Methylation of cytosine residues exerts a critical role in silencing gene transcription. Importantly, DNA methylation patterns are often altered in cancer, with many tumors showing site-specific gain of methylation marks in a background of global hypomethylation (1).

In PNAS, Stone et al. (2) show in an ovarian cancer model that treatment with the demethylating agent 5-azacytidine resulted in reexpression of human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs), activation of type I IFN signaling, and increased CD8+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment. These data provide important insights into the role of DNA methylation in suppressing immunogenic pathways and provide additional support for the notion that hypomethylation can resculpt the host antitumor response through derepression of HERV and activation of type I IFN signaling (3, 4).

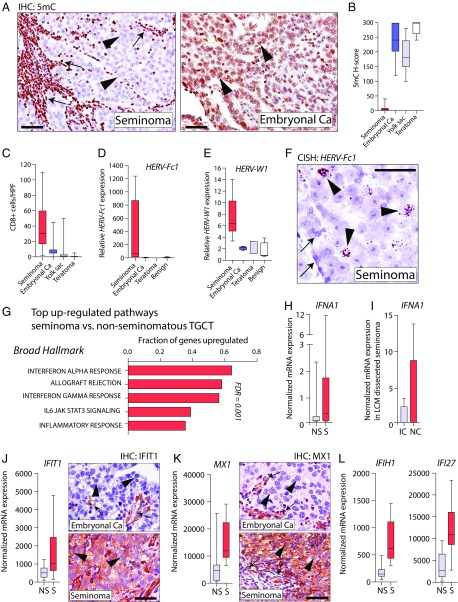

We hypothesized that such elevated HERV expression and type I IFN signaling are also present in tumors that are characterized by constitutive DNA hypomethylation. Seminoma, a type of testicular germ cell tumor (TGCT), provides an opportunity to test this hypothesis. The majority of seminomas are nearly devoid of methylated cytosines (5, 6) and frequently exhibit a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate (7, 8). In contrast, nonseminomatous TGCT, including embryonal carcinoma, teratoma, yolk sac tumors, and choriocarcinoma, show methylation levels in the range of normal tissues and no significant immune cell infiltrate (6, 7). To explore the connection between hypomethylation and the immune infiltrate in TGCTs, we characterized DNA methylation levels in situ and immune infiltrates in a series of TGCTs and observed profound DNA hypomethylation and an increased number of CD8+ lymphocytes in the seminomas compared with nonseminomatous TGCT (Fig. 1 A–C). This pronounced hypomethylation in seminomas was accompanied by significantly increased expression of HERVs in seminomas compared with other TGCTs, and RNA in situ hybridization revealed that HERV expression was restricted to neoplastic cells in seminomas (Fig. 1 D–F). Further expression analysis using the nanostring PanCancer Immune Profiling Panel in a cohort of TGCTs, including seminoma, embryonal carcinoma, and teratoma, showed IFN-alpha response as the top up-regulated pathway in seminomas. Targeted analysis further revealed increased expression of IFN-alpha (IFNA1) in seminomas compared with nonseminomatous TGCTs (Fig. 1 G and H). Importantly, IFNA1 expression in seminoma was greatly enriched in neoplastic cells compared with separately microdissected inflammatory cells, suggesting that the IFN response was originating from the neoplastic cells (Fig. 1I). Finally, analysis of genes involved in IFN response and viral defense that were shown to be up-regulated by 5-azacytidine (3, 4) were consistently expressed at higher levels in seminomas compared with nonseminomatous TGCT, with their expression being predominantly localized within neoplastic seminoma cells (Fig. 1 J–L).

Fig. 1.

(A) Micrographs of TGCTs immunolabeled for 5-methyl-cytosine (5mC) in which seminoma cells (arrowheads) and intratumoral lymphocytes (arrows) are shown. Ca, carcinoma(s). (B) Global 5mC levels in 22 seminomas, 14 embryonal Ca, 11 yolk sac tumors, and 9 teratomas. (C) CD8+ T cells in TGCTs. HPF, high-power field. (D and E) Expression of HERV-Fc1, HERV-W1 seminoma (n = 9), embryonal Ca (n = 7), and teratoma (n = 3), as well as benign testis (n = 3). (F) In situ detection of HERV-Fc1 is restricted to neoplastic seminoma cells (arrowheads) and not present in adjacent benign cells (arrows). (G) Top up-regulated gene sets in seminoma vs. nonseminomatous TGCTs. (H) IFNA1 expression in seminoma (S) and nonseminomatous TGCT (NS). (I) IFNA1 expression in tumor-associated inflammatory cells (IC) and neoplastic cells (NC) isolated by laser capture microdissection (LCM) of seminoma tissues. (J–L) Expression of IFN/viral response-related genes. Strong immunoreactivity for IFIT1 and MX1 is present in neoplastic cells (arrowheads) in seminoma, and focal reactivity is present in stromal cells and a subset of tumor-associated lymphocytes (arrows). (Scale bars: 100 μm.)

These data suggest that constitutive global hypomethylation as observed in seminoma is associated with HERV expression, increased type I IFN signaling, and CD8+ T cell infiltrates, providing a plausible mechanism for the dense lymphocytic infiltrates characteristically seen in seminoma.

Amplifying on the findings from Stone et al. (2), we propose that marked DNA hypomethylation, whether tumor-intrinsic or pharmacologically induced, can render tumors more immunogenic and could be used as a potential biomarker for cancer immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by NIH/National Cancer Institute Grant P30CA006973, the Commonwealth Foundation, and the Bloomberg∼Kimmel Institute. M.C.H. is the recipient of the Fred and Janet Sanfilippo Research Award.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: C.G.D. has served as a paid consultant to Roche Genentech, Merck, and Novartis, and has received sponsored research funding from the Bristol-Myers Squibb International Immuno-Oncology Network and from Janssen, Inc. A.M.D.M. has received sponsored research funding from Janssen, Inc.

References

- 1.Baylin SB, Jones PA. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome - biological and translational implications. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:726–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stone ML, et al. Epigenetic therapy activates type I interferon signaling in murine ovarian cancer to reduce immunosuppression and tumor burden. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E10981–E10990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1712514114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiappinelli KB, et al. Inhibiting DNA methylation causes an interferon response in cancer via dsRNA including endogenous retroviruses. Cell. 2015;162:974–986. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roulois D, et al. DNA-demethylating agents target colorectal cancer cells by inducing viral mimicry by endogenous transcripts. Cell. 2015;162:961–973. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peltomäki P. DNA methylation changes in human testicular cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1096:187–196. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(91)90004-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Netto GJ, et al. Global DNA hypomethylation in intratubular germ cell neoplasia and seminoma, but not in nonseminomatous male germ cell tumors. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:1337–1344. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng L, Lyu B, Roth LM. Perspectives on testicular germ cell neoplasms. Hum Pathol. 2017;59:10–25. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siska PJ, et al. Deep exploration of the immune infiltrate and outcome prediction in testicular cancer by quantitative multiplexed immunohistochemistry and gene expression profiling. OncoImmunology. 2017;6:e1305535. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1305535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]