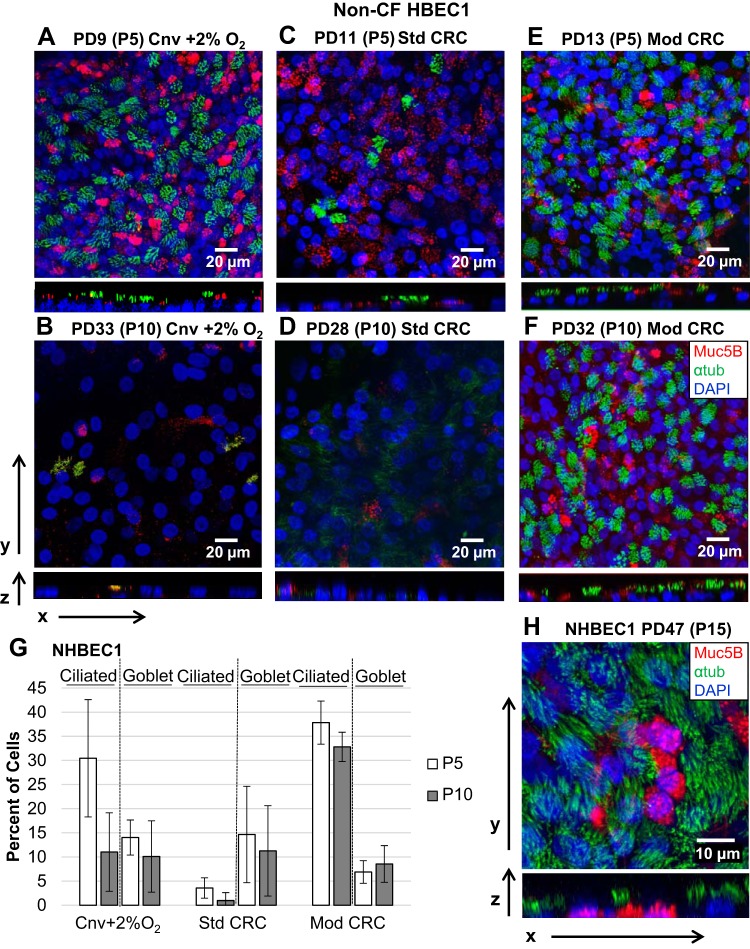

Fig. 3.

Morphology of air-liquid interface cultures of human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) from a non-CF donor (NHBEC1) differentiated after conventional (Cnv) expansion (with 2% O2) or standard (Std) or modified (Mod) conditionally reprogrammed cell (CRC) expansion. A–F: representative air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures differentiated from HBECs from the non-CF donor at indicated population doublings (PDs) and passages (P) and growth conditions were immunostained for mucin 5B (Muc5B; red)-expressing goblet cells and acetylated α-tubulin (αtub; green)-expressing ciliated cells and counterstained with DAPI (blue). Confocal z-stack images were acquired and merged in the xy or zy plane. G: percentage of resulting ciliated and goblet cells at the indicated passage and growth condition for HBECs from the non-CF donor. Values are means ± SD; n = 3 images. H: multichannel fluorescence confocal microscopy shows that HBECs from the non-CF donor expanded in modified CRC conditions maintain the capacity to differentiate to a well-differentiated epithelium at the ALI as late as 47 PDs (passage 15), with abundant ciliated and goblet cells.

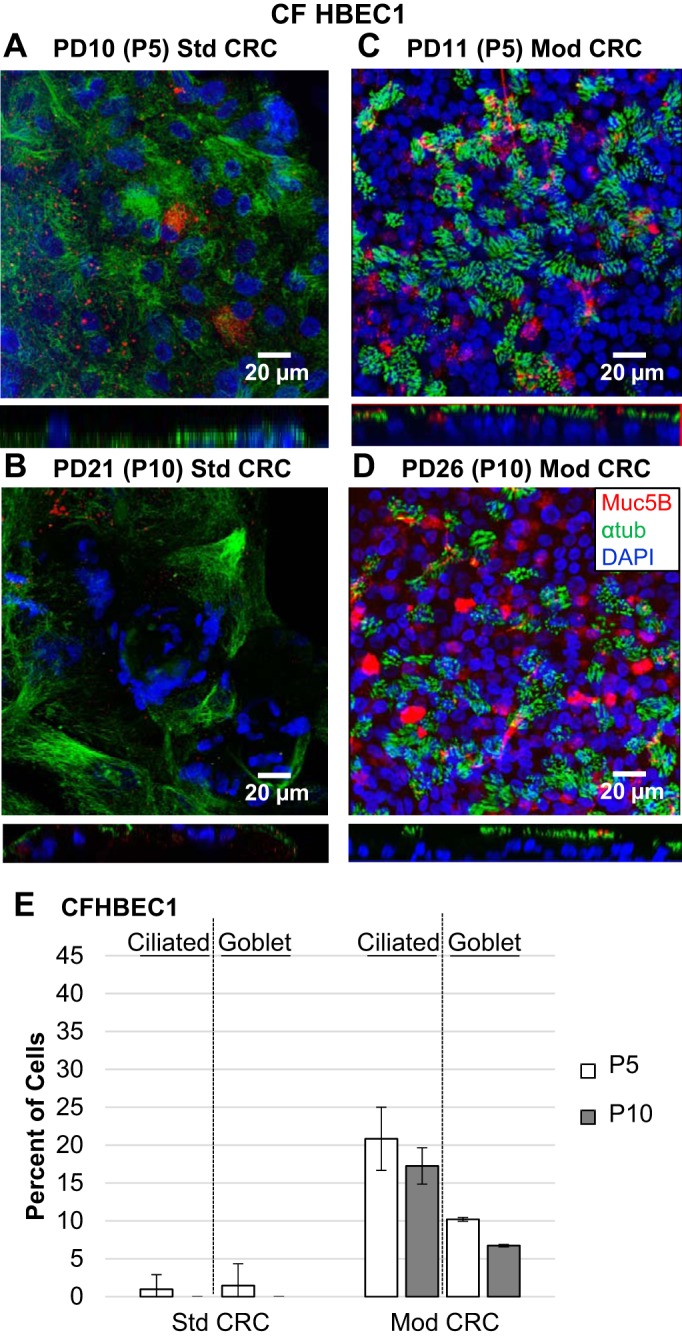

Fig. 4.

Morphology of air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures of HBECs from a CF donor (CFHBEC1) differentiated after standard (Std) or modified (Mod) conditionally reprogrammed cell (CRC) expansion. A–D: representative images of ALI cultures differentiated from HBECs from the CF donor at indicated population doubling (PD) and passage (P) and growth conditions were immunostained for mucin 5B (Muc5B; red)-expressing goblet and acetylated α-tubulin (αtub; green)-expressing ciliated cells and counterstained with DAPI (blue). Confocal z-stack images were acquired and merged in the xy or zy plane. E: percentage of resulting ciliated and goblet cells at the indicated passage and growth condition. Values are means ± SD; n = 3 images.

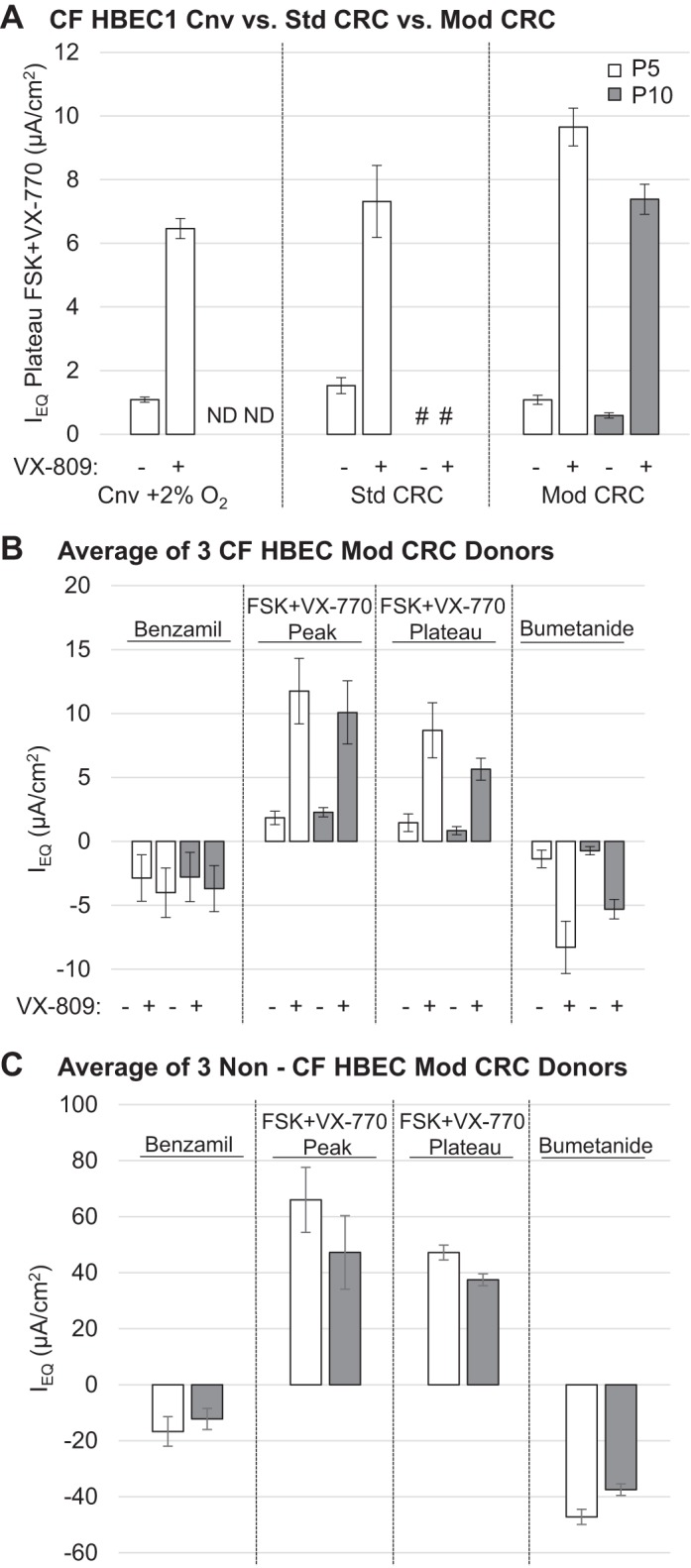

Fig. 5.

CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion of air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures of human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) from CF (CFHBEC1) and non-CF (NHBEC1) donors previously expanded in conventional (Cnv), standard (Std), and modified (Mod) conditionally reprogrammed cell (CRC) conditions. A: HBECs from donor CFHBEC1 expanded in Cnv + 2% O2, Std, and Mod CRC conditions at passages 5 (P5) and 10 (P10) were differentiated at the ALI for 4−5 wk, and CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion was analyzed by TECC-24 assay 48 h after treatment with 3 µM VX-809 (+) or DMSO (−). P5 = 10–13 population doublings (PDs); P10 = 20–26 PDs. Values are means ± SE; n = 3 experiments for Cnv and Mod CRC and 2 experiments for Std CRC because of unmeasurable results for transepithelial resistance (Rt) and equivalent current (Ieq) in the 3rd experiment, 6–8 replicates. #No detectable Rt/Ieq. ND, not determined. B: average Ieq of ALI cultures of HBECs from donors CFHBEC1, CFHBEC2, and CFHBEC3 previously expanded in Mod CRC conditions in response to benzamil, forskolin (FSK) + VX-770, or bumetanide 48 h after treatment with 3 µM VX-809 (+) or DMSO (−). P5 = 10–13 PDs; P10 = 20–26 PDs. Values are means ± SE for 1 experiment, 3 donors, 5–6 replicates. C: average Ieq of ALI cultures of HBECs from donors NHBEC1, NHBEC2, and NHBEC3 previously expanded in Mod CRC conditions in response to benzamil, FSK + VX-770, or bumetanide. P5 = 9–13 PDs; P10 = 27–29 PDs. Values are means ± SE for 1 experiment, 3 donors, 5–6 replicates.

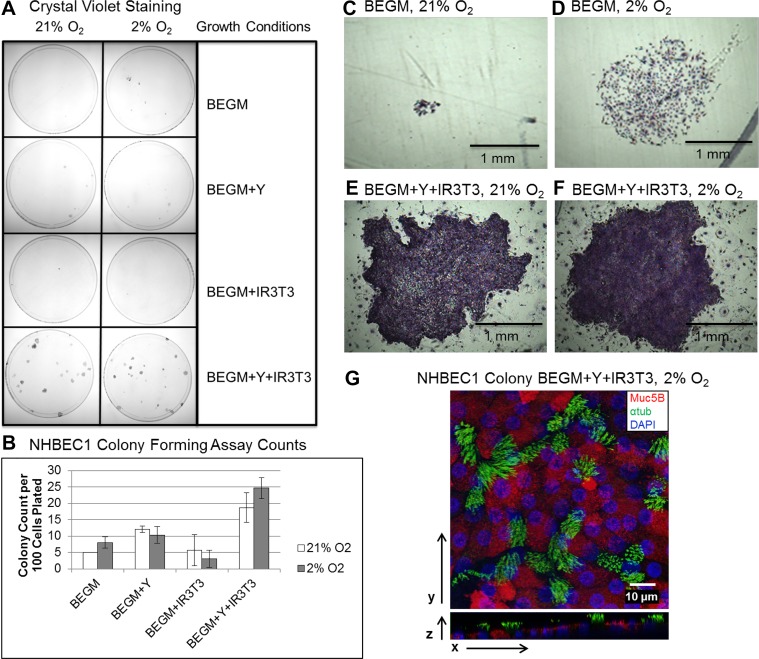

Fig. 7.

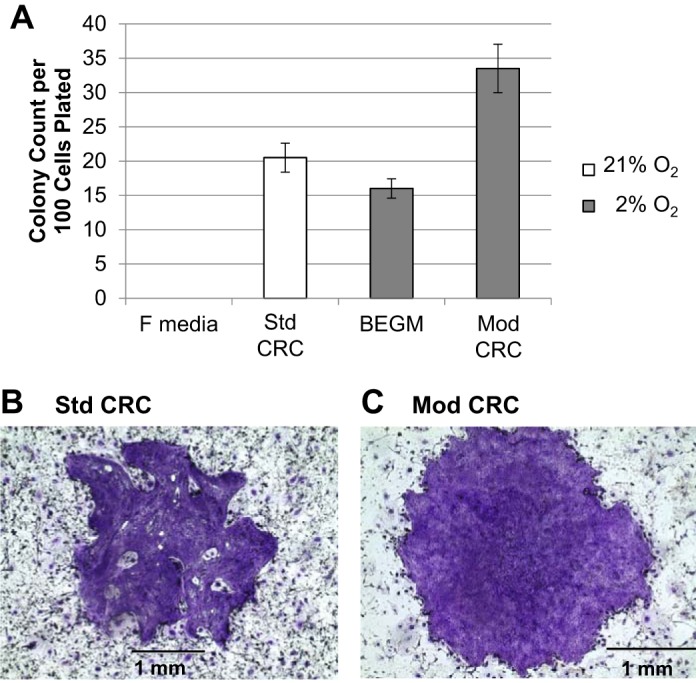

Human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) from a non-CF donor (NHBEC1) seeded at clonal density require Y-27632 (Y), irradiated 3T3 fibroblasts (IR3T3), and 2% O2 (Mod CRC conditions) to form the largest and most numerous clones with normal epithelial morphology. A: HBECs from donor NHBEC1 at 20 population doublings (PDs) in modified (Mod) CRC conditions were seeded at clonal density in 10-cm dishes in the 8 different HBEC growth conditions and allowed to grow for 10 days before fixation and staining with crystal violet. Representative dishes were imaged. BEGM, bronchial epithelial cell growth medium. B: average colony counts of 3 dishes for each of the conditions in A. Values are means ± SD. C–F: representative crystal violet-stained colonies for BEGM and BEGM + Y + IR 3T3 conditions with 21% or 2% O2. G: multichannel fluorescence confocal microscopy of a HBEC clone from donor NHBEC1 under Mod CRC conditions differentiated at the air-liquid interface and immunostained for mucin 5B (Muc5B)-expressing goblet cells (red) or acetylated α-tubulin (αtub)-expressing ciliated cells (green).

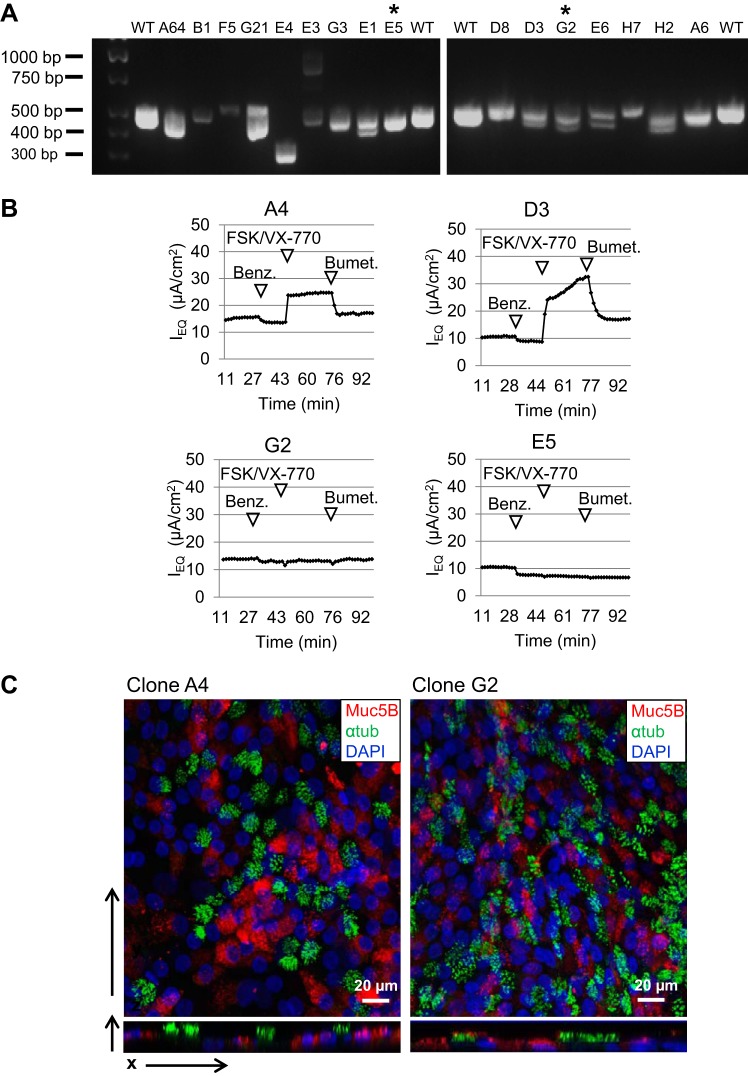

Fig. 9.

Modified conditionally reprogrammed cell (CRC) conditions enable efficient cloning and editing of CFTR by CRISPR/Cas9 in primary human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) from a non-CF donor (NHBEC1). A: for each of 16 clones, the region of CFTR exon 11 surrounding the CRISPR/Cas9 cut site was PCR-amplified from genomic DNA and separated by electrophoresis on two 2% gels, along with PCR product of genomic DNA from unedited HBECs with wild-type (WT) CFTR. *Clones G2 and E5 were selected for sequencing and further characterization. B: representative traces of 6–9 replicates from TECC-24 assay showed CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion in clones A4 and D3, but not in clones G2 and E5. Ieq, equivalent current; FSK, forskolin; Benz, benzamil; Bumet, bumetanide. C: multichannel fluorescence confocal microscopy shows that WT and mutant CFTR clones maintain the capacity to form a well-differentiated epithelium at the air-liquid interface, with abundant ciliated cells expressing acetylated α-tubulin (αtub, green) and goblet cells expressing mucin 5B (Muc5B, red).

Transepithelial Cl− secretion.

Transepithelial Cl− secretion was measured across monolayers of well-differentiated HBEC ALI cultures (4–5 wk) at various passages on HTS Transwell 24-well supports using a TECC-24 and a 24-well electrode manifold (EP Devices). CF HBECs were pretreated for 48 h with 3 µM VX-809 (lumacaftor; Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Boston, MA) or vehicle (DMSO; Sigma). TECC-24 analysis was carried out as described previously (30). Briefly, 24 filters were measured simultaneously under current-clamp conditions at 37°C while transepithelial voltage (Vt) and conductance (Gt) were measured continuously. The equivalent current (Ieq) was calculated using Ohm’s law, where Ieq = Vt·Gt. To prepare the 24-well plate for analysis, basolateral medium was aspirated and cultures were submerged apically and basally in assay medium [Ham’s F-12, pH 7.4 (Sigma), supplemented with 20 mM HEPES (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA)]. After an initial incubation of 45 min in assay medium in a CO2-free incubator at 37°C, each plate was moved to a prewarmed heating block at 36°C for electrophysiological measurements. Baseline Vt and Gt were measured for ~30 min; then Vt and Gt were measured continuously for 15 min after apical addition of benzamil (Sigma; 6 µM final concentration) to inhibit epithelial Na+ channel current, for 30 min after simultaneous apical/basolateral addition of forskolin (Sigma; 10 µM final concentration)/VX-770 (1 µM final concentration) to induce cAMP activation of CFTR/further potentiate CFTR, and for 15 min after basolateral addition of bumetanide (Sigma; 20 µM final concentration) to block Cl− secretion. Responses to reagents (benzamil/forskolin/VX-770 and bumetanide) were calculated as the change in Ieq before and after addition of the reagent. The peak/plateau response to forskolin was calculated; the plateau is the average Ieq starting from the time of forskolin/VX-770 addition and ending at the time of bumetanide addition. Values are means ± SE.

Indirect immunofluorescent staining.

Transwell supports (6 well) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde before the cells were blocked with immunofluorescence (IF) buffer, consisting of 7.7 mM NaN3, 0.1% BSA, 0.2% Triton X-100, and 0.05% Tween 20 (Sigma) diluted in PBS and containing 10% goat serum (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). Fixed cells were incubated with primary antibodies (1:50 dilution in blocking buffer) against mucin 5B (Muc5B; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and acetylated α-tubulin (Sigma) overnight at 4°C. The wells were washed three times with IF buffer, incubated with species-specific fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) for 1 h at room temperature, and washed three times with IF buffer. To counterstain nuclei, cells were incubated with DAPI (Thermo Fisher). Confocal images were obtained using an upright confocal microscope (model LSM 780, Zeiss).

Protein isolation and Western blot analysis.

Cell pellets were resuspended in RIPA lysis buffer, consisting of 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS; 100 µl per 1 × 106 cells. Protein (30 µg/sample) was separated on a 4–15% precast gel (Mini-Protean TGX, Bio-Rad) at 100 V for 1 h. Protein was transferred to a PFA membrane (Bio-Rad) using a Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer Pack (Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked with 5% milk for 1 h. All primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 1:1,000 dilution in 1% Tween 20 in PBS (PBST) at 4°C. The membrane was washed three times with PBST and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody raised against mouse or rabbit (Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was washed again three times with PBST and then imaged with a G:BOX (Syngene). The following primary antibodies were used: p63 (catalog no. sc-367333, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), keratin 5 (catalog no. ab24647, Abcam), p16 (catalog no. ab51243, Abcam), p21 (catalog no. ab109199), GAPDH (catalog no. 2118S, Cell Signaling Technology), and β-actin (catalog no. ab8227, Abcam).

Colony forming assays.

CRC or Mod CRC HBECs at 20 PDs were seeded at clonal density, 100 cells/50 cm2 dish, and two to three dishes per condition. Cells were seeded into Std HBEC CRC conditions [F medium + 5 µM Y-27632 + 5% FBS + 2.6 × 106 cryopreserved IR 3T3 fibroblasts + 21% O2] or in F medium + 5% FBS + 21% O2 as a control; cells were also seeded into Mod HBEC CRC conditions (BEGM + 10 µM Y-27632 + 10% FBS + 5 × 105 fresh IR 3T3 fibroblasts + 2% O2) or BEGM alone, BEGM + Y-27632, or BEGM + IR 3T3 fibroblasts in 2% O2 as controls. Cells were incubated in the respective conditions in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 10 days. On the final day, medium was aspirated and cells were fixed/stained with 6% glutaraldehyde/0.5% crystal violet (Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature with rocking. Dishes were rinsed with warm water until the water was clear, and the resulting clones in each condition were imaged, counted, and measured.

CRISPR/Cas9.

A single guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting exon 11 of wild-type CFTR at the site of the ΔF508 mutation, sequence ATTAAAGAAAATATCATCTT, was inserted into the pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP plasmid [PX458 (Addgene plasmid no. 48138), a gift from Feng Zhang] expressing Cas9 and GFP (22). CRC HBECs (15 PDs or passage 6) were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 1.1 × 105 cells/cm2 in BEGM + 5% FBS + 10 µM Y-27632 + 1 × 104 IR 3T3 fibroblasts/cm2 24 h before transfection with Transfex (Lonza) and 2 μg of PX458 plasmid with sgRNA insert. GFP+ HBECs (highest expressing 5%) were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting to 96-well plates 48 h posttransfection; each receiving well of a 96-well plate contained BEGM + 5% FBS + 10 µM Y-27632 + 1 × 103 IR 3T3 fibroblasts. Once clones reached confluence, they were expanded up to a 24-well plate and, finally, a 6-well plate (2.5 × 105–1 × 106 cells; 18–20 PDs from a single cell) from which the cells were cryopreserved or pelleted for DNA isolation. To test differentiation capacity and CFTR function on Transwell supports, clones of interest were thawed and expanded in 50-cm2 dishes, which produced ~3–5 × 106 cells (another ~3 PDs). Initially, 65 clones were collected for screening of genome editing (see PCR screen of CRISPR clones). Clones either homozygous for a CFTR mutation (indels) or wild-type for CFTR as a control were differentiated at the ALI on HTS Transwell 24-well permeable supports. ALI cultures resulting from genome-edited HBEC clones were analyzed for transepithelial Cl− secretion to determine if CFTR genotype correlated with CFTR function and were also analyzed by IF staining for cilia and goblet cells to evaluate morphology.

PCR screen of CRISPR clones.

Genomic DNA was isolated from HBEC CRISPR clones from non-CF donor NHBEC1 using a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A 500-bp region spanning the cut site of CFTR exon 11 was PCR-amplified using EmeraldAmp master mix (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) and 30 cycles with an annealing temperature of 63°C. The following primers were used to produce a ~500-bp PCR product from wild-type CFTR genomic DNA: 5′-AATCATGTGCCCCTTCTCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGGGTAGTGTGAAGGGTTCAT-3′ (reverse). Resulting PCR products were visualized by 2% gel electrophoresis for detectable insertions/deletions (indels). Candidate clones were further analyzed by TOPO TA cloning (Life Technologies) and Sanger sequencing to obtain allele-specific sequence information.

Data analysis.

A Student’s t-test was used to analyze significance. To test significance between passages in the same donor and condition, a paired t-test with a two-tailed distribution was used. To test significance between two different conditions in the same donor, a two-sample equal-variance t-test with a two-tailed distribution was used. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Graphs and statistics were generated with Microsoft Excel 2010 software.

RESULTS

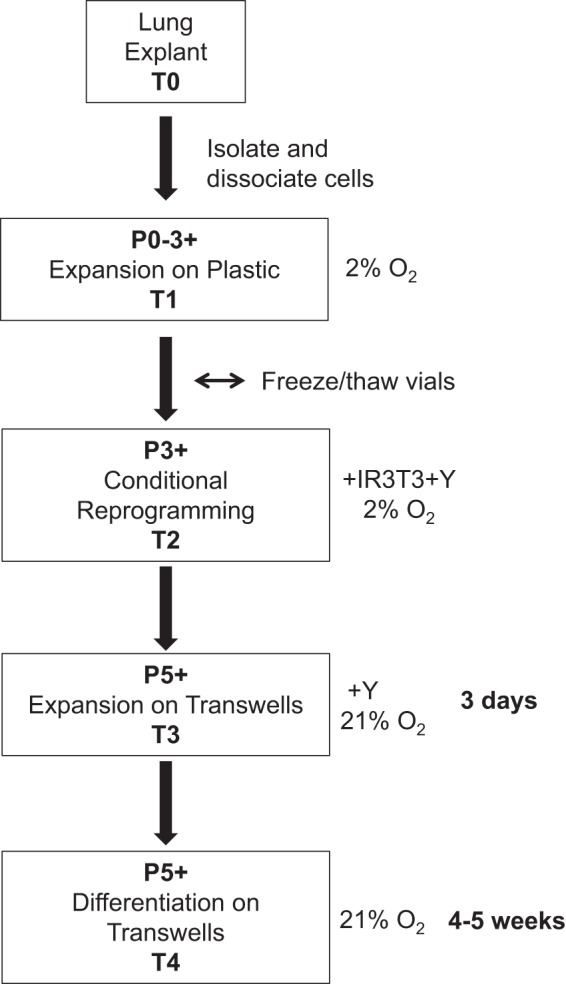

The procedures for growing and differentiating conditionally reprogrammed HBECs, including modifications of other protocols for conventional and CRC HBEC culture (9, 10), are summarized as a flowchart in Fig. 1. After isolation of primary HBECs from a lung explant, primary cells are expanded on plastic culture dishes in BEGM in 2% O2 (to reduce oxidative stress) for three passages before conditional reprogramming on a freshly IR 3T3 fibroblast feeder layer in the presence of 10 µM ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 and 2% O2 for ~10 passages (~20–30 PDs). Cell age in culture is more accurately calculated by PD than by passage number, which can differ from laboratory to laboratory based on the number of cells seeded per surface area and frequency of passage. However, most laboratories report passage number, so we report both PD and passage number to allow for comparison. For differentiation assays, CRC HBECs are seeded on collagen-coated Transwell supports for 3 days submerged in BEGM with 10 µM Y-27632 without a feeder layer in 21% atmospheric O2 before cultures are switched to the ALI. CRC HBEC ALI cultures are fed basally via the microporous membrane filter with differentiation medium without Y-27632 and IR 3T3 fibroblasts and are maintained in 21% O2 for 4–5 wk before end-point analysis. A comparison of the Mod CRC method with the conventional (Cnv) (9) and Std CRC (10) published methods is outlined in Table 1. There are several key differences between the Std and Mod CRC methods (underscored in Table 1), including O2 tension (21 vs. 2%), growth medium (F medium vs. BEGM), use of cryopreserved IR fibroblasts vs. freshly IR fibroblasts, and differentiation medium. Growth of normal human diploid cells in 2% O2 has been shown to significantly extend primary cell life span in culture and is attributed to decreased oxidative stress and reduced DNA damage (19). Low O2 tension has also been shown to control proliferation and maintain the undifferentiated state of a variety of stem cells, including induced pluripotent stem cells (18). Thus we tested the growth of HBECs in atmospheric 21 and 2% O2 in parallel.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of human bronchial epithelial cell isolation, expansion, conditional reprogramming, and differentiation. T, time; P, passage; IR 3T3, freshly irradiated (30 Gy) 3T3 fibroblasts; Y, Y-27632 (Rho-associated protein kinase inhibitor).

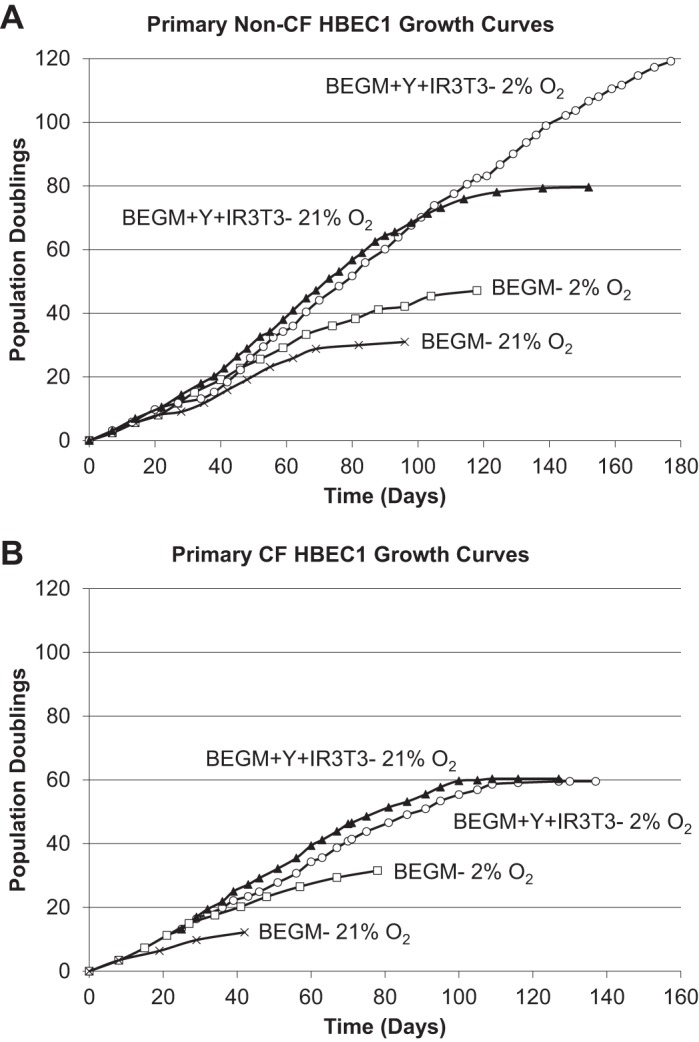

HBECs isolated from non-CF donor NHBEC1 and CF donor CFHBEC1 (see Table 2 for donor characteristics) were serially passaged in Cnv BEGM under 2 or 21% O2 as a control or Mod CRC conditions and 2 or 21% O2. Both primary cell strains senesced in Cnv conditions. The growth of primary HBECs from non-CF donor NHBEC1 in CRC conditions (BEGM + Y-27632 + IR 3T3 fibroblasts) was limited to 80 PDs in 21% O2, while 2% O2 significantly extended the life span of these HBECs beyond 100 PDs. However, the life span of HBECs from CF donor CFHBEC1 was limited to 60 PDs in CRC conditions in either 21 or 2% O2 (Fig. 2). Replicative senescence is defined as no cell proliferation in a 14-day period. Mod CRC conditions supported extended growth of primary HBECs that exceeded 25 PDs, ~10 passages, consistent with previous reports in Std CRC conditions (10). To compare differentiation capacities of primary HBECs cultured in Std CRC conditions with those of primary HBECs cultured in Mod CRC conditions, HBECs from donors NHBEC1 and CFHBEC1 were also serially passaged in Std CRC conditions and 21% O2 for 5-10 passages before differentiation at the ALI (Figs. 3 and 4). For a fair comparison, HBECs grown in Std or Mod CRC conditions were differentiated in the same differentiation medium, with the lower 0.01 mg/ml BPE concentration described for Std CRC conditions in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Growth curves of serially passaged human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) from a non-CF donor (NHBEC1) and a CF donor (CFHBEC1) in conventional bronchial epithelial growth medium (BEGM) and in modified conditionally reprogrammed (CRC) conditions with 21% atmospheric O2 or 2% O2. HBECs from non-CF (A) and CF (B) donors senesced after long-term culture in BEGM-21% O2 (×), and even in BEGM-2% O2 (□), while the same donors exhibited extended life span in CRC conditions with Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor Y-27632 (Y), irradiated 3T3 fibroblast feeder layer (IR 3T3), and 21% O2 (▲) or 2% O2 (○). Growth of primary HBECs from the non-CF donor in CRC conditions (BEGM + Y + IR 3T3) was limited to 80 population doublings (PDs) in 21% O2, while 2% O2 (BEGM + Y + IR 3T3-2% O2) significantly extended the life span of HBECs from the non-CF HBEC donor beyond 100 PDs. However, the life span of HBECs from the CF donor was limited to 60 PDs in CRC conditions with either 21% or 2% O2.

Although the same number of cells (1 × 105 cells/cm2) were seeded per Transwell support for each condition and all Transwell supports were 100% confluent before they were switched to the ALI, the number of cells per field was decreased by ~66% at passage 10 in ALI cultures of HBECs from donor NHBEC1 in Cnv + 2% O2 or Std CRC conditions (Fig. 3, B and D) compared with passage 5 cultures. Conditions with reduced number of cells correlated with reduced formation of ciliated (acetylated α-tubulin+) (23) and goblet (Muc5B+) (13) cells.

Passage 5 HBECs from donor NHBEC1 expanded in Cnv conditions under 2% O2 produced ALI cultures with ~30% ciliated cells and 14% goblet cells, which decreased to ~11% ciliated cells and 10% goblet cells in HBECs from donor NHBEC1 expanded in the same conditions for 10 passages. The decrease in ciliated cells from passage 5 to passage 10 in Cnv conditions was significant (P = 0.03). In comparison, Std CRC HBECs from donor NHBEC1 at passage 5 produced <5% ciliated cells at the ALI, and formation of cilia decreased to ~1% by passage 10, while goblet cell formation was maintained at 10–15% between passages 5 and 10. The 5% ciliated cells at passage 5 in Std CRC conditions was significantly less than the 30% ciliated cells at passage 5 in Cnv conditions (P = 0.02), and the decrease in ciliated cells from passage 5 to passage 10 in Std CRC conditions was significant (P = 0.04). Overall, Mod CRC HBECs from donor NHBEC1 produced the most ciliated cells at the ALI, with ~38% ciliated cells, which was maintained at ~33% ciliated cells at passage 10 (not significantly different). Mod CRC HBECs from donor NHBEC1 maintained the number of goblet cells produced at the ALI at 5–10% between passages 5 and 10 (not significantly different; Fig. 3, A–G). Maintenance of 33% ciliated cells in Mod CRC conditions at passage 10 was significantly higher than 11% ciliated cells at passage 10 in Cnv conditions (P = 0.01), and significantly more ciliated cells were produced under Mod CRC than Std CRC conditions at passages 5 and 10 (P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the number of goblet cells among conditions.

In the latest PD examined, PD 47 (passage 15), Mod CRC HBECs from donor NHBEC1 preserve the capacity to form a well-differentiated epithelium at the ALI with abundant ciliated and goblet cells (Fig. 3H). The capacity to differentiate into ciliated and goblet cells at PD 47, when HBECs in Cnv conditions have already senesced, allows for a significant expansion of the number of primary HBECs available for additional experimental investigations, including high-throughput screens.

HBECs from donor CFHBEC1 expanded in Mod CRC conditions maintained formation of ciliated cells at the ALI at 15–20% and goblet cells at 5–10% between passages 5 and 10 (not significantly different). Std CRC HBECs from donor CFHBEC1 at passage 5 produced <5% ciliated or goblet cells at the ALI and were absent by passage 10 (Fig. 4, A–E). Significantly more ciliated and goblet cells were produced at passages 5 and 10 in ALI cultures by HBECs from donor CFHBEC1 grown in Mod CRC than Std CRC conditions (P < 0.03). A decrease in ciliated cell formation as a function of passage for HBECs grown in Std CRC conditions was also reported previously (10).

To test if CFTR function was also maintained with differentiation capacity in Mod CRC HBEC ALI cultures, Cl− secretion was measured to determine CFTR channel function. CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion for ALI cultures of HBECs from donor CFHBEC1 in Cnv + 2% O2 vs. Std CRC vs. Mod CRC conditions was measured as Ieq using a TECC-24 (Fig. 5A). Since VX-809 has been shown to rescue function of ΔF508 CFTR in low-passage primary Cnv CF HBEC ALI cultures (29) and Std CRC HBEC ALI cultures (8), we tested the effect of VX-809 treatment in primary ALI cultures of HBECs from donor CFHBEC1 (ΔF508/ΔF508) previously expanded in Mod CRC conditions. Mod CRC HBECs from donor CFHBEC1 pretreated for 48 h with VX-809 showed rescue of forskolin (FSK) + VX-770-stimulated Ieq to 9.65 µA/cm2 at passage 5, which was significantly increased compared with control HBECs from donor CFHBEC1 in Cnv + 2% O2 conditions at passage 5, with an Ieq of 6.46 µA/cm2 (P < 0.00001). In contrast, Std CRC HBECs from donor CFHBEC1 pretreated with VX-809 showed rescue of FSK + VX-770-stimulated Ieq to 7 µA/cm2 at passage 5, which was not significantly different from control HBECS from donor CFHBEC1 in Cnv + 2% O2 conditions at passage 5. Passage 10 Mod CRC HBECS from donor CFHBEC1 exhibited a modest decrease of FSK + VX-770-stimulated Ieq to 7.38 µA/cm2, which was not significantly different from that of control HBECs from donor CFHBEC1 in Cnv + 2% O2 conditions at passage 5; in contrast, Std CRC HBECs from donor CFHBEC1 were not measurable by passage 10 because of loss of epithelial barrier/integrity (Fig. 5A). Changes in current magnitude as a function of passage were also previously reported for CF HBECs grown in Std CRC conditions (10). The level of rescue of ΔF508/ΔF508 CFTR Ieq in Mod CRC HBECs from donor CFHBEC1 is similar to that previously reported by Vertex Pharmaceuticals for low-passage primary CF HBECs grown in standard growth medium (29).

Since Mod CRC conditions maintained CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion, cells from two additional CF HBEC donors (CFHBEC2 and CFHBEC3) were grown in Mod CRC conditions for 10 passages before differentiation at the ALI for measurement of Cl− secretion using the TECC-24 assay. The average Ieq in response to FSK + VX-770 after pretreatment with VX-809 of all three CF HBEC donors grown in Mod CRC conditions was ~9 µA/cm2 at passage 5 and modestly decreased to 6 µA/cm2 at passage 10 (Fig. 5B). Cells from two additional non-CF HBEC donors (NHBEC2 and NHBEC3) were also grown in Mod CRC conditions for 10 passages before differentiation at the ALI for measurement of Cl− secretion using the TECC-24 assay. The average Ieq in response to FSK + VX-770 of all three non-CF HBEC donors grown in Mod CRC conditions was ~47 µA/cm2 at passage 5 and decreased to 37 µA/cm2 at passage 10 (Fig. 5C). Mod CRC conditions allowed for maintenance of CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion at passage 10, when HBECs grown in conventional conditions undergo senescence. The maintenance of CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion at passage 10 was reproducible among multiple HBEC donors.

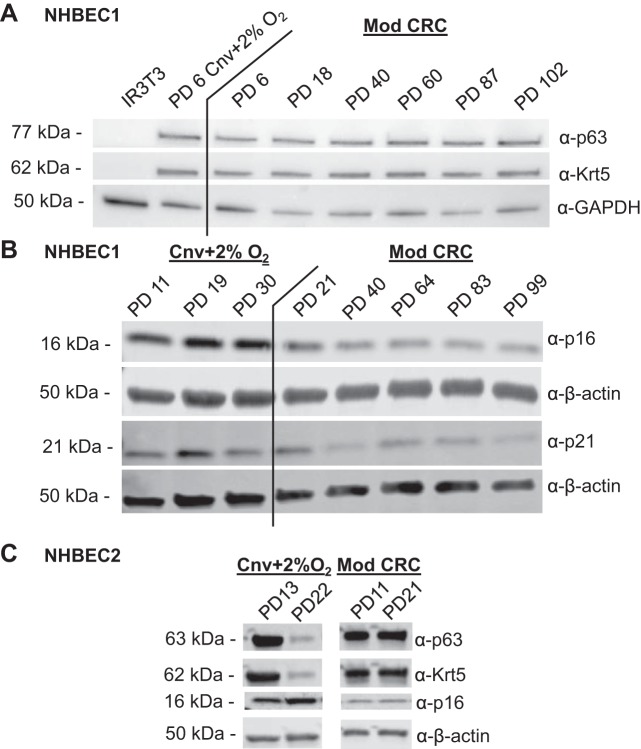

To characterize the multipotent and proliferative capacity of HBECs grown in Mod CRC conditions over time, HBEC basal progenitor marker expression and the senescence-associated markers p16 and p21 were evaluated by Western blotting. HBECs from donor NHBEC1 expanded in Mod CRC conditions maintained expression of the basal progenitor HBEC markers p63 and keratin 5 up to the latest PD examined, PD 102, with expression levels similar to low-passage PD 6 HBECs from donor NHBEC1 grown in Cnv conditions (and 2% O2) (Fig. 6A). Importantly, IR 3T3 fibroblasts do not express p63 and keratin 5, indicating that a population of primary HBECs, not fibroblasts, is being maintained on the feeder layer over time. In addition, expression of the senescence-associated markers p16 and p21 is high in HBECs from donor NHBEC1 grown in Cnv conditions (and 2% O2) for 30 PDs, while expression of these markers remains low in HBECs from donor NHBEC1 grown in Mod CRC conditions up to PD 99 (Fig. 6B). HBECs from a second non-CF HBEC donor, NHBEC2, also exhibited maintenance of basal progenitor markers p63 and keratin 5, while p16 was suppressed in Mod CRC conditions compared with Cnv conditions (and 2% O2) (Fig. 6C). Therefore, Mod CRC conditions reduce cellular stress in HBECs from non-CF donors and prevent premature cellular senescence in cell culture.

Fig. 6.

Expression of basal progenitor human bronchial epithelial cell (HBEC) markers is preserved at late passage, while senescence-associated proteins are suppressed in modified (Mod) conditionally reprogrammed cell (CRC) HBECs from a non-CF donor (NHBEC1). A and B: Western blot analysis of p63, keratin 5 (Krt5), and p16 or p21, as well as GAPDH and β-actin loading controls, for protein cell lysates from HBECs from donor NHBEC1 grown over time in conventional (Cnv) + 2% O2 or Mod CRC conditions. IR3T3, irradiated 3T3 fibroblasts. PD, population doubling. C: Western blot analysis of p63, keratin 5, and p16 for protein cell lysates from HBECs from donor NHBEC2 grown for 5 or 8 passages in Cnv + 2% O2 or Mod CRC conditions.

The multipotent and proliferative capacity of HBECs in Cnv, Std CRC, and Mod CRC conditions was further tested by colony formation assays. Since colony formation has been shown to be enhanced for human epidermal cells with more stem cell-like characteristics (25), we hypothesized that the colony formation assay would allow us to identify optimized growth conditions for primary human bronchial epithelial basal progenitor cells. HBECs from donor NHBEC1 were seeded at single-cell clonal density in 1) BEGM alone, 2) BEGM + Y-27632, 3) BEGM + IR 3T3 fibroblasts, or 4) BEGM + Y-27632 + IR 3T3 fibroblasts. The effect of 2% or 21% O2 tension on HBEC clonal growth was also tested for all cell culture conditions (Fig. 7A). Crystal violet staining and quantitation of the resulting colonies of HBECs from donor NHBEC1 demonstrated that BEGM alone and 2% or 21% O2 supported the growth of significantly fewer colonies of HBECs from donor NHBEC1 than BEGM + Y-27632 in 2% or 21% O2 and BEGM + Y-27632 + IR 3T3 fibroblasts in 2% and 21% O2 (P < 0.05). However, the colony number was significantly higher in BEGM + 2% O2 than BEGM + 21% O2 (P < 0.05; Fig. 7B), and colony size was also larger in BEGM + 2% O2 than BEGM + 21% O2 (Fig. 7, C and D). BEGM supplemented with both Y-27632 and IR 3T3 fibroblasts resulted in the most numerous colonies, with no significant difference between 2% and 21% O2 (Fig. 7B). In addition, colony size was similar between 2% and 21% O2 in CRC conditions (Fig. 7, E and F). BEGM + Y-27632 + IR 3T3 fibroblasts and 2% O2 (Mod CRC) significantly increased the number of colonies formed compared with the remaining conditions (P < 0.005); 21% O2 and BEGM + Y-27632 + IR 3T3 fibroblasts also supported an increased number of colonies compared with the remaining conditions (P < 0.05), except BEGM + Y-27632 and 21% O2. BEGM + IR 3T3 fibroblasts in 2% O2 significantly decreased the number of colonies formed compared with all other conditions, except BEGM + IR 3T3 fibroblasts in 21% O2 (P < 0.05), indicating that Y-27632 is a component critical to the enhanced growth of HBECs in CRC conditions.

In a direct comparison of the number of colonies formed by HBECs from donor NHBEC1 in Std CRC vs. Mod CRC conditions, we found that Mod CRC conditions supported growth of ~13% more colonies than Std CRC conditions (Fig. 8A). Mod CRC conditions also produced larger colonies with morphological characteristics similar to normal epithelial cells, in contrast to colonies grown in Std CRC conditions, which produced smaller colonies with irregular morphology (Fig. 8, B and C). Therefore, growth of primary HBECs at clonal density was best supported by Mod CRC culture conditions. Importantly, HBECs expanded from a single colony and, when placed in differentiation conditions at the ALI, produced both goblet and ciliated cells (Fig. 7G), demonstrating maintenance of multipotent differentiation capacity.

Fig. 8.

Modified (Mod) conditionally reprogrammed cell (CRC) conditions support enhanced colony growth of human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) from a non-CF donor (NHBEC1) compared with standard (Std) CRC conditions. HBECs from donor NHBEC1 at 20 population doublings (PDs) were seeded at clonal density in 10-cm dishes in Std CRC or Mod CRC conditions or in F medium + 5% FBS (F medium) or bronchial epithelial cell growth medium (BEGM) alone as controls. Colonies were grown for 10 days before fixation and staining with crystal violet. A: average colony counts for 2 dishes for each condition. No colonies grew in F medium control conditions. Values are means ± SD. B and C: representative crystal violet-stained colonies of HBECs from donor NHBEC1 in Std and Mod conditions.

Since it is necessary to clone cells after genome editing to identify clones with desired genetic changes, Mod CRC conditions were used to support CRISPR/Cas9 editing of the CFTR gene in primary HBECs. Low-passage HBECs from donor NHBEC1 were transfected with a plasmid coexpressing Cas9 and a sgRNA to introduce double-stranded breaks in wild-type CFTR exon 11 after the CTT nucleotides that are deleted in ΔF508/ΔF508 CF patients; double-stranded breaks repaired by error-prone NHEJ will likely result in knockout of the CFTR gene. Sixty-five CRISPR clones were successfully expanded in Mod CRC conditions and screened by PCR to identify any clones with indels large enough to produce a corresponding increase or decrease in PCR product size compared with wild-type on an agarose gel (Fig. 9A). Sixteen of 65 clones showed PCR products with shifts in size or double bands compared with wild-type, corresponding to a ∼25% efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in at least one allele. Since small indels cannot be identified with this PCR assay, it is possible that the CRISPR/Cas9 editing efficiency is higher than we observed. Two clones that exhibited a shift in PCR product size compared with wild-type, clones G2 and E5, were shown by Sanger sequencing to have deletion of 52 or 54 bp in one allele and deletion of 4 bp, CTTT, in the other allele and, thus, are effective CFTR knockouts. As controls, clones with bands similar in size to wild-type in an earlier screen (data not shown), clones A4 and D3, were also sequenced and confirmed to have wild-type CFTR sequence. Analysis of CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion by TECC-24 assay of the differentiated CRISPR clones demonstrated that CFTR function was maintained in clones A4 and D3, but not in clones G2 and E5 (Fig. 9B), corresponding to the wild-type and homozygous mutant CFTR genotypes of the isogenic clones. CFTR wild-type clone A4 and CFTR mutant clone G2 were each expanded from single cells sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting to one well of a 96-well plate and are, therefore, monoclonal but maintained multipotent differentiation capacity at the ALI (Fig. 9C). To our knowledge, this is the first time primary human bronchial basal cells have been cloned and demonstrated to maintain the multipotency of the heterogeneous parental cell population.

DISCUSSION

Primary HBECs are more representative of in vivo patient phenotypes than are immortalized or transformed lung epithelial cell lines. However, in current conventional culture conditions, primary HBECs have very limited proliferative and differentiation capacity in vitro. Recently developed CRCs support extended proliferation of healthy and diseased primary epithelial cells from multiple organ systems (15), including human nasal airway epithelial cells (24) and tracheobronchial epithelial cells from CF and non-CF airways (10). The published CRC methods demonstrate better preservation of CFTR function in well-differentiated cultures than Cnv conditions. However, CRC conditions do not preserve HBEC differentiation capacity to a well-differentiated epithelium with ciliated cells in ALI culture (10). In this report we directly compare a Mod CRC method with the Std CRC method (10, 15, 28) and show improved preservation of multipotent differentiation capacity (Figs. 3 and 4), in addition to maintenance of substantial CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion (Fig. 5), in late-passage HBECs. As outlined in Table 1, O2 tension and medium composition are two major differences between the Std CRC and Mod CRC methods, and a cloning assay demonstrated that 2% O2 and BEGM supported enhanced colony formation of HBECs compared with 21% O2 and F medium (Figs. 7 and 8). The colony formation assay also demonstrated that both Y-27632 and feeder layers are required for optimal growth of the largest and most numerous HBEC clones with normal epithelial morphology. This has also been demonstrated for heterogeneous populations of prostate epithelial cells (15), mammary epithelial cells (15), keratinocytes (20), and nasal airway epithelial cells (24).

The advantage of the direct comparison of the Std CRC with the Mod CRC method is that the same non-CF and CF HBEC donors were used. In contrast to a previous report, we could not measure a response to VX-809 at late passage in HBECs from our CF donor grown in Std CRC conditions because of loss of epithelial resistance. In the prior report, three CF donors exhibited a measurable response to VX-809 at late passage in the same conditions, although this response was significantly decreased compared with low-passage Std CRC cells (10). The inability to reproduce previous observations with Std CRC conditions for HBECs from donor CFHBEC1 could be attributed to donor variability and subtle differences in medium composition or passaging protocols between laboratories. However, for morphological and electrophysiological comparisons of Std CRC with Mod CRC conditions in Figs. 3, 4, and 5A, the cells were grown in the same differentiation medium described for the Std CRC condition (Table 1). Therefore, the differences between Std and Mod CRC conditions are due to differences in growth conditions, and not differentiation conditions. Overall, Std CRC (10) and Mod CRC (this report) conditions maintain substantial CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion at late passage, but Mod CRC conditions improve preservation of multipotent differentiation capacity compared with Std CRC conditions at late passage (this report).

As expected for primary cells from multiple donors, the magnitude of CFTR function was variable between HBECs grown in Mod CRC conditions. The three non-CF HBEC donors used in this study were also smokers, although donor NHBEC1 quit smoking ∼1 yr before cells were harvested. The three donors were also young: 19–21 yr old (Table 2). It is difficult to access primary non-CF HBECs from healthy donor tissue, as the cells are often harvested from the lungs of patients who have died from head trauma and are not suitable for transplantation because of, for example, smoking status. Mod CRC conditions should allow for the robust expansion of HBECs from healthy donor lungs, which would be more ideal controls for future studies of the downstream effects of mutated CFTR without the complication of the genetic or epigenetic effects of smoking.

While the detailed mechanism by which conditional reprogramming enhances long-term cell proliferation is not fully understood, in the present study we observed that p16/p21 senescence markers typically induced by cell culture stressors are greatly suppressed when HBECs are grown in Mod CRC conditions (Fig. 6). In addition, we observed that human bronchial basal cell markers are maintained in Mod CRC conditions (Fig. 6). Preservation of a stem cell-like phenotype has also been demonstrated for human ectocervical cells maintained in Std CRC conditions (28). Gene expression analyses of keratinocytes grown in Std CRC conditions showed a downregulation of differentiation genes and an upregulation of proliferation and cell adhesion (14), while similar gene expression analyses of nasal airway epithelial cells in Std CRC conditions showed altered expression of genes involved in cell cytoskeleton, cell-cell junctions, and cell-extracellular matrix interactions (24). ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 alone reduces apoptosis and increases cloning efficiency in dissociated human embryonic stem cells (31) and efficiently immortalizes human keratinocytes while maintaining normal karyotype, intact DNA damage response, and differentiation capacity (2). The IR fibroblast feeder layer is likely exhibiting a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (3) in response to extensive DNA damage from irradiation, which would result in secretion of a variety of cytokines, growth factors, proteases, and extracellular matrix proteins to promote cell survival and increase DNA damage repair. It has been shown that Y-27632 alone or feeder layer alone is not enough to extend the life of epithelial cells, but together the two components dramatically extend the life of a variety of epithelial cells (15). In our study, primary HBECs still senesced at 80 PDs in the presence of both Y-27632 and feeder layer in 21% O2, but HBECs grew beyond 100 PDs in Mod CRC conditions and 2% O2 (Fig. 2), suggesting that HBEC survival also requires low O2 tension to reduce reactive oxygen species and DNA damage and promote cell proliferation. This finding agrees with previous reports that low O2 tension is a critical component of the stem cell niche (18).

Primary HBECs grown in conventional culture conditions typically cease to grow by ~10 passages and have significantly decreased differentiation capacity and CFTR expression/function by passage 4 (33). However, primary HBECs grown in Mod CRC conditions exhibit a significantly extended life span that exponentially increases the number of cells available for experimental investigations, including drug screens. In this report we show that primary HBECs maintain differentiation and CFTR expression as late as 47 PDs, which increases the predicted number of cells from 210 to 247, a 109-fold potential increase. The ability to significantly expand primary HBECs allows for expansion of cells from small sample sizes, such as biopsies and brushings, which are less invasive than full organ explants and would allow collection of lung epithelial cells from truly healthy individuals, rather than explanted lungs from deceased patients with a history of smoking or patients with lung tumors. In addition, it will be easier to access lung epithelial cells from CF patients with rare and mild CFTR mutations and compare phenotypes of even-more-diseased and nondiseased primary lung epithelial cells in the future.

The conditional reprogramming scheme reported here also enables cloning of HBECs from single bronchial basal epithelial cells that maintain multipotent differentiation capacity at the ALI and express functional CFTR (Figs. 7 and 9). The Mod CRC conditions allowed for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing of CFTR exon 11, which introduced indels through NHEJ (Fig. 9). Therefore, it should be possible to introduce specific CFTR mutations through homology-directed repair, which will allow for creation of isogenic cell lines in which CFTR is mutant or wild-type in the same genetic background with no history or CF disease. Together, Mod CRC HBECs provide a valuable in vivo-like model system for study of the primary effects of mutant CFTR in primary non-CF HBECs that are not from a chronically inflamed and infected lung. Mod CRC HBECs will also enable study of rare CFTR mutations for which tissue is difficult or impossible to access.

GRANTS

This work was initially supported by National Cancer Institute Training Grant T32-CA-124334 and later by Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) Postdoctoral Fellowship PETERS15F0 (to J. R. Peters-Hall), Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas Training Grant RP140110 (to B. R. Alabi), a CFF Grant and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-49835 (to P. J. Thomas), and CFF Grant SHAY17GO to J. W. Shay. Confocal microscopy imaging was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant S10-RR-029731-01 (to Kate Luby-Phelps).

DISCLOSURES

P. J. Thomas is a paid advisor for the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and an equity holder and paid advisor for Reata Pharmaceuticals and ReCode Therapeutics. M. J. Torres is an equity holder for ReCode Therapeutics.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.R.P.-H., M.L.C., M.J.T., P.J.T., and J.W.S. conceived and designed research; J.R.P.-H., M.L.C., M.J.T., R.L., B.R.A., S.S., and J.F.C.-M. performed experiments; J.R.P.-H., M.L.C., M.J.T., R.L., P.J.T., and J.W.S. analyzed data; J.R.P.-H., M.L.C., M.J.T., R.L., P.J.T., and J.W.S. interpreted results of experiments; J.R.P.-H., M.L.C., M.J.T., and R.L. prepared figures; J.R.P.-H. drafted manuscript; J.R.P.-H., M.L.C., M.J.T., R.L., B.R.A., P.J.T., and J.W.S. edited and revised manuscript; J.R.P.-H., M.L.C., M.J.T., R.L., B.R.A., P.J.T., and J.W.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Raksha Jain and Ashley Keller for establishing a UTSW IRB protocol and getting patient consent. We are also grateful to the UTSW Adult CF team, transplant team, and the CF patients who participated in the study. We thank Scott H. Randell and Leslie Fulcher (University of North Carolina) for the generous gifts of primary CF and non-CF HBECs, Robert J. Bridges for expertise/training with TECC-24 analysis, Jaewon Min for help with design of the PX458 Cas9/sgRNA expression plasmid, Kimberly Batten for statistical advice, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Live Cell Imaging Facility for use of the Zeiss LSM 780 upright confocal microscope, Erik Welf and Abhijit Bughde for assistance with confocal microscopy, and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Children’s Research Institute Flow Cytometry Facility for assistance with cell sorting.

Present address for M. J. Torres: ReCode Therapeutics, 6001 Forest Park Rd., Dallas, TX 75235.

APPENDIX

HBEC Coculture with IR 3T3 Fibroblasts and ROCK Inhibitor

Materials.

-

•

Primary HBECs from biopsy, brushing, transplant, autopsy, etc.

-

•

Mouse Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts, J2 strain

-

•

Y-27632 ROCK inhibitor (10 mM stock in H2O at −20°C)

-

•

HBEC growth medium: 1:1 BEGM (catalog no. CC-3171, Lonza) and DMEM-high glucose with l-glutamine and sodium pyruvate (catalog no. SH30243.02, Fisher Scientific)

-

•

3T3 fibroblast growth medium: DMEM + 10% FBS

-

•

FBS

-

•

PBS

-

•

0.02% EDTA (0.68 mM) in PBS

-

•

0.05% trypsin for 3T3 fibroblasts

-

•

Trypsin-EDTA solution (TE; catalog no. R-001-100, Life Technologies) and trypsin neutralizer solution (TN; catalog no. R-002-100, Life Technologies) for HBECs

Propagation of HBECs with IR 3T3 Fibroblasts and ROCK Inhibitor

HBECs are propagated with IR 3T3 fibroblasts and ROCK inhibitor as follows.

1) 3T3 fibroblasts are proliferated in DMEM + 10% FBS and routinely passaged every 3–4 days at 0.5–1 × 105 cells per T25 flask.

2) When almost confluent, 3T3 fibroblasts are passaged to continue propagation or irradiated at 3,000 rad (30 Gy).

3) IR 3T3 fibroblasts are then trypsinized with 1 ml of 0.05% trypsin per flask at room temperature for a few minutes, neutralized with 2 ml of DMEM + 10% FBS, and pelleted before resuspension in 5 ml of HBEC growth medium for counting.

4) 5 × 105 IR 3T3 fibroblasts are seeded with 5 × 105 HBECs per 10-cm dish in a total of 10 ml of HBEC growth medium + 5% FBS + 10 μM Y-27632. Frozen 10-μl aliquots of Y-27632 are thawed immediately before 1:1,000 dilution in growth medium. Cultures are incubated in 2% O2 at 37°C for 3–7 days until 70–90% confluent without medium changes between passages. If medium pH decreases before cells are confluent, half of the medium can be replaced with growth medium + 10 μM Y-27632.

Notes.

-

•

3T3 fibroblasts are always freshly irradiated before use.

-

•

5% serum is necessary for 3T3 fibroblast attachment to the dish.

-

•

If the starting number of HBECs is <5 × 105, a smaller surface area can be used and the number of IR 3T3 fibroblasts can be decreased accordingly. Initially, HBEC proliferation rate will be slower, only requiring passage every 5–7 days. After a few passages, HBEC proliferation rate will increase, requiring passage every 3–4 days. If HBECs are to be passaged again in 3 days, the number of HBECs should be increased to 1 × 106, but the number of IR 3T3 fibroblasts should be maintained at 5 × 105 per 10-cm dish.

-

•

The order in which the cells are added to the dish is not important: either HBECs or IR 3T3 fibroblasts can be seeded first, seeded together, or seeded several hours apart.

Passaging HBEC-IR 3T3 fibroblast coculture.

5) When HBEC-IR 3T3 fibroblast cocultures are confluent, dishes are washed once with 10 ml of PBS and then with 3 ml of 0.02% EDTA in PBS for 5 min at 37°C to remove fibroblasts but retain HBECs. After 5 min, dishes are double-tapped 4 times at equidistant points around the perimeter of the dish to dislodge fibroblasts, and EDTA/detached fibroblasts are aspirated. Plates are washed again with 10 ml of PBS to remove residual fibroblasts.

6) HBECs are trypsinized with 2 ml of TE at 37°C for 10 min before 4 double taps to detach HBECs, neutralization with 2 ml of TN, and transfer of 4 ml of cell solution to a 15-ml tube. Plates are washed once more with 3 ml of PBS, and the “wash” is added to the 4 ml of cell solution before the solution is pelleted for downstream applications (e.g., proliferation, freezing).

REFERENCES

- 1.Boat TF, Welsh MJ, Beaudet AL. Cystic Fibrosis. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman S, Liu X, Meyers C, Schlegel R, McBride AA. Human keratinocytes are efficiently immortalized by a Rho kinase inhibitor. J Clin Invest 120: 2619–2626, 2010. doi: 10.1172/JCI42297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coppé JP, Desprez PY, Krtolica A, Campisi J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu Rev Pathol 5: 99–118, 2010. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crane AM, Kramer P, Bui JH, Chung WJ, Li XS, Gonzalez-Garay ML, Hawkins F, Liao W, Mora D, Choi S, Wang J, Sun HC, Paschon DE, Guschin DY, Gregory PD, Kotton DN, Holmes MC, Sorscher EJ, Davis BR. Targeted correction and restored function of the CFTR gene in cystic fibrosis induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Reports 4: 569–577, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.da Paula AC, Ramalho AS, Farinha CM, Cheung J, Maurisse R, Gruenert DC, Ousingsawat J, Kunzelmann K, Amaral MD. Characterization of novel airway submucosal gland cell models for cystic fibrosis studies. Cell Physiol Biochem 15: 251–262, 2005. doi: 10.1159/000087235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delgado O, Kaisani AA, Spinola M, Xie XJ, Batten KG, Minna JD, Wright WE, Shay JW. Multipotent capacity of immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells. PLoS One 6: e22023, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emerson J, Rosenfeld M, McNamara S, Ramsey B, Gibson RL. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other predictors of mortality and morbidity in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 34: 91–100, 2002. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fulcher ML, Gabriel SE, Olsen JC, Tatreau JR, Gentzsch M, Livanos E, Saavedra MT, Salmon P, Randell SH. Novel human bronchial epithelial cell lines for cystic fibrosis research. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296: L82–L91, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90314.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fulcher ML, Randell SH. Human nasal and tracheo-bronchial respiratory epithelial cell culture. Methods Mol Biol 945: 109–121, 2013. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-125-7_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gentzsch M, Boyles SE, Cheluvaraju C, Chaudhry IG, Quinney NL, Cho C, Dang H, Liu X, Schlegel R, Randell SH. Pharmacological rescue of conditionally reprogrammed cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 56: 568–574, 2017. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0276MA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson RL, Burns JL, Ramsey BW. Pathophysiology and management of pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168: 918–951, 2003. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-505SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gruenert DC, Willems M, Cassiman JJ, Frizzell RA. Established cell lines used in cystic fibrosis research. J Cyst Fibros 3, Suppl 2: 191–196, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2004.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmén JM, Karlsson NG, Abdullah LH, Randell SH, Sheehan JK, Hansson GC, Davis CW. Mucins and their O-glycans from human bronchial epithelial cell cultures. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 287: L824–L834, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00108.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ligaba SB, Khurana A, Graham G, Krawczyk E, Jablonski S, Petricoin EF, Glazer RI, Upadhyay G. Multifactorial analysis of conditional reprogramming of human keratinocytes. PLoS One 10: e0116755, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Ory V, Chapman S, Yuan H, Albanese C, Kallakury B, Timofeeva OA, Nealon C, Dakic A, Simic V, Haddad BR, Rhim JS, Dritschilo A, Riegel A, McBride A, Schlegel R. ROCK inhibitor and feeder cells induce the conditional reprogramming of epithelial cells. Am J Pathol 180: 599–607, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mali P, Esvelt KM, Church GM. Cas9 as a versatile tool for engineering biology. Nat Methods 10: 957–963, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ. CRISPR interference: RNA-directed adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea. Nat Rev Genet 11: 181–190, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nrg2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohyeldin A, Garzón-Muvdi T, Quiñones-Hinojosa A. Oxygen in stem cell biology: a critical component of the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell 7: 150–161, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Packer L, Fuehr K. Low oxygen concentration extends the lifespan of cultured human diploid cells. Nature 267: 423–425, 1977. doi: 10.1038/267423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palechor-Ceron N, Suprynowicz FA, Upadhyay G, Dakic A, Minas T, Simic V, Johnson M, Albanese C, Schlegel R, Liu X. Radiation induces diffusible feeder cell factor(s) that cooperate with ROCK inhibitor to conditionally reprogram and immortalize epithelial cells. Am J Pathol 183: 1862–1870, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramirez RD, Sheridan S, Girard L, Sato M, Kim Y, Pollack J, Peyton M, Zou Y, Kurie JM, Dimaio JM, Milchgrub S, Smith AL, Souza RF, Gilbey L, Zhang X, Gandia K, Vaughan MB, Wright WE, Gazdar AF, Shay JW, Minna JD. Immortalization of human bronchial epithelial cells in the absence of viral oncoproteins. Cancer Res 64: 9027–9034, 2004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc 8: 2281–2308, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rawlins EL, Ostrowski LE, Randell SH, Hogan BL. Lung development and repair: contribution of the ciliated lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 410–417, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610770104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds SD, Rios C, Wesolowska-Andersen A, Zhuang Y, Pinter M, Happoldt C, Hill CL, Lallier SW, Cosgrove GP, Solomon GM, Nichols DP, Seibold MA. Airway progenitor clone formation is enhanced by Y-27632-dependent changes in the transcriptome. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 55: 323–336, 2016. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0274MA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL,. et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science 245: 1066–1073, 1989. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwank G, Koo BK, Sasselli V, Dekkers JF, Heo I, Demircan T, Sasaki N, Boymans S, Cuppen E, van der Ent CK, Nieuwenhuis EE, Beekman JM, Clevers H. Functional repair of CFTR by CRISPR/Cas9 in intestinal stem cell organoids of cystic fibrosis patients. Cell Stem Cell 13: 653–658, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shay JW, Wright WE. The use of telomerized cells for tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol 18: 22–23, 2000. doi: 10.1038/71872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suprynowicz FA, Upadhyay G, Krawczyk E, Kramer SC, Hebert JD, Liu X, Yuan H, Cheluvaraju C, Clapp PW, Boucher RC Jr, Kamonjoh CM, Randell SH, Schlegel R. Conditionally reprogrammed cells represent a stem-like state of adult epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 20035–20040, 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213241109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, Burton B, Stack JH, Straley KS, Decker CJ, Miller M, McCartney J, Olson ER, Wine JJ, Frizzell RA, Ashlock M, Negulescu PA. Correction of the F508del-CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by the investigational drug VX-809. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 18843–18848, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105787108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vu CB, Bridges RJ, Pena-Rasgado C, Lacerda AE, Bordwell C, Sewell A, Nichols AJ, Chandran S, Lonkar P, Picarella D, Ting A, Wensley A, Yeager M, Liu F. Fatty acid cysteamine conjugates as novel and potent autophagy activators that enhance the correction of misfolded F508del-cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). J Med Chem 60: 458–473, 2017. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe K, Ueno M, Kamiya D, Nishiyama A, Matsumura M, Wataya T, Takahashi JB, Nishikawa S, Nishikawa S, Muguruma K, Sasai Y. A ROCK inhibitor permits survival of dissociated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 25: 681–686, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nbt1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright WE, Shay JW. Inexpensive low-oxygen incubators. Nat Protoc 1: 2088–2090, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zabner J, Karp P, Seiler M, Phillips SL, Mitchell CJ, Saavedra M, Welsh M, Klingelhutz AJ. Development of cystic fibrosis and noncystic fibrosis airway cell lines. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 284: L844–L854, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00355.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]