Abstract

The aim of this review is to assess the effectiveness of reentry programs designed to reduce recidivism and ensure successful reintegration among adult, male offenders. Studies were included if they (a) evaluated a reentry program incorporating elements dealing with the transition from prison to community for adult, male offenders; (b) utilized a randomized controlled design; and (c) measured recidivism as a primary outcome. In addition, secondary outcomes measures of reintegration were also included. The systematic search of 8,179 titles revealed nine randomized controlled evaluations that fulfilled eligibility criteria. The random-effects meta-analysis for rearrest revealed a statistically nonsignificant effect favoring the intervention (odds ratio [OR] = 0.89, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.74, 1.07]). Similar results were found for reconviction (OR = 0.94, 95% CI [0.77, 1.12]) and reincarceration (OR = 0.90, 95% CI [0.78, 1.05]). Studies reported mixed results of secondary outcomes of reintegration. The results of this review reflect the variability of findings on reducing recidivism. The challenges faced in conducting this review highlight a need for further research and theory development around reentry programs.

Keywords: interventions, meta-analysis, reentry, randomized controlled trial, recidivism, systematic review

Introduction

In the United States, 93% of prisoners will at some point return to their communities. Therefore, it is important to look at the process by which they readjust into life outside prison walls (Petersilia, 2003). In addition, issues such as the great number of released prisoners, the high recidivism rates, and the economic burden of the prison system warrant attention to the reentry process (Duwe, 2012). Furthermore, it has been evident that many inmates enter prison with major social and personal problems, ranging from financial insecurity, unemployment, substance use, mental health, and poor social relationships. Not only will they encounter the same problems when they leave, but they also leave prison with new problems (loss of a house, job, and/or relationship) (Maguire, 2007). This begs attention for reentry efforts in criminology and intervention research.

Reentry interventions can be correctional-based, community-based, or both (Duwe, 2012; Seiter & Kadela, 2003). These programs can vary in terms of complexity: Some are unimodal meaning they target one aspect of reentry (e.g., substance use), whereas others are multimodal meaning they target several aspects of reentry (e.g., employment, housing, social support, and substance use). Although they can take many forms, reentry programs should focus on the transition from prison to the community to maximize reintegration (Bouffard & Bergeron, 2007). Ideally, these programs would also make this transition a gradual one (Petersilia, 2003). To do this, many reentry programs have several phases; firstly, within the walls of the prison, then into the community, and finally, integration where independence is encouraged (Day, Ward, & Shirley, 2011; Taxman, Young, & Bryne, 2004). Reentry programs tend to be relatively short because the risk of recidivism is highest during the first year after release (Langan & Levin, 2002).

Many scholars have argued that one of the greatest weaknesses in reentry literature is the lack of theory (Maloney, Bazemore, & Hudson, 2001; Maruna, Immarigeon, & LeBel, 2004). Most reentry interventions have a “rather bizarre assumption that supervision and some guidance can steer the offender straight” (Maloney et al., 2001, p. 24). Moreover, most reentry interventions use a deficit-based approach, in which programs aim to correct the deficits that offenders have in order to be successful (Schlager, 2013). Indeed, most reentry interventions focus on human and social capital via helping with employment, housing, increasing social support, and lowering dependency on drugs and alcohol. Although much of the literature and studies on developed interventions do not clearly state a theory of change, many implicit theories can be found. Several criminological theories can be used to explain why improvements in these areas may decrease the likelihood of recidivism. For example, employment has been seen as a resiliency factor because it has economic and cognitive benefits; it ketif people from perpetrating crimes (Krienert & Fleisher, 2004). Considering social support, social bond theory argues that strong bonds to family and friends will restrain people from becoming involved in illegal activities (Colvin, Cullen, & Vander Ven, 2002). However, by focusing on the deficits of offenders, the strengths, capabilities, and agency to engage in the reentry process have largely been ignored. Reentry is a process and not a finite event. Therefore, Schlager (2013) argues for a new narrative in reentry, namely, a strengths-based approach. This approach focuses on the strengths of offenders and engages them in the process of reentry. In this approach, three key principles for successful offender reentry are highlighted: officer–offender relationship, empowerment of offenders to change, and cooperation from the community (Schlager, 2018). Through the first principle, law-abiding behavior is promoted in the offender–officer relationship. In addition, empowered offenders are more likely to engage and be motivated to reach their reentry goals. Finally, cooperation with the community allows for inclusion and redemption in the reentry process. In this way, prosocial beliefs are promoted, and offenders are provided with activities which support offender reentry and are surrounded by a cooperative community, therefore increasing their chances of success in their reentry.

Despite the attention reentry interventions have received, few reviews have been conducted. Seiter and Kadela (2003) conducted a review on five different types of reentry programs and found four of the five to be effective in reducing recidivism (vocational/work release programs, drug rehabilitation, halfway houses, and prerelease programs). Although their review was useful in detailing the various available programs, it was not a systematic review and it is now outdated. A systematic review of the effectiveness of reentry programs for women is currently under review (Heidemann, Soydan, & Xie, under review). Preliminary results, received through contact with the first author, suggest no significant effects on recidivism for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of women’s reentry programs. They did however find positive, significant effects in nonrandomized trials with an overall effect size of odds ratio (OR) = 0.59 (95% CI [0.44, 0.78]). A few systematic reviews have considered specific subsets of reentry programs (Miller & Ngugi, 2009; Newton et al., 2018; Visher, Winterfield, & Coggeshall, 2006), respectively on noncustodial employment programs, vocational education and training programs, and housing schemes. To date, the impacts of social support and substance use on measures of successful reentry have not been systematically reviewed. In addition, multimodal programs have yet to be included in a systematic review.

The bulk of the trials of reentry programs utilize a quasi-experimental design. Recently, however, some high-quality RCTs have been conducted (Clark, 2015; Duwe, 2014; Grommon, Davidson, & Bynum, 2013; Jacobs, 2012). Such trials have yet to be systematically reviewed. A systematic review of reentry programs is particularly warranted as it can have important implications for research, policy, and practice; therefore, it is a significant step for development of this field.

Method

The main objective of this study is to examine the experimental state of evidence for reentry programs and its effects on recidivism and elements of reintegration. The evidence presented thus far on reentry interventions will be examined through the use of a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Studies included in this review were evaluated using four eligibility criteria concerning the evaluation design, target population, intervention, and outcome measure. The first criterion was that studies conducted an RCTs. This design is often referred to as the “gold standard” as it has robust internal validity and arguably, best tells whether an intervention effect is due to the intervention (Macdonald, 2000). The randomization process allows for the removal of suspicion of systematic biases in the trial (Weisburd, 2010). Although some research suggests that quasi-experimental designs can produce similar results as RCTs, these comparisons have not yet been made in criminological interventions (Weisburd, 2010). One such study compared results from high-quality nonrandomized studies with randomized experiments and found that the results significantly differed, with “weaker” designs being more likely to favor treatment (Weisburd, Lum, & Petrosino, 2001). Due to this knowledge and known existence of RCTs in reentry evaluations, only RCTs will be considered in this review. The target population of this review is formerly incarcerated adult males, defined as age 18 years or older at the time of release. The interventions investigated in this review aim to reduce barriers to reentry and aid male ex-offenders in reintegrating back to the community. They do so by providing assistance with employment, housing, social support, and/or substance use. Programs included in this review must provide assistance in at least one of these areas. The comparison could be “traditional/normal parole services,” “wait list,” or “no treatment.” Finally, the primary outcome measure of interest is recidivism. All included studies must have at least one of these measurements of recidivism: rearrest, reconviction, and reincarceration . In addition, secondary outcomes including housing, employment, substance use, and social support will be considered.

To locate unpublished and published studies, a variety of sources and strategies were utilized (electronic databases, government reports, conference papers). A full list of the databases and the keywords used to search them are reported in the appendix. All searches were conducted on May 21, 2014, and updated on March 3, 2016. In addition, two relevant journals were hand searched: the Journal of Offender Rehabilitation and the Journal of Experimental Criminology. For both journals, articles published in the past 7 years were examined. Finally, relevant experts in the field were contacted to see whether they knew of any unpublished or ongoing trials of reentry programs.

To extract the data, a standardized data extraction sheet was developed, using the Cochrane Collaboration’s data collection form for intervention reviews: RCTs only (Version 3, April 2014). The author can be contacted for the data extraction form. The Cochrane Collaboration’s “Risk of Bias” tool (Higgins & Green, 2011) was included in this form. This tool examines the following risks of bias: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detention bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), and selective reporting (reporting bias). Each potential bias is assessed and rated as “low,” “high,” or “unclear.”

To estimate the overall effectiveness of reentry programs on recidivism, a random-effects meta-analysis was deemed most fitting. Effect sizes were included as odd ratios. In the case of multiple follow-up periods, preference was given to the longest follow-up period. To increase the comparability of the results, preference was given to measures of recidivism from official statistics. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Q and I2 statistics. Q estimates the total observed study-to-study variation. The I2 statistic describes the proportion of variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Deeks, Higgins, & Altman, 2011). Due to the limited amount of data reported on secondary outcomes, the results will only be presented in a narrative synthesis.

Results

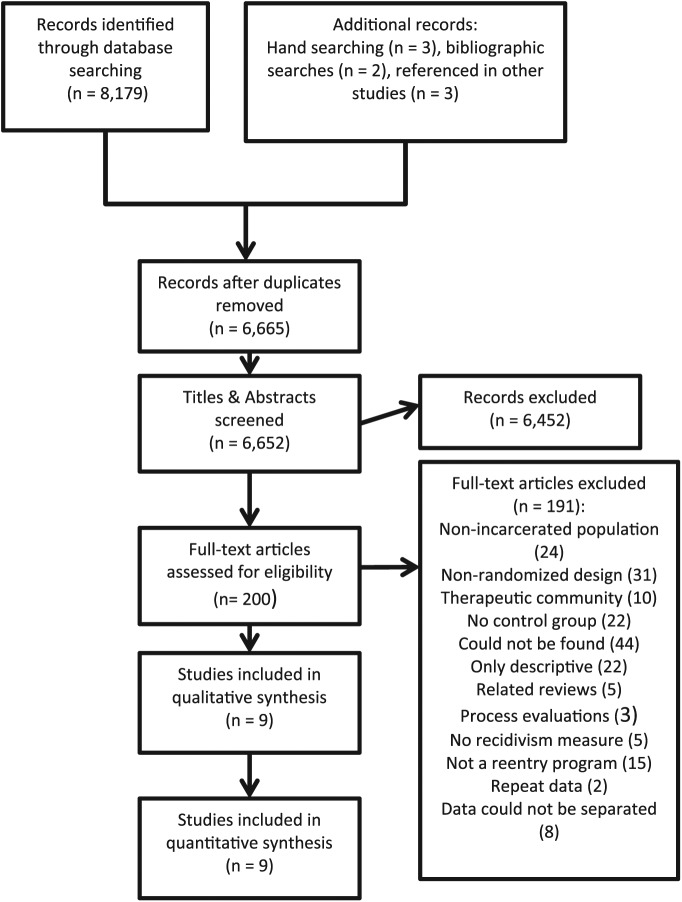

After completing all database searches, 8,179 studies were found; additionally eight were found through hand searching, bibliographic searches, and through other studies. After deduplication and screening of titles and abstracts, 200 possibly relevant articles remained. All available studies (n = 156) were examined and ultimately, nine studies were found which fit the inclusion criteria. For more details of the flow of the search, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart.

Study Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the eligible studies. The nine studies were conducted over a span of 30 years, with the first study being conducted in 1977 (Waldo & Chiricos, 1977) and the most recent in 2015 (Clark, 2015). Six of the nine studies were published in academic journals, two were government reports, and one was a PhD dissertation.

Table 1.

Summary of Studies Included in the Review.

| Citation | Design | Intervention | Sample & setting | Primary outcome measures | Secondary outcomes measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Clark, 2015

[Journal article] |

RCT Comparison: treatment as usual |

High-Risk Revocation Reduction (HRRR) Program Begins 60 days prior to release and lasts up to 1 year post-release Supplemental case planning and various services, including transitional housing, subsidized employment, mentoring, etc. |

Release violators from a Minnesota state prison Sample size: N = 239 (nExp = 162; nCon = 77) Mean age: Exp = 36.4; Con = 36.0 |

Recidivism: Rearrest, reconviction, & reincarceration |

— |

|

Davis, 2011

[PhD dissertation] |

RCT Comparison: routine postrelease services |

Support Matters 10 sessions of network therapy provided within 3 weeks of release |

Male offenders from North Carolina with lifetime history of substance use disorder Sample size: N = 40 (nExp = 20; nCon = 20) Mean age: Exp = 33.3; Con = 25.9 |

Recidivism: Rearrest |

Social support Substance use |

|

Duwe, 2014

[Journal article] |

RCT Comparison: treatment as usual |

Minnesota Comprehensive Offender Reentry Plan (MCORP) Motivational interviewing and SMART planning with services including employment, housing, mentoring, income support, substance use |

Offenders from seven prisons in Minnesota Sample size: N = 641 (nExp = 394; nCon = 247) Mean age: Exp = 36.9; Con = 32.6 |

Recidivism: Rearrest, reconviction & reincarceration |

Employment Housing Social support |

|

Employment project, 1980

[Journal article] |

RCT Comparison: normal services |

Vocational Counseling and Placement Service (VCPS) Weekly counselor sessions and 6 weekly sessions in lifestyle counseling After release: counselor via phone conversations |

Offenders in maximum security institution in Philadelphia Sample I size: N = 197 (nExp = 140; nCon = 57) Sample II size: N = 170 (nExp = 122; nCon = 48) Mean age: average slightly over 30 (not specified) |

Recidivism: Rearrest |

Employment Social integration |

|

Grommon et al., 2013

[Journal article] |

RCT Comparison: Treatment as usual |

Multimodal Community-Based Reentry Program 2 phases with counseling in a secure transitional facility + group/family treatment |

At-risk male offenders soon to be released from prison with substance dependencies Sample size: N = 511 (nExp = 262; nCon = 248) Mean age: Exp = 35.57; Con = 33.73 |

Recidivism: Rearrest & reincarceration |

Drug relapse |

|

Jacobs, 2012

[Government report] |

RCT Comparison: regular services |

Transitional Jobs Program Provided temporary, minimum-wage job and job assistance |

Recently released prisoners in the community of 4 U.S. cities Sample size: N = 1,813 (nExp = 912; nCon = 901) Mean age: Exp = 34.8; Con = 34.5 |

Recidivism: Rearrest, reconviction & reincarceration |

Employment |

|

Minnesota Department of Corrections [MDOC], 2006

[Government report] |

Quasi-RCT Comparison: treatment as usual |

Serious Offender Accountability Restoration (SOAR) Project Three phases: assessment (3 weeks), reentry preparation (90 days before release), release phase (duration unclear) Strengths-based case planning, housing assistance, community resource development, financial support |

Prisoners from one county in Minnesota Sample size: N = 475 (nExp = 347; nCon = 128) Mean age: Exp = 26.9; Con = 27.7 |

Recidivism: Reconviction & reincarceration |

— |

|

Turner & Petersilia, 1996

[Journal article] |

Quasi-RCT Comparison: waiting list |

Work release program In-depth case management Duration: 4 months |

Offenders with minimum security status and have less than 2 years to serve Sample size: N = 218 (nExp = 112; nCon = 106) Mean age: Exp = 30.4; Con = 31.4 |

Recidivism: Rearrest |

— |

|

Waldo & Chiricos, 1977

[Journal article] |

RCT Comparison: normal parole conditions |

Work release program Program lasted from 2 to 6 months |

Inmates from prisons in Florida Sample size: N = 281 (nExp = 188; nCon = 93) Mean age: not significantly different (no data specified) |

Recidivism: Rearrest, reconviction & reincarceration |

— |

Note. RCT = randomized controlled trials; SMART = Small, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Timely.

Sample Size and Sociodemographic Information

There was considerable variability in the overall sample size, ranging from 40 (Davis, 2011) to 1,813 (Jacobs, 2012). It is important to note that the Employment Project (1980) utilized two different samples of offenders: those who started it in the first year that Vocational Counseling and Placement Service (VCPS) was offered (Sample I) and those who started VCPS after it was running for 1 year (Sample II). Therefore, the samples will be analyzed separately in the meta-analyses, noted respectively as Employment Project 1980a and 1980b.

Eight of the nine studies reported relevant demographic characteristics of the participants (Clark, 2015; Davis, 2011; Duwe, 2014; Employment Project, 1980; Grommon et al., 2013; Jacobs, 2012; Minnesota Department of Corrections [MDOC], 2006; Turner & Petersilia, 1996). Participants of all nine studies were men and the average age was 30 years. The samples were predominantly non-White, namely, African Americans; the only exception being the study of Turner and Petersilia (1996) where more than half of the sample were White. Most participants had prior prison records. Property and drug crimes were the most common committed offenses across the studies; however, a wide range of offenses were represented, including homicide, sex offenses, and violent crimes. On average, around 30% to 51% had completed a high school level of education. A similar percentage (25%-53%) was employed prior to incarceration. Three studies also had a significant number of participants with a drug and/or alcohol dependence (Davis, 2011; Grommon et al., 2013; Turner and Petersilia, 1996).

Research Setting and Geographic Location

All of the studies, with exception of Jacobs (2012), were conducted in a correctional facility, generally described as a state prison (Clark, 2015; Davis, 2011; Duwe, 2014; Grommon et al., 2013; MDOC, 2006; Waldo & Chiricos, 1977). Two studies stated more specifically that the research took place in minimum security facilities (Turner & Petersilia, 1996) or maximum security prison (Employment Research Project, 1980). The Transitional Jobs Program study took place after offenders were already released in the community (Jacobs, 2012). All of the studies were conducted in various U.S. states.

Interventions

The interventions included in this review were both unimodal (k = 5) and multi-modal (k = 4). Four of the unimodal interventions focused on work and employment related issues. Two of these four were work release programs, respectively in Florida (Waldo & Chiricos, 1977) and Washington (Turner & Petersilia, 1996). The Transitional Jobs Program offered temporary paid jobs, support services, and job placements for ex-offenders in four major U.S. cities (Jacobs, 2012). The Employment Research Project (1980), however, provided vocational counseling for offenders both pre- and post-release. One unimodal intervention, Support Matters, focused on social support, social cognitions, and behavior. This post-release intervention provided network therapy to help former prisoners connect to positive social support (Davis, 2011).

Four interventions were multimodal, meaning they focused on several aspects of the reentry process (Serious Offender Accountability Restoration [SOAR] Project, MDOC, 2006; Minnesota Comprehensive Offender Reentry Plan [MCORP], Duwe, 2014; High-Risk Revocation Reduction [HRRR] Program, Clark, 2015; Multimodal Community-Based Reentry Program, Grommon et al., 2013). These interventions tended to have several phases (ranging from two to three) and focused on the continuity of care. All four multimodal interventions started prior to release and after release offered services ranging from housing, subsidized employment, mentoring, drug treatment, and so forth.

Several of the interventions were unclear about how long services were offered (Davis, 2011; Duwe, 2014; Employment Research Project, 1980; Grommon et al., 2013; Jacobs, 2012; MDOC, 2006). The two work release interventions lasted from 2 to 6 months after release (Turner & Petersilia, 1996; Waldo & Chiricos, 1977). The HRRR program lasted from 6 months up to a year after release (Clark, 2015).

Outcome Measures

Recidivism measures were given for all nine studies; all but one of the studies (MDOC, 2006) reported rearrest measures. Seven studies reported reconviction measures and six reported reincarceration measures. Over half of the studies (n = 6) measured recidivism through official statistics only, while the other three studies used a combination of self-report and official statistics. Follow-up period ranged from 7 months after release from prison up to 2 years following release.

Research Design and Comparison Conditions

All nine studies reported explicitly that participants had been randomly assigned to either treatment or control group. The procedures for random assignment differed from study to study, ranging from using a lottery system (Grommon et al., 2013) to drawing envelopes (Davis, 2011) to calling an organization for the random assignment (Turner & Petersilia, 1996). Four of the studies did not detail how they assigned participants (Duwe, 2014; Jacobs, 2012; MDOC, 2006; Waldo & Chiricos, 1977).

Two studies used a “quasi-RCT” design (MDOC, 2006; Turner & Petersilia, 1996). Because the flow of inmates was too slow to form a large enough sample in the allotted time, Turner and Petersilia (1996) chose 93 of the total 218 as a matched comparison group. The authors tested whether any differences existed between the two groups at baseline. They found that nonrandom offenders had fewer prior arrest and fewer prior parole revocations than randomly assigned offenders; however, they did not differ significantly with regard to age, race, current offense, length of prison term, multiple measures of prior criminal record, and legal financial obligations. For reasons similar to those presented by Turner and Petersilia (1996), the multifaceted reentry intervention from the MDOC (2006) was evaluated through a quasi-RCT. More specifically, for 9 months of the 21-month long allocation phase, offenders were not randomly allocated to intervention or control. The researchers tested whether any differences existed between the two groups at baseline. They found that the two groups significantly differed on several measures of criminal history, with those participating in the SOAR project having more extensive criminal histories. Because criminal history is a significant predictor of future offending, the researchers suggested that this difference between the intervention and control group may have affected the results (MDOC, 2006).

Comparison conditions differed nominally among the studies. Three studies utilized treatment as usual comparison group (Clark, 2015; Duwe, 2014; Grommon et al., 2013; MDOC, 2006). Three studies compared the intervention with those who received routine postrelease services (Davis, 2011; Employment Research Project, 1980; Jacobs, 2012). Turner and Petersilia (1996) used waitlist controls and Waldo and Chiricos (1977) compared participants with those who received normal parole conditions.

Risk of Bias Appraisal

The methodological quality of the included studies was variable (see Table 2). None of the nine studies included information for all six categories of the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (Higgins & Green, 2011). Five out of the nine studies reported how the random sequence was generated, all of which met the criteria for “low risk of bias.” As it was unclear how the random sequence was generated for the remaining four studies, they were given an unclear risk of bias. Allocation concealment was explicitly noted in three studies (Davis, 2011; Employment Project, 1980; Turner & Petersilia, 1996). As these studies utilized methods to lower the chances of selection bias (through, for example, calling a third party to receive an offender’s assignment), these studies met the criteria for “low risk of bias.” Due to the ambiguity of the remaining studies on allocation concealment, these studies were given an unclear risk of bias. Two studies provided information regarding blinding of participants and personnel (Davis, 2011; Grommon et al., 2013). Grommon et al. (2013) reported that parole board members and agents were blind to the assignment and therefore received a low risk of bias. Davis (2011) reported that the personnel who conducted randomization were blind to preintervention characteristics between groups and therefore also met criteria for low risk of bias. Due to the lack of information in the remaining seven studies, an unclear risk of bias was given. Only one study (Waldo & Chiricos, 1977) reported blinding assessors. It is often very difficult to blind participants and personnel; however, blinding assessors should be possible albeit with adequate resources. Four studies failed to report data on attrition (Grommon et al., 2013; Jacobs, 2012; MDOC, 2006; Turner & Petersilia, 1996). Of the studies that did report on incomplete data (k = 5), the attrition rate ranged from 13% (Employment Project, 1980) to 24% (Clark, 2015) to 57% (Duwe, 2014) for experimental groups and from 1% (Clark, 2015) to 4% (Davis, 2011) to 57% (Duwe, 2014) for control groups. These studies reported various reasons for dropout, including returning to counties not included in the project, program was not fitting the needs of the offenders, too short of stay, and so forth (Clark, 2015; Davis, 2011; Duwe, 2014; Employment Project, 1980). Although attrition rates were unclear in the study from Waldo and Chiricos (1977), various sample sizes were noted across different analyses, which suggests that available case analyses were conducted rather than full intent-to-treat analyses. This study, therefore, received a high risk of bias on incomplete outcome data. None of the nine included studies made clear reference to a protocol, which means there was no way to determine whether decisions had been made a priori. This can result in reporting bias; hence, all studies were given an unclear risk of bias on selective reporting.

Table 2.

Risk of Bias Summary.

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clark, 2015 | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | ? |

| Davis, 2011 | + | + | + | ? | + | ? |

| Duwe, 2014 | ? | ? | ? | ? | – | ? |

| Employment project,1980 | + | + | ? | ? | + | ? |

| Grommon et al., 2013 | + | ? | + | ? | ? | ? |

| Jacobs, 2012 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| MDOC, 2006 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Turner & Petersilia, 1996 | ? | + | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Waldo & Chiricos, 1977 | ? | ? | ? | + | – | ? |

Note. + = Low risk of bias; ? = unclear risk of bias; – = high risk of bias.

Effects of Reentry Programs on Recidivism: Meta-Analyses

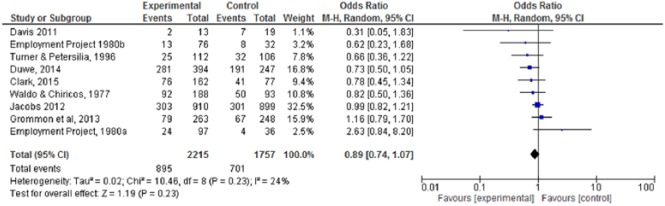

A random-effects analysis was conducted with all nine included studies. The Employment Research Project (1980) presented recidivism data for two statistically independent groups (Sample I and Sample II); hence, both were separately added to the meta-analysis. Effect sizes in the form of ORs were calculated for each study. Three separate meta-analyses were conducted for the three different measurements of recidivism. Rearrest was reported in eight studies (nine independent samples), reconviction in seven studies (eight independent samples), and reincarceration in six studies.

The forest plot for rearrest data (Figure 2) reveals a pooled effect size of OR = 0.89 (95% CI [0.74, 1.07]). In other words, overall, reentry programs reduced the relative risk of rearrest by 5% for the intervention groups. Six of the nine studies favored the experimental group; however, the confidence interval of every study included one, the point of no effect. Thus, the general trend suggests the intervention could be effective; however, none of the studies were statistically significant. This is also true for the overall pooled effect size; thus, this analysis provides no support for the hypothesis that reentry programs increase (or decrease) the odds of rearrest.

Figure 2.

Forest plot (rearrest).

Note. CI = confidence interval.

The Q statistic is nonsignificant (χ2 = 10.46, df = 8), which indicates that there is little statistical heterogeneity. The I2 is 24%, which suggests that heterogeneity is of little importance for this meta-analysis (Higgins & Green, 2011).

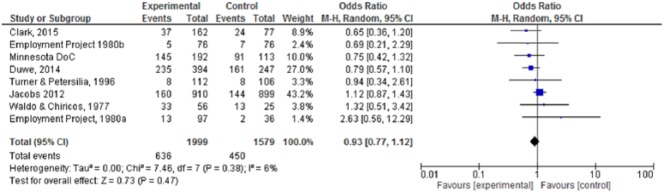

Reconviction data were also collected in seven studies (eight independent samples). Figure 3 shows the forest plot for the reconviction data. A pooled effect size was found: OR = 0.93 (95% CI [0.77, 1.12]); this implies that the intervention group was slightly less likely to be reconvicted; however, note all confidence intervals include one; this is also true of the pooled effect size. Similarly to the rearrest data, the Q statistic is not significant (χ2 = 7.46, df = 7), suggesting that heterogeneity is not a concern for these data. The I2 statistic is low (6%), implying that heterogeneity does not have an impact on the results for reconviction.

Figure 3.

Forest plot (reconviction).

Note. CI = confidence interval.

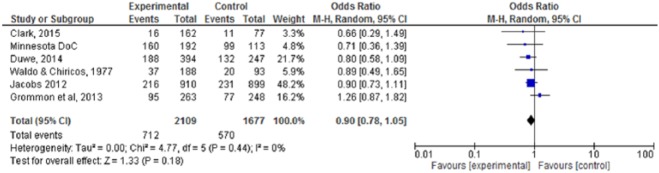

The final measure of recidivism reported in this analysis is reincarceration. Six of the nine studies measured reincarceration. The forest plot of the reincarceration data can be found in Figure 4. The overall effect size is OR = 0.90 (0.78, 1.05). This estimate insinuates that the intervention and control group had similar odds of being reincarcerated. Again, the Q statistic is nonsignificant (χ2 = 4.77, df = 5) and an I2 of 0% has been computed, which alludes that the heterogeneity is through random error, that is, all observed variance is spurious. It is important to note, this does not necessarily mean that heterogeneity does not exist but rather there is not enough evidence to detect it.

Figure 4.

Forest plot (reincarceration).

Note. CI = confidence interval.

Secondary Outcomes

In the included studies, three studies reported on employment outcomes (Duwe, 2014; Employment Project, 1980; Jacobs, 2012), one reported on housing (Duwe, 2014), three reported on social support (Davis, 2011; Duwe, 2014; Employment Project, 1980), and two reported on substance use (Davis, 2011; Grommon et al., 2013).

With regard to employment, those who participated in the Transitional Jobs Program saw increased employment early in the study (at 1-year follow-up), but gains faded as they left the program. At the 2-year follow-up, the intervention group was not any more likely than the control to be employed (Jacobs, 2012). The Employment Research Project (1980) also did not find significant differences between the groups when postrelease employment was measured. Duwe (2014), however, found that participating in MCORP significantly increased an offender’s odds of accessing employment.

Duwe (2014) also considered the effects of MCORP on housing. He considered housing issues in three ways: adequacy (homelessness), stability (multiple residences), and neighborhood context (crime rates of communities). With regard to adequacy, participants of MCORP had an increased odds of acquiring housing (i.e., not homeless). Those in the intervention group did, however, report living in more than one resident more often than those in the control group (54.1% vs. 35.4%). This difference was also significant (χ2 = 9.73, df = 248, p < .01). The crime rates of the location where the offender lived, however, did not significantly differ between the groups (Duwe, 2014).

With regard to effects on social support, Support Matters participants reported an increase in tangible social support over time, whereas controls experienced a decrease in support over the 6 to 7 months following release from prison (Davis, 2011). Similarly, Duwe (2014) reported that participants in MCORP had a broader social support system post-release in comparison to the control group. The researchers from the Employment Research Project (1980) considered social adjustment, defined as a reduction of daily problems including finding place to live, drug problems, and so forth, and found no significant differences between the groups.

Davis (2011) also considered the effects of Support Matters on substance use. No significant differences were found between intervention and control groups concerning the amount of use for each substance or the frequency of use. Grommon et al. (2013) looked more specifically at drug relapse. They found, in a 2-year follow-up period, that 71% of the control group relapsed in comparison to 75% of the treatment group. The differences were, however, not statistically significant (Grommon et al., 2013).

Discussion

This systematic review considered nine different reentry programs which had been evaluated through an RCT. These reentry programs ranged from focusing on employment (work release, transitional jobs, vocational counseling, and placement) to social support to targeting multiple aspects of reentry. All the included trials were done in the United States with male participants. All but one trial consisted of predominately African American offenders, with the average offender being 30 years old. The nine included trials were meta-analyzed to consider the overall effect size of reentry programs on three measures of recidivism. The results of the meta-analyses were not encouraging. Although rearrest seems to favor the intervention, it was not significant (OR = 0.89; 95% CI [0.74, 1.07]). Similar results were found for reconviction (OR = 0.93; 95% CI [0.77, 1.12]) and reincarceration (OR = 0.90; 95% CI [0.78, 1.05]). It is noteworthy that concerning reconviction, three studies favored controls, although they were not statistically significant (Employment Project, 1980a; Jacobs, 2012; Waldo & Chiricos, 1977). This is also true for Grommon et al. (2013) with regard to reincarceration. These results suggest that current reentry programs have no significant effects on reducing or increasing odds of recidivism for adult, male offenders.

Secondary outcomes were limitedly reported in the included studies. Only five of the nine studies had a “reintegration” measurement (employment, housing, substance use, and social support; Davis, 2011; Duwe, 2014; Employment Research Project, 1980; Grommon et al., 2013; Jacobs, 2012). Many of the programs targeted at least one of these variables; however, they were not measured. This information would have been fruitful in consideration of the debate within reentry literature as to whether recidivism is the best measure of program success. The critiques concerning recidivism reveal it is a limited measure because (a) it is only one outcome of a process which demands many changes from offenders and (b) that recidivism measures capture not only individual reoffending behavior but also the decision making of the criminal justice system (Wright & Cesar, 2013). Although these arguments are valid, the reintegration data provided in this review had similar findings as the primary outcome recidivism. In the case of the six studies which did report changes in employment, housing, social support, and substance use, mixed results were found. Results concerning employment and substance use were nonsignificant, with the exception of Duwe (2014) who found that participants of MCORP had higher odds of accessing employment in comparison to the control group. Duwe (2014) also found significant differences in housing in terms of adequacy and stability. Although the intervention group was less likely to be homeless, they did report having more unstable housing (i.e., multiple residences) than control. Two studies considered the effects of the reentry programs on social support and found that participants experienced an increase of tangible support and had a broader support network in comparison to controls (Davis, 2011; Duwe, 2014). Due to the limited information provided, the results should be interpreted cautiously.

There are also some important considerations with regard to generalizability. As previously mentioned, many of the samples used in these trials were non-Whites. Although the reentry literature does not greatly discuss differences between ethnic groups, previous research on people leaving jail found differences between ethnic groups concerning patterns of drug use, health problems, and priority needs, suggesting that different intervention priorities may be necessary for different ethnic groups (Freudenberg, Moseley, Labriola, Daniels, & Murrill, 2007). This could imply that the findings may only be applicable to African American male offenders. This highlights an important point for future work in reentry research: There is a need for more subgroup analyses. Such analyses help answer the question what works for whom and under which circumstances (Hinshaw, 2002). These questions are extremely important not only for the development of reentry programs but also to help tailor them to offenders.

Furthermore, all of these trials took place in several different states in the United States. There is evidence that states differ in their propensity to reincarcerate offenders; thus, the results may have been influenced by strict versus more lenient criminal justice policies. It would be advisable to contain the results of this review to the United States because no trials from other countries were included in this review. More rigorous evaluations are needed in European countries in particular, because the consequences of reentry are arguably more pressing due to the higher number of short prison sentences (Webster, Hedderman, Turnball, & May, 2001).

The quality of the studies included in this review is disappointing. Although all of the studies conducted an RCT, none of the nine studies included information for all six categories of the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (Higgins & Green, 2011). This makes it difficult to judge the amount of bias in each study and to determine how such biases may have affected the results. Under such circumstances, it is advised to interpret these results cautiously. Furthermore, only four studies mentioned a process evaluation (Clark, 2015; Duwe, 2014; Grommon et al., 2013; MDOC, 2006). Process evaluations help determine whether the intervention was implemented as it was intended (Fraser, Richman, Galinsky, & Day, 2009). Such evaluations include factors associated with program implementation, such as quality of delivery, in order to measure program integrity (Andrews, 2006). These evaluations often focus on program design; however, other aspects of program integrity, including treatment engagement and treatment allocation, are also integral for determining the impact of interventions (McMurran & Ward, 2010). The four studies that did consider such elements found that varying levels of dosage were given to participants, lack of communication was present among partner agencies and stakeholders, inconsistent provision of services was presented, and a small percentage of participants actually took up the offered services. Thus, it appears that these four programs were not able to sustain program integrity because the reentry programs were not implemented as intended. This affects the results and their generalizability. Due to the general low quality of the included studies, caution should be taken in interpreting the overall results of the three meta-analyses presented.

This review may contain some biases as a result of the review process. Firstly, due to time constraints, studies were only evaluated and coded by one rater. Thus, studies may have been mistakenly excluded or information could have been incorrectly coded. Secondly, although wide search strings were used, the author only came across studies published in English. There could be other relevant trials available in other languages which may or may not coincide with the results of this review. In addition, many studies had to be excluded as the full text could not be found. This was primarily the case for government reports. These reports could have met the inclusion criteria and may have influenced the results. Finally, there is a lot of missing information with regard to the quality of the studies. Although authors of these studies were contacted, very few responses were received. Thus, incomplete reporting may result in incomplete information included in the review; this is particularly important because study quality is often used to interpret the trustworthiness of the results.

The results of this review are reflective of the variable findings in previous research. Although Seiter and Kadela (2003) report finding positive findings for four types of reentry programs, the evidence they presented was weak. The overwhelming majority of the studies they discussed used a quasi-experimental design with no attempts to match participants or control for variables. They also noted that some studies had potential selection bias through high attrition rates and low program completion. Furthermore, the conclusion reached by the authors is questionable. The narrative synthesis they provided lacked many important details. For example, they described that the results were significant but did not give an indication of an effect size. Although they concluded these four programs work, it is arguable that they should have been labeled as “promising” because very few studies were considered, most of which with questionable internal validity.

This review concurs with the findings from systematic reviews of subsets of reentry programs, such as employment programs and housing schemes. The two reviews conducted on these topics found no significant reductions in recidivism (Miller & Ngugi, 2009; Visher et al., 2006). The Campbell review of reentry programs for women also found that reentry programs did not have a significant effect on recidivism (Heidemann et al., under review). However, the authors did find a significant reduction in recidivism when programs were evaluated with nonrandomized designs. Because there is a substantial amount of trials of reentry programs for males using quasi-experimental designs, future research may want to review the evidence from such studies, noting their limitations.

Conclusion

Implications for Practice and Policy

Due to the limited number of studies and cautious conclusions reached by this review, only modest recommendations for practice and policy can be given. Although the results are not very encouraging, it is important that funding for reentry programs is supported. These programs have the potential to not only reduce recidivism but also improve day-to-day functioning for ex-offenders. It is clear that funding should be given to those programs which consider prior research and comprise of a theoretically driven model of reentry. More specifically, programs which use a strengths-based approach warrant more scholarly attention, particularly because the trials in this review which saw trends towards reductions in recidivism reflected some of the principles of the strengths-based approach. For instance, many of the trials which did see trends towards reductions in recidivism found that continuity of care is integral for a smooth transition from prison to the community (Duwe, 2014; Grommon et al., 2013; MDOC, 2006). This requires clear communication between institutional personnel and those institutions outside of prison helping with the transition, meaning both probation and community-based services. This reflects the principle of cooperation from the community (Schlager, 2013). Furthermore, although needs of offenders are the focal point of current reentry programs, they tend to focus only on short-term needs. Practitioners may also want to consider long-term opportunities for ex-offenders. This is also in line with the strengths-based approach, which argues for empowering offenders by focusing on their strengths and actively engaging them in the reentry process

Implications for Research

This review found that a number of high-quality RCTs have been conducted on reentry programs. This can only be further encouraged. Many countries have reentry programs in place; however, no rigorous evaluations could be found for countries beyond the United States, thus a call for formal evaluations of these programs should be stressed. This information can be valuable for improving current reentry practices. As Weisburd (2003) argues, researchers have a moral imperative to conduct randomized experiments; however, in practice many providers and organizations involved with intervention trials have grave misunderstandings of RCTs and can be very wary on conducting an RCT. It is therefore important that researchers attempt to build better relationships with the providers of the intervention, including Department of Corrections, probation offices, and other organizations involved. Researchers should spend more time clarifying why RCTs are important and try to debunk myths concerning implementing them. In this way, such organizations may be more willing to engage in reentry trials. Furthermore, not only should more trials be conducted, but the reporting of reentry trials could also be improved. As this review highlighted, a lot of information concerning biases, dosage, continuity of treatment, and so forth, was missing from the written evaluations of these programs. Researchers should be more meticulous in thoroughly describing the program, its content, and the procedures of the trial. In addition, many authors have used the explanation of a chasm between the program intention and implementation as the reason for small or nonexistent treatment effects. Such explanations should be validated and explored through process evaluations.

One of the main criticisms of evaluations of criminological interventions is the use of recidivism as the primary outcome. The opponents of using this outcome argue for a reintegration measure; a measure which would consider day-to-day functioning of offenders. This is an admirable suggestion; however, to date no such measure has been made. Future research ought to consider developing a standardized measure of reintegration which gives a clear depiction of what successful reintegration means.

Wright and Cesar (2013) eloquently detailed a complete model of offender reintegration. They argue that successful reentry programs should address individual-, community-, and system-level variables of reentry. Their model seems promising; however, no experimental designs have tested the utility of this model. This is also the case for the four models of resettlement put forth by Maguire (2007) and the strengths-based model by Schlager (2013). Although these models have been described and used implicitly in several reentry programs, no formal testing has been done to see which ones are most effective. The field of reentry is in need of more theoretical grounding; therefore, the explicit testing of such theories and models would be greatly beneficial.

Appendix

Table A1.

Keywords Used to Search Electronic Databases.

| Target population | m?n OR male OR adult AND Offend* OR ex-offend* OR “ex-offend*” OR former offend* OR Inmate* OR ex-inmate* OR “ex-inmate*” OR former inmate* OR Criminal* OR ex-criminal* OR “ex-criminal*” OR “former criminal*” OR Prisoner* OR ex-prisoner* OR “former prisoner*” OR Incarcerat* OR “formerly incarcerate*” OR Convict* OR ex-convic* OR “ex-convict*” OR “former convict*” OR Felon* OR ex-felon* OR “ex-felon*” OR “former felon*” OR release OR probation OR parole* OR violator OR perpetrator OR violen* OR arrest* OR offen?e |

| AND | |

| Intervention | reentry OR re-entry OR “re-entry” OR reintegrate* OR resettlement OR transition* OR resociali* OR assist* OR “aftercare” OR pre-release OR “pre-release” OR community OR halfway* OR home OR house OR employ* OR job* OR social OR family OR “substance abuse” OR alcohol OR drug OR treatment OR intervention OR post-release OR “post-release” OR “throughcare” OR “coming home” OR return OR release? OR discharge? |

| AND | |

| Evaluation design | Randomi?ed control trial OR RCT OR quasi-experiment* OR “quasi-experiment*” OR impact OR effect* OR non-randomi?ed OR “non-randomi?ed” OR “control* trial*” |

| AND | |

| Outcome | recidiv* OR re-offend* OR “re-offend*” OR desist* OR refer* OR re-incarcerat* OR “re-incarcerat*” OR re-convict* OR “re-convict*” OR re-arrest OR “re-arrest” OR “parole violation*” |

Note. OR = odds ratio.

Table A2.

Searched Databases.

| Database | Number of studies |

|---|---|

| Bibliographic databases | |

| Criminal Justice Abstracts | 157 |

| Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) | 517 |

| International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS) | 217 |

| MEDLINE | 317 |

| PsycINFO | 603 |

| Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) | 314 |

| Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) | 1,257 |

| Social Services Abstracts | 245 |

| Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness | 77 |

| National Criminal Justice Reference Services (NCJRS) Abstracts Database | 1,769 |

| Unpublished Resource Databases | |

| OpenGrey | 361 |

| ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: Social Science | 730 |

| Dissertations & Theses A&I | 849 |

| Ethos | 4 |

| Networked Digital Library of Theses & Dissertations | 762 |

| Total | 8,179 |

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Andrews D. A. (2006). Enhancing adherence to risk-need-responsivity: Making quality a matter of policy. Criminology & Public Policy, 5, 595-602. [Google Scholar]

- Bouffard J. A., Bergeron L. E. (2007). Reentry works. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 44(2-3), 1-29. [Google Scholar]

- Clark V. A. (2015). Making the most of second chances: An evaluation of Minnesota’s high-risk revocation reduction reentry program. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 11, 193-215. [Google Scholar]

- Colvin M., Cullen F. T., Vander Ven T. (2002). Coercion, social support and crime: An emerging theoretical consensus. Criminology, 40(1), 19-42. [Google Scholar]

- Davis C. P. (2011). Incorporating naturally occurring social support in interventions for former prisons with substance use disorders: A community-based randomized controlled trial (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Digital Dissertations. (UMI 3464901) [Google Scholar]

- Day A., Ward T., Shirley L. (2011). Reintegration services for long-term dangerous offenders: A case study and discussion. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 50, 66-80. [Google Scholar]

- Deeks J. J., Higgins J. P. T., Altman D. G. (2011). Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In Higgins J. P. T., Green S. (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (pp. 243-296). West Sussex, UK: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Duwe G. (2012). Evaluating the Minnesota Comprehensive Offender Reentry Plan (MCORP): Results from a randomized experiment. Justice Quarterly, 29, 347-383. [Google Scholar]

- Duwe G. (2014). A randomized experiment of a prisoner reentry program: Updated results from an evaluation of the Minnesota Comprehensive Plan (MCORP). Criminal Justice Studies, 27, 172-190. [Google Scholar]

- Employment Project. (1980). Employment research project volume I: Unemployment, crime & vocational counseling. The Prison Journal, 60, 7-64. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser M. W., Richman J. M., Galinsky M. J., Day S. H. (2009). Intervention research: Developing social programs. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N., Moseley J., Labriola M., Daniels J., Murrill C. (2007). Comparison of health and social characteristics of people leaving New York City jails by age, gender and race/ethnicity: Implications for public health interventions. Public Health Reports, 122, 733-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grommon E., Davidson I. I. W. S., Bynum T. S. (2013). A randomized trial of a multimodal community-based prisoner reentry program emphasizing substance abuse treatment. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 52, 287-309. [Google Scholar]

- Heidemann G., Soydan H., Xie B. (2010). Reentry programs for formerly incarcerated women. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P. T., Green S. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Version 5.1.0) [updated March 2011]. Cochrane Collaboration; Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw S. P. (2002). Intervention research, theoretical mechanisms, and causal processes related to externalizing behaviour patterns. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 789-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs E. (2012). Returning to work after prison: Final results from the transitional job reentry demonstration. Retrieved from http://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/full_626.pdf

- Krienert J. L., Fleisher M. S. (2004). Economic rehabilitation: A reassessment of the link between employment and crime. In Krinert J. L., Fleisher M. S. (Eds.), Crime & employment: Critical issues in crime reduction for corrections (pp. 39-56). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langan P. A., Levin D. J. (2002). Recidivism of prisoners released in 1994. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald G. (2000). Social care: Rhetoric and reality. In Davies H., Nutely S., Smith P. (Eds.), What works? Evidence-based policy and practice in public services (pp. 117-140). Bristol, UK: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire M. (2007). The resettlement of ex-prisoners. In Gelsthorpe L., Morgan R. (Eds.), Handbook of probation (pp. 398-427). Cullompton, UK: Willan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Maloney D., Bazemore G., Hudson J. (2001). The end of probation and the beginning of community justice. Perspectives, 25(3), 24-30. [Google Scholar]

- Maruna S., Immarigeon R., LeBel T. (2004). Ex-offender reintegration: Theory and practice. In Maruna S., Immarigeon R. (Eds.), After crime and punishment: Pathways to offender reintegration (pp. 3-26). Cullompton, UK: Willan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- McMurran M., Ward T. (2010). Treatment readiness, treatment engagement and behavior change. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health, 20(2), 75-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M., Ngugi I. (2009). Impacts of housing supports: Persons with mental illness and ex-offenders. Olympia: Washington State Institute for Public Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Minnesota Department of Corrections. (2006). Final report on the Serious Offender Accountability Restoration (SOAR) Project. Retrieved from https://www.leg.state.mn.us/docs/2008/other/080912.pdf

- Newton D., Day A., Giles M., Wodak J., Grffam J., Baldry E. (2018). The impact of vocational education and training programs on recidivism: a systematic review of current empirical evidence. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62, 187-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersilia J. (2003). When prisoners come home: Parole and prisoner reentry. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schlager M. D. (2013). Rethinking the reentry paradigm: A blueprint for action. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schlager M. D. (2018). Through the looking glass: Taking stock of offender reentry. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 34, 69-80. [Google Scholar]

- Seiter R., Kadela K. (2003). Prisoner reentry: What works, what does not, and what is promising. Crime & Delinquency, 49, 360-388. [Google Scholar]

- Taxman F., Young D., Bryne J. (2004). With eyes wide open: Formalizing community and social control intervention in offender reintegration programs. In Maruna S., Immarigeon R. (Eds.), After crime and punishment: Pathways to offender reintegration (pp. 233-260). Cullompton, UK: Willan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Turner S., Petersilia J. (1996). Work release in Washington: Effects on recidivism and corrections costs. The Prison Journal, 76, 138-164. [Google Scholar]

- Visher C. A., Winterfield L., Coggeshall M. B. (2006). Systematic review of non-custodial employment programs: Impact on recidivism rates of ex-offenders. In The Campbell collaboration reviews of intervention and policy evaluations. Philadelphia, PA: Campbell Collaboration; Retrieved from https://campbellcollaboration.org/library/non-custodial-employment-programmes-ex-offenders-recidivism.html [Google Scholar]

- Waldo G. P., Chiricos T. G. (1977). Work release and recidivism: An empirical evaluation of social policy. Evaluation Quarterly, 1, 87-108. [Google Scholar]

- Webster R., Hedderman C., Turnball P., May T. (2001). Building bridges to employment for prisoners (Research Study No. 226). London, England: Home Office. [Google Scholar]

- Weisburd D. (2003). Ethical practice and evaluation of interventions in crime and justice: The moral imperative for randomized trials. Evaluation Review, 27, 336-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisburd D. (2010). Justifying the use of non-experimental methods and disqualifying the use of randomized controlled trials: Challenged folklore in evaluation research in crime and justice. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 6, 209-227. [Google Scholar]

- Weisburd D., Lum C., Petrosino A. (2001). Does research design affect study outcomes in criminal justice? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 578, 50-70. [Google Scholar]

- Wright K. A., Cesar G. T. (2013). Toward a more complete model of offender reintegration: Linking the individual, community and system-level components of recidivism. Victims & Offenders, 8, 373-398. [Google Scholar]