Abstract

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common clinical problem, affecting millions of people worldwide. Patients are recognized by both classic and atypical symptoms. Acid suppressive therapy provides symptomatic relief and prevents complications in many individuals with GERD. Advances in diagnostic and therapeutic modalities have improved our ability to identify and manage disease complications. Here, we discuss the pathophysiology and effects of GERD, and provide information on the clinical approach to this common disorder.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease affects millions of people worldwide with significant clinical implications.

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a very common digestive disorder worldwide with an estimated prevalence of 18.1–27.8% in North America.1 Approximately half of all adults will report reflux symptoms at some time.2 According to the Montreal definition, GERD is a condition of troublesome symptoms and complications that result from the reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus.3 Diagnosis of GERD is typically based on classic symptoms and response to acid suppression after an empiric trial. GERD is an important health concern as it is associated with decreased quality of life and significant morbidity.4 Successful treatment of GERD symptoms has been associated with significant improvement in quality of life, including decreased physical pain, increased vitality, physical and social function, and emotional well-being. While GERD medications are not particularly expensive, the cost of treating GERD patients has been deemed 2-fold more costly than comparable individuals without GERD.5 This cost difference is likely due to higher morbidity in GERD patients and the higher cost of managing complications of inappropriately treated GERD.

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Risk factors for GERD include older age, excessive body mass index (BMI), smoking, anxiety/depression, and less physical activity at work.6–8 Eating habits may also contribute to GERD, including the acidity of food, as well as size and timing of meals, particularly with respect to sleep. Recreational physical activity appears to be protective, except when performed post-prandially.6, 9

Gastroesophageal reflux is primarily a disorder of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) but there are several factors that may contribute to its development. The factors influencing GERD are both physiologic and pathologic. The most common cause is transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs). TLESRs are brief moments of lower esophageal sphincter tone inhibition that are independent of a swallow.10 While these are physiologic in nature, there is an increase in frequency in the postprandial phase and they contribute greatly to acid reflux in patients with GERD. Other factors include reduced lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure, hiatal hernias, impaired esophageal clearance, and delayed gastric emptying.8, 11

Symptoms

The classic and most common symptom of GERD is heartburn. Heartburn is a burning sensation in the chest, radiating toward the mouth, as a result of acid reflux into the esophagus. However, only a small percentage of reflux events are symptomatic. Heartburn is also often associated with a sour taste in the back of the mouth with or without regurgitation of the refluxate.

Notably, GERD is a common cause of non-cardiac chest pain.12, 13 It is important to distinguish between the underlying cause of the chest pain because of the potentially serious implications of cardiac chest pain and varied diagnostic and treatment algorithms based on etiology.13 A good clinical history may elicit GERD symptoms in patients with non-cardiac chest pain pointing to GERD as a potential etiology.

Although classic symptoms of GERD are easily recognized, extraesophageal manifestations of GERD are also common but not always recognized. Extraesophageal symptoms are more likely due to reflux into the larynx, resulting in throat clearing and hoarseness. It is not uncommon for patients with GERD to complain of a feeling of fullness or a lump in the back of their throat, referred to as globus sensation.14 The cause of globus is not well understood but it is thought that exposure of the hypopharynx to acid leads to increased tonicity of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES).14 Furthermore, acid reflux may trigger bronchospasm, which can exacerbate underlying asthma, thereby leading to cough, dyspnea, and wheezing.15 Some GERD patients may also experience chronic nausea and vomiting.

It is important to screen patients for alarm symptoms associated with GERD as these should prompt endoscopic evaluation. Alarm symptoms may suggest a possible underlying malignancy. Upper endoscopy is not required in the presence of typical GERD symptoms. However, endoscopy is recommended in the presence of alarm symptoms and for screening of patients at high risk for complications (i.e. Barrett’s esophagus, including those with chronic and/or frequent symptoms, age > 50 years, Caucasian race, and central obesity). Alarm symptoms include dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and odynophagia (painful swallowing), which may represent presence of complications such as strictures, ulceration, and/or malignancy. Other alarm signs and symptoms include, but are not limited to, anemia, bleeding, and weight loss.16

GERD symptoms should be considered as distinct from dyspepsia. Dyspepsia is defined as epigastric discomfort, without heartburn or acid regurgitation, lasting longer than one month. It can be associated with bloating/epigastric fullness, belching, nausea, and vomiting. Dyspepsia is an entity that may be managed differently from GERD and may prompt endoscopic evaluation, as well as testing for H. pylori.20

Complications

Left untreated, GERD can result in several serious complications, including esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus. Esophagitis can vary widely in severity with severe cases resulting in extensive erosions, ulcerations and narrowing of the esophagus.17 Esophagitis may also lead to gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Upper GI bleeding may present as anemia, hematemesis, coffee-ground emesis, melena, and when especially brisk, hematochezia. Chronic esophageal inflammation from ongoing acid exposure may also lead to scarring and the development of peptic strictures, usually presenting with the chief complaint of dysphagia.11

Patients with persistent acid reflux may be at risk for Barrett’s esophagus, defined as intestinal metaplasia of the esophagus. In Barrett’s esophagus, the normal squamous cell epithelium of the esophagus is replaced by columnar epithelium with goblet cells, as a response to acid exposure.18 Changes of Barrett’s esophagus may extend proximally from the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) and have the potential to progress to esophageal adenocarcinoma, making early detection very important in the prevention and management of malignant transformation.19

Diagnosis

GERD is usually diagnosed clinically with classic symptoms and response to acid suppression. Heartburn with or without regurgitation is typically sufficient to suspect GERD, particularly when these symptoms are worse postprandially or when recumbent.20 The initiation of treatment with histamine type 2 (H2) receptor blockers or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) with subsequent cessation of symptoms is considered diagnostic. In patients who respond to empiric treatment, in the absence of alarm features or symptoms, no further workup is required.21

In some patients, reflux symptoms will persist despite treatment with high-dose PPIs. Additional tests may be warranted to evaluate for other causes of their symptoms and to screen for possible complications of GERD. It is important to note that the severity of reflux symptoms does not necessarily correlate with the extent of mucosal damage.

The most utilized diagnostic test for the evaluation of GERD and its possible complications is the upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, or esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). The primary benefit of endoscopy is direct visualization of the esophageal mucosa. This assists in diagnosis of complications of GERD such as esophagitis, strictures and Barrett’s esophagus. One endoscopic grading system of GERD severity is the Los Angeles classification, graded from A to D, with D being the most severe (Figure 1).22

Figure 1.

Endoscopic view of Los Angeles grade D esophagitis (circumferential esophageal erosions, ulceration, and inflammation).

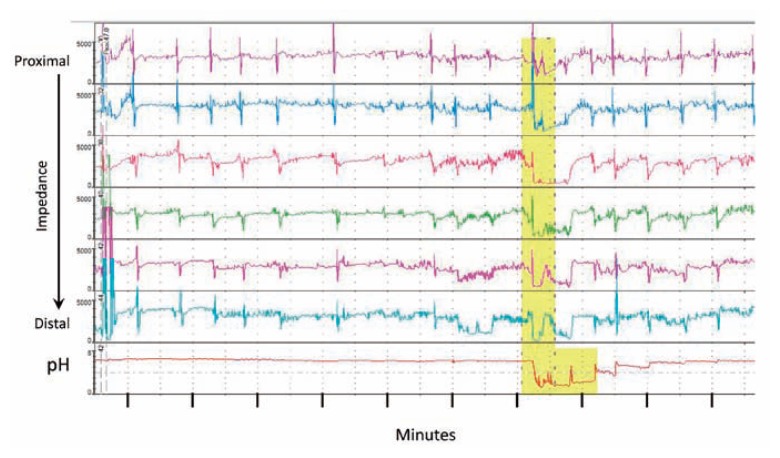

Ambulatory pH monitoring is considered the gold standard in the diagnosis of acid reflux. Ambulatory pH monitoring allows for the objective detection of acid reflux events and correlation with symptoms (Figure 2). This is particularly helpful in symptomatic patients with normal endoscopic findings. Ambulatory pH testing can be completed with good reproducibility (84–93%), sensitivity (96%), and specificity (96%).23 To complete the test, pH probes (catheter or wireless capsule) are placed into the esophagus for 24 to 48 hours. Percent of time with an esophageal pH of less than 4 is the primary parameter used in the diagnosis of GERD. It has the benefit of detecting dynamic changes in pH while upright and recumbent. Furthermore, pH probes record the number of reflux events, the proximal extent of reflux, as well as the duration of reflux events. Symptom correlation is also noted between reflux and symptoms. This test can be performed on or off PPI therapy.

Figure 2.

High resolution esophageal impedance and pH tracings. Impedance (measure of electrical conductance) within the lumen of the esophagus is measured simultaneously using multiple probes and the measurements are displayed with the proximal measures at the top progressing distally towards the stomach. The bottom tracing is the pH at the most distal measurement point. Highlighted in yellow are measurements that document liquid reflux from the stomach correlating with a drop in pH indicating reflux of gastric acid. this tracing is a small snapshot of 24 hours of data.

The diagnostic yield of ambulatory esophageal pH testing can be improved with the addition of impedance testing in patients with suspected GERD (Figure 3). This test involves the same procedure of placing probes into the esophagus but measures electrical properties of esophageal contents. For example, liquid reflux has low impedance and high conductance while gaseous reflux, seen in belching, has high impedance with low conductance. Some patients sense reflux symptoms during times of both normal and excessive esophageal acid exposure and combination monitoring allows for detection of nonacid reflux events that would otherwise go unnoticed with pH monitoring alone.24, 25

While it has some utility in evaluating patients with dysphagia, the barium esophagram is a poor screening test for GERD. It has a very poor sensitivity (26%) and specificity (50%) for mild esophagitis compared to endoscopy. Reflux of barium often does not correlate well with reflux of acid in symptomatic patients, and in up to 20% of cases is positive in normal individuals.16 Sensitivity can be improved by using maneuvers to illicit reflux such as coughing, valsalva, and rolling from supine to the right lateral position.26 Fluoroscopic barium testing has better yield in the detection of severe esophagitis, peptic strictures, and hiatal hernia. However, even for this indication, it still carries a relatively poor sensitivity and specificity for the detection of acid reflux in comparison to ambulatory pH testing. Therefore, due to its poor utility, it is not recommended for routine diagnosis of GERD.16

Treatment

GERD patients should be assessed for alarm features, as these should prompt urgent endoscopic evaluation. If no alarm symptoms are present, initial management of GERD should be geared toward lifestyle modification. However, it is important to note that the majority of studies on lifestyle and dietary changes in GERD have not been well powered. Nevertheless, lifestyle changes remain first-line in management of GERD with a primary goal of symptom reduction and improvement in quality of life.27, 28

The only proven lifestyle modification for the management of GERD is head of bed (HOB) elevation.29 Head of bed elevation has been shown to decrease esophageal acid exposure and esophageal clearance time with subsequent reduction in symptoms in patients with supine GERD. In addition, is it advised that factors contributing to the incidence of TLESRs should also be minimized or avoided. These include smoking, heavy alcohol consumption, large evening meals, nighttime snacks, and high dietary fat intake.27 Weight loss is strongly encouraged in overweight GERD patients, but there is no documented benefit in those with normal weight.30 Although obesity is a risk factor for GERD, most bariatric surgeries exacerbate reflux. Additionally, all patients with GERD should avoid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) because of their role in disrupting physiologic mucosal protection mechanisms.

Medication therapy for GERD is targeted at symptom reduction and minimizing mucosal damage from acid reflux. While acid suppression is successful in the treatment of GERD, there does not appear to be a clear relationship between GERD severity and high gastric acid levels with the exception being Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.31

Many patients with heartburn try over-the-counter antacids prior to seeking medical attention. The primary acid suppressive medications include H2 blockers and proton pump inhibitors. H2 blockers decrease gastric acid secretion by inhibiting histamine stimulation of the parietal cell. Proton pump inhibitors work to decrease the amount of acid secreted from parietal cells into the gastric lumen. H2 blockers have been shown to have some symptomatic benefit above placebo, but in individuals without contraindication, PPIs are the most effective therapy.32 There is no clear role for prokinetic agents, such as metoclopramide, in the treatment of GERD.16

Proton pump inhibitors are the most potent class of antacid medications. They are dosed once or twice daily and are most effective if taken 30 to 60 minutes prior to meals. Many patients will have relapse of symptoms after the cessation of PPI, therefore lifelong therapy is often required.16 Recently, there has been a rise in concern of PPIs contributing to the development of bone fractures, electrolyte deficiencies, infections (e.g., Clostridium difficile, pneumonia), and renal insufficiency.33, 34 Given the theoretical risk of side effect from PPI therapy, the lowest dose required for maintenance should be used and periodic trials of weaning should be attempted.33

In GERD patients refractory to twice daily PPI dosing, there is some evidence to show that adding a nighttime H2 blocker can be beneficial.16, 35 In refractory cases, other disorders should be considered, notably: eosinophilic esophagitis, pill esophagitis, delayed gastric emptying, duodenogastric/bile reflux, irritable bowel syndrome, psychological disorders, achalasia, and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.36

The use of anti-reflux surgery (fundoplication) has been controversial. Studies show only minimal long-term symptomatic improvements with surgery over PPI therapy, paired with an increased incidence of dysphagia and dyspepsia. Patients who respond best to surgery are those who also respond well to PPIs and therefore may be managed medically. Conversely, PPI-refractory patients are unlikely to have benefit from surgery.16 Approximately half of all patients who undergo surgery eventually require surgical revision. Given the near-negligible difference in efficacy between surgery and PPI and the risk for postoperative complications and mortality, surgery should only be reserved for select patients. Choosing the best candidates for anti-reflux surgery remains a clinical challenge.

Summary

GERD is a common clinical problem with significant morbidity and potentially decreased quality of life. Early recognition of symptoms is integral to preventing complications of GERD. Behavioral changes and advances in acid suppression remain integral to its treatment.

Biography

Danisa M. Clarrett, MD, MS, (left), is a Fellow and Christine Hachem, MD, (right), is an Associate Professor of Internal Medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Mo.

Contact: Christine.Hachem@health.slu.edu

Footnotes

Disclosure

None reported.

References

- 1.El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63:871–880. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Locke GR, 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–1920. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Revicki DA, Wood M, Maton PN, Sorensen S. The impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Am J Med. 1998;104:252–258. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloom BS, Jayadevappa R, Wahl P, Cacciamanni J. Time trends in cost of caring for people with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:S64–69. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(01)02587-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng Z, Nordenstedt H, Pedersen NL, Lagergren J, Ye W. Lifestyle factors and risk for symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux in monozygotic twins. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:87–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarosz M, Taraszewska A. Risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux disease: the role of diet. Prz Gastroenterol. 2014;9:297–301. doi: 10.5114/pg.2014.46166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferriolli E, Oliveira RB, Matsuda NM, Braga FJ, Dantas RO. Aging, esophageal motility, and gastroesophageal reflux. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1534–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emerenziani S, Zhang X, Blondeau K, Silny J, Tack J, Janssens J, et al. Gastric fullness, physical activity, and proximal extent of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1251–1256. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herregods TV, Bredenoord AJ, Smout AJ. Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: new understanding in a new era. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:1202–1213. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter JE. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in the older patient: presentation, treatment, and complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:368–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.t01-1-01791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Curvers WL, Timmer R, Smout AJ. Determinants of perception of heartburn and regurgitation. Gut. 2006;55:313–318. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.074690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gastal OL, Castell JA, Castell DO. Frequency and site of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with chest symptoms. Studies using proximal and distal pH monitoring. Chest. 1994;106:1793–1796. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.6.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tokashiki R, Funato N, Suzuki M. Globus sensation and increased upper esophageal sphincter pressure with distal esophageal acid perfusion. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:737–741. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-1134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irwin RS, French CL, Curley FJ, Zawacki JK, Bennett FM. Chronic cough due to gastroesophageal reflux. Clinical, diagnostic, and pathogenetic aspects. Chest. 1993;104:1511–1517. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.5.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308–328. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, et al. High prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and esophagitis with or without symptoms in the general adult Swedish population: a Kalixanda study report. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:275–285. doi: 10.1080/00365520510011579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaheen NJ, Richter JE. Barrett’s oesophagus. Lancet. 2009;373:850–861. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60487-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khademi H, Radmard AR, Malekzadeh F, Kamangar F, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Johansson M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of age and alarm symptoms for upper GI malignancy in patients with dyspepsia in a GI clinic: a 7-year cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dent J, Armstrong D, Delaney B, Moayyedi P, Talley NJ, Vakil N. Symptom evaluation in reflux disease: workshop background, processes, terminology, recommendations, and discussion outputs. Gut. 2004;53(Suppl 4):iv1–24. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang WH, Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Wong WM, Lam SK, Karlberg J, et al. Is proton pump inhibitor testing an effective approach to diagnose gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with noncardiac chest pain?: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1222–1228. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.11.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172–180. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiener GJ, Morgan TM, Copper JB, Wu WC, Castell DO, Sinclair JW, et al. Ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring. Reproducibility and variability of pH parameters. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:1127–1133. doi: 10.1007/BF01535789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pritchett JM, Aslam M, Slaughter JC, Ness RM, Garrett CG, Vaezi MF. Efficacy of esophageal impedance/pH monitoring in patients with refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease, on and off therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:743–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin KM, Ueda RK, Hinder RA, Stein HJ, DeMeester TR. Etiology and importance of alkaline esophageal reflux. Am J Surg. 1991;162:553–557. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(91)90107-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson JK, Koehler RE, Richter JE. Detection of gastroesophageal reflux: value of barium studies compared with 24-hr pH monitoring. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:621–626. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.3.8109509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meining A, Classen M. The role of diet and lifestyle measures in the pathogenesis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2692–2697. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeVault KR, Castell DO American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:190–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan BA, Sodhi JS, Zargar SA, Javid G, Yattoo GN, Shah A, et al. Effect of bed head elevation during sleep in symptomatic patients of nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1078–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraser-Moodie CA, Norton B, Gornall C, Magnago S, Weale AR, Holmes GK. Weight loss has an independent beneficial effect on symptoms of gastrooesophageal reflux in patients who are overweight. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:337–340. doi: 10.1080/003655299750026326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirschowitz BI. A critical analysis, with appropriate controls, of gastric acid and pepsin secretion in clinical esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90062-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richter JE, Campbell DR, Kahrilas PJ, Huang B, Fludas C. Lansoprazole compared with ranitidine for the treatment of nonerosive gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1803–1809. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laine L. Proton pump inhibitors and bone fractures? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(Suppl 2):S21–26. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dial MS. Proton pump inhibitor use and enteric infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(Suppl 2):S10–16. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xue S, Katz PO, Banerjee P, Tutuian R, Castell DO. Bedtime H2 blockers improve nocturnal gastric acid control in GERD patients on proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1351–1356. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fass R, Gasiorowska A. Refractory GERD what is it? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:252–257. doi: 10.1007/s11894-008-0052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]