Abstract

Background and objectives

Bloodstream infection rates of patients on hemodialysis with catheters are greater than with other vascular accesses and are an important quality measure. Our goal was to compare relative bloodstream infection rates of patients with and without catheters as a quality parameter among the facilities providing hemodialysis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We used CROWNWeb and National Healthcare Safety Network data from all 179 Medicare facilities providing adult outpatient hemodialysis in New England for >6 months throughout 2015–2016 (mean, 12,693 patients per month). There was a median of 60 (interquartile range, 43–93) patients per facility, with 17% having catheters.

Results

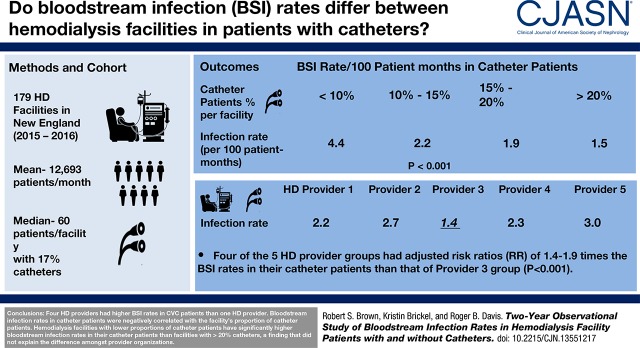

Among the five batch-submitting dialysis organizations, the bloodstream infection rate in patients with a catheter in four organizations had adjusted risk ratios of 1.44 (95% confidence interval, 1.07 to 1.93) to 1.91 (95% confidence interval, 1.39 to 2.63) times relative to the reference dialysis provider group (P<0.001). The percentage of catheters did not explain the difference in bloodstream infection rates among dialysis provider organizations. The bloodstream infection rates in patients with a catheter were negatively correlated with the facility’s proportion of this patient group. Facilities with <10%, 10%–14.9%, 15%–19.9%, and ≥20% catheter patients had bloodstream infection rates of 4.4, 2.2, 1.9, and 1.5 per 100 patient-months, respectively, in that patient group (adjusted P<0.001). This difference was not seen in patients without catheters. There was no effect of facility patient census or season of the year.

Conclusions

A study of the adult outpatient hemodialysis facilities in New England in 2015–2016 found that four dialysis provider groups had significantly higher bloodstream infection rates in patients with a catheter than the best-performing dialysis provider group. Hemodialysis facilities with lower proportions of patients with a catheter have significantly higher bloodstream infection rates in this patient group than facilities with >20% catheters, a finding that did not explain the difference among provider organizations.

Keywords: hemodialysis access, risk factors, Bloodstream infection, hemodialysis catheter, quality care, dialysis providers, Odds Ratio, renal dialysis, Risk, Outpatients, Censuses, Catheter-Related Infections, Bacteremia, Medicare, Catheters

Introduction

It is well recognized that patients with ESKD receiving hemodialysis with a central venous catheter as their vascular access experience higher rates of bloodstream infection (1–3). Whereas the bloodstream infection rate reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for 2014 in patients with an arteriovenous fistula was 0.26 per 100 patient-months, in those with a catheter, it was 2.16 (4,5). Reports have noted considerable variability between facilities and infection control interventions can reduce facility bloodstream infection rates (6–10). These data, and the higher mortality rate of patients with a catheter (3,11–13), have prompted the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to consider both the proportion of patients with a catheter and the bloodstream infection rates in hemodialysis facilities as quality measures in the ESKD Quality Incentive Program (QIP) (14). CMS will penalize hemodialysis facilities with higher percentages of patients with catheters or higher bloodstream infection rates through the risk of reduced Medicare reimbursement (14) and lower five-star ratings (15). Furthermore, the CDC has initiated a partnership among organizations, including dialysis providers, the “Making Dialysis Safer for Patients Coalition,” whose goal is to “improve adherence to evidence-based recommendations” to prevent bloodstream infections in patients receiving hemodialysis (16). We noted wide variations of the bloodstream infection rates in patients with catheters among hemodialysis facilities in New England, prompting a study of bloodstream infection rates in 2015 and 2016.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Data Sources

We obtained data for each month of the calendar years 2015 and 2016 from CROWNWeb, as well as bacteremic bloodstream infection data from the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). Each Medicare facility that provides outpatient maintenance hemodialysis for patients with ESKD in New England is required to file data on all patients in their facility each month. We excluded Veterans Administration and pediatric facilities, and four facilities that had data for fewer than six of the 24 months. Three facilities were missing monthly observation data on the number of patients with catheters and that month’s data were removed from the analysis. The monthly data by facility included the following: (1) total number of patients receiving hemodialysis recorded on the first two working days of the month, (2) number of patients with catheters, (3) number of bloodstream infections recorded by the last day of the month for patients with all vascular access types and for patients dialyzed with a catheter at the time of the reported positive blood culture (obtained in the facility or during the first 48 hours of hospitalization), and (4) the batch-submitting organization, i.e., three large dialysis provider groups that own and operate multiple hemodialysis facilities (DaVita Kidney Care, Dialysis Clinic, Inc., and Fresenius Medical Care), and two independently operated groups of facilities, one with data submission provided to CROWNWeb by the National Renal Administrators Association, and the remaining independent facilities, which included smaller organizations and single units. We identified 11 hospital-based facilities providing outpatient maintenance dialysis. All data were obtained from the IPRO ESRD Network of New England contract through data use agreements that include maintenance of confidentiality. Because all data were analyzed on the basis of the facility monthly reports of total numbers of unidentified patients, the hospital institutional review board determined that this study did not constitute human subjects research and did not require their approval.

Statistical Analyses

The data were analyzed to calculate bloodstream infection rates as defined by the CDC Dialysis Event Protocol (17) for patients with all vascular accesses, catheter accesses, and noncatheter accesses (arteriovenous fistulae and grafts) in each facility each month. The CDC Dialysis Event Protocol defines the bloodstream infection rate as the number of bacteremic events (with one or more positive blood cultures within 21 days considered to be a single event) divided by the number of patients in the facility multiplied by 100. As does the CDC, we summarized bloodstream infection rates by the means (±SD), and facility census data by medians with quartiles 1 and 3 (interquartile range [IQR]).We categorized the catheter proportions by facilities with <10%, 10%–14.9%, 15%–19.9%, and ≥20% catheter patients each month, and presented raw bloodstream infection numbers and rates for each category. In addition, we assessed bloodstream infection rates for facilities with <25, 25–49, 50–99, and ≥100 total patients, for the five batch-submitting organizations and the hospital-based outpatient facilities, and the four seasons of the year (defined as winter, January–March; spring, April–June; summer, July–September; and fall, October–December).

We fit log binomial regression models to evaluate the association between bloodstream infection rates and facility characteristics using generalized estimating equations methods with a compound symmetry correlation structure to account for the correlation of the monthly observations within the centers adjusting for facility catheter percentage, patients per facility, batch-submitting organizations, hospital-based facilities, and season of the year. We report Wald P values, adjusted risk ratios (to account for potential confounding by any of the other covariates in the model), and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for all patients, patients with catheters, and patients without catheters. We fit a generalized estimating equations model with an identity link to estimate the average proportion of patients with catheters by batch-submitting organization. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software (version 9.4 for Windows; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Total Study Population

There were 170 facilities with 24 months of data and nine facilities with 6–23 months of data that provided outpatient maintenance hemodialysis in New England in 2015–2016, yielding 4203 total monthly observations with an average of 12,693 patients per month. There was a median of 60 (IQR, 43–93) patients per facility, of which a median of 10 (IQR, 6–16) patients (17%) had catheter accesses. The mean bloodstream infection rate per 100 patient-months was 0.52±1.1 for patients with all vascular accesses, 2.15±6.5 for patients with catheters, and 0.23±0.8 for patients without catheters (Table 1). The relative risk of a bloodstream infection in patients with a catheter compared with patients without a catheter was 7.5 (95% CI, 6.3 to 8.9; P<0.001). Comparing year 2016 and 2015, the relative risk for bloodstream infections was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.86 to 1.12).

Table 1.

Average monthly bloodstream infection rates observed for 179 hemodialysis facilities in New England in 2015–2016

| All Hemodialysis Facilities and Facility Subgroupsa | No. of Monthly Observations | Mean Bloodstream Infection Rate for Patients with Any Access | Mean Bloodstream Infection Rate for Patients with Catheters | Mean Bloodstream Infection Rate for Patients without Catheters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All facilities | 4203 | 0.52±1.1 | 2.15±6.5 | 0.23±0.8 |

| Batch-submitting organizationb | ||||

| Provider 1 | 0.53±1.9 | 2.20±5.8 | 0.28±0.8 | |

| Provider 2 | 0.56±1.1 | 2.68±8.0 | 0.24±0.7 | |

| Provider 3 | 0.42±0.9 | 1.38±4.2 | 0.22±0.7 | |

| Provider 4 | 0.68±1.5 | 2.30±7.2 | 0.20±1.0 | |

| Provider 5 | 0.59±1.2 | 3.04±7.9 | 0.26±1.1 | |

| Hospital-based outpatient facilities | 132 | 0.94±2.0 | 3.84±8.9 | 0.49±2.1 |

| Nonhospital-based facilities | 4071 | 0.50±1.0 | 2.10±6.4 | 0.22±0.7 |

| Percentage of patients with catheters per facility | ||||

| <10% | 578 | 0.54±1.1 | 4.37±12.9 | 0.28±0.7 |

| 10%–14.9% | 1042 | 0.47±0.9 | 2.17±5.6 | 0.23±0.7 |

| 15%–19.9% | 1108 | 0.50±1.0 | 1.93±5.0 | 0.21±0.7 |

| ≥20% | 1475 | 0.55±1.2 | 1.47±3.7 | 0.23±1.0 |

| Total no. of patients per facility | ||||

| <25 | 460 | 0.57±1.9 | 2.71±12.4 | 0.20±1.5 |

| 25–49 | 909 | 0.54±1.2 | 1.94±5.8 | 0.22±0.9 |

| 50–99 | 1980 | 0.48±0.9 | 1.96±5.1 | 0.23±0.7 |

| ≥100 | 854 | 0.54±0.7 | 2.55±5.5 | 0.26±0.5 |

| Season of the year | ||||

| Spring | 1049 | 0.50±1.1 | 1.99±5.6 | 0.23±1.0 |

| Summer | 1056 | 0.54±1.1 | 2.16±5.7 | 0.24±0.8 |

| Fall | 1056 | 0.50±1.1 | 2.33±7.7 | 0.20±0.8 |

| Winter | 1042 | 0.52±1.0 | 2.14±6.7 | 0.25±0.7 |

Bloodstream infection rates are shown unadjusted per 100 patient-months (±SD) for all facilities and the facility subgroups analyzed for patients with any vascular access, patients with catheter accesses, and patients without catheters.

For the three large dialysis organizations and the two independently owned facilities, we have randomized their order and omitted the number of monthly observations to preserve confidentiality of the provider organizations. Among these groups of providers, the number of observations ranged from 216 to 1728.

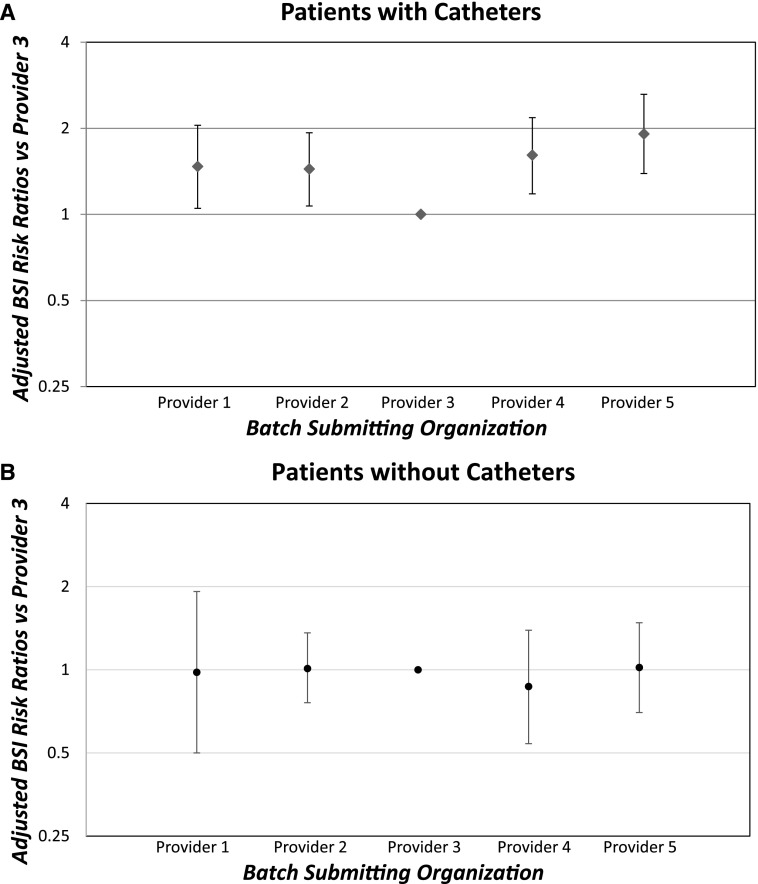

Analyses of Patients with and without Catheters, by Provider Organizations

The unadjusted mean bloodstream infection rates in the subset of patients with and without catheters are shown in Table 1. Multivariable regression analysis (Table 2) showed that for bloodstream infection rates in patients with catheters, four of the dialysis provider organizations had 1.44 (95% CI, 1.07 to 1.93) to 1.91 (95% CI, 1.39 to 2.63) times the bloodstream infection rate of provider 3 (P<0.001; Figure 1A). The mean bloodstream infection rates for patients without a catheter were not different among the five provider batch-submitting organizations (Figure 1B), but two provider groups had significantly higher bloodstream infection rates than provider 3 in all patients because of the high bloodstream infection rates in their patients with catheters. In the 11 hospital-based outpatient facilities, the mean bloodstream infection rates of patients with catheters (3.84±8.9 per 100 patient-months) and the adjusted bloodstream infection risk ratios (1.23; 95% CI, 0.74 to 2.02) were insignificantly higher than nonhospital-based facilities. However, removing the hospital facilities did not change the significance of the bloodstream infection risk ratios between the provider organizations (Table 2 footnote a).

Table 2.

Risk ratio results of multivariable regression models of bloodstream infection rates in New England hemodialysis facilities throughout 2015 and 2016

| Patients with any access | Patients with Catheters | Patients without Catheters | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemodialysis Facility Subgroupsa,b | No. of BSIs | Patient-Months | Risk Ratiosa (95% CI) | No. of BSIs | Patient-Months | Risk Ratiosa (95% CI) | No. of BSIs | Patient-Months | Risk Ratiosa (95% CI) |

| Batch-submitting organizationc | P=0.02 | P≤0.001 | P=0.98 | ||||||

| Provider 1 | 1.23 (0.87 to 1.73) | 1.47 (1.05 to 2.05) | 0.98 (0.50 to 1.92) | ||||||

| Provider 2 | 1.23 (0.97 to 1.56) | 1.44 (1.07 to 1.93) | 1.01 (0.76 to 1.36) | ||||||

| Provider 3 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | ||||||

| Provider 4 | 1.41 (1.08 to 1.86) | 1.61 (1.18 to 2.18) | 0.87 (0.54 to 1.39) | ||||||

| Provider 5 | 1.52 (1.15 to 2.02) | 1.91 (1.39 to 2.63) | 1.02 (0.70 to 1.48) | ||||||

| Hospital-based versus nonhospital-based facilities | P=0.28 | P=0.42 | P=0.10 | ||||||

| Hospital-based | 68 | 7647 | 1.21 (0.86 to 1.71) | 44 | 1427 | 1.23 (0.74 to 2.05) | 24 | 6220 | 1.46 (0.93 to 2.29) |

| Nonhospital-based | 1448 | 290,390 | 1.00 (Referent) | 881 | 48,640 | 1.00 (Referent) | 567 | 241,750 | 1.00 (Referent) |

| Percentage of patients with catheter per facility | P=0.68 | P≤0.001 | P=0.30 | ||||||

| <10% | 275 | 47,552 | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.18) | 139 | 3597 | 2.03 (1.42 to 2.91) | 136 | 43,955 | 1.27 (0.90 to 1.77) |

| 10%–14.9% | 357 | 77,992 | 0.93 (0.79 to 1.10) | 195 | 9759 | 1.41 (1.14 to 1.75) | 162 | 68,233 | 1.13 (0.86 to 1.46) |

| 15%–19.9% | 400 | 81,288 | 1.02 (0.87 to 1.19) | 261 | 14,131 | 1.36 (1.13 to 1.63) | 139 | 67,157 | 0.97 (0.74 to 1.28) |

| ≥20% | 484 | 91,205 | 1.00 (Referent) | 330 | 22,580 | 1.00 (Referent) | 154 | 68,625 | 1.00 (Referent) |

| Total no. of patients per facility | P=0.20 | P=0.24 | P=0.48 | ||||||

| <25 | 43 | 7305 | 1.02 (0.71 to 1.47) | 33 | 1676 | 1.00 (0.64 to 1.56) | 10 | 5629 | 0.70 (0.35 to 1.41) |

| 25–49 | 186 | 35,373 | 0.87 (0.68 to 1.13) | 125 | 6681 | 0.93 (0.67 to 1.28) | 61 | 28,692 | 0.79 (0.55 to 1.14) |

| 50–99 | 685 | 145,005 | 0.82 (0.67 to 1.00) | 410 | 24,329 | 0.79 (0.60 to 1.03) | 275 | 120,676 | 0.87 (0.68 to 1.11) |

| ≥100 | 602 | 110,354 | 1.00 (Referent) | 357 | 17,381 | 1.00 (Referent) | 245 | 92,973 | 1.00 (Referent) |

| Season of the year | P=0.50 | P=0.77 | P=0.36 | ||||||

| Spring | 359 | 74,329 | 0.92 (0.80 to 1.07) | 222 | 12,648 | 0.96 (0.79 to 1.17) | 137 | 61,681 | 0.85 (0.69 to 1.05) |

| Summer | 401 | 75,242 | 1.02 (0.88 to 1.17) | 244 | 12,337 | 1.07 (0.88 to 1.29) | 157 | 62,905 | 0.95 (0.77 to 1.16) |

| Fall | 373 | 75,466 | 0.94 (0.81 to 1.10) | 233 | 12,497 | 1.01 (0.83 to 1.23) | 140 | 62,969 | 0.84 (0.67 to 1.06) |

| Winter | 383 | 73,000 | 1.00 (Referent) | 226 | 12,585 | 1.00 (Referent) | 157 | 60,415 | 1.00 (Referent) |

BSI, bloodstream infection; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Each column represents a separate log-binomial regression model that was fit using generalized estimating equation methods. Each model was adjusted for the following variables: facility catheter percentage, patients per facility, batch-submitting organizations, hospital- or nonhospital-based outpatient facility, and season of the year. When the model is calculated with the hospital-based outpatient facilities removed, the results are essentially the same, with only small changes in the second decimal place (P remains <0.001).

Number of BSIs, total patient-months, and adjusted risk ratio comparisons are shown for hemodialysis facility subgroups for all patients with any vascular access, patients with catheters, and patients without catheters.

For the three large dialysis organizations and the two independently owned facilities, we have maintained the same randomized order as Table 1 and omitted the number of bloodstream infections and patient-months to preserve confidentiality of the provider organizations. Among these groups of providers, the number of bloodstream infections ranged from 71 to 508 overall and from 43 to 287 in the patients with catheters.

Figure 1.

Adjusted risk ratios and 95% CIs of bloodstream infection (BSI) rates in 2015-2016 showing increased BSI risk in four of five batch submitting hemodialysis provider organizations for patients with catheters but not for patients without catheters. (A) patients with catheters and (B) patients without catheters. Results are on the basis of multivariable regression models (Table 2 footnote a) with Provider 3 group as referent.

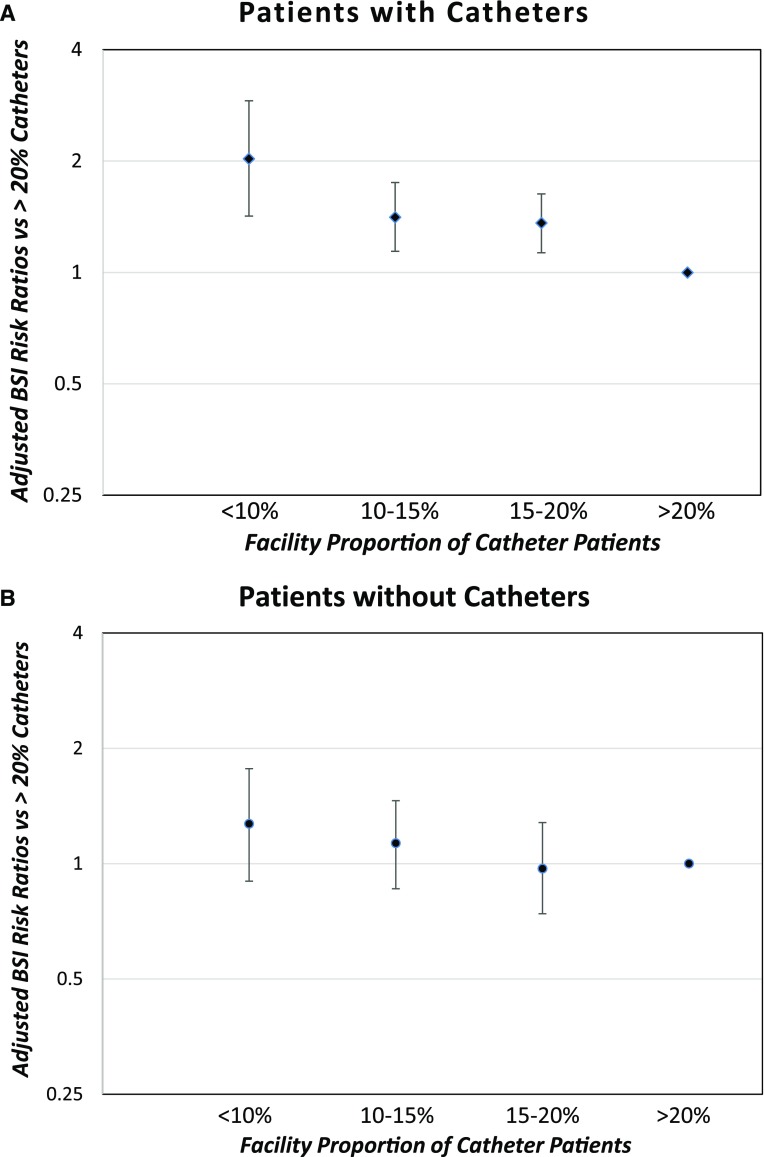

Analyses by Facility Proportions of Patients with Catheters, Census, and Season

The mean bloodstream infection rates for patients with catheters are significantly and progressively higher in facilities with lower proportions of this patient group. The facilities with <20% catheter patients have higher bloodstream infection rates in this patient group than facilities with >20% catheter patients, and facilities with <10% catheters have adjusted risk ratios for bloodstream infections in their patients with catheters that are 2.0 times those of facilities with >20% catheters (P≤0.001; Figure 2A). In contrast, the mean bloodstream infection rates were not different for patients with all vascular accesses or noncatheter accesses (Figure 2B), on the basis of the percentages of patients with catheters in facilities. Likewise, the bloodstream infection rates were similar for facilities with fewer or more total patients, and were unchanged across seasons of the year.

Figure 2.

Adjusted risk ratios and 95% CIs of bloodstream infection (BSI) rates on the basis of facility proportions of catheters in 2015-2016 showing increasing BSI risk with lower proportions of catheters in the patients with catheters but not the patients without catheters. (A) patients with catheters and (B) patients without catheters. Results are on the basis of multivariable regression models (Table 2 footnote a) with >20% catheter patient population as referent.

Because a lower proportion of patients with catheters, with their concomitant higher bloodstream infection rates, might pose a selection bias to explain the higher bloodstream infection rates in this patient group, we assessed the mean percentage of patients with a catheter in the five provider batch-submitting organizations and the hospital-based outpatient facilities (Table 3). Although there is a significant difference between provider organizations, on the basis of the multivariable analysis of the risk ratios adjusted for the facility proportion of catheters, a lower percentage of patients with catheters among the dialysis provider organizations and the hospital-based facilities compared with provider 3 would not offer an explanation for the comparatively higher bloodstream infection rates in this patient group.

Table 3.

The average proportion of patients with catheters per facility for each of the five batch-submitting organizations and the 11 hospital-based outpatient facilities

| Facilities by Provider Batch-Submitting Organizationa | Mean Percentage of Patients with Catheters per Facility (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|

| P<0.001 | |

| Provider 1 | 15.8 (12.5 to 19.1) |

| Provider 2 | 15.1 (13.8 to 16.3) |

| Provider 3 | 18.6 (17.5 to 19.7) |

| Provider 4 | 23.2 (20.4 to 25.9) |

| Provider 5 | 17.2 (14.1 to 20.3) |

| Hospital-based | 22.8 (17.4 to 28.2) |

The five batch-submitting organizations remain in the same randomized order as Tables 1 and 2. The 11 hospital-based outpatient facilities are listed separately from the other provider groups, which show only the percentage of patients with catheters in their nonhospital-based facilities. Despite the significant differences between provider organizations, the percentages of patients with catheters did not account for the differences in bloodstream infection rates in this patient group between the provider groups.

Discussion

We undertook an observational study of all Medicare facilities that provided outpatient hemodialysis in New England throughout 2015 and 2016 to assess the associations of bloodstream infection rates in patients receiving hemodialysis with catheter or permanent vascular accesses in each facility. As expected, patients with catheters had much higher bloodstream infection rates than patients without catheters, with a relative risk of a bloodstream infection in patients with versus without catheters of 7.5 (95% CI, 6.3 to 8.9). The mean bloodstream infection rate in patients with catheters in New England of 2.15 in 2015–2016 was no better than the 2.14 per 100 patient-months reported by the CDC for the United States in 2014 (4), likely continuing the 38% increase in hospitalization admission rates reported for hemodialysis bacteremia/sepsis between 2004 and 2013 (18).

However, we found wide disparities of the bloodstream infection rates in patients with catheters among hemodialysis facilities, such that four dialysis provider organizations had adjusted risk ratios of 1.44 (95% CI, 1.07 to 1.93) to 1.91 (95% CI, 1.39 to 2.63) times the best-performing dialysis provider organization. Because the bloodstream infection rates for patients without catheters were similar among all of the provider organizations, these findings may suggest differences in the infection control techniques for patients with catheters among the facilities of the various provider organizations. Catheter care at initiation and completion of hemodialysis is largely performed by patient care technicians, rather than nurses, in outpatient hemodialysis facilities in the United States. Without prior professional knowledge, the training of these patient care technicians is performed by the dialysis facility or provider organization that hires them. Our finding of significantly higher bloodstream infection rates of patients with catheters among hemodialysis facilities of certain provider organizations is concerning. The training programs for newly hired dialysis technicians and nurses are, in general, more formalized, with 6 weeks of classroom training, and extensive, lasting 12 weeks overall, in some dialysis provider organizations rather than the variability of learning largely by apprenticeship that takes place in other dialysis provider facilities. In two recent editorials (10,19), Dr. Kliger requests that the kidney community target zero preventable infections with the “Nephrologists Transforming Dialysis Safety” effort; our data support this need for better infection control techniques for catheter care in many hemodialysis facilities.

One surprising finding was that bloodstream infection rates in patients with catheters were negatively correlated with the proportion of this patient group in the hemodialysis facilities. When comparing subsets of facilities having increasing proportions of patients with catheters, we found that, in facilities with <10% catheter patients, these patients had high bloodstream infection rates of 4.4 per 100 patient-months, falling progressively to as low as 1.5 per 100 patient-months in facilities with >20% catheter patients, for an adjusted relative risk of 2.0 (P≤0.001; Figure 2A). No such relationship was found between the overall bloodstream infection rates or the bloodstream infection rates of patients without catheters and the percentage of patients with catheters. Although an observational study can only speculate on the cause of this striking difference, we suspect two explanations may be inferred from our data.

First, it has been previously shown that there are selection factors among patients with catheters that contribute to the majority, or over two thirds, of the significantly higher mortality rates of patients with catheters over patients with arteriovenous fistulas (20,21). More recently, data have shown that patients receiving hemodialysis who undergo fistula placement had lower bloodstream infection hospitalization rates than those who undergo graft placement despite greater catheter dependence (22), a reason to suspect selection factors among subsets of patients with catheters that may predispose them to greater or lesser risks of infection. This leads us to speculate that there may be a “dilution” of patients with catheters in facilities with high catheter percentages, with greater numbers of patients selected for permanent accesses at other facilities, who are therefore at lower risk of both bloodstream infections and mortality. For instance, patients with catheters in facilities with low catheter percentages may be mainly higher risk patients that are considered to be less suitable for permanent accesses, whereas those in facilities with >20% catheters may include “healthier” patients that would not have a catheter in the <10% catheter facilities. Of course, this speculation makes the unwarranted assumption that we can exclude the effect of the catheter to increase bloodstream infections in these presumptive lower risk patients. Moreover, even if this dilution effect theory is true, by projecting the bloodstream infection rates of patients without catheters to those with catheters, we could mathematically explain only a portion of the markedly lower mean bloodstream infection rate of 1.47 per 100 patient-months in facilities with >20% catheter percentages. In addition, although patient selection factors likely play a major role in explaining the large differences in bloodstream infection rates among hemodialysis facilities, particularly for the hospital-based outpatient facilities, differences in the proportion of patients with catheters in the facilities of the various provider organizations fails to account for their differences in bloodstream infection rates in this patient group.

Second, as noted above, the wide disparities in bloodstream infection rates among hemodialysis provider organizations raise concern that infection control techniques may be better in facilities with greater numbers of patients with catheters. At the very least, the experience all staff receive in treating patients with catheters is more frequent in facilities caring for higher proportions of this patient group.

Whatever the actual explanations for this large disparity are, we propose that bloodstream infection rates in patients with catheters may serve as a better quality-of-care parameter of facilities than their overall bloodstream infection rates and be of similar importance as their percentage of patients with catheters. Bloodstream infection rates in patients with catheters are likely to reflect aspects of the facility’s quality of infection control directly whereas the proportion of catheters are only marginally under the facility staff’s control (i.e., they are on the basis of patient referrals, vascular access surgeons available, affiliated nephrology practices, etc.). The importance of bloodstream infection monitoring has been stressed to create quality improvement programs for better patient care and outcomes (5,23). We endorse the risk-adjusted bloodstream infection rates added to the 2018 CMS ESKD QIP (24,25), but suggest that the QIP would be better limited to bloodstream infection rates in only patients with catheters rather than overall bloodstream infection rates. The overall bloodstream infection rates include patient selection factors, such as diabetes or peripheral vascular disease, that are not under facility control and difficult to adjust for “risk” rather than the quality of the hemodialysis facility’s catheter care techniques.

Additionally, we found no effect of either facility size on the basis of patient census or season of the year on bloodstream infection rates. The lack of a seasonal influence conflicts with that of a Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study study showing higher catheter-related infection and septicemia rates in the summer (26). This difference may represent a change in catheter care between the time period of their study from 1996 to 2009 and ours from 2015 to 2016, or perhaps, the variation of our seasonal dates (calendar-defined with January 1 as the start of winter) from theirs (solstice-defined, with December 22 as the start of winter).

The limitations of our findings are it is a retrospective observational study subject to over- or underreporting and selection bias, in which case mix adjustment is not possible. The data depend upon the accuracy of reporting to CROWNWeb and NHSN, which we think was quite accurate by 2016. The IPRO ESRD Network of New England sends out requests monthly to all facilities with missing data, helping to ensure completeness. Moreover, our large sample of all New England adult hemodialysis facilities operating throughout 2015–2016, with >4000 monthly observations in >12,000 patients each month, allowed for robust statistical comparisons. In our unselected study population, the bloodstream infection rate is unbiased by selected study populations (26) and for this reason may be considerably higher than in clinical studies (3). There were small numbers of nontunneled catheters included among the patients with catheters, a group found to be at somewhat higher risk for bloodstream infections by some (11,27), but not all reports (28). Only six bloodstream infections were reported in patients with nontunneled catheters throughout 2015–2016, not affecting the bloodstream infection rates of patients with catheters. There are other limitations that might be cited. The bloodstream infection rates were not reported separately for patients with catheters less than or more than 90 days, and the number of patients in each facility is only on the basis of the first two dialysis days of the month, as reported in CROWNWeb. Of course, there may be considerable heterogeneity among the facilities in the provider organizations with high bloodstream infection rates that cannot be assessed from cumulative data. Further, perhaps our findings may not be applicable to facilities outside of New England, but studying the patients of this somewhat more homogeneous region should allow for better comparisons among the different hemodialysis facilities.

In summary, we found that four dialysis provider organizations have significantly higher bloodstream infection rates in patients with catheters than one of the dialysis provider organizations. Furthermore, an unrecognized counterintuitive finding is that hemodialysis facilities with lower proportions of patients with catheters have markedly higher bloodstream infection rates in this patient group than those with higher proportions of catheters. However, that finding did not explain the differences of bloodstream infection rates between the dialysis provider organizations. These data point to a need for better infection control training and experience of the staff in facilities with low proportions of patients with catheters and facilities operated by some dialysis providers. Also, because facilities with low proportions of catheters were presumed to provide higher quality of care without specific evidence of this, the bloodstream infection rate in patients with catheters may be a better parameter of the actual quality of care than the percentage of patients with catheters.

Disclosures

R.S.B. is Associate Medical Director for DaVita Brookline Dialysis Center, and K.B. was an employee of IPRO ESRD Network of New England at the time of the study, and is now employed by DaVita HealthCare Partners, Inc., but neither author has any direct conflict with this research. R.B.D. has no conflicts.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the input provided by the IPRO ESRD Network of New England.

This work was conducted with partial support from the Harvard Catalyst (National Institutes of Health award UL1 TR001102).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Allon M: Current management of vascular access. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 786–800, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lok CE, Mokrzycki MH: Prevention and management of catheter-related infection in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 79: 587–598, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravani P, Palmer SC, Oliver MJ, Quinn RR, MacRae JM, Tai DJ, Pannu NI, Thomas C, Hemmelgarn BR, Craig JC, Manns B, Tonelli M, Strippoli GFM, James MT: Associations between hemodialysis access type and clinical outcomes: A systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 465–473, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(CDC) NHSN: Bloodstream Infection (BSI) Rate Stratified by Vascular Access Type—NHSN Dialysis Event Data, 2014. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/dialysis/bsi-rate-vat-de-2014.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2017

- 5.Nguyen DB, Shugart A, Lines C, Shah AB, Edwards J, Pollock D, Sievert D, Patel PR: National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) dialysis event surveillance report for 2014. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1139–1146, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel PR, Yi SH, Booth S, Bren V, Downham G, Hess S, Kelley K, Lincoln M, Morrissette K, Lindberg C, Jernigan JA, Kallen AJ: Bloodstream infection rates in outpatient hemodialysis facilities participating in a collaborative prevention effort: A quality improvement report. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 322–330, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yi SH, Kallen AJ, Hess S, Bren VR, Lincoln ME, Downham G, Kelley K, Booth SL, Weirich H, Shugart A, Lines C, Melville A, Jernigan JA, Kleinbaum DG, Patel PR: Sustained infection reduction in outpatient hemodialysis centers participating in a collaborative bloodstream infection prevention effort. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 37: 863–866, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunelli SM, Van Wyck DB, Njord L, Ziebol RJ, Lynch LE, Killion DP: Cluster-randomized trial of devices to prevent catheter-related bloodstream infection. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 1336–1343, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrick R, Kliger A, Stefanchik B: Patient and facility safety in hemodialysis: Opportunities and strategies to develop a culture of safety. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 680–688, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kliger AS: Targeting zero infections in dialysis: New devices, yes, but also guidelines, checklists, and a culture of safety. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 1083–1084, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pastan S, Soucie JM, McClellan WM: Vascular access and increased risk of death among hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 62: 620–626, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeSilva RN, Patibandla BK, Vin Y, Narra A, Chawla V, Brown RS, Goldfarb-Rumyantzev AS: Fistula first is not always the best strategy for the elderly. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1297–1304, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravani P, Quinn R, Oliver M, Robinson B, Pisoni R, Pannu N, MacRae J, Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, James M, Tonelli M, Gillespie B: Examining the association between hemodialysis access type and mortality: The role of access complications. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 955–964, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: ESRD Quality Incentive Program. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/. Accessed December 4, 2017

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: 2016 Dialysis Facility Compare Star Ratings Refresh. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/End-Stage-Renal-Disease/ESRDGeneralInformation/Downloads/2016-Dialysis-Facility-Compare-Star-Ratings-Refresh.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2017

- 16.Patel PR, Brinsley-Rainisch K: The making dialysis safer for patients coalition: A new partnership to prevent hemodialysis-related infections. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 175–181, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Dialysis Event Surveillance Protocol. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/8pscdialysiseventcurrent.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2018

- 18.Wetmore JB, Li S, Molony JT, Guo H, Herzog CA, Gilbertson DT, Peng Y, Collins AJ: Insights from the 2016 peer kidney care initiative report: Still a ways to go to improve care for dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 123–132, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kliger AS, Collins AJ: Long overdue need to reduce infections with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1728–1729, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown RS, Patibandla BK, Goldfarb-Rumyantzev AS: The survival benefit of “Fistula First, Catheter Last” in hemodialysis is primarily due to patient factors. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 645–652, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quinn RR, Oliver MJ, Devoe D, Poinen K, Kabani R, Kamar F, Mysore P, Lewin AM, Hiremath S, MacRae J, James MT, Miller L, Hemmelgarn BR, Moist LM, Garg AX, Chowdhury TT, Ravani P: The effect of predialysis fistula attempt on risk of all-cause and access-related death. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 613–620, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee T, Thamer M, Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Allon M: Vascular access type and clinical outcomes among elderly patients on hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1823–1830, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miskulin DC, Gul A: Infection monitoring in dialysis units: A plea for “Cleaner” data. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1038–1039, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: ESRD QIP Summary: Payment Years 2016 – 2020. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/Downloads/ESRD-QIP-Summary-Payment-Years-2016-%E2%80%93-2020.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2017

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Quality Forum: #1460 Bloodstream Infection in Hemodialysis Outpatients, Last Measure Information, 2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/nqf/nqf-dialysis-bsi-measureinfo.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2017

- 26.Lok CE, Thumma JR, McCullough KP, Gillespie BW, Fluck RJ, Marshall MR, Kawanishi H, Robinson BM, Pisoni RL: Catheter-related infection and septicemia: Impact of seasonality and modifiable practices from the DOPPS. Semin Dial 27: 72–77, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weijmer MC, Vervloet MG, ter Wee PM: Compared to tunnelled cuffed haemodialysis catheters, temporary untunnelled catheters are associated with more complications already within 2 weeks of use. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 670–677, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomson PC, Stirling CM, Geddes CC, Morris ST, Mactier RA: Vascular access in haemodialysis patients: A modifiable risk factor for bacteraemia and death. QJM 100: 415–422, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]