Abstract

A complaint of dysphagia suggests difficulty in swallowing and is characterized based on the symptoms and location of pathology. Oropharyngeal dysphagia is typically due to difficulty initiating a swallow and is generally due to structural, anatomic or neuromuscular abnormalities. Esophageal dysphagia arises after the swallow and causes include intrinsic structural pathology, extrinsic compression, or disruption in normal motility. Etiologies, methods of evaluation, and management options of dysphagia are reviewed here.

Evaluation and management of the patient with dysphagia requires a structured assessment to identify functional, neurologic, inflammatory, and malignant causes.

Introduction

Dysphagia is defined as an abnormal delay in the movement of a food bolus from the oropharynx to the stomach.1 Patients often report difficulty swallowing.2 Dysphagia is a common symptom in the general population, however, dysphagia always represents a pathologic process. Swallowing encompasses three phases: oral (preparatory) phase, oropharyngeal (transfer) phase, and the esophageal phase. Often, dysphagia involves overlap of both the oropharyngeal and esophageal phases. Specific etiologies will be discussed here.

Epidemiology

Few population-based studies are available on the prevalence of dysphagia in the community.3 There are several structural, socioeconomic, age, and sex factors that affect the incidence of dysphagia.4, 5 Based on limited data, the prevalence of dysphagia in the general population is estimated around 20%, and it is estimated to affect up to 50% to 66% of people over 60 years of age.6 Dysphagia is more prevalent in women than men across all age groups.3 Older populations, patients with a history of stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis are more likely to report dysphagia.7 In younger populations, dysphagia is often associated with an underlying systemic illness, such as autoimmune diseases, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), or eosinophilic esophagitis. Despite this high prevalence, only half of patients with dysphagia will report their symptoms to clinicians.7 Dysphagia is an alarm symptom and is not a part of normal aging. Any new reports of dysphagia should prompt a systematic approach to aid in diagnosis and treatment.

History & Clinical Approach to Dysphagia

Patient-provided history often helps to differentiate oropharyngeal versus esophageal dysphagia. The normal swallow mechanism involves easy passage of a food bolus from the oropharynx to the esophagus. Symptoms of oropharyngeal dysphagia generally arise within seconds after swallowing, and patients often report drooling, coughing, nasal regurgitation, aspiration, or choking. Clinicians can use the following questions to help determine the origin of symptoms.

Does it take longer than one second to pass food from the mouth to the esophagus?

What type of food or liquids cause symptoms?

Are symptoms intermittent or progressive?

Is there heartburn?

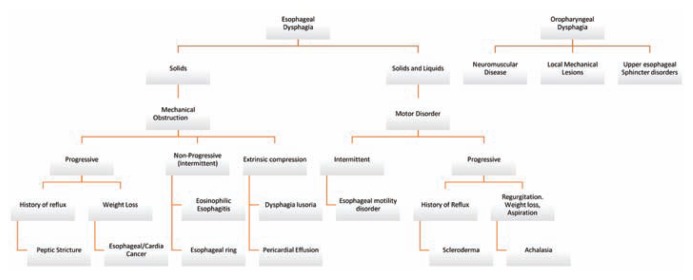

Patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia often recount experiences of delayed food bolus passage. Patients with esophageal dysphagia, on the other hand, will often recount the sensation of food “stuck in throat or chest” after swallowing. Patients may point to a specific region in the chest, however, this is often unreliable at pinpointing the actual location of the problem. Patients often localize pathology occurring in the distal esophagus as discomfort by their sternal notch. Dysphagia should be approached systematically as outlined in Figure 1. Given the complexity and multiple etiologies of dysphagia, it is important to differentiate the level of pathology early in the evaluation, as the differential diagnosis, work up, and management can be markedly different.

Figure 1.

Differential diagnosis of common presentations of dysphagia.

Oropharyngeal Dysphagia

The oropharyngeal phase of swallowing involves transferring a food bolus posteriorly to the epiglottis and then to the upper esophageal sphincter. The oropharynx comprises of the tongue, epiglottis, palatine tonsils, hard palate and soft palate. Anatomic abnormalities at any of these structures, such as upper esophageal sphincter (UES) dysfunction, can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia. Structural causes include head and neck malignancy, infections of the pharynx, vertebral osteophytes, prior head and neck radiation, proximal esophageal webs, thyromegaly, or Zenker’s diverticulum. Neuromuscular abnormalities are often the most common causes of oropharyngeal disorders. Cranial nerve injury, cortical, or supranuclear lesions after cerebral vascular accidents are common etiologies that lead to dysfunction in the oropharyngeal phase of swallowing.2

Patients presenting with symptoms of oral stasis of food, inability to form a food bolus in the mouth, coughing, or aspiration pneumonia should undergo further evaluation of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Furthermore, “silent aspiration,” which is, aspiration without cough or other outward signs of aspiration, can be the presentation of dysphagia in patients after a cerebral vascular accident.

Esophageal Dysphagia

Esophageal dysphagia can occur due to structural abnormalities or dysmotility. On initial presentation, esophageal dysphagia should be approached methodically with critical attention to patient-provided history. Mechanical or obstructive esophageal disorders are the most common causes of esophageal dysphagia, and patients generally present with dysphagia to solids alone with potential progression to include liquids.6 Mechanical obstruction can manifest with symptoms of intermittent dysphagia or progressive symptoms. In contrast, patient-reported symptoms of dysphagia with both solids and liquids most likely point to an underlying motility disorder.

Intermittent (Non-Progressive) Dysphagia

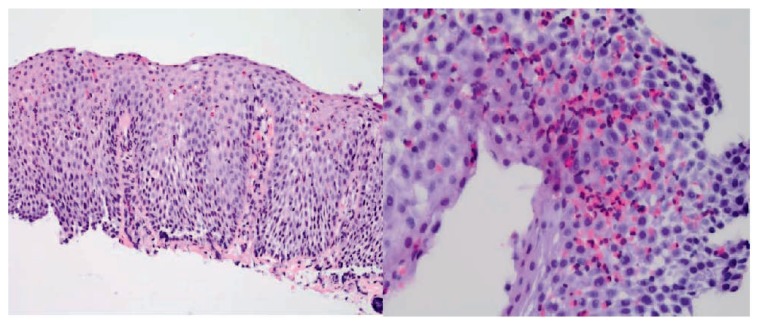

Patients will often present with a history of difficulty swallowing solids. In some clinical scenarios, symptoms may manifest with food bolus impaction. In younger patients with non-progressive dysphagia, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) should be considered. The exact etiology of EoE remains unknown, but it is thought to be related to esophageal reflux or atopy. EoE is diagnosed based on characteristic endoscopic findings and histologic evidence of mucosal eosinophilia.(Figure 2). However, several patients can present with a grossly normal-appearing esophagus, therefore, it is important to maintain a high level of suspicion regardless of endoscopic findings. Alternatively, esophageal webs and Schatzki rings can cause non-progressive dysphagia that can occur across all age groups. A Schatzki ring is a thin mucosal structure often found near the gastroesophageal junction.2 It manifests with symptoms of food bolus impaction, food regurgitation and often occurs after rushed meals.2

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph of an esophageal biopsy obtained during routine upper endoscopy shows squamous mucosa with increased intraepithelial eosinophils, basal hyperplasia, and elongation of papillae. Photo credit: Paul Friedman, MD, Department of Pathology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine.

Progressive Dysphagia

In contrast to intermittent or non-progressive dysphagia, progressive solid food dysphagia is worrisome for an esophageal stricture or carcinoma within the esophageal lumen. Peptic strictures are benign esophageal strictures that develop in patients with long-standing GERD and may present similarly to esophageal carcinoma. Weight loss is not common in patients with peptic strictures, as they often will modify their diet to more tolerable formulations.8 With long-standing peptic strictures and GERD, the risk of developing malignancy is increased. In patients with rapidly progressive dysphagia, weight loss, and anorexia, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma should be considered until proven otherwise. Esophageal adenocarcinoma is a growing health concern that is expected to increase in incidence over the next 10 years.9 Patients may or may not have a history of heartburn, and heartburn may have occurred in the past but not the present. Esophageal adenocarcinoma can occur anywhere in the esophageal lumen or at the gastric cardia. Gastric cardia lesions can also present with progressive dysphagia or give an achalasia like picture called pseudoachalasia.

Extrinsic Dysphagia

Based on location, the esophagus is subject to external compression by surrounding structures within the mediastinum.1 Diseases that lead to altered cardiac anatomy can progress to external compression of the esophagus. They may lead to hemodynamic compromise and luminal narrowing. Dysphagia lusoria is a term that refers to any congenital vascular abnormality leading to esophageal compression and the development of intermittent or persistent dysphagia symptoms. Anatomically, dysphagia lusoria typically refers to an aberrant right subclavian artery arising from the left side of the aortic arch, a double aortic arch, or a right aortic arch with left ligamentum arteriosum. Rarely, any clinical entity contributing to left atrial enlargement can lead to esophageal compression based on anatomic positioning.10 An enlarged thyroid, mediastinal masses or other mediastinal abnormalities may present similarly. Clinical clues suggestive of extrinsic compression from vascular or cardiac etiologies include respiratory distress, hypotension, and atypical chest pain.

Dysmotility

A report of dysphagia to liquids or a combination of solids and liquids should prompt concern for an abnormality in esophageal motility. The major motility disorders are broken down into achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm, hypertensive esophagus, and ineffective esophageal motility.11 Achalasia is the most commonly recognized disease within this category and is characterized by insufficient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and esophageal aperistalsis. This disease occurs as a result of degeneration of myenteric plexus ganglion cells, which leads to an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurons with resulting sustained lower esophageal sphincter contraction. The trigger for this overall process, however, often remains unclear with the exception of Chagas disease.12 Diffuse esophageal spasm is characterized by normal peristalsis with sporadic simultaneous contractions and generally presents as intermittent dysphagia with or without chest pain. Patients with a hypercontractile esophagus may also present with chest pain due to elevated esophageal and lower sphincter pressures. At the other end of the spectrum, motility tracings that demonstrate low amplitude pressures or failed peristalsis are considered ineffective esophageal motility.11, 13 Secondary causes of dysmotility include connective tissue disorders, parasitic infection, neurodegenerative diseases, pseudo-obstruction related to malignancy, or general aging.

Diagnostics

Recommended diagnostic approaches to evaluate dysphagia can vary and are generally guided by the patient’s reported symptoms and risk factors. The first line of diagnostic evaluation is centered around obtaining a detailed clinical history and physical exam (Figure 1). Investigative questions that characterize swallow initiation, postnasal regurgitation, deglutitive coughing, and resolution with repetitive swallowing have been shown to distinguish oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia with 80% accuracy.14 Specific features including chronicity, frequency, aggravating factors, and severity can help determine which additional diagnostic tools should be pursued. Evaluation of the oropharynx, neck and dentition may provide helpful clues. The main diagnostic tests to evaluate dysphagia include modified barium swallow, barium esophagram, endoscopy, and manometry.1

Barium esophagraphy is often utilized as the initial diagnostic test if there are clinical features that raise concern for complications related to blind endoscopic intubation. This can be applicable to patients at risk for laryngeal or esophageal malignancy, Zenker’s diverticulum, or a stricture related to radiation or caustic injury.15 The barium esophagram can also be helpful after an unrevealing endoscopy if there is clinical suspicion for morphologic abnormalities or dysmotility. If symptoms persist despite normal endoscopic and manometric evaluation, radiographic evaluation with ingestion of barium-coated foods or tablets can help identify subtle luminal narrowing or functional dysphagia.16 History that is suggestive of oropharyngeal dysphagia should prompt evaluation with a modified barium swallow, which can provide diagnostic information to help guide lifestyle modifications to alleviate symptoms and decrease aspiration risk.15

Endoscopy offers the dual benefits of providing both diagnostic information and a route of therapeutic intervention. It is especially valuable when symptoms are suggestive of an anatomic abnormality and if there is concern for a malignant or premalignant condition. This twofold application has also demonstrated a significant cost benefit when used as the initial diagnostic tool as barium swallow generally prompts follow-up testing or intervention.17 Evaluation of the utility of endoscopy in dysphagia workup demonstrated diagnostic value in 54% of cases with superior outcomes in males older than 40 years with associated heartburn, odynophagia, or weight loss.18

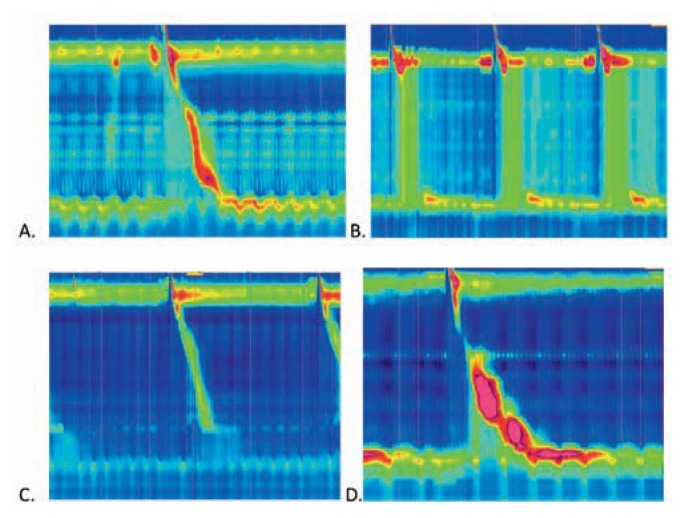

Manometry is employed if dysmotility is suspected, as it provides insight into esophageal peristalsis and sphincter function (Figure 3). Manometry helps differentiate between subsets of motility disorders and can help predict response to endoscopic and surgical interventions.19 The development of high-resolution manometry led to the creation of The Chicago Classification, an algorithmic format to diagnose motility-related pathology.13, 20

Figure 3.

High resolution manometry images demonstrate the pressures along the length of the esophagus (vertical axis) over time (horizonal axis) after swallows in the setting of common abnormalities. A. Normal esophageal manometry with normal progression of the pressure wave over time; B. Manometry in achalasia type II (classic achalasia) shows a lack of a normal peristaltic pressure wave; C. Manometry demonstrating weak lower esophageal sphincter (LES) tone that predisposes to GERD; D. Manometry demonstrating esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO) due to abnormally high pressures. Photo credit: Charlene Prather, MD, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine.

Therapeutics

Management of esophageal dysphagia is targeted to treat the underlying etiology. Mechanical obstruction due to intraluminal rings, webs, and benign strictures can be endoscopically dilated using a mechanical or balloon dilation. Bougie dilator is considered to be more effective and associated with less risks, as it provides both radial and axial forces and decreases the degree of force applied within the lumen. Balloon dilators, on the other hand, exert an isolated radial force, which allows for less dilation pressure but can be associated with higher perforation risk. Concurrent acid suppression therapy is frequently recommended with dilation to reduce stricture recurrence after successful dilation. Esophageal stents and intralesional steroids may be considered in refractory cases of benign strictures to help maintain lumen patency but are usually reserved for malignant strictures. Obstruction secondary to intraluminal masses, diverticula, and extrinsic compression may require surgical intervention.21

Dysphagia due to abnormal motility requires therapeutic approaches that target esophageal kinetics and pressure. Achalasia therapy focuses on reduction of the pressure created by the lower esophageal sphincter. The most effective nonsurgical intervention to date has been pneumatic dilation, which involves balloon dilation across the lower sphincter in an attempt to tear the muscle fibers in a controlled manner. A surgical myotomy may be performed laparoscopically and involves an anterior myotomy across the lower esophageal sphincter with success rates reported to range from 80 to 100%.11, 22 More recently, peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) has become an emerging technique for nonsurgical candidates, however, availability of this procedure currently remains limited to specialized centers.23 Botulinum injection and oral smooth muscle relaxants are less effective and are generally reserved for patients considered poor candidates for dilation or surgical intervention.11, 22 Distal esophageal spasm and hypercontractile esophagus management involves systemic therapy with oral smooth muscle relaxants and neuromodulatory agents.19

Functional dysphagia management can be challenging and involves elimination of motility-altering medications, a trial of high dose acid suppression, consideration for empiric bougie dilation, trials of neuromodulatory medications, and reassurance with simple lifestyle measures.6 The use of acid suppression stems from a variety of trials that have demonstrated an association of dysphagia with esophagitis severity, degree of gastric acidity, as well as reported improvement with empiric proton pump inhibitor therapy even in the absence of endoscopic pathology.24–26 Empiric bougie dilation and antidepressant use do not have significant data to support their use, but each can be considered after weighing the potential risks and benefits.6, 27 Conservative measures include eating in an upright position, avoiding exacerbating foods, thorough mastication, and alternating solid and liquid ingestion.24

Conclusion

An initial description of dysphagia offers an expansive list of potential etiologies, however, an organized approach to evaluation by means of thorough clinical history and use of modern diagnostic techniques can help determine underlying pathology and direct therapeutic options in a targeted manner.

Biography

Prianka Chilukuri, MD, (bottom left), and Florence-Damilola Odufalu, MD, (bottom right), are Fellows, and Christine Hachem, MD, (top) is an Associate Professor of Internal Medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Mo.

Contact: Christine.Hachem@health.slu.edu

Footnotes

Disclosure

None reported.

References

- 1.Abdel Jalil AA, Katzka DA, Castell DO. Approach to the patient with dysphagia. Am J Med. 2015;128:1138 e1117–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamada’s Handbook of Gastroenterology. 3 ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho SY, Choung RS, Saito YA, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR, 3rd, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for dysphagia: a USA community study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:212–219. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spieker MR. Evaluating dysphagia. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:3639–3648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eslick GD, Talley NJ. Dysphagia: epidemiology, risk factors and impact on quality of life--a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:971–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston BT. Oesophageal dysphagia: a stepwise approach to diagnosis and management. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:604–609. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkins T, Gillies RA, Thomas AM, Wagner PJ. The prevalence of dysphagia in primary care patients: a HamesNet Research Network study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20:144–150. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.02.060045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman MFL, Brandt LJ, editors. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. 10th ed. Vol. 1. Elsevier Saunders; 2016. pp. 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Napier KJ, Scheerer M, Misra S. Esophageal cancer: A Review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, staging workup and treatment modalities. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;6:112–120. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v6.i5.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vats HS. Dysphagia from extrinsic compression of esophagus by pericardial effusion. Clin Med Res. 2008;6:78–79. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2008.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter JE. Oesophageal motility disorders. Lancet. 2001;358:823–828. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05973-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1238–1249. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rohof WOA, Bredenoord AJ. Chicago Classification of Esophageal Motility Disorders: Lessons Learned. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19:37. doi: 10.1007/s11894-017-0576-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook IJ. Diagnostic evaluation of dysphagia. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:393–403. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Laufer I. Barium esophagography: a study for all seasons. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luedtke P, Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Weinstein DS, Laufer I. Radiologic diagnosis of benign esophageal strictures: a pattern approach. Radiographics. 2003;23:897–909. doi: 10.1148/rg.234025717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esfandyari T, Potter JW, Vaezi MF. Dysphagia: a cost analysis of the diagnostic approach. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2733–2737. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varadarajulu S, Eloubeidi MA, Patel RS, Mulcahy HE, Barkun A, Jowell P, et al. The yield and the predictors of esophageal pathology when upper endoscopy is used for the initial evaluation of dysphagia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:804–808. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zerbib F, Roman S. Current therapeutic options for esophageal motor disorders as defined by the chicago classification. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:451–460. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE, Schwizer W, Smout AJ, et al. Chicago classification criteria of esophageal motility disorders defined in high resolution esophageal pressure topography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(Suppl 1):57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Standards of Practice C. Egan JV, Baron TH, Adler DG, Davila R, Faigel DO, et al. Esophageal dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Current therapies for achalasia: comparison and efficacy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:21–35. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arora Z, Thota PN, Sanaka MR. Achalasia: current therapeutic options. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2017;8:101–108. doi: 10.1177/2040622317710010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aziz Q, Fass R, Gyawali CP, Miwa H, Pandolfino JE, Zerbib F. Functional esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1368–1379. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armstrong D, Talley NJ, Lauritsen K, Moum B, Lind T, Tunturi-Hihnala H, et al. The role of acid suppression in patients with endoscopy-negative reflux disease: the effect of treatment with esomeprazole or omeprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:413–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Triadafilopoulos G. Nonobstructive dysphagia in reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:614–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colon VJ, Young MA, Ramirez FC. The short- and long-term efficacy of empirical esophageal dilation in patients with nonobstructive dysphagia: a prospective, randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:910–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]