The comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) has been well-established as the geriatrician’s procedure. The CGA is a systematic, multimodal, interprofessional approach to a complicated older patient with the intent to diagnose geriatric syndromes, develop targeted treatment plans, and improve patient outcomes with a focus on function and quality of life.5, 19 Key elements are the assessment of medical status, functional capabilities, cognitive status, and psychosocial structure and support. The best time for a CGA is while the person is still functional in order to identify risk factors for decline and disability that can be ameliorated with appropriate interventions. Parts of the CGA should be repeated over time and over several patient care visits in order to continually monitor for new geriatrics syndromes.

While the CGA is the “toolbox” of the geriatrician, the various evaluation components can be completed by any member of the interprofessional team and the care plan that is derived from the assessment results is best prepared as team. While the CGA has been shown in various settings to improve outcomes,1, 3, 5, 6, 13, 15, 17, 18, 20 it is also time-consuming, requiring two to three hours in some cases to complete. Since there are not enough geriatric providers to assess and manage all geriatric patients, it is imperative that primary care physicians and advanced practitioners, along with all members of the health care team, are equipped with tools that can quickly evaluate an older adult for geriatric syndromes.

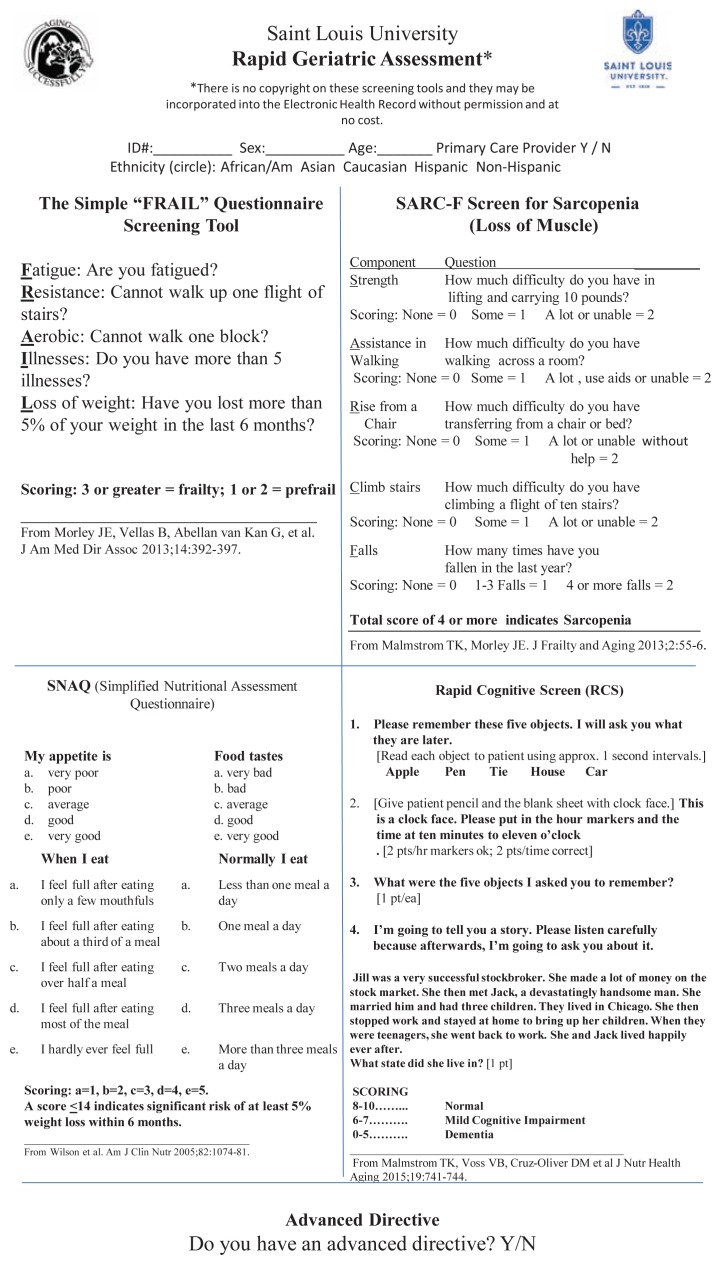

At Saint Louis University, our team created the Rapid Geriatric Assessment (RGA), which consists of four screening tools and an inquiry into the presence of advanced directives (See Figure 1). Positive responses to the RGA should trigger further assessments and management by members of the interprofessional team. Electronic versions of the RGA, training materials on its proper administration, and patient information sheets on common geriatric syndromes are available at aging.slu.edu

Figure 1.

Rapid Geriatric Assessment

The RGA consists of four short screening questionnaires: The FRAIL scale, the SARC-F scale for sarcopenia, the Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire (SNAQ), and the Rapid Cognitive Screen (RCS). These four were chosen because they can help any health care provider to quickly identify most geriatrics syndromes and none are copy written. This means that the RGA is free to use or distribute and its dissemination is encouraged. This article will briefly discuss each screening tool in turn.

Frailty

Frailty is the diminished ability to carry out important activities of daily living under stress.12 The presence of frailty predicts dementia, hospitalizations, institutionalization, falls, and fractures in community dwelling individuals.7–10 It is important to note that for many people, frailty is a pre-disabled state, and identifying frailty early helps to establish care goals and more successful interventions. If one considers the bio-psycho-social model of health care, a frail elder has limitations in these domains.

For example, the presence of multimorbid disease, bereavement, social isolation, and financial distress puts the person at risk of a significant functional decline or disability given an additional stressor, such as a new medication or illness. If one can identify and address frailty, one may delay the onset of disability, slow the progression of dependency, and improve outcomes. When an additional stressor is added, the person will not experience a permanent decompensation if the appropriate interventions are in place at the time frailty is discovered.

The ICD-10 diagnosis code for frailty is R54. The FRAIL scale is a five-item yes/no questionnaire that has been validated is several different populations around the world. Scores range from 0 to 5, with a higher score indicating more frailty. A score of zero indicates a healthy older adult, a score of 1–2 indicates pre-frail or early decline, and a score of 3 or more indicates decline and frailty. It is important that people answer the questions based on how they usually feel most of the time, not just the day of the office visit or screening tests. This applies to the following tools as well.

Sarcopenia

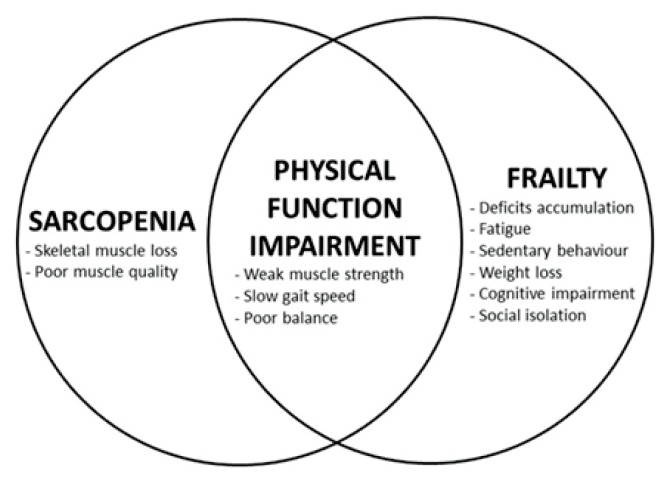

Sarcopenia is literally translated from the Greek as “the poverty of flesh” and is the decrease in both muscle mass and function that occurs with aging. Similarly to frailty, sarcopenia in the absence of functional limitations is considered a pre-disabled state, and is best assessed and treated in those who are functionally independent. While there is certainly overlap between frailty and sarcopenia, studies have determined that these are two separate clinical entities, both which can lead to poor functional outcomes4, 16 (See Figure 2). For this reason, it is important to look for both frailty and sarcopenia when assessing an older adult. The SARC-F scale has been validated in several continents and found to have good predictive ability for future dependency.2, 22 Scores range from 0 to 10 with a score of 4 or more indicating sarcopenia. Sarcopenia as a diagnosis is now billable with the new ICD-10 code M6284.

Figure 2.

Relationship among sarcopenia, frailty, and physical function impairment4.

Copyright © 2014 Cesari, Landi, Vellas, Bernabei and Marzetti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire

Significant weight loss is defined as a decrease in more than 5% of usual body weight over the last six to twelve months. Whether or not the weight loss is intentional, it may be a cause for concern in those over 65 as it contributes to memory loss, decreased immune function (predisposing to infections), decreased muscle mass and weakness, loss of function, and poor wound healing. Weight loss and cachexia are also associated with an increase in mortality in older adults. Anorexia is the main contributor to malnutrition so questionnaires that assess appetite can be useful to assess risk of weight loss and malnutrition. The Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire (SNAQ) has been validated in community-dwelling older adults, hospitalized patients, and nursing home residents and a score of 14 or less is predictive of weight loss over the following six months.14, 21 These studies also show improved functional capacity when nutritional interventions are put into place. Abnormal weight loss is billable under the ICD-10 diagnosis code R634.

Rapid Cognitive Screen

Major neurocognitive impairment (also known colloquially as dementia) is defined as memory impairment plus aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, and/or a disturbance in executive functioning. People with major neurocognitive impairment have a noticeable (although possibly subtle) decline from a previously higher level of functioning, including significant impairments in occupational or social function. Memory loss is NOT normal in older adults. It is important to distinguish dementia from mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which is memory impairment in the presence of intact activities of daily living, because early identification of a cognitive disorder allows for improved care and planning. In addition, it may be possible to reverse, prevent, or slow decline in cognition if MCI is found and treated early. It is not enough just to diagnose the presence of major neurocognitive impairment. It is also important to distinguish the various dementia syndromes (not all dementias are Alzheimer’s disease), rule out reversible causes, and provide complete bio-psychosocial care to patients and family members.

Most office-based screening instruments take 8–10 minutes to complete. For the standard primary care office visit, the length of time required to complete a short screening test is still too long. The Rapid Cognitive Screen (RCS) is the shortened version of the well-validated Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination, and is useful in a busy clinical setting. It takes roughly two minutes to complete and has been validated to pick up both major neurocognitive disorder and MCI in several languages.11 Scoring of the RCS is from 0–10. A score of 0–5 indicated dementia, 6–7 is MCI, and 8–10 is normal.

The final part of the RGA is the question, “Do you have an advanced directive?” This question is important because advanced directives are how a person communicates his desired care goals to ensure these goals are met when he is not able to express his wishes. It also gives the person administering the RGA a chance to discuss the importance of having a primary care doctor to coordinate care goals. Some web resources that may be useful for people as they document their advanced directives are:

Advance Care Planning - National Institute of Health https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/advance-care-planning

Missouri Form for Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care:

http://missourilawyershelp.org/legal-topics/durable-power-of-attorney-for-health

Goals of care discussions are also now billable under Medicare using the time-based CPT codes 99497 and 99498.

In conclusion, the components of the RGA should be viewed as routine tests given to all older adults, just like checking blood pressure. For a successful assessment, the set-up is key. Be positive as they answer and allow time if they are struggling. For any RGA done at a community screening event, provide resources and encourage them to talk to their doctors.

Biography

Milta Little, DO, is Assistant Professor and is in the Division of Geriatric Medicine and Internal Medicine, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

Contact: mlittle6@slu.edu

References

- 1.Alessi CA, Stuck AE, Aronow HU, Yuhas KE, Bula CJ, Madison R, Gold M, Segal-Gidan F, Fanello R, Rubenstein LZ, Beck JC. The Process of Care in Preventive in-Home Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:1044–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaudart C, McCloskey E, Bruyere O, Cesari M, Rolland Y, Rizzoli R, Araujo de Carvalho I, Amuthavalli Thiyagarajan J, Bautmans I, Bertiere MC, Brandi ML, Al-Daghri NM, Burlet N, Cavalier E, Cerreta F, Cherubini A, Fielding R, Gielen E, Landi F, Petermans J, Reginster JY, Visser M, Kanis J, Cooper C. Sarcopenia in Daily Practice: Assessment and Management. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:170. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0349-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caplan GA, Williams AJ, Daly B, Abraham K. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and Multidisciplinary Intervention after Discharge of Elderly from the Emergency Department--the Deed Ii Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1417–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cesari M, Landi F, Vellas B, Bernabei R, Marzetti E. Sarcopenia and Physical Frailty: Two Sides of the Same Coin. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:192. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gammack J, Paniagua MA. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. Mo Med. 2007;104:40–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerson LW, Rousseau EW, Hogan TM, Bernstein E, Kalbfleisch N. Multicenter Study of Case Finding in Elderly Emergency Department Patients. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:729–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kojima G. Frailty as a Predictor of Fractures among Community- Dwelling Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Bone. 2016;90:116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kojima G. Frailty as a Predictor of Hospitalisation among Community- Dwelling Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70:722–9. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kojima G. Frailty as a Predictor of Nursing Home Placement among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2016 doi: 10.1519/JPT.0000000000000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kojima G, Taniguchi Y, Iliffe S, Walters K. Frailty as a Predictor of Alzheimer Disease, Vascular Dementia, and All Dementia among Community- Dwelling Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:881–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malmstrom TK, Voss VB, Cruz-Oliver DM, Cummings-Vaughn LA, Tumosa N, Grossberg GT, Morley JE. The Rapid Cognitive Screen (Rcs): A Point-of-Care Screening for Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:741–4. doi: 10.1007/s12603-015-0564-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, Anker SD, Bauer JM, Bernabei R, Cesari M, Chumlea WC, Doehner W, Evans J, Fried LP, Guralnik JM, Katz PR, Malmstrom TK, McCarter RJ, Gutierrez Robledo LM, Rockwood K, von Haehling S, Vandewoude MF, Walston J. Frailty Consensus: A Call to Action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:392–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phibbs CS, Holty JE, Goldstein MK, Garber AM, Wang Y, Feussner JR, Cohen HJ. The Effect of Geriatrics Evaluation and Management on Nursing Home Use and Health Care Costs: Results from a Randomized Trial. Med Care. 2006;44:91–5. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000188981.06522.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilgrim AL, Baylis D, Jameson KA, Cooper C, Sayer AA, Robinson SM, Roberts HC. Measuring Appetite with the Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire Identifies Hospitalised Older People at Risk of Worse Health Outcomes. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20:3–7. doi: 10.1007/s12603-015-0533-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao AV, Hsieh F, Feussner JR, Cohen HJ. Geriatric Evaluation and Management Units in the Care of the Frail Elderly Cancer Patient. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:798–803. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.6.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reijnierse EM, Trappenburg MC, Blauw GJ, Verlaan S, de van der Schueren MA, Meskers CG, Maier AB. Common Ground? The Concordance of Sarcopenia and Frailty Definitions. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:371 e7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR, Wieland GD, English PA, Sayre JA, Kane RL. Effectiveness of a Geriatric Evaluation Unit. A Randomized Clinical Trial. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1664–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198412273112604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubenstein LZ, Wieland D, English P, Josephson K, Sayre JA, Abrass IB. The Sepulveda Va Geriatric Evaluation Unit: Data on Four-Year Outcomes and Predictors of Improved Patient Outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1984;32:503–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1984.tb02235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solomon DH. Geriatric Assessment: Methods for Clinical Decision Making. JAMA. 1988;259:2450–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, Adams J, Rubenstein LZ. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: A Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. Lancet. 1993;342:1032–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92884-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson MM, Thomas DR, Rubenstein LZ, Chibnall JT, Anderson S, Baxi A, Diebold MR, Morley JE. Appetite Assessment: Simple Appetite Questionnaire Predicts Weight Loss in Community-Dwelling Adults and Nursing Home Residents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1074–81. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.5.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woo J, Leung J, Morley JE. Validating the Sarc-F: A Suitable Community Screening Tool for Sarcopenia? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:630–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]