Abstract

Background

This study was to estimate the incidence rate of cleft lip and/or cleft palate (CL/P) in Taiwan from 1994 to 2013, and to assess the time trend over these years.

Methods

Retrospective data analysis was performed on records of all newborns with CL/P treated at Chang Gung Craniofacial Center, the only treatment center for CL/P in Taiwan, from 1994 to 2013. Three-year moving average rates were computed and linear regression was used to explore the annual average percentage change.

Results

From 1994 to 2013, 7282 newborns with CL/P were identified, corresponding to an annual rate of 1.48‰ (95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.45‰–1.52‰). There was a significant decline of rate of cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL ± P) (−2.9% ± 0.2%, p < 0.0001) but slightly increase of rate of cleft palate (CP) only (+0.2% ± 0.07%, p = 0.004).

Conclusion

From 1994 to 2013, the annual rate of incidence of CL/P was 1.48‰ in Taiwan. The 2.9% annual decline of the rate was mainly from the CL ± P group, not the CP group.

Keywords: Cleft lip, Cleft palate, Incidence, Prenatal diagnosis

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

The incidence of orofacial clefts varied mainly from genetic and environmental reasons. Due to improving sonographic technology, prenatal diagnosis of cleft lip and/or cleft palate becomes accurate, and hence, the incidence is subject to alter.

What this study adds to the field

A decline in the incidence of orofacial clefts was observed from the group of cleft lip with or without cleft palate rather than the group of cleft palate in Taiwan between 1994 and 2013.

Cleft lip and/or cleft palate (CL/P) are the most common congenital craniofacial anomalies with an incidence of 1:700–1:1000. Multiple factors contribute to the development of cleft defect, including genetics, environments, and socioeconomics [1], [2]. The prevalence is higher among Asians and people of native North American descent, followed by Caucasians, and least among Africans. The reported rate was 1.33/1000 live births for Asians, 1.30 for Chinese, 1.34 for Japanese, and 1.47 for other Asians [3]. In Taiwan, the annual incidence was reportedly 1.29/1000 in 1972 [4] and 1.12/1000 from 1980 to 1992 [5]. During 2002 and 2009, the overall annual prevalence of cleft deformities among 1,705,192 births was 1‰ for cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL ± P) and 0.4‰ for cleft palate (CP) [6]. Environmental factors such as radiation, smoking, anticonvulsants, and alcohol consumption during pregnancy had been proposed as contributing factors to cleft development while folic acid was reported as a protective factor [7], [8], [9]. Low socioeconomic status, on the other hand, was found to be an indirect factor contributing to birth defect [10].

Prenatal diagnosis by sonography has become increasingly prevalent with improved accuracy [11]. The first sonography detection of cleft lip was reported in 1981 [12]. Major craniofacial anomalies can be identified by sonogram as early as 12 weeks of gestation [13]. The accuracy of transabdominal two-dimensional sonographic screening for orofacial clefts in a low-risk population ranged from 9% to 50% [14]. Three-dimensional sonography demonstrated enhanced accuracy of 100% for all clefts involving the primary palate and 86% of clefts involving secondary palate [14], [15]. One study showed the rate of prenatal diagnosis of CL ± P increased from 11% to 50% from 1999 to 2008 [16]. While termination can only be performed for fetuses associated with severe anomalies, European studies reported that termination rate for solitary cleft lip and palate ranged from 3.3% to 9% [17].

In Taiwan, prenatal transabdominal ultrasound screening became readily accessible at a low cost since the establishment of National Health Insurance in 1995. Abortion is legally permitted before 24 weeks of pregnancy if the fetus has severe congenital anomalies or causes detrimental effect to the mother. Due to insufficient data on the birth prevalence and epidemiological characteristics of a facial cleft in Taiwan, we consider whether the prenatal diagnosis has an impact on the incidence of the facial cleft in Taiwan. In a culture where orofacial clefts are not well accepted and where there is not a stigma on abortion as compared to certain Catholic traditions, we suspect that the advent of orofacial cleft prenatal screening may influence the rate of abortion and the subsequent incidence of cleft deformity.

In this study, we investigated the change in the incidence of orofacial clefts in Taiwan from 1994 to 2013 during the enforcement of National Health Insurance since1995.

Methods

An institutional review board approval was obtained from the authors' institution. Data on all new births with cleft lip and palate in Taiwan from January 1994 to December 2013 were collected from two main centers in the hospitals: The Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CGMH) in Linkou and the CGMH in Kaohsiung. The Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Department in both hospitals held the only Craniofacial Center where all patients with cleft deformity were referred. Data on the prenatal diagnosis rate of cleft lip and palate were partially available from chart review of all patients undergoing treatment at CGMH in Linkou under one physician between January 2009 and December 2012. As CP was rarely diagnosed prenatally, data on the frequency of prenatal diagnoses were concentrated on CL ± P.

Live birth data was obtained from the Department of Statistics at the Ministry of Interior in Taiwan. The incidence of oral clefts in the present study was based on live births. Rates were calculated as the numbers of event in 1994–2013 dividing by the live births of the same year. To minimize fluctuation of the annual rates, 3-year moving average rates were computed [18]. The 95% CIs of the rate were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution. Linear regression of the rate has been used to look at annual average percentage change [19]. Interaction between time and group (CL ± P vs. CP) in the linear regression was added to examine whether there is difference in the slopes between two groups. P < 0.05 was taken to be statistically significant.

Results

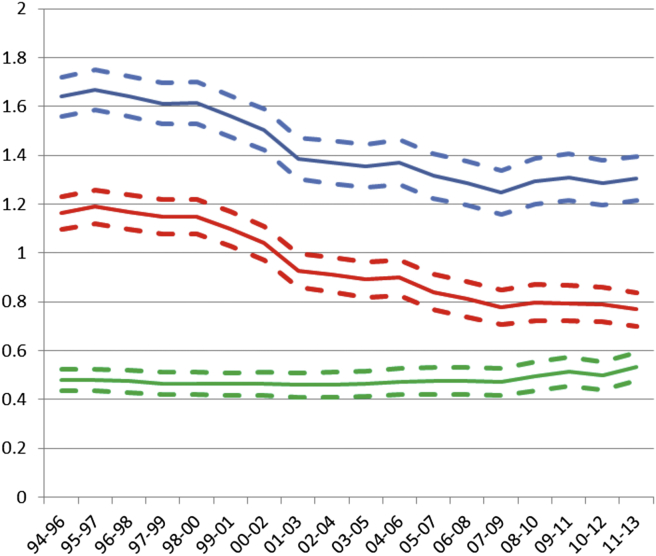

A total of 7282 new patients with CL/P from 1994 to 2013 were identified. The estimate of the birth incidence was based on 4,912,739 total live births, according to the Department of Statistics at the Ministry of Interior in Taiwan. The annual incidence for cleft births over the 20-year period was 1.48/1000 (95% CI = 1.45–1.52), or 1/675 live births [Table 1]. Linear regression revealed on the 3-year moving average rates that there was a significant decline of CL ± P rate (−2.9% ± 0.2%, p < 0.0001) but slightly increase of CP rate (+0.2% ± 0.07%, p = 0.0040) [Fig. 1].

Table 1.

Births with cleft lip and/or cleft palate in Taiwan between 1994 and 2013.

| Year | Total live births | Case numbers |

Incidence (per 1000 live births) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total clefts | CL ± P | CP | Total clefts | CL ± P | CP | ||

| 1994 | 322,938 | 493 | 340 | 153 | 1.53 | 1.053 | 0.473 |

| 1995 | 329,581 | 573 | 414 | 159 | 1.74 | 1.256 | 0.482 |

| 1996 | 325,545 | 539 | 383 | 156 | 1.66 | 1.176 | 0.480 |

| 1997 | 326,002 | 525 | 370 | 155 | 1.61 | 1.135 | 0.479 |

| 1998 | 271,450 | 451 | 324 | 127 | 1.66 | 1.194 | 0.468 |

| 1999 | 283,661 | 445 | 317 | 128 | 1.57 | 1.118 | 0.471 |

| 2000 | 305,312 | 493 | 348 | 145 | 1.61 | 1.139 | 0.475 |

| 2001 | 260,354 | 387 | 267 | 120 | 1.49 | 1.026 | 0.462 |

| 2002 | 247,530 | 343 | 230 | 113 | 1.39 | 0.929 | 0.457 |

| 2003 | 227,070 | 289 | 185 | 104 | 1.27 | 0.815 | 0.458 |

| 2004 | 216,419 | 317 | 215 | 102 | 1.46 | 0.993 | 0.471 |

| 2005 | 205,854 | 278 | 181 | 97 | 1.35 | 0.879 | 0.471 |

| 2006 | 204,459 | 269 | 170 | 99 | 1.32 | 0.831 | 0.484 |

| 2007 | 204,414 | 263 | 166 | 97 | 1.29 | 0.812 | 0.475 |

| 2008 | 198,733 | 248 | 155 | 93 | 1.25 | 0.780 | 0.468 |

| 2009 | 191,310 | 228 | 139 | 89 | 1.19 | 0.727 | 0.465 |

| 2010 | 166,886 | 242 | 149 | 93 | 1.45 | 0.893 | 0.557 |

| 2011 | 196,627 | 257 | 153 | 104 | 1.31 | 0.778 | 0.529 |

| 2012 | 229,481 | 348 | 205 | 143 | 1.52 | 0.893 | 0.623 |

| 2013 | 199,113 | 294 | 162 | 132 | 1.48 | 0.814 | 0.663 |

| Total | 4,912,739 | 7282 | 4873 | 2409 | 1.48 | 0.992 | 0.490 |

Abbreviations: CL ± P: Cleft lip with or without cleft palate; CP: Cleft palate only.

Fig. 1.

The 3-year moving averages of orofacial cleft rate per 1000 live births in Taiwan, 1994–2013. Blue line was for the total, red line for cleft lip with or without cleft palate, and green line for cleft palate only. Broken lines were the upper limit and lower limit of the rates.

The prenatal diagnostic rate of CL ± P from January 2009 to December 2012 was found to be 73% among all children with varied severity of cleft deformity undergoing treatment by the senior author. A total of 148 children were seen, among which 108 confirmed the diagnosis from the prenatal ultrasound.

Discussion

The incidence of the facial cleft was found to be 1.48/1000 live births from 1994 to 2013 in Taiwan. Linear regression showed that there was decreased trend of CL ± P rate (−2.9% ± 0.2%, p < 0.0001) but slightly increase of CP rate (+0.2% ± 0.07%, p = 0.0040). Prenatal detection of cleft lip is high, and although a mild incomplete type of cleft lip may be missed in diagnosis, the detection rate is expected to rise with the improvement of imaging technology and increasing public awareness. The incidence of facial cleft varied in geographical distribution because of ethnic and environmental differences, and the results of the present study agreed with the reported incidence among Asians at an average of 1.56/1000 live births [3]. In East Asia, the incidence of facial cleft was 1.44–1.46/1000 live births in Japan [20], [21], 1.81/1000 live births in Korea [22], and 1.94/1000 live births in the Philippines [23]. In Chinese population, the incidence of facial cleft varied from 1.2 to 3.27/1000 live births [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. Emanuel et al. [4] previously found an incidence of 1.29/1000 among 25,814 total live births in Taipei, Taiwan. One recent study showed the overall incidence of cleft deformity was 0.1% from 2002 to 2009, with a trend toward decreasing incidence over time [6]. This is further supported by the present study, where the incidence of CL ± P decreased significantly from 1994 to 2013.

Multiple factors have been proposed as contributing factors for the change in the incidence of craniofacial cleft deformity in Taiwan, over the last two decades. These include improved infant survival, accumulating environmental teratogens, change in maternal nationalities, folate supplementation, and sonographic, prenatal diagnosis. Several studies have suggested an increasing effect of the genetic and environmental factors in craniofacial clefts such as methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase gene [9], [29]. Concerning the rising variability of maternal nationalities in Taiwan, a study found no significant difference in the prevalence of craniofacial clefts among newborns of Taiwan-born mothers and foreign-born mothers, such as females of South-East Asian descent [30], although we have seen lots of foreign-born mothers in our craniofacial center. Others have proposed a protective effect of folate supplementation in decreasing the development of craniofacial clefts [7], [8].

The development and popularity of prenatal sonographic diagnosis of cleft deformity might have greatly contributed to the change in incidence although the reason for a routine prenatal scanning is not to increase the termination of pregnancy but to provide information and the best care for both fetus and mother. Some previous studies showed no significant change in the prevalence of orofacial clefts despite improved prenatal detection [31] and rare cases of termination secondary to isolated CL ± P in Western countries [13], [31], [32], [33]. However, in the Netherlands, transabdominal ultrasound screening is available at 20 weeks of gestation since 2007, and its registry reported a slowly declining trend in the incidence of CL ± P and a stable incidence of CP [34]. The responses of pregnant women to the prenatal diagnosis of orofacial cleft also differ with culture and religion, influencing the decision to terminate a pregnancy [35].

The decision to terminate a pregnancy secondary to fetal deformity is certainly complicated. A study showed that 0–27% of prenatal diagnoses of nonsyndromic clefts lead to termination [36]. One study conducted in Argentina where abortion is legally restricted, most parents supported the continuation of pregnancy after prenatal diagnosis, but 6.4% of 165 parents chose to terminate pregnancy [37]. On the other hand, in Israel, 23 out of 24 cases with cleft lip diagnosed prenatally were terminated after respective parents consulted with other parents with affected children who have received plastic, reconstructive surgery [38]. Thus, in Taiwan, the combination of prenatal diagnosis and unprohibited elective abortion prior to 24 weeks of gestation may contribute to the significant decrease in the incidence of CL ± P. Our study showed that while the incidence of cleft lip and palate decreased over time, the incidence of CP only remained clinically unchanged and slightly increased [Fig. 1]. This is in agreement with prior studies [34], [39] and potentially related to the fact CP only is frequently not diagnosed prenatally.

The limitation of the present study included an incomplete capture of all newborn with craniofacial clefts in Taiwan. Our study was based on patients who received treatment in the craniofacial center, excluding other cases receiving treatment in other hospitals, and, therefore, may be an underestimate. The number missing is expected to be minimal and not significantly influence the data in this study, as Chang Gung Craniofacial Centers in Linkou and Kaohsiung are the only center for treatment of cleft in Taiwan. Comparing the Chang Gung Database with the National Birth Registration Database, case numbers were not completely the same on CL ± P and CP [6]. This could be attributed to later diagnosis of CP that may or may not be obvious at birth, or incorrectly defining the cleft type at the government registration. We would not have captured cases that were left untreated or referred internationally, but Taiwan's geographic isolation and cleft treatment expertise made this occasion less likely. Finally, the actual number of such termination of pregnancy, as well as precise relationship among prenatal diagnosis, termination of pregnancy, and the decrease of incidence in Taiwan remain a topic of future investigation.

Conclusion

The annual rate of incidence of CL/P was 1.48% in Taiwan between 1994 and 2013, but 2.9% annual decline of the rate was mainly from the CL ± P group rather than the CP group. This phenomenon might result from combination of improving prenatal diagnosis and unprohibited termination, as well as no prenatal diagnosis, for CP only. The results from this study provide important information for healthcare providers in Taiwan and worldwide countries.

Source of support

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgment

We wish to thank Dr. Jui-Ping Lai, Dr. Wan-Ching Chang, and Miss. Shiao-Hua Lee for the help in providing patient's data. The source of information is from Chang Gung Craniofacial Center and Department of Statistics at the Ministry of Interior in Taiwan.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Derijcke A., Eerens A., Carels C. The incidence of oral clefts: a review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;34:488–494. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(96)90242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melnick M. Cleft lip and palate: a system of management. 1990. Cleft lip and palate: etiology and pathogenesis; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper M.E., Ratay J.S., Marazita M.L. Asian oral-facial cleft birth prevalence. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2006;43:580–589. doi: 10.1597/05-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emanuel I., Huang S.W., Gutman L.T., Yu F.C., Lin C.C. The incidence of congenital malformations in a Chinese population: the Taipei collaborative study. Teratology. 1972;5:159–169. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420050206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw C.K., Chen C.J., Lee M.L. An epidemiological study of lip and palate cleft in Taiwan: prevalence trend and familial clustering. Tzu Chi Med J. 1995;7:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lei R.L., Chen H.S., Huang B.Y., Chen Y.C., Chen P.K., Lee H.Y. Population-based study of birth prevalence and factors associated with cleft lip and/or palate in Taiwan 2002–2009. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bienengräber V., Malek F.A., Möritz K.U., Fanghänel J., Gundlach K.K., Weingärtner J. Is it possible to prevent cleft palate by prenatal administration of folic acid? An experimental study. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2001;38:393–398. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_2001_038_0393_iiptpc_2.0.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilcox A.J., Lie R.T., Solvoll K., Taylor J., McConnaughey D.R., Abyholm F. Folic acid supplements and risk of facial clefts: national population based case-control study. BMJ. 2007;334:464. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39079.618287.0B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao W.L., Wu M., Shi B. Folic acid rivals methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene-silencing effect on MEPM cell proliferation and apoptosis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;292:145–154. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang J., Carmichael S.L., Canfield M., Song J., Shaw G.M., National Birth Defects Prevention Study Socioeconomic status in relation to selected birth defects in a large multicentered US case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:145–154. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthews M.S., Cohen M., Viglione M., Brown A.S. Prenatal counseling for cleft lip and palate. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:1–5. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199801000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christ J.E., Meininger M.G. Ultrasound diagnosis of cleft lip and cleft palate before birth. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;68:854–859. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198112000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergé S.J., Plath H., Van de Vondel P.T., Appel T., Niederhagen B., Von Lindern J.J. Fetal cleft lip and palate: sonographic diagnosis, chromosomal abnormalities, associated anomalies and postnatal outcome in 70 fetuses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;18:422–431. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7692.2001.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maarse W., Bergé S.J., Pistorius L., van Barneveld T., Kon M., Breugem C. Diagnostic accuracy of transabdominal ultrasound in detecting prenatal cleft lip and palate: a systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35:495–502. doi: 10.1002/uog.7472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Ten P., Adiego B., Illescas T., Bermejo C., Wong A.E., Sepulveda W. First-trimester diagnosis of cleft lip and palate using three-dimensional ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40:40–46. doi: 10.1002/uog.10139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paterson P., Sher H., Wylie F., Wallace S., Crawford A., Sood V. Cleft lip/palate: incidence of prenatal diagnosis in Glasgow, Scotland, and comparison with other centers in the United Kingdom. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2011;48:608–613. doi: 10.1597/09-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Offerdal K., Jebens N., Syvertsen T., Blaas H.G., Johansen O.J., Eik-Nes S.H. Prenatal ultrasound detection of facial clefts: a prospective study of 49,314 deliveries in a non-selected population in Norway. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;31:639–646. doi: 10.1002/uog.5280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong Y., Hedayat A.S., Sinha B.K. Surveillance strategies for detecting changepoint in incidence rate based on exponentially weighted moving average methods. J Am Stat Assoc. 2008;103:843–853. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hothorn T., Bretz F., Westfall P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J. 2008;50:346–363. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Natsume N., Kawai T., Kohama G., Teshima T., Kochi S., Ohashi Y. Incidence of cleft lip or palate in 303738 Japanese babies born between 1994 and 1995. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;38:605–607. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2000.0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Natsume N., Suzuki T., Kawai T. The prevalence of cleft lip and plate in Japanese. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;26:232–236. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(88)90168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim S., Kim W.J., Oh C., Kim J.C. Cleft lip and palate incidence among the live births in the Republic of Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:49–52. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray J.C., Daack-Hirsch S., Buetow K.H., Munger R., Espina L., Paglinawan N. Clinical and epidemiologic studies of cleft lip and palate in the Philippines. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1997;34:7–10. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1997_034_0007_caesoc_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu D.N., Li J.H., Chen H.Y., Chang H.S., Wu B.X., Lu Z.K. Genetics of cleft lip and cleft palate in China. Am J Hum Genet. 1982;34:999–1002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper M.E., Stone R.A., Liu Y., Hu D.N., Melnick M., Marazita M.L. Descriptive epidemiology of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in Shanghai, China, from 1980 to 1989. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2000;37:274–280. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_2000_037_0274_deoncl_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J., Han Y., Lin M.C. Cleft lip and/or palate in a low-resource province in China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;93:146–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Z., Ren A., Liu J., Zhang L., Ye R., Li S. High prevalence of orofacial clefts in Shanxi Province in northern China, 2003–2004. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:2637–2643. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan K.L. Incidence and epidemiology of cleft lip/palate in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap. 1988;17:311–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fogh-Andersen P. Genetic and non-genetic factors in the etiology of facial clefts. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967;1:22–29. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen Y.M., Wu H.W., Deng F.L., See L.C. Ethnic variations in the estimated prevalence of orofacial clefts in Taiwan, 2004 to 2006. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2011;48:337–341. doi: 10.1597/08-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell K.A., Allen V.M., MacDonald M.E., Smith K., Dodds L. A population-based evaluation of antenatal diagnosis of orofacial clefts. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2008;45:148–153. doi: 10.1597/06-202.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maarse W., Pistorius L.R., Van Eeten W.K., Breugem C.C., Kon M., Van den Boogaard M.J. Prenatal ultrasound screening for orofacial clefts. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38:434–439. doi: 10.1002/uog.8895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ensing S., Kleinrouweler C.E., Maas S.M., Bilardo C.M., Van der Horst C.M., Pajkrt E. Influence of the 20-week anomaly scan on prenatal diagnosis and management of fetal facial clefts. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44:154–159. doi: 10.1002/uog.13291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mink van der Molen A.B., Maarse W., Pistorius L., de Veye H.S., Breugem C.C. Prenatal screening for orofacial clefts in the Netherlands: a preliminary report on the impact of a national screening system. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2011;48:183–189. doi: 10.1597/09-021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadagad P., Pinto P., Powar R. Attitudes of pregnant women and mothers of children with orofacial clefts toward prenatal diagnosis of nonsyndromic orofacial clefts in a semiurban set-up in India. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011;44:489–493. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.90833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson N., Sandy J.R. Prenatal diagnosis of cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2003;40:186–189. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_2003_040_0186_pdocla_2.0.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wyszynski D.F., Perandones C., Bennun R.D. Attitudes toward prenatal diagnosis, termination of pregnancy, and reproduction by parents of children with nonsyndromic oral clefts in Argentina. Prenat Diagn. 2003;23:722–727. doi: 10.1002/pd.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blumenfeld Z., Blumenfeld I., Bronshtein M. The early prenatal diagnosis of cleft lip and the decision-making process. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1999;36:105–107. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1999_036_0105_tepdcl_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patil S.B., Kale S.M., Khare N., Math M., Jaiswal S., Jain A. Changing patterns in demography of cleft lip-cleft palate deformities in a developing country: the smile train effect – what lies ahead? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:327–332. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f95b9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]