Abstract

In this article, we draw on ecocultural theories of risk and resilience to examine qualitatively the experiences of U.S. citizen-children living with their undocumented Mexican parents. Of central importance is the fact that citizen-children’s daily lives are organized around the very real possibility that their undocumented parents could one day be detained and deported. Our purpose is to render visible the various ways in which citizen-children confront and navigate the possibilities—and realities—of parental deportation. We develop a framework to conceptualize the complex multidimensional, and often multidirectional, factors experienced by citizen-children vulnerable to or directly facing parental deportation. We situate youth well-being against a backdrop of multiple factors to understand how indirect and direct encounters with immigration enforcement, the mixed-status family niche, and access to resources shape differential child outcomes. In doing so, we offer insights into how different factors potentially contribute to resilience in the face of adversity.

Keywords: Children, citizenship, deportation, undocumented, well-being

An estimated 4.5 million U.S. citizen-children live in families in which one or both parents are undocumented (Pew Hispanic Research Center 2013). Researchers are just beginning to understand the ripple effects of immigration enforcement policies on immigrant families, and particularly on those families comprised of members with different authorization statuses, or mixed status families (Dreby 2013). Due to escalations in punitive measures that target undocumented individuals in the U.S. (Peutz and De Genova 2010), a growing number of citizen-children face the harsh realities associated with parental deportation: forced family separations, material deprivation, anxiety, and depression (Gonzales and Chavez 2012; Zayas 2015). Citizen-children living in Mexican immigrant families experience a disproportionate burden of risk as the sociopolitical practices aimed at policing migrant “illegality” increasingly target individuals of Mexican origin (Dreby 2012).

To date, research has highlighted the various ways in which immigration enforcement practices increase the likelihood that citizen-children will experience academic challenges, physical and mental health problems, and cognitive and developmental delays (Cavazos-Rehg et al. 2007; Kersey et al. 2007; Perreira and Ornelas 2011; Potochnik and Perreira 2010; Suarez-Orozco and Yoshikawa 2013; Yoshikawa 2011; Zayas and Bradlee 2015). Although this research has drawn much-needed attention to the multi-level risk profiles of citizen-children, the predominant focus on risk has led to generalized assumptions about the vulnerability of this population and overshadowed the evaluation of citizen-children’s strengths, agency, and capacity (Panter-Brick 2014). This speaks, in part, to the political nature of research on undocumented individuals and their families. Most research, for good reason, advocates for changes to current immigration laws because studies have been able to demonstrate the negative effects such laws have on citizen-children in immigrant families. However, research that focuses attention solely on issues of risk obscures the ways in which citizen-children actively navigate stressful situations. Attention to processes of resilience would offer a valuable complement to the extant literature.

In this article, we draw on ecocultural theories of risk and resilience (Unger et al. 2013; Weisner 2007) to examine qualitatively the experiences of citizen-children living with their undocumented Mexican parents. We focus attention on how citizen-children cope within the context of current immigration enforcement and deportation policies. In doing so, we identify factors that shape the well-being of citizen-children and highlight the contextual circumstances that have the potential to produce variable individual outcomes. Our paper is framed to address the following research questions: What are the effects of immigration enforcement on the well-being of citizen-children? How do citizen-children cope with the fears associated with having an undocumented parent? What strengths do citizen-children draw on as they face the realities—and consequences—of parental deportation?

An Ecocultural Perspective on Resilience in Mixed-Status Families

Over the past decade, social scientists have turned their attention to resilience-based research to counter the dominant focus on vulnerability, victimization, and suffering. Whereas studies of risk attend to circumstances and behaviors that increase the likelihood of negative outcomes, resiliency approaches emphasize elements and processes that sustain or promote well-being. As noted by anthropologist Catherine Panter-Brick (2013, 163), studies of resilience “uncover how people manage to live their lives and make the best of dire circumstances.” In doing so, resiliency-oriented research can identify crucial “leverage points” that facilitate successful coping and shape well-being.

Studies of resilience draw on a range of theoretical approaches that emphasize, to different degrees, the salience of individual factors and the broader context. Many social scientists consider Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model (1979) to be foundational for understanding how interactions between individuals and their contextual environment shape childhood development (Ungar et al. 2013). Bronfenbrenner posited that proximal processes—those direct interactions between children and their immediate social and material environments (micro-level)—were the basic elements shaping development (Bronfenbrenner and Morris 1998). Broader ecological systems, such as the mesosystem (interaction between microsystems) and macrosystem (broader cultural and structural context) were understood as both shaping and being shaped by interactions in the microsystems (Bronfenbrenner 1993). In this way, change within one system could reverberate across systems.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological approach has influenced studies of risk and resilience by focusing attention to micro-, meso-, and macro-level factors that inhibit or facilitate well-being (Ungar et al. 2013). Building on Bronfenbrenner’s model, anthropologists and sociologists have reconceptualized the role of culture within his eco-developmental framework, critiquing the distal role that he presumed culture to play in the lives of children and their families. As sociologist Jonathan Tudge (2008) argues, “what is missing is that there is no sense … that cultural groups with values, beliefs, lifestyles, and patterns of social interchange different from those found in North American middle-class communities would necessarily value different types of proximal processes” (72–73). Eco-developmental approaches have drawn little attention to the significant ways in which cultural processes directly shape childhood experiences and outcomes. Such a limitation is particularly relevant for studies of citizen-children, whose experiences are invariably affected by macro-level contexts that mandate discrepant treatment and access to resources based on ethnicity and citizenship status.

In light of this, our paper adopts an ecocultural approach that prioritizes attention to culture, or the everyday activities, routines, and behaviors that children enact within their surrounding environment (Super and Harkness 1986; Trudge 2008; Weisner 2007; Worthman 2010). Ecocultural theory emphasizes the importance of family practices and strategies that families pursue in order to facilitate child development and well-being (Weisner 2002). As noted by anthropologist Thomas Weisner, families everywhere need to construct and sustain family practices that foster survival, create meaning, and ensure positive outcomes for their children (Weisner 2010). Yet, not all family practices are equally effective or achievable. Even though practices are actively constructed by families, they are also influenced by features in the surrounding environment. These include material and institutional resources, health and safety characteristics of the home and community environment, expectations about the division of household and economic labor, informal and formal systems of support, and sources of cultural influence. Accordingly, family practices reflect a negotiation between opportunities and constraints in the surrounding environment and the cultural scripts that families draw upon to organize and give meaning to everyday life and promote childhood well-being. The nexus of culture, environmental factors, and everyday family life is constituted in the family niche (Weisner 2002, 2007). We extend an ecocultural conceptualization of the family niche to highlight the unique circumstances facing mixed-status families. A mixed-status family niche reflects the micro-environment created by families as they balance the needs of the family alongside the daily challenges associated with having a family member who is undocumented.

Crucial to understanding the mixed-status family niche is what we call a “cultural script of silence.” As Genevieve Negrón-Gonzales (2014, 271) notes, “silence is a fundamental part of the undocumented experience in this country … [because] the potential consequences of discovery are so severe.” Drawing on the notion of a cultural script of silence, we analyze the ways in which citizen-children interpret, manage, and navigate everyday life. Citizen-children’s daily lives are organized around the very real possibility that their undocumented parents could one day be detained and deported. In this context, developmental tasks take on new meaning when a knock on the family’s door has the potential to signal a shift in the safety and integrity of the family and the beginning of a terrifying ordeal of parental detention and deportation. Our purpose is to render visible the various ways in which citizen-children confront and navigate the possibilities—and realities—of parental deportation, in order to identify factors that potentially contribute to resilience in the face of adversity. In doing so, we highlight those factors that potentially distinguish citizen-children from their peers in citizen families.

Methods

Data analyzed for this article were drawn from a mixed-method, multi-sited binational study that examined the psychosocial functioning of citizen-children with undocumented Mexican parents. Study sites included Austin, TX; Sacramento, CA; and several locations throughout Mexico (Distrito Federal, Hidalgo, Michoacán, Oaxaca, and Sinaloa). The sampling strategy entailed recruitment of three different groups of U.S. citizen-children between the ages of 8 and 14 years with at least one undocumented Mexican parent: (1) citizen-children who had accompanied their parents to Mexico following parental deportation; (2) citizen-children who stayed in the U.S. with a parent or guardian after one or both parents underwent deportation proceedings, had been deported to Mexico, or returned to the U.S. following deportation to Mexico; and (3) citizen-children whose undocumented parents had never been detained by immigration enforcement. Participants were excluded for participation if they did not fall within the targeted age range or were living in foster care or child welfare at the time of the study. Additional exclusionary criteria included a diagnosis of psychiatric disorder or cognitive or developmental disability as these present unique challenges that might shape the well-being of citizen-children.

Recruitment was carried out with the help of staff at local community agencies at each site. After identifying potential participants who met criteria for participation, agency staff discussed the study with parents. Parents who expressed interest were referred to the research team. All parents and children provided consent and assent for their participation, and IRB approval was granted at each of the institutions and sites where research activities took place.

Participants

Table 1 illustrates the demographic characteristics of citizen-children recruited for participation. Of the total 83 participants, 31 accompanied their parent(s) to Mexico following parental deportation, 18 remained in the U.S. after parental deportation, and 34 participants were not directly affected by parental deportation at the time of the interview. Across participant sub-groups, the majority of participants were girls (60.2 percent). Nearly all participants were enrolled in school and living with both parents at the time interview.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Citizen-Children in Study Sample

| Demographic Characteristic |

Accompanied Parent to Mexico after Parental Deportation (n=31) |

Remained in the U.S. after Parental Deportation (n=18) |

Living in the U.S. with an UndocumentedParent (n=34) |

Total (n=83) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) |

n (percent) |

M (SD) |

n (percent) |

M (SD) |

n (percent) |

M (SD) |

n (percent) |

|

| Age | 11.1 (1.9) | 11.7 (1.8) | 11.6 (1.9) | 11.4 (1.9) | ||||

| Gender (girl) | 19 (61.3) | 11 (61.1) | 20 (58.8) | 50 (60.2) | ||||

| School enrollment (yes) | 30 (96.8) | 18 (100) | 34 (100) | 82 (98.8) | ||||

| Living arrangement | ||||||||

| Both parents | 20 (64.5) | 10 (55.6) | 26 (76.5) | 56 (67.5) | ||||

| One parent | 10 (32.3) | 8 (44.4) | 7 (20.6) | 25 (30.1) | ||||

| No parent | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (2.4) | ||||

Data Collection

In-depth interviews were conducted with citizen-children to elicit their narratives about living with parents who were undocumented, and when applicable, to gather detailed accounts of their perceptions and experiences with immigration enforcement and parental deportation. All interviewers were bilingual, and the majority were Mexican or Mexican-American women pursuing graduate degrees in the social sciences and trained to conduct qualitative interviews with children. Each interviewer conducted the interview in the language preferred by the participant, and approximately 42 percent of the interviews were in Spanish.

To help reduce interviewer bias across multiple research sites, the research team constructed a semi-structured interview guide to provide a series of probes and prompts to facilitate deeper exploration of topics. Questions were open-ended in order to capture how citizen-children communicated, gave meaning to, and constructed their experiences and perceptions (Ochs and Capps 1996). The interview was conducted in a way that simulated a casual and everyday conversation, and interviewers encouraged children to ask questions and provide feedback about the interview process in order to facilitate rapport. Interviews began with a “grand tour” question (Spradley 1979) to explore participants’ perceptions about home and family life, including descriptions of family activities and relationships, the child’s roles and responsibilities within the family, and social life outside the home. These questions set the stage for a discussion about direct and indirect experiences with immigration enforcement and/or parental deportation. Interviewers focused on eliciting what the child remembered as meaningful, placing particular emphasis on having children describe their perceptions, thoughts, emotions, feelings, reflections, and interpretations to ascertain the psychosocial impact of parental removal or having an undocumented parent. If applicable, children were asked to reflect on how their life had changed as a result of the deportation process.

Throughout qualitative data collection, several procedures were followed to monitor and enhance the data quality. All interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and analyzed in the language of the interview to enhance validity (Guest and MacQueen 2008). Interview transcripts and notes were systematically reviewed, and a series of debriefing meetings took place with research team members to discuss the rigors of the data collection process (Mack et al. 2008).

Data Analysis

Transcripts were analyzed using a thematic approach to identify and describe participants’ perspectives (Guest et al. 2012). To develop the coding framework, the first author and a graduate research assistant independently read two interviews, recording their initial interpretations of text. Emergent themes were discussed in a team meeting, and a draft of a codebook was developed from this discussion. Additional interviews were read to test the utility of preliminary themes, with attention directed toward the emergence of new themes. After eight interviews had been read, themes in the codebook appeared to be well established, and a final draft of the codebook was produced. To test the utility of the codebook and establish intercoder reliability, four interviews were uploaded into NVivo9, independently coded by the first author and the research assistant, and percent agreement was calculated using the coding comparison module. Text that fell below a 75 percent threshold (Miles and Huberman 1994) was discussed during a team meeting, and the codebook was revised as necessary. Interviews were subsequently coded using NVivo9, first by the research assistant, and then by the first author. This approach facilitated the transparency of the coders’ interpretations of the data by reviewing and monitoring all coded text.

After the completion of data coding, a framework matrix was generated in NVivo9. A framework matrix organizes data by themes (columns) and participants (rows). Each cell of the matrix contained reduced data in the form of direct quotes and summarized information about the manifestation of a given theme in a particular case. The matrix was then exported and converted to a text document that contained the reduced and summarized information pertaining to each specific participant, or case.

To protect against bias in the interpretation of the cases, a panel of 13 experts reviewed the data to compare the experiences of citizen-children across cognitive, emotional, psychological, cultural, and socioeconomic dimensions. The panel included clinical psychologists and social workers in Mexico and the United States, and each had expertise in the mental health and cultural issues experienced by Latino youth and their families. Each panelist evaluated a random selection of 20 cases to ensure that each case was reviewed by multiple panelists. The panelists were brought together to discuss the results of their analysis.1 Their discussions were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed to develop a list of all of the issues faced by citizen-children and the contextual factors that exacerbated or ameliorated citizen-children’s direct and indirect experiences with immigration enforcement. The list originally contained 339 items, which the first author organized into 61 categories. Each category was subsequently linked to the interview data by annotating which cases corresponded to a given category. The arrangement of items and specification of categories was then reviewed and discussed by the research team and revised accordingly. As the list of categories was finalized by consensus, a framework was developed to capture the differential effects of immigration enforcement on the well-being of citizen-children. The framework was revised and finalized through an iterative team process (see Sobo 2009).

Results

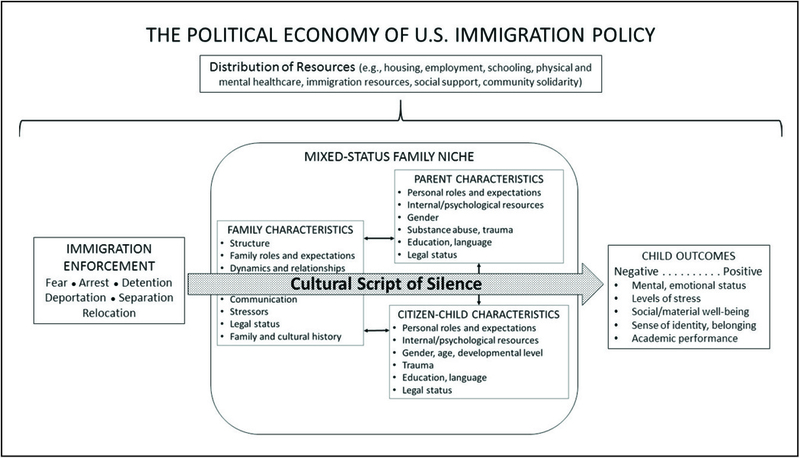

In Figure 1, we offer a framework to describe the varied circumstances facing citizen-children to conceptualize the range of effects immigration policies have upon the well-being of U.S. citizen-children. Figure 1 illustrates the interrelationships among five categories that emerged as salient to the perspectives of citizen-children: (1) immigration enforcement; (2) the cultural script of silence; (3) the distribution of resources; (4) the mixed-status family niche; and (5) child outcomes. Variations in child outcomes, as experienced and narrated by citizen-children, depended strongly on the particular processes and characteristics in place within specific contexts. Below, we begin with a description of the script of silence, followed by an exploration of the ways in which citizen-children drew on the cultural script of silence to navigate the various personal, social, and material ecologies that characterized their lives in their efforts cope with and adapt to situations beyond their control. To contextualize the framework, we present accounts of U.S. citizen-children, in their own words. All names used below are pseudonyms.

Figure 1.

Framework for Understanding the Effects of Immigration Enforcement on Citizen-Child Outcomes

The Cultural Script of Silence

As illustrated in Figure 1, the cultural script of silence emerges within a specific context: the enforcement of U.S. immigration policies. With the potential for an act of immigration enforcement to rupture family ties, most children perceived encounters with immigration enforcement as the worst event that could befall a family. Encounters could be indirect, through the potential threat of parental deportation or knowing others who had been deported; or direct, through the arrest, detention, and/or deportation of a parent. The condition of illegality, which rendered a parent’s deportation possible, created and maintained a context ripe for the development of a cultural script of silence. Nearly every citizen-child in our study described the salience of silence within their families. We call this phenomenon “the cultural script of silence,” referencing a shared script, or code, held among family members that prohibited the discussion of legal status both within and outside of the household. The script of silence shaped parents’ interactions with their own children and what they told their children about immigration, citizenship, and undocumented status. Not only did the script guide the ways in which parents and children interacted, but it also informed how parents taught or modeled behaviors, and the ways in which parents communicated and provided support.

The importance of silence was first learned indirectly. As 15 year-old Tommy, whose father had been detained, explained, “I guess it wasn’t really that I found out [about my parents’ status]. It was more like, like an idea you settle into, and that you think is normal. And like all the fears they have, you start to have, too.” Like Tommy, most participants in our sample stated that their parents rarely discussed the realities associated with being undocumented, although many children referenced an embodied comprehension of their parents’ undocumented status as a result of the various ways in which illegality organized dynamics within the mixed-status family. Children only came to know definitively about their parents’ status through the occurrence of a specific event that forced parents to voice their status to their children. For example, when one participant, Marianela, was eight years old, she learned that both her parents were undocumented when her father became severely ill. As she recalled the moment, “I told my mom that we should take him to the hospital to see what is going on with him … And that’s when my mom told me that we can’t take him to the hospital. And that’s when I said, ‘He’s sick. We need to take him to the hospital.’ And my mom told me that my dad didn’t have any papers.”

Once citizen-children learned that their parents were undocumented, they became keenly aware of the ways in which a cultural script of silence delineated family expectations for children’s interactions outside of the home. For example, Tommy explained that his parents provided him with explicit instructions to monitor his behavior in public. As he shared, “Whenever we were around important people, you know like, those people who deport other people, I have to behave very well.”

In other families, citizen-children were strongly encouraged to remain silent about their parents’ undocumented status. As 9 year-old Catarina explained, “Because my mom doesn’t want me to tell anyone she says that she could get in trouble if I talk to people about it.” To be sure, participants were aware of the pragmatic necessity for silence to protect their parents from detection by immigration enforcement agencies. For example, 14 year-old Jessica recounted a time when her friend’s mother had been deported after being reported to legal authorities: “It happened to my friend. That’s the only reason why her mom went to Mexico. Because her neighbors snitched them out that her mom didn’t have papers. I worry if I tell someone, the same thing is gonna happen as it happened to her.” Despite the pragmatic need for discretion, the script of silence contributed to experiences of powerlessness among citizen-children. As Tommy explained, “we can’t really say our mind or protest because we might get taken. We have to, like, stay to the laws a lot more than other people. Because they’ll judge us on our skin and say, ‘Oh, you’re Mexican. Go to your side.’”

In its most extreme manifestation, the cultural script of silence could set into motion a series of emotional or family dynamics that negatively affected the well-being of citizen-children. The cultural script of silence shaped children’s cognitive and emotional expression, and some participants described conscious efforts to “not think” about their parents’ situation. Maya, 9 years old, described, “I really don’t think about that. I just think fun things.” For many participants, the potential for a direct encounter with law enforcement produced considerable fear, worry, and stress. For example, Maria, a 10 year old who lived with her undocumented parents and younger citizen-brother, explained, “I have papers, and they don’t. They can’t really go places. They could go to prison.” This awareness led to extreme fear of police officers. When Maria saw a police car near her house, she would run inside, close the curtains, and cry profusely. It was not until the police left the vicinity that Maria would realize her parents were safe, and only then would she come out of hiding. Her fear of law enforcement stemmed from the very real possibility that “maybe one day, they can just take them. And then, me and my little brother would have to go to foster homes. I really don’t want that.”

Deliberate efforts to silence thoughts and emotions prevented children from having a space, either with family or friends, to process their fears, anxieties, and worries. The importance of silence within families sometimes acted to weaken supportive bonds between parents and children, and participants reported becoming distrustful of their parents as a result. As 11-year old Anthony noted, “They’re lying and all that. Like they knew they did not have papers, but they didn’t tell me.”

Surprisingly, silence often continued even after families experienced the worst possible circumstance: the arrest, detention, and deportation of a parent. Of those children who experienced parental detention or deportation, they explained that they knew very little about the immigration proceedings that led to the deportation of their parents. For example, Anthony did not understand why his father “went” to Mexico. Although his father had been deported eight months prior to the interview, he reported that he knew “only that my dad was going to Mexico. [My mom] didn’t want to talk about it.” Similarly, for 11-year-old Ernesto, the events resulting in his father’s deportation were unclear. Ernesto explained that he woke up one day to learn that his father had been “taken” to Mexico. As he described, “I just woke up and asked mom what happened. And she said they took him back to Mexico. He was somewhere, and they sent him to Mexico. I think he did something bad … I don’t know.”

Some participants could vividly recall the circumstances surrounding parental deportation because they witnessed directly the arrest and detention of their undocumented parent. For example, Christina was 12 years old when her mother was arrested. According to Christina, who was 14 at the time of the interview, ICE agents arrived at Christina’s house early one morning:

Like five in the morning. They just came … knocking on the door. And like, my mom, she was really scared. And my dad was like, ‘pack your stuff! And let’s leave.’ And [my mom] looked outside the window, and the house was surrounded. It was surrounded by like ICE people. And I heard, like, loud knocking. And like, I just got up […], and I was like, ‘what’s going on?’ Because there were, like, a lot of people on the porch. Everywhere. I was, like, super scared […]. And like, they took her. And she gave me the last hug, and um … She walked out of the door. And I was like, ‘You can’t leave us!’ (Christina’s voice cracks, and she starts to cry quietly.) So … me seeing my mom go away, it was very hard for me.

Christina recounted how she retreated into herself following her mother’s arrest. As she explained, “I quit my grades, and with, like, everything.” Christina’s eventual healing, described below, only occurred once she found a space to vocalize her experience. Still, when Christina reflected on that horrible night, she actively wished that she could erase, not only her mother’s arrest, but her presence during it: “If I could change anything in my life, I would probably change that. I would wish not to be there whenever they took my mom. I wish I would never see that.”

Importantly, not a single participant in our study described having a plan in place that would help guide and assist children about what to do in the event that a parent was arrested and detained. In this way, the cultural script of silence seemed to thwart the implementation of emergency plans for children and their families. As a result, participants described intense emotional experiences during the arrest and detention of a parent, and in turn, active efforts to mute the painful memories associated with such experiences. For example, 13-year old Guillermo, in describing the arrest and detention of his father, stated, “Like sometimes it comes to my mind, but mostly I don’t think about that. I don’t know. When I’m about to go to sleep, it just comes up.” The middle of the night, when he would wake from nightmares about his father, represented some of the bleakest times for Guillermo.

It is important to note that the cultural script of silence was not static or unchanging in its manifestation. The salience of the script, both in guiding family dynamics and the extent to which it affected the well-being of citizen-children, depended on the quality of resources available to children and their families. Although the script of silence operated as a kind of mediating force that shaped specific patterns of emotions, thoughts, behaviors, and dynamics within the mixed-status family, the well-being of citizen-children was more than the simple presence or absence of a cultural script. Rather, well-being was also shaped by the availability and distribution of and access to social and material resources.

Distribution of Resources

All of the participants in our study came to feel, experience, and understand the socio-political condition of illegality via their encounters with public institutions and broader community settings. Healthcare, employment, housing, neighborhood violence, and discrimination emerged as salient nodes around which citizen-children came to understand the meaning of their parents’ undocumented status, the political and economic constraints associated with lack of citizenship, and their own location within the constellation of discourses surrounding perceptions of individuals deemed illegal. The political and economic consequences of illegality reverberated across families of mixed-status through everyday lived experiences. Varied assemblages of legal statuses within and across families—citizen, authorized, undocumented—shaped the everyday experiences of citizen-children differently, and the distribution of resources was often the driving force behind these differential experiences. As Figure 1 illustrates, access to financial, education, extracurricular, mental health, legal, and immigration-related resources often translated to the differences between suffering, on the one hand, and resiliency, on the other.

In mixed-status families with one authorized or citizen-parent, citizen-children described less acute financial and housing struggles. In this way, legal status operated as a definitive resource. Nevertheless, the condition of illegality reverberated across the household even when only one parent was undocumented. In these cases, issues related to the institutional invisibility of the undocumented parent loomed large. For example, Cecilia, the 10-year old daughter of an undocumented mother and citizen-father, recounted that “the school doesn’t know my mom’s name. She can’t sign our paperwork, and they only see my dad.” Her mother’s undocumented status altered the domestic organization of responsibilities within the household, and her father was charged with acting as both mother and father in the public sphere.

Among citizen-children whose parents were detained, chronic experiences of political and economic marginalization sometimes shaped family decisions to accept deportation. In the case of Jennyfer, a 14-year old who lived with her undocumented grandmother and undocumented mother, her mother became gravely ill. Her mother had been diagnosed with Hepatitis C, which Jennyfer thought had been the result of a blood transfusion her mother received during childbirth. The family considered returning to Mexico to enable her mother to receive healthcare, but soon after this discussion, Jennyfer’s grandmother was arrested and detained. Given the status of the mother’s health, the grandmother accepted deportation so that the mother could receive the care she needed in Mexico. Although Jennyfer felt “sad” to leave the U.S., she noted, “I would prefer that we moved here so that my mother could get better rather than stay there and watch her get worse.” For Jennyfer and her family, barriers to accessing healthcare influenced the conditions under which they would “accept” deportation, and in the end, Jennifyer decided that she would do whatever it would take to stay close to her mother.

Among participants who relocated to Mexico to reunite with their deported parents, many described how they initially missed the conveniences and material abundance associated with life in the United States, such as shopping at big box stores. However, these experiences gave way to more profound sensations of loss about their potential futures and resources. As 12 year-old Clarissa explained, “If I stay here [in Mexico] I won’t have the chance to have any kind of future.” Participants described Mexico as a place with limited educational and employment opportunity. Twelve-year old Luciana narrated a particularly difficult adjustment to the school setting in Mexico. She described repeatedly asking for help in her studies, but her teachers did not respond to her requests. They would tell her they were “too bored” by her questions. As a result, she lost any desire to do well in school: “I see that my grades have dropped a lot because I’m like, why would I try if no matter what I do, the teachers aren’t even going to notice?’”

Cases such as these reveal the various ways in which access to resources might have contributed to different outcomes for children in our study. Although legal status excluded many families from accessing resources, such as safe employment and healthcare, key players within institutional and family settings figured prominently in facilitating participants’ access to what limited resources were available. For example, soon after the arrest and detention of Christina’s mother, described above, her father was detained and deported. Although her mother was eventually released, Christina and her siblings experienced major disruptions in terms of housing and access to material resources. Desolate, Christina broke the script of silence and reached out to her school counselor: “I told my counselor that we really needed help ‘cause, like, it was more than ten people living at my aunt’s house. And she didn’t have enough money for us. So [my counselor] got most of the teachers, they donated food and clothes. I remember coming home from school with a lot of bags full of like food and diapers and other stuff.” For Christina and members of her family, the school staff provided material resources needed to sustain family life. Moreover, the counselor created a supportive environment for Christina to process her emotional reactions to her father’s deportation.

For other citizen-children, extended kin emerged as key brokers to accessing resources. Karla, 12 years old, described the significance of extended kin in shaping her experience of reuniting with her family in Mexico following her father’s deportation. Her grandfather helped to ease the transition economically, and he provided Karla’s family with a house in Mexico and gave her father a job working in his painting business. On occasion, Karla’s grandfather would supplement the family’s income when they needed the extra money. With the additional money provided by her grandfather, Karla was able to maintain her involvement in sports, which helped to provide continuity between her former life in the U.S. and her new life in Mexico. Karla had participated in club boxing in the U.S., and through her grandfather’s support, she was able to join a boxing gym in Mexico. During the interview, Karla noted excitedly that she was anticipating her first boxing match. She had been training for “a long, long time. They put me up against a ninth grader, and I am barely in sixth grade. But she’s tiny! And I’ve been training for this … for the day that I’ll fight.”

The cases of Christina and Karla reveal how access to resources was shaped by relationships between citizen-children and other individuals within their social network. In this way, social support functioned as a critical resource, particularly when trusted family and friends constructed a space to dismantle the cultural script of silence. In the case of 14-year old Elena, for example, she described how she became withdrawn and uncommunicative upon learning that her father had been detained. In response, her mother reached out to her and enrolled her in dance class to provide an outlet for her “frustration.” In this way, Elena’s mother provided support by finding a space in which Elena could process her emotions. In addition to family, trusted peers operated as a strong system of social support, buffering against the trauma associated with immigration enforcement by breaching the script of silence. For example, Elena described school as a kind of second family. As she explained, “we all know each other. We’ve been knowing each other since fifth grade. So we already have really strong connections because we’ve been growing and our school, they’re like, team and family. So all of us are like our family.” Close friendships at school created spaces of perceived safety in which citizen-children could divulge their worst fears, worries, and anxieties. As Elena noted:

There is this girl. She is my best friend, and we have known each other since the second grade. And I know that her parents don’t have any papers too, so I mostly tell her everything about my life. Because, um, she told me everything about her life, and how she feels scared that she could lose her parents if they are ever sent to Mexico. So we tell each other everything, and we try to help each other out.

In the case of Elena, school enabled citizen-children to foster relationships based on their shared experiences. Moreover, the school administration facilitated classroom curricula designed to break the script of silence and raise awareness about immigration:

See, in our school, like in our history class they teach us about different topics and one of the topics has been, um, immigration. We can connect a lot to that since our school is 99.9% Hispanics. We already know most of the things so sometimes, like sometimes, it’s an emotional class where we stay strong. So, it’s kind of good to know something else that could help you.

Unfortunately, Elena’s experience was rare. Her story reveals the ways in which her links to institutional resources and supportive relationships contributed to her well-being during her father’s detention. Yet, the constellation of individual and family characteristics within her mixed-status family niche also facilitated positive outcomes as well. For example, Elena’s parents had divorced many years prior to her father’s detention. Although her family often spent time together in activities that included both her parents, such as family dinner, Elena did not live with her father. This is not to stay that the detention of Elena’s father was no less distressing to her, but rather that her well-being was shaped by the complex interaction of various factors, including those within the mixed-status family niche.

The Mixed-Status Family Niche

Figure 1 illustrates the elements that comprise the micro-setting of daily life in mixed-status families, or the mixed-status family niche. The niche represents the dynamic interplay between characteristics and behaviors at the individual and family level. Parent characteristics and family cohesion were cited as key to the capacity for the family to act as a system of social support and foster well-being.

Participants noted that their own well-being was deeply tied to their parents’ vulnerabilities and strengths, and thus, parental well-being held the potential to act as a source of comfort or stress for citizen-children. Among participants, family histories of substance abuse or trauma were perceived as particularly stressful, capable of exacerbating the negative effects of immigration enforcement experiences. For example, Marisa, a 13-year old who had reunited with her parents in Mexico following their deportation, noted that her father’s history of substance abuse overshadowed her own adjustment to living in a new environment. Marisa had hoped that in reuniting with her parents in Mexico, she would recover the parental love and support that she needed and desired. Yet, her relationship with her father was strained, and she described him as distant and uncommunicative. As she explained, “With my father taking drugs, he can’t work and he spends a lot [on drugs]. And my mom has to work to be able to keep up the house. He has promised us so many times, he has sworn to us, that he is going to quit, but he never does. Sometimes he just spends the day in the house sleeping.”

In reuniting with her family in Mexico, Marisa was forced to renegotiate her expectations for parental care. Her father’s substance abuse affected his capacity to act as an engaged father and family member, but also produced financial strain. In turn, Marissa’s mother worked extended hours and was rarely home. Marissa noted that there was little family consensus regarding the reorganization of family life in Mexico, which produced significant family conflict.

In contrast, personal strengths were perceived as diminishing the negative effects or stressors that stemmed from immigration enforcement. For example, Marco, a 14 year-old boy, described the importance of a strong work ethic, a factor that was instilled in him by his father. He noted that his father “wants to teach me how to work so I can get our family a better future. I work. I find anything I can do. I help my mom.” Marco’s narrative reflected the way in which he was becoming socialized to become the patriarch of the family, a process that had been accelerated by the fact that his father was facing deportation. Marco sometimes struggled with his newfound responsibilities, but nevertheless, he accepted them. As he explained:

I don’t really have my childhood anymore. I don’t get to play around anymore. I always have to be there. I have to be strong for my brothers. I guess I miss when I was smaller and everything being so innocent for me. The world just being there as a playground for me. A place for me to have fun. Now it’s kind of more like a … How would you call it? Um… obstacle ground. With obstacles. Obstacles I have to go through. I don’t like it, but there’s nothing I can do to take it off of me. I have to be there. It’s my responsibility, and I have to hold it up, and I have to be there.

For Marco, like many citizen-children, age and gender shaped the ways that parents organized household roles and responsibilities. The effects of immigration policies and practices often made it difficult for families to build consistent routines for children, which frequently resulted in confusion or resentment about their roles and responsibilities within the household. This was particularly the case among older girls who reunited with their families in Mexico. For example, in the case of 15-year-old Melina, she felt that the task of sibling and domestic care detracted from her personal motivation to focus on her education. Both her parents were required to work long hours outside of the household, and they charged Melina with caring for the household. As she explained, “[In the U.S.], I didn’t have to clean, or work in the kitchen, or anything. It was pure studying because that is what I spent my time doing. But here, no, here it is different. Here, you spend all your time cleaning the house, taking care of your siblings. Now it’s no longer about studying.”

Reflecting on the change in routines in Mexico, Melina noted that she felt resentful toward her new responsibilities in the household. She proclaimed that she often took it out on her younger siblings by ignoring them. As Melina’s case illustrates, the ways that participants interpreted sudden changes in their routines and responsibilities could produce resentment, frustration and angst, particularly when new household practices were perceived as thwarting their own individual expectations and needs. In contrast, older boys and younger girls in our sample sometimes embraced the opportunity to contribute to the household. Thus, consensus among family members regarding the gendered and age-based organization of household responsibilities contributed to supportive interactions, whereas conflict between personal and family expectations could lead to tension. Individual characteristics and behaviors of children and parents were perceived as shaping the quality of family dynamics, yet many participants were cognizant of the ways in which family dynamics were singularly constrained by the broader political economy of U.S. immigration policy. This recognition led numerous citizen-children to declare, “Things would be better in my family if only my parents had papers.”

Child Outcomes

Figure 1 illustrates how, within the context of the political economy of U.S. immigration policy and encounters with enforcement agencies, the distribution of resources, the arrangement of factors in the mixed-status family niche, and the cultural script of silence interact to shape outcomes for citizen-children. A range of effects upon well-being is suggested, ranging from negative to positive in terms of social and material well-being, the mental and emotional status of children, levels of stress, sense of identity and belonging, and academic performance. In this regard, an important theme to emerge in our research is that there is not a single and definitive profile that encapsulates the experiences of citizen-children in mixed-status families. As illustrated in Figure 1, the effects of immigration encounters on the well-being of citizen-children depend heavily on a multiplicity of factors, reflecting the combined and continued effects associated with the political economy of U.S. immigration policy, the resources available to children and their families, the organization of the mixed-status family niche, and the cultural scripts that individuals draw on to navigate daily life.

Across participants, well-being was differently experienced depending on family circumstances. Without legal status, wage earners were subject to the realities of participating in an unskilled and informal labor market. As a result, most youth hoped their parents could get papers one day so that they would be able to find more satisfying—and better paying—work. As Jose, 13 years old, noted, if his parents had papers, “they could be here and be comfortable. I just know that my dad says that he wants the papers because he wants a better job.”

Additionally, some participants described confusion about their national, ethnic, and legal identities. Having an undocumented parent imposed boundaries of exclusion within school and community settings, even among those who had never experienced parental deportation. For example, 12-year old Anna recalled, “a lot of people are very racist at my school. And a lot of them say, ‘Go back where you came from.’” Experiences of discrimination had a disempowering effect on children’s understandings of their social location within these broader settings. As 14-year old David explained, “I don’t feel like other kids in school. I feel kind of like an outlaw.” For youth who experienced parental deportation, some participants described not knowing where they belonged. Ten-year old Daniel, who accompanied his deported father to Mexico, described “being between two worlds. I have family here and family over there, in both places. I’m like in the middle of Mexico and the U.S.”

The potential threats to well-being described above could produce heightened stress and emotional and mental distress. Fear and worries about their parents’ status, or experiences of parental deportation, made it difficult for youth to engage actively in daily life. One 11 year old, Emma, recounted that every time she left her mother’s side, even at school, she became increasingly nervous that something would happen to her mother and she would not be nearby to help: “It’s just worrying. Like [if I] leave her side. Like not be there to support her.” In another case, Manny, who was 14-years old, began to experience intense headaches and nausea when his father was deported to Mexico. At the time, he was living with his mother, a U.S. citizen, and younger brother. As he described the experience, “It was nerves. Pure nerves. I was scared that something would happen to my mom. Like, someone would hurt her or kidnap her, or something like that, because my dad wasn’t there.” As time passed, his symptoms worsened, and he began to vomit at school, almost daily. In response, the school sent him home because “I couldn’t be without my mom. It scared me.” Finally, his mother took him to a psychologist, who recommended that the family reunite for Manny’s emotional well-being. The family heeded the psychologists’ advice and moved to Mexico to rejoin Manny’s father, upon which Manny’s symptoms stopped.

In our sample, Manny was not alone in his experience of intense distress. Nearly 30 percent of participants in the study described symptoms often associated with anxiety and depression, including intense bouts of crying, loss of interest in activities, difficulties sleeping, loss of appetite, feelings of fear, and suicidal thoughts. Although intense suffering was experienced across participants in our sample, citizen-children who were in the midst of parental deportation processes reported suffering more frequently than children in other groups. For those children who accompanied their deported parents to Mexico, the majority described difficulties adjusting to the different ecocultural environment, and these difficulties could be experienced more intensely depending on the constellation of factors outlined in Figure 1.

Importantly, such experiences were not universal, as described in many of the cases above, and some citizen-children exhibited extraordinary resilience in the face of the many adversities they confronted. Unfortunately, narratives of well-being were described with less frequency across all groups. This was especially the case among citizen-children experiencing parental separation due to detention and deportation at the time of the interview: no child in this group reported doing well. In comparison, only seven citizen-children whose parents had never been deported, and only six citizen-children who accompanied their parents to Mexico, described feeling safe, emotionally secure, and socially connected. Among these children, access to resources to nurture well-being appeared to be a key leverage point in shaping how participants were able to manage their everyday lives. The most fundamental resource, at least from the perspective of citizen-children across groups, was family cohesion. As eloquently described by Karla, following family reunification in Mexico:

Really, I am happy there [in the U.S.], and I am happy here [in Mexico]. I am happy as long as I have my parents with me. If I am separated from one of them, I don’t know what to do. It hurts. I can’t be as happy as I would if I lived with both of them. I have always lived with both of them.

Discussion

In this paper, we have described a framework for conceptualizing the effects of immigration enforcement on the well-being of citizen-children living with their undocumented Mexican parents. The framework illustrates the complex multidimensional, and often multidirectional, factors experienced by citizen-children vulnerable to or directly facing parental deportation. Our findings suggest that the everyday realities facing citizen-children—and the ways in which these realities shape well-being—cannot be reduced to simple explanations. Thus, we situate youth well-being against a backdrop of multiple factors to understand how indirect and direct encounters with immigration enforcement, the mixed-status family niche, and access to resources shape differential child outcomes.

Participants in our study described well-being in terms of a dynamic relationship between personal qualities and the social context surrounding them. In this configuration, the presence or absence of parents emerged as a significant theme. Forced family separations were perceived to be the worst stressor facing participants in our sample. Among citizen-children without experiences of parental deportation, the potential for a forced separation was never far from the minds of the youth in our study. Indeed, the “deportability” of their parents was described overwhelmingly as a major cause for emotional distress (De Genova 2002). For citizen-children facing parental deportation, families were forced to confront whether they should separate so that children could remain in their citizen country, or relocate to Mexico to keep the family together. In deciding whether to separate or relocate, citizen-children had to evaluate the potential emotional, social, and material costs, and brace themselves for the aftermath.

The adverse circumstances facing citizen-children were not limited to forced family separations, and reflected the broader consequences associated with the political economy of U.S. immigration policy. In our study, participants described the varied financial and emotional costs associated with illegality, supporting research that describes the ways in which citizen-children suffer the consequences of their parents’ undocumented status (Chavez et al 1997; Guendelman et al. 2006; Kersey et al. 2007; Perreira and Ornelas 2011). Importantly, our results reveal how the personal strengths of parents and children had the potential to shield children from the negative effects of stressors that stemmed from indirect and direct encounters with immigration enforcement. Strengths were often entwined with the availability of resources that could enhance well-being. Access to financial, educational, extracurricular, mental health, legal, and immigration-related resources buttressed individual strengths and buffered against traumatic experiences related to immigration enforcement and forced family separations. Extended kin and individuals in school and religious institutions emerged as supportive networks that facilitated access to those resources that were important to well-being. Social connection, however, was not without its risks.2 A strong social network was key to the facilitation of well-being among citizen-children, but it’s loss could exacerbate the emotional costs of relocation to Mexico after parental deportation.

In our findings, we point to the cultural script of silence as an additional risk factor that is unique to the experience of mixed-status families. The presence and pragmatics of cultural silence have been well-documented among families and communities of undocumented individuals (De Genova 2002, 2009; Fassin 2001; Menjívar and Kanstroom, 2014). Yet as convincingly argued by Dreby (2012), U.S. immigration policies have “a profound impact on children in Mexican families regardless of the parents’ or children’s legal status or the family’s actual involvement with the Department of Homeland Security” (843). The consequences of illegality, and the cultural logics of silence, extend beyond the boundaries of legal status to affect the lives of citizen-children as well (Zayas 2015; Zayas and Bradlee 2015), and our findings point to the different ways in which silence operates. Although all participants in our sample knew that their parents were undocumented, the cultural script of silence manifested through other processes that encouraged youth to be silent about their experiences of suffering with kin, their peers, and even themselves. Arguably, silencing not only leads to emotional and mental distress, but also fractures citizen-children’s understanding of their place in the world (Fivush 2010). Without a community to safely break the code of silence, citizen-children—and their undocumented peers—must risk the potential integrity of their families should they choose to voice their experiences. It is for this reason that any resistance to the cultural script of silence will be found in the most closed, trusted, and intimate spaces. The experiences of immigrant families will remain, for the most part, hidden, camouflaged, and unspoken. Continued research on the effects of silence on well-being is warranted, especially comparative research that examines the differential experiences of citizen-children and the spectrums of silence.

The categories and factors illustrated in Figure 1 were derived from a rigorous approach to qualitative data analysis. Nevertheless, additional research is warranted to test our model and to determine the extent to which certain factors affect citizen-children in immigrant families of different national origin. Additionally, we did not examine the unique circumstances of children living with psychiatric, cognitive, or developmental disability. Living with disability poses unique opportunities and challenges for families (Farrell and Krahn 2014), which might distinguish their experiences as citizen-children living in mixed-status families. There is a continued need for research that examines the intersections of disability and legal status. Our framework opens the door for a critical discussion of the different factors that affect citizen-children, and it is our hope that subsequent revisions are made to the framework based on the results of additional research. Of particular importance is the need to investigate how resources available in citizen-children’s local environment shape the degree to which cultural scripts, such as the script for silence, and individual coping mechanisms become helpful or harmful.

Our findings provide opportunities to influence immigration enforcement policies and practices. Experiences of family cohesion and dissolution hold particular relevance for this population, signifying potential avenues to reorganize programs and policies to enhance the well-being of citizen-children. For example, the significance of the theme of family separation suggests the need to reconsider detention procedures that thwart family togetherness. Current practices that detain parents in locations that are geographically distant from family households pose serious risks to the emotional well-being of citizen-children (Zayas 2015). In the end, our results point to many resources that were perceived as mattering most to children’s well-being. By offering a comprehensive account of the effects of immigration enforcement, it is our hope that the framework can be used to modify leverage points that offer the potential for change in micro and macro settings in ways that appreciate the diversity of citizen-children’s experiences.

Acknowledgements

Support for this research was provided by National Institute for Child Health and Human Development grant HD068874 to Luis H. Zayas. We express our gratitude to the families who participated in this study

Footnotes

Notes

Researchers in Mexico convened for a group discussion by phone, and researchers in the United States met in person.

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for her/his suggestion regarding this point.

Our participants were aware of their parents’ legal status, and this distinguishes our results from other research that reveals that many children, especially those who are undocumented, remain unaware of their families’ legal status until they attend college (Gonzales 2011). This points to the diversity of experiences with immigrant families, both in terms of how children become aware of legal status differences and the experiences that such knowledge engenders.

References

- Bronfenbrenner Urie. 1979. Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design Cambride: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner Urie 1993. The Ecology of Cognitive Development: Research Models and Fugitive Findings. In Development in Context: Acting and Thinking in Specific Environments, edited by Wozniak Robert H. and Fisher Kurt W., 3–44. Hillsdale: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner Urie and Morris Pamela A.. 1998. The Ecology of Developmental Process. Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development, edited by Damon William and Lerner Richard M., 993–1028. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg Patricia A., Zayas Luis H., and Spitznagel Edward L.. 2007. “Legal status, emotional well-being and subjective health status of Latino immigrants.” Journal of the National Medical Association 99(10): 1126–1131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez Leo R., Allan Hubbell F, Mishra Shiraz I., and Burciaga Valdez R. 1997. “Undocumented Latina immigrants in Orange County, California: a comparative analysis.” International Migration Review 31(1): 88–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Genova Nicholas P., 2002. “Migrant “illegality” and deportability in everyday life.” Annual review of anthropology 31: 419–447. [Google Scholar]

- De Genova Nicholas P. 2009. “Conflicts of Mobility, and the Mobility of Conflict: Rightlessness, Presence, Subjectivity, Freedom.” Subjectivity 29(1): 445–466. [Google Scholar]

- Dreby Joanna. 2012. “The burden of deportation on children in Mexican immigrant families.” Journal of Marriage and Family 74(4): 829–845. [Google Scholar]

- Dreby Joanna. 2013. “The Ripple Effects of Deportation Policies on Mexican Women and Their Children.” In The Other People: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Migration, edited by Karraker Meg Wilkes, 73–90. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell Anne F., and Krahn Gloria L.. 2014. “Family life goes on: Disability in contemporary families.” Family Relations 63(1): 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassin Didier. 2001. “The Biopolitics of Otherness: Undocumented Foreigners and Racial Discrimination in French Public Debate.” Anthropology today (2001): 3–7.

- Fivush Robyn. 2010. “Speaking Silence: The Social Construction of Silence in Autobiographical and Cultural Narratives.” Memory 18(2): 88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales Roberto G. 2011. “Learning to be illegal undocumented youth and shifting legal contexts in the transition to adulthood.” American Sociological Review 76(1): 602–619. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales Roberto G., and Chavez Leo R.. 2012. “Awakening to a Nightmare.” Current Anthropology 53(3): 255–281. [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman Sylvia, Wier Megan, Angulo Veronica, and Oman Doug. 2006. “The effects of child-only insurance coverage and family coverage on health care access and use: recent findings among low-income children in California.” Health services research 41(1): 125–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest Greg and MacQueen Kathleen M. (2008). “Reevaluating Guidelines in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook for Team-Based Qualitative Research, edited by Guest Greg and MacQueen Kathleen M. (205–226). New York: Altamira. [Google Scholar]

- Harkness Sara, and Keefer Constance H.. 2000. “Contributions of cross-cultural psychology to research and interventions in education and health.” Journal of cross-cultural psychology 31(1): 92–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kersey Margaret, Geppert Joni, and Cutts Diana B.. 2007. “Hunger in young children of Mexican immigrant families.” Public Health Nutrition 10(4): 390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl Kathleen A., and Ayres Lioness. 1996. “Managing large qualitative data sets in family research.” Journal of Family Nursing 2(4): 350–364. [Google Scholar]

- Mack Natasha, Bunce Arwen, and Akumatey Betty. 2008. “A Logistical Framework for Enhancing Team Dynamics.” In Handbook for Team-Based Qualitative Research, edited by Guest Greg and MacQueen Kathleen M. (pp. 61–97). New York: Altamira. [Google Scholar]

- Negrón-Gonzales Genevieve. 2014. “Undocumented, Unafraid and Unapologetic: Re-articulatory Practices and Migrant Youth “Illegality”.” Latino Studies 12(2): 259–278. [Google Scholar]

- Miles Matthew B., and Michael Huberman A. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Source Book Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar Cecilia, and Kanstroom Daniel (2013). Constructing Immigrant ‘Illegality’: Critiques, Experiences, and Responses Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ochs Elinor, and Capps Lisa. 1996. “Narrating the self.” Annual review of anthropology 25: 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- Panter-Brick Catherine. 2014. Health, Risk, and Resilience: Interdisciplinary Concepts and Applications. Annual Review of Anthropology 43: 431–448. [Google Scholar]

- Perreira Krista M., and Ornelas India J.. 2011. “The physical and psychological well-being of immigrant children.” The Future of Children 21(1): 195–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peutz Nathalie and De Genova Nicholas. (2010). “Introduction.” In The Deportation Regime: Sovereignty, Space, and the Freedom of Movement, edited by De Genova Nicholas and Peutz Nathalie (pp. 1–32). Raleigh, NC: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Potochnick Stephanie R., and Perreira Krista M.. 2010. “Depression and anxiety among first-generation immigrant Latino youth: key correlates and implications for future research.” The Journal of nervous and mental disease 198(7): 470–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobo Elisa J. 2009. Culture and Meaning In Health Services Research: A Practical Field Guide Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Spradley James P. (1979). The Ethnographic Interview New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco Carola, and Yoshikawa Hirokazu. 2013. “Undocumented status: Implications for child development, policy, and ethical research.” New directions for child and adolescent development 2013(141): 61–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Super Charles M., and Harkness Sara. 1986. “The developmental niche: A conceptualization at the interface of child and culture.” International journal of behavioral development 9(4): 545–569. [Google Scholar]

- Tudge Jonathan. 2008. The Everyday Lives of Young Children: Culture, Class, and Child Rearing In Diverse Societies Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar Michael, Ghazinour Mehdi, and Richter Jörg. 2013. “Annual Research Review: What is resilience within the social ecology of human development?.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 5(4): 348–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner Thomas S. 2002. “Ecocultural Understanding of Children’s Developmental Pathways.” Human Development 45(4): 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner Thomas S. 2007. Well-being, Chaos, and Culture: Sustaining a Meaningful Daily Routine. In Chaos and its Influence on Children’s Development: An Ecological Perspective, edited by Evans Gary W. and Wachs Theodore D., 211–224. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner Thomas S. 2010. Well-Being, Chaos and Culture: Sustaining a Meaningful Daily Routine. In Chaos and its Influence on Children’s Development, edited by Evans Gary W. and Wachs Theodore D. (211–224). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Worthman Carol. 2010. “Survival and Health.” In Handbook of Cultural Developmental Science, edited by Bornstein Marc H. (39–60). New York, NY: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Hirokazu. 2011. Immigrants Raising Citizens: Undocumented Parents And Their Children New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Zayas Luis. 2015. Forgotten Citizens: Deportation, Children, and the Making of American Exiles and Orphans Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zayas Luis H. and Bradlee Mollie H.. 2015. Children of Undocumented Immigrants: Imperiled Developmental Trajectories. In Race, Ethnicity and Self: Identity in Multicultural Perspective, edited by Salett Elizabeth P. and Koslow Diane R. (63–84). Washington, DC: National Association of Social Workers. [Google Scholar]