War is an actual, intentional, and widespread armed conflict between political communities.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Care of the injured soldier is as old as war. And war is as old as history. Perhaps older. People were fighting and hurting one another back into the old stone age, long before organized societies and armies. And others were caring for the injured. So one can make the argument that military medicine should go back a very long way. Yet, what we now call military medicine is really a product of the 19th and 20th centuries. It was in fact during the Napoleonic wars at the beginning of the 19th century that the organized practice of military medicine began, and it didn’t reach its modern form until the beginning of the 20th century.

What is this human activity that we call war? When did they invent it? How does it differ from simple fighting? As noted above, the definition of war includes nations, states, or their equivalent. In other words, civilization. No, not the computer game. The real thing. Primary civilizations appeared in four areas, widely separated in time and place. In chronologic order, from around 4000 BCE to around 1500 BCE, these were the Middle East, in Mesopotamia and Egypt; the Indus River valley, in present-day Pakistan and India; the Yangtze River valley in China; and the Americas, specifically meso-America and the Andes. All were agriculturally-based, and featured organized governments and armies supported by hereditary ruling and military castes. Without exception, all were warlike. Initially, it was thought that the meso-American civilization of the Maya were peaceful. The latest archeologic evidence is clear that they were not.

But when we say that armies of the ancient world were organized, that does not follow that they were organized as we would do so today. The treatment of casualties is very obviously an inherent part of military organization. But wound care and medicine itself varied widely from one culture to another. In ancient Egypt, for example, medicine was both sophisticated and highly specialized. The Smith Papyrus (1600 BCE) describes wound treatment, fracture splinting, and cauterization to control bleeding. Egyptian clinical practitioners were deployed to garrison posts. This can be seen as the beginning of a formal military medical service. Babylonian-Assyrian medicine (1000-600 BCE) had physician-priests for magic and ritual, but also had the “asu,” pragmatic practitioners who became the first full-time military physicians. On the other hand, the Persians, whose empire stretched from the Middle East to India around 500 BCE, had no military medical service, and very rudimentary wound treatment.

In the ancient world, Roman military medicine most closely approached what we have today. The Greeks had a long tradition of practical medicine, although handicapped with the “humoral” theory of disease. The Romans were still more practical. The Roman army had organized field sanitation, well-designed camps, and separate companies of what we would now call field engineers. They had a much better grasp of sanitation and supply than anyone else before, or for a long while after. Their camps were laid out in a way as to protect their water supply and to locate latrines downstream. Their permanent camps included separate hospitals. They had medical corpsmen, whom they called “immunes.” They practiced front-line treatment, beginning with soldiers treating one another, and they appeared to have a casualty collection system within each legion. They evacuated wounded legionnaires back down their well-organized support and logistics chains. They had more sophisticated wound treatment than anyone up to that time. Roman medicine reached a high point which was not to be equaled until the 18th Century.

It would be reasonable to argue that the Romans actually had something which we would call military medicine. Because of their improved sanitation, their armies suffered somewhat less from the epidemics which swept military camps, but only by comparison with their opponents. Two-thirds of their casualties were still due to disease. Their world-view included no such thing as bacteria or protozoa, and such things as immunizations were two millennia in their future. And, perhaps most important, their practices did not outlive their empire.

After the Romans came a period of regression, which has always been a bit difficult to characterize. It is probably best known for our purposes as the Early Middle Ages. The term “Dark Ages,” implying a regression into barbarism, has become politically incorrect. Besides, it isn’t really accurate. The people of the post-classical world often regarded themselves as quite civilized. In fact, they often regarded themselves to be Romans. The Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine) so styled themselves until 1450, and the ruler of Russia was called “Caesar” (Czar) up into the 20th Century. But, I digress.

The early medieval armies were built around warlords and their bands of retainers. National armies, except for the Byzantine Empire, largely disappeared. Forces were made up from nobles and followers, tied to one another by a chain of reciprocal obligations and duties. We now call this the Feudal System. Whatever its name, it basically broke down armies into units the size of companies or smaller, with little central organization. All of the sophistication of the Romans regarding sanitation and camp organization was completely lost. Medical care was by whoever the lord happened to have in his retinue. The wounded were cared for by servants, camp followers, and other warriors. The lord might have a physician, but no more than one or two. In short, if a soldier was wounded, he was pretty much on his own. Most battles were between small armies, because anything over a few thousand men, could not be supplied, so the numbers of wounded were relatively small.

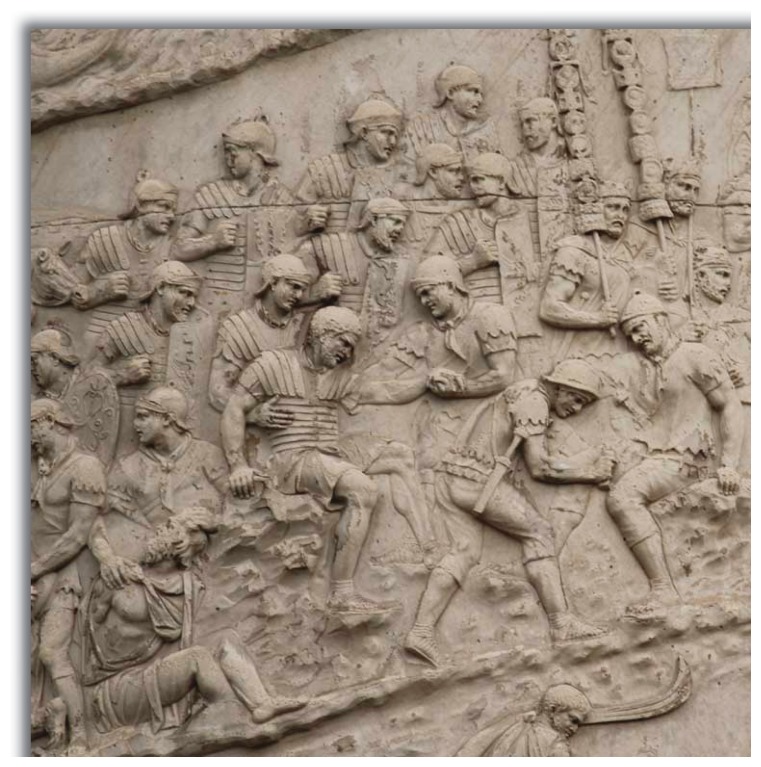

Roman soldiers wounded in battle or afflicted by illness or disease would find themselves in the hands of the medical corps. In battle wounded soldiers may have been treated by field medics, milites medici or capsarii so-called after the capsa or box for bandages that they commonly carried. Right, Capsarii treating the wounded as depicted on Trajan’s Column, Rome, Italy.

By the Late Middle Ages, organization had improved markedly. Armies of 10,000 to 15,000 men were routinely fielded. At the famous battle of Crécy, 1346, about 10,000 English beat 20,000 French, using the longbow, a weapon which dominated battle for the next 200 years. Over those years, gunpowder weapons evolved, and armies began once again to specialize. Cavalry and infantry were always present, but there began to be, besides archers, pikemen, engineers, artillerists, and finally musketeers. Medical organization did not advance at the same pace. Bandsmen, who typically weren’t much good at fighting, were designated to evacuate the injured. And again, camp followers, personal servants, and other members of the lord’s retinue were pressed into service. Local doctors and surgeons were conscripted into caring for the wounded. Indeed, this last persisted for a surprisingly long time, and was seen in our Civil War, as well as most other 19th Century wars.

The Early Modern Period was from about 1450 to 1700. (“Renaissance” has fallen into disuse, something like “Dark Ages.” Feel free to substitute if you wish.) This era was marked by the widespread use of gunpowder weapons and the rise of national armies. Paid soldiers, often with standardized weapons and uniforms, replaced the old feudal levy. The thing about the new weapons was, they used things up, like powder and shot. Someone had to make replacements, and then those had to be transported forward to the fighting line. Cannon and even early personal firearms had to be made in a rear area and then transported forward to make good losses and damage. Armies became too big to live off the land. Horses required fodder. So a system of what we now call logistics began to emerge. Of course, this would have been no mystery to the Romans. But around 1500, it was a major innovation. But for a number of reasons, a system of medical support failed to evolve in the armies of the day.

To be sure, medicine wasn’t very effective. And it was during this time that medicine re-discovered Greco-Roman medicine. Unfortunately, they latched on to the humoral theory of disease, and began to combine that with astrology. To compound a medicine, one needed to diagnose which humors were involved, then determine the house of the zodiac under which the patient was born, and then prepare the appropriate medication. If this seems odd, reflect that we have faithfully collected our patients’ date of birth down to the present day. At least today, we use it for identification purposes, so the effort isn’t entirely wasted.

The problem with all of this theory was that it wasn’t much use in treating a wound, or for that matter lancing a boil or removing a tumor. So these sorts of things fell to the less educated but more practical barber surgeons. These men (mostly) were the ones to accompany armies, and they were the ones who actually carried out wound treatment and care. The most famous barber-surgeon of this period was Ambrose Paré (1510–1590). From a family of barber-surgeons, he started as a battlefield surgeon, and eventually was in the royal service of five successive kings of France. He re-discovered the old Roman remedy of treating wounds with a compound which included turpentine, a harsh but effective wound antiseptic. He re-discovered (from Galen) the use of ligatures to tie off bleeding vessels, rather than using hot iron cautery or boiling oil, two of the “remedies” of the day. He even invented an early hemostat. He published, in 1545, The Method of Curing Wounds Caused by Arquebus and Firearms, a book cited by others for centuries.

But eventually, medical science moved beyond the limits of the old theories. Great advances were made during the 18th century. Jean Louis Petit introduced the tourniquet, in 1718. Forceps were used to remove bullets. Pierre-Joseph Desault described the debridement of wounds. There were three textbooks of military medicine, John Pringle (1752), Richard Brockelsby (1756), and John Hunter (1794). Hunter’s views on the treatment of wounds dominated the next century, and many of his principles survive today. Perhaps most significantly, John Pringle, about 1740, described and identified the epidemic disease of typhus, one of the scourges of the battlefield.

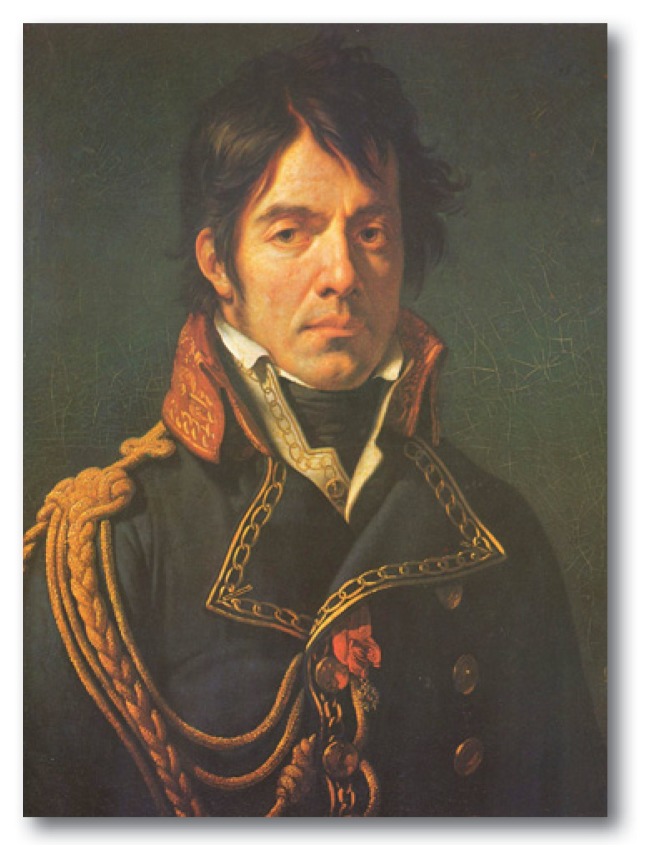

Much of this came together in the epic wars which began the 19th Century, the Napoleonic Wars. Armies of 100,000 or more ranged throughout Europe, almost forcing the recognition of a need to care for the wounded, and to provide some organization to the medical system. This was done best in the French army. Dominique Jean Larrey, surgeon-in-chief of French armies from 1797 to 1815, contributed in many ways to modern military medicine. (See Figure 1.) He established the criteria for “triage,” in case you were wondering why we use a French term for that. He invented the “ambulance volante,” or flying ambulance, which imitated Napoleon’s “flying artillery.” These were horse-drawn carriages, which could move quickly around the battlefield to provide evacuation. (See Figure 2.) He staffed ambulance units with corpsmen and litter-bearers, used initial care just behind the battle, and formalized the use of field hospitals a few miles back from the battle. He is considered the first modern battlefield surgeon.

Figure 1.

Dominique Jean Larrey, surgeon-in-chief of Napoleon’s armies.

Figure 2.

The “ambulance volante,” or flying ambulance.

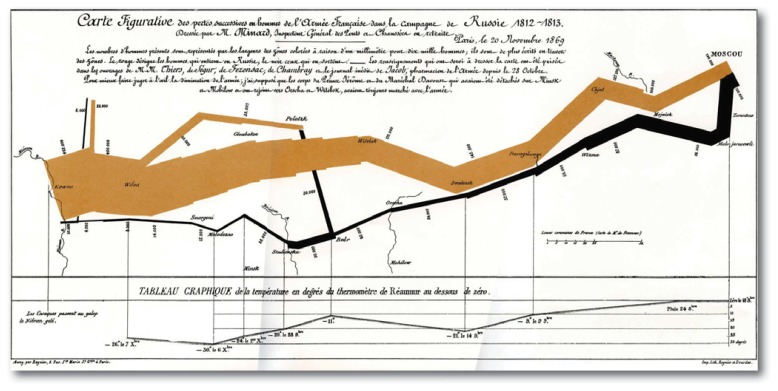

In 1812, the French Emperor decided to invade Russia. Leaving Berlin with 600,000 men, he returned with 50,000. Of 800 physicians with the army, 300 made it back. Minard’s famous graphic is a milestone in its own way, shows the grim reality of the failed campaign. (See Figure 3.) What happened? Starvation, cold, exposure, typhus, diarrhea, and pneumonia. Poor logistics, corruption in the Army administration, poor attention to medical issues, and the Russian weather all contributed. Larrey ended the campaign as a hero for his efforts on behalf of the wounded and ill. But even he was unable to prevent the disaster. He could control the treatment of the wounded, and he did so. But he had no say in how the army was organized, nor how sanitation was carried out, nor over anything we would now term public health.

Figure 3.

The graphic of Napoleon’s Russian campaign, as constructed by M. Minard.

Napoleon’s invasion of Russia was perhaps the best documented military misadventure up to the 20th Century. Despite that Hitler’s Germany made the same series of mistakes in 1941 and thereafter. And as someone put it after that war, “At least Napoleon took Moscow. Hitler did not.”

By the beginning of the 19th century, then, Western European military medicine had equaled, and maybe surpassed in some ways, the military medicine of the Romans of the 3rd and 4th centuries. There was still a long distance to go. The place of physicians within the society of the day, and especially within the military caste, was relatively low. In an aristocracy, as most European countries were, physicians rank somewhere down in the social scale between merchants and shopkeepers. Barber-surgeons were still lower, and were regarded as skilled craftsmen. Put plainly, no military leader was going to listen to a physician tell him how to run a military camp, or take care of his troops. Indeed, Larrey became a French folk hero, in large part because he was willing to fight the higher command of the French army to see that soldiers under his care were well-treated. His efforts to care for the sick and wounded during the retreat from Moscow were things of legend.

In the last part of this series, we will move to the New World. American military medicine was no better, and perhaps a bit worse, than that of Europe. We had far greater distances, fewer doctors, and fewer resources. As the 19th century passed, we learned bitter lessons in the Civil War, and the Spanish-American War, and we made great progress in the early 20th century. Stay tuned.

Biography

Charles W. Van Way, III, MD, MSMA member since 1989, and Missouri Medicine Editorial Board Member, is Colonel, US Army Reserve, Medical Corps, Retired; Emeritus Professor of Surgery at the University of Missouri - Kansas City School of Medicine; and Director of the UMKC Shock Trauma Research Center.

Contact: cvanway@kc.rr.com

References

- Cartwright FF, Biddiss MD. Disease and History. Dorset Press; New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel RA. A History of Military Medicine from Sumer to the Fall of Constantinople. Potomac Books; Washington, DC: 2012. Man and Wound in the Ancient World. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel RA. Between Flesh and Steel: A History of Military Medicine, from the Middle Ages to the War in Afghanistan. Potomac Books; Washington DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Keegan J. A History of Warfare. Vintage Books; Random House, New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]