Abstract

Long QT syndrome type 2 (LQT2) is a congenital disease characterized by loss of function mutations in hERG potassium channels (IKr). LQT2 is associated with fatal ventricular arrhythmias promoted by triggered activity in the form of early afterdepolarizations (EADs). We previously demonstrated that intracellular Ca2+ handling is remodeled in LQT2 myocytes. Remodeling leads to aberrant late RyR-mediated Ca2+ releases that drive forward-mode Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) current and slow repolarization to promote reopening of L-type calcium channels and EADs. Forward-mode NCX was found to be enhanced despite the fact that these late releases do not significantly alter the whole-cell cytosolic calcium concentration during a vulnerable period of phase 2 of the action potential corresponding to the onset of EADs. Here, we use a multiscale ventricular myocyte model to explain this finding. We show that because the local NCX current is a saturating nonlinear function of the local submembrane calcium concentration, a larger number of smaller-amplitude discrete Ca2+ release events can produce a large increase in whole-cell forward-mode NCX current without increasing significantly the whole-cell cytosolic calcium concentration. Furthermore, we develop novel insights, to our knowledge, into how alterations of stochastic RyR activity at the single-channel level cause late aberrant Ca2+ release events. Experimental measurements in transgenic LTQ2 rabbits confirm the critical arrhythmogenic role of NCX and identify this current as a potential target for antiarrhythmic therapies in LQT2.

Introduction

Malignant arrhythmias that result in sudden cardiac death (SCD) remain a major cause of death worldwide. Abnormally long Q wave and T wave (QT) intervals have been identified as an important risk factor for SCD in acquired cardiac diseases, including heart failure and myocardial infarction (1, 2). Mutations in 15 different genes have been associated with congenital long QT syndrome. Loss-of-function of KCNH2 encoding the rapidly activating delayed-rectifier K+ channel (IKr) is associated with long QT syndrome type 2 (LQT2), which accounts for over 30% of congenital long QT syndrome cases (2, 3) and results in a high rate of mortality. A large proportion of fatalities in LQT2 patients occur as a result of triggered ventricular tachycardia and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (pVT) evoked by emotional stress or exercise (2, 3, 4). Features of the electrocardiogram such as triggered activity and torsade de pointes are thought to be caused by early afterdepolarizations (EADs) (4, 5), manifested as membrane voltage (Vm) oscillations at the single-myocyte level during the repolarizing phase of the action potential (AP).

To study the phenotype of human arrhythmia, we created a transgenic rabbit model of LQT2 (6) that overexpresses a pore mutant of the human gene KCNH2 (HERG-G628S) in cardiomyocytes to eliminate IKr currents. As a result, these rabbits exhibited prolonged QT interval and high incidence of SCD (>50% at 1 year of age) due to pVT (6). Ex vivo optical mapping used to investigate the underlying substrate of arrhythmia revealed a prominent spatial dispersion of AP duration (APD) and discordant APD alternans (6, 7). The observation of triggered activity in the form of EADs in isolated myocytes under β-adrenergic stimulation has supported the hypothesis that arrhythmia originates at the single-cell level (8, 9).

Normal Ca2+ cycling in cardiomyocytes is maintained by the interplay between the AP and Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) mediated by the ryanodine receptor (RyR) channels. Upon depolarization, a small amount of Ca2+ enters the cell through sarcolemmal L-type calcium channels (LTCCs) to activate RyR clusters that release a much larger amount of Ca2+ to the cytosolic compartment. The sum of those localized Ca2+ release events (Ca2+ sparks) contributes to the transient rise of the whole-cell cytosolic calcium concentration [Ca2+]i (Ca2+ transient). Subsequent removal of intracellular Ca2+ by the electrogenic sarcolemmal Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) current provides additional depolarizing current and can prolong the APD, especially when RyR-mediated SR Ca2+ release termination is not robust. Our previous studies of LQT2 rabbit models showed that Ca2+-mediated communication between RyRs and other Ca2+ transport complexes plays a critical role in EAD formation (10, 11). We reported that the activity of RyRs in rabbit LQT2 ventricular myocytes is enhanced, resulting in a large number of late aberrant SR Ca2+ release events. We proposed that these protracted Ca2+ releases from individual RyR clusters provide a basis for an increased depolarizing NCX current, which suffices to maintain the Vm for a prolonged period of time in a window permissive for reactivation of LTCCs, thereby causing EADs. Our computational modeling validated this hypothesis by demonstrating that late aberrant Ca2+ releases result in a larger-magnitude NCX current during late phase 2 and early phase 3 of the AP, thereby slowing down repolarization and enabling L-type Ca2+ current reactivation during this vulnerable time window, which marks the onset of EADs.

Most computer modeling studies to date have associated EADs with an instability of Vm dynamics driven by reactivation of the L-type Ca2+ current ICa,L during the plateau phase of the AP (12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17). The role of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release in EAD formation was also modeled in the setting of pharmacologically induced LQT2 with a generic block of IKr (18). This study found that reduced SR Ca2+ release can protect against EADs by reducing the Ca2+ transient amplitude and NCX current. In contrast, our previous study of transgenic LQT2 rabbits showed that stabilization of RyR activity by a CAM kinase inhibitor (KN93) increased Ca2+ transient amplitude while at the same time eliminating EADs (10). Our computer-modeling study of LQT2 ventricular myocytes under β-adrenergic stimulation reproduced experimental observations (10) and further showed that in the presence of RyR hyperactivity, the depolarizing NCX current can be significantly larger during late phase 2 and early phase 3 of the AP, thereby promoting reopening of LCCs and EADs. Importantly, modeling revealed that NCX current is enhanced despite SR depletion and reduced Ca2+ transient amplitude (i.e., reduced [Ca2+]i peak during early phase 2 of the AP).

However, the mechanism by which forward-mode NCX current can be enhanced without significantly increasing the whole-cell cytosolic calcium concentration during the vulnerable period of repolarization is still not fully understood. Furthermore, the role of NCX in triggered activity in the setting of LQT2 has not been investigated experimentally. Here, we use a physiologically detailed ventricular myocyte model with spatially distributed Ca2+ release to further elucidate the mechanism of NCX-mediated triggered activity in LQT2 ventricular myocytes, and we validate experimentally our computer-modeling predictions.

Our modeling results show that the local NCX current is a saturating nonlinear function of the local submembrane calcium concentration. Therefore, a larger number of smaller-amplitude Ca2+ release events generated by hyperactive RyRs and reduced SR load can increase whole-cell forward-mode NCX about twofold as much as a smaller number of larger-amplitude Ca2+ release events generated by stable RyRs and normal SR load without significantly increasing calcium transient. Our modeling study further dissects the arrhythmogenic role of two different RyR channel-gating mechanisms that may underlie the increased spark rate observed in permeabilized myocyte experiments (10): increased sensitivity to cleft-calcium concentration, leading to increased RyR open probability (Po) (19), and shortened refractoriness (20), leading to faster recovery of local RyR clusters. We find that the combination of both effects is most effective at potentiating NCX and EADs. Finally, we highlight the role of NCX in triggered activity by demonstrating computationally that partial NCX blockade eliminates EADs. To validate this prediction, we use cellular electrophysiology and confocal Ca2+-imaging study of ventricular myocytes derived from LQT2 hearts with pharmacologically suppressed NCX. The observations confirm the critical role of NCX in EAD initiation.

Methods

Experiments

Myocyte isolation

All procedures were approved by the Rhode Island Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). Ventricular myocytes were isolated from the hearts of transgenic LQT2 (n = 3) female New Zealand white rabbits (3.5 kg) using standard enzymatic digestion procedures. In brief, the heart was excised from euthanized rabbits and perfused for 5–7 min with a nominally Ca2+-free solution containing (in mM) 140 NaCl, 4.4 KCl, 1.5 MgCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 16 taurine, 5 HEPES, 5 pyruvic acid, and 7.5 glucose. Next, the heart was perfused for 10–15 min with the same solution, to which 0.65% collagenase type II (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ) and 0.1% bovine serum albumin were added. The left ventricle was minced, and the cells were dispersed with a glass pipette for 3–5 min in a solution containing (in mM) 45 KCl, 65 K-glutamate, 3 MgSO4, 15 KH2PO4, 16 taurine, 10 HEPES, 0.5 EGTA, and 10 glucose and 1% bovine serum albumin (pH 7.3). The cell suspension was filtered through a 100-μm nylon mesh, plated on laminin-coated coverslips in medium M199, and used within 6–8 h.

Cell electrophysiology and Ca2+ imaging

APs were recorded using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique at 35 ± 2°C using an Axopatch 200B amplifier and DIGIDATA 1322A interface (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) (10). The external solution contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.85 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 5.6 glucose (pH 7.4). Patch pipettes were filled with the following solution (in mM): 90 K-aspartate, 50 KCl, 5 MgATP, 5 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.1 Tris GTP, 10 HEPES, and 0.1 Rhod-2 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR (pH 7.2)). APs were evoked by application of 3-ms-long voltage pulses with amplitude 20% above the threshold level. Intracellular Ca2+ imaging was performed using the Leica SP5 confocal system (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) in a line-scan mode. Rhod-2 was excited by a 543-nm laser and the fluorescence was acquired at 560–660 nm wavelengths. Calcium transients were analyzed using Leica Software, Origin 8.2 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA), and Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MA).

Mathematical modeling

Rabbit ventricular myocyte model

We use a physiologically detailed ventricular myocyte model with Ca2+ cycling coupled to (Vm) dynamics (10) to investigate the ionic mechanisms of EAD formation and elimination in LQT2 myocytes under different conditions. This multiscale model, originally developed by Restrepo et al. (21, 22), bridges the submicron scale of individual Ca2+ release units (CRUs) and the whole cell by simulating a realistically large number of 20,000 diffusively coupled CRUs spatially distributed throughout the cell, with 4 LTCCs colocated with 100 RyRs in each CRU (Fig. S1). It accounts for the stochastic nature of Ca2+ releases by using a Markov description of channel kinetics for both LTCCs and RyRs. In addition, it describes the bidirectional coupling of Ca2+ and Vm dynamics by incorporation of a full set of sarcolemmal currents including ICa,L, INCX, IKs, Ito,f, IK1, and INaK. We exclude IKr to model LQT2 myocytes. This model therefore has the unique capability to explore the effects of alteration of RyR activity at the single-channel level on EAD formation at the whole-cell level.

The model we use is a modification of Restrepo et al. (21, 22) that includes a higher spatial resolution of the diffusive coupling between CRUs, a more quantitative description of Ca2+ buffers, and a 16-state Markov model of LTCCs. The ICa,L model reduces at the whole-cell level to a Hodgkin-Huxley formulation with voltage- and Ca2+-dependent inactivation. This Markov model of LTCCs provides more flexibility for fitting whole-cell experimental measurements of ICa,L, including a larger-window Vm range of this current. We have also modified the Ca2+-dependent activation of the NCX current to be time dependent to account for more recent experiments showing a slower timescale of allosteric Ca2+ activation (23). These changes are detailed in the online supplement of Terentyev et al. (10).

To model the effect of β-adrenergic stimulation with isoproterenol (ISO), we fit the experimental data that results in an increase in the sarcoplasmic reticulumn Ca2+-ATPase uptake rate as well as increases in ICa,L and IKs currents. We incorporate the effect of β-adrenergic stimulation under steady-state conditions to model nontransient EADs that persist on an experimental timescale longer than the timescales of ISO-induced ICa,L and IKs phosphorylation (8).

Computer simulations were carried out by pacing myocytes at 0.25 Hz in accordance with experiments (10) until a steady state was reached. During pacing, whole-cell cytosolic and SR calcium concentrations were recorded, denoted by [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]SR, respectively, along with Vm and individual sarcolemmal currents. In addition, experimental confocal line scans were emulated by recording the local [Ca2+]i along a longitudinal row of CRUs passing through the center of the myocyte and parallel to its long axis.

Model of hyperactive RyRs

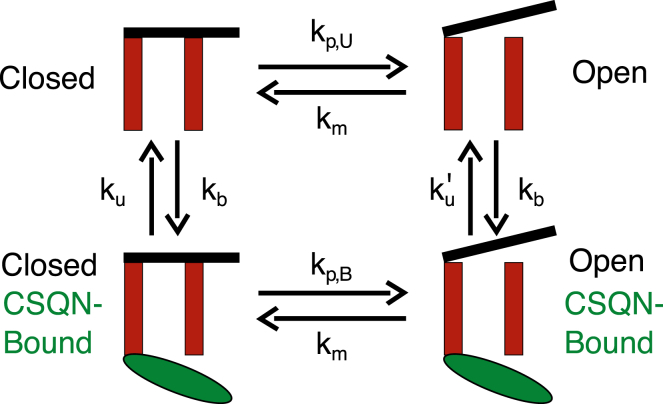

SR release is mediated by 100 RyRs collocated with LCCs in each CRU. Each RyR is described by a four-state model (22) (also shown in Fig. 1), which assumes that luminal Ca2+ regulates the sensitivity of the RyR channels via auxiliary proteins triadin/junctin (T/J) interacting with the luminal Ca2+ buffer calsequestrin (CSQN) (24). This mechanism is incorporated by allowing CSQN to bind to the RyR/T/J complex when Ca2+ is depleted in the JSR and by choosing the RyR closed-to-open transition rate in the CSQN bound state (kp,B) to be much smaller than the one (kp,U) in the CSQN unbound state. The reduced sensitivity in the CSQN bound state both contributes to Ca2+ spark termination and induces a refractory (25, 26) state whereby CSQN must unbind from RyRs before future sparks are possible. Experiments reported a large RyR unitary calcium current under near-physiological ionic conditions (0.35–0.6 pA at 1 mM [Ca2+]JSR) (27, 28), which is ∼10-fold larger than the value assumed in Restrepo et al. (22). Therefore, we follow Sato et al. (29) by using RyR closed-to-open transition rates that produce a maximal open probability around 0.1 (Fig. 2 C). We also introduce an SR load dependence of the closed-to-open rates (kp,U and kp,B) to model the increase of RyR open probability at high [Ca2+]JSR (30), which is not captured by the original Restrepo et al. model (22). In that model, luminal gating of RyR is solely mediated by CSQN binding to the RyR/T/J complex, and the RyR open probability becomes independent of SR load when all RyRs occupy the CSQN unbound state, which occurs for [Ca2+]JSR larger than ∼600 μM (Fig. S2). In this model, RyRs are sensitive to luminal Ca2+ (in addition to being regulated by CSQN binding) as supported by a wide range of experiments (see (31) and references therein).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the four-state model of RyR gating. Transition rates kp,U and kp,B govern the opening of the channel. The transition rate kb, which depends on the amount of Ca2+ bound to CSQN, is accelerated when the load is depleted during SR Ca2+ release. With kp,B much smaller than kp,U, the refractoriness is implemented, which could be tuned by adjusting the relative magnitude of kp,B to kp,U. To see this figure in color, go online.

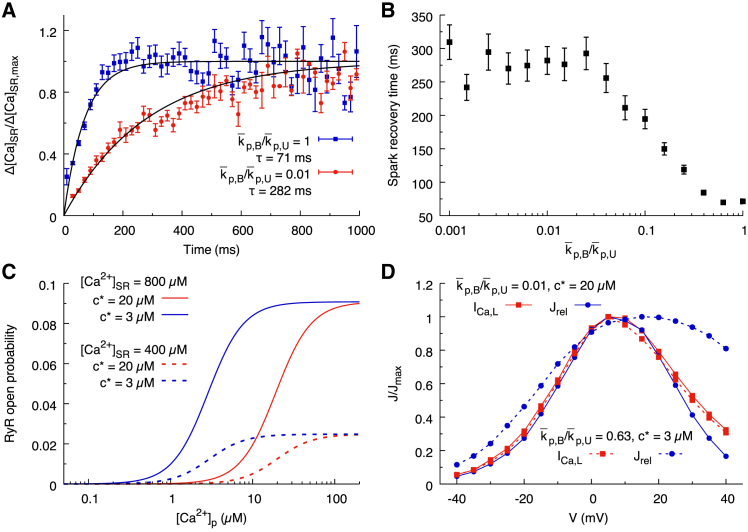

Figure 2.

Effect of altering RyR gating parameters. (A) Spark restitution curves obtained by measuring the relative magnitude of SR Ca blinks after a previous spark occurred in the same CRU for a holding membrane voltage Vm = 0 mV are shown. Blink magnitude is determined by taking the difference of the minimal [Ca2+]JSR and [Ca2+]JSR just before the spark begins. Blink magnitudes are binned into 20-ms intervals. The average values and standard errors are plotted as a function of time since the last spark. The blue and red lines are corresponding to p,B/p,U = 1 and p,B/p,U = 0.01, respectively, with p,U = 4 ms−1 and c∗ = 7 μM. (B) Spark recovery time as a function of p,B/p,U is shown. The data points are extracted from a single exponential fit of spark restitution curves as in (A). (C) The steady-state open probability of RyRs for p,B/p,U = 1 and c∗ = 20 μM (red), c∗ = 3 μM (blue), and for high (solid lines) and low (dashed lines) [Ca2+]JSR is shown. (D) The peak magnitude of ICa,L current (red squares) and SR Ca2+ release transients (blue circles) under voltage clamp steps from holding potential −80 mV to step voltages between −40 and 40 mV for c∗ = 20 μM (solid lines) and c∗ = 3 μM (dashed lines) is shown. ICa,L current peak did not differ between c∗ = 20 μM (solid red line) and c∗ = 3 μM (dashed red line). CICR response has a wider Vm range for c∗ = 3 μM compared to c∗ = 20 μM. To see this figure in color, go online.

The rates kp,U and kp,B (corresponding to k12 and k43, respectively, Restrepo et al. (22)) are given by

| (1) |

and

| (2) |

respectively, where cp = [Ca2+]cleft and cjsr = [Ca2+]JSR are the calcium concentrations in the proximal space (dyadic cleft) and junctional SR (JSR) compartment, respectively. We model RyR hyperactivity both by shifting the open probability of RyRs toward lower cleft-calcium concentration by reducing c∗ as further explained below and by shortening RyR refractoriness. The increase in open probability is consistent with lipid bilayer studies of hyperactive RyRs (19) and the observed increased frequency of Ca2+ sparks in permeabilized LQT2 myocytes in which RyRs are hyperphosphorylated (10).

We can reduce refractoriness by increasing kp,B relative to kp,U. The ratio p,B/p,U controls the relative reduction of RyR opening rate in the CSQN bound state to the unbound state. By increasing this ratio, the channels that have transitioned to the bound state fail to keep the small opening rate and thus fail to suppress the continued sparking of the same CRU.

Refractoriness has previously been characterized by taking repeated nanoscopic measurements of SR Ca2+ blinks (local JSR depletions) (32). This study found that the characteristic timescale for the magnitude of subsequent SR Ca2+ blinks to recover to the original magnitude was much longer than the timescale of the Ca2+ refilling. By replicating these experiments using our model, we produce a quantitative measurement of spark restitution. Fig. 2 A shows that simulations with a larger value of p,B/p,U have reduced refractoriness. When p,B/p,U is smaller than 0.01 (0.01 corresponding to normal RyR activity), the magnitude of SR Ca2+ blinks recovers on a timescale determined by the rate of CSQN unbinding, whereas when p,B/p,U is larger than 0.5, the refractory state does not inhibit RyR opening, and so the magnitude of SR Ca2+ blinks recovers on a timescale determined by the SR refilling time. Fig. 2 B illustrates this trend for values of p,B/p,U ranging between 0.001 and 1.

To model increased Ca2+ sensitivity, we reduce c∗ in Eqs. 1 and 2, which reduces the half maximal effective concentration (EC50) of RyR open probability, thereby increasing the transition rate to the open state at low cleft-calcium concentration cp. This effect is illustrated in Fig. 2 C, in which we plot the RyR open probability as a function of cleft-calcium concentration cp for c∗ = 3 μM and c∗ = 20 μM. For purpose of illustration in Fig. 2 C, we restrict our attention to the limiting case p,B/p,U = 1 (corresponding to ), in which the refractory state does not inhibit RyR openings and the EC50 is given by

| (3) |

By varying the EC50 of RyR opening in this way, there is a measurable effect on the trend of Ca2+-induced-Ca2+-release (CICR) gain. When c∗ is lower, the rate of spark recruitment due to ICa,L is increased above and below 5 mV (the peak voltage for RyR recruitment). The increase of RyR activity when c∗ is reduced is much more potent in the voltage range of EAD onset than for the majority of the AP plateau (Fig. 2 D).

We have previously shown (10) that the mechanism for EAD initiation in this model is largely caused by downstream remodeling of cytosolic Ca2+ cycling, manifested by increased spark frequency in permeabilized myocytes, and has less to do with the direct effect of reduced repolarization current due to the absence of IKr. To investigate the effect of altered Ca2+ cycling, it is useful to distinguish between two extreme cases. The first corresponds to a choice of model parameters with enhanced RyR-mediated SR Ca2+ leak due to both increased sensitivity of RyRs to cytosolic Ca2+ and shortened refractoriness, referred as the “hyperactive” RyR model. This model best reproduces the experimentally observed electrophysiological phenotype of LQT2 under β-adrenergic stimulation with hyperphosphorylated RyRs. The second corresponds to a choice of parameters in which RyR activity is stabilized via Ca2+-calmodulin dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) inhibitor KN93 (10), referred as the “stabilized” RyR model. We have deliberately chosen to only include the stabilizing effect of CaMKII inhibition on RyR activity. Although KN93 may potentially influence other sarcolemmal currents, we are primarily interested here in exploring the effect of abnormal Ca2+ handling on NCX current and EAD formation. In addition to the two above cases of stabilized and hyperactive RyRs, we investigate intermediate cases in which RyR activity is enhanced by increasing channel sensitivity to cytosolic Ca2+ (decreasing c∗) or shortening the refractory period (increasing p,B/p,U). Although there is no known simple way to vary those two parameters individually in the experiment, we exploit the ability to vary them independently in the computational model to gain basic insights into the individual arrhythmogenic roles of increased RyR open probability and shortened refractoriness, which have not been clearly dissected to date.

Results

Role of RyR refractoriness and open probability on AP phenotype

Fig. 3 compares results of simulations of LQT2 myocytes under β-adrenergic stimulation for model parameters corresponding to stabilized RyRs (Fig. 3 A) and increased RyR sensitivity (Fig. 3 B), reduced RyR refractoriness (Fig. 3 C), and both increased sensitivity and reduced refractoriness, denoted as hyperactive RyRs (Fig. 3 D). For all the simulations, the intracellular sodium concentration reaches a steady-state value that varies by less than 3%.

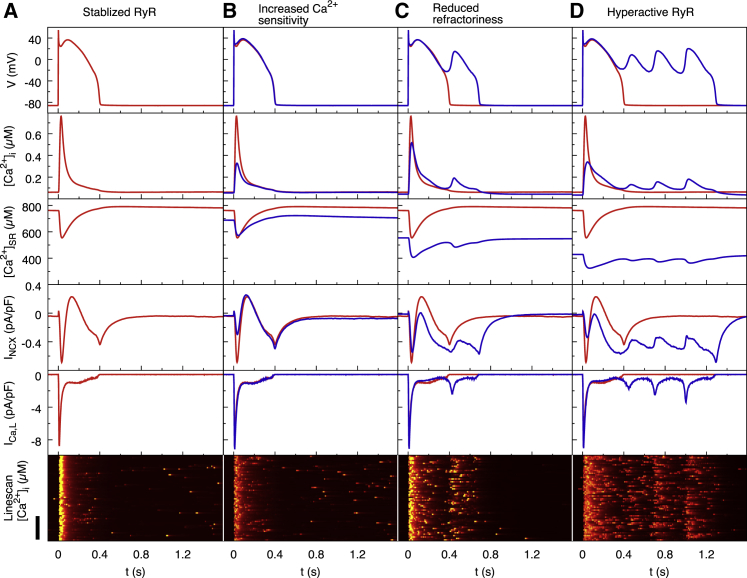

Figure 3.

Computer modeling results of LQT2 myocytes paced at 0.25 Hz under ISO stimulation for the stabilized RyRs control condition (A), only increased Ca2+ sensitivity (B), only reduced refractoriness (C), and the combination of (B) and (C) referred to for brevity as hyperactive RyRs (D). The first row shows Vm traces for representative beats in the steady state. The second row shows whole-cell cytosolic calcium concentration [Ca2+]i. The third row shows SR calcium concentration. The fourth row shows whole-cell average NCX current INCX. The fifth row shows whole-cell long type Ca2+ channel current ICa,L. The sixth row shows a confocal line scan of cytosolic calcium concentration. (A) Stabilized RyRs (c∗ = 7 μM and p,B/p,U = 0.01) with normal Ca2+ transient amplitude and AP are shown. (B) Increased Ca2+ sensitivity (c∗ = 3 μM and p,B/p,U = 0.01) significantly decreases Ca2+ transient amplitude but does not produce EADs. (C) Reduced RyR refractoriness (c∗ = 7 μM and p,B/p,U = 0.6) slightly decreases Ca2+ transient amplitude and produces a single EAD. (D) Both increased Ca2+ sensitivity and reduced refractoriness (hyperactive RyRs with c∗ = 3 μM and p,B/p,U = 0.6) significantly decrease Ca2+ transient amplitude and produce multiple EADs. In all the simulations, p,U is fixed at 4 ms−1. The original code to produce the red and blue lines is available at https://github.com/MingwangZhong/NCX-mediated-EADs-in-LQT2. The red traces in (B)–(D) correspond to the control condition of (A). Scale bar, 30 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

Fig. 3 B shows the effect of increased Ca2+ sensitivity by reducing c∗ from 7 to 3 μM. AP traces in the top panel show that the increased sensitivity causes only a minor deflection in the AP waveform and is insufficient to evoke EADs. The increased RyR open probability results in a reduction in the diastolic SR Ca2+ load (middle panel). Because there is no difference in the luminal dependence of RyR gating, CSQN will bind to the channel and prevent SR Ca2+ release below 550 μM. As a result, the nadir of the SR depletion during systole remains unchanged. This results in a reduced Ca2+ transient amplitude (second panel). Confocal line-scan equivalents show that the number of late Ca2+ sparks during repolarization does not significantly increase when Ca2+ sensitivity is increased in this way (Fig. 3 A versus Fig. 3 B, bottom panels). Consequently, the NCX current is largely unchanged during the repolarization phase (Fig. 3 B, fourth panel).

We then compare the LQT2 model with stabilized RyRs to a model in which RyR refractoriness is hindered by increasing the RyR open rate in the bound state from p,B/p,U = 0.01 to p,B/p,U = 0.6. The top panel of Fig. 3 C shows that without RyR refractoriness, AP repolarization is interrupted with a large EAD, consistent with the results of Terentyev et al. (10). Without CSQN-mediated inactivation of RyRs at low SR load, both the diastolic and systolic SR loads are reduced dramatically (middle panel). Ca2+ transient amplitudes are slightly smaller when refractoriness is reduced, whereas the rate of decay of the Ca2+ transient is noticeably slower (second panel). This is due to the late aberrant Ca2+ sparks that occur during repolarization when refractoriness is reduced, which can be seen in the confocal line scan (bottom panel). When this late Ca2+ release activity occurs, the NCX current shifts toward forward-mode (fourth panel), which slows repolarization and allows ICa,L to recover from inactivation.

When we model both increased Ca2+ sensitivity and reduced RyR refractoriness, the Vm traces show a significantly elongated AP with many EADs (top panel in Fig. 3 D). As before, this model has a reduced SR Ca2+ load (middle panel) but with a much greater reduction in Ca2+ transient amplitude (second panel) and the slower rate of Ca2+ transient decay. Because of the increased Ca2+ sensitivity (Fig. 2 D), CICR during the repolarization phase (−20 to 0 mV) is much more sensitive to ICa,L current, increasing the rate of late aberrant Ca2+ releases during this period (bottom panel of Fig. 3 D; also see Video S1). There is therefore an even greater increase in the forward-mode NCX current that slows repolarization and allows reactivation of ICa,L (Fig. 3 D). This results in the repolarization being interrupted multiple times, leading to multiple EADs.

The movie shows the spatially distributed cytosolic calcium concentration versus time in a 3-dimensional virtual myocyte during an action potential. Also shown on top are corresponding time traces of the whole-cell membrane voltage and cytosolic calcium concentration. Late aberrant Ca2+ releases, which increase forward mode NCX1 current and promote EADs, are highlighted during the time window 100–320 ms.

The interruption to repolarization occurs in a vulnerable Vm window in which LTCCs begin to recover from inactivation but have not yet fully deactivated (15, 33). For time t > 300 ms after initial depolarization, corresponding to late phase 2 of the AP, Vm enters the critical window in which ICa,L begins to recover from inactivation but is still sufficiently activated to allow the current to increase. It is inside this window that Vm in the hyperactive RyR model begins to diverge from the stabilized model toward the first EAD (top panel of Fig. 3 D). The whole-cell NCX current during this time window is larger in the hyperactive RyR model by 110% (−0.55 pA/pF vs. −0.26 pA/pF at t ∼350 ms, Table 1). Although the forward-mode NCX current increase clearly follows the increase in SR Ca2+ release, it is not accompanied by an increase in whole-cell [Ca2+]i, which is traditionally assumed to determine NCX magnitude. Table 1 shows that [Ca2+]i has comparable magnitudes in the hyperactive and stabilized models at t ∼ 350 ms (Table 1) and that the average submembrane calcium concentration [Ca2+]s is only 30% larger in the hyperactive model compared to the stabilized one.

Table 1.

Instantaneous Values at the Whole-Cell Level

| RyR Gating Model | [Ca2+]I (μM) | [Ca2+]s (μM) | Jrel (μMcyt/ms) | Spark Rate (sparks/ms) | INCX (pA/pF) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t = 20 ms | stabilized | 0.69 | 2.41 | 2.31 | 8951 | −0.44 |

| hyperactive | 0.25 | 0.98 | 1.29 | 7671 | −0.13 | |

| t = 322 ms | stabilized | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 107 | −0.26 |

| t = 350 ms | hyperactive | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.11 | 609 | −0.55 |

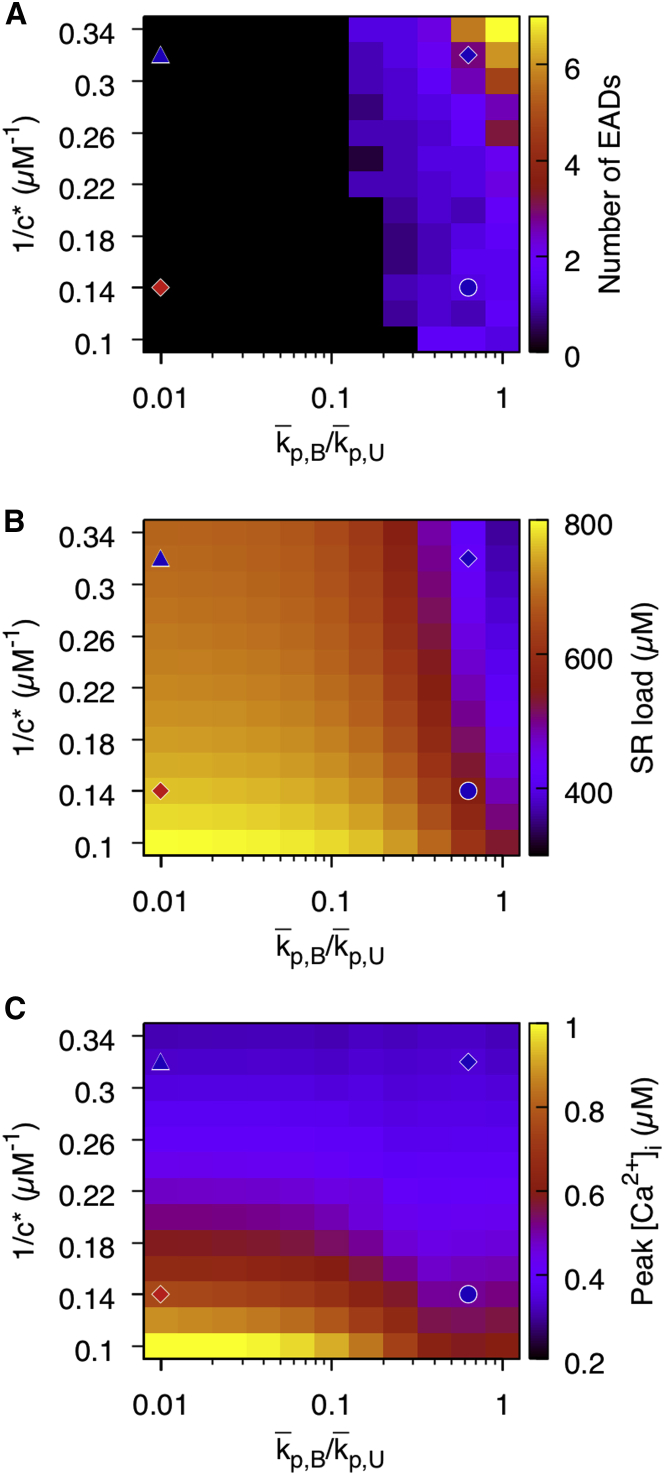

Fig. 4 A maps the effects of varying independently and jointly the two RyR gating parameters 1/c∗ and p,B/p,U (p,U fixed) that control the sensitivity of RyRs to cleft Ca2+ and refractoriness, respectively. The number of EADs increases when both p,B/p,U and 1/c∗ are increased. When we examine the diastolic SR Ca2+ load over the same range of p,B/p,U and 1/c∗ (Fig. 4 B), the load tends to be depleted when these parameters are increased. Fig. 4 C shows that reducing c∗ reduces the Ca2+ transient magnitude, which is consistent with the experimental observations of Terentyev et al. (10) in slowly paced rabbit ventricular myocytes with hyperactive RyRs and addition of ISO. This is because the increased RyR open rate will deplete the diastolic load without allowing the SR nadir during systole to deplete. When p,B/p,U is increased, the effect on Ca2+ transient amplitude is similarly as pronounced because it also increases RyR open probability in the bound state.

Figure 4.

Effect of altering RyR gating on EAD formation and SR release characteristics. (A) The number of EADs as a function of RyR Ca2+ sensitivity, which is increased by decreasing c∗ (increasing 1/c∗), and refractoriness, which is reduced by increasing the ratio p,B/p,U is shown. Both reducing refractoriness and increasing Ca2+ sensitivity produce unstable phenotypes with many EADs. Red diamond, blue triangle, blue circle, and blue diamond denote parameters used in Figs. 3, A–D, respectively. p,U is fixed at 4 ms−1. (B) SR load as a function of 1/c∗ and p,B/p,U is plotted. (C) Ca2+ transient amplitude as a function of 1/c∗ and p,B/p,U is plotted. To see this figure in color, go online.

Fig. 3 only shows results in steady state. As shown in Fig. S8, when RyR sensitivity is suddenly increased by lowering c∗ starting from a diastolic control SR load, EADs form transiently at the first beat even without shortened RyR refractoriness. However, EADs are not sustained because the SR load adjusts to a lower level during subsequent beats because of increased SR leak. A similar transient behavior has been observed in previous studies of Trafford et al. (34) and Venetucci et al. (35). One difference, however, is that those studies were conducted in rat ventricular myocytes with voltage clamped at 0.5 Hz under Ca2+ overload conditions. Under those conditions, spontaneous Ca2+ release is typically manifested in the form of Ca2+ waves causing delayed afterdepolarizations under the combination of ISO and caffeine. Our experiments and those of Terentyev et al. (10) used rabbit ventricular myocytes (either LQT2 rabbit myocytes with leaky RyR + ISO or control rabbit myocytes with caffeine + ISO). In those experiments, Ca2+ cycling instability is manifested in the form of late SR Ca2+ releases triggered by Ca2+ entry through L-type Ca2+ channels at low SR load. Those late releases then drive NCX to slow down repolarization during the AP plateau and cause reactivation of LCCs and EADs.

Mechanism of increased whole-cell forward-mode NCX current without increasing whole-cell cytosolic calcium concentration

As noted earlier, the forward-mode NCX current in the hyperactive RyR model has an ∼110% larger magnitude than in the stabilized RyR model at the time of EAD onset. This increase in NCX current is present even though [Ca2+]i is only slightly increased in the hyperactive model (second panel of Fig. 3 D at t ∼ 350 ms and Table 1). Because RyRs are located in dyads along the T-tubules in the submembrane space, the Ca2+ flux generated by late aberrant releases will preferentially increase [Ca2+]s compared to [Ca2+i (Fig. 5 A). The inset of Fig. 5 A shows that at t ∼ 350 ms, the hyperactive RyR model has a larger total SR Ca2+ release current than the stabilized RyR model by a factor of 3 (0.11 μMcyt/ms vs. 0.04 μMcyt/ms). This larger release current causes the whole-cell averaged [Ca2+]s to be ∼33% larger in the hyperactive RyR model compared to the stabilized RyR model at t ∼ 350 ms shown in Table 1 (the increase in [Ca2+]s is smaller than the increase in SR release current because [Ca2+]s has a finite background value). Importantly, this ∼33% increase in [Ca2+]s cannot account for the ∼110% increase in forward-mode NCX current in a simplistic common-pool model in which whole-cell [Ca2+]s is assumed to drive the whole-cell NCX current. In the more realistic spatially distributed model of Ca2+ release used in this study, the local [Ca2+]s that determines the local NCX current is different in each compartment, varying spatially based on stochastic LTCC openings and SR Ca2+ sparks.

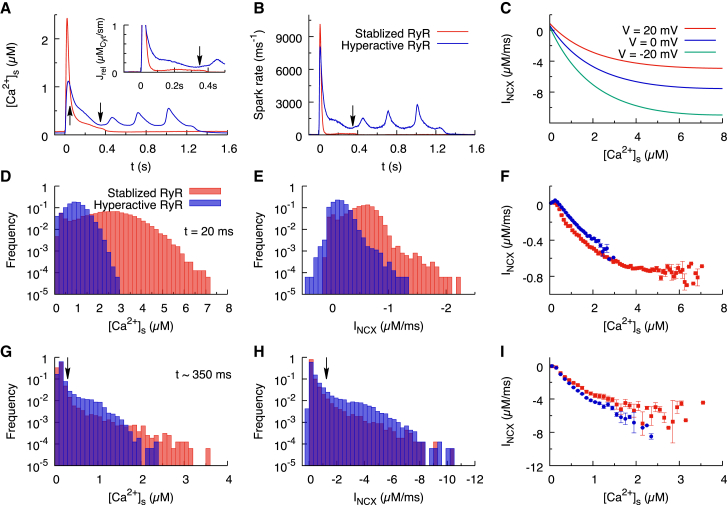

Figure 5.

(A) Calcium concentration in the submembrane space ([Ca2+]s) is shown as a function of time for the stabilized RyR model (red) and the hyperactive RyR model (blue). Arrows indicate the peak calcium transient at t = 20 ms and the EAD onset point at t ∼ 350 ms. The inset is the calcium release current as a function of time. (B) The Ca2+ spark frequency as a function of time is shown, computed by summing all the events satisfying No ≥ 3, where No is the number of open RyRs in a CRU. (C) The local NCX current is shown as a function of local Ca2+ for Vm = −20, 0, and 20 mV, with [Na+]i = 6 mM and allosteric Ca2+ activation ANCX = 0.5. The current saturates at [Ca2+]s ∼ 4 μM. (D) The distribution of local submembrane calcium concentration in each CRU at t = 20 ms is shown. (E) The distribution of local NCX currents in each CRU at t = 20 ms is shown. (F) The relation of the local NCX current to local [Ca2+]s for the stabilized RyR model (red squares) and the hyperactive RyR model (blue circles) at 20 ms, with bin width 0.1 μM, is shown. (G–I) The similar results at t ∼ 350 ms, with Vm at −15.5 mV, are shown. The vertical arrow in (G) indicates the Ca2+ threshold of allosteric activation (0.3 μM), and the vertical arrow in (H) indicates the corresponding NCX current (1.2 μM/ms). To see this figure in color, go online.

To understand the relationship between the increased SR Ca2+ release and the increased NCX current, we examine the spatially distributed nature of Ca2+ release underlying NCX-mediated Ca2+ to Vm voltage signal transduction. For this purpose, we first compare the total spark-firing rates in the hyperactive and stabilized RyR models (Fig. 5 B) and also give their values at the times t = 20 and 350 ms in Table 1, corresponding to the peak of calcium transient and EAD onset, respectively. The whole-cell spark rate at t ∼ 350 ms is around sixfold larger in the hyperactive RyR model (609 sparks/ms) than the stabilized RyR model (107 sparks/ms), even though the whole-cell SR Ca2+ release current is only ∼3-fold larger. This implies that there are a smaller number of large sparks in the stabilized RyR model compared to a greater number of small sparks in the hyperactive RyR model. A smaller number of larger sparks occur in the stabilized model because the larger SR Ca2+ load causes a larger Ca2+ flux during each spark, and sparks are less abundant because RyR channels are less active.

To understand why a larger number of smaller sparks contribute to a larger NCX current in the hyperactive model, we note that the local NCX current is a nonlinear function of the local [Ca2+]s. This nonlinearity stems from the ubiquitous physical limitation on ion transport rate through ion channels, which here causes the NCX current to saturate above [Ca2+]s ∼ 4 μM to a current of −11 μM/ms at Vm = −20 mV and ANCX = 0.5 (Fig. 5 C). As a direct result of this nonlinearity, the whole-cell NCX current cannot be determined by the spatial average of [Ca2+]s compartments as it would be in a “common-pool” model. Furthermore, because NCX saturates at larger [Ca2+]s, a smaller number of large sparks could potentially contribute less to the total NCX current than a greater number of small sparks, even though both sets of sparks contribute to the same whole-cell [Ca2+]s. For this to be true, at least a subset of the larger sparks needs to fall in the range of [Ca2+]s in which NCX saturates (Fig. 5 C).

Therefore, we constructed histograms of local [Ca2+]s and INCX current at t = 20 ms, corresponding to the peak of the calcium transient (Figs. 4 E and 5 D, respectively), and t ∼ 350 ms, corresponding to the critical time of EAD onset (Figs. 4 H and 5 G, respectively). At t = 20 ms, SR Ca2+ releases are highly synchronized, and a large fraction of the CRUs have elevated [Ca2+]s. In the stabilized RyR model, the CRUs have [Ca2+]s as high as 7 μM (the tail of the red distribution in Fig. 5 D), whereas in the hyperactive RyR model, the peak [Ca2+]s is 3 μM (the tail of the blue distribution in Fig. 5 D). At t = 20 ms, the stabilized RyR model has more CRUs with larger peak local NCX current than the hyperactive RyR model (Fig. 5 E), resulting in a larger whole-cell NCX current. The direct relation of the local NCX current to the local [Ca2+]s is shown in Fig. 5 F, which shows the saturation effect for [Ca2+]s larger than 4 μM.

At t ∼ 350 ms, during the critical period in which Vm enters the ICa,L window, the heightened [Ca2+]s in the hyperactive RyR model is being driven by a threefold-larger release current from JSR, which results from a sixfold-larger spark rate (Table 1). This implies that in the stabilized RyR model, the SR Ca2+ flux elevating [Ca2+]s is highly localized to the CRUs undergoing large sparks, whereas in the hyperactive RyR model, there are more sparks with smaller SR Ca2+ flux. With a greater number of CRUs with [Ca2+]s in the range 0.3–1.5 μM (Fig. 5 G), more CRUs have NCX current in the range from −1.2 to −6 μM/ms (blue bars in Fig. 5 H), which results in larger whole-cell average NCX current. In contrast, the stabilized RyR model has a greater number of CRUs with high values of [Ca2+]s that extend into the range in which the nonlinearity of the NCX versus [Ca2+]s relation becomes significant (red squares versus blue squares in Fig. 5 I). We note that the small difference between the red and blue squares in Fig. 5 I, which is due to different amounts of time-dependent allosteric Ca2+ activation of NCX (ANCX), implies that this nonlinearity is predominantly responsible for the 110% larger whole-cell average NCX current for hyperactive compared to stabilized RyRs.

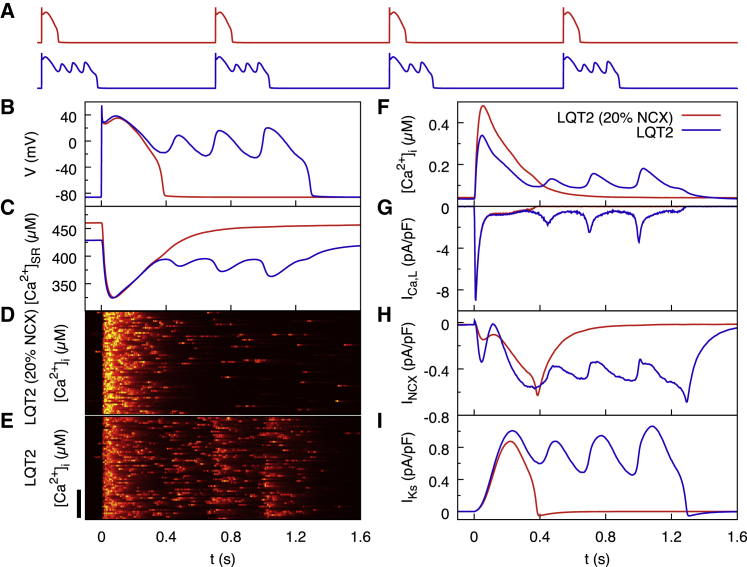

Suppression of EAD formation via reduction of NCX current

To investigate the effect of reducing NCX conductance on EAD formation, we modify the hyperactive RyR model such that the strength of the NCX current (gNCX) is 20% of the normal value (10.5 vs. 52.5 μM/ms). Fig. 6 A shows that in this reduced NCX model, EADs are consistently suppressed. Suppression occurs despite the fact that late aberrant Ca2+ release events during repolarization are still present when NCX conductance is reduced (Fig. 6 D). Fig. 6 B shows that cytosolic Ca2+ content in the reduced NCX model is elevated through all stages of the AP until it repolarizes. This is to be expected, as reduced NCX conductance will slow the rate of Ca2+ extrusion from the myocyte and increase the SR Ca2+ load (Fig. 6 C). Although we find no evidence to suggest that the suppression of EAD onset is due to differences in other Ca2+-dependent sarcolemmal currents including ICa,L (Fig. 6 G) and IKs (Fig. 6 I), we see only a modest decrease in forward-mode depolarizing NCX current in the reduced NCX-conductance model during the critical time window of EAD onset (Fig. 6 H).

Figure 6.

Effect of reducing NCX conductance to 20% of its normal value in the computational model of LQT2 under β-adrenergic stimulation. NCX reduction suppresses EADs despite hyperactive RyRs causing late aberrant Ca2+ releases. (A) Vm traces for four consecutive beats in steady state with reduced (red) and normal (blue) NCX conductance are shown. (B–I) Detailed comparisons for the first beat in (A) of Vm traces (B), the SR calcium concentration (C), confocal line scans for reduced NCX (D) and normal NCX (E), the cytosolic calcium concentration (F), and three key sarcolemmal currents including ICa,L (G), INCX (H), and IKs (I) are shown. The origin of time in (B)–(I) corresponds to the start of the first beat in (A). Scale bar, 30 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

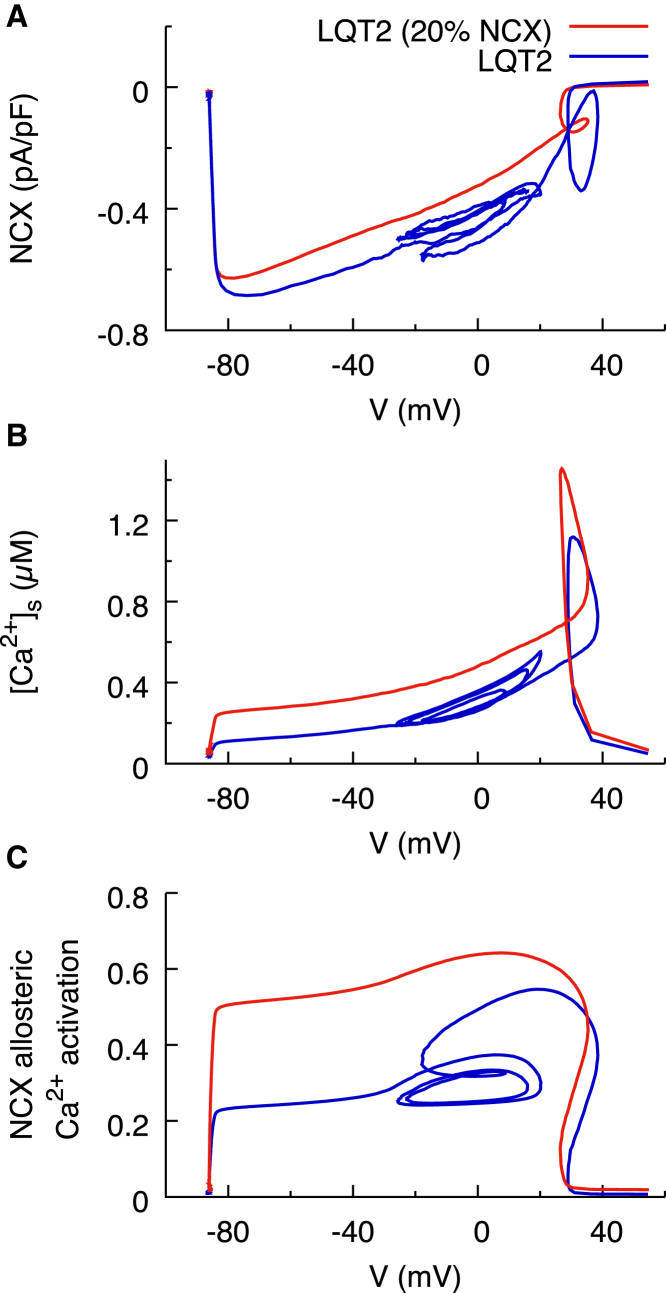

When EADs are suppressed by stabilizing RyR activity, Vm follows a very similar time course to the hyperactive RyR model, slowly deviating only during the critical window after t ∼300 ms (Fig. 3 D). In contrast, when EADs are suppressed via reducing NCX conductance, the time course of Vm begins to deviate from the full NCX model very early in the AP. As a result, comparing the magnitude of the NCX current at the same point in time is misleading. When comparing NCX currents by comparing the magnitude of the current at a given time, it is difficult to quantitatively distinguish the effects of Vm and submembrane Ca2+ on the NCX current. Additionally, as the time course of AP differs, the time differs at which the Vm is within the critical window for ICa,L reactivation. We therefore compare the NCX currents as a function of Vm during pacing (Fig. 7 A). Using this dynamic current versus voltage (I-V) plot to represent the NCX current, we find that within the critical window of Vm (around −20 mV), the reduced conductance NCX model has ∼70% of the magnitude of the normal conductance NCX model. When the NCX current is reduced, the forward mode of this current responsible for Ca2+ extrusion is unable to keep up with Ca2+ influx through ICa,L. As a result, the SR load increases (Fig. 6 C). When NCX conductance is reduced, the higher SR load increases [Ca2+]s during systole and hence both NCX driving force (Fig. 7 B) and Ca2+-dependent allosteric activation of NCX (Fig. 7 C). This model predicts that reduction in NCX conductance is an effective approach to suppress EAD onset for a wide range of ICa,L conductances (Fig. S4). When NCX conductance is reduced in the model, ICa,L conductance must be increased further (from 182 to 240 mmol/cm/C) to reach the threshold for EAD onset.

Figure 7.

Phase plane plots dissecting the Vm and Ca2+ contributions to NCX for the models with reduced (red) and normal (blue) NCX conductance at the same beat corresponding to Fig. 6, B–I. Those plots are intended to show that partial blockade of NCX leads to smaller INCX magnitude together with higher [Ca2+]s and higher allosteric activation of INCX for Vm in the ICa,L window range (Vm ∼ −20 mV). Regions of the plots outside this Vm range are included to represent a complete cycle length but are not directly relevant to the mechanism of EAD suppression by NCX blockade. (A) The dynamic I-V plot of NCX is shown. The hyperactive model with reduced NCX conductance (red) simply repolarizes, whereas the one without reduced NCX conductance (blue) loops back on itself once it reaches −30 mV. The NCX current at the point of EAD onset is larger in the model with normal NCX conductance. (B) The whole-cell average submembrane calcium concentration as a function of Vm is shown. The hyperactive model with reduced NCX conductance has a steep peak because of impaired Ca2+ extrusion leading to increased SR Ca2+ load. (C) Allosteric activation of NCX channels as a function of Vm is shown. Because of the Ca2+ buildup in the reduced conductance NCX model, Ca2+ will activate the channel more rapidly and compensate for the reduced conductance. To see this figure in color, go online.

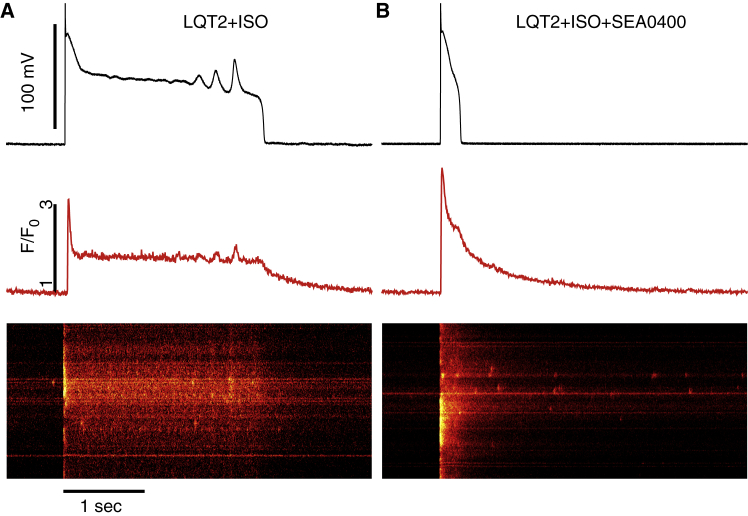

To validate the predictions of computer modeling, we recorded Ca2+ transients in LQT2 myocytes exposed to 50 nM of ISO, a β-adrenergic agonist, for 10–15 min before and after application of 350 nM 2-[4-[(2,5-difluo- rophenyl)methoxy]phenoxy]-5-ethoxyaniline (SEA0400) to partially block NCX (Fig. 8). Without the blocker, myocytes paced at 0.25 Hz experienced significant prolongation of AP and EADs and a protracted tail component of Ca2+ transients (10). Under SEA0400, the peak Ca2+ transient amplitude tends to increase (F/F0 = 4.04 ± 0.44 after vs 3.37 ± 0.69 before SEA0400, n = 3), with confocal line scans continuing to show late intracellular Ca2+ cycling activity. However, AP prolongation was suppressed (from 1404 ± 335 to 158 ± 43 ms) and EADs were fully abolished, in agreement with our computational modeling results with reduced NCX conductance (Fig. 6). AP traces of all LQT2 myocytes treated with SEA0400 are shown in Fig. S5. We note that the spatial heterogeneity of Ca2+ release seen in confocal line scans of LQT2 myocytes (Fig. 8 and previous experiments (10)) is also observed in control rabbit myocytes (10, 36) and is not due to cell damage. In addition, the long plateau of the calcium transient in the experiment (Fig. 8) or the computational model (Fig. 3 D) originates from the fact that, during an EAD, the Vm remains in the window range of the L-type calcium current, as seen by the finite amplitude of ICa,L (blue trace of (D) of Fig. 3 corresponding to ICa,L). The ICa,L current sustains a constant influx of Ca2+ into the cytosol that in turn sustains late SR Ca2+ releases via CICR, as seen in the computed ((D) of Fig. 3) and experimentally measured (Fig. 8; (10)) confocal line scans. In the computational model, ICa,L and SR release contribute ∼10 and 90% to the influx of Ca2+ into the cytosol during the long plateau of the calcium transient, respectively.

Figure 8.

Experimental validation that NCX suppression using NCX blocker SEA0400 eliminates EADs in LQT2 myocytes exposed to 50 nM ISO. Vm traces (black) and corresponding averaged time-dependent profiles (red) and confocal line scan images of Ca2+ transients recorded in current clamped LQT2 myocytes with (A) and without (B) SEA0400 are shown. Despite shortened AP and absence of EADs in myocytes with SEA0400, abnormal Ca2+ activity is evident during repolarization and diastole. To see this figure in color, go online.

EAD mechanism in littermate control myocytes

The important role of RyR activity in EAD initiation can also be shown in littermate control myocytes. Similar to Fig. 3, Fig. S6 shows the simulation results under β-adrenergic stimulation for stabilized RyRs, increased Ca2+ sensitivity, reduced RyR refractoriness, and hyperactive RyRs. Increased RyR activity resulting from the addition of caffeine induces aberrant late Ca2+ releases, which drives the depolarizing forward-mode NCX current, prolongs the action potential duration, and reactivates the ICa,L channels. Moreover, caffeine reduced RyR refractoriness, which allows RyR to reopen after the ICa,L channels are reactivated, generating an EAD.

The effect of pacing frequency

Even though IKs in the hyperactive RyR model tends to eliminate EADs instead of initiating them (Fig. S7 C), it plays an important role in rate-dependent EAD elimination (Fig. S7, A and B). The activation timescale IKs is 0.5 s. Therefore, this current starts to accumulate for stimulation frequency faster than 0.5 Hz. At 1 Hz, EADs are only intermittent. At 2 Hz, the diastolic interval is ∼0.1 s, and the large IKs accumulation suffices to eliminate all EADs.

Discussion

Previous computational modeling studies have revealed many important ionic mechanisms of EAD formation. However, those studies have focused primarily on alterations of sarcolemmal membrane currents. Furthermore, they used common-pool models (37, 38), in which both the Ca2+ flux through LTCCs and the release flux through RyRs feed into the same (whole-cell) compartment and Ca2+ cycling is described by a deterministic set of equations. Our work uses a multiscale ventricular myocyte model to directly probe how alterations of stochastic RyR activity at the single-channel level affect the Ca2+ and voltage dynamics at the whole-cell level. Smaller Ca2+ transient amplitudes have traditionally been associated with a smaller forward-mode NCX current, which would shorten the AP and contribute to suppressing EADs, as predicted in a computer-modeling study of EAD formation in pharmacological LQT2 (18). In contrast, our detailed computational model was able to reproduce the experimental observation that RyR hyperactivity promotes EAD formation while reducing the Ca2+ transient amplitude but promotes late aberrant Ca2+ releases during repolarization (10). Here, we show that those late sparks are a product of modified RyR gating at the single-channel level, which is currently not reproducible in any single-pool model. This modified gating requires both increasing RyR sensitivity to cleft Ca2+ and reducing RyR refractoriness. Although depletion of SR Ca2+ load has been shown to be sufficient for spark termination (39, 40, 41, 42), it remains unclear whether refilling after local SR depletion is the main mechanism of spark refractoriness (20, 43) or whether additional mechanisms (such as CSQN binding to RyR/T/J (24) used in this model) contribute to a delay between refilling and full RyR recovery.

Our modeling results show that NCX current is less depolarizing with hyperactive than with stable RyRs in early phase 2 when [Ca2+]i peaks (Fig. 3 D). However, the NCX current becomes more depolarizing in the hyperactive case within a critical interval of time during late phase 2 to early phase 3, during which the voltage traverses the window for voltage-dependent reactivation of LTCCs. We have previously demonstrated that the higher rate of SR Ca2+ release throughout the vulnerable time window increases Ca2+ flux through the submembrane region, which drives forward-mode NCX current (10). Here, we have shown that increased NCX current may not be predictable using only whole-cell measurements of cytosolic Ca2+ content, as whole-cell average [Ca2+]i in Fig. 3 D insufficiently differs between the hyperactive and stabilized models.

Even in a case of equal total SR Ca2+ release flux, we expect NCX current to be driven more in a hyperactive RyR model with increased RyR activity and depleted SR load than in the stabilized RyR model with higher SR load. In a hyperactive model in which the SR Ca2+ content is depleted, a greater number of smaller individual Ca2+ release events drive a greater NCX current compared to a case with fewer, larger individual sparks, in which NCX current is limited by local current saturation because of limited ion-transport rates (44). This NCX-mediated Ca2+-to-voltage signal transduction mechanism explains how altered Ca2+ handling can promote EAD formation in the setting of reduced SR load with NCX driven primarily by late aberrant Ca2+ releases induced by LTCCs, as opposed to spontaneous Ca2+ waves in the setting of Ca2+ overload in which both early and delayed afterdepolarizations can coexist (45, 46, 47).

The LQT2 model predicts that reducing NCX conductance will result in complete suppression of EADs despite late aberrant Ca2+ releases occurring throughout the repolarization phase. We found that a factor of five reduction in conductance causes only a 20% decrease in the resulting current (Fig. 6). This self-tuning compensatory effect is due to the build-up of cytosolic Ca2+ content, which both increases the driving force of forward-mode NCX and also increases the Ca2+-dependent allosteric activation of the channel.

Identifying changes in currents that are both voltage and time dependent is difficult when investigating the root cause of altered electrophysiological behavior in the setting of a ventricular myocyte with nonlinearly coupled voltage and Ca2+ dynamics. Comparing NCX current at any given instant during repolarization in Fig. 6 H appears to suggest no significant difference between NCX currents in the reduced NCX and full NCX models. By examining NCX behavior as a dynamic I-V plot as in Fig. 7, we exploited the ability to compare the NCX current in each model at equal Vm, revealing a difference in the degree of Ca2+-dependent potentiation of the current. This is critical, as the vulnerable window for EAD formation is the voltage range in which ICa,L under β-adrenergic stimulation has the propensity to spontaneously recover from inactivation and reactivate.

Experiments using SEA0400 to reduce NCX current in LQT2 rabbit myocytes are consistent with computer modeling and validate the role of NCX in EAD onset. This provides a potential pharmacological intervention to treat arrhythmia caused by reduced repolarization reserve exacerbated by irregular SR Ca2+ release. Although we have shown that this arrhythmia may be common in hereditary LQT2, it may also play a role in other human cardiac diseases exhibiting RyR hyperphosphorylation such as heart failure (48). NCX antagonists may therefore be viable as a general intervention for suppressing premature ventricular depolarizations in a variety of human cardiac pathologies.

The mechanism of increased Ca2+ sensitivity of RyRs in LQT2 myocytes was studied in Terentyev et al. (10). Coimmunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that increased phosphorylation of RyRs in LQT2 myocytes versus controls is due to loss of protein phosphatases type 1 and type 2 from the RyR complex. However, the biological mechanism by which loss of function of IKr causes this loss of phosphatases from the RyR complex is not precisely known. We can only speculate that it is linked to remodeling of Ca2+ homeostasis caused by sustained AP prolongation or changes in energetics (49) that shift the phosphatase to other subcellular components.

Limitations

We used a model of CSQN-dependent RyR refractoriness (21, 22), which is supported by experiments showing reduced RyR refractoriness in transgenic mice under-expressing CSQN (50). However, the biological origin of RyR refractoriness is still not fully understood (20, 43). Additionally, we assumed that each CRU in the network has the same number of LTCC and RyRs, thereby neglecting heterogeneities in CRU properties that may be present (40, 51) and could potentially affect the distributions of local Ca2+ spark amplitudes and local NCX currents. Moreover, we have only considered one specific NCX model, and whether similar effects occur with other available NCX models remains to be investigated (52). Finally, we have neglected the spatial variation of Ca2+ within the submicron dyadic space. Although the impact of this variation can in principle be investigated using higher-resolution models (41, 53, 54), we do not expect that its incorporation will fundamentally change the basic mechanism of NCX-mediated subcellular Ca2+ to voltage signal transduction elucidated in our study.

Conclusions

We have investigated the effect of increased RyR channel activity in the form of reduced refractoriness and increased open probability on the genesis of cellular EADs in the setting of LQT2. Our study was motivated by a recent experimental and computational study that linked EAD formation in LQT2 myocytes to RyR hyperactivity (10). However, this study did not explain why forward-mode NCX current can be larger in LQT2 myocytes with hyperactive RyRs than in LQT2 myocytes with stabilized RyRs even though the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration is comparable in the two cases during the vulnerable time period when the Vm traverses the window range for ICa,L reactivation. Our study explains this phenomenon and provides novel mechanistic insights, to our knowledge, into the complex relationship between the spatiotemporal dynamics of intracellular Ca2+ and whole-cell NCX current. Modeling results reveal that, because of the saturation of NCX current as a function of the local submembrane calcium concentration, transduction of elevated Ca2+ to a depolarizing current via forward-mode NCX can be more potent when RyR channels are hyperactive. This is because a larger number of smaller-amplitude discrete Ca2+ release events can produce a large increase in whole-cell forward-mode NCX current, despite reduced SR load, without significantly increasing the whole-cell cytosolic calcium concentration, [Ca2+]i. As a result, [Ca2+]i is not the sole determinant of whole-cell NCX current magnitude as assumed in traditional common-pool models of Ca2+ cycling. This highlights the importance of detailed multiscale modeling in correctly reproducing the behavior of cardiac Ca2+ cycling and excitation-contraction coupling. In addition, we have validated the role of NCX in EAD formation in LQT2 by single-cell electrophysiological experiments. The results confirm the modeling predictions that reduced NCX conductance abolishes EADs and suggests that pharmacological alteration of NCX may be a potential therapeutic intervention to treat pVT in diseases accompanied by RyR hyperactivity and reduced repolarization reserve, including LQT2. Future studies that image Ca2+ activity in myocytes in intact heart remain needed to investigate the relevance of our findings to arrhythmias at the organ scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.R. and A.K.; Methodology, C.M.R. and D.T.; Software, M.Z. and C.M.R.; Formal Analysis, M.Z. and C.M.R.; Investigation, M.Z., C.M.R., and D.T.; Writing—Original Draft, C.M.R.; Writing, Review and Editing, M.Z., C.M.R., D.T., G.K., and A.K.; Supervision, A.K. and G.K.; Funding Acquisition, G.K. and D.T.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Toshio Matsuda and Dr. Akemichi Baba for providing the SEA0400.

This work was supported by NIH RO1 HL0460005-23 and RO1 HL110791-01A1 to G.K. and RO1 HL121796 to D.T.

Editor: James Keener.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, eight figures, three tables, and one video are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)30926-3.

Supporting Information

References (55, 56, 57) appear in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Day C.P., McComb J.M., Campbell R.W. QT dispersion: an indication of arrhythmia risk in patients with long QT intervals. Br. Heart J. 1990;63:342–344. doi: 10.1136/hrt.63.6.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Priori S.G., Schwartz P.J., Cappelletti D. Risk stratification in the long-QT syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1866–1874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerrone M., Priori S.G. Genetics of sudden death: focus on inherited channelopathies. Eur. Heart J. 2011;32:2109–2118. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antzelevitch C. Ionic, molecular, and cellular bases of QT-interval prolongation and torsade de pointes. Europace. 2007;9(Suppl 4):iv4–iv15. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss J.N., Garfinkel A., Qu Z. Early afterdepolarizations and cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1891–1899. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunner M., Peng X., Koren G. Mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden death in transgenic rabbits with long QT syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:2246–2259. doi: 10.1172/JCI33578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziv O., Morales E., Choi B.-R. Origin of complex behaviour of spatially discordant alternans in a transgenic rabbit model of type 2 long QT syndrome. J. Physiol. 2009;587:4661–4680. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.175018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu G.X., Choi B.R., Koren G. Differential conditions for early after-depolarizations and triggered activity in cardiomyocytes derived from transgenic LQT1 and LQT2 rabbits. J. Physiol. 2012;590:1171–1180. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.218164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Z., Wen H., Xie L.H. Revisiting the ionic mechanisms of early afterdepolarizations in cardiomyocytes: predominant by Ca waves or Ca currents? Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012;302:H1636–H1644. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00742.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terentyev D., Rees C.M., Koren G. Hyperphosphorylation of RyRs underlies triggered activity in transgenic rabbit model of LQT2 syndrome. Circ. Res. 2014;115:919–928. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.305146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odening K.E., Choi B.R., Koren G. Estradiol promotes sudden cardiac death in transgenic long QT type 2 rabbits while progesterone is protective. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:823–832. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng J., Rudy Y. Early afterdepolarizations in cardiac myocytes: mechanism and rate dependence. Biophys. J. 1995;68:949–964. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80271-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clancy C.E., Rudy Y. Cellular consequences of HERG mutations in the long QT syndrome: precursors to sudden cardiac death. Cardiovasc. Res. 2001;50:301–313. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lerma C., Krogh-Madsen T., Glass L. Stochastic aspects of cardiac arrhythmias. J. Stat. Phys. 2007;128:347–374. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran D.X., Sato D., Qu Z. Bifurcation and chaos in a model of cardiac early afterdepolarizations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:258103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.258103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qu Z., Xie L.H., Weiss J.N. Early afterdepolarizations in cardiac myocytes: beyond reduced repolarization reserve. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013;99:6–15. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie Y., Grandi E., Bers D.M. β-adrenergic stimulation activates early afterdepolarizations transiently via kinetic mismatch of PKA targets. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2013;58:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parikh A., Mantravadi R., Salama G. Ranolazine stabilizes cardiac ryanodine receptors: a novel mechanism for the suppression of early afterdepolarization and torsades de pointes in long QT type 2. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:953–960. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porta M., Zima A.V., Fill M. Single ryanodine receptor channel basis of caffeine’s action on Ca2+ sparks. Biophys. J. 2011;100:931–938. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belevych A.E., Terentyev D., Györke S. Shortened Ca2+ signaling refractoriness underlies cellular arrhythmogenesis in a postinfarction model of sudden cardiac death. Circ. Res. 2012;110:569–577. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.260455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Restrepo J.G., Karma A. Spatiotemporal intracellular calcium dynamics during cardiac alternans. Chaos. 2009;19:037115. doi: 10.1063/1.3207835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Restrepo J.G., Weiss J.N., Karma A. Calsequestrin-mediated mechanism for cellular calcium transient alternans. Biophys. J. 2008;95:3767–3789. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ginsburg K.S., Weber C.R., Bers D.M. Cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger: dynamics of Ca2+-dependent activation and deactivation in intact myocytes. J. Physiol. 2013;591:2067–2086. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.252080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Györke I., Hester N., Györke S. The role of calsequestrin, triadin, and junctin in conferring cardiac ryanodine receptor responsiveness to luminal calcium. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2121–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74271-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobie E.A., Song L.S., Lederer W.J. Local recovery of Ca2+ release in rat ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. 2005;565:441–447. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sobie E.A., Song L.S., Lederer W.J. Restitution of Ca(2+) release and vulnerability to arrhythmias. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2006;17(Suppl 1):S64–S70. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mejía-Alvarez R., Kettlun C., Fill M. Unitary Ca2+ current through cardiac ryanodine receptor channels under quasi-physiological ionic conditions. J. Gen. Physiol. 1999;113:177–186. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kettlun C., González A., Fill M. Unitary Ca2+ current through mammalian cardiac and amphibian skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor Channels under near-physiological ionic conditions. J. Gen. Physiol. 2003;122:407–417. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato D., Bers D.M. How does stochastic ryanodine receptor-mediated Ca leak fail to initiate a Ca spark? Biophys. J. 2011;101:2370–2379. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qin J., Valle G., Fill M. Luminal Ca2+ regulation of single cardiac ryanodine receptors: insights provided by calsequestrin and its mutants. J. Gen. Physiol. 2008;131:325–334. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones P.P., Guo W., Chen S.R.W. Control of cardiac ryanodine receptor by sarcoplasmic reticulum luminal Ca2. J. Gen. Physiol. 2017;149:867–875. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201711805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brochet D.X., Yang D., Cheng H. Ca2+ blinks: rapid nanoscopic store calcium signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:3099–3104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500059102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ming Z., Nordin C., Aronson R.S. Role of L-type calcium channel window current in generating current-induced early afterdepolarizations. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 1994;5:323–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1994.tb01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trafford A.W., Díaz M.E., Eisner D.A. Modulation of CICR has no maintained effect on systolic Ca2+: simultaneous measurements of sarcoplasmic reticulum and sarcolemmal Ca2+ fluxes in rat ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. 2000;522:259–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venetucci L.A., Trafford A.W., Eisner D.A. Increasing ryanodine receptor open probability alone does not produce arrhythmogenic calcium waves: threshold sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content is required. Circ. Res. 2007;100:105–111. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000252828.17939.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fowler E.D., Kong C.H.T., Cannell M.B. Late Ca2+ sparks and ripples during the systolic Ca2+ transient in heart muscle cells. Circ. Res. 2018;122:473–478. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahajan A., Shiferaw Y., Weiss J.N. A rabbit ventricular action potential model replicating cardiac dynamics at rapid heart rates. Biophys. J. 2008;94:392–410. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.98160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shannon T.R., Wang F., Bers D.M. A mathematical treatment of integrated Ca dynamics within the ventricular myocyte. Biophys. J. 2004;87:3351–3371. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vierheller J., Neubert W., Chamakuri N. A multiscale computational model of spatially resolved calcium cycling in cardiac myocytes: from detailed cleft dynamics to the whole cell concentration profiles. Front. Physiol. 2015;6:255. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sobie E.A., Dilly K.W., Jafri M.S. Termination of cardiac Ca(2+) sparks: an investigative mathematical model of calcium-induced calcium release. Biophys. J. 2002;83:59–78. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75149-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker M.A., Williams G.S.B., Winslow R.L. Superresolution modeling of calcium release in the heart. Biophys. J. 2014;107:3018–3029. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song Z., Karma A., Qu Z. Long-lasting sparks: multi-metastability and release competition in the calcium release unit network. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016;12:e1004671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramay H.R., Liu O.Z., Sobie E.A. Recovery of cardiac calcium release is controlled by sarcoplasmic reticulum refilling and ryanodine receptor sensitivity. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011;91:598–605. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weber C.R., Ginsburg K.S., Bers D.M. Allosteric regulation of Na/Ca exchange current by cytosolic Ca in intact cardiac myocytes. J. Gen. Physiol. 2001;117:119–131. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burashnikov A., Antzelevitch C. Late-phase 3 EAD. A unique mechanism contributing to initiation of atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2006;29:290–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie L.H., Weiss J.N. Arrhythmogenic consequences of intracellular calcium waves. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009;297:H997–H1002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00390.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shiferaw Y., Aistrup G.L., Wasserstrom J.A. Intracellular Ca2+ waves, afterdepolarizations, and triggered arrhythmias. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012;95:265–268. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marx S.O., Reiken S., Marks A.R. PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell. 2000;101:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jindal H.K., Merchant E., Koren G. Proteomic analyses of transgenic LQT1 and LQT2 rabbit hearts elucidate an increase in expression and activity of energy producing enzymes. J. Proteomics. 2012;75:5254–5265. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Terentyev D., Viatchenko-Karpinski S., Györke S. Calsequestrin determines the functional size and stability of cardiac intracellular calcium stores: Mechanism for hereditary arrhythmia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11759–11764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932318100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soeller C., Crossman D., Cannell M.B. Analysis of ryanodine receptor clusters in rat and human cardiac myocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14958–14963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703016104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chu L., Greenstein J.L., Winslow R.L. Modeling Na+-Ca2+ exchange in the heart: Allosteric activation, spatial localization, sparks and excitation-contraction coupling. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016;99:174–187. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weinberg S.H., Smith G.D. The influence of Ca2+ buffers on free [Ca2+] fluctuations and the effective volume of Ca2+ microdomains. Biophys. J. 2014;106:2693–2709. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wieder N., Fink R., von Wegner F. Exact stochastic simulation of a calcium microdomain reveals the impact of Ca2+ fluctuations on IP3R gating. Biophys. J. 2015;108:557–567. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terentyev D., Kubalova Z., Gyorke S. Modulation of SR Ca release by luminal Ca and calsequestrin in cardiac myocytes: effects of CASQ2 mutations linked to sudden cardiac death. Biophys. J. 2008;95:2037–2048. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.128249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Restrepo J.G., Weiss J.N., Karma A. Calsequestrin-mediated mechanism for cellular calcium transient alternans. Biophys. J. 2018;114:2024–2025. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shannon T.R., Ginsburg K.S., Bers D.M. Potentiation of fractional sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release by total and free intra-sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium concentration. Biophys. J. 2000;78:334–343. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76596-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The movie shows the spatially distributed cytosolic calcium concentration versus time in a 3-dimensional virtual myocyte during an action potential. Also shown on top are corresponding time traces of the whole-cell membrane voltage and cytosolic calcium concentration. Late aberrant Ca2+ releases, which increase forward mode NCX1 current and promote EADs, are highlighted during the time window 100–320 ms.