Abstract

Adequate alertness is necessary for proper daytime functioning. Impairment of alertness or increase in sleepiness results in suboptimal performance and adversely affects the quality of life. While some causes of somnolence are intrinsic to the brain circuitry and neurochemical architecture, others are due to maladaptive behaviors and disorders affecting the normal sleep homeostasis. Identification of the problem and understanding the underlying etiology is the key to timely treatment and better outcomes.

Introduction

Hypersomnia is a state of excessive sleepiness which can result in decreased functioning and affect performance adversely. Hypersomnolence is defined as an inability to stay awake and alert during major waking episodes, resulting in periods of irrepressible need for sleep or unintended lapses into drowsiness or sleep. Lapses into sleep without prodromal symptoms of increasing sleepiness are called sleep attacks. Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is one of the big public health problems of our time and is estimated to cause almost one-fifth of the motor vehicle accidents in this country. Patients with EDS have decreased workplace productivity, lower quality of life and increased risk of work-related injury.1 Population-based surveys by National Sleep Foundation found that about 30% of the respondents suffer from enough EDS to interfere with their quality of life.2

In this article, we will discuss various disorders associated with Hypersomnolence and their division conforms to the current version of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3). Some of them are due to fundamental causes within the brain while some others are due to mild adaptive behaviors, systemic disorders, and medications.

History of Hypersomnia

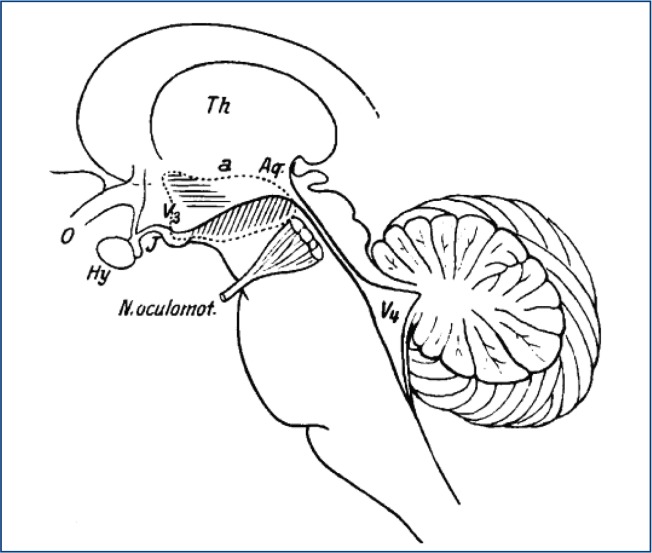

Gélineau (1880) is credited for giving narcolepsy its name though he did not make a clear distinction between episodes of muscle weakness and sleep attacks.3 Loëwenfeld (1902) was the first to name the muscle weakness episodes triggered by emotions as ‘Cataplexy’.4 There were earlier case reports of narcolepsy by German physicians Westphal and Fisher5 while the earliest account of narcolepsy may have been from Thomas Willis (1621–75) who described patients with a ‘sleepy disposition who suddenly fall fast asleep’.6 The epidemic of encephalitis lethargica in the early 20th century sparked significant interest in narcolepsy and sleep research. Von Economo (1930) proposed that the region of the posterior hypothalamus was lesioned in human narcolepsy. The classic tetrad of excessive daytime sleepiness, cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and hypnogogic hallucinations were described by Yoss and Daly at the Mayo clinic.7 (Figure 1)

Figure 1:

Drawing of human brainstem taken from Von Economo’s original drawing. Lesions in the region of the horizontal lines caused prolonged insomnia while lesion in the region of diagonal lines caused prolonged sleepiness. Von Economo suggested that narcolepsy was caused by lesions in the region of posterior hypothalamus (site of the arrow). Picture obtained from Wikimedia Commons.

Neurobiology of Hypersomnia

The state of wakefulness and sleep are controlled by various neuronal systems localized in several brain regions. Hypoactivity of wake-promoting systems, results in activation of sleep-promoting systems and promotion of sleep. In contrast, hyperactivity of wake-promoting systems results in inhibition of sleep promoting systems and promotion of wakefulness. The overarching control on the regulation of sleep-wakefulness is provided by the circadian process (Process C) that provides the alerting signal, and the homeostatic process (Process S) which maintains constancy of sleep. Several neurotransmitter and neuromodulators are involved in the regulation of sleep-wakefulness. However, amongst these the two main neurotransmitters/neuromodulators implicated in hypersomnia are hypocretins (also known as orexins) and prostaglandin D2.

Hypocretins are two neuropeptides (hypocretin-1 and hypocretin-2) discovered in 19988,9 are important neurochemicals implicated in the pathogenesis of type I narcolepsy. They have a very important role in the regulation of wakefulness and muscle tone. Mice with constitutive knockdown of Hcrt gene display narcoleptic attacks with cataplexy-like behavior.10 Intracerebroventricular infusion of Hcrt in wild-type mice increases arousal to the level of complete insomnia, and this effect is abolished in histamine H1 receptor knock out mice. Autopsy studies in humans with narcolepsy also showed loss of hypothalamic Hcrt-producing neurons further implicating Hcrt in type-1 Narcolepsy.

Prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) is an endogenous somnogen that deserves a special mention. Its involvement in hypersomnia has been reported in mastocytosis11 and African sleeping sickness.12 Induction of prostaglandin synthase is seen in the brains of patients with various neurodegenerative diseases suggesting that PGD2 may be the common somnogen responsible for the sleepiness seen in these disorders. The somnogenic effects of PGD2 are believed to be mediated by adenosine13. Several other cytokines including interleukin - 1β, interleukin 6, Tumor necrosis factor α can also induce sleep.

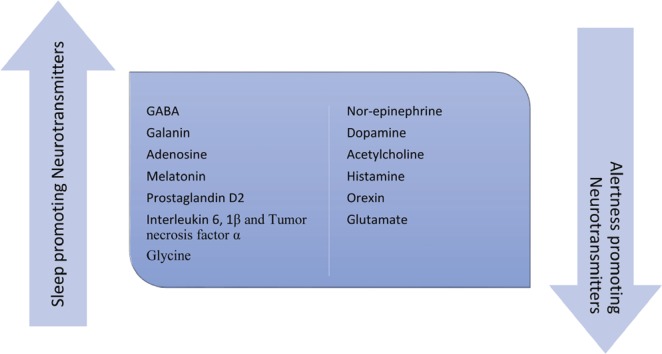

In addition to the somnogens mentioned above, sleepiness due to medication use or withdrawal and in other medical disorders is associated with augmentation of sleep-inducing neurotransmitters or antagonism of alertness-inducing neurotransmitters. (Figure 2)

Figure 2:

The major neurochemicals that are involved in promoting sleep and alertness. The state of the brain and the level of alertness is influenced by the relative overactivity of one group or the other. The circadian and homeostatic processes utilize these chemicals and others to exert their influence on the sleep-wake rhythms of the brain.

Central Disorders of Hypersomnolence

Narcolepsy Type 1

Narcolepsy type 1(NT 1) is characterized by a deficiency of hypothalamic hypocretin signaling. Along with excessive daytime sleepiness, REM sleep dissociation is its other important feature. About 90% of these patients have low or undetectable concentrations of Hypocretin -1 in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Cataplexy is a brief state of reduced muscle tone precipitated by emotional triggers and is the most specific of the REM sleep dissociations seen in Narcolepsy. Cataplexy may not be manifest in all the patients with narcolepsy type I and is very closely associated with low CSF hypocretin levels. Many patients with Narcolepsy type I have disrupted nocturnal sleep. Though not specific, hypnogogic and hypnopompic hallucinations along with sleep paralysis can also be seen. An increased frequency of obesity, other sleep disorders, and psychiatric comorbidities is also observed. Narcolepsy with cataplexy is closely associated with HLA subtypes-DR 2/DR B1*1501 and HLA DQB1*0602. This strong association has led to the hypothesis that autoimmunity is a likely etiological mechanism, potentially explaining the selective neural destruction in the hypothalamus. If the HLA testing is negative, the CSF hypocretin levels are most likely normal.

Most typically, the age of onset is between 10 and 25 years. Sleepiness is typically the first symptom to manifest with cataplexy manifesting usually within one year of onset. Secondary Narcolepsy can also be seen in the setting of inflammatory disorders like encephalitis and tumors or lesions of the hypothalamus.

Narcolepsy Type 2

Patients with Narcolepsy type 2(NT 2) do not have cataplexy and constitute about one-fourth of the narcoleptic population. This disorder shares multiple features seen in NT 1. The exact cause of this disorder is uncertain. Similarly, the underlying genetic and environmental factors associated with NT 2 patients are unknown. The onset of this disorder typically occurs during adolescence. Cataplexy will develop later in the course the disease in about 10% of these patients at which time the disease needs to be reclassified as NT 1. Similarly, a low CSF hypocretin concentration (< 110 pg/mL or <1/3rd of mean concentrations in the population) should warrant a reclassification of the disease as NT 1. Both types of Narcolepsy have early onset of REM sleep after the patients fall asleep. Sleep Onset REM (SOREM) is defined by the onset of REM sleep within 15 minutes of falling asleep, and patients with Narcolepsy should have at least two SOREMs in the MSLT/ Overnight PSG combined.

Idiopathic Hypersomnia

Idiopathic hypersomnia(IH) is characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness without REM sleep intrusion not explained by another disorder. There should be no more than one sleep onset REM on the multiple sleep latency test and the preceding polysomnogram combined. This distinct entity described by Bedrich Roth in the late 1950s was initially called ‘Sleep Drunkenness’ and ‘Hypersomnia with Sleep drunkenness.’14 These patients typically have high sleep efficiency on the preceding polysomnogram and clinically report severe and prolonged sleep inertia (also known as sleep drunkenness) and non-refreshing naps. In the past, IH was divided into two types-one with long sleep time and one without long sleep time. Such a division is no longer used as there is no significant difference between the two groups The CSF hypocretin 1 concentrations in these patients are normal. A recent experiment showed that patients with IH have a bioactive CSF component with a mass of 500–3000 Da that could potentiate GABAA receptor function in vitro.

Kleine-Levin Syndrome

This syndrome is characterized by episodes of severe sleepiness in association with cognitive, behavioral and psychiatric disturbances. Each episode typically lasts for about ten days with prolonged episodes lasting several weeks to months. The first episode is often triggered by infection or alcohol with future episodes occurring every three months or so (range of 1–12 months). During the episodes, patients sleep for up to 20 hours a day only waking up to eat and void. Less commonly, hyperphagia and hypersexuality are also seen during the episodes. In between the episodes, the patients display remarkably normal sleep, feeding behavior, mood, and cognition. The disease starts during the second decade in most of the patients and is more common in males. This syndrome typically resolves after many years. Sometimes, a similar syndrome is also observed in the setting of menstrual cycle and is considered a variant of Kleine-Levin syndrome.

Hypersomnia due to Medication or Substance Abuse

Multiple different classes of medications have sleepiness as their side effect. Table 1 lists the different drug classes and the neurochemical basis of the sleepiness associated with them. Given the concise nature of this review, every medication that has sleepiness as a side effect could not be mentioned.

Table 1.

Classes of Medications with Sleepiness as Their Side Effect

| Class of medications | Drugs | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Hypnotic Medications |

|

The Z drugs (Zaleplon, Zolpidem, and Eszopiclone) act as GABAA agonists. Ramelteon is a melatonin receptor agonist. Suvorexant is an orexin antagonist. |

| 2. Sedatives |

|

Act at the histaminergic and cholinergic receptors. GABAA agonists like barbiturates and benzodiazepines act to modulate the Cl− channel. |

| 3. Drugs of Abuse |

|

Ethanol acts on GABAA receptor. Cannabis acts on Cannabinoid receptors. Opiates act on Opioidergic receptors. |

| 4. Anti-hypertensives |

|

Alpha 1 antagonists like prazosin and terazosin act on the postsynaptic alpha 1 adrenergic receptor while alpha 2 agonists act at presynaptic alpha 2 auto-receptor. |

| 5. Anti-epileptics | Carbamazepine, Valproic acid, | Neurochemical basis of somnolence produced by many drugs in this class is still unknown. Some act as GABA-agonists. |

| 6. Anti-parkinsonian agents | Drugs like Levodopa, dopamine agonists like ropinirole. | Act at dopamine receptors. |

| 7. Skeletal muscle relaxants | Baclofen | GABA receptors; Some have anticholinergic effects |

| 8. Gamma Hydroxy Butyrate | GHB / Sodium Oxybate. Used in the treatment of Narcolepsy | GABAB receptor |

| 9. Antipsychotics | Quetiapine, Olanzapine, Haloperidol, etc. | Dopamine blockade; other effects at histaminic, cholinergic and alpha-adrenergic receptors. |

Hypersomnia Due to a Medical Disorder Sleepiness Despite Adequate Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Sleepiness in the setting of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is usually attributed to the chronic sleep deprivation due to sleep fragmentation. On the same vein, sleepiness is expected to get better when OSA is treated adequately. However, a certain portion of people remains sleepy despite adequate treatment. Individual studies in the past have reported the prevalence rates from 6% to 55%15 while a recent study by Gasa et al. found that about 13% of adequately treated OSA patients still had residual sleepiness with CPAP.16 The affected patients are usually younger, report more fatigue, have higher ESS score at baseline and more PAP-related side effects.16 Other predictors of sleepiness include diabetes, heart disease, mood disorders, hypothyroidism and other sleep disorders, especially insufficient sleep.15,17 The exact mechanism for this condition is unclear thought animal studies showed that intermittent nocturnal hypoxia could result in irreversible damage to neuronal regions involved in sleep-wake regulation.

Post-traumatic Hypersomnia

Hypersomnia can be seen as a complication of head injury in up to 27% people.18 In the acute phase of moderate to severe traumatic brain injury, the CSF hypocretin levels can also be low.19 Imaging studies usually don’t show any significant lesions but may sometime reveal injuries in the hypothalamic region and brainstem.

Hypersomnolence in Neurodegenerative Disorders

Hypersomnolence affects 16–50% of patients with Parkinson’s disease20 and can be seen in up to a quarter of patients with Multiple systems atrophy. Similarly, other parkinsonian disorders, spinocerebellar degeneration, Huntington disease are all associated with hypersomnolence.

Hypersomnolence in Genetic Disorders

Myotonic dystrophy, the most common adult onset form of muscular dystrophy can have hypersomnolence in up to one-third of the patients21. Other genetic disorders associated with primary CNS somnolence include Niemann Pick Type C disease, Norrie disease, Prader-Willi syndrome, Smith-Magenis syndrome, Moebius syndrome and Fragile X syndrome.

Hypersomnolence in Inflammatory, Vascular and Neoplastic Processes

Cerebrovascular disorders, infections, tumors and other inflammatory disorders can also cause somnolence especially when hypothalamus or rostral midbrain is involved

Hypersomnolence in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders

Hepatic encephalopathy, adrenal and pancreatic insufficiency, chronic renal insufficiency and be associated with somnolence. Conditions like hypothyroidism, iron deficiency, vitamin D deficiency have been suggested as possible causes of fatigue and sleepiness but lack a comprehensive characterization of the objective measurements of sleepiness and vigilance.

Hypersomnia in Psychiatric Disorders

Depression and Central hypersomnias share multiple common symptoms. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in NT1 ranges from 15%–37%22,23 while in IH ranges from 15% to 25%.24 On the same note, the prevalence of hypersomnia in Major Depressive Disorder(MDD) can be seen in more than two-thirds of the adult patients. Symptoms of hypersomnia can range from 23% to 78% in patients with bipolar depression(BD).25,26 Hypersomnolence is one of the major features of Seasonal Affective Disorder and can be seen in up to two-thirds of the patients. Patients with MDD have shortened REM sleep latency, increased REM density and duration which may relate to an increased central cholinergic activity. Patients with BD may show disruption of circadian rhythm, especially delay in the sleep phase.27

Stimulant medications should be used with caution as there is an increased risk of psychotic symptoms with higher doses of the stimulants. Preclinical data suggest that H3 receptor antagonists might alleviate depressive symptoms. Sodium Oxybate can induce or worsen depressive symptoms.

Insufficient Sleep Syndrome

Everyone has biologically determined sleep needs for normal level of alertness and wakefulness. When the individual persistently fails to obtain this minimum sleep required, insufficient sleep syndrome ensues with increased somnolence. This state of chronic sleep deprivation has become one of the big public health concerns of the twenty-first century.28 These patients do not have any issue with sleep initiation or maintenance, and physical examination reveals no medical explanation for the sleepiness. Associated features include irritability, difficulty with concentration, attention deficits, distractibility, reduced motivation, and malaise. A trial of sleep extension reverses the symptoms.

Evaluation of Sleepiness

Subjective Assessment

The clinical assessment of patients starts with the subjective assessment of their sleepiness. There are multiple sleep questionnaires that are used to assess subjective somnolence. Most commonly used is the Epworth Sleepiness Scale which has a maximum score of 24 and estimates the likelihood of someone falling asleep in eight different scenarios. Other assessment tools include Barcelona sleepiness index, Stanford sleepiness scale, Karolinska sleepiness scale, time of day sleepiness scale and Leeds sleep evaluation questionnaire.

Clinical Evaluation

Subjective assessment of sleepiness should be followed by a comprehensive sleep history and appropriate investigations. Sleep and wake routines of the patient should be evaluated using sleep log/dairy. An objective assessment of the circadian rhythms can be done using actigraphy. Actigraphy involves monitoring the active and inactive times during a two to four week period to get an overview of the sleep and wakeup times and to determine if the patient has delayed or advanced sleep phase rhythm.

Objective Assessment of Somnolence

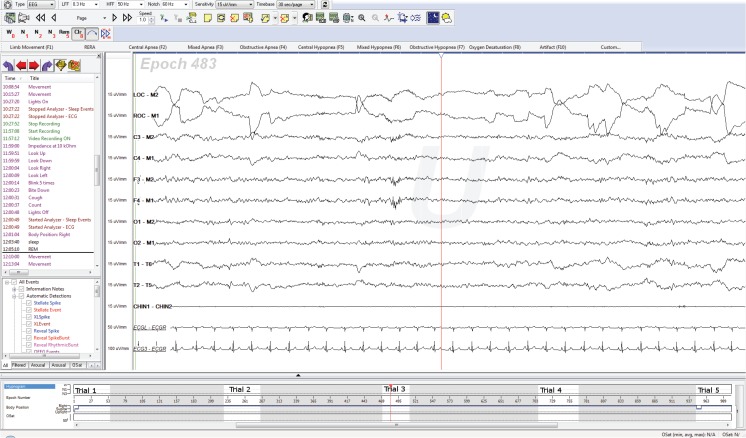

Multiple Sleep Latency test (MSLT) is a type of polysomnogram that can help with identification of patients with Narcolepsy. In this test, the patient is allowed to go to sleep during the five scheduled naps. Sleep onset REM is recorded if REM sleep appears within 15 minutes after sleep onset. The presence of two or more SOREMs along with a mean sleep onset latency of eight minutes or less is diagnostic of Narcolepsy. The MSLT is preceded by a baseline sleep study during which the patient is allowed to sleep to make sure that sleep restriction or other sleep disorders are not influencing the results in the five naps. It is also important to assess the sleep-wake routines of the patients in the preceding one to two weeks preferably using actigraphy. If there is a SOREM in the preceding night, it can be counted towards the total of two required SOREMs for making the diagnosis. (Figure 3)

Figure 3:

A typical MSLT showing the patient having SOREM during trial 3.

Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT) is another test during which the ability of the patient to stay awake is measured. The protocol for this test is not as standardized as MSLT but typically consists of four naps and the patients are asked to stay awake during all the four trials. This is the test of choice when safety is a concern. Other objective tests include Oxford Sleep resistance test, sustained attention to response task, measurement of eye and eyelid movements, pupillometry and driving simulators but are not commonly used in clinical practice.

Treatment of Hypersomnia

The treatment of hypersomnia should be primarily directed at the cause if there is one. Any factor that is adversely affecting the quantity and quality of sleep should be addressed before initiating therapy. Accordingly, the treatment of hypersomnia is both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic.

Non-pharmacologic approaches include – Good sleep hygiene, scheduled daytime naps, and regular physical activity.

Sleep Hygiene

This includes practices to enhance good sleep. This includes avoiding stimulants like caffeine and nicotine before sleep, avoiding heavy meals and alcohol before bedtime, keeping the sleeping environment quiet and comfortable and maintaining a regular sleep schedule.

Scheduled Naps

These have been shown to reduce daytime sleepiness without adversely impacting the nighttime sleep quality. Care needs to be taken to keep the nap time to close to 15 to 20 minutes as naps longer than 30 minutes usually result in sleep inertia. The scheduled naps are very effective in Narcolepsy but are not that well studied in other hypersomnias.

Pharmacological Therapies

Gélineau administered various treatments for narcolepsy including bromides, strychnine, and amyl nitrate. Gowers endorsed caffeine usage and suggested the use of stimulant drugs. Other treatments proposed initially for the treatment of Narcolepsy include intrathecal injection of air, removal of cerebrospinal fluid, X-ray irradiation of the hypothalamic region.3 Amphetamines were first used in the treatment of Narcolepsy in 1935.29

The most commonly used medications to address EDS have a common feature of enhancing dopaminergic tone. Modafinil and Armodafinil are milder and are often the medications of choice at the beginning of the treatment. They act at the dopamine transporter (DAT) and prevent the reuptake of dopamine. Headache and nausea are the most common side effects. Amphetamines salts (methylphenidate, dextro-amphetamine etc.) are generally stronger and more effective in treating EDS but have more abuse potential and side effects. They cause the release of nor-epinephrine and dopamine in the synaptic cleft and act on the DAT to prevent their reuptake.

Sodium Oxybate (Sodium salt of Gamma Hydroxy butyrate(GHB)) is a GABAB agonist and is approved for the treatment of both daytime sleepiness and cataplexy. It promotes slow wave sleep. Its mechanism of action is not fully understood. Several researchers have proposed its activity at its own receptor (GHB receptor).

Pitolisant is an H3 receptor inverse agonist. The histaminergic H3 receptors are regarded as inhibitory auto-receptors and are abundant in the central nervous system. Pitolisant increases histamine release in hypothalamus and cortex. A recent double-blinded study showed its efficacy on both EDS and cataplexy and was better tolerated than modafinil. Pitolisant is not available in the United States at the time of this review.

Flumazenil is an antagonist of the benzodiazepine-binding domain in GABAA receptors. It has been studied in patients with idiopathic hypersomnia and shown to improve psychomotor vigilance and subjective alertness. Clarithromycin is another negative allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor and shows subjective improvement of sleepiness. Levothyroxine also has been successful in patients with IH in improving ESS.

Caffeine is the most commonly used stimulant in the world and can be used in the treatment of EDS in hypersomnias. Higher doses of caffeine have comparable efficacy on EDS as Modafinil but is limited by the side effects.

Other treatments that are currently studied include intranasal orexin for Narcolepsy type I, immune-based treatments for Narcolepsy, Prostaglandin D2 receptor antagonists and Thyrotropin-releasing hormone.

Conclusion

In summary, hypersomnolence is a state of reduced vigilance that affects the daytime function and adversely impacts the quality of life. The level of alertness is mediated by the tone of circadian and homeostatic processes which in turn act through alerting and sleep promoting systems. Any imbalance in these two opposing neuronal systems results either in a state of reduced vigilance and increased sleepiness or difficulty with sleep and insomnia. In the case of hypersomnia caused by sleep disruption, chronic sleep deprivation, metabolic or endocrine disturbance, addressing the underlying etiology will usually be sufficient to improve sleepiness. On the other hand, disorders like Narcolepsy which are due to deficiency of Orexins, treatment options are limited to symptomatic improvement of sleepiness. A thorough history along with a good understanding of disorders of hypersomnolence is necessary for identifying these patients and helping them appropriately.

Biography

Pradeep C. Bollu, MD, (left), Sivaraman Manjamalai, MD, Mahesh Thakkar, PhD, and Pradeep Sahota, MD, (right), MSMA member since 2003, are in the Department of Neurology, University of Missouri - Columbia.

Contact: BolluP@health.missouri.edu

Footnotes

Disclosure

None reported.

References

- 1.Uehli K, Mehta AJ, Miedinger D, et al. Sleep problems and work injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep medicine reviews. 2014;18(1):61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Sleep Foundation; 2009. p. 2009. Sleep in America 2009 poll highlights & key findings. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mignot E. A hundred years of narcolepsy research. Archives italiennes de biologie. 2001;139(3):207–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Löwenfeld L. Ueber narkolepsie. Munch Med Wochenschr. 1902;49:1041–1045. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Todman D. Narcolepsy: a Historical Review. The Internet Journal of Neurology. 2007;9(2) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lennox WG. Thomas Willis on narcolepsy. Archives of Neurology & Psychiatry. 1939;41(2):348–351. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoss RE, Daly DD. Criteria for the diagnosis of the narcoleptic syndrome.. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the staff meetings.; Mayo Clinic; 1957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Lecea L, Kilduff T, Peyron C, et al. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998;95(1):322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92(4):573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chemelli RM, Willie JT, Sinton CM, et al. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell. 1999;98(4):437–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts LJ, Sweetman BJ, Lewis RA, Austen KF, Oates JA. Increased production of prostaglandin D2 in patients with systemic mastocytosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1980;303(24):1400–1404. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198012113032405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pentreath V, Rees K, Owolabi O, Philip K, Doua F. The somnogenic T lymphocyte suppressor prostaglandin D2 is selectively elevated in cerebrospinal fluid of advanced sleeping sickness patients. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1990;84(6):795–799. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90085-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang B-j, Huang Z-l, Chen J-f, Urade Y, Qu W-m. Adenosine A2A receptor deficiency attenuates the somnogenic effect of prostaglandin D2 in mice. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2017;38(4):469. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roth B. Narcolepsy and hypersomnia: Review and classification of 642 personally observed cases. Schweizer Archiv für Neurologie, Neurochirurgie und Psychiatrie. 1976. [PubMed]

- 15.Koutsourelakis I, Perraki E, Economou N, et al. Predictors of residual sleepiness in adequately treated obstructive sleep apnoea patients. European Respiratory Journal. 2009;34(3):687–693. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00124708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gasa M, Tamisier R, Launois SH, et al. Residual sleepiness in sleep apnea patients treated by continuous positive airway pressure. Journal of sleep research. 2013;22(4):389–397. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pepin J, Viot-Blanc V, Escourrou P, et al. Prevalence of residual excessive sleepiness in CPAP-treated sleep apnoea patients: the French multicentre study. European Respiratory Journal. 2009;33(5):1062–1067. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00016808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathias J, Alvaro P. Prevalence of sleep disturbances, disorders, and problems following traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. Sleep medicine. 2012;13(7):898–905. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baumann C, Stocker R, Imhof H-G, et al. Hypocretin-1 (orexin A) deficiency in acute traumatic brain injury. Neurology. 2005;65(1):147–149. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000167605.02541.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnulf I. Excessive daytime sleepiness in parkinsonism. Sleep medicine reviews. 2005;9(3):185–200. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laberge L, Begin P, Montplaisir J, Mathieu J. Sleep complaints in patients with myotonic dystrophy. Journal of sleep research. 2004;13(1):95–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2004.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dauvilliers Y, Paquereau J, Bastuji H, Drouot X, Weil J-S, Viot-Blanc V. Psychological health in central hypersomnias: the French Harmony study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2009;80(6):636–641. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.161588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Billiard M, Partinen M, Roth T, Shapiro C. Sleep and psychiatric disorders. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1994;38:1–2. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roth B, Nevsimalova S. Depresssion in narcolepsy and hypersommia. Schweizer Archiv fur Neurologie, Neurochirurgie und Psychiatrie= Archives suisses de neurologie, neurochirurgie et de psychiatrie. 1975;116(2):291–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akiskal HS, Benazzi F. Atypical depression: a variant of bipolar II or a bridge between unipolar and bipolar II? Journal of affective disorders. 2005;84(2):209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Detre T, Himmelhoch J, Swartzburg M, Anderson C, Byck R, Kupfer D. Hypersomnia and manic-depressive disease. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1972;128(10):1303–1305. doi: 10.1176/ajp.128.10.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geoffroy PA, Boudebesse C, Bellivier F, et al. Sleep in remitted bipolar disorder: a naturalistic case-control study using actigraphy. Journal of affective disorders. 2014;158:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bollu PC, Goyal M, Sahota P. Sleep Deprivation Sleepy or Sleepless. Springer; 2015. pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prinzmetal M, Bloomberg W. The use of benzedrine for the treatment of narcolepsy. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1935;105(25):2051–2054. [Google Scholar]