Abstract

The computer has become an integral part of the exam room and plays an important role in provider-patient interaction. The special arrangement of the provider-patient and computer as well as the provider’s computer skills and hardware knowledge play a pivotal role in patient satisfaction, engagement and productivity. Patient satisfaction and engagement play an ever increasing role as medicine migrates to value-based reimbursement. How a physician uses the computer and interacts with patients in the exam room can encourage or discourage participation. Many physicians practice in rooms ill designed for optimal computer use. Learning how to adapt and incorporate the computer is a key patient interaction skill required of all clinicians. This paper discusses the research supporting this activity and describes how we are attempting to teach this to resident physicians in our practice.

Background

Electronic medical records (EMRs) are a fundamental requirement for medicine today and will continue to play increasingly important functions in our move towards value-based reimbursement. Effective patient-clinician communication is the foundation of patient engagement necessary to deliver patient-centered care. Many clinicians have expressed concerns that technology is interfering with this communication. A comprehensive review of the published material studying the effect of computers in the exam room was completed by Noah Cramption, Shmuel Reis, and Aviv Shachak.1 Their review demonstrated that computers affect the patient encounter both positively and negatively and suggests application of best practices to reduce the negative impact. Other studies have corroborated most physicians are not only accepting and reliant on EMRs but generally satisfied with many of the features.2 Patients certainly do not indicate a sense of loss of rapport with their physicians after introduction of an EMR in outpatient settings.3, 4

As suggested by Crampton, et al., effective use of computers in the outpatient exam room depends heavily on a physician’s computer and communication skills that includes both verbal and nonverbal behavior. Relatively simple modifications of how physicians position themselves in the exam rooms or how exam rooms are configured can facilitate or interfere with effective communication.5

The American Academy of Family Practice recognized the potential for computers to enhance the visit experience in a 2006 Family Practice Management journal offering, “10 Tips on how to effectively use computers in the exam room.”6 The ten tips were:

Use mobile computer monitors

Learn to type

Integrate typing around your patients’ needs

Reserve templates for documentation

Separate some routine data entry and health-care maintenance issues from your patient encounters

Start with your patients’ concerns

Tell your patients what you are doing – as you are doing it

Point to the screen

Encourage patients’ participation in building their charts

Look at your patients

A common theme in these tips is for physicians to integrate the exam room computer into the clinic workflow. Doing so reduces redundant work and encourages the patient to participate in the process. This involves training and practice for most physicians.

Some schools like the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hills have created a Clinical Skills Center with 16 exam rooms to teach students how to interact with patients in a controlled setting.7 The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Conference on Practice Improvement (December 2015, Dallas, Tx.), provided tours of the Primary Care Office of the Future. These model rooms were originally developed by the Connecticut Institute for Primary Care Innovation and that, among other innovations emphasized the importance of sharing information with patients during the visit using large flat-panel screens. Use of these innovations foster productive inter-professional teamwork around a patient or population.8

Discussion

The patient’s chart is a critically important tool in patient care. This is as true in the digital world today as it was in the paper world of yesteryear. Practice to practice variability in paper chart organization and use was nearly as great as practice to practice variability in EMR implementations, even of the same vendor, due to local customization.

These skills and familiarity with localization is as important for physicians today as skill with any other medical procedure or instrumentation. Physicians who are skilled at navigating and locating patient’s information are more productive than those who have difficulty locating that information.9 On the other hand, when the physician’s computer skills are less than adequate, demanding heavy use of the computer by the physician is viewed negatively by the patients.10 McGrath, et al. emphasized the importance of physician training noting that those who are skilled at using the equipment AND have the ability to use that equipment in the context of a patient visit are more productive than those who have difficulties with these skills. This competency can have a positive effect on patient health.

Enhanced patient engagement is important for disease management and optimized physician-patient communication is key in this process.11 The physician’s skill and understanding of these tools is the primary influencer, both positively and negatively, in the nonverbal communication between the physician and the patient. Understanding of the hardware features and functions and being able to adapt to new technologies is as important for the office physician as skill and dexterity with surgical instruments is to the surgeon. Being able to incorporate multiple screens, manage multimedia, incorporate mobile and patient generated data, and how to extract and share information with the patient without disrupting the visit requires not only knowledge but practice.

The nonverbal framework for the interview is often dictated by the spatial arrangement of the patient, computer and physician. This framework can dictate a closed, blocked or open nonverbal communication. McGrath postulated the ideal arrangement was where the computer and patient are both positioned in a 45-degree angle toward the physician.12

Most family medicine residency programs are ill equipped to provide effective training in how to function in rooms much more optimized from a technology perspective. This is particularly true of our program, Community and Family Medicine at Truman Medical Center – Lakewood. Our residents practice in rooms that are ill designed for computers. The placement of computers often present barriers residents and faculty need to overcome in order to be able to effectively use them during the patient encounter. Some rooms have the computers built into the wall where it is impossible to use them without turning one’s back to the patient and make it difficult to share what’s on the screen with the patients (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Traditional clinic room ill designed for computers.

Other rooms are better suited and allow the physician and patient to sit where both can easily visualize the screen as well as interact together comfortably in a triangular where the patient, physician and computer are points in an equilateral triangle (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Exam room with consultation table.

The rooms were designed long before computers became an integral part of the visit work flow. Modern exam rooms, such as those designed by MidMark Solutions,13 (See Figure 3), are configured to facilitate both a consultation area facilitating this triangle.

Figure 3.

Examples of exam rooms designed with computer in mind

©2012 Midmark Coporation. All images are the sole property of Midmark Corporation and cannot be reproduced. Manufactured and/or distributed by Midmark Corporation, Versallies, OH.

An extreme form of this design is being used in large company on-site clinics, such as Cerner’s Healthe Clinic on its World Headquarters campus in North Kansas City. These exam room suites were designed by employees planning to be patients at this clinic (Figure 4) and in these the exam area was separated from the consultation area to facilitate parents bringing their children in as a family unit for their visits.

Our residency programs facility, like many primary care offices, cannot retrofit all of our exam rooms with adequate devices to enhance the exam room experience. To ameliorate this deficiency and provide better tools for our residents, we have opted to arm our residents with state-of-the art mobile devices that help overcome some of the existing barriers.14 This allows us to expand our education to include patient-physician-computer interactions that are necessary to practice medicine. In this way we are training our residents to be able to adapt to virtually any environment in which they find themselves as well as encouraging them utilize best practices with regard to using the computer in the exam room to improve the patient experience and engender patient engagement in their health.15

We are also undertaking a year-long process improvement project lead by Dr. Beth Rosemergy, Medical Director of the resident run Family Medicine Clinic. In this project all first-year residents are asked to change their normal interactions with patients and incorporate the computer as the third entity in the room. Where possible faculty teach our residents how to interact with the patients using the computer as a critical visit tool in the exam room.

Teaching our residents to recognize the spatial arrangement (proxemics) of the room; helping them learn to adapt by repositioning themselves and the patient so both the can easily share (participate and interact with) what is on the computer screen better prepares them for their future careers. The residents can use their own devices or the computer in the room to actively draw the patient’s attention to the monitor throughout the interview and visit and, to complete most of their documentation in the exam room. The patient is being asked to validate the information already in the chart as well as what is being added to the chart for accuracy. After the visit a questionnaire is given to the patient asking them for their opinion and effect of this behavior.

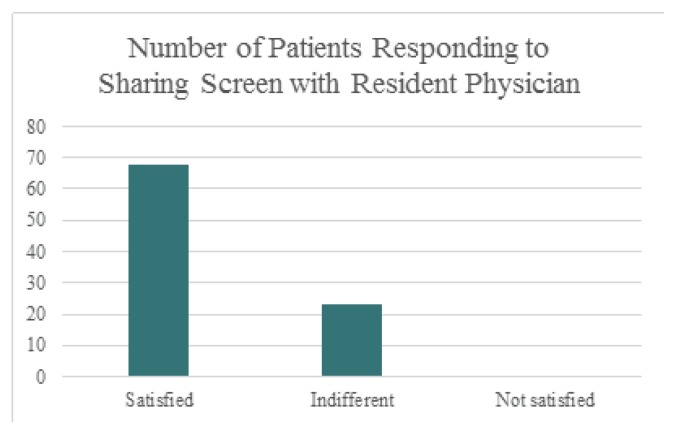

Early results (unpublished) are very encouraging (See Figure 5). Patients are reporting that they do not object to this behavior, perceive this computer use positively and that it does not detract from the physician-patient communication. The residents also report learning to do this helps them with accurate documentation, has uncovered many inconsistencies in the chart and does not slow or obstruct the normal visit experience.

Figure 5.

Patient satisfaction with residents inviting patients to share screen for problem review and medication reconciliation.

By incorporating and helping residents learn to actively use their computers with their patients we are improving their ability to increase the accuracy and completeness of the chart while increasing patient engagement. Both of these are critical physician skills as we move from a volume to value based reimbursement system where so much depends on quality measures, patient engagement, satisfaction and active participation in their health. We are confirming that simply directing the patient’s attention to the screen and inviting them to participate in the documentation is consistent with the essence of patient centered care that is so fundamental to Family Medicine.

Biography

David A. Voran, MD, (left), MSMA member since 2010, Beth Rosemergey, DO, (right), MSMA member since 2015, are both Assistant Professors at the Community and Family Medicine Department, University of Missouri-Kansas City and Truman Medical Center-Lakewood. Teri Scott, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC, is at Truman Medical Center, Kansas City.

Contact: vorand@umkc.edu

Footnotes

Disclosure

None reported.

References

- 1.Crampton NH, Reis S, Shachak A. Computers in the clinical encounter: a scoping review and thematic analysis. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2016 2016 Jan 14;:1–14. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joos D, Qingxia C, Jirjis J, Johnson KB. An Electronic Meidcal Record in Primary Care: Impact on Satisfaction, Work Efficiency and Clinical Processes. AMIA - American Medical Informatics Association. 2006 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gadd CS, Penrod L. Dichotomy Between Physician’s and Patients’ Attitudes Regarding EMR Use During Outpatient Encounters. AMIA; Pittsburgh: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strayer SM, Semler MW, Kington ML, Tanabe KO. Patient Attitudes Toward Physician Use of Tablet Computers in the Exam Room. Family Medicine. 2010;42(9):643–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frankel R, Altshuler A, Sheba G, Kinsman J, Jimison H, Robertson NR, Hsu J. Effects of Exam-Room Computing on Clinician–Patient Communication A Longitudinal Qualitative Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:677–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ventures W, Kooienga S, Marlin R. EHRs in the Exam Room: Tips on Patient-Centered Care. Family Practice Management. 2006 Mar; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.http://www.med.unc.edu/csc/about/facilitiesOnline

- 8.Saint Francis Care and University of Connecticut School of Medicine. CIPCI; [Online] Available http://www.cipci.org/future. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rouf E, Whittle J, Lu N, Schwartz MD. Computers in the Exam Room: Differences in Physician–Patient Interaction May Be Due to Physician Experience. Society of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:43–48. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0112-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ratanawongsa N, Barton JL, Lyles CR, Wu M, Yelin EH, Martinez D, Schillinger D. ssociation Between Clinician Computer Use and Communication With Patients in Safety-Net Clinics. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015 Nov 30; doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coutler A. Patient Engagement - What Works? Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2012;35(2):80–89. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e318249e0fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGrath JM, Arar NH, Pugh JA. The influence of electronic medical record usage on nonverbal communication in the medical interview. Health Informatics Journal. 2007;13(2):105–118. doi: 10.1177/1460458207076466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MidMark Solutions. Midmark International. Available: http://www.midmark.com/

- 14.David Voran M. David Voran’s Blog. May 7, 2015. Available: https://vorand1125.wordpress.com/2015/05/07/technology-fund-for-familymedicine-residents/

- 15.Joos D, Chen Q, Jirjis J, Johnson KB. An Electronic Medical Record in Primary Care: Impact on Satisfaction, Work Efficiency and Clinic Processes. AMIA Proceedings. 2006 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]