Abstract

Digital tomosynthesis (DTS) is an emerging technology that provides cross-sectional, three-dimensional imaging similar to computed tomography (CT) at a fraction of the radiation dose and cost. In this article, we describe multiple cases where our pediatric orthopedic surgeons have used DTS imaging to help in clinical management of fracture healing.

Introduction

There has been a longstanding interest in reducing radiation dose through the American College of Radiology (ACR) Image Gently campaign in an effort to reduce the number of radiation induced cancers, while still maintaining diagnostic quality exams for clinicians to appropriately manage their patients. 1–3 In pediatric radiology, the main contribution of radiation dose comes from computed tomography (CT) scans.4 CT has proven incredibly useful and will likely remain the workhorse for cross-sectional imaging for complex problems in the foreseeable future.5 However, as technologies advance, there has been an interest in reducing the number of CT scans overall, while still maintaining diagnostic accuracy and one of the efforts has been in tomosynthesis.

Tomosynthesis is decades-old technology that is regaining prominence due to recent technical innovations.6, 7 The new iteration named digital tomosynthesis (DTS) is able to provide cross-sectional, three-dimensional imaging like CT at a fraction of the radiation dose and cost. This technology fills an imaging sweet spot between radiographs and CT. DTS is a radiographic technique that produces cross-sectional images with similar in-plane resolution to radiography.8 DTS utilizes a standard x-ray tube, a flat-panel detector overlaid with an anti-scatter grid, and a motorized tube crane to move the x-ray tube. A reconstruction algorithm allows for production of multiple cross-sectional images at a much lower dose than that of CT. In the chest, DTS dose is approximately 5% of CT and about twice the dose of a two-view chest computed radiography (CR). The typical DTS dose ranges from 0.27 mGy to 0.31mGy depending on the patient’s age and size.8, 9

DTS is gaining acceptance in adult imaging and has been studied mostly for breast and lung cancer screening applications where patients undergo repeated rounds of imaging.10–13 DTS has also been studied in the setting of fracture healing and orthopedic hardware.14–18 In pediatric populations, DTS has only been used to screen and stage cystic fibrosis.19 However, this technology has not been widely studied in pediatric imaging and we believe that this technology holds great promise in this arena.

Regulatory Overview

Several DTS systems are FDA-approved for general diagnostic imaging (chest, bone and abdomen) under the 510(k) pathway.20–22 Approval under the 510(k) pathway means that the FDA has determined that a new medical device is equivalent (defined as the device achieves the same results as a predicate device and the FDA agrees it is safe) to an already FDA approved medical device. FDA approval means that physicians can use the device for the approved indications.

The ACR has also come out with guidance on how to bill chest, upper extremity, lower extremity and spine DTS exams. They recommend using CPT code 76100, Radiologic examination, single plane body section (e.g. tomography), other than with urography.23

Children’s Mercy Hospital Implementation

Children’s Mercy currently has GE DTS equipment in four of our imaging locations; and our radiologists, radiologic technologists and orthopedic surgery department under went training on how to obtain and post-process the images.

Pediatric Case Studies

Case 1

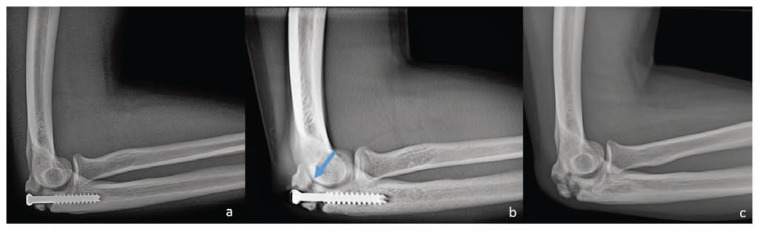

A 15-year-old male with history of right olecranon stress fracture treated with screw fixation and local bone graft presented for follow up. His course was complicated by a postoperative infection and subsequent surgical debridement of the infection ten days after initial surgery. He was on appropriate antibiotics and was doing well without significant pain around the fracture site. The orthopedic surgeon wanted to know if there was enough healing around the hardware that it could be removed.

The initial radiograph (Figure 1a) was interpreted as “… No increased callus is appreciated on the lateral projection at the fracture site when compared with the most recent x-ray.”

Figure 1.

15-year-old male with history of right olecranon stress fracture was treated with screw fixation. His course was complicated by a post-operative infection. (a) Lateral radiograph of the elbow demonstrates a screw across an olecranon fracture. (b) A selected slice from a digital tomosynthesis exam demonstrates a bony bridge between the proximal fracture fragments (arrow). (c) Lateral radiograph of the elbow two months after the initial radiographs demonstrates healing bony bridging of the olecranon fracture after screw removal.

DTS imaging of the elbow was performed the same day to get a more detailed evaluation of healing. The DTS images (Figure 1b) showed bridging of the bone around the screw. The orthopedist then felt comfortable enough with the demonstrated degree of healing to remove the infected screw two weeks after these exams. At a follow up visit three months later, the patient was doing well and participating in weight training without any new complaints and an additional radiograph showed moderate bony callus bridging the previous fracture site (Figure 1c).

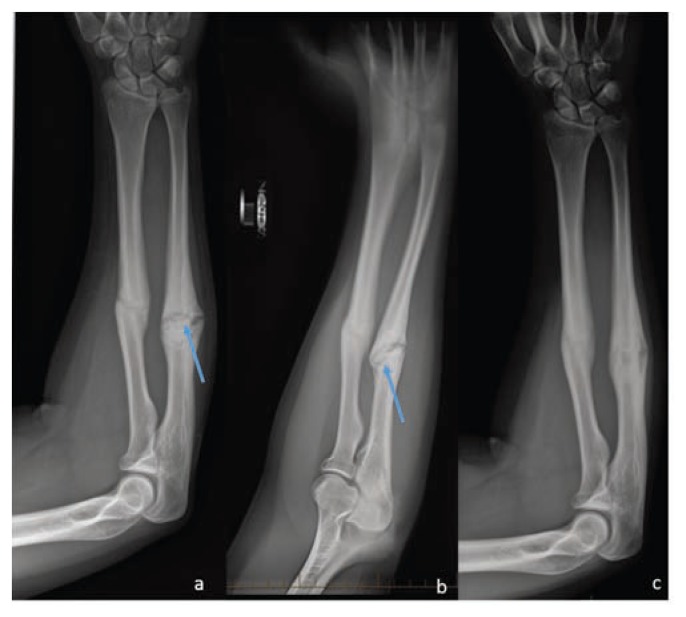

Case 2

A 15-year-old male presented for a six-month follow-up evaluation of left forearm fractures.

The initial radiograph (Figure 2a) was interpreted as “…radial fracture appears to be healing well with signs of remodeling and minimal remaining lucency. The ulnar fracture continues to have a significant amount of periosteal reaction, some signs of remodeling, but there is also a fair amount of residual lucency noted causing suspicion for delayed union versus nonunion.”

Figure 2.

15-year-old male who presents for a 6-month follow-up of his left forearm fractures. (a) Frontal radiograph of the forearm demonstrates a healing radial diaphysis fracture (white arrow) and a persistent lucent fracture line spanning the width of an ulnar diaphysis fracture (blue arrow). (b) A selected slice from a digital tomosynthesis exam demonstrates a bony bridge between the two fragments of the ulnar fracture (blue arrow). (c) A follow up frontal radiograph of the forearm demonstrates both the radial and ulnar fractures are healing with bony bridging across both fractures with no persistent fracture lines.

Because of the concern for fracture non-union, the orthopedist then ordered DTS imaging of the forearm the same day. The DTS images (Figure 2b) demonstrated healing across the fracture, prompting a decision to start a bone stimulator and re-examine in one month with radiographs. The radiographs performed a month later (Figure 2c) showed a less distinct fracture line consistent with a healing fracture with no concern for non-union.

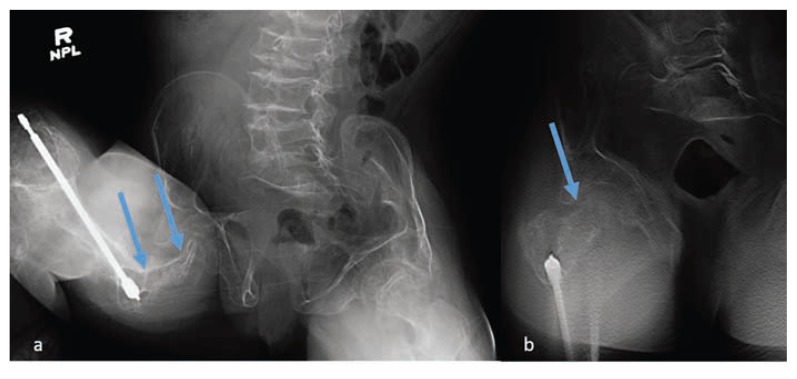

Case 3

A 13-year-old female with a past medical history of osteogenesis imperfecta presented to the emergency department with pain in the right hip after a wheelchair injury. The patient was in her wheelchair in the back of the school bus and the driver slammed on the brakes causing her chest to hit her knees. Radiographs on this patient were difficult to interpret due to her bony demineralization.

The initial radiograph (Figure 3a) was interpreted as “Probable fracture of the right femoral neck with shortening and collapse on the frontal view. This could be further evaluated with CT if clinically indicated.” The orthopedic team was consulted and recommended a DTS to further evaluate (Figure 3b). The DTS was interpreted as “Tomographic images demonstrate diffuse osteopenia and chronic deformity related to osteogenesis imperfecta. Though there is contour irregularity of the femoral neck, it appears chronic in nature. No cortical offset or acute fracture line is seen.” The patient was then discharged from the emergency department and followed up in orthopedic clinic in one month. At the one month follow up, repeat radiographs of the right femur did not show any evidence of new bone formation or healing fracture.

Figure 3.

13-year-old female with a history of osteogenesis imperfecta presents with right hip pain after a wheelchair injury. (a) Frontal radiograph of the pelvis is suspicious for femoral neck fracture because of contour deformity in the femoral neck (arrows). there is also diff use bony demineralization making interpretation more challenging. (b) A selected slice from a digital tomosynthesis exam demonstrates that the femoral neck cortex in question is intact (arrow).

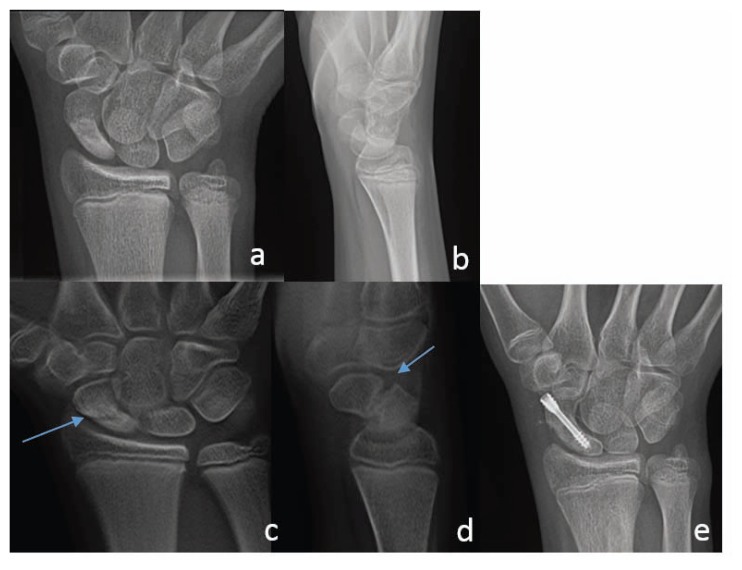

Case 4

A 13-year-old male with history of ejection during a rollover motor vehicle collision while riding in the trunk of a car presented three months later with right wrist pain.

Wrist radiographs were obtained which showed a non-displaced scaphoid mid-waist fracture. The images were interpreted as “Findings suggestive of healing scaphoid fracture.” The orthopedist placed the patient into a thumb spica cast for the next four weeks with plans to follow up for further evaluation of this fracture with hand specialist.

At the visit with the hand specialist, radiographs (Figure 4a, b) were obtained which were interpreted as “… there is similar alignment of scaphoid fracture fragments with progressive healing. The proximal half of the scaphoid demonstrates increasing sclerosis. The previously noted subchondral cystic changes have resolved.” The orthopedist was suspicious for fracture non-union and wanted a more detailed evaluation with DTS. The DTS (Figure 4c, d) showed “fracture through the scaphoid waist. There is palmar angulation of the distal fracture fragment with distraction of approximately 3 mm at the superior medial aspect of the fracture. The fracture margins are sclerotic. No osseous bridging is identified. There is subtle sclerosis of the proximal pole which may suggest avascular necrosis.”

Figure 4.

13-year-old male presents with right wrist pain three months after a rollover motor vehicle accident. Frontal (a) and lateral (b) radiographs of the right wrist demonstrates a nondisplaced scaphoid waist fracture with some sclerosis around the fracture line. No discrete fracture line lucency is imaged. selected slices from a frontal (c) and lateral (d) digital tomosynthesis exam of the wrist demonstrate a 3 mm gap between the two fragments of the scaphoid fracture indicating non-union. (e) A follow up frontal radiograph of the wrist demonstrates a screw across the scaphoid fracture with no avascular necrosis or remaining lucent fracture line.

After the DTS results, the orthopedist decided that the fracture requires surgical fixation, likely with bone graft from the distal radius with possible insertion of a compression screw. After surgery, the patient did well and was discharged from clinic after radiographs showed good healing (Figure 4e).

Discussion

The above examples are just a few of the cases where our radiologists and clinicians feel DTS has added value to our care of children. In these four cases, DTS proved useful in answering a specific clinical question about fractures after radiographs were inconclusive.

DTS has a large advantage over radiographs because DTS is a cross-sectional imaging modality that can diminish the blur ring in radiographs contributed by overlying structures. DTS also has some advantages over CT, the most obvious being lower ionizing radiation dose and lower cost. Another advantage is that DTS is integrated with radiographic equipment and this equipment is of ten physically located much closer to the orthopedic clinic area than CT, and is often much more available. Additionally, two of our patients had metallic orthopedic hardware located close to the region in question that would have caused beam-hardening artifact if a CT was performed in that region, limiting evaluation of the adjacent structures.

In this small case series, we have shown that DTS can excel in answering specific pediatric orthopedic questions. More study is needed to fully investigate whether DTS has a bigger role in pediatric orthopedic imaging and to define the clinical questions for which DTS excels. The cases that we have presented could form a basis for further systematic evaluation of this new imaging modality.

Biography

Sherwin Chan, MD, is Assistant Professor Pediatric Radiology, Children’s Mercy, University of Missouri, Kansas City, Kansas City, Mo.

Contact: sschan@cmh.edu

Footnotes

Disclosure

Children’s Mercy Hospital has received a research grant from GE Healthcare to work on optimizing GE imaging protocols for pediatric imaging that was active from 2015 to 2016. The authors had full control of the data and the information submitted for publication. None of the authors are employees of or consultants for the sponsor.

References

- 1.Applegate KE, Cost NG. Image Gently: a campaign to reduce children’s and adolescents’ risk for cancer during adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2013 May;52(5 Suppl):S93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MD. ALARA, image gently and CT-induced cancer. Pediatr Radiol. 2015 Apr;45(4):465–470. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-3198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miglioretti DL, Johnson E, Williams A, et al. The use of computed tomography in pediatrics and the associated radiation exposure and estimated cancer risk. JAMA Pediatr. 2013 Aug 1;167(8):700–707. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathews JD, Forsythe AV, Brady Z, et al. Cancer risk in 680,000 people exposed to computed tomography scans in childhood or adolescence: data linkage study of 11 million Australians. Bmj. 2013 May 21;346:f2360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frush DP, Goske MJ. Image Gently: toward optimizing the practice of pediatric CT through resources and dialogue. Pediatr Radiol. 2015 Apr;45(4):471–475. doi: 10.1007/s00247-015-3283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobbins JT. Tomosynthesis imaging: at a translational crossroads. Med Phys. 2009 Jun;36(6):1956–1967. doi: 10.1118/1.3120285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobbins JT, Godfrey DJ. Digital x-ray tomosynthesis: current state of the art and clinical potential. Phys Med Biol. 2003 Oct;48(19):R65–106. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/48/19/r01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dobbins JT, McAdams HP. Chest tomosynthesis: technical principles and clinical update. Eur J Radiol. 2009 Nov;72(2):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vult von Steyern K, Bjorkman-Burtscher IM, Weber L, Hoglund P, Geijer M. Effective dose from chest tomosynthesis in children. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2014;158(3):290–298. doi: 10.1093/rpd/nct224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedewald SM, Rafferty EA, Rose SL, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography. Jama. 2014 Jun 25;311(24):2499–2507. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee CI, Cevik M, Alagoz O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of combined digital mammography and tomosynthesis screening for women with dense breasts. Radiology. 2015 Mar;274(3):772–780. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14141237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou SH, Kicska GA, Pipavath SN, Reddy GP. Digital tomosynthesis of the chest: current and emerging applications. Radiographics. 2014 Mar-Apr;34(2):359–372. doi: 10.1148/rg.342135057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobbins JT, 3rd, McAdams HP, Sabol JM, et al. Multi-Institutional Evaluation of Digital Tomosynthesis, Dual-Energy Radiography, and Conventional Chest Radiography for the Detection and Management of Pulmonary Nodules. Radiology. 2017 Jan;282(1):236–250. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016150497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Mokhtar N, Shah J, Marson B, Evans S, Nye K. Initial clinical experience of the use of digital tomosynthesis in the assessment of suspected fracture neck of femur in the elderly. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015 Jul;25(5):941–947. doi: 10.1007/s00590-015-1632-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geijer M, Borjesson AM, Gothlin JH. Clinical utility of tomosynthesis in suspected scaphoid fracture. A pilot study. Skeletal Radiol. 2011 Jul;40(7):863–867. doi: 10.1007/s00256-010-1049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gothlin JH, Geijer M. The utility of digital linear tomosynthesis imaging of total hip joint arthroplasty with suspicion of loosening: a prospective study in 40 patients. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:594631. doi: 10.1155/2013/594631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ha AS, Lee AY, Hippe DS, Chou SH, Chew FS. Digital Tomosynthesis to Evaluate Fracture Healing: Prospective Comparison With Radiography and CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015 Jul;205(1):136–141. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machida H, Yuhara T, Sabol JM, Tamura M, Shimada Y, Ueno E. Postoperative follow-up of olecranon fracture by digital tomosynthesis radiography. Jpn J Radiol. 2011 Oct;29(8):583–586. doi: 10.1007/s11604-011-0589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vult von Steyern K, Bjorkman-Burtscher IM, Hoglund P, Bozovic G, Wiklund M, Geijer M. Description and validation of a scoring system for tomosynthesis in pulmonary cystic fibrosis. Eur Radiol. 2012 Dec;22(12):2718–2728. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2534-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anonymous. 510(k) Premarket Notification Submission for Discovery XR656 with \/olumeRAD. FDA; 2013. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/k132261.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anonymous. 510(k) Premarket Notification Submission for X-ray TV System SonialVision G4. FDA; 2015. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf14/k142341.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anonymous. 510(k) Premarket Notification Submission for FUJIFILM Tomosynthesis option for FDR AcSelerate Stationary X-ray System. FDA; 2012. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf12/k121499.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.ACR. ACR-Radiology-Coding-Source-Nov-Dec-2016-Q-and-A. [Accessed January 30, 2018]. Available at: https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/Coding-Source/ACR-Radiology-Coding-Source-Nov-Dec-2016-Q-and-A.