Abstract

BACKGROUND.

Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is decreased in individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD). Pre-clinical and clinical reports suggest that the glutamate release inhibitor riluzole increases BDNF and may have antidepressant properties. Here we report serum (sBDNF) and plasma (pBDNF) levels from a randomized controlled, adjunctive, sequential parallel comparison design trial of riluzole in MDD.

METHODS.

Serum and plasma BDNF samples were drawn at baseline and weeks 6 and 8 from 55 subjects randomized to adjunctive treatment with riluzole or placebo for 8 weeks.

RESULTS.

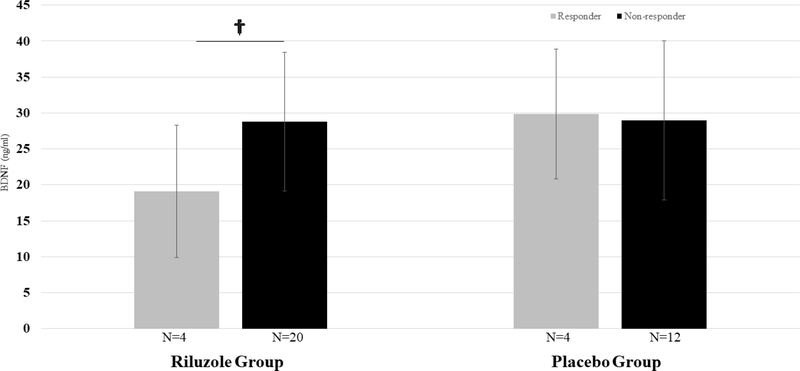

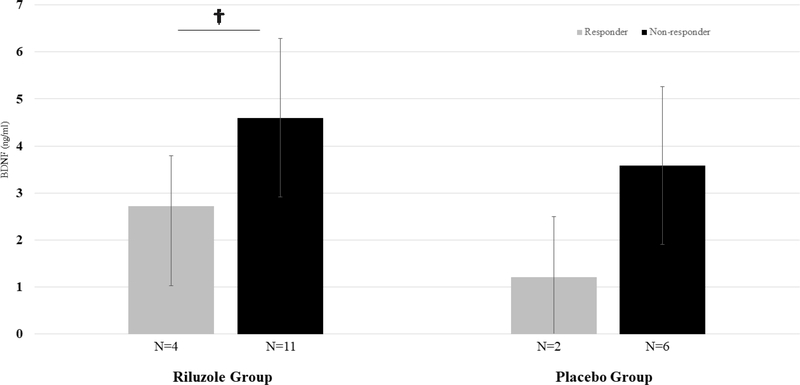

Riluzole responders had lower baseline serum (19.08ng/ml [SD 9.22] v. 28.80ng/ml [9.63], p=0.08) and plasma (2.72ng/ml [1.07] v. 4.60ng/ml [1.69], p=0.06) BDNF compared to non-responders at a trend level. This pattern was nominally seen in placebo responders for baseline pBDNF to some degree (1.21ng/ml [SD 1.29] v. 3.58ng/ml [SD 1.67], p=0.12) but not in baseline sBDNF.

LIMITATIONS:

A number of limitations warrant comment, including the small sample size of viable BDNF samples and the small number of riluzole responders.

CONCLUSIONS.

Preliminary evidence reported here suggests that lower baseline BDNF may be associated with better clinical response to riluzole.

Keywords: Riluzole, BDNF, MDD

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a substantial public health problem, affecting over 300 million people globally each year [1]. Unfortunately, its pathogenesis remains poorly understood. The monoaminergic hypothesis, which has dominated the field of mood disorders research for many decades, does not fully explain the underlying neurobiology of MDD, as demonstrated by the modest and delayed effects of monoaminergic-based antidepressants. Emerging evidence supports the basis of a neurotropic hypothesis, which posits that mood disorders may result from neuronal atrophy induced by chronic stress [2–4]. In animals, models of chronic stress result in a variety of pathologic effects in brain regions implicated in MDD, most notably the hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and nucleus accumbens [5–7]. In the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), chronic stress is associated with decreased dendritic branching and spine density. Similar changes are noted in the hippocampus with respect to overall size and new neuron number [5]. In contrast, chronic stress is associated with dendritic hypertrophy in the nucleus accumbens and amygdala [7–9]. It is hypothesized that reversal of a deficit or excess of trophic support in specific brain regions may ameliorate depressive symptoms [2, 7].

Additional support for the neurotrophic hypothesis comes from studies of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which has been shown to play a critical role in dendritic formation (Dijkhuizen & Ghosh, 2005), synaptogenesis [10], and neurogenesis [5, 11]. BDNF may also play an important role in the relationship among stress, neuronal atrophy, and depressive symptoms. A strong line of research supports this, including evidence that chronic stress reduces hippocampal BDNF, reduced levels of hippocampal BDNF found in post-mortem analyses of brains from depressed patients [12], and infusion of BDNF in rodents resulting in increased hippocampal synaptic transmission and neuronal proliferation [13, 14]. Furthermore, serum BDNF levels have been shown to be consistently reduced in patients with depression compared to healthy controls and often increase following treatment with antidepressants [15, 16].

Additionally, depressive response has been linked to BDNF Val66Met polymorphism, whereby Val66Met heterozygous patients have a higher response rate than Val66Met homozygous patients [17]. Rodent models demonstrating decreased prefrontal synaptogenesis in Met/Met mice following antidepressant administration suggest that the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism may attenuate antidepressant response in part by blocking synaptogenesis [18].

Riluzole, an agent approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, has been shown to have neuroprotective properties and may help ameliorate deficits in trophic support through what are believed to be direct effects on the glutamatergic system resulting in decreased glutamate release [19–21] and increased glutamate uptake [22]. Riluzole has been shown to stimulate neurotrophic growth factor expression, increase cell proliferation and enhance synaptic AMPA receptor activation [23–25], all potential neuroprotective and antidepressant mechanisms. Preclinical studies, open-label trials, and at least one placebo-controlled trial [26] in humans have suggested that riluzole may have antidepressant effects [27], although a recent double-blind placebo-controlled study conducted by our group was negative [28].

Previous studies have shown that riluzole enhances the expression and release of BDNF [29], suggesting it may serve as a marker of therapeutic response [30–32]. Most studies investigating the relationship between MDD and BDNF have evaluated serum BDNF (sBDNF). Plasma BDNF (pBDNF) has more recently been investigated, and is also shown to be lower in MDD compared with healthy controls [12]. BDNF is stored in platelets and released over time [33]. Hence assays measuring plasma BDNF, which include platelets, may be less time-sensitive and easier to carry out in practical clinical settings. Here we report on serum (sBDNF) and plasma (pBDNF) levels of BDNF from a subset of subjects in a multi-site double-blind, randomized controlled trial of riluzole as an augmentation strategy in treatment-resistant MDD. We hypothesized that riluzole treatment would increase low baseline sBDNF and pBDNF levels and that these changes would correspond with improvements in depressive symptoms.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the IRB at all involved institutions (Yale School of Medicine, Baylor School of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital [MGH]) and was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01204918). All subjects signed informed consent.

Participants

Adult outpatients ages 18–65 with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD), confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV were recruited for participation. Subjects were treatment-resistant, based on their non-response to 1–4 adequate antidepressant trials using the MGH Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire. Participants were either already on a therapeutic dose of a standard antidepressant (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, serotoninnorepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or bupropion) or were prospectively treated with one prior to randomization.

Study Design and Assessments:

Using a sequential, parallel comparison design [34], subjects (n=104) were randomized (2:3:3) to 8 weeks of riluzole, 8 weeks of placebo, or 4 weeks of placebo followed by 4 weeks of riluzole. Oral riluzole (50 mg twice daily) was adjunctive to a standard antidepressant that subjects were already taking. The primary study outcome was change in Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) at 8 weeks. The full details of the trial methodology were published previously [35].

BDNF Samples

BDNF was analyzed using human free BDNF Immunoassay (Quantikine Elisa, R and D systems, Cat# DBD00) with a standard range of 62.5–400pg/ml, sensitivity of 20pg/ml, and sample dilution of 1/20. Samples of sBDNF and pBDNF levels were drawn at baseline, 6 and 8 weeks in a subset of the total sample. While most samples were drawn in the morning, there was variability in the time of sample collection. sBDNF samples were collected by drawing whole blood samples, allowing for a 40-min incubation period at room temperature, then centrifuging at 2000g for 10 min at 4°C. sBDNF values were normalized for total protein. For pBDNF samples, whole blood was collected and immediately centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 rpm. Plasma supernatant was then immediately transferred to new tubes and stored at −80º C until processed. BDNF concentrations (serum and plasma) were determined via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Samples from one site were not analyzable due to an error in the processing method.

Statistical Analysis

Given that only a portion of subjects randomized contributed viable sBDNF or pBDNF samples, those who did and did not contribute BDNF samples were compared on demographic and clinical characteristics using two-sample, independent t tests (for continuous variables) or chisquare tests (for categorical variables). Linear regression was used to examine correlations among serum and plasma BDNF samples and change in depression severity. A general linear mixed model was used to examine BDNF trends over time. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 15.0 (College Station, TX).

Results

Demographics

Overall, 104 subjects were randomized, with the mean age being 46.1 years (SD 12.2), and 50 (48%) were males (Table 1). The mean (SD) number of adequate antidepressant treatment failures was 1.59 (0.80), with 42.3% of the sample having failed 2 or more adequate trials. The primary study outcome, which showed no evidence of riluzole having antidepressant effects over placebo in the total sample, has been reported previously [35]. Viable serum BDNF samples were collected and processed in 43 subjects with at least one time point and in 27 subjects at all 3 times points; viable plasma samples were collected in 27 subjects with at least one time point and in 17 subjects at all 3 time points. The mean (SD) age of the subjects with serum BDNF samples was 44.8 (10.6). The mean (SD) age of the subjects with plasma BDNF samples was 44.1 (10.9). Among the subjects who contributed a viable sBDNF sample, 51% were male; among the subjects who contributed viable pBDNF samples, 59% were male (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | Total Clinical Sample | Serum BDNF Sample | Plasma BDNF Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=104) | (N=43) | (N=27) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 46.1 (12.2) | 44.8 (10.6) | 44.1 (10.9) |

| Female, N (%) | 54 (51.9) | 21 | 11 |

| Race/Ethnicity, N (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 82 (78.8) | 32 | 24 |

| African American | 11 (10.6) | 4 | 2 |

| Hispanic | 13 (12.5) | 8 | 6 |

| Other | 7 (6.7) | 3 | 0 |

| Education completed, N (%) | |||

| Grade 6–12, or high school graduate | 17 (16.3) | 5 (11.6) | 3 |

| Some college | 34 (32.7) | 8 (18.6) | 8 |

| 4-year college graduate | 31 (29.8) | 19 (44.2) | 11 |

| Graduate/professional degree | 20 (19.2) | 10 (23.3) | 4 |

| Current marital status, N (%) | |||

| Single, never married | 38 (36.5) | 12(27.9) | 8 |

| Married, civil union, cohabitating | 29 (27.9) | 18 | 14 |

| Separated, divorced, widowed | 23 (22.1) | 9 | 2 |

| Total treatment failures, mean (SD) | 1.59 (0.80) | 1.6 (0.87) | 1.7 (0.99) |

| Baseline MADRS, mean (SD) | 29.5 (6.0) | 30.3 (5.7) | 29.1 (5.7) |

Those who contributed viable BDNF samples were not different from those who did not in terms of age, gender, race, ethnicity, total number of failed trials, employment status, current smoking status, baseline depression severity or percent improvement in depression severity during the trial. Those who contributed BDNF samples had more years of education (t=−2.44, p=0.016) and were more likely to be married (chi-square=6.45, p=0.040) compared to those who did not contribute BDNF samples.

Correlation between plasma and serum BDNF

Plasma and serum BDNF samples were not correlated at any time point with each other.

Baseline BDNF and depression severity

There was no statistically significant correlation between baseline pBDNF levels and baseline depression severity (coefficient=−.07, t=−1.01, p=0.32, n=23, r2=0.04), or sBDNF levels and baseline depression severity as measured by the MADRS (coefficient=.003, t=.01, p=0.99, n=49, r2=0.00).

Baseline BDNF and clinical outcomes

Baseline BDNF (serum and plasma) was not significantly correlated with improvement in depression due to riluzole (serum: r2=0.06, p=0.23, t=−1.22, n=24; plasma: r2=0.10, p=0.25, t=1.20, n=15). The same was true of improvement in depression due to placebo (serum: r2=0.01, p=0.58, t=0.56, n=30; plasma: r2=0.02, p=0.60, t=−0.53, n=17). Riluzole responders had a trend towards lower plasma and serum BDNF levels at baseline compared to non-responders (plasma: 2.72 [SD 1.07] v. 4.60 [SD 1.69], t=2.06, p=0.06, n=15; serum: 19.08 [SD 9.22] v. 28.80 [SD 9.63], t=1.85, p=0.08, n=24; FIGURES 1, 2). This trend was not seen in serum BDNF patterns of placebo responders compared to non-responders (responders 29.81 [SD 9.02] v. non-responder 28.96 [SD 11.06], t=−0.14, p=0.89, n=16) but was seen to some extent in plasma BDNF patterns of placebo responders (responders 1.21 [SD 1.29] v. non-responders 3.58 [SD 1.67], t=1.79, p=0.12, n=8). Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) tended to be large for comparisons of plasma and serum BDNF patterns in those who responded to riluzole (plasma: d=1.20, 95% CI −0.05–2.41; serum: d=1.02, 95% CI −0.11–2.12).

Figure 1.

Baseline serum BDNF, responders v. non-responders, by treatment assignment. †p<0.10; *p<0.05

Figure 2.

Baseline plasma BDNF, responders v. non-responders, by treatment assignment.†p<0.10; *p<0.05

BDNF trends over time

There were no consistent or statistically significant changes in serum or plasma BDNF over time in response to riluzole.

Discussion

The primary outcome of the parent clinical trial, change in depression severity over time, was negative, as reported previously [35]. The current report investigates the relationships among plasma and serum BDNF levels, and clinical response to riluzole in MDD. We found that responders due to riluzole had lower pre-treatment pBDNF and sBDNF compared to nonresponders at a trend level. There was no significant correlation between baseline BDNF levels and improvement in depressive symptoms. There was no correlation between plasma and serum BDNF at any time point and there were no consistent or significant changes over time to serum or plasma BDNF levels in response to riluzole. The lack of viable BDNF samples and extremely small sample sizes per cell likely resulted in unstable means, potentially obscuring correlations that may have emerged in a larger sample.

Though extremely preliminary, our findings suggest that individuals with MDD and low BDNF levels may be more responsive to riluzole treatment, though we cannot exclude the possibility that this is a non-specific effect. Given the very small sample sizes, these results should be interpreted with caution. Notably, the hypothesis that individuals with MDD and lower BDNF levels are more responsive to riluzole treatment is biologically plausible and tentatively supported by our findings. A tentative relationship between BDNF and potential antidepressant effects of riluzole is supported by pre-clinical studies linking increased BDNF expression to improved behavioral performance in paradigms sensitive to classical antidepressant treatment and measuring helplessness and anhedonia-like deficits [36, 37]. If low BDNF levels represent a potential biological sub-type of depression, then riluzole, which has been shown increase BDNF in vitro in murine astrocytes [24] and rodent hippocampal cells [23], may serve to restore BDNF to normal levels and hence reduce depressive symptoms and behaviors. Heterogeneity in baseline BDNF levels, accounted for by natural variation (age, gender, etc), may obscure signals that would emerge from more biologically stratified samples. Larger prospective studies would be necessary to determine whether such heterogeneity has contributed to conflicting reports regarding the antidepressant properties of riluzole [35, 38]

Mature BDNF and its precursor, pro-BDNF have divergent functions. Distinguishing mature BDNF, which binds to the tropomycin receptor kinase B and promotes cellular and synaptic plasticity, from pro BDNF, which binds to the p75 receptor and initiates cell death, may help clarify the role that BDNF plays in the etiology of MDD and depressive response. Because sBDNF levels, especially pro-sBDNF [15] levels, are especially low, new techniques may be needed to distinguish pro and mature BDNF. Though peripheral BDNF is correlated with cerebral cortex integrity [39] and is much easier to measure in humans than neural BDNF, the role of peripheral BDNF remains poorly understood. Most peripheral BDNF is stored in platelets and released through activation or clotting, the mechanisms of which remains incompletely understood [40]. Thus, minor differences in blood drawing, processing, or storage may be responsible for heterogeneity in sBDNF findings [41].

Measuring pBDNF in addition to sBDNF may help control for methodological differences that affect serum clotting. Reductions in both sBDNF and pBDNF have been identified in MDD [40]. Though riluzole responders in this study had both lower pre-treatment pBDNF and sBDNF compared to non-responders at a trend level, there was no correlation between pBDNF and sBDNF levels at any time point. Notably, a previous very large study and meta-analysis also found no correlation between plasma and serum BDNF [15]. This finding suggests that pBDNF and sBDNF measures may be independent, which raises additional questions about the role of peripheral BDNF in the etiology of MDD and differences in the methodological approaches to collect serum or plasma BDNF [40, 41].

Limitations

There are a number of limitations of this report which include the small sample size of viable BDNF samples, the small number of riluzole responders, the variability of time of venipuncture, and the post-hoc nature of the analysis. An additional limitation of the current study as well as most previous BDNF studies is failure to account for different forms of BDNF (mature v. pro-BDNF) that are present in the serum and have divergent functions. The enzyme that is part of the immunosorbent assay commonly used in previous BDNF studies binds to a site that is present on both pro-BDNF as well as mature BDNF.

Conclusions

The preliminary finding that subjects with lower baseline plasma or serum BDNF levels had a higher response rate to riluzole in this trial at trend level significance is of interest and warrants further exploration. However, larger studies are needed to confirm this. Given the heterogeneous nature of MDD, genetic testing exploring possible interactions among polymorphisms (i.e., BDNF Val66Met [21], baseline BDNF levels and clinical response may be able to elucidate mechanisms that underlie this purported finding. Despite these limitations and the need for replication to validate our results, the primary finding of this report suggests that low BDNF levels may predict clinical outcomes in response and warrants further investigation.

Highlights.

Riluzole responders had lower pre-treatment pBDNF and sBDNF at a trend level.

There was no significant correlation between baseline BDNF levels and improvement in depressive symptoms.

Small sample size in longitudinal BDNF samples resulted in unstable means, limiting our ability to draw conclusions about the effects of riluzole treatment on BDNF over time.

Individuals with MDD and low BDNF levels may be more responsive to riluzole treatment.

Acknowledgements:

The authors also acknowledge support from the NIMH, R25MH071584, T32MH062994–15 (STW). This project was supported in part by grant number K12HS023000 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (STW). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. This work was also supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (SJM, CH). Sanofi provided a supply of medication for this study. Finally, we gratefully acknowledge Maurizio Fava, MD, and Gerard Sanacora, MD, PhD, who served as principal investigators of the parent study.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants (R01-MH085055; R01-MH085054; R01-MH085050) and supplements to this grant (R01-MH08505403S1; R01-MH085050–03S1; R01-MH085055–03S1).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: SJM has received funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, PCORI, and Janssen Research & Development. He has received consulting fees from Alkermes, Allergan, Cerecor, Fortress Biotech, Otsuka, and Valeant. He is also supported by the Johnson Family Chair for Research in Psychiatry at Baylor College of Medicine. STW has received consulting fees from Janssen Research & Development. CK, MB, RW and CH have no disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES:

- [1].Depression Fact Sheet. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/, accessed February 7, 2018

- [2].Duman RS, Heninger GR, Nestler EJ, A molecular and cellular theory of depression, Archives of general psychiatry, 54 (1997) 597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pittenger C, Duman RS, Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: a convergence of mechanisms, Neuropsychopharmacology, 33 (2008) 88–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, Krystal JH, Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants, Nature medicine, 22 (2016) 238–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gray J, Milner T, McEwen B, Dynamic plasticity: the role of glucocorticoids, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and other trophic factors, Neuroscience, 239 (2013) 214–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Berton O, McClung CA, DiLeone RJ, Krishnan V, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Graham D, Tsankova NM, Bolanos CA, Rios M, Essential role of BDNF in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in social defeat stress, Science, 311 (2006) 864–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bessa J, Morais M, Marques F, Pinto L, Palha JA, Almeida O, Sousa N, Stress-induced anhedonia is associated with hypertrophy of medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens, Translational psychiatry, 3 (2013) e266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mitra R, Jadhav S, McEwen BS, Vyas A, Chattarji S, Stress duration modulates the spatiotemporal patterns of spine formation in the basolateral amygdala, Proceedings of the national academy of sciences of the United States of America, 102 (2005) 9371–9376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Christoffel DJ, Golden SA, Russo SJ, Structural and synaptic plasticity in stress-related disorders, Reviews in the neurosciences, 22 (2011) 535–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Aguado F, Carmona MA, Pozas E, Aguiló A, Martínez-Guijarro FJ, Alcantara S, Borrell V, Yuste R, Ibañez CF, Soriano E, BDNF regulates spontaneous correlated activity at early developmental stages by increasing synaptogenesis and expression of the K+/Cl-co-transporter KCC2, Development, 130 (2003) 1267–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dijkhuizen PA, Ghosh A, BDNF regulates primary dendrite formation in cortical neurons via the PI3‐kinase and MAP kinase signaling pathways, Developmental Neurobiology, 62 (2005) 278–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Karege F, Vaudan G, Schwald M, Perroud N, La Harpe R, Neurotrophin levels in postmortem brains of suicide victims and the effects of antemortem diagnosis and psychotropic drugs, Molecular Brain Research, 136 (2005) 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Scharfman H, Goodman J, Macleod A, Phani S, Antonelli C, Croll S, Increased neurogenesis and the ectopic granule cells after intrahippocampal BDNF infusion in adult rats, Experimental neurology, 192 (2005) 348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Levine ES, Dreyfus CF, Black IB, Plummer MR, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor rapidly enhances synaptic transmission in hippocampal neurons via postsynaptic tyrosine kinase receptors, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 92 (1995) 8074–8077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bocchio-Chiavetto L, Bagnardi V, Zanardini R, Molteni R, Gabriela Nielsen M, Placentino A, Giovannini C, Rillosi L, Ventriglia M, Riva MA, Serum and plasma BDNF levels in major depression: a replication study and meta-analyses, The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 11 (2010) 763–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sen S, Duman R, Sanacora G, Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor, depression, and antidepressant medications: meta-analyses and implications, Biological psychiatry, 64 (2008) 527–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zou Y-F, Ye D-Q, Feng X-L, Su H, Pan F-M, Liao F-F, Meta-analysis of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism association with treatment response in patients with major depressive disorder, European Neuropsychopharmacology, 20 (2010) 535–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liu R-J, Lee FS, Li X-Y, Bambico F, Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met allele impairs basal and ketamine-stimulated synaptogenesis in prefrontal cortex, Biological psychiatry, 71 (2012) 996–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Risterucci C, Coccurello R, Banasr M, Stutzmann J, Amalric M, Nieoullon A, The metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 antagonist MPEP and the Na+ channel blocker riluzole show different neuroprotective profiles in reversing behavioral deficits induced by excitotoxic prefrontal cortex lesions, Neuroscience, 137 (2006) 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang S-J, Wang K-Y, Wang W-C, Mechanisms underlying the riluzole inhibition of glutamate release from rat cerebral cortex nerve terminals (synaptosomes), Neuroscience, 125 (2004) 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stefani A, Spadoni F, Bernardi G, Differential inhibition by riluzole, lamotrigine, and phenytoin of sodium and calcium currents in cortical neurons: implications for neuroprotective strategies, Experimental neurology, 147 (1997) 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Azbill R, Mu X, Springer J, Riluzole increases high-affinity glutamate uptake in rat spinal cord synaptosomes, Brain research, 871 (2000) 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Katoh-Semba R, Asano T, Ueda H, Morishita R, Takeuchi IK, Inaguma Y, Kato K, Riluzole enhances expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor with consequent proliferation of granule precursor cells in the rat hippocampus, The FASEB Journal, 16 (2002) 1328–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mizuta I, Ohta M, Ohta K, Nishimura M, Mizuta E, Kuno S, Riluzole stimulates nerve growth factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor synthesis in cultured mouse astrocytes, Neuroscience letters, 310 (2001) 117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Du J, Suzuki K, Wei Y, Wang Y, Blumenthal R, Chen Z, Falke C, Zarate CA, Manji HK, The anticonvulsants lamotrigine, riluzole, and valproate differentially regulate AMPA receptor membrane localization: relationship to clinical effects in mood disorders, Neuropsychopharmacology, 32 (2007) 793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Salardini E, Zeinoddini A, Mohammadinejad P, Khodaie-Ardakani MR, Zahraei N, Zeinoddini A, Akhondzadeh S, Riluzole combination therapy for moderate-to-severe major depressive disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Journal of psychiatric research, 75 (2016) 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Coric V, Milanovic S, Wasylink S, Patel P, Malison R, Krystal JH, Beneficial effects of the antiglutamatergic agent riluzole in a patient diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder and major depressive disorder, Psychopharmacology, 167 (2003) 219–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mathew SJ, Gueorguieva R, Brandt C, Fava M, Sanacora G, A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Sequential Parallel Comparison Design Trial of Adjunctive Riluzole for TreatmentResistant Major Depressive Disorder, Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 42 (2017) 2567–2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Katoh‐Semba R, Takeuchi IK, Semba R, Kato K, Distribution of brain‐derived neurotrophic factor in rats and its changes with development in the brain, Journal of neurochemistry, 69 (1997) 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Moghaddam B, Stress preferentially increases extraneuronal levels of excitatory amino acids in the prefrontal cortex: comparison to hippocampus and basal ganglia, Journal of neurochemistry, 60 (1993) 1650–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bartanusz V, Aubry J-M, Pagliusi S, Jezova D, Baffi J, Kiss JZ, Stress-induced changes in messenger RNA levels of N-methyl-D-aspartate and AMPA receptor subunits in selected regions of the rat hippocampus and hypothalamus, Neuroscience, 66 (1995) 247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sapolsky RM, The possibility of neurotoxicity in the hippocampus in major depression: a primer on neuron death, Biological psychiatry, 48 (2000) 755–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fujimura H, Altar CA, Chen R, Nakamura T, Nakahashi T, Kambayashi J.-i., Sun B, Tandon NN, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is stored in human platelets and released by agonist stimulation, THROMBOSIS AND HAEMOSTASIS-STUTTGART-, 87 (2002) 728–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fava M, Evins AE, Dorer DJ, Schoenfeld DA, The problem of the placebo response in clinical trials for psychiatric disorders: culprits, possible remedies, and a novel study design approach, Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 72 (2003) 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mathew SJ, Gueorguieva R, Brandt C, Fava M, Sanacora G, A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Sequential Parallel Comparison Design Trial of Adjunctive Riluzole for TreatmentResistant Major Depressive Disorder, Neuropsychopharmacology, 42 (2017) npp2017106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gourley SL, Espitia JW, Sanacora G, Taylor JR, Antidepressant-like properties of oral riluzole and utility of incentive disengagement models of depression in mice, Psychopharmacology, 219 (2012) 805814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Banasr M, Chowdhury G, Terwilliger R, Newton S, Duman R, Behar K, Sanacora G, Glial pathology in an animal model of depression: reversal of stress-induced cellular, metabolic and behavioral deficits by the glutamate-modulating drug riluzole, Molecular psychiatry, 15 (2010) 501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Salardini E, Zeinoddini A, Mohammadinejad P, Khodaie-Ardakani M-R, Zahraei N, Zeinoddini A, Akhondzadeh S, Riluzole combination therapy for moderate-to-severe major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Journal of psychiatric research, 75 (2016) 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lang UE, Hellweg R, Seifert F, Schubert F, Gallinat J, Correlation between serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor level and an in vivo marker of cortical integrity, Biological psychiatry, 62 (2007) 530535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Karege F, Bondolfi G, Gervasoni N, Schwald M, Aubry J-M, Bertschy G, Low brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels in serum of depressed patients probably results from lowered platelet BDNF release unrelated to platelet reactivity, Biological psychiatry, 57 (2005) 1068–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bus B, Molendijk M, Penninx B, Buitelaar J, Kenis G, Prickaerts J, Elzinga B, Voshaar RO, Determinants of serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor, Psychoneuroendocrinology, 36 (2011) 228239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]