While military medicine by the beginning of the 19th century looked much better than at any time in the previous millennia and a half, both trauma care and military public health were primitive by today’s standards. The development of what we now know as modern military medicine occurred over the course of the late 19th century, and into the 20th. While this evolution took place across Europe as well as in North America, we will concentrate upon the American experience. The European experience was essentially similar. Medical and trauma care made slow progress during the limited wars of the 19th century, but was greatly challenged by smaller wars in adverse environments. In the case of Europe, those would be the Crimean War and then the Boer War in South Africa. In our experience, this would be in the Caribbean and the Far East.

After the Napoleonic wars, which included our War of 1812, the United States had few major conflicts for 50 years. But then, we found ourselves in the bloodiest conflict of our history. The American Civil War was fought with mass armies, modern industrial technology, railroad transportation, and telegraphic communications.

Unfortunately, its health care was barely up to the 18th century. Both armies had physicians, but there was only a rudimentary hospital and evacuation system. Both armies depended heavily upon civilian physicians and makeshift facilities to care for their injured soldiers. Even “army doctors” were contracted civilians. Public health was terrible. Many soldiers died of disease, often even before reaching the battlefield. Sanitation was abysmal. Epidemics of dysentery, pneumonia (“camp lung”), and typhus swept the camps. And yet, nothing was done after the war to change things.

The next war, the brief Spanish-American War (1898), was fought in the tropics, notably Cuba and the Philippines. Typhoid, yellow fever, and malaria were new to American troops, and killed far more than enemy action. There was little organization, few supplies, and poor use of resources. But the war was highly publicized in the newspapers of the day. After the war, there was a great public outcry about disease. The so-called “typhoid board,” often called the Reed commission, was set up during the war, and made a number of recommendations about sanitation, malaria control, and mosquito control. The Reed commission paved the way for the construction of the Panama Canal, overcoming the high rate of yellow fever among the workers in previous attempts to dig an Atlantic to Pacific canal. Walter Reed was an outstanding Army physician, one of the true heroes of the Army medical corps. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1.

Walter Reed, MD

He had immense influence during and after the war. He died in 1902, of appendicitis, but his work was carried on. The subsequent Dodge commission conducted a much more comprehensive review of the shortcomings of the Army medical services. These included poor preparation, poor sanitation in the camps, and failure to organize nursing services. As a result, there was a major re-organization of the Army’s medical support. So finally, during the first decade of the 20th century, the Army recognized the need for doctors, nurses, hospitals, corpsmen, and, in short, today’s medical services. Immediately prior to World War I, the Army was headed by a chief of staff who was a physician, Leonard Wood, MD. (See Figure 2.) He oversaw much of the transition of the Army medical service into a modern military medical system.

Figure 2.

Leonard Wood, MD

Why did it take so long, both here and in Europe? In all “civilized” countries, military medicine remained much worse than it should have been during the entire 19th century. There were three reasons. First, until the 20th century, most countries were run by aristocrats. Even in such ostensible democracies as England, they were the politicians, the generals, the senior military bureaucrats. Doctors were middle class, below the aristocracy. Simply put, nobody wanted to listen to them. This had been going on for centuries. Once, in the middle ages, physicians had a certain status as churchmen, but even that was incomplete. Barber-surgeons like Ambrose Paré were not only below the aristocracy, they were definitely lower class. Jean Larrey, a plebian, could succeed in only Revolutionary France. But such a man was looked down upon even in France, and would have been a second class citizen anywhere else in Europe. Second, public health itself was poorly understood. Cities down through the 19th century were, to put it bluntly, cesspools. Someone in the early 20th century commented that were it not for the automobile, city streets would have been three feet deep in horse manure. The countryside wasn’t much better, just less densely populated. Epidemics swept through Europe at regular intervals. Similar epidemics swept through military camps on a regular basis. Third, senior military officers were taught strategy and tactics. Logistics was a poor third. And the sort of logistics which concerns caring for and evacuating the wounded is not a pleasant topic, nor one which will win prestige for an ambitious officer. Much less public health. A famous comment made by a Civil War era general to a physician who wanted to clean up the camp was, “Don’t worry. All Army camps smell that way.” There was a sort of pessimistic complacency. Senior officers knew that if they could keep down losses from disease, they would have more men to fight. But they didn’t think anything could be done. Even if it could, they didn’t want to do it themselves.

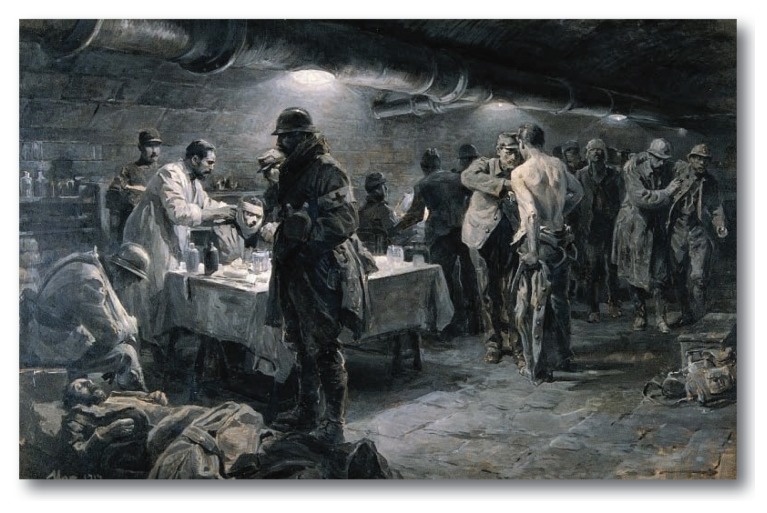

The First World War was fought largely in the trenches of the Western Front. That’s not the full story, but it was and remains the public image. Trench conditions were miserable from a military standpoint. They were a disaster for public health. Sanitation was so bad that after a week or two in the trenches, troops had to be rotated back of the lines to be deloused, thoroughly cleaned, and provided with fresh clothing and equipment. Even so, disease was common, and wound contamination universal. Facilities were largely improvised, and soldiers were collected in the open to await care. All of this made wound care much more difficult. (See Figures 3 and 4.)

Figure 3.

Aid Station and Ambulance in World War I.

Figure 4.

Aid Station in World Ward I.

Even acknowledging all of the difficulties imposed by trench conditions, the casualty care system was still much better than in any previous war. Special military units, called ambulances were charged with picking soldiers from the battlefield and transporting them to aid stations, and then to field hospitals. So-called casualty clearing stations were used to collect the wounded, and load them onto hospital trains. These were staffed with nurses and orderlies, and equipped to care for even difficult wounds. There were base hospitals and convalescent facilities both on the French coast and in England. As the American Army deployed to Europe in 1917–18, hospitals, doctors, nurses, and ambulances went with them.

Wounds were usually contaminated with the mud of the trenches. For this reason, wounded soldiers were routinely given tetanus toxoid. Wound care emphasized debridement of devitalized tissue and thorough cleaning with antiseptic solution (Dakin’s solution, to be precise). Aseptic technique was (usually) used in operating rooms, better anesthesia was available. Bowel injuries could be routinely repaired. Intravenous fluids were available, as were blood transfusions (sometimes). Radiography had only been invented some 16 years before, but was deployed on the battlefields by 1914. As an index of how much things had changed, mortality following amputation had been 25% in the American Civil War, and was 5% in World War I. Deaths from wounds dropped, but deaths from disease dropped even further. Far fewer soldiers died of disease as a percentage of total deaths than ever before. And this was despite the influenza epidemic of 1918–19, which claimed many victims at the end of the war.

An example of the greatly improved casualty care was the experience of Robert Graves, a young British officer who would later become one of the premier writers of the century. His open chest injury was so severe that he was triaged to “expectant,” and his death reported in the London papers. Yet he survived the injury itself, empyema, and the resulting broncho-pleural fistula. After he was evacuated to England, he placed a notice in the papers to the effect that reports of his death had been much exaggerated.

The First World War claimed nine million soldiers, and at least seven million civilian lives. Civilian estimates vary widely, and the true figure is probably unknowable. In 1918–20, over the course of the influenza epidemic (misnamed the Spanish flu), some 20 to 40 million people died. Half of all American soldier deaths from disease were due to influenza, many in the training camps in the United States itself. The extent to which the war caused the flu epidemic has been debated ever since. But the epidemic probably killed more people than the war.

Over the inter war years, and by World War II, many medical advances had been incorporated into military medicine. Blood and plasma transfusions, widespread use of intravenous fluids, antibiotics (but limited to penicillin and sulfonamides), endotracheal intubation, thoracic and vascular surgery, and the care of burn wounds. Plastic surgery had received a huge impetus from the World War I treatment of disfiguring wounds, and continued to advance before and during World War II. This war’s casualty lists were huge. There were some 20–25 million combatants killed, and 40–50 million civilians.

Both casualty care systems and public health continued to advance, but these were more a matter of degree than the much more dramatic improvements seen during World War I. (See Figure 5.) However, environments were equally challenging. Tropical environments were particularly difficult. It was a definitely mixed benefit that improved public health and sanitary measures enabled armies to operate in areas that were difficult even to live in. Tropical medicine began to assume a greater role in military medicine. And as always, at the point of the spear, casualties were high, resources limited, and medical support difficult. The many amphibious operations during the war were extremely challenging. Even when the operation was supported with hospital ships, initial care and evacuation offshore was difficult.

Figure 5.

Field Hospital, Italy, World War II.

A major contribution of the 20th century was the widespread recognition and treatment of what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. It has probably existed back into history. There are case reports from the Civil War, for example. During World War I, it was sometimes called “shell shock,” which probably included cases of actual brain damage. More often soldiers suffering from PTSD were diagnosed as “cowardice.” Soldiers were shot for it in the British, French, German, Austrian, and Russian armies. As the war dragged on, it became better recognized, but its treatment varied widely. The Russians tried to treat near the front lines, sending the soldiers back to their units as early as feasible. We adopted that practice, and in fact, armies today still treat psychiatric casualties this way. What may seem heartless, actually proved to be the most effective way to treat PTSD and to prevent long term sequelae. The recognition of PTSD as a psychiatric disease of war was not firmly established until World War II. They called it “combat fatigue.” But whatever they called it, they recognized it and treated it.

Both the Korean and Vietnam wars proved to be severe challenges to the medical system, the former for cold weather operations, and the latter for tropical and jungle warfare. The medical services gradually adapted to these challenges. By the time of the Vietnam war, for example, operations could be done in contained, air-conditioned operating theaters that were containerized so as to be moved close to the battlefield. (See Figure 6.) Helicopter evacuation supplemented ground ambulances, and air transport replaced hospital trains. The system of progressive levels of casualty care has turned into doctrine, and remains the guiding principle for casualty care.

Operation during the 40 years since Vietnam have produced far fewer casualties, yet have challenged the military medical services in different ways. Small unit operations at greater and greater distances have increased reliance on medical corpsmen, who are now trained to at least the level of civilian Emergency Medical Technicians, and often higher. Casualty care and evacuation in a hostile civilian environment, always a problem in warfare, has been made more complex by opponents who refuse to respect the non-combatant status of medical facilities and personnel.

What can we say about military medicine today? Most of us focus on combat casualty care, as has been discussed over the past few paragraphs. And indeed, this is the primary focus of the system. We put huge resources into this, as well we should. The death rate for soldiers who survive long enough to reach medical care today is only a few percent. Overall casualty rates have decreased steadily since the middle ages, even though today’s weapons are far more powerful than those our ancestors fired off at one another.

Yet it is just as important to look at military medicine as a system of disease treatment and prevention. Deaths from disease have dropped far more than deaths from battle. In the Civil War twice as many soldiers died of disease as from battle. In World War I, for the U.S. Army, the numbers were about equal. In World War II, only half as many, and in Vietnam, only one-fifth. These great improvements have come from the disciplines of what we now term “deployment medicine.” We have learned, often painfully, that these are as important to the overall health of the military forces as the system of casualty care. Perhaps, from a purely military standpoint, even more so. A soldier ill from disease is removed from the combat strength as surely as one who is wounded. Yet, the illness is usually preventable. Deployment medicine is, in the Army’s unique jargon, a “force multiplier.”

As we watch combat operations on the nightly news, most of us look at these environments with horror and disgust. Everything looks destroyed, broken down. That’s true. In the first place, wars are not usually fought in vacation spots. Even when fighting occurs in pleasant places, they quickly become unpleasant places. Differences in climate aside, one war zone looks much like another. To maintain the health of armed forces, deployment medicine must address many issues. Adverse environments, with heat, dust, sand, wind, and/ or cold. Insect-borne diseases such as malaria, yellow fever, and typhus. Food and waterborne diseases, such as cholera and dysentery. Epidemics, such as meningitis and hepatitis. Skin diseases. Parasitic diseases. And above all, the inevitable social breakdown, with civilian suffering, refugees, and the inevitable victimization of the weak by the strong.

There are five basic constraints which deployment medicine must overcome. Resources are always scarce. The environment is always adverse. Populations are usually hostile, if not deadly. Disease is always present, lurking in the corner. And finally, change itself is constant.

War is inhumane, and terrible. Yet, war has always been with us. The 20th century has been a century of war. Future generations will no doubt call it, “The Awful Twentieth Century.” But one of our greatest medical accomplishments of the last 100 years, among a host of other accomplishments, is the system of military medicine. Today’s military medicine combines combat casualty care with public health. As William Tecumseh Sherman put it, “War is all hell.” But we can take pride that we have done and are doing as much as humanly possible to reduce the horrors, and to save those who have been broken on the modern battlefield.

Figure 5.

Field Hospital, Oregon, ca 2004.

Biography

Charles W. Van Way, III, MD, MSMA member since 1989 and Missouri Medicine Contributing Editor, is Colonel, US Army Reserve, Medical Corps, Retired; Emeritus Professor of Surgery at the University of Missouri - Kansas City School of Medicine; and Director of the UMKC Shock Trauma Research Center.

Contact: cvanway@kc.rr.com

Reprinted with permission. Kansas City Medicine 2016.

Footnotes

Reprinted with permission. Kansas City Medicine 2016.

References

- Bull S. Trench: A History of Trench Warfare on the Western Front. Osprey Publishing; Oxford, England: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright FF, Biddiss MD. Disease and History. Dorset Press; New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel RA. A History of Military Medicine from Sumer to the Fall of Constantinople. Potomac Books; Washington, DC: 2012. Man and Wound in the Ancient World. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel RA. Between Flesh and Steel: A History of Military Medicine, from the Middle Ages to the War in Afghanistan. Potomac Books; Washington DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Graves R. Good-bye to All That. Vintage International; Random House, New York: 1998. First published in 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Keegan J. A History of Warfare. Vintage Books; Random House, New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Martin AA. A Surgeon in Khaki: Through France and Flanders in World War I. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln NE: 2011. Originally published 1915 E. Arnold, London. [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew E. Wounded: A New History of the Western Front in World War I. Oxford University Press; Oxford, England: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Scotland T, Heys S, editors. War Surgery 1914–18. Helion & Co; Solihull, Englannd: 2012. [Google Scholar]